User login

As Medicare and commercial payers rely increasingly on quality outcomes to determine reimbursement levels, clinicians focused on traditional clinical outcomes like length of hospital stay and readmission may be missing the point if they don’t take into consideration more patient-centric outcome. A team of investigators at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston recently evaluated that institution’s tool for measuring patient-reported outcomes in tracking results after thoracic surgery for lung cancer.

Christopher P. Fagundes, Ph.D., led the research team that reported their findings in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.05.057]).

“We used the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) to elicit patient reports of the worst symptoms experienced after thoracic surgery,” Dr. Fagundes and his colleagues said in what may be the first study to use patient-reported outcomes to chart a recovery course after surgery. “This study demonstrates that the MDASI is a sensitive tool for detecting symptomatic recovery with an expected relationship among surgery type, preoperative performance status, and comorbid conditions,” the authors stated.

The MDASI measures the severity of 13 common cancer-related symptoms over the previous 24 hours and rates each on a scale from 0-10, with 10 as most severe. Patients in the study completed a written MDASI questionnaire, 60 upon enrollment, and 77 patients 3 and 5 days after surgery in the hospital. After discharge and for 3 months after surgery, patients received weekly calls from a computer/telephone interactive voice-response system that asked them to rate their symptoms.

All patients were newly diagnosed and treatment naive with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had either standard open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy.

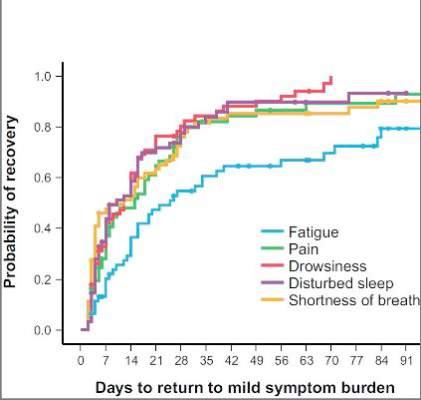

The investigators used a two-pronged approach to define recovery after surgery: symptoms returning to their baseline levels or to a mild level of severity. In the first week after surgery, pain, fatigue, and shortness of breath were “highly prevalent,” perhaps a combined effect from surgical insult and care during and after surgery. After a month, ratings for most symptoms returned to baseline, but fatigue remained the most-persistent symptom during the 3-month study.

NSCLC patients typically have a host of symptoms after major surgery, including inflammation, organ stress, and reaction to medications. In addition, up to a quarter have postsurgical complications that can amplify their symptoms and even delay their course of cancer treatment. The five most-severe postoperative symptoms patients in the study reported were fatigue, pain, shortness of breath, disturbed sleep, and drowsiness.

The median time to return to mild symptom severity for these five symptoms was shorter than return to baseline severity, with fatigue taking longer. Pain recovered significantly faster for patients who underwent VATS lobectomy vs. standard open thoracotomy (8 vs. 18 days, respectively; P = .022), according to the researchers. In addition, the researchers found that patients who had poor preoperative performance status or comorbidities reported significantly higher postoperative pain (P less than .05).

Having the ability to measure patient-reported outcomes allows physicians to identify patients at greatest risk for symptoms after surgery and to help caregivers develop pathways to speed up recovery and get patients to chemotherapy or other cancer treatments on schedule, Dr. Fagundes and his coauthors said.

“Using a straightforward, concise tool like the MDASI to obtain the patient’s perspective on how well he or she is recovering is a clinically relevant and user-friendly method for optimizing perioperative care,” the authors added.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques along with opioid-sparing analgesia have been incorporated into enhanced recovery programs to aim for better objective postoperative outcomes like fewer complications and shorter hospital stays. “Missing from these metrics is the voice of the patient, who is arguably the best source of information about what ‘recovery’ from surgery means,” Dr. Fagundes and colleagues said. “Lack of research on how to define and measure symptomatic and functional recovery after major cancer surgery from the patent’s perspective is an important gap in comprehensive postoperative care; it also compromises any comparison of ERP [enhanced recovery program] innovations against standard care.”

Study coauthors received funding from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant program and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant program. The coauthors reported no conflicts of interest in this work.

“Whether ‘subjective’ or not, the measurements of five common postoperative symptoms appear to reflect the real world experience of many,” Dr. Robert B. Cameron of the University of California, Los Angeles, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.017]).

What’s more, because the study investigators collected patient data after discharge, they eliminated opportunities to “game the system,” in Dr. Cameron’s words. One example of gaming the outcome measures would be to discharge patients early after surgery with a Heimlich chest tube, subjecting them to problems at home and requiring physicians visits and even emergency department care that can go unrecorded.

“Subjective” patient experiences are “real issues,” Dr. Cameron said. “After all, patients are the customers that the health care system serves.”

