User login

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

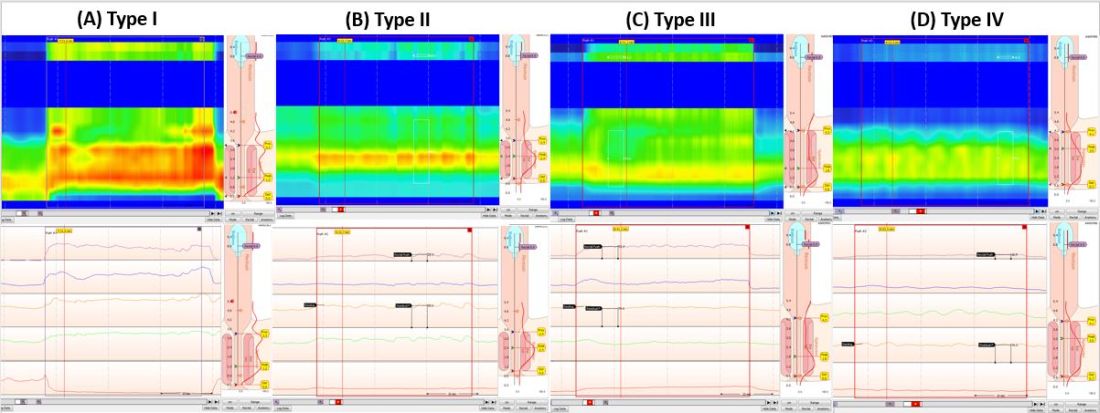

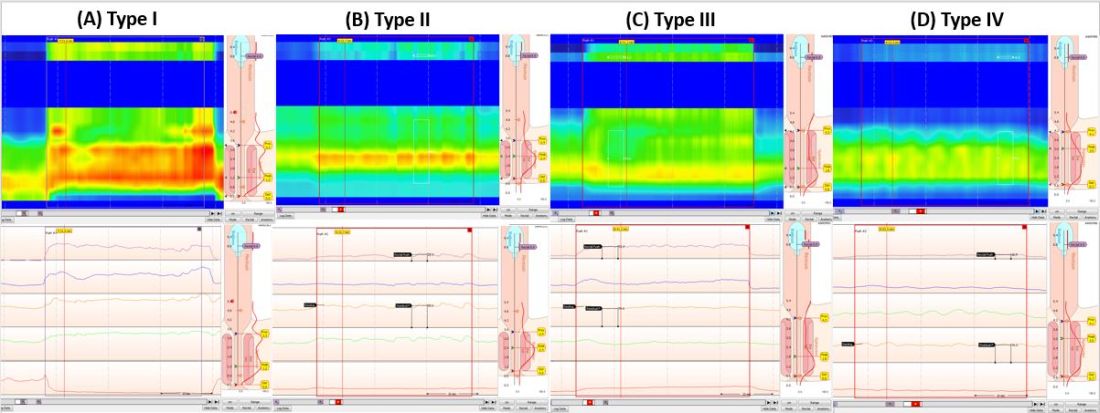

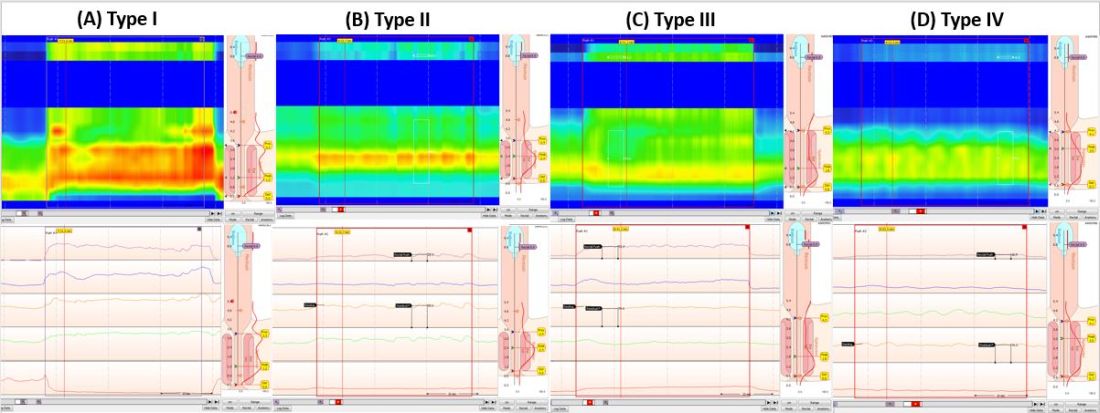

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.

