User login

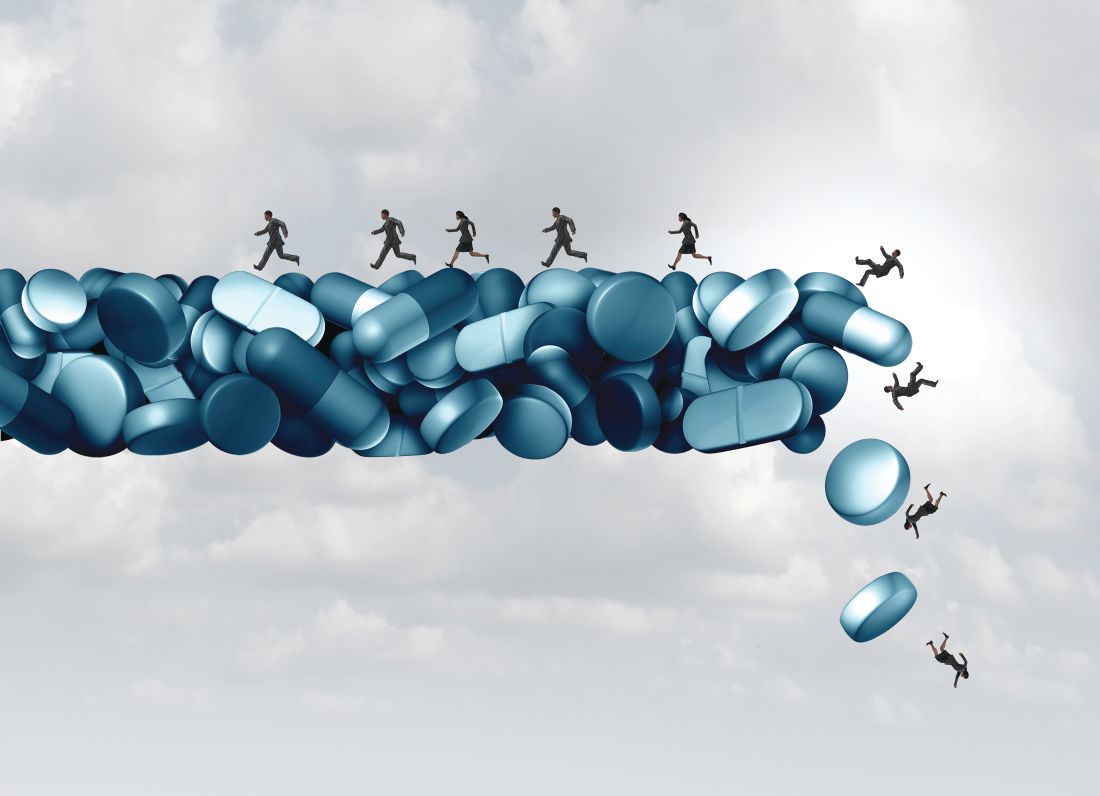

Barry Schultz, MD, once operated a thriving pain clinic in Delray Beach, Fla. Now he is serving a 157-year prison sentence after a conviction of selling opioids on a massive scale.

In an interview with Bill Whitaker of “60 Minutes,” Dr. Schultz explains: “I’m a scapegoat. I mean, I was one of hundreds of doctors that were prescribing medication for chronic pain. I see myself as a healer. … In my mind, what I was doing was legitimate.”

This role included prescribing more than 1,000 opioid pills to a woman during her pregnancy. She and thousands of others sought drugs from Dr. Schultz, who complied. In 2010, he prescribed nearly 17,000 of the highest-potency oxycodone pills to one patient over 7 months. Another patient was prescribed more than 23,000 pills over 8 months – more than 100 pills a day.

In 2009, more than 2,900 people died in Florida of drug overdoses, mostly from prescribed opioid pills. “In one 16-month period, Dr. Schultz dispensed 800,000 opioid pills from his office pharmacy,” the report says. The massive prescribing spree netted Dr. Schultz more than $6,000 a day, “60 Minutes” reported.

