User login

What do you tell your patients who are self-medicating with herbal remedies? Can dietary supplements safely improve mood disorders, insomnia, and other psychiatric complaints?

Evidence is limited on complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), their active components, pharmacokinetics/dynamics, adverse effects, drug interactions, and therapeutic outcomes. Based on our review of trial data, case reports, and an NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) survey,1 we offer information to help you:

- identify patients using dietary supplements

- avoid serious interactions with common psychotropics

- counsel patients on the efficacy and safety of ginkgo biloba, St. John’s wort, kava kava, and valerian (Table 1).

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ASK

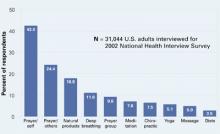

One-third of Americans who took part in the NCCAM survey reported using CAM. After prayer—the number-one CAM—respondents said they most often used natural products such as herbals, botanicals, nutraceuticals, phytomedicinals, and dietary supplements (Figure).1

Table 1

4 herbal supplements with purported psychotropic effects

| Herb | Promoted use | Safety | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba | Dementia, memory | Bleeding complications, drug interactions a concern | Some data support a trial in dementia; beware of safety concerns |

| St. John’s wort | Depression | Substantial drug interactions | Use not recommended because of wide-ranging drug interactions |

| Kava kava | Anxiety | Hepatotoxicity risk, drug interactions; off market in Europe and Canada | Use not recommended because of safety issues |

| Valerian | Insomnia | Limited data available | Benign (?); monitor for possible adverse events or drug interactions |

Patients tend to use CAM to treat chronic medical conditions such as back pain, depression, and anxiety.1 Although CAM use is common, only 38% of patients say they disclose using CAM to their physicians.2 These use and disclosure patterns are similar in psychiatry.3

Herbal products may produce symptoms that mimic those of mental illnesses, such as psychosis and mania, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Abruptly stopping some herbs can produce withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine and antidepressant cessation. Supplements also can inhibit or augment prescribed psychotropics’ effects, and notable consequences include the potential for serotonin syndrome with use of St. John’s wort.

The key to learning about a patient’s use of dietary supplements is to ask. Patients commonly say they do not tell their doctors about using dietary supplements because “it wasn’t important for the doctor to know” or “the doctor never asked.”4,5 Ten tips for discussing nutritional supplements with patients are shown in the Box.

Buyer—and psychiatrist—beware. Because of dietary supplements’ regulatory status, physicians and patients need to learn as much as they can about these products’ documented safety and efficacy. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act passed by Congress in 1994 does not require manufacturers to prove their products are safe or effective before marketing them. They also can make claims that suggest uses in physical/emotional structure and function, such as “helps maintain a healthy emotional outlook.”

The FDA bears the burden of proof regarding safety and can remove a dietary supplement from the market only after receiving documented adverse event information from the public.6 The FDA has confiscated herbal products containing prescription drugs and misidentified herbal components.

GINKGO BILOBA FOR DEMENTIA

Ginkgo biloba was the third most commonly used herbal product (21%) in the NCCAM survey. Ginkgo is promoted primarily for dementia, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and memory enhancement. The standardized ginkgo extract (EGb 761) contains several components to which its pharmacologic activity has been attributed. Its constituents are thought to act primarily through anticoagulant effects by inhibiting platelet-activating factor and cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. They also act through membrane stabilization, antioxidant properties, free-radical scavenging, and inhibition of beta-amyloid deposition.7

Efficacy. In patients with dementia, clinical trials using EGb 761 have shown small improvements in or maintenance of cognitive and social functioning, compared with placebo.8,9 The clinical significance of these findings is unclear, however. Ginkgo’s usefulness in enhancing memory is less certain. Controlled clinical trials are evaluating ginkgo’s efficacy in various conditions.10

Adverse effects. Bleeding complications are the primary concern with ginkgo biloba use, and caution is urged when it is taken concomitantly with aspirin or other antithrombotic drugs. Patients receiving warfarin should not take ginkgo because of the combined antiplatelet effects and ginkgo’s inhibition of warfarin metabolism and elimination.

Drug-herb interactions. One report showed that EGb 761 is a strong inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 2C9 enzyme system (CYP 2C9).11 Other identified inhibitors of CYP 2C9 are fluvoxamine (strong inhibitor), amiodarone, cimetidine, fluoxetine, and omeprazole. Drugs that serve as substrates for that system and can have decreased clearance include phenytoin, warfarin, amitriptyline, and diazepam;12 use caution, therefore, when you co-administer these drugs with ginkgo.

Figure 10 CAM therapies patients report using most often

CAM: Complimentary and alternative medicines

Source: Barnes T, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 27, 2004: Advance Data Report #343 (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad343.pdf) Dosage. The usual dosage for standardized ginkgo extract is 120 to 240 mg/d, given in divided doses. Improvements associated with ginkgo use usually are seen within 4 to 12 weeks after starting therapy.7 Consider discontinuing therapy if you see no results after that time. Little is known about ginkgo’s effect after 1 year of use.

Recommendation. Limited data show a slight benefit in treating dementia by slowing cognitive and behavioral decline, but ginkgo biloba cannot be recommended as a first-line treatment until further controlled trials are available.

- Broach the subject without being judgmental; nutritional supplement use is tied to a patient’s health beliefs

- Ask specifically about use of herbs, supplements, teas, elixirs, vitamins, etc., and document in the medical record at each visit

- Include in appointment reminders a request that patients bring all medicines, herbs, and supplements to appointments

- Segue into a discussion of supplements by noting their use by other patients with similar diagnoses

- Learn about and provide objective information on products

- Suggest use of single-ingredient products because:

- Suggest a symptom diary and a plan to discontinue a supplement if desired results are not seen

- Report suspected adverse events or drug interactions to the FDA

- Choose your battles carefully; testimonials and the placebo effect can strongly influence patients’ desire to continue using dietary supplements

- Remember: Patient safety is paramount

ST. JOHN’S WORT FOR DEPRESSION

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), used to treat mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety,13 is one of the most-recognized herbal remedies. It accounted for 12% of the natural products used in the NCCAM survey. Several clinical trials assessing St. John’s wort are in progress and include placebo-controlled evaluations in obsessive-compulsive disorder and social phobia.14

