User login

At North Shore Medical Center in Salem, Mass., interest in reducing elective deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation started with a newborn with respiratory problems.

A few years ago, when a patient was induced at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the newborn ended up having significant respiratory complications and had to be transferred to a tertiary care center, said Dr. Allyson L. Preston, chair of obstetrics and gynecology there.

Although the baby recovered and did fine, a review of the case led to a deeper examination of the data on elective deliveries at 37-39 weeks. The result was a growing realization that early elective deliveries weren’t as benign as previously thought, Dr. Preston said in an interview.

After hearing about the success that Intermountain Healthcare in Utah had in reducing early elective deliveries, Dr. Preston worked with her physician and nursing colleagues in the department of ob.gyn. to develop a policy not to schedule either elective inductions or cesarean sections if the patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there was a medical or obstetrical indication that early delivery was necessary.

In early 2010, the hospital staff sent out new booking forms to area obstetrical offices. The new forms required physicians to note the indications for early delivery and the gestational age. The charge nurses at North Shore Medical Center were given the authority not to schedule procedures if a patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation and the physician did not include an accepted medical or obstetrical indication for delivery. Physicians who took exception to the policy were referred to Dr. Preston. For the most part, physicians have eagerly adopted the policy, she said.

"I think people realized we were serious about it," Dr. Preston said. "They realized it was the right thing to do."

The results since the policy was implemented have been fairly dramatic. Data released earlier this year by the Leapfrog Group show that in 2010, the early elective newborn delivery rate was 31.6% at North Shore, compared with just 1.6% in 2011. That means that among deliveries done at 37-39 weeks, more than 98% are now medically indicated, according to Dr. Preston.

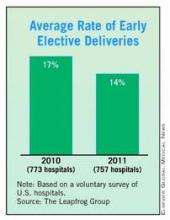

Other hospitals around the country are experiencing similar success, according to data from the Leapfrog Group’s annual hospital survey. The survey of 757 hospitals found that 39% of reporting hospitals had early elective delivery rates of 5% or less in 2011, compared with 30% the previous year. The rate of elective deliveries represents the percentage of nonmedically indicated births at 37-39 weeks’ gestation delivered by caesarean section or induction. The average rate for early elective deliveries among these hospitals dropped from 17% to 14% between 2010 and 2011.

Despite the progress already being made to curb early deliveries in some hospitals, there was still a wide variation among the hospitals in the Leapfrog survey, with early elective delivery rates ranging from a low of less than 5% to more than 40%, according to the 2011 data.

The Leapfrog Group (a coalition of public and private purchasers of employee health benefits that works on health care quality improvement) began collecting data on early elective deliveries in 2009 and first publicly reported hospital data in 2010. The group has identified the trend toward early deliveries as both a safety and an economic issue. For instance, women who are induced in weeks 37 and 38 have a higher risk of needing a cesarean section than do women who go into labor on their own. Studies also have linked early elective deliveries to postpartum complications such as hematoma, wound dehiscence, anemia, endometriosis, urinary tract infections, and sepsis, according to the Leapfrog Group.

The Leapfrog Group is not the only organization that has made the reduction of early elective deliveries a priority. For many years, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended against elective deliveries before 39 weeks. In February, the federal government added its weight to the push to reduce these types of elective deliveries with the launch of its Strong Start initiative. Under the new effort, officials at the Department of Health and Human Services will work with outside partners to test a nationwide awareness campaign on best practices to reduce the rate of early elective deliveries before 39 weeks among all pregnant women. They will also test "enhanced prenatal care" approaches for Medicaid beneficiaries who are at risk for preterm birth.

The latest Leapfrog data are consistent with what other efforts that are aimed at reducing early elective deliveries have been able to show, said Dr. Donald Dudley, professor and vice chair for research in the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio.

Dr. Dudley also has been active in the March of Dimes Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative, which has been working to reduce preterm births through evidence-based quality improvement projects.

The Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative worked with 25 hospitals in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas to implement a policy of not performing elective deliveries before 39 weeks unless they are medically indicated. They found that hospitals – regardless of their size or location – were able to rapidly reduce early elective deliveries. The key, Dr. Dudley said, was making physicians and nurses aware of the data on complications from early deliveries.

Dr. Dudley said some physicians are skeptical that those last few weeks make that big a difference. He had been one of them. But once he read through the studies, it became clear that deliveries before 39 weeks were not the safest path for mothers and babies. "You’ll come away saying it is really not a good idea to do elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks," he said.

Once the buy-in from providers is there, making the change is fairly simple and relatively cheap, Dr. Dudley said. Hospitals can take advantage of free toolkits like the one from the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative and the March of Dimes.

The most costly and time-intensive part of any effort to reduce early elective deliveries is the data collection, he said. Hospitals need to know how they doing at the start, but many community hospitals don’t routinely collect those data.

Dr. Dudley cautioned hospitals to be careful not to push the policy so hard that they discourage physicians from exercising their clinical judgment. "One of the things we have to be really careful about is not to swing the pendulum so far the other way that we disengage our brains."

If there’s a reason for a patient to be delivered at less than 39 weeks, then the delivery is indicated, not elective, he said. And there is a long list of appropriate indications for an early delivery.

For example, Dr. Dudley said he recently had a patient whom he had been monitoring and hoping to deliver after 39 weeks, but at 38 and a half weeks her blood pressure began creeping up enough that it was necessary to do the delivery early. The patient had a history of hypertension, and the risk of waiting outweighed the risks of early induction, he said. "You don’t want to delay acting when there’s an acceptable indication."

Policies aimed at reducing early elective deliveries can introduce a reluctance to induce (either by the physician or the patient) that may result in delaying an induction that is actually indicated, said Dr. William H. Barth Jr., chief of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, where the early elective newborn delivery rate has declined from 8% to 4% between 2010 and 2011. "Recommending an induction is a complex decision," he said. "The recent push to decrease elective inductions is sort of one more factor in the mix of that complex decision."

But the other issue is simple math, Dr. Barth said. If more inductions are delayed – indicated or not – there will be more stillbirths. He pointed to a retrospective cohort study published last year in Obstetrics & Gynecology that looked at the effect of a policy limiting elective delivery before 39 weeks’ gestation. The researchers found a significant decrease in admissions to the neonatal ICU, but they also detected an increase in stillbirths at 37 and 38 weeks (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1047-55).

Dr. Barth advised hospitals considering formal policies to reduce early elective deliveries to track not only the number of elective deliveries, but also stillbirths. "Shared decision making between patients and physicians is best conducted with all of the information – good and bad," he said.

At North Shore Medical Center in Salem, Mass., interest in reducing elective deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation started with a newborn with respiratory problems.

A few years ago, when a patient was induced at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the newborn ended up having significant respiratory complications and had to be transferred to a tertiary care center, said Dr. Allyson L. Preston, chair of obstetrics and gynecology there.

Although the baby recovered and did fine, a review of the case led to a deeper examination of the data on elective deliveries at 37-39 weeks. The result was a growing realization that early elective deliveries weren’t as benign as previously thought, Dr. Preston said in an interview.

After hearing about the success that Intermountain Healthcare in Utah had in reducing early elective deliveries, Dr. Preston worked with her physician and nursing colleagues in the department of ob.gyn. to develop a policy not to schedule either elective inductions or cesarean sections if the patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there was a medical or obstetrical indication that early delivery was necessary.

In early 2010, the hospital staff sent out new booking forms to area obstetrical offices. The new forms required physicians to note the indications for early delivery and the gestational age. The charge nurses at North Shore Medical Center were given the authority not to schedule procedures if a patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation and the physician did not include an accepted medical or obstetrical indication for delivery. Physicians who took exception to the policy were referred to Dr. Preston. For the most part, physicians have eagerly adopted the policy, she said.

