User login

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

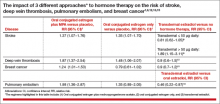

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.