User login

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

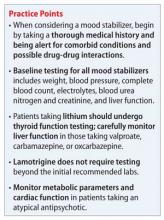

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.