User login

- The prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy has increased, due in part to in vitro fertilization techniques that transfer multiple embryos into the uterus.

- An interstitial eccyesis can be distinguished from an angular pregnancy by the anatomical relationships of the round and ovarian ligaments to the fallopian tube.

- Sonographic signs of interstitial heterotopic pregnancy include an eccentrically located echogenic mass surrounded by a thin myometrial rim, an interstitial line sign, and a myometrial bridge separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy.

- The choice of surgical or medical treatment of heterotopic pregnancy depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician.

- Physicians must closely observe during labor the hemodynamic status of women treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.

Heterotopic pregnancy is a condition on the rise. In 1948, just 1 in 30,000 gravidas presented with this disorder, in which uterine and extrauterine gestations exist concomitantly.1 Today that rate is 1 in 3,800.2 And for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), the number is a startling 1 in 100.3

Why such a dramatic shift? In the general population of women, the increase may be due in part to a rise in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),4 but other risk factors—including history of eccyesis, previous pelvic surgery, and congenital or acquired abnormalities of the uterine cavity—also may be contribute to the condition.3,5 But for IVF patients, the rise is largely attributable to the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus.2,6 In fact, when more than 5 embryos are implanted, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45.

When these rising incidence rates are coupled with the ever-increasing number of fertility treatments, it becomes clear that now it’s more important than ever that clinicians be able to readily recognize and treat this often-elusive condition.

Diagnosis

Heterotopic pregnancy is extremely difficult to diagnose. More than 50% of these pregnancies are identified by sonography or laparoscopy 2 weeks or more after the initial visualization of the intrauterine pregnancy,6 though approximately 85% go undiagnosed before the rupture of the eccyesis.

Typically, in women with suspected ectopic pregnancy, serial serum quantitative beta (ß) human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) tests are combined with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) to determine whether the pregnancy is intrauterine or extrauterine in nature. In distinguishing between ectopic and heterotopic pregnancies, however, serum ß-hCG determinations have not been particularly helpful, since each of the 2 pregnancies contribute to the total amount of circulating ß-hCG.5 In addition, up to 23% of heterotopic pregnancies have hCG levels comparable to singleton intrauterine pregnancies.5

Treatment of an eccyesis must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy.

The assumption that detecting an intrauterine gestational sac by TVUS excludes eccyesis is based on the 50-year-old estimate of the prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy (1 in 30,000). In fact, TVUS has been quite useful in the early detection of heterotopic pregnancy. The sonographic finding of 1 gestational sac in the uterine cavity with another in the adnexum is diagnostic of this condition.

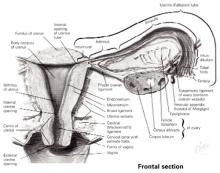

Approximately 90% of eccyesis accompanying intrauterine pregnancy occur in the fallopian tube, usually within its ampulla (FIGURE 1). It is perhaps easier to diagnose an ampullary pregnancy than an interstitial pregnancy, because there is a greater index of suspicion with a tube in place. However, an ampullary pregnancy also may be missed unless a heartbeat is detected in the adnexum.

Unfortunately, for women with heterotopic pregnancy who have undergone salpingectomy and whose eccyesis resides in the interstitial or cornual remnants of the fallopian tube—a condition that occurs in 4% of heterotopic pregnancies7—an ultrasonic mass adjacent to the uterus is unlikely to raise suspicion of an eccyesis. This is because the adjacent intrauterine gestational sac mimics a singleton intrauterine pregnancy. (Few eccyesis occur in the ovary, cervix, or abdomen.6) But failure to diagnose an interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy increases a woman’s risk of intraabdominal hemorrhage, as rupture of the thickened, vascular muscularis surrounding the eccyesis is delayed for up to 16 gestational weeks.