"I think people realized we were serious about it," Dr. Preston said. "They realized it was the right thing to do."

The results since the policy was implemented have been fairly dramatic. Data released earlier this year by the Leapfrog Group show that in 2010, the early elective newborn delivery rate was 31.6% at North Shore, compared with just 1.6% in 2011. That means that among deliveries done at 37-39 weeks, more than 98% are now medically indicated, according to Dr. Preston.

Other hospitals around the country are experiencing similar success, according to data from the Leapfrog Group’s annual hospital survey. The survey of 757 hospitals found that 39% of reporting hospitals had early elective delivery rates of 5% or less in 2011, compared with 30% the previous year. The rate of elective deliveries represents the percentage of nonmedically indicated births at 37-39 weeks’ gestation delivered by caesarean section or induction. The average rate for early elective deliveries among these hospitals dropped from 17% to 14% between 2010 and 2011.

Despite the progress already being made to curb early deliveries in some hospitals, there was still a wide variation among the hospitals in the Leapfrog survey, with early elective delivery rates ranging from a low of less than 5% to more than 40%, according to the 2011 data.

The Leapfrog Group (a coalition of public and private purchasers of employee health benefits that works on health care quality improvement) began collecting data on early elective deliveries in 2009 and first publicly reported hospital data in 2010. The group has identified the trend toward early deliveries as both a safety and an economic issue. For instance, women who are induced in weeks 37 and 38 have a higher risk of needing a cesarean section than do women who go into labor on their own. Studies also have linked early elective deliveries to postpartum complications such as hematoma, wound dehiscence, anemia, endometriosis, urinary tract infections, and sepsis, according to the Leapfrog Group.

The Leapfrog Group is not the only organization that has made the reduction of early elective deliveries a priority. For many years, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended against elective deliveries before 39 weeks. In February, the federal government added its weight to the push to reduce these types of elective deliveries with the launch of its Strong Start initiative. Under the new effort, officials at the Department of Health and Human Services will work with outside partners to test a nationwide awareness campaign on best practices to reduce the rate of early elective deliveries before 39 weeks among all pregnant women. They will also test "enhanced prenatal care" approaches for Medicaid beneficiaries who are at risk for preterm birth.

The latest Leapfrog data are consistent with what other efforts that are aimed at reducing early elective deliveries have been able to show, said Dr. Donald Dudley, professor and vice chair for research in the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio.

Dr. Dudley also has been active in the March of Dimes Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative, which has been working to reduce preterm births through evidence-based quality improvement projects.

The Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative worked with 25 hospitals in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas to implement a policy of not performing elective deliveries before 39 weeks unless they are medically indicated. They found that hospitals – regardless of their size or location – were able to rapidly reduce early elective deliveries. The key, Dr. Dudley said, was making physicians and nurses aware of the data on complications from early deliveries.

Dr. Dudley said some physicians are skeptical that those last few weeks make that big a difference. He had been one of them. But once he read through the studies, it became clear that deliveries before 39 weeks were not the safest path for mothers and babies. "You’ll come away saying it is really not a good idea to do elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks," he said.

Once the buy-in from providers is there, making the change is fairly simple and relatively cheap, Dr. Dudley said. Hospitals can take advantage of free toolkits like the one from the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative and the March of Dimes.

The most costly and time-intensive part of any effort to reduce early elective deliveries is the data collection, he said. Hospitals need to know how they doing at the start, but many community hospitals don’t routinely collect those data.

Dr. Dudley cautioned hospitals to be careful not to push the policy so hard that they discourage physicians from exercising their clinical judgment. "One of the things we have to be really careful about is not to swing the pendulum so far the other way that we disengage our brains."

If there’s a reason for a patient to be delivered at less than 39 weeks, then the delivery is indicated, not elective, he said. And there is a long list of appropriate indications for an early delivery.