- Inability to evacuate or retention of 50% or more of barium during defecography. (Some institutions use a prolonged colonic transit time: greater than 5 markers or 20% or higher marker retention on a plain abdominal x-Ray at 120 hours after ingestion of one radio-opaque marker capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers.)

Treatment of DD

The treatment modalities for DD depend on several factors: patient’s age, comorbidities, underlying pathophysiology, and patient expectations. Treatment options include standard management of constipation, but biofeedback therapy is the mainstay.

Standard management

Medications that cause or worsen constipation should be avoided. The patient should consume adequate fluid and exercise regularly. Patients should receive instructions for timed toilet training (twice daily, 30 minutes after meals). Patients should push at about 50%-70% of their ability for no longer than 5 minutes and avoid postponing defecation or use of digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation.42 The patients should take 25 g of soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium) daily. Of note, the benefits of fiber can take days to weeks44 and may be limited in patients with STC and DD.45 Medications including laxatives and intestinal secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide), and enterokinetic agents (prucalopride) can be used as adjunct therapy for management of DD.42 Their use is titrated during and after biofeedback therapy and may decrease after successful treatment.46

Biofeedback therapy

Biofeedback therapy involves operant conditioning techniques using either a solid state anorectal manometry system, electromyography, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices.42,47 The goals of biofeedback therapy are to correct the abdominal pelvic muscle discoordination during defecation and improve rectal sensation to stool if impaired. Biofeedback therapy involves patient education and active training (typically six sessions, 1-2 weeks apart, with each about 30-60 minutes long), followed by a reinforcement stage (three sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months), though there are variations in training protocols.42

