User login

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

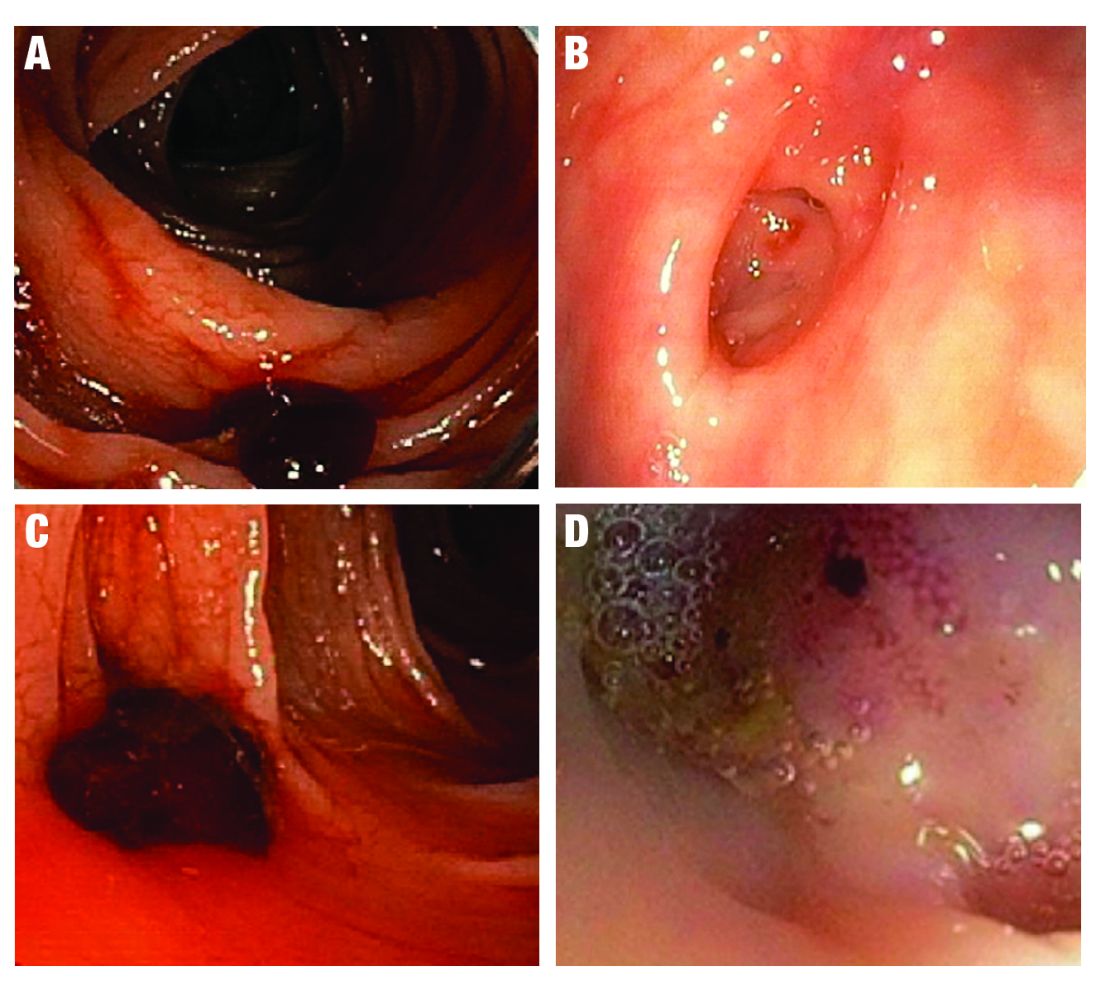

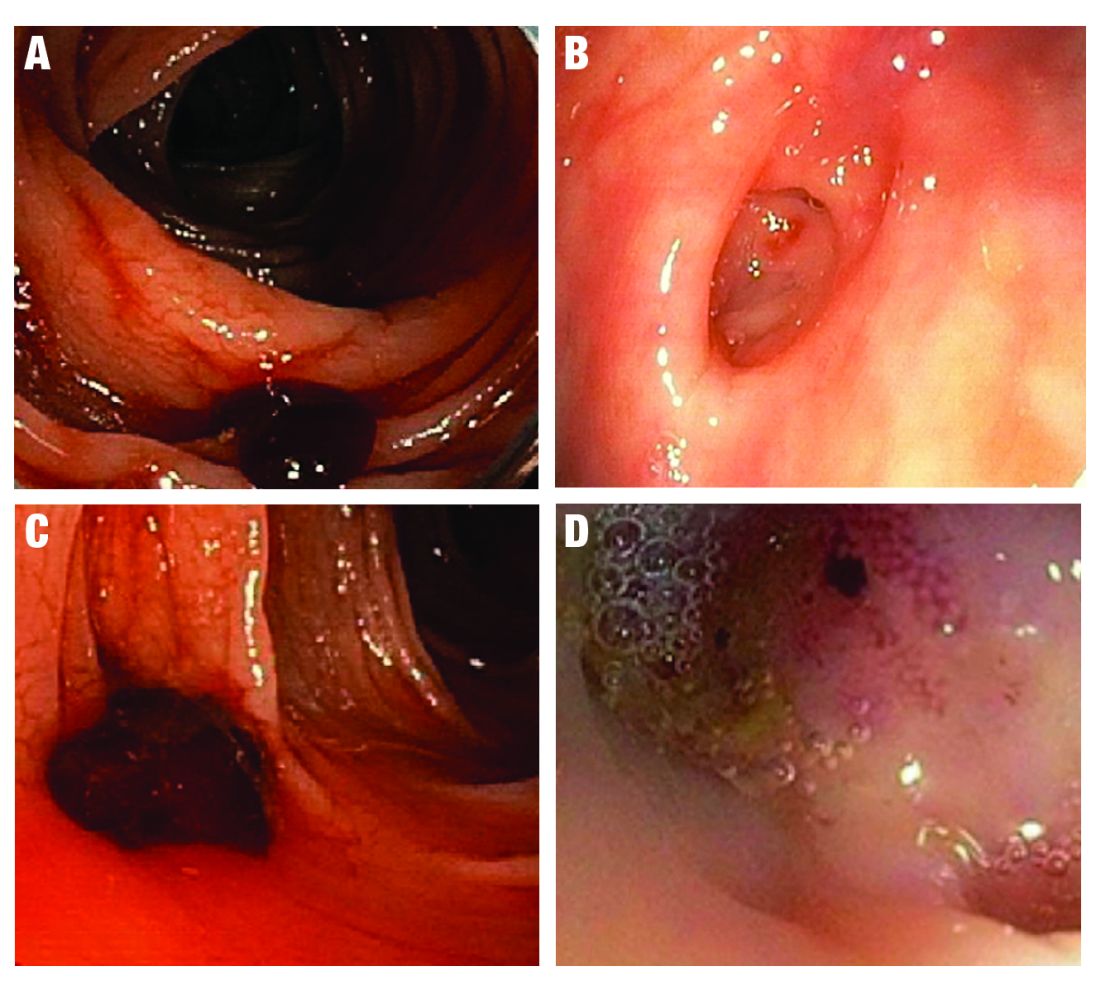