As with ginkgo, St. John’s wort has many proposed active constituents; most preparations are standardized based on a hypericin content of 0.3%. Its mechanism of action in depression is unclear but laboratory models hint that it may be related to very mild inhibition of:

- monoamine oxidase (MAO)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase(COMT)

- selective serotonin reuptake

- interleukin-6 release (thereby increasing corticotropin-releasing hormone levels)

- norepinephrine uptake.15

Efficacy. St. John’s wort has been studied in mild, moderate, and major depression and compared with placebo and prescription therapies. In treating mild and moderate depression, St. John’s wort has been more effective than placebo and equivalent to tricyclic antidepressants.16,17 Criticisms of these trials include lack of product standardization, lack of comparison with standard antidepressants at appropriate dosages, and small sample sizes. Larger trials comparing St. John’s wort with placebo and sertraline in treating major depression showed no difference in effect among the three.18,19

Adverse effects are generally infrequent and include insomnia, anxiety, GI upset, and photosensitivity reactions.20 St. John’s wort can induce hypomania and mania in patients with bipolar disorder and cause psychosis in schizophrenic patients.13

Drug-herb interactions. Of greatest concern with St. John’s wort use is the remarkable number of drug-herb interactions that have been identified (Table 2 and Table 3).13,21 The primary mechanisms appear to be substantial induction of CYP 3A4, induction of P-glycoprotein mediated drug elimination, and—to a lesser extent—induction of other CYP isoenzymes.22 Interactions resulting in serotonin syndrome have been documented, with restlessness, sweating, and agitation.23

The 3A4 isoenzyme metabolizes most drugs processed via the CYP system.12 Severe interactions seen with St. John’s wort include:

- reduced cyclosporine levels, resulting in heart transplant rejection in two patients

- reduced antiretroviral levels in HIV patients

- pregnancy in women taking oral contraceptives.

Enzyme induction may persist for as long as 14 days after patients stop taking St. John’s wort.

Dosage. The recommended St. John’s wort dosage (using standardized 0.3% hypericin content) is 300 mg 2 or 3 times daily. Dosages of 1,200 to 1,800 mg/d have been used.13,18 Benefits may not be seen for 2 to 3 weeks, and experience with use beyond 8 weeks in mild-to-moderate depression is very limited.

Recommendation. Advise patients to taper off St. John’s wort when stopping therapy to decrease the risk of withdrawal symptoms such as confusion, headache, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue.21 Given the high risk for drug interactions associated with St. John’s wort, we do not recommend its use in patients receiving any other medications.

KAVA KAVA AND LIVER TOXICITY

Kava kava (Piper methysticum) is used by some patients to treat anxiety and insomnia. Compared with other nutritional supplements, kava is less commonly used—by only 6.6% of adults using nutritional supplements,1—and it is not being evaluated in NIH-sponsored trials.

The active-ingredient content varies considerably in kava root, so extracts are standardized to contain 70% kava-lactones (WS 1490). Although its exact mechanism is unclear, kava appears to:

- alter the limbic system

- inhibit monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B)

- increase the number of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binding sites

- relax skeletal muscle

- produce anesthesia.24

Table 2

Documented interactions with St. John’s wort

| Alprazolam ↓ | Nevirapine ↓ |

| Amitriptyline ↓ | Oral contraceptives ↓ |

| Buspirone (ss) | Paroxetine (ss) |

| Cyclosporine ↓ | Sertraline (ss, mania) |

| Digoxin ↓ | Simvastatin ↓ |

| Fexofenadine ↓ | Tacrolimus ↓ |

| Indinavir ↓ | Theophylline ↓ |

| Irinotecan ↓ | Tyramine-containing |

| Methadone ↓ | foods (MAO-I reaction) |

| Midazolam ↓ | Venlafaxine (ss) |

| Nefazodone (ss) | Warfarin ↓ |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| ss = serotonin syndrome | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 21 | |

Table 3

Select potential interactions with St. John’s wort

| Cannabinoids ↓ | Fentanyl ↓ |

| Cocaine ↓ | Temazepam ↓ |

| Diazepam ↓ | Triazolam ↓ |

| Donepezil ↓ | |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 12 | |

Efficacy. A meta-analysis of studies found kava more effective than placebo in treating anxiety,25 although most studies suffer from poor design and/or small sample size.

Adverse effects. Reports have associated kava use with hepatic toxicity, liver failure requiring liver transplantation, and death. The European Union and Canada have banned kava sales, and the FDA issued a consumer advisory noting kava’s risks. Emerging information indicates that kava inhibits virtually all CYP-450 enzymes, which would increase levels of and potential adverse effects from any medications taken with kava.26

Other common adverse effects include GI upset, enlarged pupils, extrapyramidal side effects, and dizziness.24,27

Dosage. Kava is usually given at 100 mg (70 mg of kavalactones) three times daily. Urge patients to avoid driving when taking kava because of its side effects. Anxiety symptoms may improve with 1 to 8 weeks of therapy, but adverse hepatic effects can occur within 3 to 4 weeks of starting kava use.

Recommendation. Avoid kava kava use because of substantial risk of hepatotoxicity and drug interactions.

VALERIAN FOR INSOMNIA, ANXIETY

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) is promoted as a sedative/hypnotic and anxiolytic. The prevalence of valerian use (5.9%) mirrors that of kava.1 An NCCAM study is enrolling patients to evaluate valerian’s effectiveness in treating Parkinson’s disease-related sleep disturbances.

Efficacy. Information on valerian’s mechanism of action and clinical effectiveness is quite limited. In animal studies, its components produced direct sedative effects and inhibited CNS catabolism of GABA.28 Results are mixed in humans with insomnia; some studies have found reduced sleep latency and improved sleep quality with valerian use, whereas others found no improvements.29 Limited, small evaluations suggest that valerian may be useful in treating anxiety.

Adverse effects. The FDA categorizes valerian as an approved food additive, so it is considered safe in usual amounts found in food. FDA lists no amount that it considers safe in food, however, and the federal code covering valerian states that only enough needed to impart the desired flavor should be used.

