User login

A sea change in management of severe heart failure began two and a half years ago, in January 2010, when the Food and Drug Administration approved U.S. marketing of the HeartMate II continuous-flow, left ventricular assist device for destination therapy. Patients, cardiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons at last had a reasonably durable, effective, and relatively safe alternative to heart transplant to offer patients at the end stage of deteriorating heart function.

The Heart Mate II quickly supplanted the prior-generation, pulsatile-flow devices, and 2010 also saw a 10-fold spike in the number of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) placed in U.S. patients as destination therapy.

During the first half of 2011, 6-month survival among U.S. patients with a continuous-flow LVAD (which means the HeartMate II, the only continuous-flow device on the U.S. market) was 89%, and 12-month survival during 2010 was 81% (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26, putting the continuous-flow LVAD in at least the same ballpark as heart transplant, which has a 5-year survival of about 80% and a median survival of about 10 years in U.S. patients.

But despite estimates that many thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Americans meet the clinical criteria to qualify for placement of an LVAD, the reality is that in the 30 months since the HeartMate II became available for routine destination therapy through mid-2012, only about 4,600 were placed in U.S. patients. In addition, just slightly more than a third of those patients, roughly 1,700, received their LVAD explicitly for destination therapy.

Even in 2012, a majority of patients who received an LVAD got their device with the understanding that it was as a bridge to transplant, an LVAD placed with temporary intent to help patients survive and improve clinically until their LVAD could be swapped out and replaced by a transplanted heart.

LVAD Numbers Up, but Still Low

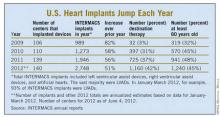

If the availability of the HeartMate II for destination therapy in routine practice was a revolution for the management of many patients with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure – which is how many experts in this field view the device – it has so far been a revolution played out in slow motion. In large part that’s because the field started small, and stayed small until recently. At the end of 2008, fewer than 1,000 patients had ever received a ventricular assist device or a total artificial heart. Even though the number nearly doubled in 2009, by decade’s end the cumulative total still remained under 2,000.

Despite the low numbers compared with the estimated need, many physicians and surgeons who specialize in advanced heart failure say they are satisfied with the pace at which continuous-flow LVADs have entered patients over the past 2 years. Though they acknowledge that the number of potential U.S. candidates for an LVAD undoubtedly is far larger than the nearly 4,600 who received one since early 2010, they note that the implantation rate grew in a steady and robust way during the past 30 months, as has the number of centers performing the surgery. With a better-than-50% year-over-year growth spurt in both 2010 and 2011, and with that pace continuing into the first months of 2012, the 140 U.S. centers that now place LVADs are on track to do nearly 3,000 this year (although only 42% were for destination therapy during January-March 2012).

"You probably don’t want it to increase too rapidly, because it is still high risk and expensive," said Dr. David E. Lanfear, a cardiologist specializing in advanced heart failure and transplantation at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. LVAD placements "have not reached the maximum number of patients who they could help, but you need to be cautious because it requires specialized expertise to do it properly. I wouldn’t expect that [during 2 years] it would immediately reach maximum use. It’s still in the growth phase. There are a lot of patients out there, so it will continue to grow; I’m not concerned that it’s not growing fast enough," he said in an interview.

An LVAD or a Heart Transplant?

Experts also note an important shift in attitude about the role for LVADs, a change that has brought them to the brink of replacing transplanted hearts as the default treatment for patients with end-stage heart failure.

"The current outcomes with HeartMate II have already changed the field. We published a paper last year that showed there was no difference between LVADs and transplant in costs and outcomes at 1 year (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:1330-4)," said Dr. Mark S. Slaughter, professor of surgery and chief of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Between that and the competitive mortality benefit from LVADs "we need to rethink the role of transplant. In appropriately selected patients, we can achieve outstanding long-term results with limited adverse events."

In their 2011 paper, Dr. Slaughter and his associates put the pending change more bluntly: "As outcomes for continuous-flow LVADs and heart transplantation converge, the therapy of heart transplantation could emerge as salvage therapy for major device-related complications or dysfunction or progressive right heart failure as opposed to the default option for all patients who are eligible for transplant."

Despite their huge promise, some experts have lingering concerns about the current generation of continuous-flow LVADs that make them reluctant to say that heart transplant has unquestionably stepped down from its pedestal as the gold standard treatment for patients with severe, end-stage heart failure.

"There is no question that [current continuous-flow LVADs] are very good technology. But whether they are great technology remains to be proven," said Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "We still have important concerns about things like drive-line infections and thromboembolic complications. Neither rate is terribly high, but they are high enough to be a problem if you apply LVADs to patients who are doing okay. We still have important doubts about whether we can really mimic the quality of life" achieved by transplant, he said in an interview.

LVAD placement also poses an operative risk, which may be as high as 10%, said Dr. David Taylor, a cardiologist and advanced heart failure specialist at the Cleveland Clinic. "If the risk was 2% or 3%, I’d say do it, but a risk closer to 10% makes you hesitate.

"There are a lot of really sick, elderly patients with heart failure who could unquestionably benefit from an LVAD. But as soon as you push the envelope [by treating sicker patients] you increase mortality. A large group of heart failure patients are very ill with chronic disease and feel terrible, and these are the patients where you’d see the greatest benefit, but we can’t afford to do that. We can’t afford to allocate this resource to patients with a 30% mortality risk, because that would limit our ability to extend it to other patients," Dr. Kirklin said in an interview.