The sonographic signs suggestive of an interstitial eccyesis include a chorionic sac, or echogenic mass, located approximately 1 cm lateral to the uterine cavity and surrounded by a thin myometrial rim (less than 5 mm). In addition, an interstitial line sign—defined as an echogenic line extending through the cornual region and into the middle of the interstitial mass—is 92% sensitive and nearly 100% specific for diagnosing an interstitial pregnancy.6,8 Color Doppler sonography may detect a “ring of fire” from high-velocity or low-impedance blood flow surrounding an eccyesis (separate from a corpus luteum). A resistance index of less than 0.40 for such a mass (outside the ovary) is suspicious of an extrauterine pregnancy.9 Plus, an 8% difference in the resistance index between tubal arteries is 86% sensitive and 96% specific for eccyesis.10 In addition to these findings, a TVUS showing a bridge of myometrium separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy strongly suggests a heterotopic pregnancy.6,11

An interstitial or cornual pregnancy discovered at surgery may be difficult to distinguish from an angular pregnancy, i.e., an intrauterine pregnancy that implants in the lateral angle of the uterine cavity. The distinction is crucial, however, because an angular pregnancy is more likely to miscarry (38%) than to rupture.6 The angular pregnancies that do not miscarry are more likely to involve preterm labor. Interstitial eccyesis is surgically diagnosed by a hemorrhagic swelling in the uterine cornua that either displaces the round ligament anteriorly or the ovarian ligament posteriorly, depending upon whether it erodes through the anterior or posterior walls of the tube, respectively (FIGURES 2 and 3).7 An angular pregnancy appears as a similar cornual swelling, but does not distort the anatomical relationships between the round or ovarian ligaments and the fallopian tube.

FIGURE 1 Anatomy of the fallopian tube

Copyright 1989. Icon Learning Systems, LLC, a subsidiary of MediMedia USA Inc. Reprinted with permission from Icon Learning Systems, LLC, illustrated by Frank H. Netter, MD. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 2 Angular versus interstitial or cornual pregnancy

Reprinted with permission from Kadar N. Diagnosis and treatment of extrauterine pregnancies. New York: Raven Press; 1990:148.

FIGURE 3 Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy

Intraoperative photograph of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy, with rupture of its interstitial gestation through the left salpingectomy site (located between sutures). The interstitial pregnancy is easily distinguished from an angular pregnancy by its lateral location to the ipsilateral round ligament (held in background by far babcock clamp).

Reprinted with permission from Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

Treatment

Any treatment of an eccyesis in a heterotopic pregnancy must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy. The choice of surgical or medical treatment depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician. Surgical therapy is optimal when the patient is in shock and the physician has appropriate surgical training.

Surgical. While prospective randomized trials of surgical versus medical strategies do not exist, laparoscopy is ideally suited to remove an unruptured eccyesis without disrupting the remaining intrauterine pregnancy. When the eccyesis ruptures, the intrauterine gestation still can survive. But decreased perfusion to the normal pregnancy places it at theoretical risk for miscarriage.

Laparoscopy should be performed without the use of an intracervical uterine manipulator, with the Veress needle inserted carefully into the abdomen to avoid perforating the gravid uterus. After abdominal insufflation, the choice of laparoscopic salpingectomy or cornual resection depends on the location of the eccyesis within the fallopian tube or its remnant. Generally, physicians should perform a salpingectomy for ampullary pregnancies and a cornual resection for cornual pregnancies. Regardless of the surgical approach, the use of sutures3 or staples12—rather than electrocautery or intramyometrial injection of vasopressin—minimizes the risk of diminishing blood flow to the surviving intrauterine pregnancy, particularly during cornual resection. Exploratory laparotomy is appropriate when a ruptured eccyesis is associated with severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Medical. Therapeutic treatments for heterotopic pregnancy include transvaginal injection of the unruptured eccyesis with potassium chloride,13 potassium chloride with methotrexate,14 or hyperosmolar glucose.15 While clinical experience in treating heterotopic pregnancy is limited, transvaginal injection of methotrexate into an eccyesis could potentially harm the adjacent intrauterine pregnancy.16 Under similar circumstances, the use of potassium chloride has been shown at the time of cesarean section to distort the cornua, suggesting longterm impairment of tubal function.11

In general, we favor the surgical therapies described above, because they can be performed quickly under outpatient conditions while eliminating the risk of later ectopic rupture. Medical therapy is best performed when the patient is clinically stable, compliant, and willing to be monitored over time in the clinic. When such a patient has restricted surgical access to the pelvis due to adhesions, we prefer administering a transvaginal injection of potassium chloride.