“When I started treating people with chronic noncancer pain, I felt it was unethical and discriminatory to limit the dose of medication. And if I had known that the overdose incidents had increased dramatically the way it had, I would have moderated my approach,” he says in the interview.

According to Mr. Whitaker,

Medicine and empathy

For years, actor Alan Alda was TV’s favorite doctor. His 11-season stint as Dr. Hawkeye Pierce on MASH garnered him critical acclaim for his portrayal of the empathetic side of being a physician and human in trying circumstances. In his post-MASH life, Mr. Alda has rechanneled his TV persona and become a spokesperson for the power of empathy for health care professionals and scientists – and anyone who can benefit from better communication.

In a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation interview with Brian Goldman, MD, of “White Coat, Black Art,” Mr. Alda explains that “empathic behavior is medicine.” He cites an example of a physician who had to let a patient know of her cancer diagnosis. “[The doctor] went in and he sat across from her at her level. Took her hand in his hand and talked in very plain language. Didn’t use the word ‘metastasis.’ And, for the first time, she reacted. ... And, for the first time, she asked a question. He came back to us and said: ‘It was just like the mirroring exercise. I was helping her face death, and she was helping me be a better doctor.’ ”

The mirroring exercise he refers to is a part of a workshop Mr. Alda conducts at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in New York. The program, which focuses on the role of human connection and communication, has proven popular – and is now taught at 17 medical schools and universities worldwide.

Mr. Alda has proven to be an apt teacher. Now he is a patient, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 3 years ago. Only recently did he decide it was time to let everyone in on the news.

“The main reason that I made a statement about it publicly was that … I didn’t want the story to come out in a maudlin way. If somebody saw me, saw my tremor on television then somebody might write an article about isn’t it sad and terrible and awful,” Mr. Alda says.

“I mean [Parkinson’s disease] is not a good thing to have. There’s no doubt about that. But there’s a stigma associated with it which is not helpful to people. And that is as soon as you know you have it, as soon as you get a diagnosis that’s the end of everything, and it’s not.”

Claire Foy’s life with anxiety

Another star of stage and screen has opened up about her troubles. In an interview with freelance writer Tom Lamont for The Guardian, actress Claire Foy explains her struggles with anxiety.

Her condition is not new. Now 34, she has experienced anxiety since childhood. Despite the acclaim and awards, she says she has been plagued by self-doubt and negative thoughts and underestimated her ability. “When you have anxiety, you have anxiety about – I don’t know – crossing the road,” she explains.

But the spotlight that has come with bravura performances, such as her turn as Queen Elizabeth II in the Netflix series “The Crown” and as the antihero Lisbeth Salander in soon-to-be-released “The Girl in the Spider’s Web,” ratcheted up her anxiety.

“The thing about it is, it’s not related to anything that would seem logical. It’s purely about that feeling in the pit of your stomach, and the feeling that you can’t, because you’re ‘this’ or you’re ‘that.’ It’s my mind working at a thousand beats a second and running away with a thought.”

She is currently on hiatus; daily life right now revolves around her daughter. Anxiety remains a part of the day, although time and therapy are easing the burden. “It’s still there, but I guess I don’t believe it so much anymore. I used to think that this was my lot in life, to be anxious,” she said in the interview. “And that I would struggle and struggle and struggle with it, and that it would make me quite miserable, and that I’d always be restricted.”

“But now I’m able to disassociate myself from it more. I know that it’s just something I have – and that I can take care of myself.”

Padma Lakshmi speaks out about rape

Author, cook, TV host, and producer Padma Lakshmi is another celebrity with a seemingly glittering life. But, like Mr. Alda and Ms. Foy, there is darkness. In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times and as reported by Maura Hohman of People magazine, she described being raped at age 16 by her then-boyfriend.

“When we went out, he would park the car and come in and sit on our couch and talk to my mother. He never brought me home late on a school night. We were intimate to a point, but he knew that I was a virgin and that I was unsure of when I would be ready to have sex,” Ms. Lakshmi explains.