"Most patients appreciate an LVAD and like it, but they still look forward to getting a transplant," said Dr. Stephen H. Bailey, director of cardiothoracic surgery at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh. "In July 2012, while the margin between LVAD and transplant is narrowing, transplant is still the gold standard for definitive treatment. Most patients still favor transplant, but that might change. It’s not quite there yet that an LVAD is equal to a transplant for the long term. It also requires getting rid of the drive line. That would be a game changer. It would also help if we could reduce gastrointestinal bleeds, but that is more of a nuisance."

Part of the bleeding problem comes from anticoagulation treatment to prevent clots from forming in the LVAD, but another facet is an acquired Von Willebrand factor deficiency caused by absent pulsatile blood flow, Dr. Bailey said. Early clinical results suggest that allowing the heart to beat every few seconds, by adjusting the LVAD’s continuous flow rate, can minimize the acquired deficiency.

Which INTERMACS Level?

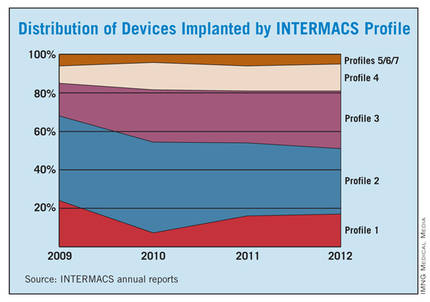

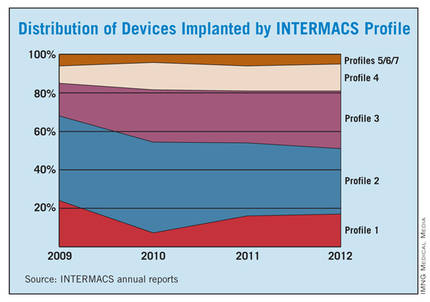

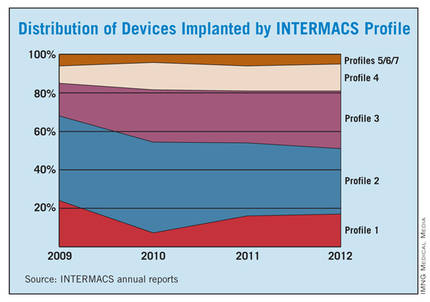

The most widely used gauge physicians and surgeons have for assessing LVAD candidates is their level in a seven-step sequence created by INTERMACS (the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support), which subdivides a patient’s descent from advanced New York Heart Association class III heart failure through the strata of class IV disease. (See table.) The most severe INTERMACS stage, level 1 patients (also known as "crash and burn") are those in cardiogenic shock. During the past year or two, about 16% of U.S. LVAD recipients have been level 1 patients, a percentage that should ideally drop much closer to zero, experts say.

But beyond the maxim that an advanced heart failure patient should get an LVAD before reaching level 1, opinions vary on the best target.

"Everyone agrees that inotrope-dependent patients [profile 2 and 3] should get an LVAD," said Dr. Lanfear. "But you definitely should not wait until INTERMACS 1 or 2. Everyone tries hard to treat level 3 and 4 patients. Level 5 is controversial. We need more data about these clearly less- sick patients."

"INTERMACS 2 and 3 is the sweet spot. Patients in INTERMACS 4, 5, or 6 are not as motivated to be connected to a device and undergo big open heart surgery," said Dr. Bailey.

"When patients are on the cusp of inotrope dependence [before they reach level 3], I start to think about implanting," said Dr. Jeffrey J. Teuteberg, a cardiologist and associate director of the cardiac transplant program at the University of Pittsburgh. "It’s nice to get patients who are pre–inotrope dependent – profile 4, 5, or 6 – but are symptom limited and quality of life limited. For destination therapy, you want patients with function and good quality of life. Mechanical support provides more than just improved survival; it also reduces adverse events and raises quality of life."

"For level 2 patients, there is no question that an LVAD as bridge to transplant is better than continued medical treatment," said Dr. Taylor. "For level 3 patients, it’s a little trickier, but I think the majority would say that if a patient is stable and inotropic dependent, use an LVAD unless you believe a transplant will occur quickly. An LVAD would reduce the risk for developing cardiogenic shock. The patient who does the best with an LVAD is the one who is [relatively] healthy when implanted, but the patient who needs it most is the one who is literally dying."

"Everyone knows that if you take patients who are sicker [for LVADs], you’ll have trouble reaching 80% survival after 2 years. But there is not yet enough confidence in the treatment to extend it to INTERMACS level 4, 5, or 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "That’s where the big potential is. The action currently is in INTERMACS 2 and 3. For patients who are INTERMACS 3, there is no question that if they can’t get a transplant they need a VAD. The sweet spot will be patients at INTERMACS 4."

The INTERMACS registry numbers show that the field is currently stuck when it comes to INTERMACS levels, with the greatest number of LVADs going into level 2 patients, who received 34% of U.S LVADS during January-March 2012. The 34% level in early 2012 was down from 38% of LVAD recipients in 2011 and 47% in 2010, but growth in less-severe levels has been slow. At the start of 2012, 30% of LVAD recipients were at level 3, a small increase from the 27% rate in 2011 and 2010. Level 4 patients constituted 14% of LVAD recipients in early 2012, essentially unchanged from the prior 2 years, and level 5, 6, or 7 patients have consistently been a small slice of the U.S. LVAD pie, roughly 5% of recipients each year.