Final thoughts

It is important to note that one-third of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy miscarry in the first (89%) and second trimesters (8.5%). Miscarriage beyond the second trimester is rare, though preterm delivery may occur—particularly when heterotopic pregnancy is accompanied by multiple births. Still, a full two-thirds of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy do survive to term.

Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment and delivery. Ultrasonographers must methodically examine the entire pelvic region, particularly in women who have had pelvic surgery, PID, or who are conceiving after a workup for fertility. Once a woman has been treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, close observation of the patient’s hemodynamic status during labor is recommended, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.3

The authors report no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

1. Devoe WD, Pratt JH. Simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy. AJOG. 1948;56(6):1119-1126.

2. Habana A, Dokras A, Giraldo JL, Jones EE. Cornual heterotopic pregnancy: contemporary management options. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1264-1270.

3. Lau S, Tunlandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(2):207-215.

4. Rock JA, Thompson JD. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:504.

5. Wang PH, Chao HT, Tseng JY, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for heterotopic pregnancies: a case report and a brief review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1998;80:267-271.

6. Tal J, Haddad S, Gordon N, Timor-Tritsch I. Heterotopic pregnancy after ovulation induction and assisted reproductive technologies: a literature review from 1971 to 1993. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(1):1-12.

7. Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

8. Ackerman TE, Levi CS, Dashefsky SM, Holt SC, Lindsay DJ. Interstitial line: sonographic finding in interstitial (cornual) ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 1993;189:83-87.

9. Vourtsi A, Antoniou A, Stefanopoulos T, Kapetanakis E, Vlahos L. Endovaginal color Doppler sonographic evaluation of ectopic pregnancy in women after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Eur Radiology. 1999;9:1208-1213.

10. Zullo F, Pellicano M, Di Carlo C, et al. Heterotopic pregnancy in a woman without previous ovarian hyperstimulation: ultrasound diagnosis and management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1996;66:193-195.

11. Leach RE, Ney JA, Ory SJ. Selective embryo reduction of an interstitial heterotopic gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1992;7:41-45.

12. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1):216-217.

13. Perez JA, Sadek MM, Savale M, Boyer P, Zorn JR. Local medical treatment of interstitial pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET): two case reports. Hum Reprod. 1993;8(4):631-634.

14. Baker VL, Givens CR, Cadieux MCM. Transvaginal reduction of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy with preservation of the intrauterine gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):1384-1385.

15. Strohmer H, Obruca A, Lehner R, Egarter C, Husslein P, Feichtinger W. Successful treatment of a heterotopic pregnancy by sonographicallly guided instillation of hyperosmolar glucose. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(1):149-151.

16. Fernandez H, Bourget P, Ville Y, Lelaidier C, Frydman R. Treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy with methotrexate: pharmacokinetic analysis of local versus intramuscular administration. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:943-947.

- The prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy has increased, due in part to in vitro fertilization techniques that transfer multiple embryos into the uterus.

- An interstitial eccyesis can be distinguished from an angular pregnancy by the anatomical relationships of the round and ovarian ligaments to the fallopian tube.

- Sonographic signs of interstitial heterotopic pregnancy include an eccentrically located echogenic mass surrounded by a thin myometrial rim, an interstitial line sign, and a myometrial bridge separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy.

- The choice of surgical or medical treatment of heterotopic pregnancy depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician.

- Physicians must closely observe during labor the hemodynamic status of women treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.

Heterotopic pregnancy is a condition on the rise. In 1948, just 1 in 30,000 gravidas presented with this disorder, in which uterine and extrauterine gestations exist concomitantly.1 Today that rate is 1 in 3,800.2 And for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), the number is a startling 1 in 100.3

Why such a dramatic shift? In the general population of women, the increase may be due in part to a rise in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),4 but other risk factors—including history of eccyesis, previous pelvic surgery, and congenital or acquired abnormalities of the uterine cavity—also may be contribute to the condition.3,5 But for IVF patients, the rise is largely attributable to the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus.2,6 In fact, when more than 5 embryos are implanted, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45.

When these rising incidence rates are coupled with the ever-increasing number of fertility treatments, it becomes clear that now it’s more important than ever that clinicians be able to readily recognize and treat this often-elusive condition.