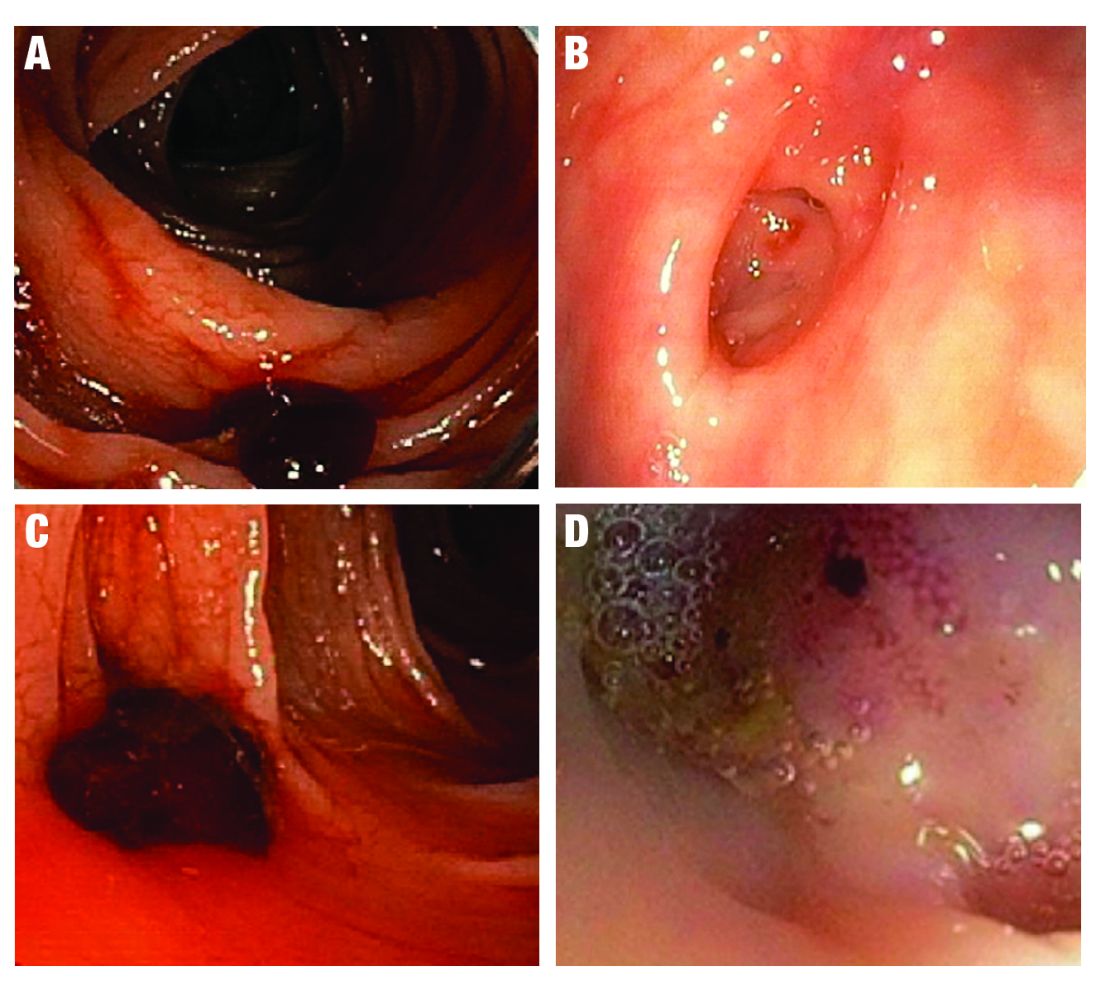

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