Beyond the INTERMACS Level

Heart failure specialists now recognize that INTERMACS level tells just part of the story.

"INTERMACS profiles depend on heart failure symptoms but not comorbidities. Severe diabetes, obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiorenal syndrome, chronic malnourishment, morbid obesity, and other factors all fall outside the INTERMACS profile criteria," said Dr. Kirklin.

He and his associates are formulating a risk assessment equation that will take comorbidities into account for a more global patient assessment. The most recently published INTERMACS registry analysis, which he first authored using data through the end of June 2011 with a total of 4,366 patients who received left ventricular support since 2006 (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26), identified several comorbidity markers that each significantly linked with increased mortality. For example, a 1-unit increase in bilirubin linked with a 10% boost in mortality, a 1-unit increase in creatinine raised mortality by 16%, and a 0.5-unit increase in body surface area linked with a 48% rise in deaths. One of the strongest risk factors was being at INTERMACS level 1, which linked with a more-than-threefold higher mortality rate.

But more work must be done before the risk assessment formula is ready for clinical use. Right now, the formula "is not very reliable yet, because the maximum patient follow-up is 2 years. We need a little more follow-up," Dr. Kirklin said.

Growing the LVAD Numbers

Further growth in LVAD placements will happen on two fronts: broader use in patients at INTERMACS levels 2 and 3, and possibly level 4, where a strong consensus exists for LVAD support; and new evidence to document efficacy and safety in patients with less-severe disease at INTERMACS levels 4, 5, 6, and 7.

For the existing population, it’s a matter of physician and patient awareness. "We need to educate physicians that this is an option," said Dr. Lanfear. "Awareness is lacking. There is a lot of heart failure out there that is underrecognized and underreferred. Neither patients nor their physicians realize how sick they are, and that they are at a high enough risk to justify this."

Furthermore, there are parts of the country where the technology is underused. "In areas without a big center nearby, some physicians may not recognize patients who are sick enough to be LVAD candidates. We are trying to spread the word on who these patients are and when they should be referred."

According to Dr. Teuteberg, major warning signs that should flag patients who are potential LVAD candidates include advanced symptoms, increasing numbers of hospitalizations for heart failure, dwindling responses to ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers, increasing dosages of diuretics, a persistently high serum level of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) despite good medical treatment, and lack of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Expansion of the evidence base to show LVAD benefits in patients with INTERMACS level 5, 6, or 7 disease depends on a trial just starting, the REVIVE-IT (Randomized Evaluation of VAD Intervention Before Inotropic Therapy) study that’s set to enroll about 100 patients. But at press time, REVIVE-IT had not yet begun, posing doubts about LVAD use in the study’s targeted patients. "We haven’t really demonstrated reproducibly good survival [with LVADs] to compete with medical therapy in level 5 and 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "The FDA put the study on hold while they reflected on that."

Making LVADs Better

With fast-paced technological advancement, continuous-flow LVADs will continue to evolve and improve. In June, results appeared on a new continuous-flow LVAD, the HeartWare device (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200), and last April an FDA advisory committee recommended that the agency approve the HeartWare LVAD for use as a bridge to (a trial testing the HeartWare LVAD for destination therapy is ongoing).

But no one interviewed for this article anticipates that the HeartWare LVAD will be a major advance. "Fundamentally, the major components and the implant technique are the same for the two devices," the HeartWare and the HeartMate II, said Dr. Slaughter. The HeartWare LVAD is smaller and designed to be placed completely in the pericardial space, but any clinical advantages based on these differences remain to be proved, he said in an interview.

A more meaningful improvement in LVAD design is in the works, and may reach initial clinical testing within a couple of years: a fully implantable LVAD with no transcutaneous drive line, a part that is subject to infection, prevents patients from submerging, and physically and psychologically limits patients by tethering them to equipment. "If there were one thing that could make a dramatic difference, it would be getting rid of the drive line. That is the Holy Grail for the field," said Dr. Bailey.

When a fully implantable LVAD becomes available for routine use, it will complete the LVAD revolution and help device therapy for advanced heart failure reach its full potential.

Dr. Lanfear has received research support and has received honoraria as a speaker for Thoratec, the company that markets the HeartMate II, and has received research support from HeartWare, the company developing the HeartWare LVAD. Dr. Slaughter has had contracts for services to Thoratec and HeartWare. Dr. Kirklin, Dr. Bailey, Dr. Teuteberg, and Dr. Taylor said that they had no disclosures.

*CORRECTION 8/10/12: The credit for the photo with the caption "The next LVAD in line, HeartWare, is smaller and dwells in the pericardial space" was misstated and should have been ©2012 HeartWare International, Inc.

A sea change in management of severe heart failure began two and a half years ago, in January 2010, when the Food and Drug Administration approved U.S. marketing of the HeartMate II continuous-flow, left ventricular assist device for destination therapy. Patients, cardiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons at last had a reasonably durable, effective, and relatively safe alternative to heart transplant to offer patients at the end stage of deteriorating heart function.

The Heart Mate II quickly supplanted the prior-generation, pulsatile-flow devices, and 2010 also saw a 10-fold spike in the number of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) placed in U.S. patients as destination therapy.

During the first half of 2011, 6-month survival among U.S. patients with a continuous-flow LVAD (which means the HeartMate II, the only continuous-flow device on the U.S. market) was 89%, and 12-month survival during 2010 was 81% (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26, putting the continuous-flow LVAD in at least the same ballpark as heart transplant, which has a 5-year survival of about 80% and a median survival of about 10 years in U.S. patients.