Diagnosis

Heterotopic pregnancy is extremely difficult to diagnose. More than 50% of these pregnancies are identified by sonography or laparoscopy 2 weeks or more after the initial visualization of the intrauterine pregnancy,6 though approximately 85% go undiagnosed before the rupture of the eccyesis.

Typically, in women with suspected ectopic pregnancy, serial serum quantitative beta (ß) human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) tests are combined with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) to determine whether the pregnancy is intrauterine or extrauterine in nature. In distinguishing between ectopic and heterotopic pregnancies, however, serum ß-hCG determinations have not been particularly helpful, since each of the 2 pregnancies contribute to the total amount of circulating ß-hCG.5 In addition, up to 23% of heterotopic pregnancies have hCG levels comparable to singleton intrauterine pregnancies.5

Treatment of an eccyesis must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy.

The assumption that detecting an intrauterine gestational sac by TVUS excludes eccyesis is based on the 50-year-old estimate of the prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy (1 in 30,000). In fact, TVUS has been quite useful in the early detection of heterotopic pregnancy. The sonographic finding of 1 gestational sac in the uterine cavity with another in the adnexum is diagnostic of this condition.

Approximately 90% of eccyesis accompanying intrauterine pregnancy occur in the fallopian tube, usually within its ampulla (FIGURE 1). It is perhaps easier to diagnose an ampullary pregnancy than an interstitial pregnancy, because there is a greater index of suspicion with a tube in place. However, an ampullary pregnancy also may be missed unless a heartbeat is detected in the adnexum.

Unfortunately, for women with heterotopic pregnancy who have undergone salpingectomy and whose eccyesis resides in the interstitial or cornual remnants of the fallopian tube—a condition that occurs in 4% of heterotopic pregnancies7—an ultrasonic mass adjacent to the uterus is unlikely to raise suspicion of an eccyesis. This is because the adjacent intrauterine gestational sac mimics a singleton intrauterine pregnancy. (Few eccyesis occur in the ovary, cervix, or abdomen.6) But failure to diagnose an interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy increases a woman’s risk of intraabdominal hemorrhage, as rupture of the thickened, vascular muscularis surrounding the eccyesis is delayed for up to 16 gestational weeks.

The sonographic signs suggestive of an interstitial eccyesis include a chorionic sac, or echogenic mass, located approximately 1 cm lateral to the uterine cavity and surrounded by a thin myometrial rim (less than 5 mm). In addition, an interstitial line sign—defined as an echogenic line extending through the cornual region and into the middle of the interstitial mass—is 92% sensitive and nearly 100% specific for diagnosing an interstitial pregnancy.6,8 Color Doppler sonography may detect a “ring of fire” from high-velocity or low-impedance blood flow surrounding an eccyesis (separate from a corpus luteum). A resistance index of less than 0.40 for such a mass (outside the ovary) is suspicious of an extrauterine pregnancy.9 Plus, an 8% difference in the resistance index between tubal arteries is 86% sensitive and 96% specific for eccyesis.10 In addition to these findings, a TVUS showing a bridge of myometrium separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy strongly suggests a heterotopic pregnancy.6,11

An interstitial or cornual pregnancy discovered at surgery may be difficult to distinguish from an angular pregnancy, i.e., an intrauterine pregnancy that implants in the lateral angle of the uterine cavity. The distinction is crucial, however, because an angular pregnancy is more likely to miscarry (38%) than to rupture.6 The angular pregnancies that do not miscarry are more likely to involve preterm labor. Interstitial eccyesis is surgically diagnosed by a hemorrhagic swelling in the uterine cornua that either displaces the round ligament anteriorly or the ovarian ligament posteriorly, depending upon whether it erodes through the anterior or posterior walls of the tube, respectively (FIGURES 2 and 3).7 An angular pregnancy appears as a similar cornual swelling, but does not distort the anatomical relationships between the round or ovarian ligaments and the fallopian tube.

FIGURE 1 Anatomy of the fallopian tube

Copyright 1989. Icon Learning Systems, LLC, a subsidiary of MediMedia USA Inc. Reprinted with permission from Icon Learning Systems, LLC, illustrated by Frank H. Netter, MD. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 2 Angular versus interstitial or cornual pregnancy

Reprinted with permission from Kadar N. Diagnosis and treatment of extrauterine pregnancies. New York: Raven Press; 1990:148.