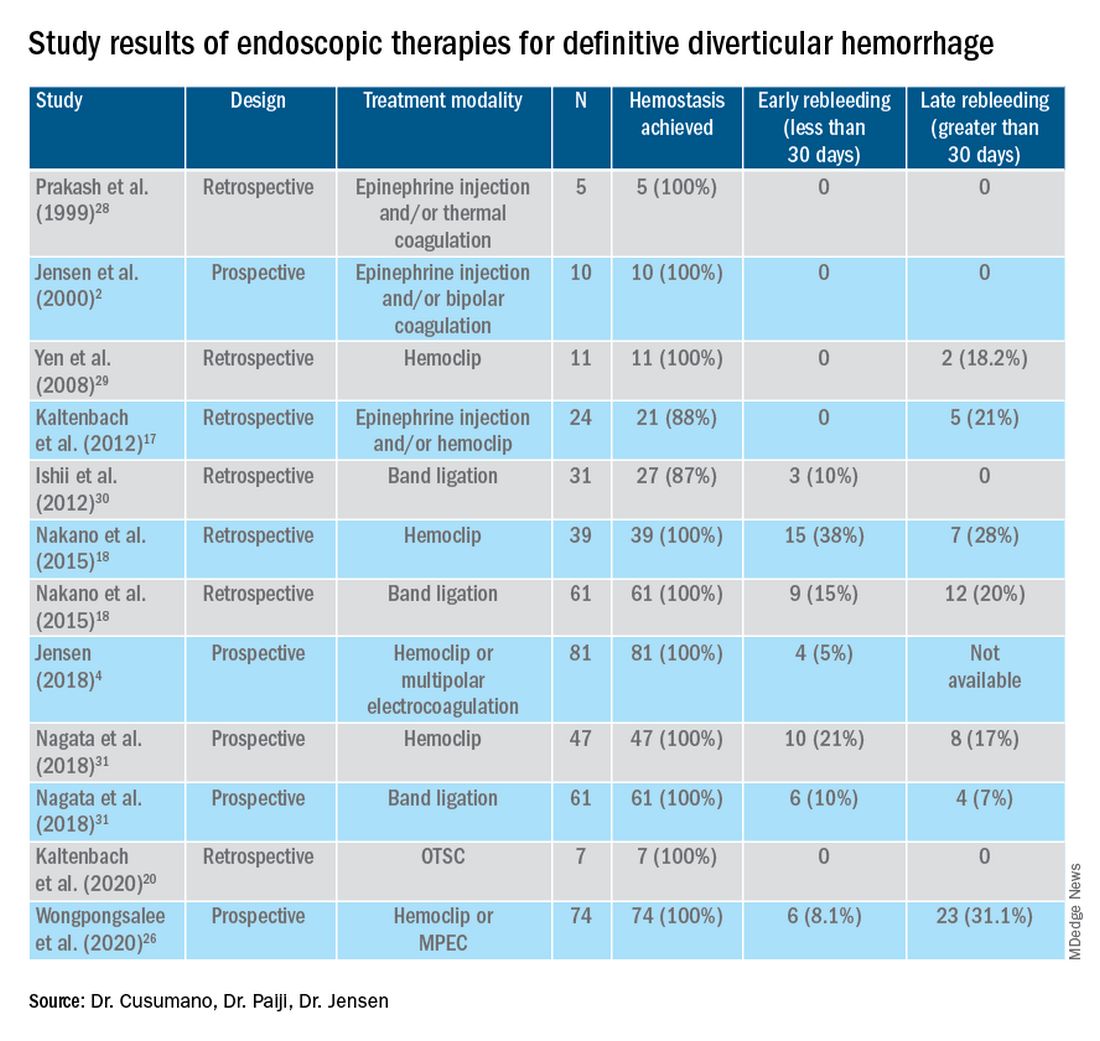

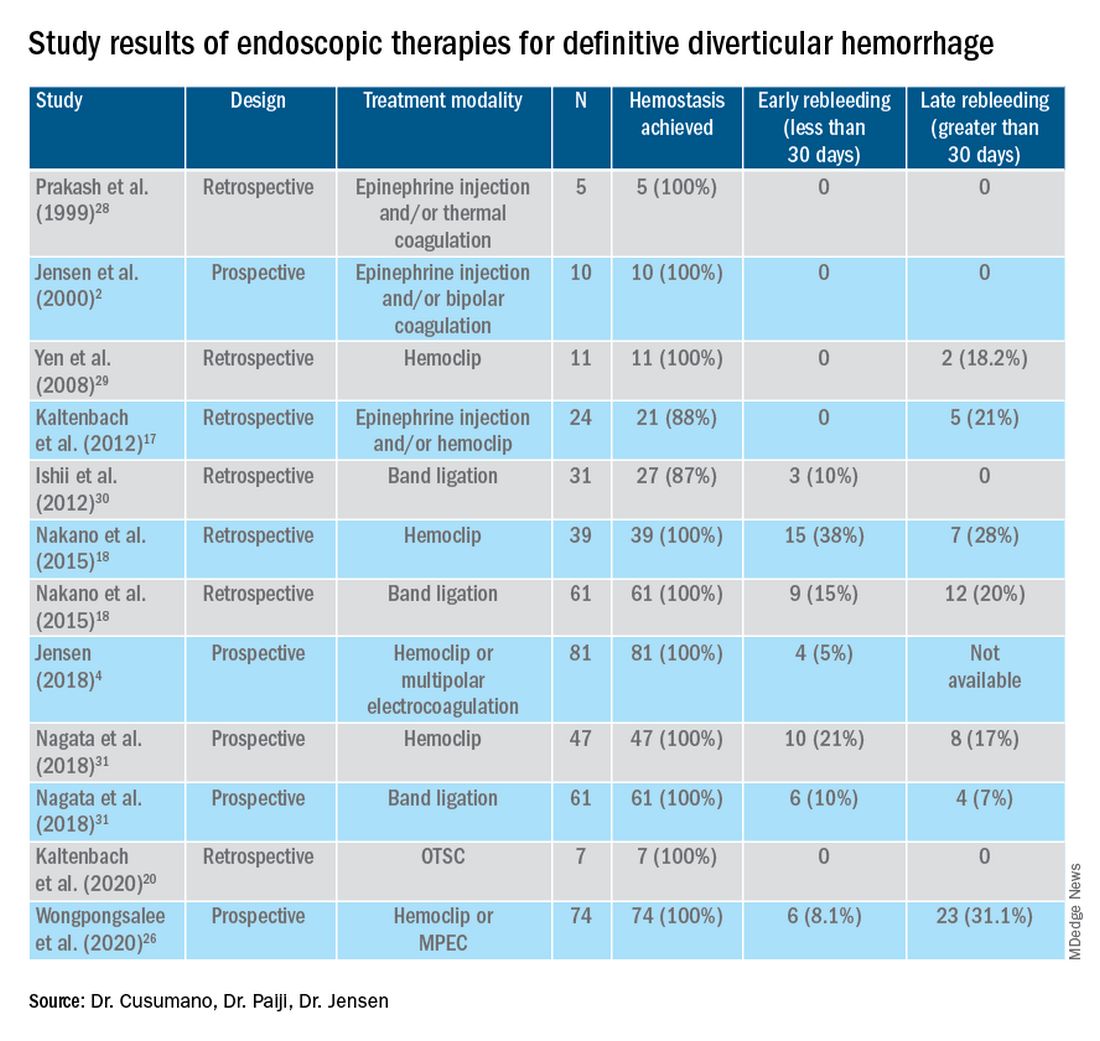