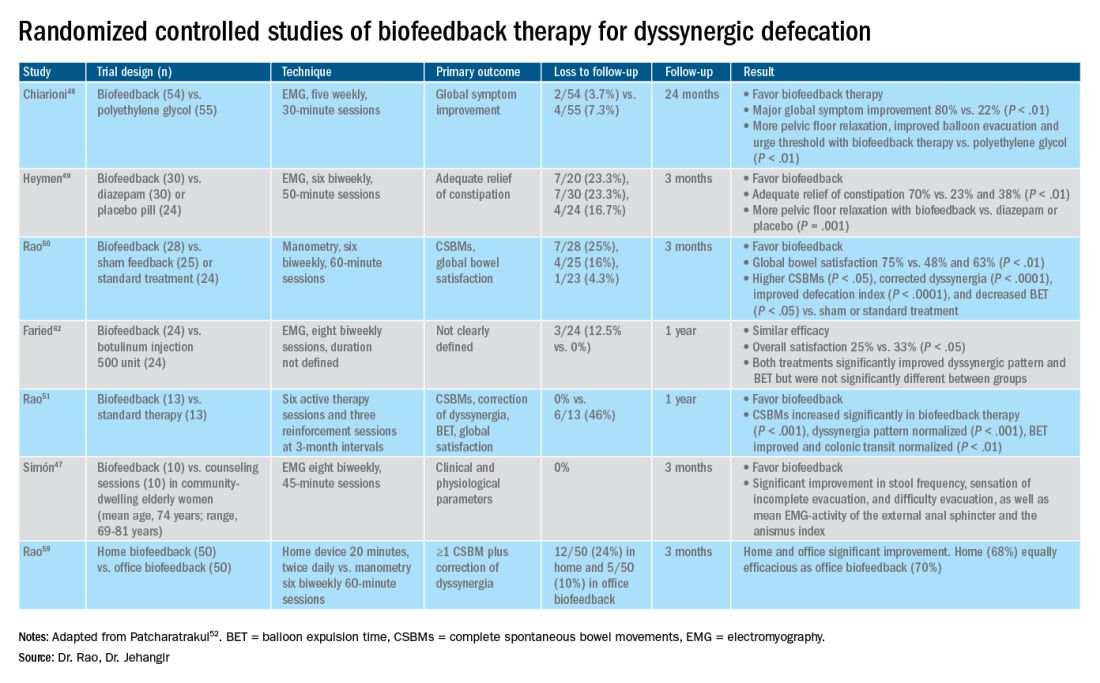

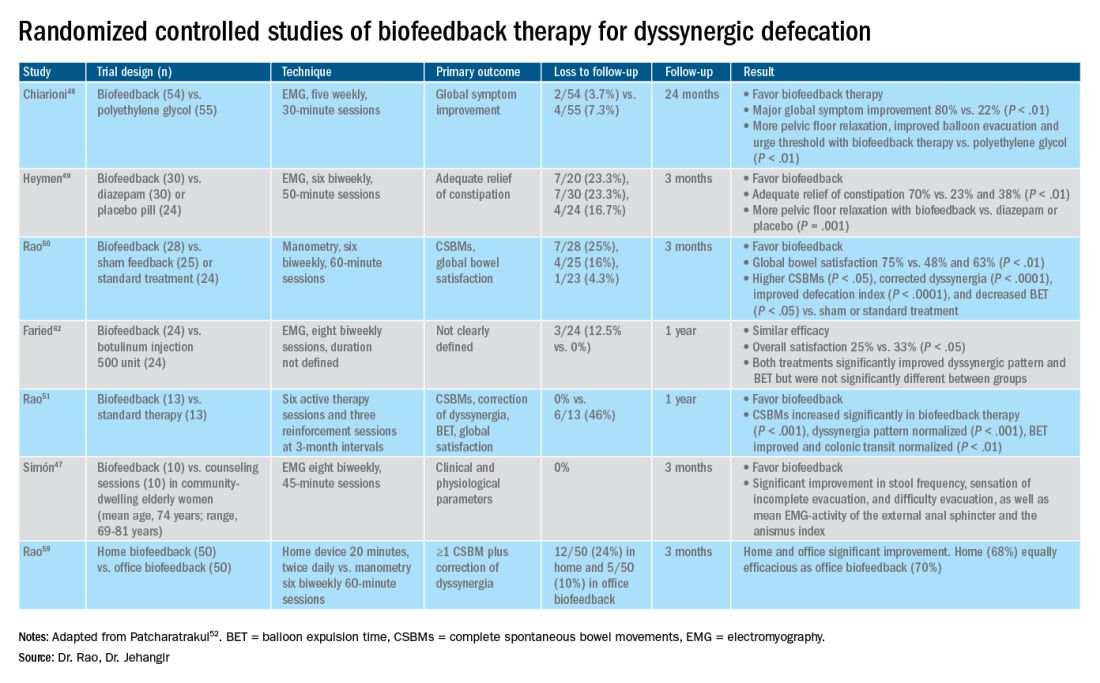

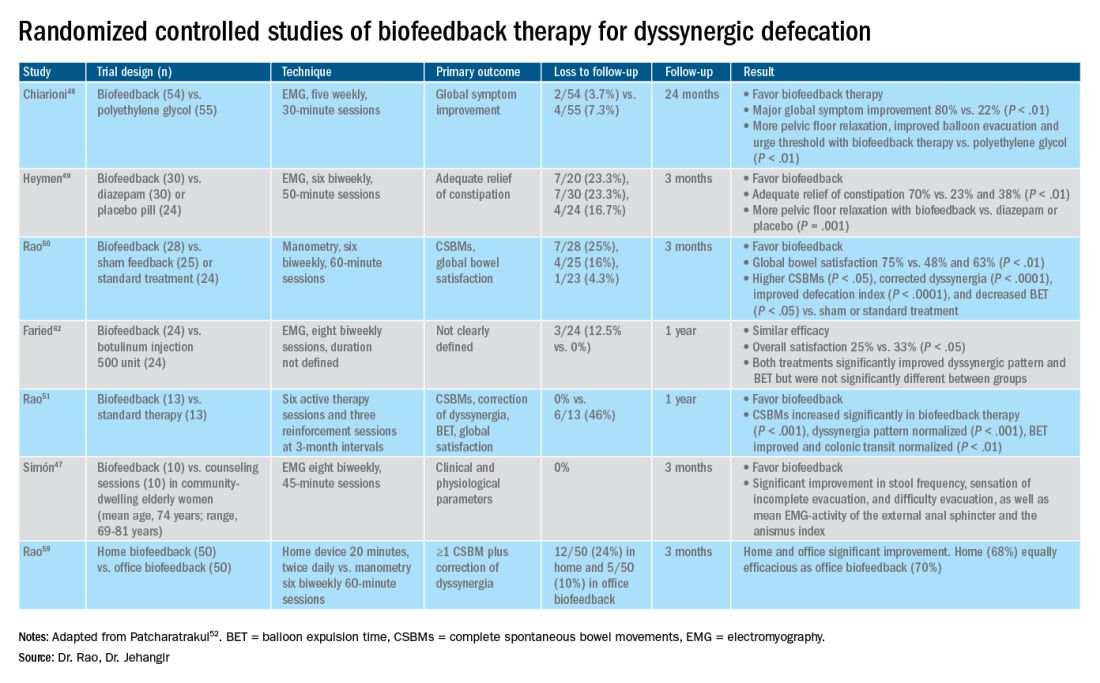

The success of biofeedback therapy depends on the patient’s motivation and the therapist’s skills.42 Compared with standard therapy (diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy), biofeedback therapy provides sustained improvement of bowel symptoms and anorectal function. Up to 70%-80% of DD patients show significant improvement of symptoms in randomized controlled trials (Table).48-52 Biofeedback therapy may also improve dyspeptic symptoms.53 Patients with harder stool consistency, greater willingness to participate, lower baseline bowel satisfaction, lower baseline anal sphincter relaxation, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, as well as patients who used digital maneuvers for defection, more commonly respond to biofeedback therapy.54,55 Longstanding laxative use has been associated with decreased response to biofeedback therapy.56 In patients with rectal hyposensitivity, barostat-assisted sensory training is more effective than a hand-held syringe technique.30 In patients with constipation predominant IBS and rectal hyposensitivity, sensory adaption training is more efficacious and better tolerated than escitalopram.30 Biofeedback therapy was afforded a grade A recommendation for treatment of DD by the American and European Societies of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.57

The access to office-based biofeedback therapy may be limited because of costs and low availability. The time required to attend multiple sessions may be burdensome for some patients, especially if they are taking time off from work. A recent study showed that patients with higher level of education may be less likely to adhere to biofeedback therapy.58 Recently, home biofeedback was shown to be noninferior to office biofeedback and was more cost-effective, which provides an alternative option for treating more patients.59

Endoscopic/surgical options

Other less effective treatment options for DD include botulinum toxin injection and myectomy.60-62 Botulinum toxin injection appears to have mixed effects with less than 50% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement, and it may cause fecal incontinence.60,63

Conclusion

DD is a common yet poorly recognized cause of constipation. Its clinical presentation overlaps with other lower-GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires detailed history, digital rectal examination, prospective stool diaries, anorectal manometry, and balloon expulsion tests. Biofeedback therapy offers excellent and sustained symptomatic improvement; however, access to office-based biofeedback is limited, and there is an urgent need for home-based biofeedback therapy programs.59

Dr. Rao is J. Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair, professor of medicine, director of neurogastroenterology/motility, and director of digestive health at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center Augusta (Georgia) University. He is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK121003-02 and U01DK115572. Dr. Jehangir is a gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center at Augusta University. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Peery AF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3 .