FIGURE 3 Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy

Intraoperative photograph of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy, with rupture of its interstitial gestation through the left salpingectomy site (located between sutures). The interstitial pregnancy is easily distinguished from an angular pregnancy by its lateral location to the ipsilateral round ligament (held in background by far babcock clamp).

Reprinted with permission from Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

Treatment

Any treatment of an eccyesis in a heterotopic pregnancy must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy. The choice of surgical or medical treatment depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician. Surgical therapy is optimal when the patient is in shock and the physician has appropriate surgical training.

Surgical. While prospective randomized trials of surgical versus medical strategies do not exist, laparoscopy is ideally suited to remove an unruptured eccyesis without disrupting the remaining intrauterine pregnancy. When the eccyesis ruptures, the intrauterine gestation still can survive. But decreased perfusion to the normal pregnancy places it at theoretical risk for miscarriage.

Laparoscopy should be performed without the use of an intracervical uterine manipulator, with the Veress needle inserted carefully into the abdomen to avoid perforating the gravid uterus. After abdominal insufflation, the choice of laparoscopic salpingectomy or cornual resection depends on the location of the eccyesis within the fallopian tube or its remnant. Generally, physicians should perform a salpingectomy for ampullary pregnancies and a cornual resection for cornual pregnancies. Regardless of the surgical approach, the use of sutures3 or staples12—rather than electrocautery or intramyometrial injection of vasopressin—minimizes the risk of diminishing blood flow to the surviving intrauterine pregnancy, particularly during cornual resection. Exploratory laparotomy is appropriate when a ruptured eccyesis is associated with severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Medical. Therapeutic treatments for heterotopic pregnancy include transvaginal injection of the unruptured eccyesis with potassium chloride,13 potassium chloride with methotrexate,14 or hyperosmolar glucose.15 While clinical experience in treating heterotopic pregnancy is limited, transvaginal injection of methotrexate into an eccyesis could potentially harm the adjacent intrauterine pregnancy.16 Under similar circumstances, the use of potassium chloride has been shown at the time of cesarean section to distort the cornua, suggesting longterm impairment of tubal function.11

In general, we favor the surgical therapies described above, because they can be performed quickly under outpatient conditions while eliminating the risk of later ectopic rupture. Medical therapy is best performed when the patient is clinically stable, compliant, and willing to be monitored over time in the clinic. When such a patient has restricted surgical access to the pelvis due to adhesions, we prefer administering a transvaginal injection of potassium chloride.

Final thoughts

It is important to note that one-third of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy miscarry in the first (89%) and second trimesters (8.5%). Miscarriage beyond the second trimester is rare, though preterm delivery may occur—particularly when heterotopic pregnancy is accompanied by multiple births. Still, a full two-thirds of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy do survive to term.

Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment and delivery. Ultrasonographers must methodically examine the entire pelvic region, particularly in women who have had pelvic surgery, PID, or who are conceiving after a workup for fertility. Once a woman has been treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, close observation of the patient’s hemodynamic status during labor is recommended, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.3

The authors report no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

- The prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy has increased, due in part to in vitro fertilization techniques that transfer multiple embryos into the uterus.

- An interstitial eccyesis can be distinguished from an angular pregnancy by the anatomical relationships of the round and ovarian ligaments to the fallopian tube.

- Sonographic signs of interstitial heterotopic pregnancy include an eccentrically located echogenic mass surrounded by a thin myometrial rim, an interstitial line sign, and a myometrial bridge separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy.

- The choice of surgical or medical treatment of heterotopic pregnancy depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician.

- Physicians must closely observe during labor the hemodynamic status of women treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.

Heterotopic pregnancy is a condition on the rise. In 1948, just 1 in 30,000 gravidas presented with this disorder, in which uterine and extrauterine gestations exist concomitantly.1 Today that rate is 1 in 3,800.2 And for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), the number is a startling 1 in 100.3

Why such a dramatic shift? In the general population of women, the increase may be due in part to a rise in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),4 but other risk factors—including history of eccyesis, previous pelvic surgery, and congenital or acquired abnormalities of the uterine cavity—also may be contribute to the condition.3,5 But for IVF patients, the rise is largely attributable to the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus.2,6 In fact, when more than 5 embryos are implanted, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45.