Patient-reported outcome measures could dramatically influence how physicians and health systems report patient outcomes. “While length of stay (LOS) and hospital complication rates appear to be valid outcome measures to report, in reality, they are outcomes only in a world when hospitals are the ‘customers,’ ” Dr. Cameron said. “In a patient-centric system, when patient outcomes matter, [patient-reported outcomes], such as those proposed by the MD Anderson investigators, are what truly matter.”

“Whether ‘subjective’ or not, the measurements of five common postoperative symptoms appear to reflect the real world experience of many,” Dr. Robert B. Cameron of the University of California, Los Angeles, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.017]).

What’s more, because the study investigators collected patient data after discharge, they eliminated opportunities to “game the system,” in Dr. Cameron’s words. One example of gaming the outcome measures would be to discharge patients early after surgery with a Heimlich chest tube, subjecting them to problems at home and requiring physicians visits and even emergency department care that can go unrecorded.

“Subjective” patient experiences are “real issues,” Dr. Cameron said. “After all, patients are the customers that the health care system serves.”

Patient-reported outcome measures could dramatically influence how physicians and health systems report patient outcomes. “While length of stay (LOS) and hospital complication rates appear to be valid outcome measures to report, in reality, they are outcomes only in a world when hospitals are the ‘customers,’ ” Dr. Cameron said. “In a patient-centric system, when patient outcomes matter, [patient-reported outcomes], such as those proposed by the MD Anderson investigators, are what truly matter.”

“Whether ‘subjective’ or not, the measurements of five common postoperative symptoms appear to reflect the real world experience of many,” Dr. Robert B. Cameron of the University of California, Los Angeles, said in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.017]).

What’s more, because the study investigators collected patient data after discharge, they eliminated opportunities to “game the system,” in Dr. Cameron’s words. One example of gaming the outcome measures would be to discharge patients early after surgery with a Heimlich chest tube, subjecting them to problems at home and requiring physicians visits and even emergency department care that can go unrecorded.

“Subjective” patient experiences are “real issues,” Dr. Cameron said. “After all, patients are the customers that the health care system serves.”

Patient-reported outcome measures could dramatically influence how physicians and health systems report patient outcomes. “While length of stay (LOS) and hospital complication rates appear to be valid outcome measures to report, in reality, they are outcomes only in a world when hospitals are the ‘customers,’ ” Dr. Cameron said. “In a patient-centric system, when patient outcomes matter, [patient-reported outcomes], such as those proposed by the MD Anderson investigators, are what truly matter.”

As Medicare and commercial payers rely increasingly on quality outcomes to determine reimbursement levels, clinicians focused on traditional clinical outcomes like length of hospital stay and readmission may be missing the point if they don’t take into consideration more patient-centric outcome. A team of investigators at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston recently evaluated that institution’s tool for measuring patient-reported outcomes in tracking results after thoracic surgery for lung cancer.

Christopher P. Fagundes, Ph.D., led the research team that reported their findings in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.05.057]).

“We used the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) to elicit patient reports of the worst symptoms experienced after thoracic surgery,” Dr. Fagundes and his colleagues said in what may be the first study to use patient-reported outcomes to chart a recovery course after surgery. “This study demonstrates that the MDASI is a sensitive tool for detecting symptomatic recovery with an expected relationship among surgery type, preoperative performance status, and comorbid conditions,” the authors stated.

The MDASI measures the severity of 13 common cancer-related symptoms over the previous 24 hours and rates each on a scale from 0-10, with 10 as most severe. Patients in the study completed a written MDASI questionnaire, 60 upon enrollment, and 77 patients 3 and 5 days after surgery in the hospital. After discharge and for 3 months after surgery, patients received weekly calls from a computer/telephone interactive voice-response system that asked them to rate their symptoms.

All patients were newly diagnosed and treatment naive with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had either standard open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy.

The investigators used a two-pronged approach to define recovery after surgery: symptoms returning to their baseline levels or to a mild level of severity. In the first week after surgery, pain, fatigue, and shortness of breath were “highly prevalent,” perhaps a combined effect from surgical insult and care during and after surgery. After a month, ratings for most symptoms returned to baseline, but fatigue remained the most-persistent symptom during the 3-month study.

NSCLC patients typically have a host of symptoms after major surgery, including inflammation, organ stress, and reaction to medications. In addition, up to a quarter have postsurgical complications that can amplify their symptoms and even delay their course of cancer treatment. The five most-severe postoperative symptoms patients in the study reported were fatigue, pain, shortness of breath, disturbed sleep, and drowsiness.

The median time to return to mild symptom severity for these five symptoms was shorter than return to baseline severity, with fatigue taking longer. Pain recovered significantly faster for patients who underwent VATS lobectomy vs. standard open thoracotomy (8 vs. 18 days, respectively; P = .022), according to the researchers. In addition, the researchers found that patients who had poor preoperative performance status or comorbidities reported significantly higher postoperative pain (P less than .05).

Having the ability to measure patient-reported outcomes allows physicians to identify patients at greatest risk for symptoms after surgery and to help caregivers develop pathways to speed up recovery and get patients to chemotherapy or other cancer treatments on schedule, Dr. Fagundes and his coauthors said.