When taken in therapeutic amounts, valerian’s most common adverse effects are headache and residual morning drowsiness. Because of the herb’s sedative effects, urge caution if patients drive while using it. On discontinuation, withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine withdrawal—anxiety, headache, emotional lability—have been reported.

Dosage. For insomnia, valerian is taken 2 hours to 30 minutes before bedtime; doses start at 300 to 400 mg and increase to 600 to 900 mg. Recommended doses vary, as standardization is less common with valerian than with other herbals. Continuous treatment seems more effective than as-needed dosing, as valerian may take up to 4 weeks to improve insomnia.

Recommendation. Well-controlled trials are lacking, and safety data at therapeutic doses are limited. Monitor patients using valerian for adverse effects and drug interactions.

- Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.www.naturaldatabase.com

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://nccam.nih.gov

- FDA MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. www.fda.gov/medwatch/how.htm

- ConsumerLab.com. Independent testing of dietary supplements. www.consumerlab.com

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amiodarone • Cordarone, Pacerone

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Cyclosporine • various

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Fentanyl • Duragesic

- Fexofenadine • Allegra

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Indinavir • Crixivan

- Irinotecan • Camptosar

- Methadone • various

- Midazolam • Versed

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nevirapine • Viramune

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Phenytoin • Dilantin

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Tacrolimus • Prograf

- Temazepam • Restoril

- Theophylline • various

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004.

2. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. Results of a follow-up survey. JAMA 1998;280:1569-75.

3. Matthews SC, Camacho A, Lawson K, Dimsdale JE. Use of herbal medications among 200 psychiatric outpatients: prevalence, patterns of use, and potential dangers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:24-6.

4. Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:61-9.

5. Grant KL. Patient education and herbal dietary supplements. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:1997-2003.

6. Harris IM. Regulatory and ethical issues with dietary supplements. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:1295-1302.

7. Sierpina VS, Wollschlaeger B, Blumenthal M. Ginkgo biloba. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:923-6.

8. LeBars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of ginkgo biloba for dementia. JAMA 1997;278:1327-32.

9. Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1998;55:1409-15.

10. Ginkgo biloba clinical trials National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/ginkgo.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

11. Gaudineau C, Beckerman R, Welbourn S, Auclair K. Inhibition of human P450 enzymes by multiple constituents of the ginkgo biloba extract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;318:1072-8.

12. Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P-450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy 1998;18:84-112.

13. Pepping J. St.John’s wort: hypericum perforatum. Am J HealthSyst Pharm 1999;56:329-30.

14. St John’s wort (hypericum) clinical trials. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/stjohnswort/index.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

15. Bennett DA, Phun L, Polk JF, et al. Neuropharmacology of St.John’s wort (hypericum). Ann Pharmacother 1998;32:1201-8.

16. Gaster B, Holroyd J. St.John’s wort for depression: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:152-6.

17. Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, et al. St.John’s wort for depression—an overview and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMJ 1996;313:253-8.

18. Shelton RC, Keller MB, Gelenberg A, et al. Effectiveness of St.John’s wort in major depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1978-86.

19. Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St.John’s wort) in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:1807-14.

20. Beckman SE, Sommi RW, Switzer J. Consumer use of St.John’s wort: a survey on effectiveness, safety, and tolerability. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:568-74.

21. Izzo AA. Drug interactions with St.John’s wort (hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42:139-48.

22. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St.John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA 2003;290:1500-4.

23. Sternbach H. Serotonin syndrome: how to avoid, identify, and treat dangerous drug reactions. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(5):14-24.

24. Pepping J. Kava: Piper methysticum. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 11999;56:957-60.

25. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:84-9.

26. Matthews JM, Etheridge AS, Black SR. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 activities by kava extract and kavalactones. Drug Metab Dispos 2002;30:1153-7.

27. Jellin JM, Gregory P, Batz F, et al. Kava Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database (3rd ed). Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Faculty, 2000;625:7.-

28. Hadley S, Petry JJ. Valerian. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1755-8.

29. Plushner SL. Valerian: Valeriana officinalis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:328-35.

What do you tell your patients who are self-medicating with herbal remedies? Can dietary supplements safely improve mood disorders, insomnia, and other psychiatric complaints?

Evidence is limited on complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), their active components, pharmacokinetics/dynamics, adverse effects, drug interactions, and therapeutic outcomes. Based on our review of trial data, case reports, and an NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) survey,1 we offer information to help you:

- identify patients using dietary supplements

- avoid serious interactions with common psychotropics

- counsel patients on the efficacy and safety of ginkgo biloba, St. John’s wort, kava kava, and valerian (Table 1).

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ASK

One-third of Americans who took part in the NCCAM survey reported using CAM. After prayer—the number-one CAM—respondents said they most often used natural products such as herbals, botanicals, nutraceuticals, phytomedicinals, and dietary supplements (Figure).1

Table 1

4 herbal supplements with purported psychotropic effects

| Herb | Promoted use | Safety | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba | Dementia, memory | Bleeding complications, drug interactions a concern | Some data support a trial in dementia; beware of safety concerns |

| St. John’s wort | Depression | Substantial drug interactions | Use not recommended because of wide-ranging drug interactions |

| Kava kava | Anxiety | Hepatotoxicity risk, drug interactions; off market in Europe and Canada | Use not recommended because of safety issues |

| Valerian | Insomnia | Limited data available | Benign (?); monitor for possible adverse events or drug interactions |

Patients tend to use CAM to treat chronic medical conditions such as back pain, depression, and anxiety.1 Although CAM use is common, only 38% of patients say they disclose using CAM to their physicians.2 These use and disclosure patterns are similar in psychiatry.3

Herbal products may produce symptoms that mimic those of mental illnesses, such as psychosis and mania, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Abruptly stopping some herbs can produce withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine and antidepressant cessation. Supplements also can inhibit or augment prescribed psychotropics’ effects, and notable consequences include the potential for serotonin syndrome with use of St. John’s wort.