For example, Dr. Dudley said he recently had a patient whom he had been monitoring and hoping to deliver after 39 weeks, but at 38 and a half weeks her blood pressure began creeping up enough that it was necessary to do the delivery early. The patient had a history of hypertension, and the risk of waiting outweighed the risks of early induction, he said. "You don’t want to delay acting when there’s an acceptable indication."

Policies aimed at reducing early elective deliveries can introduce a reluctance to induce (either by the physician or the patient) that may result in delaying an induction that is actually indicated, said Dr. William H. Barth Jr., chief of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, where the early elective newborn delivery rate has declined from 8% to 4% between 2010 and 2011. "Recommending an induction is a complex decision," he said. "The recent push to decrease elective inductions is sort of one more factor in the mix of that complex decision."

But the other issue is simple math, Dr. Barth said. If more inductions are delayed – indicated or not – there will be more stillbirths. He pointed to a retrospective cohort study published last year in Obstetrics & Gynecology that looked at the effect of a policy limiting elective delivery before 39 weeks’ gestation. The researchers found a significant decrease in admissions to the neonatal ICU, but they also detected an increase in stillbirths at 37 and 38 weeks (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1047-55).

Dr. Barth advised hospitals considering formal policies to reduce early elective deliveries to track not only the number of elective deliveries, but also stillbirths. "Shared decision making between patients and physicians is best conducted with all of the information – good and bad," he said.

At North Shore Medical Center in Salem, Mass., interest in reducing elective deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation started with a newborn with respiratory problems.

A few years ago, when a patient was induced at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the newborn ended up having significant respiratory complications and had to be transferred to a tertiary care center, said Dr. Allyson L. Preston, chair of obstetrics and gynecology there.

Although the baby recovered and did fine, a review of the case led to a deeper examination of the data on elective deliveries at 37-39 weeks. The result was a growing realization that early elective deliveries weren’t as benign as previously thought, Dr. Preston said in an interview.

After hearing about the success that Intermountain Healthcare in Utah had in reducing early elective deliveries, Dr. Preston worked with her physician and nursing colleagues in the department of ob.gyn. to develop a policy not to schedule either elective inductions or cesarean sections if the patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there was a medical or obstetrical indication that early delivery was necessary.

In early 2010, the hospital staff sent out new booking forms to area obstetrical offices. The new forms required physicians to note the indications for early delivery and the gestational age. The charge nurses at North Shore Medical Center were given the authority not to schedule procedures if a patient was at less than 39 weeks’ gestation and the physician did not include an accepted medical or obstetrical indication for delivery. Physicians who took exception to the policy were referred to Dr. Preston. For the most part, physicians have eagerly adopted the policy, she said.

"I think people realized we were serious about it," Dr. Preston said. "They realized it was the right thing to do."

The results since the policy was implemented have been fairly dramatic. Data released earlier this year by the Leapfrog Group show that in 2010, the early elective newborn delivery rate was 31.6% at North Shore, compared with just 1.6% in 2011. That means that among deliveries done at 37-39 weeks, more than 98% are now medically indicated, according to Dr. Preston.

Other hospitals around the country are experiencing similar success, according to data from the Leapfrog Group’s annual hospital survey. The survey of 757 hospitals found that 39% of reporting hospitals had early elective delivery rates of 5% or less in 2011, compared with 30% the previous year. The rate of elective deliveries represents the percentage of nonmedically indicated births at 37-39 weeks’ gestation delivered by caesarean section or induction. The average rate for early elective deliveries among these hospitals dropped from 17% to 14% between 2010 and 2011.

Despite the progress already being made to curb early deliveries in some hospitals, there was still a wide variation among the hospitals in the Leapfrog survey, with early elective delivery rates ranging from a low of less than 5% to more than 40%, according to the 2011 data.