“On New Year’s Eve, just a few months after we first started dating, he raped me.”

Ms. Lakshmi says she felt it was her fault at the time. “We had no language in the 1980s for date rape,” she wrote in the opinion piece. Flash ahead to the present and she understands well the current climate around this #WhyIDidn’tReport moment. “I understand why both women would keep this information to themselves for so many years, without involving the police. For years, I did the same thing.”

Her story has inspired victims to come forward with their experiences and, in one case, for an attacker to apologize for his actions.

Are you reading this? Your brain thanks you

For many, reading and thinking deeply can seem a lost pursuit in this ever-changing digital world. But this does not have to be the case, according to cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf, PhD, incoming director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In her book “Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World,” (Harper, 2018) and in an interview with WBUR’s “On Point,” Dr. Wolf describes her unease over her seeming inability to focus on the printed page other than the tendency to grab snippets of detail.

“At some time impossible to pinpoint, I had begun to read more to be informed than to be immersed, much less to be transported,” she says.

Pondering this led her to realize that she was still up to the mental task of reading but was not devoting as much time to it. She set aside time each day to revisit a novel that she had found daunting reading in her youth, “Magister Ludi” by Hermann Hesse. The novel still proved to be slow going. But optimistically, the experiment made clear to Dr. Wolf that she had “changed in ways I would never have predicted. I now read on the surface and very quickly; in fact, I read too fast to comprehend deeper levels, which forced me constantly to go back and reread the same sentence over and over with increasing frustration.”

The culprit, she concludes, was the instant world of the Internet. Her brain had become used to dabbling in information. In the absence of cognitive impediments, she says, what was lacking in brainpower could be restored. To Dr. Wolf and others who fret over the difficulty in the pleasure of relaxing with a book, there is comfort in knowing that, with some literary exercise, the brain can shift from the digital world to the less frenetic world of the printed page.

Barry Schultz, MD, once operated a thriving pain clinic in Delray Beach, Fla. Now he is serving a 157-year prison sentence after a conviction of selling opioids on a massive scale.

In an interview with Bill Whitaker of “60 Minutes,” Dr. Schultz explains: “I’m a scapegoat. I mean, I was one of hundreds of doctors that were prescribing medication for chronic pain. I see myself as a healer. … In my mind, what I was doing was legitimate.”

This role included prescribing more than 1,000 opioid pills to a woman during her pregnancy. She and thousands of others sought drugs from Dr. Schultz, who complied. In 2010, he prescribed nearly 17,000 of the highest-potency oxycodone pills to one patient over 7 months. Another patient was prescribed more than 23,000 pills over 8 months – more than 100 pills a day.

In 2009, more than 2,900 people died in Florida of drug overdoses, mostly from prescribed opioid pills. “In one 16-month period, Dr. Schultz dispensed 800,000 opioid pills from his office pharmacy,” the report says. The massive prescribing spree netted Dr. Schultz more than $6,000 a day, “60 Minutes” reported.

“When I started treating people with chronic noncancer pain, I felt it was unethical and discriminatory to limit the dose of medication. And if I had known that the overdose incidents had increased dramatically the way it had, I would have moderated my approach,” he says in the interview.

According to Mr. Whitaker,

Medicine and empathy

For years, actor Alan Alda was TV’s favorite doctor. His 11-season stint as Dr. Hawkeye Pierce on MASH garnered him critical acclaim for his portrayal of the empathetic side of being a physician and human in trying circumstances. In his post-MASH life, Mr. Alda has rechanneled his TV persona and become a spokesperson for the power of empathy for health care professionals and scientists – and anyone who can benefit from better communication.