The key to learning about a patient’s use of dietary supplements is to ask. Patients commonly say they do not tell their doctors about using dietary supplements because “it wasn’t important for the doctor to know” or “the doctor never asked.”4,5 Ten tips for discussing nutritional supplements with patients are shown in the Box.

Buyer—and psychiatrist—beware. Because of dietary supplements’ regulatory status, physicians and patients need to learn as much as they can about these products’ documented safety and efficacy. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act passed by Congress in 1994 does not require manufacturers to prove their products are safe or effective before marketing them. They also can make claims that suggest uses in physical/emotional structure and function, such as “helps maintain a healthy emotional outlook.”

The FDA bears the burden of proof regarding safety and can remove a dietary supplement from the market only after receiving documented adverse event information from the public.6 The FDA has confiscated herbal products containing prescription drugs and misidentified herbal components.

GINKGO BILOBA FOR DEMENTIA

Ginkgo biloba was the third most commonly used herbal product (21%) in the NCCAM survey. Ginkgo is promoted primarily for dementia, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and memory enhancement. The standardized ginkgo extract (EGb 761) contains several components to which its pharmacologic activity has been attributed. Its constituents are thought to act primarily through anticoagulant effects by inhibiting platelet-activating factor and cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. They also act through membrane stabilization, antioxidant properties, free-radical scavenging, and inhibition of beta-amyloid deposition.7

Efficacy. In patients with dementia, clinical trials using EGb 761 have shown small improvements in or maintenance of cognitive and social functioning, compared with placebo.8,9 The clinical significance of these findings is unclear, however. Ginkgo’s usefulness in enhancing memory is less certain. Controlled clinical trials are evaluating ginkgo’s efficacy in various conditions.10

Adverse effects. Bleeding complications are the primary concern with ginkgo biloba use, and caution is urged when it is taken concomitantly with aspirin or other antithrombotic drugs. Patients receiving warfarin should not take ginkgo because of the combined antiplatelet effects and ginkgo’s inhibition of warfarin metabolism and elimination.

Drug-herb interactions. One report showed that EGb 761 is a strong inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 2C9 enzyme system (CYP 2C9).11 Other identified inhibitors of CYP 2C9 are fluvoxamine (strong inhibitor), amiodarone, cimetidine, fluoxetine, and omeprazole. Drugs that serve as substrates for that system and can have decreased clearance include phenytoin, warfarin, amitriptyline, and diazepam;12 use caution, therefore, when you co-administer these drugs with ginkgo.

Figure 10 CAM therapies patients report using most often

CAM: Complimentary and alternative medicines

Source: Barnes T, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 27, 2004: Advance Data Report #343 (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad343.pdf) Dosage. The usual dosage for standardized ginkgo extract is 120 to 240 mg/d, given in divided doses. Improvements associated with ginkgo use usually are seen within 4 to 12 weeks after starting therapy.7 Consider discontinuing therapy if you see no results after that time. Little is known about ginkgo’s effect after 1 year of use.

Recommendation. Limited data show a slight benefit in treating dementia by slowing cognitive and behavioral decline, but ginkgo biloba cannot be recommended as a first-line treatment until further controlled trials are available.

- Broach the subject without being judgmental; nutritional supplement use is tied to a patient’s health beliefs

- Ask specifically about use of herbs, supplements, teas, elixirs, vitamins, etc., and document in the medical record at each visit

- Include in appointment reminders a request that patients bring all medicines, herbs, and supplements to appointments

- Segue into a discussion of supplements by noting their use by other patients with similar diagnoses

- Learn about and provide objective information on products

- Suggest use of single-ingredient products because:

- Suggest a symptom diary and a plan to discontinue a supplement if desired results are not seen

- Report suspected adverse events or drug interactions to the FDA

- Choose your battles carefully; testimonials and the placebo effect can strongly influence patients’ desire to continue using dietary supplements

- Remember: Patient safety is paramount

ST. JOHN’S WORT FOR DEPRESSION

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), used to treat mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety,13 is one of the most-recognized herbal remedies. It accounted for 12% of the natural products used in the NCCAM survey. Several clinical trials assessing St. John’s wort are in progress and include placebo-controlled evaluations in obsessive-compulsive disorder and social phobia.14

As with ginkgo, St. John’s wort has many proposed active constituents; most preparations are standardized based on a hypericin content of 0.3%. Its mechanism of action in depression is unclear but laboratory models hint that it may be related to very mild inhibition of:

- monoamine oxidase (MAO)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase(COMT)

- selective serotonin reuptake

- interleukin-6 release (thereby increasing corticotropin-releasing hormone levels)

- norepinephrine uptake.15

Efficacy. St. John’s wort has been studied in mild, moderate, and major depression and compared with placebo and prescription therapies. In treating mild and moderate depression, St. John’s wort has been more effective than placebo and equivalent to tricyclic antidepressants.16,17 Criticisms of these trials include lack of product standardization, lack of comparison with standard antidepressants at appropriate dosages, and small sample sizes. Larger trials comparing St. John’s wort with placebo and sertraline in treating major depression showed no difference in effect among the three.18,19

Adverse effects are generally infrequent and include insomnia, anxiety, GI upset, and photosensitivity reactions.20 St. John’s wort can induce hypomania and mania in patients with bipolar disorder and cause psychosis in schizophrenic patients.13

Drug-herb interactions. Of greatest concern with St. John’s wort use is the remarkable number of drug-herb interactions that have been identified (Table 2 and Table 3).13,21 The primary mechanisms appear to be substantial induction of CYP 3A4, induction of P-glycoprotein mediated drug elimination, and—to a lesser extent—induction of other CYP isoenzymes.22 Interactions resulting in serotonin syndrome have been documented, with restlessness, sweating, and agitation.23

The 3A4 isoenzyme metabolizes most drugs processed via the CYP system.12 Severe interactions seen with St. John’s wort include:

- reduced cyclosporine levels, resulting in heart transplant rejection in two patients

- reduced antiretroviral levels in HIV patients

- pregnancy in women taking oral contraceptives.

Enzyme induction may persist for as long as 14 days after patients stop taking St. John’s wort.

