User login

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

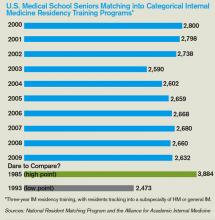

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.

Indu Michael remembers the one-page medical field survey she filled out around this time last year. A pre-med student at the University of California at Los Angeles, she provided the correct job descriptions for surgeons, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, psychiatrists, and internal medicine physicians. Only one medical specialty stumped her.

“I had no idea what a hospitalist did,” says Michael, 21, a senior.

The anonymous survey was part of the application and interview process for the Undergraduate Preceptorship in Internal Medicine (UPIM), a program that was launched last summer at UCLA Medical Center. By the time Michael finished the three-week program in early September, she had a complete understanding of what hospitalists do. She also says she’s leaning toward an internal medicine (IM) career—and might become a hospitalist.

“I’m seriously thinking [Hem-Onc] may not be the direction I want to take,” Michael says. “I realized oncologists are mainly consultative doctors and it’s really the general medicine team that does the medicine.”

Those kind of comments are music to Nasim Afsar-manesh’s ear. Dr. Afsar-manesh, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at UCLA, developed the UPIM program from scratch as a way to expose pre-med undergrads to internal medicine. The ultimate goal, of course, is steering them toward an internist career. She is well aware of medical students’ declining interest in IM, and she believes outreach to undergrads and first-year medical students will help reverse the trend.

“Undergraduates are like sponges,” Dr. Afsar-manesh says. “They are so genuinely excited about the possibilities of getting to do this stuff. … You can appeal to their idealism.” She created the program because “the general field of medicine has become so complex that students who are thinking about making it a career don’t have a good chance to see what the day-to-day practicing of medicine is like.”

HM Test Drive

Michael was one of seven students in the inaugural UPIM session. The program is open to UCLA undergrads who volunteer at least 80 hours at the medical center and pre-med students at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Afsar-manesh received her undergraduate degree. Seventeen students applied for the first session; the seven who were selected were chosen based on their motivation, maturity, and enthusiasm for medicine. The plan is simple: UPIM aims to offer an early spark of excitement that will stay with students and serve as positive reinforcement as they proceed through medical school and confront the challenges of an IM career.

UPIM participants were integrated into teams of attendings, residents, and medical school students, and they spent time on hospital units and subspecialty consult services. The undergrads observed residents in their patient evaluations, daily rounds, and discussions with patient families. They witnessed a number of procedures, including central-line placement and bone-marrow biopsies. Although the attendings and residents weren’t required to teach the undergrads, many volunteered a significant amount of their time, Dr. Afsar-manesh says. Some of the students spent night shifts at the hospital.

“The students felt they had participated in something special. They felt the experience had overshadowed anything they had previously done,” says Dr. Afsar-manesh, a member of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee. “I think it’s a program that can really quickly grow.”

Every Friday, undergrads participated in a teaching session, during which they had to present a medically, socially, or ethically challenging case from the previous week. They received lectures on common HM topics, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The sessions featured guest speakers who touched on career options in IM and HM, research careers, tips for getting into medical school, and international health issues.

“I loved the patient interaction, as well as discussing a case with fellow students. I didn’t even mind the long hours,” says Stacey Yudin, 23, a senior pre-med student at UCLA. “While on rounds, medical students and doctors took the time to explain concepts while we were scurrying from patient to patient. The program gave me the opportunity to test-drive my dream. We always test-drive a car before we hand over thousands of dollars for it. Shouldn’t future medical students be able to at least safely experience the practice of medicine?”

Round Two: Upgrade

This summer, Dr. Afsar-manesh is improving the student presentation and guest speaker component of the Friday sessions. She will add QI and patient-safety sessions. But the biggest change to the program is expansion, as she and fellow UCLA hospitalist Ed Ha, MD, will offer a summer session for medical students between their first and second years.

Dr. Afsar-manesh also is busy reaching out to other academic IM and HM programs interested in establishing a preceptorship program. So far, she’s made headway with 10 institutions, including Northwestern University, Stanford University, the University of Michigan Health System, and a handful of the campuses within the University of California system. She’s invited the institutions to participate in a research collaborative to combine their data on program results. “We ultimately need to see how many participants will go into IM and compare that to the national numbers. That will take years,” she says.

Uphill Battle

Mark Schwartz, MD, an associate professor in the division of general IM at New York University’s School of Medicine, believes UPIM and programs like it will help—even if only marginally—address the declining interest in IM careers among medical students.

“It will take more than tinkering around in the educational environment,” says Dr. Schwartz, who believes workforce planning, changes in reimbursement, and redesigning medical practices are essential to recruiting medical students to internal medicine (see “A Good Start, But Not Enough”).

Nevertheless, SHM is ready to support a combined IM/HM preceptorship program that targets medical school students in their first and second years, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM. The society already has assigned staff to manage the project and named Dr. Afsar-manesh as the lead physician. The plan is to track preceptorship participants as they make their way through medical school and residency, and see if the program changes their attitudes toward IM careers.

Even though the number of medical students who aspire to hospitalist careers continues to increase every year, SHM believes it must move to counteract the lackluster IM numbers, because that is where most medical students are introduced to HM, Dr. Wellikson says. “The problem of people not picking internal medicine could affect hospital medicine down the road,” he says. “We can’t sit passively by and see who picks to be a hospitalist. We believe we need to be active.”

One of the last things Dr. Afsar-manesh did at the conclusion of the inaugural UPIM program was collect the students’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers so she can stay in touch and track their career paths. The UPIM survey results give her hope: After UPIM, 100% of the students were “extremely confident” in their decision to pursue medicine; 57% indicated they were “very likely” to consider IM as a specialty; and 47% were “very likely” to think about HM.

“This program is a great way to encourage students to enter into internal medicine,” Yudin says. “I am sure that all my subsequent experiences working in a hospital will be measured against my first experience rounding with the IM department.” It seems as though the student took the words right out of the doctor’s mouth. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Reference

- Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154-1164.