In a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation interview with Brian Goldman, MD, of “White Coat, Black Art,” Mr. Alda explains that “empathic behavior is medicine.” He cites an example of a physician who had to let a patient know of her cancer diagnosis. “[The doctor] went in and he sat across from her at her level. Took her hand in his hand and talked in very plain language. Didn’t use the word ‘metastasis.’ And, for the first time, she reacted. ... And, for the first time, she asked a question. He came back to us and said: ‘It was just like the mirroring exercise. I was helping her face death, and she was helping me be a better doctor.’ ”

The mirroring exercise he refers to is a part of a workshop Mr. Alda conducts at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in New York. The program, which focuses on the role of human connection and communication, has proven popular – and is now taught at 17 medical schools and universities worldwide.

Mr. Alda has proven to be an apt teacher. Now he is a patient, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 3 years ago. Only recently did he decide it was time to let everyone in on the news.

“The main reason that I made a statement about it publicly was that … I didn’t want the story to come out in a maudlin way. If somebody saw me, saw my tremor on television then somebody might write an article about isn’t it sad and terrible and awful,” Mr. Alda says.

“I mean [Parkinson’s disease] is not a good thing to have. There’s no doubt about that. But there’s a stigma associated with it which is not helpful to people. And that is as soon as you know you have it, as soon as you get a diagnosis that’s the end of everything, and it’s not.”

Claire Foy’s life with anxiety

Another star of stage and screen has opened up about her troubles. In an interview with freelance writer Tom Lamont for The Guardian, actress Claire Foy explains her struggles with anxiety.

Her condition is not new. Now 34, she has experienced anxiety since childhood. Despite the acclaim and awards, she says she has been plagued by self-doubt and negative thoughts and underestimated her ability. “When you have anxiety, you have anxiety about – I don’t know – crossing the road,” she explains.

But the spotlight that has come with bravura performances, such as her turn as Queen Elizabeth II in the Netflix series “The Crown” and as the antihero Lisbeth Salander in soon-to-be-released “The Girl in the Spider’s Web,” ratcheted up her anxiety.

“The thing about it is, it’s not related to anything that would seem logical. It’s purely about that feeling in the pit of your stomach, and the feeling that you can’t, because you’re ‘this’ or you’re ‘that.’ It’s my mind working at a thousand beats a second and running away with a thought.”

She is currently on hiatus; daily life right now revolves around her daughter. Anxiety remains a part of the day, although time and therapy are easing the burden. “It’s still there, but I guess I don’t believe it so much anymore. I used to think that this was my lot in life, to be anxious,” she said in the interview. “And that I would struggle and struggle and struggle with it, and that it would make me quite miserable, and that I’d always be restricted.”

“But now I’m able to disassociate myself from it more. I know that it’s just something I have – and that I can take care of myself.”

Padma Lakshmi speaks out about rape

Author, cook, TV host, and producer Padma Lakshmi is another celebrity with a seemingly glittering life. But, like Mr. Alda and Ms. Foy, there is darkness. In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times and as reported by Maura Hohman of People magazine, she described being raped at age 16 by her then-boyfriend.

“When we went out, he would park the car and come in and sit on our couch and talk to my mother. He never brought me home late on a school night. We were intimate to a point, but he knew that I was a virgin and that I was unsure of when I would be ready to have sex,” Ms. Lakshmi explains.

“On New Year’s Eve, just a few months after we first started dating, he raped me.”

Ms. Lakshmi says she felt it was her fault at the time. “We had no language in the 1980s for date rape,” she wrote in the opinion piece. Flash ahead to the present and she understands well the current climate around this #WhyIDidn’tReport moment. “I understand why both women would keep this information to themselves for so many years, without involving the police. For years, I did the same thing.”

Her story has inspired victims to come forward with their experiences and, in one case, for an attacker to apologize for his actions.

Are you reading this? Your brain thanks you

For many, reading and thinking deeply can seem a lost pursuit in this ever-changing digital world. But this does not have to be the case, according to cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf, PhD, incoming director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In her book “Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World,” (Harper, 2018) and in an interview with WBUR’s “On Point,” Dr. Wolf describes her unease over her seeming inability to focus on the printed page other than the tendency to grab snippets of detail.