But despite estimates that many thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Americans meet the clinical criteria to qualify for placement of an LVAD, the reality is that in the 30 months since the HeartMate II became available for routine destination therapy through mid-2012, only about 4,600 were placed in U.S. patients. In addition, just slightly more than a third of those patients, roughly 1,700, received their LVAD explicitly for destination therapy.

Even in 2012, a majority of patients who received an LVAD got their device with the understanding that it was as a bridge to transplant, an LVAD placed with temporary intent to help patients survive and improve clinically until their LVAD could be swapped out and replaced by a transplanted heart.

LVAD Numbers Up, but Still Low

If the availability of the HeartMate II for destination therapy in routine practice was a revolution for the management of many patients with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure – which is how many experts in this field view the device – it has so far been a revolution played out in slow motion. In large part that’s because the field started small, and stayed small until recently. At the end of 2008, fewer than 1,000 patients had ever received a ventricular assist device or a total artificial heart. Even though the number nearly doubled in 2009, by decade’s end the cumulative total still remained under 2,000.

Despite the low numbers compared with the estimated need, many physicians and surgeons who specialize in advanced heart failure say they are satisfied with the pace at which continuous-flow LVADs have entered patients over the past 2 years. Though they acknowledge that the number of potential U.S. candidates for an LVAD undoubtedly is far larger than the nearly 4,600 who received one since early 2010, they note that the implantation rate grew in a steady and robust way during the past 30 months, as has the number of centers performing the surgery. With a better-than-50% year-over-year growth spurt in both 2010 and 2011, and with that pace continuing into the first months of 2012, the 140 U.S. centers that now place LVADs are on track to do nearly 3,000 this year (although only 42% were for destination therapy during January-March 2012).

"You probably don’t want it to increase too rapidly, because it is still high risk and expensive," said Dr. David E. Lanfear, a cardiologist specializing in advanced heart failure and transplantation at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. LVAD placements "have not reached the maximum number of patients who they could help, but you need to be cautious because it requires specialized expertise to do it properly. I wouldn’t expect that [during 2 years] it would immediately reach maximum use. It’s still in the growth phase. There are a lot of patients out there, so it will continue to grow; I’m not concerned that it’s not growing fast enough," he said in an interview.

An LVAD or a Heart Transplant?

Experts also note an important shift in attitude about the role for LVADs, a change that has brought them to the brink of replacing transplanted hearts as the default treatment for patients with end-stage heart failure.

"The current outcomes with HeartMate II have already changed the field. We published a paper last year that showed there was no difference between LVADs and transplant in costs and outcomes at 1 year (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:1330-4)," said Dr. Mark S. Slaughter, professor of surgery and chief of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Between that and the competitive mortality benefit from LVADs "we need to rethink the role of transplant. In appropriately selected patients, we can achieve outstanding long-term results with limited adverse events."

In their 2011 paper, Dr. Slaughter and his associates put the pending change more bluntly: "As outcomes for continuous-flow LVADs and heart transplantation converge, the therapy of heart transplantation could emerge as salvage therapy for major device-related complications or dysfunction or progressive right heart failure as opposed to the default option for all patients who are eligible for transplant."

Despite their huge promise, some experts have lingering concerns about the current generation of continuous-flow LVADs that make them reluctant to say that heart transplant has unquestionably stepped down from its pedestal as the gold standard treatment for patients with severe, end-stage heart failure.

"There is no question that [current continuous-flow LVADs] are very good technology. But whether they are great technology remains to be proven," said Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "We still have important concerns about things like drive-line infections and thromboembolic complications. Neither rate is terribly high, but they are high enough to be a problem if you apply LVADs to patients who are doing okay. We still have important doubts about whether we can really mimic the quality of life" achieved by transplant, he said in an interview.

LVAD placement also poses an operative risk, which may be as high as 10%, said Dr. David Taylor, a cardiologist and advanced heart failure specialist at the Cleveland Clinic. "If the risk was 2% or 3%, I’d say do it, but a risk closer to 10% makes you hesitate.

"There are a lot of really sick, elderly patients with heart failure who could unquestionably benefit from an LVAD. But as soon as you push the envelope [by treating sicker patients] you increase mortality. A large group of heart failure patients are very ill with chronic disease and feel terrible, and these are the patients where you’d see the greatest benefit, but we can’t afford to do that. We can’t afford to allocate this resource to patients with a 30% mortality risk, because that would limit our ability to extend it to other patients," Dr. Kirklin said in an interview.

"Most patients appreciate an LVAD and like it, but they still look forward to getting a transplant," said Dr. Stephen H. Bailey, director of cardiothoracic surgery at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh. "In July 2012, while the margin between LVAD and transplant is narrowing, transplant is still the gold standard for definitive treatment. Most patients still favor transplant, but that might change. It’s not quite there yet that an LVAD is equal to a transplant for the long term. It also requires getting rid of the drive line. That would be a game changer. It would also help if we could reduce gastrointestinal bleeds, but that is more of a nuisance."

Part of the bleeding problem comes from anticoagulation treatment to prevent clots from forming in the LVAD, but another facet is an acquired Von Willebrand factor deficiency caused by absent pulsatile blood flow, Dr. Bailey said. Early clinical results suggest that allowing the heart to beat every few seconds, by adjusting the LVAD’s continuous flow rate, can minimize the acquired deficiency.

Which INTERMACS Level?

