User login

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

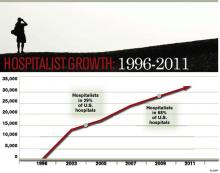

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

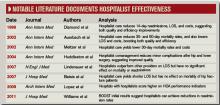

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.