2. Curtin B, et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 30;26(4):423-36.

3. Suares NC & Ford AC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1582-91.

4. Mertz H, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):609-15.

5. Rao SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1042-50.

6. Rao SSC, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680-5.

7. Nojkov B, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(11):1772-7.

8. Heaton KW, et al. Gut. 1992;33(6):818-24.

9. Prichard DO & Bharucha AE. 2018 Oct 15;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1640.

10. Ashraf W, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):26-32.

11. Agachan F, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-5.

12. Frank L, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870-7.

13. Marquis P, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540-51.

14. Yan Y, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-400.

15. Rao SSC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):635-8.

16. Tantiphlachiva K, et al. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955-60.

17. Carrington EV, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(5):309-23.

18. Tetangco EP, et al. Performing and analyzing high-resolution anorectal manometry. NeuroGastroLatam Rev. 2018;2:120-32.

19. Lee YY, et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(12):360.

20. Sharma M, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(10):e13910.

21. Rao SSC, et al.. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2790-6.

22. Carrington EV, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13679.

23. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):569-86, viii.

24. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S158-9.

25. Guinet A, et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):507-13.

26. Rattan S, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):43-50.

27. Remes-Troche JM & Rao SSC. 2008;2(3):323-35.

28. Zaafouri H, et al..Int J Surgery. 2015. 2(1):9-17.

29. Remes-Troche JM, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1047-54.

30. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S-363.

31. Yu T, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(19):e3667.

32. Gladman MA, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(5):508-16, e4-5.

33. Lee KJ, et al. Digestion. 2006;73(2-3):133-41 .

34. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(5):553-9.

35. Coss-Adame E, et al.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1143-1150.e1.

36. Chiarioni G, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2049-54.

37. Gu G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-545–S-546.

38. Savoye-Collet C, et al.. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):553-67, viii.

39. Videlock EJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):509-20.

40. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):589-96.

41. Wald A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141-57 ; (Quiz) 1058.

42. Rao SSC & Patcharatrakul T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423-35.

43. Rao SS, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. S0016-5085(16)00175-X.

44. Bharucha AE, et al.. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218-38.

45. Voderholzer WA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):95-8.

46. Lee HJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):787-95.

47. Simón MA & Bueno AM. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):e90-4.

48. Chiarioni G,et al.. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657-64.

49. Heymen S, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428-41.

50. Rao SSC, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331-8.

51. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890-6.

52. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Biofeedback therapy. In Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. India: Stacy Masucci; 2020:517-32.

53. Huaman J-W, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2463-2470.e1.

54. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):715-21.

55. Chaudhry A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-382–S-383.

56. Shim LSE, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1245-51.

57. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(5):594-609.

58. Jangsirikul S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-383.

59. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):938-44.

60. Ron Y, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1821-6.

61. Podzemny V, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1053-60.

62. Faried M, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235-43.

63. Hallan RI, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(8613):714-7.

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.

- Inability to evacuate or retention of 50% or more of barium during defecography. (Some institutions use a prolonged colonic transit time: greater than 5 markers or 20% or higher marker retention on a plain abdominal x-Ray at 120 hours after ingestion of one radio-opaque marker capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers.)

Treatment of DD

The treatment modalities for DD depend on several factors: patient’s age, comorbidities, underlying pathophysiology, and patient expectations. Treatment options include standard management of constipation, but biofeedback therapy is the mainstay.

Standard management

Medications that cause or worsen constipation should be avoided. The patient should consume adequate fluid and exercise regularly. Patients should receive instructions for timed toilet training (twice daily, 30 minutes after meals). Patients should push at about 50%-70% of their ability for no longer than 5 minutes and avoid postponing defecation or use of digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation.42 The patients should take 25 g of soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium) daily. Of note, the benefits of fiber can take days to weeks44 and may be limited in patients with STC and DD.45 Medications including laxatives and intestinal secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide), and enterokinetic agents (prucalopride) can be used as adjunct therapy for management of DD.42 Their use is titrated during and after biofeedback therapy and may decrease after successful treatment.46

Biofeedback therapy

Biofeedback therapy involves operant conditioning techniques using either a solid state anorectal manometry system, electromyography, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices.42,47 The goals of biofeedback therapy are to correct the abdominal pelvic muscle discoordination during defecation and improve rectal sensation to stool if impaired. Biofeedback therapy involves patient education and active training (typically six sessions, 1-2 weeks apart, with each about 30-60 minutes long), followed by a reinforcement stage (three sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months), though there are variations in training protocols.42