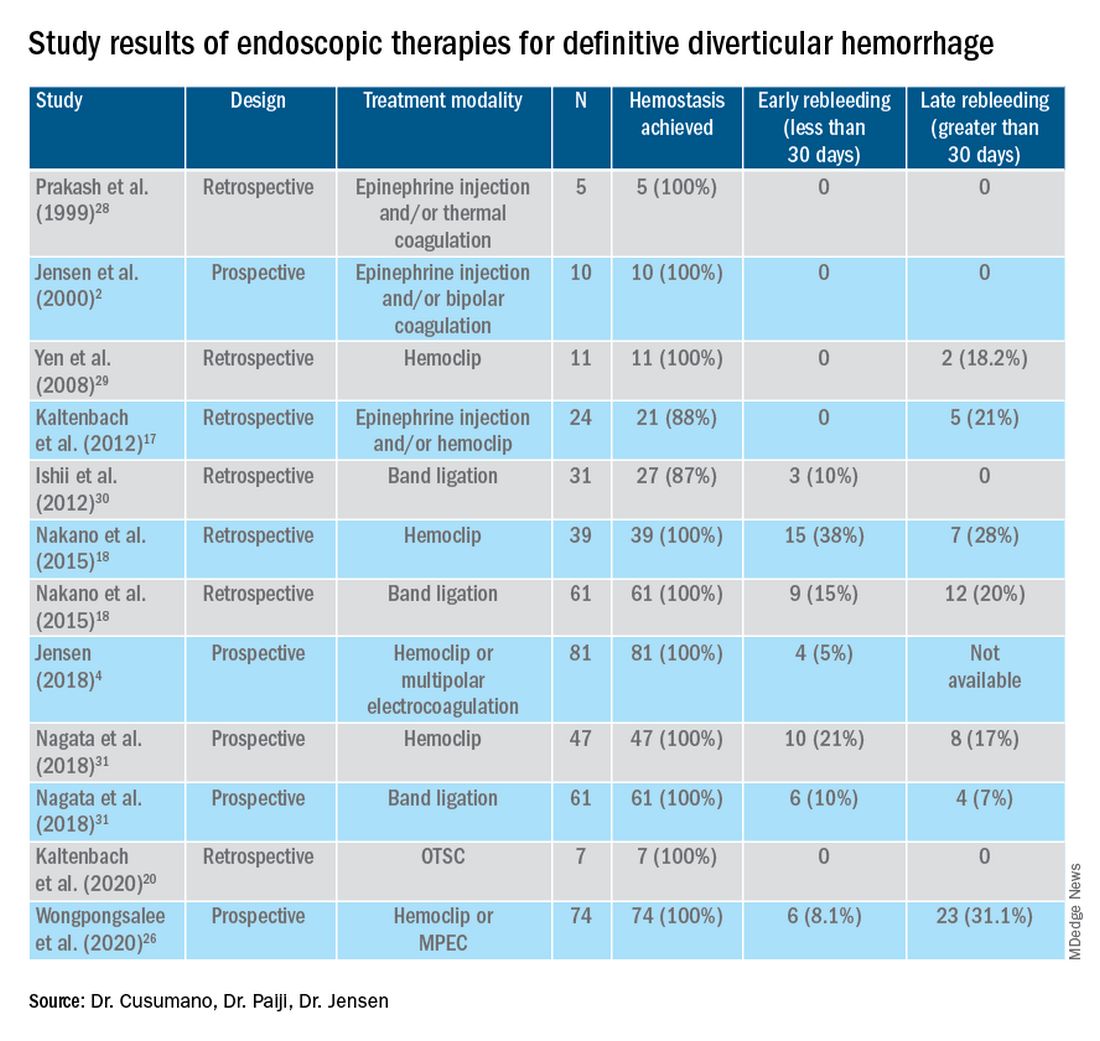

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.