Dosage. The recommended St. John’s wort dosage (using standardized 0.3% hypericin content) is 300 mg 2 or 3 times daily. Dosages of 1,200 to 1,800 mg/d have been used.13,18 Benefits may not be seen for 2 to 3 weeks, and experience with use beyond 8 weeks in mild-to-moderate depression is very limited.

Recommendation. Advise patients to taper off St. John’s wort when stopping therapy to decrease the risk of withdrawal symptoms such as confusion, headache, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue.21 Given the high risk for drug interactions associated with St. John’s wort, we do not recommend its use in patients receiving any other medications.

KAVA KAVA AND LIVER TOXICITY

Kava kava (Piper methysticum) is used by some patients to treat anxiety and insomnia. Compared with other nutritional supplements, kava is less commonly used—by only 6.6% of adults using nutritional supplements,1—and it is not being evaluated in NIH-sponsored trials.

The active-ingredient content varies considerably in kava root, so extracts are standardized to contain 70% kava-lactones (WS 1490). Although its exact mechanism is unclear, kava appears to:

- alter the limbic system

- inhibit monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B)

- increase the number of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binding sites

- relax skeletal muscle

- produce anesthesia.24

Table 2

Documented interactions with St. John’s wort

| Alprazolam ↓ | Nevirapine ↓ |

| Amitriptyline ↓ | Oral contraceptives ↓ |

| Buspirone (ss) | Paroxetine (ss) |

| Cyclosporine ↓ | Sertraline (ss, mania) |

| Digoxin ↓ | Simvastatin ↓ |

| Fexofenadine ↓ | Tacrolimus ↓ |

| Indinavir ↓ | Theophylline ↓ |

| Irinotecan ↓ | Tyramine-containing |

| Methadone ↓ | foods (MAO-I reaction) |

| Midazolam ↓ | Venlafaxine (ss) |

| Nefazodone (ss) | Warfarin ↓ |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| ss = serotonin syndrome | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 21 | |

Table 3

Select potential interactions with St. John’s wort

| Cannabinoids ↓ | Fentanyl ↓ |

| Cocaine ↓ | Temazepam ↓ |

| Diazepam ↓ | Triazolam ↓ |

| Donepezil ↓ | |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 12 | |

Efficacy. A meta-analysis of studies found kava more effective than placebo in treating anxiety,25 although most studies suffer from poor design and/or small sample size.

Adverse effects. Reports have associated kava use with hepatic toxicity, liver failure requiring liver transplantation, and death. The European Union and Canada have banned kava sales, and the FDA issued a consumer advisory noting kava’s risks. Emerging information indicates that kava inhibits virtually all CYP-450 enzymes, which would increase levels of and potential adverse effects from any medications taken with kava.26

Other common adverse effects include GI upset, enlarged pupils, extrapyramidal side effects, and dizziness.24,27

Dosage. Kava is usually given at 100 mg (70 mg of kavalactones) three times daily. Urge patients to avoid driving when taking kava because of its side effects. Anxiety symptoms may improve with 1 to 8 weeks of therapy, but adverse hepatic effects can occur within 3 to 4 weeks of starting kava use.

Recommendation. Avoid kava kava use because of substantial risk of hepatotoxicity and drug interactions.

VALERIAN FOR INSOMNIA, ANXIETY

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) is promoted as a sedative/hypnotic and anxiolytic. The prevalence of valerian use (5.9%) mirrors that of kava.1 An NCCAM study is enrolling patients to evaluate valerian’s effectiveness in treating Parkinson’s disease-related sleep disturbances.

Efficacy. Information on valerian’s mechanism of action and clinical effectiveness is quite limited. In animal studies, its components produced direct sedative effects and inhibited CNS catabolism of GABA.28 Results are mixed in humans with insomnia; some studies have found reduced sleep latency and improved sleep quality with valerian use, whereas others found no improvements.29 Limited, small evaluations suggest that valerian may be useful in treating anxiety.

Adverse effects. The FDA categorizes valerian as an approved food additive, so it is considered safe in usual amounts found in food. FDA lists no amount that it considers safe in food, however, and the federal code covering valerian states that only enough needed to impart the desired flavor should be used.

When taken in therapeutic amounts, valerian’s most common adverse effects are headache and residual morning drowsiness. Because of the herb’s sedative effects, urge caution if patients drive while using it. On discontinuation, withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine withdrawal—anxiety, headache, emotional lability—have been reported.

Dosage. For insomnia, valerian is taken 2 hours to 30 minutes before bedtime; doses start at 300 to 400 mg and increase to 600 to 900 mg. Recommended doses vary, as standardization is less common with valerian than with other herbals. Continuous treatment seems more effective than as-needed dosing, as valerian may take up to 4 weeks to improve insomnia.

Recommendation. Well-controlled trials are lacking, and safety data at therapeutic doses are limited. Monitor patients using valerian for adverse effects and drug interactions.

- Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.www.naturaldatabase.com

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://nccam.nih.gov

- FDA MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. www.fda.gov/medwatch/how.htm

- ConsumerLab.com. Independent testing of dietary supplements. www.consumerlab.com

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amiodarone • Cordarone, Pacerone

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Cyclosporine • various

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Fentanyl • Duragesic

- Fexofenadine • Allegra

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Indinavir • Crixivan

- Irinotecan • Camptosar

- Methadone • various

- Midazolam • Versed

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nevirapine • Viramune

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Phenytoin • Dilantin

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Tacrolimus • Prograf

- Temazepam • Restoril

- Theophylline • various

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

What do you tell your patients who are self-medicating with herbal remedies? Can dietary supplements safely improve mood disorders, insomnia, and other psychiatric complaints?

Evidence is limited on complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), their active components, pharmacokinetics/dynamics, adverse effects, drug interactions, and therapeutic outcomes. Based on our review of trial data, case reports, and an NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) survey,1 we offer information to help you:

- identify patients using dietary supplements

- avoid serious interactions with common psychotropics

- counsel patients on the efficacy and safety of ginkgo biloba, St. John’s wort, kava kava, and valerian (Table 1).