When these rising incidence rates are coupled with the ever-increasing number of fertility treatments, it becomes clear that now it’s more important than ever that clinicians be able to readily recognize and treat this often-elusive condition.

Diagnosis

Heterotopic pregnancy is extremely difficult to diagnose. More than 50% of these pregnancies are identified by sonography or laparoscopy 2 weeks or more after the initial visualization of the intrauterine pregnancy,6 though approximately 85% go undiagnosed before the rupture of the eccyesis.

Typically, in women with suspected ectopic pregnancy, serial serum quantitative beta (ß) human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) tests are combined with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) to determine whether the pregnancy is intrauterine or extrauterine in nature. In distinguishing between ectopic and heterotopic pregnancies, however, serum ß-hCG determinations have not been particularly helpful, since each of the 2 pregnancies contribute to the total amount of circulating ß-hCG.5 In addition, up to 23% of heterotopic pregnancies have hCG levels comparable to singleton intrauterine pregnancies.5

Treatment of an eccyesis must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy.

The assumption that detecting an intrauterine gestational sac by TVUS excludes eccyesis is based on the 50-year-old estimate of the prevalence of heterotopic pregnancy (1 in 30,000). In fact, TVUS has been quite useful in the early detection of heterotopic pregnancy. The sonographic finding of 1 gestational sac in the uterine cavity with another in the adnexum is diagnostic of this condition.

Approximately 90% of eccyesis accompanying intrauterine pregnancy occur in the fallopian tube, usually within its ampulla (FIGURE 1). It is perhaps easier to diagnose an ampullary pregnancy than an interstitial pregnancy, because there is a greater index of suspicion with a tube in place. However, an ampullary pregnancy also may be missed unless a heartbeat is detected in the adnexum.

Unfortunately, for women with heterotopic pregnancy who have undergone salpingectomy and whose eccyesis resides in the interstitial or cornual remnants of the fallopian tube—a condition that occurs in 4% of heterotopic pregnancies7—an ultrasonic mass adjacent to the uterus is unlikely to raise suspicion of an eccyesis. This is because the adjacent intrauterine gestational sac mimics a singleton intrauterine pregnancy. (Few eccyesis occur in the ovary, cervix, or abdomen.6) But failure to diagnose an interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy increases a woman’s risk of intraabdominal hemorrhage, as rupture of the thickened, vascular muscularis surrounding the eccyesis is delayed for up to 16 gestational weeks.

The sonographic signs suggestive of an interstitial eccyesis include a chorionic sac, or echogenic mass, located approximately 1 cm lateral to the uterine cavity and surrounded by a thin myometrial rim (less than 5 mm). In addition, an interstitial line sign—defined as an echogenic line extending through the cornual region and into the middle of the interstitial mass—is 92% sensitive and nearly 100% specific for diagnosing an interstitial pregnancy.6,8 Color Doppler sonography may detect a “ring of fire” from high-velocity or low-impedance blood flow surrounding an eccyesis (separate from a corpus luteum). A resistance index of less than 0.40 for such a mass (outside the ovary) is suspicious of an extrauterine pregnancy.9 Plus, an 8% difference in the resistance index between tubal arteries is 86% sensitive and 96% specific for eccyesis.10 In addition to these findings, a TVUS showing a bridge of myometrium separating a suspected eccyesis from an intrauterine pregnancy strongly suggests a heterotopic pregnancy.6,11

An interstitial or cornual pregnancy discovered at surgery may be difficult to distinguish from an angular pregnancy, i.e., an intrauterine pregnancy that implants in the lateral angle of the uterine cavity. The distinction is crucial, however, because an angular pregnancy is more likely to miscarry (38%) than to rupture.6 The angular pregnancies that do not miscarry are more likely to involve preterm labor. Interstitial eccyesis is surgically diagnosed by a hemorrhagic swelling in the uterine cornua that either displaces the round ligament anteriorly or the ovarian ligament posteriorly, depending upon whether it erodes through the anterior or posterior walls of the tube, respectively (FIGURES 2 and 3).7 An angular pregnancy appears as a similar cornual swelling, but does not distort the anatomical relationships between the round or ovarian ligaments and the fallopian tube.