The most widely used gauge physicians and surgeons have for assessing LVAD candidates is their level in a seven-step sequence created by INTERMACS (the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support), which subdivides a patient’s descent from advanced New York Heart Association class III heart failure through the strata of class IV disease. (See table.) The most severe INTERMACS stage, level 1 patients (also known as "crash and burn") are those in cardiogenic shock. During the past year or two, about 16% of U.S. LVAD recipients have been level 1 patients, a percentage that should ideally drop much closer to zero, experts say.

But beyond the maxim that an advanced heart failure patient should get an LVAD before reaching level 1, opinions vary on the best target.

"Everyone agrees that inotrope-dependent patients [profile 2 and 3] should get an LVAD," said Dr. Lanfear. "But you definitely should not wait until INTERMACS 1 or 2. Everyone tries hard to treat level 3 and 4 patients. Level 5 is controversial. We need more data about these clearly less- sick patients."

"INTERMACS 2 and 3 is the sweet spot. Patients in INTERMACS 4, 5, or 6 are not as motivated to be connected to a device and undergo big open heart surgery," said Dr. Bailey.

"When patients are on the cusp of inotrope dependence [before they reach level 3], I start to think about implanting," said Dr. Jeffrey J. Teuteberg, a cardiologist and associate director of the cardiac transplant program at the University of Pittsburgh. "It’s nice to get patients who are pre–inotrope dependent – profile 4, 5, or 6 – but are symptom limited and quality of life limited. For destination therapy, you want patients with function and good quality of life. Mechanical support provides more than just improved survival; it also reduces adverse events and raises quality of life."

"For level 2 patients, there is no question that an LVAD as bridge to transplant is better than continued medical treatment," said Dr. Taylor. "For level 3 patients, it’s a little trickier, but I think the majority would say that if a patient is stable and inotropic dependent, use an LVAD unless you believe a transplant will occur quickly. An LVAD would reduce the risk for developing cardiogenic shock. The patient who does the best with an LVAD is the one who is [relatively] healthy when implanted, but the patient who needs it most is the one who is literally dying."

"Everyone knows that if you take patients who are sicker [for LVADs], you’ll have trouble reaching 80% survival after 2 years. But there is not yet enough confidence in the treatment to extend it to INTERMACS level 4, 5, or 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "That’s where the big potential is. The action currently is in INTERMACS 2 and 3. For patients who are INTERMACS 3, there is no question that if they can’t get a transplant they need a VAD. The sweet spot will be patients at INTERMACS 4."

The INTERMACS registry numbers show that the field is currently stuck when it comes to INTERMACS levels, with the greatest number of LVADs going into level 2 patients, who received 34% of U.S LVADS during January-March 2012. The 34% level in early 2012 was down from 38% of LVAD recipients in 2011 and 47% in 2010, but growth in less-severe levels has been slow. At the start of 2012, 30% of LVAD recipients were at level 3, a small increase from the 27% rate in 2011 and 2010. Level 4 patients constituted 14% of LVAD recipients in early 2012, essentially unchanged from the prior 2 years, and level 5, 6, or 7 patients have consistently been a small slice of the U.S. LVAD pie, roughly 5% of recipients each year.

Beyond the INTERMACS Level

Heart failure specialists now recognize that INTERMACS level tells just part of the story.

"INTERMACS profiles depend on heart failure symptoms but not comorbidities. Severe diabetes, obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiorenal syndrome, chronic malnourishment, morbid obesity, and other factors all fall outside the INTERMACS profile criteria," said Dr. Kirklin.

He and his associates are formulating a risk assessment equation that will take comorbidities into account for a more global patient assessment. The most recently published INTERMACS registry analysis, which he first authored using data through the end of June 2011 with a total of 4,366 patients who received left ventricular support since 2006 (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26), identified several comorbidity markers that each significantly linked with increased mortality. For example, a 1-unit increase in bilirubin linked with a 10% boost in mortality, a 1-unit increase in creatinine raised mortality by 16%, and a 0.5-unit increase in body surface area linked with a 48% rise in deaths. One of the strongest risk factors was being at INTERMACS level 1, which linked with a more-than-threefold higher mortality rate.

But more work must be done before the risk assessment formula is ready for clinical use. Right now, the formula "is not very reliable yet, because the maximum patient follow-up is 2 years. We need a little more follow-up," Dr. Kirklin said.

Growing the LVAD Numbers

Further growth in LVAD placements will happen on two fronts: broader use in patients at INTERMACS levels 2 and 3, and possibly level 4, where a strong consensus exists for LVAD support; and new evidence to document efficacy and safety in patients with less-severe disease at INTERMACS levels 4, 5, 6, and 7.

For the existing population, it’s a matter of physician and patient awareness. "We need to educate physicians that this is an option," said Dr. Lanfear. "Awareness is lacking. There is a lot of heart failure out there that is underrecognized and underreferred. Neither patients nor their physicians realize how sick they are, and that they are at a high enough risk to justify this."

Furthermore, there are parts of the country where the technology is underused. "In areas without a big center nearby, some physicians may not recognize patients who are sick enough to be LVAD candidates. We are trying to spread the word on who these patients are and when they should be referred."