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ASK

One-third of Americans who took part in the NCCAM survey reported using CAM. After prayer—the number-one CAM—respondents said they most often used natural products such as herbals, botanicals, nutraceuticals, phytomedicinals, and dietary supplements (Figure).1

Table 1

4 herbal supplements with purported psychotropic effects

| Herb | Promoted use | Safety | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba | Dementia, memory | Bleeding complications, drug interactions a concern | Some data support a trial in dementia; beware of safety concerns |

| St. John’s wort | Depression | Substantial drug interactions | Use not recommended because of wide-ranging drug interactions |

| Kava kava | Anxiety | Hepatotoxicity risk, drug interactions; off market in Europe and Canada | Use not recommended because of safety issues |

| Valerian | Insomnia | Limited data available | Benign (?); monitor for possible adverse events or drug interactions |

Patients tend to use CAM to treat chronic medical conditions such as back pain, depression, and anxiety.1 Although CAM use is common, only 38% of patients say they disclose using CAM to their physicians.2 These use and disclosure patterns are similar in psychiatry.3

Herbal products may produce symptoms that mimic those of mental illnesses, such as psychosis and mania, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Abruptly stopping some herbs can produce withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine and antidepressant cessation. Supplements also can inhibit or augment prescribed psychotropics’ effects, and notable consequences include the potential for serotonin syndrome with use of St. John’s wort.

The key to learning about a patient’s use of dietary supplements is to ask. Patients commonly say they do not tell their doctors about using dietary supplements because “it wasn’t important for the doctor to know” or “the doctor never asked.”4,5 Ten tips for discussing nutritional supplements with patients are shown in the Box.

Buyer—and psychiatrist—beware. Because of dietary supplements’ regulatory status, physicians and patients need to learn as much as they can about these products’ documented safety and efficacy. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act passed by Congress in 1994 does not require manufacturers to prove their products are safe or effective before marketing them. They also can make claims that suggest uses in physical/emotional structure and function, such as “helps maintain a healthy emotional outlook.”

The FDA bears the burden of proof regarding safety and can remove a dietary supplement from the market only after receiving documented adverse event information from the public.6 The FDA has confiscated herbal products containing prescription drugs and misidentified herbal components.

GINKGO BILOBA FOR DEMENTIA

Ginkgo biloba was the third most commonly used herbal product (21%) in the NCCAM survey. Ginkgo is promoted primarily for dementia, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and memory enhancement. The standardized ginkgo extract (EGb 761) contains several components to which its pharmacologic activity has been attributed. Its constituents are thought to act primarily through anticoagulant effects by inhibiting platelet-activating factor and cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. They also act through membrane stabilization, antioxidant properties, free-radical scavenging, and inhibition of beta-amyloid deposition.7

Efficacy. In patients with dementia, clinical trials using EGb 761 have shown small improvements in or maintenance of cognitive and social functioning, compared with placebo.8,9 The clinical significance of these findings is unclear, however. Ginkgo’s usefulness in enhancing memory is less certain. Controlled clinical trials are evaluating ginkgo’s efficacy in various conditions.10

Adverse effects. Bleeding complications are the primary concern with ginkgo biloba use, and caution is urged when it is taken concomitantly with aspirin or other antithrombotic drugs. Patients receiving warfarin should not take ginkgo because of the combined antiplatelet effects and ginkgo’s inhibition of warfarin metabolism and elimination.

Drug-herb interactions. One report showed that EGb 761 is a strong inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 2C9 enzyme system (CYP 2C9).11 Other identified inhibitors of CYP 2C9 are fluvoxamine (strong inhibitor), amiodarone, cimetidine, fluoxetine, and omeprazole. Drugs that serve as substrates for that system and can have decreased clearance include phenytoin, warfarin, amitriptyline, and diazepam;12 use caution, therefore, when you co-administer these drugs with ginkgo.

Figure 10 CAM therapies patients report using most often

CAM: Complimentary and alternative medicines

Source: Barnes T, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 27, 2004: Advance Data Report #343 (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad343.pdf) Dosage. The usual dosage for standardized ginkgo extract is 120 to 240 mg/d, given in divided doses. Improvements associated with ginkgo use usually are seen within 4 to 12 weeks after starting therapy.7 Consider discontinuing therapy if you see no results after that time. Little is known about ginkgo’s effect after 1 year of use.

Recommendation. Limited data show a slight benefit in treating dementia by slowing cognitive and behavioral decline, but ginkgo biloba cannot be recommended as a first-line treatment until further controlled trials are available.

- Broach the subject without being judgmental; nutritional supplement use is tied to a patient’s health beliefs

- Ask specifically about use of herbs, supplements, teas, elixirs, vitamins, etc., and document in the medical record at each visit

- Include in appointment reminders a request that patients bring all medicines, herbs, and supplements to appointments

- Segue into a discussion of supplements by noting their use by other patients with similar diagnoses

- Learn about and provide objective information on products

- Suggest use of single-ingredient products because:

- Suggest a symptom diary and a plan to discontinue a supplement if desired results are not seen

- Report suspected adverse events or drug interactions to the FDA

- Choose your battles carefully; testimonials and the placebo effect can strongly influence patients’ desire to continue using dietary supplements

- Remember: Patient safety is paramount

ST. JOHN’S WORT FOR DEPRESSION

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), used to treat mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety,13 is one of the most-recognized herbal remedies. It accounted for 12% of the natural products used in the NCCAM survey. Several clinical trials assessing St. John’s wort are in progress and include placebo-controlled evaluations in obsessive-compulsive disorder and social phobia.14

As with ginkgo, St. John’s wort has many proposed active constituents; most preparations are standardized based on a hypericin content of 0.3%. Its mechanism of action in depression is unclear but laboratory models hint that it may be related to very mild inhibition of:

- monoamine oxidase (MAO)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase(COMT)

- selective serotonin reuptake

- interleukin-6 release (thereby increasing corticotropin-releasing hormone levels)

- norepinephrine uptake.15

Efficacy. St. John’s wort has been studied in mild, moderate, and major depression and compared with placebo and prescription therapies. In treating mild and moderate depression, St. John’s wort has been more effective than placebo and equivalent to tricyclic antidepressants.16,17 Criticisms of these trials include lack of product standardization, lack of comparison with standard antidepressants at appropriate dosages, and small sample sizes. Larger trials comparing St. John’s wort with placebo and sertraline in treating major depression showed no difference in effect among the three.18,19