FIGURE 1 Anatomy of the fallopian tube

Copyright 1989. Icon Learning Systems, LLC, a subsidiary of MediMedia USA Inc. Reprinted with permission from Icon Learning Systems, LLC, illustrated by Frank H. Netter, MD. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 2 Angular versus interstitial or cornual pregnancy

Reprinted with permission from Kadar N. Diagnosis and treatment of extrauterine pregnancies. New York: Raven Press; 1990:148.

FIGURE 3 Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy

Intraoperative photograph of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy, with rupture of its interstitial gestation through the left salpingectomy site (located between sutures). The interstitial pregnancy is easily distinguished from an angular pregnancy by its lateral location to the ipsilateral round ligament (held in background by far babcock clamp).

Reprinted with permission from Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

Treatment

Any treatment of an eccyesis in a heterotopic pregnancy must consider the viability of the intrauterine pregnancy. The choice of surgical or medical treatment depends upon the hemodynamic status of the patient and the expertise of the physician. Surgical therapy is optimal when the patient is in shock and the physician has appropriate surgical training.

Surgical. While prospective randomized trials of surgical versus medical strategies do not exist, laparoscopy is ideally suited to remove an unruptured eccyesis without disrupting the remaining intrauterine pregnancy. When the eccyesis ruptures, the intrauterine gestation still can survive. But decreased perfusion to the normal pregnancy places it at theoretical risk for miscarriage.

Laparoscopy should be performed without the use of an intracervical uterine manipulator, with the Veress needle inserted carefully into the abdomen to avoid perforating the gravid uterus. After abdominal insufflation, the choice of laparoscopic salpingectomy or cornual resection depends on the location of the eccyesis within the fallopian tube or its remnant. Generally, physicians should perform a salpingectomy for ampullary pregnancies and a cornual resection for cornual pregnancies. Regardless of the surgical approach, the use of sutures3 or staples12—rather than electrocautery or intramyometrial injection of vasopressin—minimizes the risk of diminishing blood flow to the surviving intrauterine pregnancy, particularly during cornual resection. Exploratory laparotomy is appropriate when a ruptured eccyesis is associated with severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Medical. Therapeutic treatments for heterotopic pregnancy include transvaginal injection of the unruptured eccyesis with potassium chloride,13 potassium chloride with methotrexate,14 or hyperosmolar glucose.15 While clinical experience in treating heterotopic pregnancy is limited, transvaginal injection of methotrexate into an eccyesis could potentially harm the adjacent intrauterine pregnancy.16 Under similar circumstances, the use of potassium chloride has been shown at the time of cesarean section to distort the cornua, suggesting longterm impairment of tubal function.11

In general, we favor the surgical therapies described above, because they can be performed quickly under outpatient conditions while eliminating the risk of later ectopic rupture. Medical therapy is best performed when the patient is clinically stable, compliant, and willing to be monitored over time in the clinic. When such a patient has restricted surgical access to the pelvis due to adhesions, we prefer administering a transvaginal injection of potassium chloride.

Final thoughts

It is important to note that one-third of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy miscarry in the first (89%) and second trimesters (8.5%). Miscarriage beyond the second trimester is rare, though preterm delivery may occur—particularly when heterotopic pregnancy is accompanied by multiple births. Still, a full two-thirds of intrauterine pregnancies accompanying heterotopic pregnancy do survive to term.

Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment and delivery. Ultrasonographers must methodically examine the entire pelvic region, particularly in women who have had pelvic surgery, PID, or who are conceiving after a workup for fertility. Once a woman has been treated for interstitial or cornual heterotopic pregnancy, close observation of the patient’s hemodynamic status during labor is recommended, since the risk of uterine rupture is unknown.3

The authors report no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

1. Devoe WD, Pratt JH. Simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy. AJOG. 1948;56(6):1119-1126.

2. Habana A, Dokras A, Giraldo JL, Jones EE. Cornual heterotopic pregnancy: contemporary management options. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1264-1270.

3. Lau S, Tunlandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(2):207-215.

4. Rock JA, Thompson JD. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:504.

5. Wang PH, Chao HT, Tseng JY, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for heterotopic pregnancies: a case report and a brief review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1998;80:267-271.

