User login

CASE Is her request reasonable?

A 40-year-old primigravid woman presents for her first prenatal visit and asks for cesarean delivery. She explains that she has “waited all her life” for this baby and does not want to risk any harm to the infant during childbirth. She also admits that she is uncomfortable with the unpredictability of childbirth.

CASE Don’t try to dissuade her

The best way to handle this 40-year-old woman’s concerns is to avoid trying to change her mind. Instead, try to understand her view, which no doubt influences her experience of pregnancy, and do your best to remain unbiased as you gather information about her beliefs and constructs. Don’t fall into the trap of merely dispensing facts without her input, or the discussion will be unproductive.

When she reveals that other women have told her about their experiences with long labors and emergency cesarean delivery, you have an opening for discussion. Return to her concerns periodically during the course of antenatal care, telling her what to expect during pregnancy and delivery, and lay out the pros and cons of cesarean vs vaginal delivery. Other helpful resources are a second opinion, birthing classes, and prenatal yoga and expectant mothers’ groups. The next choice is up to you. Once she understands the fetal and maternal risks of cesarean delivery and still prefers an elective cesarean, the next choice is up to you. If you are morally opposed to the idea, refer the patient to another physician who would be willing to perform the cesarean delivery.

The patient should also consider how she will want to proceed if she presents in active labor before her scheduled cesarean section.

The request may be reasonable, but it is impossible to know without an extended discussion and an individualized decision.1-11

Requests for cesarean delivery are becoming more common as the cesarean delivery rate hits all-time highs and the media focuses greater attention on the risks inherent in labor and vaginal delivery. One indicator of the increasing incidence of maternal requests for elective cesarean is the recent State of the Science Conference on the subject, convened by the National Institutes of Health, March 27–29, 2006. (See for more on this conference.)

This article describes what considerations should go into the discussion of cesarean delivery on maternal request, including ways of predicting whether vaginal delivery will be successful, the importance of knowing the number of children desired, the need to observe key ethical principles, and the balancing act necessary between physician and patient autonomy.

Gauging the likelihood of safe vaginal delivery

Cesarean on demand, without a clinical indication, may be reasonable in some circumstances, although we lack data to prove that cesarean delivery is globally superior to vaginal delivery in terms of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Scoring systems may help. For example, maternal obesity is a leading risk factor for cesarean delivery, as are short height, advanced maternal age, large pregnancy weight gain, large birth weight, and increasing gestational age.12

Using scoring systems that assign values to these risk factors, one can reasonably predict a patient’s likelihood of undergoing cesarean delivery after attempted vaginal delivery.13,14

Fetal distress remains wild card

Unfortunately, these scoring tools cannot account for the unpredictability of “fetal distress,” which remains, along with shoulder dystocia, one of the main reasons for performing cesarean delivery in labor.15,16

Ethical concerns

The principles that guide medical decision-making and counseling are:

- Respect for autonomy. The patient has a right to refuse or choose recommended treatments.

- Beneficence. The physician is obligated to promote maternal and fetal well-being, and the patient is obligated to promote the well-being of her fetus.

- Nonmaleficence centers on the goal of avoiding harm and complements the principle of beneficence.

- Justice refers to fairness to the individual and physician and the impact on society.4-7

Consider both short- and long-term consequences

Epidemiologically, physicians bear responsibility for the short- and long-term impacts of their actions. For example, injudicious prescribing of antibiotics has led to drug resistance, and many patients now believe they have the right to request antibiotics for likely viral illness. In obstetrics, the lack of emphasis or counseling on breastfeeding created a cascade effect, which started with affluent women who rejected breastfeeding and eventually reached all socioeconomic groups.