Adverse effects are generally infrequent and include insomnia, anxiety, GI upset, and photosensitivity reactions.20 St. John’s wort can induce hypomania and mania in patients with bipolar disorder and cause psychosis in schizophrenic patients.13

Drug-herb interactions. Of greatest concern with St. John’s wort use is the remarkable number of drug-herb interactions that have been identified (Table 2 and Table 3).13,21 The primary mechanisms appear to be substantial induction of CYP 3A4, induction of P-glycoprotein mediated drug elimination, and—to a lesser extent—induction of other CYP isoenzymes.22 Interactions resulting in serotonin syndrome have been documented, with restlessness, sweating, and agitation.23

The 3A4 isoenzyme metabolizes most drugs processed via the CYP system.12 Severe interactions seen with St. John’s wort include:

- reduced cyclosporine levels, resulting in heart transplant rejection in two patients

- reduced antiretroviral levels in HIV patients

- pregnancy in women taking oral contraceptives.

Enzyme induction may persist for as long as 14 days after patients stop taking St. John’s wort.

Dosage. The recommended St. John’s wort dosage (using standardized 0.3% hypericin content) is 300 mg 2 or 3 times daily. Dosages of 1,200 to 1,800 mg/d have been used.13,18 Benefits may not be seen for 2 to 3 weeks, and experience with use beyond 8 weeks in mild-to-moderate depression is very limited.

Recommendation. Advise patients to taper off St. John’s wort when stopping therapy to decrease the risk of withdrawal symptoms such as confusion, headache, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue.21 Given the high risk for drug interactions associated with St. John’s wort, we do not recommend its use in patients receiving any other medications.

KAVA KAVA AND LIVER TOXICITY

Kava kava (Piper methysticum) is used by some patients to treat anxiety and insomnia. Compared with other nutritional supplements, kava is less commonly used—by only 6.6% of adults using nutritional supplements,1—and it is not being evaluated in NIH-sponsored trials.

The active-ingredient content varies considerably in kava root, so extracts are standardized to contain 70% kava-lactones (WS 1490). Although its exact mechanism is unclear, kava appears to:

- alter the limbic system

- inhibit monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B)

- increase the number of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binding sites

- relax skeletal muscle

- produce anesthesia.24

Table 2

Documented interactions with St. John’s wort

| Alprazolam ↓ | Nevirapine ↓ |

| Amitriptyline ↓ | Oral contraceptives ↓ |

| Buspirone (ss) | Paroxetine (ss) |

| Cyclosporine ↓ | Sertraline (ss, mania) |

| Digoxin ↓ | Simvastatin ↓ |

| Fexofenadine ↓ | Tacrolimus ↓ |

| Indinavir ↓ | Theophylline ↓ |

| Irinotecan ↓ | Tyramine-containing |

| Methadone ↓ | foods (MAO-I reaction) |

| Midazolam ↓ | Venlafaxine (ss) |

| Nefazodone (ss) | Warfarin ↓ |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| ss = serotonin syndrome | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 21 | |

Table 3

Select potential interactions with St. John’s wort

| Cannabinoids ↓ | Fentanyl ↓ |

| Cocaine ↓ | Temazepam ↓ |

| Diazepam ↓ | Triazolam ↓ |

| Donepezil ↓ | |

| ↓= decreased levels/effectiveness | |

| Source: Adapted from reference 12 | |

Efficacy. A meta-analysis of studies found kava more effective than placebo in treating anxiety,25 although most studies suffer from poor design and/or small sample size.

Adverse effects. Reports have associated kava use with hepatic toxicity, liver failure requiring liver transplantation, and death. The European Union and Canada have banned kava sales, and the FDA issued a consumer advisory noting kava’s risks. Emerging information indicates that kava inhibits virtually all CYP-450 enzymes, which would increase levels of and potential adverse effects from any medications taken with kava.26

Other common adverse effects include GI upset, enlarged pupils, extrapyramidal side effects, and dizziness.24,27

Dosage. Kava is usually given at 100 mg (70 mg of kavalactones) three times daily. Urge patients to avoid driving when taking kava because of its side effects. Anxiety symptoms may improve with 1 to 8 weeks of therapy, but adverse hepatic effects can occur within 3 to 4 weeks of starting kava use.

Recommendation. Avoid kava kava use because of substantial risk of hepatotoxicity and drug interactions.

VALERIAN FOR INSOMNIA, ANXIETY

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) is promoted as a sedative/hypnotic and anxiolytic. The prevalence of valerian use (5.9%) mirrors that of kava.1 An NCCAM study is enrolling patients to evaluate valerian’s effectiveness in treating Parkinson’s disease-related sleep disturbances.

Efficacy. Information on valerian’s mechanism of action and clinical effectiveness is quite limited. In animal studies, its components produced direct sedative effects and inhibited CNS catabolism of GABA.28 Results are mixed in humans with insomnia; some studies have found reduced sleep latency and improved sleep quality with valerian use, whereas others found no improvements.29 Limited, small evaluations suggest that valerian may be useful in treating anxiety.

Adverse effects. The FDA categorizes valerian as an approved food additive, so it is considered safe in usual amounts found in food. FDA lists no amount that it considers safe in food, however, and the federal code covering valerian states that only enough needed to impart the desired flavor should be used.

When taken in therapeutic amounts, valerian’s most common adverse effects are headache and residual morning drowsiness. Because of the herb’s sedative effects, urge caution if patients drive while using it. On discontinuation, withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine withdrawal—anxiety, headache, emotional lability—have been reported.

Dosage. For insomnia, valerian is taken 2 hours to 30 minutes before bedtime; doses start at 300 to 400 mg and increase to 600 to 900 mg. Recommended doses vary, as standardization is less common with valerian than with other herbals. Continuous treatment seems more effective than as-needed dosing, as valerian may take up to 4 weeks to improve insomnia.

