User login

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

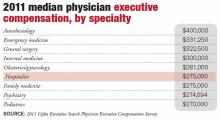

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.