The success of biofeedback therapy depends on the patient’s motivation and the therapist’s skills.42 Compared with standard therapy (diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy), biofeedback therapy provides sustained improvement of bowel symptoms and anorectal function. Up to 70%-80% of DD patients show significant improvement of symptoms in randomized controlled trials (Table).48-52 Biofeedback therapy may also improve dyspeptic symptoms.53 Patients with harder stool consistency, greater willingness to participate, lower baseline bowel satisfaction, lower baseline anal sphincter relaxation, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, as well as patients who used digital maneuvers for defection, more commonly respond to biofeedback therapy.54,55 Longstanding laxative use has been associated with decreased response to biofeedback therapy.56 In patients with rectal hyposensitivity, barostat-assisted sensory training is more effective than a hand-held syringe technique.30 In patients with constipation predominant IBS and rectal hyposensitivity, sensory adaption training is more efficacious and better tolerated than escitalopram.30 Biofeedback therapy was afforded a grade A recommendation for treatment of DD by the American and European Societies of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.57

The access to office-based biofeedback therapy may be limited because of costs and low availability. The time required to attend multiple sessions may be burdensome for some patients, especially if they are taking time off from work. A recent study showed that patients with higher level of education may be less likely to adhere to biofeedback therapy.58 Recently, home biofeedback was shown to be noninferior to office biofeedback and was more cost-effective, which provides an alternative option for treating more patients.59

Endoscopic/surgical options

Other less effective treatment options for DD include botulinum toxin injection and myectomy.60-62 Botulinum toxin injection appears to have mixed effects with less than 50% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement, and it may cause fecal incontinence.60,63

Conclusion

DD is a common yet poorly recognized cause of constipation. Its clinical presentation overlaps with other lower-GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires detailed history, digital rectal examination, prospective stool diaries, anorectal manometry, and balloon expulsion tests. Biofeedback therapy offers excellent and sustained symptomatic improvement; however, access to office-based biofeedback is limited, and there is an urgent need for home-based biofeedback therapy programs.59

Dr. Rao is J. Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair, professor of medicine, director of neurogastroenterology/motility, and director of digestive health at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center Augusta (Georgia) University. He is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK121003-02 and U01DK115572. Dr. Jehangir is a gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center at Augusta University. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Peery AF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3 .

2. Curtin B, et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 30;26(4):423-36.

3. Suares NC & Ford AC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1582-91.

4. Mertz H, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):609-15.

5. Rao SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1042-50.

6. Rao SSC, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680-5.

7. Nojkov B, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(11):1772-7.

8. Heaton KW, et al. Gut. 1992;33(6):818-24.

9. Prichard DO & Bharucha AE. 2018 Oct 15;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1640.

10. Ashraf W, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):26-32.

11. Agachan F, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-5.

12. Frank L, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870-7.

13. Marquis P, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540-51.

14. Yan Y, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-400.

15. Rao SSC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):635-8.

16. Tantiphlachiva K, et al. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955-60.

17. Carrington EV, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(5):309-23.

18. Tetangco EP, et al. Performing and analyzing high-resolution anorectal manometry. NeuroGastroLatam Rev. 2018;2:120-32.

19. Lee YY, et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(12):360.

20. Sharma M, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(10):e13910.

21. Rao SSC, et al.. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2790-6.

22. Carrington EV, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13679.

23. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):569-86, viii.

24. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S158-9.

25. Guinet A, et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):507-13.

26. Rattan S, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):43-50.

27. Remes-Troche JM & Rao SSC. 2008;2(3):323-35.

28. Zaafouri H, et al..Int J Surgery. 2015. 2(1):9-17.

29. Remes-Troche JM, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1047-54.

30. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S-363.

31. Yu T, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(19):e3667.

32. Gladman MA, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(5):508-16, e4-5.

33. Lee KJ, et al. Digestion. 2006;73(2-3):133-41 .

34. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(5):553-9.