According to Dr. Teuteberg, major warning signs that should flag patients who are potential LVAD candidates include advanced symptoms, increasing numbers of hospitalizations for heart failure, dwindling responses to ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers, increasing dosages of diuretics, a persistently high serum level of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) despite good medical treatment, and lack of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Expansion of the evidence base to show LVAD benefits in patients with INTERMACS level 5, 6, or 7 disease depends on a trial just starting, the REVIVE-IT (Randomized Evaluation of VAD Intervention Before Inotropic Therapy) study that’s set to enroll about 100 patients. But at press time, REVIVE-IT had not yet begun, posing doubts about LVAD use in the study’s targeted patients. "We haven’t really demonstrated reproducibly good survival [with LVADs] to compete with medical therapy in level 5 and 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "The FDA put the study on hold while they reflected on that."

Making LVADs Better

With fast-paced technological advancement, continuous-flow LVADs will continue to evolve and improve. In June, results appeared on a new continuous-flow LVAD, the HeartWare device (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200), and last April an FDA advisory committee recommended that the agency approve the HeartWare LVAD for use as a bridge to (a trial testing the HeartWare LVAD for destination therapy is ongoing).

But no one interviewed for this article anticipates that the HeartWare LVAD will be a major advance. "Fundamentally, the major components and the implant technique are the same for the two devices," the HeartWare and the HeartMate II, said Dr. Slaughter. The HeartWare LVAD is smaller and designed to be placed completely in the pericardial space, but any clinical advantages based on these differences remain to be proved, he said in an interview.

A more meaningful improvement in LVAD design is in the works, and may reach initial clinical testing within a couple of years: a fully implantable LVAD with no transcutaneous drive line, a part that is subject to infection, prevents patients from submerging, and physically and psychologically limits patients by tethering them to equipment. "If there were one thing that could make a dramatic difference, it would be getting rid of the drive line. That is the Holy Grail for the field," said Dr. Bailey.

When a fully implantable LVAD becomes available for routine use, it will complete the LVAD revolution and help device therapy for advanced heart failure reach its full potential.

Dr. Lanfear has received research support and has received honoraria as a speaker for Thoratec, the company that markets the HeartMate II, and has received research support from HeartWare, the company developing the HeartWare LVAD. Dr. Slaughter has had contracts for services to Thoratec and HeartWare. Dr. Kirklin, Dr. Bailey, Dr. Teuteberg, and Dr. Taylor said that they had no disclosures.

*CORRECTION 8/10/12: The credit for the photo with the caption "The next LVAD in line, HeartWare, is smaller and dwells in the pericardial space" was misstated and should have been ©2012 HeartWare International, Inc.

A sea change in management of severe heart failure began two and a half years ago, in January 2010, when the Food and Drug Administration approved U.S. marketing of the HeartMate II continuous-flow, left ventricular assist device for destination therapy. Patients, cardiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons at last had a reasonably durable, effective, and relatively safe alternative to heart transplant to offer patients at the end stage of deteriorating heart function.

The Heart Mate II quickly supplanted the prior-generation, pulsatile-flow devices, and 2010 also saw a 10-fold spike in the number of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) placed in U.S. patients as destination therapy.

During the first half of 2011, 6-month survival among U.S. patients with a continuous-flow LVAD (which means the HeartMate II, the only continuous-flow device on the U.S. market) was 89%, and 12-month survival during 2010 was 81% (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26, putting the continuous-flow LVAD in at least the same ballpark as heart transplant, which has a 5-year survival of about 80% and a median survival of about 10 years in U.S. patients.

But despite estimates that many thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Americans meet the clinical criteria to qualify for placement of an LVAD, the reality is that in the 30 months since the HeartMate II became available for routine destination therapy through mid-2012, only about 4,600 were placed in U.S. patients. In addition, just slightly more than a third of those patients, roughly 1,700, received their LVAD explicitly for destination therapy.

Even in 2012, a majority of patients who received an LVAD got their device with the understanding that it was as a bridge to transplant, an LVAD placed with temporary intent to help patients survive and improve clinically until their LVAD could be swapped out and replaced by a transplanted heart.

LVAD Numbers Up, but Still Low

If the availability of the HeartMate II for destination therapy in routine practice was a revolution for the management of many patients with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure – which is how many experts in this field view the device – it has so far been a revolution played out in slow motion. In large part that’s because the field started small, and stayed small until recently. At the end of 2008, fewer than 1,000 patients had ever received a ventricular assist device or a total artificial heart. Even though the number nearly doubled in 2009, by decade’s end the cumulative total still remained under 2,000.

Despite the low numbers compared with the estimated need, many physicians and surgeons who specialize in advanced heart failure say they are satisfied with the pace at which continuous-flow LVADs have entered patients over the past 2 years. Though they acknowledge that the number of potential U.S. candidates for an LVAD undoubtedly is far larger than the nearly 4,600 who received one since early 2010, they note that the implantation rate grew in a steady and robust way during the past 30 months, as has the number of centers performing the surgery. With a better-than-50% year-over-year growth spurt in both 2010 and 2011, and with that pace continuing into the first months of 2012, the 140 U.S. centers that now place LVADs are on track to do nearly 3,000 this year (although only 42% were for destination therapy during January-March 2012).

"You probably don’t want it to increase too rapidly, because it is still high risk and expensive," said Dr. David E. Lanfear, a cardiologist specializing in advanced heart failure and transplantation at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. LVAD placements "have not reached the maximum number of patients who they could help, but you need to be cautious because it requires specialized expertise to do it properly. I wouldn’t expect that [during 2 years] it would immediately reach maximum use. It’s still in the growth phase. There are a lot of patients out there, so it will continue to grow; I’m not concerned that it’s not growing fast enough," he said in an interview.

An LVAD or a Heart Transplant?

