User login

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

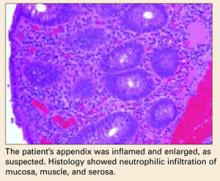

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.