35. Coss-Adame E, et al.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1143-1150.e1.

36. Chiarioni G, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2049-54.

37. Gu G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-545–S-546.

38. Savoye-Collet C, et al.. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):553-67, viii.

39. Videlock EJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):509-20.

40. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):589-96.

41. Wald A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141-57 ; (Quiz) 1058.

42. Rao SSC & Patcharatrakul T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423-35.

43. Rao SS, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. S0016-5085(16)00175-X.

44. Bharucha AE, et al.. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218-38.

45. Voderholzer WA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):95-8.

46. Lee HJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):787-95.

47. Simón MA & Bueno AM. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):e90-4.

48. Chiarioni G,et al.. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657-64.

49. Heymen S, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428-41.

50. Rao SSC, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331-8.

51. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890-6.

52. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Biofeedback therapy. In Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. India: Stacy Masucci; 2020:517-32.

53. Huaman J-W, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2463-2470.e1.

54. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):715-21.

55. Chaudhry A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-382–S-383.

56. Shim LSE, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1245-51.

57. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(5):594-609.

58. Jangsirikul S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-383.

59. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):938-44.

60. Ron Y, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1821-6.

61. Podzemny V, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1053-60.

62. Faried M, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235-43.

63. Hallan RI, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(8613):714-7.

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.

- Inability to evacuate or retention of 50% or more of barium during defecography. (Some institutions use a prolonged colonic transit time: greater than 5 markers or 20% or higher marker retention on a plain abdominal x-Ray at 120 hours after ingestion of one radio-opaque marker capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers.)

Treatment of DD

The treatment modalities for DD depend on several factors: patient’s age, comorbidities, underlying pathophysiology, and patient expectations. Treatment options include standard management of constipation, but biofeedback therapy is the mainstay.

Standard management

Medications that cause or worsen constipation should be avoided. The patient should consume adequate fluid and exercise regularly. Patients should receive instructions for timed toilet training (twice daily, 30 minutes after meals). Patients should push at about 50%-70% of their ability for no longer than 5 minutes and avoid postponing defecation or use of digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation.42 The patients should take 25 g of soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium) daily. Of note, the benefits of fiber can take days to weeks44 and may be limited in patients with STC and DD.45 Medications including laxatives and intestinal secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide), and enterokinetic agents (prucalopride) can be used as adjunct therapy for management of DD.42 Their use is titrated during and after biofeedback therapy and may decrease after successful treatment.46

Biofeedback therapy

Biofeedback therapy involves operant conditioning techniques using either a solid state anorectal manometry system, electromyography, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices.42,47 The goals of biofeedback therapy are to correct the abdominal pelvic muscle discoordination during defecation and improve rectal sensation to stool if impaired. Biofeedback therapy involves patient education and active training (typically six sessions, 1-2 weeks apart, with each about 30-60 minutes long), followed by a reinforcement stage (three sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months), though there are variations in training protocols.42

The success of biofeedback therapy depends on the patient’s motivation and the therapist’s skills.42 Compared with standard therapy (diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy), biofeedback therapy provides sustained improvement of bowel symptoms and anorectal function. Up to 70%-80% of DD patients show significant improvement of symptoms in randomized controlled trials (Table).48-52 Biofeedback therapy may also improve dyspeptic symptoms.53 Patients with harder stool consistency, greater willingness to participate, lower baseline bowel satisfaction, lower baseline anal sphincter relaxation, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, as well as patients who used digital maneuvers for defection, more commonly respond to biofeedback therapy.54,55 Longstanding laxative use has been associated with decreased response to biofeedback therapy.56 In patients with rectal hyposensitivity, barostat-assisted sensory training is more effective than a hand-held syringe technique.30 In patients with constipation predominant IBS and rectal hyposensitivity, sensory adaption training is more efficacious and better tolerated than escitalopram.30 Biofeedback therapy was afforded a grade A recommendation for treatment of DD by the American and European Societies of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.57