“At some time impossible to pinpoint, I had begun to read more to be informed than to be immersed, much less to be transported,” she says.

Pondering this led her to realize that she was still up to the mental task of reading but was not devoting as much time to it. She set aside time each day to revisit a novel that she had found daunting reading in her youth, “Magister Ludi” by Hermann Hesse. The novel still proved to be slow going. But optimistically, the experiment made clear to Dr. Wolf that she had “changed in ways I would never have predicted. I now read on the surface and very quickly; in fact, I read too fast to comprehend deeper levels, which forced me constantly to go back and reread the same sentence over and over with increasing frustration.”

The culprit, she concludes, was the instant world of the Internet. Her brain had become used to dabbling in information. In the absence of cognitive impediments, she says, what was lacking in brainpower could be restored. To Dr. Wolf and others who fret over the difficulty in the pleasure of relaxing with a book, there is comfort in knowing that, with some literary exercise, the brain can shift from the digital world to the less frenetic world of the printed page.

Barry Schultz, MD, once operated a thriving pain clinic in Delray Beach, Fla. Now he is serving a 157-year prison sentence after a conviction of selling opioids on a massive scale.

In an interview with Bill Whitaker of “60 Minutes,” Dr. Schultz explains: “I’m a scapegoat. I mean, I was one of hundreds of doctors that were prescribing medication for chronic pain. I see myself as a healer. … In my mind, what I was doing was legitimate.”

This role included prescribing more than 1,000 opioid pills to a woman during her pregnancy. She and thousands of others sought drugs from Dr. Schultz, who complied. In 2010, he prescribed nearly 17,000 of the highest-potency oxycodone pills to one patient over 7 months. Another patient was prescribed more than 23,000 pills over 8 months – more than 100 pills a day.

In 2009, more than 2,900 people died in Florida of drug overdoses, mostly from prescribed opioid pills. “In one 16-month period, Dr. Schultz dispensed 800,000 opioid pills from his office pharmacy,” the report says. The massive prescribing spree netted Dr. Schultz more than $6,000 a day, “60 Minutes” reported.

“When I started treating people with chronic noncancer pain, I felt it was unethical and discriminatory to limit the dose of medication. And if I had known that the overdose incidents had increased dramatically the way it had, I would have moderated my approach,” he says in the interview.

According to Mr. Whitaker,

Medicine and empathy

For years, actor Alan Alda was TV’s favorite doctor. His 11-season stint as Dr. Hawkeye Pierce on MASH garnered him critical acclaim for his portrayal of the empathetic side of being a physician and human in trying circumstances. In his post-MASH life, Mr. Alda has rechanneled his TV persona and become a spokesperson for the power of empathy for health care professionals and scientists – and anyone who can benefit from better communication.

In a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation interview with Brian Goldman, MD, of “White Coat, Black Art,” Mr. Alda explains that “empathic behavior is medicine.” He cites an example of a physician who had to let a patient know of her cancer diagnosis. “[The doctor] went in and he sat across from her at her level. Took her hand in his hand and talked in very plain language. Didn’t use the word ‘metastasis.’ And, for the first time, she reacted. ... And, for the first time, she asked a question. He came back to us and said: ‘It was just like the mirroring exercise. I was helping her face death, and she was helping me be a better doctor.’ ”

The mirroring exercise he refers to is a part of a workshop Mr. Alda conducts at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in New York. The program, which focuses on the role of human connection and communication, has proven popular – and is now taught at 17 medical schools and universities worldwide.

Mr. Alda has proven to be an apt teacher. Now he is a patient, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 3 years ago. Only recently did he decide it was time to let everyone in on the news.

“The main reason that I made a statement about it publicly was that … I didn’t want the story to come out in a maudlin way. If somebody saw me, saw my tremor on television then somebody might write an article about isn’t it sad and terrible and awful,” Mr. Alda says.