The Leapfrog Group (a coalition of public and private purchasers of employee health benefits that works on health care quality improvement) began collecting data on early elective deliveries in 2009 and first publicly reported hospital data in 2010. The group has identified the trend toward early deliveries as both a safety and an economic issue. For instance, women who are induced in weeks 37 and 38 have a higher risk of needing a cesarean section than do women who go into labor on their own. Studies also have linked early elective deliveries to postpartum complications such as hematoma, wound dehiscence, anemia, endometriosis, urinary tract infections, and sepsis, according to the Leapfrog Group.

The Leapfrog Group is not the only organization that has made the reduction of early elective deliveries a priority. For many years, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended against elective deliveries before 39 weeks. In February, the federal government added its weight to the push to reduce these types of elective deliveries with the launch of its Strong Start initiative. Under the new effort, officials at the Department of Health and Human Services will work with outside partners to test a nationwide awareness campaign on best practices to reduce the rate of early elective deliveries before 39 weeks among all pregnant women. They will also test "enhanced prenatal care" approaches for Medicaid beneficiaries who are at risk for preterm birth.

The latest Leapfrog data are consistent with what other efforts that are aimed at reducing early elective deliveries have been able to show, said Dr. Donald Dudley, professor and vice chair for research in the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio.

Dr. Dudley also has been active in the March of Dimes Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative, which has been working to reduce preterm births through evidence-based quality improvement projects.

The Big 5 Prematurity Collaborative worked with 25 hospitals in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas to implement a policy of not performing elective deliveries before 39 weeks unless they are medically indicated. They found that hospitals – regardless of their size or location – were able to rapidly reduce early elective deliveries. The key, Dr. Dudley said, was making physicians and nurses aware of the data on complications from early deliveries.

Dr. Dudley said some physicians are skeptical that those last few weeks make that big a difference. He had been one of them. But once he read through the studies, it became clear that deliveries before 39 weeks were not the safest path for mothers and babies. "You’ll come away saying it is really not a good idea to do elective deliveries at less than 39 weeks," he said.

Once the buy-in from providers is there, making the change is fairly simple and relatively cheap, Dr. Dudley said. Hospitals can take advantage of free toolkits like the one from the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative and the March of Dimes.

The most costly and time-intensive part of any effort to reduce early elective deliveries is the data collection, he said. Hospitals need to know how they doing at the start, but many community hospitals don’t routinely collect those data.

Dr. Dudley cautioned hospitals to be careful not to push the policy so hard that they discourage physicians from exercising their clinical judgment. "One of the things we have to be really careful about is not to swing the pendulum so far the other way that we disengage our brains."

If there’s a reason for a patient to be delivered at less than 39 weeks, then the delivery is indicated, not elective, he said. And there is a long list of appropriate indications for an early delivery.

For example, Dr. Dudley said he recently had a patient whom he had been monitoring and hoping to deliver after 39 weeks, but at 38 and a half weeks her blood pressure began creeping up enough that it was necessary to do the delivery early. The patient had a history of hypertension, and the risk of waiting outweighed the risks of early induction, he said. "You don’t want to delay acting when there’s an acceptable indication."

Policies aimed at reducing early elective deliveries can introduce a reluctance to induce (either by the physician or the patient) that may result in delaying an induction that is actually indicated, said Dr. William H. Barth Jr., chief of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, where the early elective newborn delivery rate has declined from 8% to 4% between 2010 and 2011. "Recommending an induction is a complex decision," he said. "The recent push to decrease elective inductions is sort of one more factor in the mix of that complex decision."

But the other issue is simple math, Dr. Barth said. If more inductions are delayed – indicated or not – there will be more stillbirths. He pointed to a retrospective cohort study published last year in Obstetrics & Gynecology that looked at the effect of a policy limiting elective delivery before 39 weeks’ gestation. The researchers found a significant decrease in admissions to the neonatal ICU, but they also detected an increase in stillbirths at 37 and 38 weeks (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1047-55).

Dr. Barth advised hospitals considering formal policies to reduce early elective deliveries to track not only the number of elective deliveries, but also stillbirths. "Shared decision making between patients and physicians is best conducted with all of the information – good and bad," he said.