“Using a straightforward, concise tool like the MDASI to obtain the patient’s perspective on how well he or she is recovering is a clinically relevant and user-friendly method for optimizing perioperative care,” the authors added.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques along with opioid-sparing analgesia have been incorporated into enhanced recovery programs to aim for better objective postoperative outcomes like fewer complications and shorter hospital stays. “Missing from these metrics is the voice of the patient, who is arguably the best source of information about what ‘recovery’ from surgery means,” Dr. Fagundes and colleagues said. “Lack of research on how to define and measure symptomatic and functional recovery after major cancer surgery from the patent’s perspective is an important gap in comprehensive postoperative care; it also compromises any comparison of ERP [enhanced recovery program] innovations against standard care.”

Study coauthors received funding from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant program and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant program. The coauthors reported no conflicts of interest in this work.

As Medicare and commercial payers rely increasingly on quality outcomes to determine reimbursement levels, clinicians focused on traditional clinical outcomes like length of hospital stay and readmission may be missing the point if they don’t take into consideration more patient-centric outcome. A team of investigators at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston recently evaluated that institution’s tool for measuring patient-reported outcomes in tracking results after thoracic surgery for lung cancer.

Christopher P. Fagundes, Ph.D., led the research team that reported their findings in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.05.057]).

“We used the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) to elicit patient reports of the worst symptoms experienced after thoracic surgery,” Dr. Fagundes and his colleagues said in what may be the first study to use patient-reported outcomes to chart a recovery course after surgery. “This study demonstrates that the MDASI is a sensitive tool for detecting symptomatic recovery with an expected relationship among surgery type, preoperative performance status, and comorbid conditions,” the authors stated.

The MDASI measures the severity of 13 common cancer-related symptoms over the previous 24 hours and rates each on a scale from 0-10, with 10 as most severe. Patients in the study completed a written MDASI questionnaire, 60 upon enrollment, and 77 patients 3 and 5 days after surgery in the hospital. After discharge and for 3 months after surgery, patients received weekly calls from a computer/telephone interactive voice-response system that asked them to rate their symptoms.

All patients were newly diagnosed and treatment naive with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had either standard open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy.

The investigators used a two-pronged approach to define recovery after surgery: symptoms returning to their baseline levels or to a mild level of severity. In the first week after surgery, pain, fatigue, and shortness of breath were “highly prevalent,” perhaps a combined effect from surgical insult and care during and after surgery. After a month, ratings for most symptoms returned to baseline, but fatigue remained the most-persistent symptom during the 3-month study.

NSCLC patients typically have a host of symptoms after major surgery, including inflammation, organ stress, and reaction to medications. In addition, up to a quarter have postsurgical complications that can amplify their symptoms and even delay their course of cancer treatment. The five most-severe postoperative symptoms patients in the study reported were fatigue, pain, shortness of breath, disturbed sleep, and drowsiness.

The median time to return to mild symptom severity for these five symptoms was shorter than return to baseline severity, with fatigue taking longer. Pain recovered significantly faster for patients who underwent VATS lobectomy vs. standard open thoracotomy (8 vs. 18 days, respectively; P = .022), according to the researchers. In addition, the researchers found that patients who had poor preoperative performance status or comorbidities reported significantly higher postoperative pain (P less than .05).

Having the ability to measure patient-reported outcomes allows physicians to identify patients at greatest risk for symptoms after surgery and to help caregivers develop pathways to speed up recovery and get patients to chemotherapy or other cancer treatments on schedule, Dr. Fagundes and his coauthors said.

“Using a straightforward, concise tool like the MDASI to obtain the patient’s perspective on how well he or she is recovering is a clinically relevant and user-friendly method for optimizing perioperative care,” the authors added.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques along with opioid-sparing analgesia have been incorporated into enhanced recovery programs to aim for better objective postoperative outcomes like fewer complications and shorter hospital stays. “Missing from these metrics is the voice of the patient, who is arguably the best source of information about what ‘recovery’ from surgery means,” Dr. Fagundes and colleagues said. “Lack of research on how to define and measure symptomatic and functional recovery after major cancer surgery from the patent’s perspective is an important gap in comprehensive postoperative care; it also compromises any comparison of ERP [enhanced recovery program] innovations against standard care.”

Study coauthors received funding from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant program and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant program. The coauthors reported no conflicts of interest in this work.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory to elicit patient-reported symptom burden is a simple, clinically relevant way to optimize care after thoracic surgery for lung cancer.

Major finding: Assessing symptoms from the patient’s perspective throughout the postoperative recovery period is an effective strategy for evaluating perioperative care.

Data source: Sixty newly diagnosed patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer scheduled for thoracic surgery prospectively were recruited for evaluation.

Disclosures: Study coauthors received funding from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant program, and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant program. The coauthors reported no conflicts of interest in this work.