Experts also note an important shift in attitude about the role for LVADs, a change that has brought them to the brink of replacing transplanted hearts as the default treatment for patients with end-stage heart failure.

"The current outcomes with HeartMate II have already changed the field. We published a paper last year that showed there was no difference between LVADs and transplant in costs and outcomes at 1 year (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:1330-4)," said Dr. Mark S. Slaughter, professor of surgery and chief of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Between that and the competitive mortality benefit from LVADs "we need to rethink the role of transplant. In appropriately selected patients, we can achieve outstanding long-term results with limited adverse events."

In their 2011 paper, Dr. Slaughter and his associates put the pending change more bluntly: "As outcomes for continuous-flow LVADs and heart transplantation converge, the therapy of heart transplantation could emerge as salvage therapy for major device-related complications or dysfunction or progressive right heart failure as opposed to the default option for all patients who are eligible for transplant."

Despite their huge promise, some experts have lingering concerns about the current generation of continuous-flow LVADs that make them reluctant to say that heart transplant has unquestionably stepped down from its pedestal as the gold standard treatment for patients with severe, end-stage heart failure.

"There is no question that [current continuous-flow LVADs] are very good technology. But whether they are great technology remains to be proven," said Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "We still have important concerns about things like drive-line infections and thromboembolic complications. Neither rate is terribly high, but they are high enough to be a problem if you apply LVADs to patients who are doing okay. We still have important doubts about whether we can really mimic the quality of life" achieved by transplant, he said in an interview.

LVAD placement also poses an operative risk, which may be as high as 10%, said Dr. David Taylor, a cardiologist and advanced heart failure specialist at the Cleveland Clinic. "If the risk was 2% or 3%, I’d say do it, but a risk closer to 10% makes you hesitate.

"There are a lot of really sick, elderly patients with heart failure who could unquestionably benefit from an LVAD. But as soon as you push the envelope [by treating sicker patients] you increase mortality. A large group of heart failure patients are very ill with chronic disease and feel terrible, and these are the patients where you’d see the greatest benefit, but we can’t afford to do that. We can’t afford to allocate this resource to patients with a 30% mortality risk, because that would limit our ability to extend it to other patients," Dr. Kirklin said in an interview.

"Most patients appreciate an LVAD and like it, but they still look forward to getting a transplant," said Dr. Stephen H. Bailey, director of cardiothoracic surgery at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh. "In July 2012, while the margin between LVAD and transplant is narrowing, transplant is still the gold standard for definitive treatment. Most patients still favor transplant, but that might change. It’s not quite there yet that an LVAD is equal to a transplant for the long term. It also requires getting rid of the drive line. That would be a game changer. It would also help if we could reduce gastrointestinal bleeds, but that is more of a nuisance."

Part of the bleeding problem comes from anticoagulation treatment to prevent clots from forming in the LVAD, but another facet is an acquired Von Willebrand factor deficiency caused by absent pulsatile blood flow, Dr. Bailey said. Early clinical results suggest that allowing the heart to beat every few seconds, by adjusting the LVAD’s continuous flow rate, can minimize the acquired deficiency.

Which INTERMACS Level?

The most widely used gauge physicians and surgeons have for assessing LVAD candidates is their level in a seven-step sequence created by INTERMACS (the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support), which subdivides a patient’s descent from advanced New York Heart Association class III heart failure through the strata of class IV disease. (See table.) The most severe INTERMACS stage, level 1 patients (also known as "crash and burn") are those in cardiogenic shock. During the past year or two, about 16% of U.S. LVAD recipients have been level 1 patients, a percentage that should ideally drop much closer to zero, experts say.

But beyond the maxim that an advanced heart failure patient should get an LVAD before reaching level 1, opinions vary on the best target.

"Everyone agrees that inotrope-dependent patients [profile 2 and 3] should get an LVAD," said Dr. Lanfear. "But you definitely should not wait until INTERMACS 1 or 2. Everyone tries hard to treat level 3 and 4 patients. Level 5 is controversial. We need more data about these clearly less- sick patients."

"INTERMACS 2 and 3 is the sweet spot. Patients in INTERMACS 4, 5, or 6 are not as motivated to be connected to a device and undergo big open heart surgery," said Dr. Bailey.

"When patients are on the cusp of inotrope dependence [before they reach level 3], I start to think about implanting," said Dr. Jeffrey J. Teuteberg, a cardiologist and associate director of the cardiac transplant program at the University of Pittsburgh. "It’s nice to get patients who are pre–inotrope dependent – profile 4, 5, or 6 – but are symptom limited and quality of life limited. For destination therapy, you want patients with function and good quality of life. Mechanical support provides more than just improved survival; it also reduces adverse events and raises quality of life."

"For level 2 patients, there is no question that an LVAD as bridge to transplant is better than continued medical treatment," said Dr. Taylor. "For level 3 patients, it’s a little trickier, but I think the majority would say that if a patient is stable and inotropic dependent, use an LVAD unless you believe a transplant will occur quickly. An LVAD would reduce the risk for developing cardiogenic shock. The patient who does the best with an LVAD is the one who is [relatively] healthy when implanted, but the patient who needs it most is the one who is literally dying."

"Everyone knows that if you take patients who are sicker [for LVADs], you’ll have trouble reaching 80% survival after 2 years. But there is not yet enough confidence in the treatment to extend it to INTERMACS level 4, 5, or 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "That’s where the big potential is. The action currently is in INTERMACS 2 and 3. For patients who are INTERMACS 3, there is no question that if they can’t get a transplant they need a VAD. The sweet spot will be patients at INTERMACS 4."