6. Tal J, Haddad S, Gordon N, Timor-Tritsch I. Heterotopic pregnancy after ovulation induction and assisted reproductive technologies: a literature review from 1971 to 1993. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(1):1-12.

7. Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

8. Ackerman TE, Levi CS, Dashefsky SM, Holt SC, Lindsay DJ. Interstitial line: sonographic finding in interstitial (cornual) ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 1993;189:83-87.

9. Vourtsi A, Antoniou A, Stefanopoulos T, Kapetanakis E, Vlahos L. Endovaginal color Doppler sonographic evaluation of ectopic pregnancy in women after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Eur Radiology. 1999;9:1208-1213.

10. Zullo F, Pellicano M, Di Carlo C, et al. Heterotopic pregnancy in a woman without previous ovarian hyperstimulation: ultrasound diagnosis and management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1996;66:193-195.

11. Leach RE, Ney JA, Ory SJ. Selective embryo reduction of an interstitial heterotopic gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1992;7:41-45.

12. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1):216-217.

13. Perez JA, Sadek MM, Savale M, Boyer P, Zorn JR. Local medical treatment of interstitial pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET): two case reports. Hum Reprod. 1993;8(4):631-634.

14. Baker VL, Givens CR, Cadieux MCM. Transvaginal reduction of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy with preservation of the intrauterine gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):1384-1385.

15. Strohmer H, Obruca A, Lehner R, Egarter C, Husslein P, Feichtinger W. Successful treatment of a heterotopic pregnancy by sonographicallly guided instillation of hyperosmolar glucose. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(1):149-151.

16. Fernandez H, Bourget P, Ville Y, Lelaidier C, Frydman R. Treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy with methotrexate: pharmacokinetic analysis of local versus intramuscular administration. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:943-947.

1. Devoe WD, Pratt JH. Simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy. AJOG. 1948;56(6):1119-1126.

2. Habana A, Dokras A, Giraldo JL, Jones EE. Cornual heterotopic pregnancy: contemporary management options. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1264-1270.

3. Lau S, Tunlandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(2):207-215.

4. Rock JA, Thompson JD. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:504.

5. Wang PH, Chao HT, Tseng JY, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for heterotopic pregnancies: a case report and a brief review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1998;80:267-271.

6. Tal J, Haddad S, Gordon N, Timor-Tritsch I. Heterotopic pregnancy after ovulation induction and assisted reproductive technologies: a literature review from 1971 to 1993. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(1):1-12.

7. Dumesic DA, Damario MA, Session DR. Interstitial heterotopic pregnancy in a woman conceiving by in vitro fertilization after bilateral salpingectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:90-92.

8. Ackerman TE, Levi CS, Dashefsky SM, Holt SC, Lindsay DJ. Interstitial line: sonographic finding in interstitial (cornual) ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 1993;189:83-87.

9. Vourtsi A, Antoniou A, Stefanopoulos T, Kapetanakis E, Vlahos L. Endovaginal color Doppler sonographic evaluation of ectopic pregnancy in women after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Eur Radiology. 1999;9:1208-1213.

10. Zullo F, Pellicano M, Di Carlo C, et al. Heterotopic pregnancy in a woman without previous ovarian hyperstimulation: ultrasound diagnosis and management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 1996;66:193-195.

11. Leach RE, Ney JA, Ory SJ. Selective embryo reduction of an interstitial heterotopic gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1992;7:41-45.

12. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1):216-217.

13. Perez JA, Sadek MM, Savale M, Boyer P, Zorn JR. Local medical treatment of interstitial pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET): two case reports. Hum Reprod. 1993;8(4):631-634.

14. Baker VL, Givens CR, Cadieux MCM. Transvaginal reduction of an interstitial heterotopic pregnancy with preservation of the intrauterine gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):1384-1385.

15. Strohmer H, Obruca A, Lehner R, Egarter C, Husslein P, Feichtinger W. Successful treatment of a heterotopic pregnancy by sonographicallly guided instillation of hyperosmolar glucose. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(1):149-151.

16. Fernandez H, Bourget P, Ville Y, Lelaidier C, Frydman R. Treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy with methotrexate: pharmacokinetic analysis of local versus intramuscular administration. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:943-947.