The access to office-based biofeedback therapy may be limited because of costs and low availability. The time required to attend multiple sessions may be burdensome for some patients, especially if they are taking time off from work. A recent study showed that patients with higher level of education may be less likely to adhere to biofeedback therapy.58 Recently, home biofeedback was shown to be noninferior to office biofeedback and was more cost-effective, which provides an alternative option for treating more patients.59

Endoscopic/surgical options

Other less effective treatment options for DD include botulinum toxin injection and myectomy.60-62 Botulinum toxin injection appears to have mixed effects with less than 50% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement, and it may cause fecal incontinence.60,63

Conclusion

DD is a common yet poorly recognized cause of constipation. Its clinical presentation overlaps with other lower-GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires detailed history, digital rectal examination, prospective stool diaries, anorectal manometry, and balloon expulsion tests. Biofeedback therapy offers excellent and sustained symptomatic improvement; however, access to office-based biofeedback is limited, and there is an urgent need for home-based biofeedback therapy programs.59

Dr. Rao is J. Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair, professor of medicine, director of neurogastroenterology/motility, and director of digestive health at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center Augusta (Georgia) University. He is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK121003-02 and U01DK115572. Dr. Jehangir is a gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center at Augusta University. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Peery AF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3 .

2. Curtin B, et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 30;26(4):423-36.

3. Suares NC & Ford AC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1582-91.

4. Mertz H, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):609-15.

5. Rao SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1042-50.

6. Rao SSC, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680-5.

7. Nojkov B, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(11):1772-7.

8. Heaton KW, et al. Gut. 1992;33(6):818-24.

9. Prichard DO & Bharucha AE. 2018 Oct 15;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1640.

10. Ashraf W, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):26-32.

11. Agachan F, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-5.

12. Frank L, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870-7.

13. Marquis P, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540-51.

14. Yan Y, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-400.

15. Rao SSC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):635-8.

16. Tantiphlachiva K, et al. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955-60.

17. Carrington EV, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(5):309-23.

18. Tetangco EP, et al. Performing and analyzing high-resolution anorectal manometry. NeuroGastroLatam Rev. 2018;2:120-32.

19. Lee YY, et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(12):360.

20. Sharma M, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(10):e13910.

21. Rao SSC, et al.. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2790-6.

22. Carrington EV, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13679.

23. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):569-86, viii.

24. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S158-9.

25. Guinet A, et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):507-13.

26. Rattan S, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):43-50.

27. Remes-Troche JM & Rao SSC. 2008;2(3):323-35.

28. Zaafouri H, et al..Int J Surgery. 2015. 2(1):9-17.

29. Remes-Troche JM, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1047-54.

30. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S-363.

31. Yu T, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(19):e3667.

32. Gladman MA, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(5):508-16, e4-5.

33. Lee KJ, et al. Digestion. 2006;73(2-3):133-41 .

34. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(5):553-9.

35. Coss-Adame E, et al.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1143-1150.e1.

36. Chiarioni G, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2049-54.

37. Gu G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-545–S-546.

38. Savoye-Collet C, et al.. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):553-67, viii.

39. Videlock EJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):509-20.

40. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):589-96.

41. Wald A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141-57 ; (Quiz) 1058.

42. Rao SSC & Patcharatrakul T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423-35.

43. Rao SS, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. S0016-5085(16)00175-X.

44. Bharucha AE, et al.. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218-38.

45. Voderholzer WA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):95-8.

46. Lee HJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):787-95.

47. Simón MA & Bueno AM. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):e90-4.

48. Chiarioni G,et al.. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657-64.

49. Heymen S, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428-41.

50. Rao SSC, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331-8.

51. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890-6.

52. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Biofeedback therapy. In Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. India: Stacy Masucci; 2020:517-32.

53. Huaman J-W, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2463-2470.e1.

54. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):715-21.

55. Chaudhry A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-382–S-383.

56. Shim LSE, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1245-51.

57. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(5):594-609.

58. Jangsirikul S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-383.

59. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):938-44.

60. Ron Y, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1821-6.

61. Podzemny V, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1053-60.

62. Faried M, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235-43.

63. Hallan RI, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(8613):714-7.