Recommendation. Well-controlled trials are lacking, and safety data at therapeutic doses are limited. Monitor patients using valerian for adverse effects and drug interactions.

- Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.www.naturaldatabase.com

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://nccam.nih.gov

- FDA MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. www.fda.gov/medwatch/how.htm

- ConsumerLab.com. Independent testing of dietary supplements. www.consumerlab.com

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amiodarone • Cordarone, Pacerone

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Cyclosporine • various

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Fentanyl • Duragesic

- Fexofenadine • Allegra

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Indinavir • Crixivan

- Irinotecan • Camptosar

- Methadone • various

- Midazolam • Versed

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nevirapine • Viramune

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Phenytoin • Dilantin

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Tacrolimus • Prograf

- Temazepam • Restoril

- Theophylline • various

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004.

2. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. Results of a follow-up survey. JAMA 1998;280:1569-75.

3. Matthews SC, Camacho A, Lawson K, Dimsdale JE. Use of herbal medications among 200 psychiatric outpatients: prevalence, patterns of use, and potential dangers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:24-6.

4. Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:61-9.

5. Grant KL. Patient education and herbal dietary supplements. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:1997-2003.

6. Harris IM. Regulatory and ethical issues with dietary supplements. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:1295-1302.

7. Sierpina VS, Wollschlaeger B, Blumenthal M. Ginkgo biloba. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:923-6.

8. LeBars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of ginkgo biloba for dementia. JAMA 1997;278:1327-32.

9. Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1998;55:1409-15.

10. Ginkgo biloba clinical trials National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/ginkgo.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

11. Gaudineau C, Beckerman R, Welbourn S, Auclair K. Inhibition of human P450 enzymes by multiple constituents of the ginkgo biloba extract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;318:1072-8.

12. Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P-450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy 1998;18:84-112.

13. Pepping J. St.John’s wort: hypericum perforatum. Am J HealthSyst Pharm 1999;56:329-30.

14. St John’s wort (hypericum) clinical trials. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/stjohnswort/index.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

15. Bennett DA, Phun L, Polk JF, et al. Neuropharmacology of St.John’s wort (hypericum). Ann Pharmacother 1998;32:1201-8.

16. Gaster B, Holroyd J. St.John’s wort for depression: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:152-6.

17. Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, et al. St.John’s wort for depression—an overview and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMJ 1996;313:253-8.

18. Shelton RC, Keller MB, Gelenberg A, et al. Effectiveness of St.John’s wort in major depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1978-86.

19. Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St.John’s wort) in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:1807-14.

20. Beckman SE, Sommi RW, Switzer J. Consumer use of St.John’s wort: a survey on effectiveness, safety, and tolerability. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:568-74.

21. Izzo AA. Drug interactions with St.John’s wort (hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42:139-48.

22. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St.John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA 2003;290:1500-4.

23. Sternbach H. Serotonin syndrome: how to avoid, identify, and treat dangerous drug reactions. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(5):14-24.

24. Pepping J. Kava: Piper methysticum. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 11999;56:957-60.

25. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:84-9.

26. Matthews JM, Etheridge AS, Black SR. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 activities by kava extract and kavalactones. Drug Metab Dispos 2002;30:1153-7.

27. Jellin JM, Gregory P, Batz F, et al. Kava Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database (3rd ed). Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Faculty, 2000;625:7.-

28. Hadley S, Petry JJ. Valerian. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1755-8.

29. Plushner SL. Valerian: Valeriana officinalis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:328-35.

1. Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004.

2. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. Results of a follow-up survey. JAMA 1998;280:1569-75.

3. Matthews SC, Camacho A, Lawson K, Dimsdale JE. Use of herbal medications among 200 psychiatric outpatients: prevalence, patterns of use, and potential dangers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:24-6.

4. Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:61-9.

5. Grant KL. Patient education and herbal dietary supplements. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:1997-2003.

6. Harris IM. Regulatory and ethical issues with dietary supplements. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:1295-1302.

7. Sierpina VS, Wollschlaeger B, Blumenthal M. Ginkgo biloba. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:923-6.

8. LeBars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of ginkgo biloba for dementia. JAMA 1997;278:1327-32.

9. Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1998;55:1409-15.

10. Ginkgo biloba clinical trials National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/ginkgo.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

11. Gaudineau C, Beckerman R, Welbourn S, Auclair K. Inhibition of human P450 enzymes by multiple constituents of the ginkgo biloba extract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;318:1072-8.

12. Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P-450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy 1998;18:84-112.

13. Pepping J. St.John’s wort: hypericum perforatum. Am J HealthSyst Pharm 1999;56:329-30.

14. St John’s wort (hypericum) clinical trials. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/stjohnswort/index.htm. Accessed Dec. 9, 2004.

15. Bennett DA, Phun L, Polk JF, et al. Neuropharmacology of St.John’s wort (hypericum). Ann Pharmacother 1998;32:1201-8.

16. Gaster B, Holroyd J. St.John’s wort for depression: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:152-6.

17. Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, et al. St.John’s wort for depression—an overview and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMJ 1996;313:253-8.

18. Shelton RC, Keller MB, Gelenberg A, et al. Effectiveness of St.John’s wort in major depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1978-86.

19. Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St.John’s wort) in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:1807-14.

20. Beckman SE, Sommi RW, Switzer J. Consumer use of St.John’s wort: a survey on effectiveness, safety, and tolerability. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:568-74.

21. Izzo AA. Drug interactions with St.John’s wort (hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42:139-48.

22. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St.John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA 2003;290:1500-4.

23. Sternbach H. Serotonin syndrome: how to avoid, identify, and treat dangerous drug reactions. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(5):14-24.

24. Pepping J. Kava: Piper methysticum. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 11999;56:957-60.

25. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:84-9.

26. Matthews JM, Etheridge AS, Black SR. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 activities by kava extract and kavalactones. Drug Metab Dispos 2002;30:1153-7.

27. Jellin JM, Gregory P, Batz F, et al. Kava Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database (3rd ed). Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Faculty, 2000;625:7.-

28. Hadley S, Petry JJ. Valerian. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1755-8.

29. Plushner SL. Valerian: Valeriana officinalis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2000;57:328-35.