The INTERMACS registry numbers show that the field is currently stuck when it comes to INTERMACS levels, with the greatest number of LVADs going into level 2 patients, who received 34% of U.S LVADS during January-March 2012. The 34% level in early 2012 was down from 38% of LVAD recipients in 2011 and 47% in 2010, but growth in less-severe levels has been slow. At the start of 2012, 30% of LVAD recipients were at level 3, a small increase from the 27% rate in 2011 and 2010. Level 4 patients constituted 14% of LVAD recipients in early 2012, essentially unchanged from the prior 2 years, and level 5, 6, or 7 patients have consistently been a small slice of the U.S. LVAD pie, roughly 5% of recipients each year.

Beyond the INTERMACS Level

Heart failure specialists now recognize that INTERMACS level tells just part of the story.

"INTERMACS profiles depend on heart failure symptoms but not comorbidities. Severe diabetes, obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiorenal syndrome, chronic malnourishment, morbid obesity, and other factors all fall outside the INTERMACS profile criteria," said Dr. Kirklin.

He and his associates are formulating a risk assessment equation that will take comorbidities into account for a more global patient assessment. The most recently published INTERMACS registry analysis, which he first authored using data through the end of June 2011 with a total of 4,366 patients who received left ventricular support since 2006 (J. Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:117-26), identified several comorbidity markers that each significantly linked with increased mortality. For example, a 1-unit increase in bilirubin linked with a 10% boost in mortality, a 1-unit increase in creatinine raised mortality by 16%, and a 0.5-unit increase in body surface area linked with a 48% rise in deaths. One of the strongest risk factors was being at INTERMACS level 1, which linked with a more-than-threefold higher mortality rate.

But more work must be done before the risk assessment formula is ready for clinical use. Right now, the formula "is not very reliable yet, because the maximum patient follow-up is 2 years. We need a little more follow-up," Dr. Kirklin said.

Growing the LVAD Numbers

Further growth in LVAD placements will happen on two fronts: broader use in patients at INTERMACS levels 2 and 3, and possibly level 4, where a strong consensus exists for LVAD support; and new evidence to document efficacy and safety in patients with less-severe disease at INTERMACS levels 4, 5, 6, and 7.

For the existing population, it’s a matter of physician and patient awareness. "We need to educate physicians that this is an option," said Dr. Lanfear. "Awareness is lacking. There is a lot of heart failure out there that is underrecognized and underreferred. Neither patients nor their physicians realize how sick they are, and that they are at a high enough risk to justify this."

Furthermore, there are parts of the country where the technology is underused. "In areas without a big center nearby, some physicians may not recognize patients who are sick enough to be LVAD candidates. We are trying to spread the word on who these patients are and when they should be referred."

According to Dr. Teuteberg, major warning signs that should flag patients who are potential LVAD candidates include advanced symptoms, increasing numbers of hospitalizations for heart failure, dwindling responses to ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers, increasing dosages of diuretics, a persistently high serum level of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) despite good medical treatment, and lack of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Expansion of the evidence base to show LVAD benefits in patients with INTERMACS level 5, 6, or 7 disease depends on a trial just starting, the REVIVE-IT (Randomized Evaluation of VAD Intervention Before Inotropic Therapy) study that’s set to enroll about 100 patients. But at press time, REVIVE-IT had not yet begun, posing doubts about LVAD use in the study’s targeted patients. "We haven’t really demonstrated reproducibly good survival [with LVADs] to compete with medical therapy in level 5 and 6 patients," said Dr. Kirklin. "The FDA put the study on hold while they reflected on that."

Making LVADs Better

With fast-paced technological advancement, continuous-flow LVADs will continue to evolve and improve. In June, results appeared on a new continuous-flow LVAD, the HeartWare device (Circulation 2012;125:3191-200), and last April an FDA advisory committee recommended that the agency approve the HeartWare LVAD for use as a bridge to (a trial testing the HeartWare LVAD for destination therapy is ongoing).

But no one interviewed for this article anticipates that the HeartWare LVAD will be a major advance. "Fundamentally, the major components and the implant technique are the same for the two devices," the HeartWare and the HeartMate II, said Dr. Slaughter. The HeartWare LVAD is smaller and designed to be placed completely in the pericardial space, but any clinical advantages based on these differences remain to be proved, he said in an interview.

A more meaningful improvement in LVAD design is in the works, and may reach initial clinical testing within a couple of years: a fully implantable LVAD with no transcutaneous drive line, a part that is subject to infection, prevents patients from submerging, and physically and psychologically limits patients by tethering them to equipment. "If there were one thing that could make a dramatic difference, it would be getting rid of the drive line. That is the Holy Grail for the field," said Dr. Bailey.

When a fully implantable LVAD becomes available for routine use, it will complete the LVAD revolution and help device therapy for advanced heart failure reach its full potential.

Dr. Lanfear has received research support and has received honoraria as a speaker for Thoratec, the company that markets the HeartMate II, and has received research support from HeartWare, the company developing the HeartWare LVAD. Dr. Slaughter has had contracts for services to Thoratec and HeartWare. Dr. Kirklin, Dr. Bailey, Dr. Teuteberg, and Dr. Taylor said that they had no disclosures.

*CORRECTION 8/10/12: The credit for the photo with the caption "The next LVAD in line, HeartWare, is smaller and dwells in the pericardial space" was misstated and should have been ©2012 HeartWare International, Inc.