User login

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

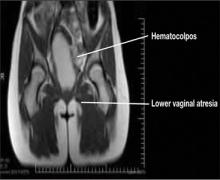

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

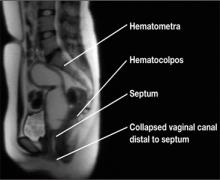

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.