User login

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

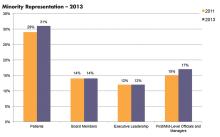

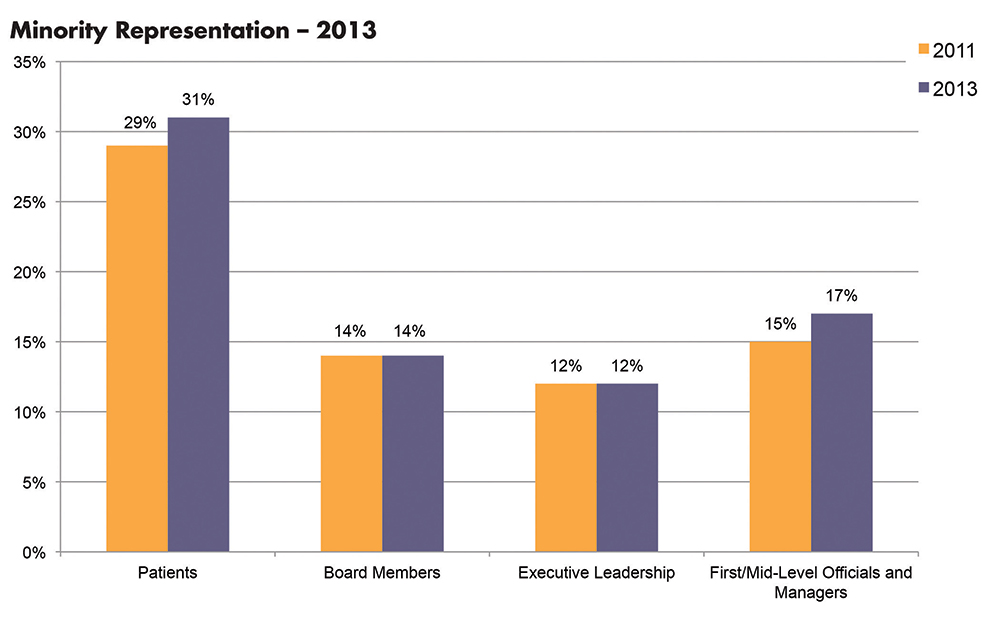

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.