“I mean [Parkinson’s disease] is not a good thing to have. There’s no doubt about that. But there’s a stigma associated with it which is not helpful to people. And that is as soon as you know you have it, as soon as you get a diagnosis that’s the end of everything, and it’s not.”

Claire Foy’s life with anxiety

Another star of stage and screen has opened up about her troubles. In an interview with freelance writer Tom Lamont for The Guardian, actress Claire Foy explains her struggles with anxiety.

Her condition is not new. Now 34, she has experienced anxiety since childhood. Despite the acclaim and awards, she says she has been plagued by self-doubt and negative thoughts and underestimated her ability. “When you have anxiety, you have anxiety about – I don’t know – crossing the road,” she explains.

But the spotlight that has come with bravura performances, such as her turn as Queen Elizabeth II in the Netflix series “The Crown” and as the antihero Lisbeth Salander in soon-to-be-released “The Girl in the Spider’s Web,” ratcheted up her anxiety.

“The thing about it is, it’s not related to anything that would seem logical. It’s purely about that feeling in the pit of your stomach, and the feeling that you can’t, because you’re ‘this’ or you’re ‘that.’ It’s my mind working at a thousand beats a second and running away with a thought.”

She is currently on hiatus; daily life right now revolves around her daughter. Anxiety remains a part of the day, although time and therapy are easing the burden. “It’s still there, but I guess I don’t believe it so much anymore. I used to think that this was my lot in life, to be anxious,” she said in the interview. “And that I would struggle and struggle and struggle with it, and that it would make me quite miserable, and that I’d always be restricted.”

“But now I’m able to disassociate myself from it more. I know that it’s just something I have – and that I can take care of myself.”

Padma Lakshmi speaks out about rape

Author, cook, TV host, and producer Padma Lakshmi is another celebrity with a seemingly glittering life. But, like Mr. Alda and Ms. Foy, there is darkness. In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times and as reported by Maura Hohman of People magazine, she described being raped at age 16 by her then-boyfriend.

“When we went out, he would park the car and come in and sit on our couch and talk to my mother. He never brought me home late on a school night. We were intimate to a point, but he knew that I was a virgin and that I was unsure of when I would be ready to have sex,” Ms. Lakshmi explains.

“On New Year’s Eve, just a few months after we first started dating, he raped me.”

Ms. Lakshmi says she felt it was her fault at the time. “We had no language in the 1980s for date rape,” she wrote in the opinion piece. Flash ahead to the present and she understands well the current climate around this #WhyIDidn’tReport moment. “I understand why both women would keep this information to themselves for so many years, without involving the police. For years, I did the same thing.”

Her story has inspired victims to come forward with their experiences and, in one case, for an attacker to apologize for his actions.

Are you reading this? Your brain thanks you

For many, reading and thinking deeply can seem a lost pursuit in this ever-changing digital world. But this does not have to be the case, according to cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf, PhD, incoming director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In her book “Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World,” (Harper, 2018) and in an interview with WBUR’s “On Point,” Dr. Wolf describes her unease over her seeming inability to focus on the printed page other than the tendency to grab snippets of detail.

“At some time impossible to pinpoint, I had begun to read more to be informed than to be immersed, much less to be transported,” she says.

Pondering this led her to realize that she was still up to the mental task of reading but was not devoting as much time to it. She set aside time each day to revisit a novel that she had found daunting reading in her youth, “Magister Ludi” by Hermann Hesse. The novel still proved to be slow going. But optimistically, the experiment made clear to Dr. Wolf that she had “changed in ways I would never have predicted. I now read on the surface and very quickly; in fact, I read too fast to comprehend deeper levels, which forced me constantly to go back and reread the same sentence over and over with increasing frustration.”

The culprit, she concludes, was the instant world of the Internet. Her brain had become used to dabbling in information. In the absence of cognitive impediments, she says, what was lacking in brainpower could be restored. To Dr. Wolf and others who fret over the difficulty in the pleasure of relaxing with a book, there is comfort in knowing that, with some literary exercise, the brain can shift from the digital world to the less frenetic world of the printed page.