TABLE

Maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality rates for planned vaginal and elective cesarean deliveries

| ADVERSE OUTCOMES | |

|---|---|

| PLANNED VAGINAL DELIVERY | ELECTIVE CESAREAN |

| FETAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:3,400. All low-risk attempted vaginal deliveries, including those resulting in intrapartum cesarean delivery | Mortality None (n=1,048 low-risk parturients)‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Shoulder dystocia | Transient mild respiratory acidosis |

| Intrauterine hypoxia* | Laceration |

| Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull | Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull32 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage 1:1,900 | Intracranial hemorrhage 1:2,050 |

| Facial nerve injury 1:3,030 | Facial nerve injury 1:2,040† |

| Brachial plexus injury 1:1,300† | Brachial plexus injury 1:2,400 |

| Convulsions 1:1,560 | Convulsions 1:1,160† |

| CNS depression 1:3,230 | CNS depression 1:1,500† |

| Feeding difficulty 1:150 | Feeding difficulty 1:90† |

| Mechanical ventilation 1:390 | Mechanical ventilation 1:140† |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:1,240 | Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:270† |

| Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:90 | Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:30† |

| Respiratory distress syndrome 1:640 | Respiratory distress syndrome 1:470† |

| MATERNAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:8,570 | Mortality 1:2,131‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Urinary incontinence | Endometritis |

| Fecal/flatulence (rectal) incontinence | Wound infection |

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage |

| Deep venous thrombosis | Pelvic infection |

| Subjectively decreased vaginal tone | Deep venous thrombosis |

| Dyspareunia | Delayed breastfeeding/holding neonate |

| Latex allergy | |

| Endometriosis | |

| Adenomyosis | |

| Gallbladder disease | |

| Appendicitis | |

| lleus | |

| Operative complications (ureteral, GI injury) | |

| Scar tissue formation | |

| Controversial | |

| After 3 elective cesarean deliveries, minimal to no protection from urinary incontinence | |

| After menopause and visceroptosis from advancing age, many elderly, regardless of parity or mode of delivery, will have some incontinence25 | |

| * Increased cesarean delivery rate has not decreased incidence of cerebral palsy.33 | |

| † Statistical significance. | |

| ‡ Neonatal and infant mortality in Brazil has decreased with increasing frequency of elective cesarean delivery.34 | |

| SOURCE: Mortality data rounded and adapted from Richardson BS, et al,35 Levine EM, et al,36 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 Morbidity data rounded and adapted from Towner D, et al,38 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 | |

Will poorer women have equal access?

Women in lower socioeconomic groups should not receive substandard care; however, the inverse care “law” describes a disturbing reality: The availability of good medical care is inversely related to the need of the population served.17,18 Thus, the concept of justice, or taking into consideration the greater good for society, is relevant to the elective cesarean debate.

Costs and complications

Cost analysis has shown that expenditures are minimally increased by elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks’ gestation, which also involves more efficient and predictable use of staffing resources.19

Parallel placenta accreta rate

The risk of morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancies exceeding 39 weeks’ gestation may be reduced.1 However, the 10-fold increase in placenta accreta over the past 50 years parallels the rise in cesarean deliveries.20

Fundamentals of patient counseling

Lay out benefits and risks

A detailed comparison of the relative benefits and risks of cesarean delivery (elective, intrapartum, and emergent) versus vaginal delivery (spontaneous, operative, and failed operative) is warranted, along with exploration of the patient’s fears and pressures.1-10,16

Unfortunately, trials comparing all these modes of delivery and all possible adverse outcomes are lacking. (A brief summary of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes is given in TABLE.) Operative vaginal delivery and intrapartum cesarean delivery generally do increase the risk of injury to maternal pelvic structures, as well as the risk of shoulder dystocia and fetal intracranial hemorrhage.

It is important to remain as unbiased as possible when counseling a patient, and to try to balance the conflict between your own autonomy and hers. Acting as a fiduciary for the patient should not involve suppressing your own sound medical judgment. Nor does it remove the patient’s responsibility to remain involved in her care.1-8

Although the patient’s right to refuse treatment is usually considered absolute, she can be prevented from demanding intervention when such intervention is not medically supported.2,4-6,21

Don’t forget future risks

Patients desiring elective cesarean delivery should be apprised of the complications that can arise in subsequent pregnancies.

Some women choose elective cesarean delivery to avoid the hazards of a trial of labor, but may not realize additional hazards, such as placenta accreta, can arise in pregnancies after a cesarean.

Although most women choosing to have only 2 children may experience no complications from elective primary and elective repeat cesarean delivery, some run the risk of placenta previa and possible accreta during the second gestation. These women may experience severe bleeding and require preterm repeat cesarean delivery with hysterectomy. Thus, it is vital to take the patient’s reproductive goals into consideration.

Fear of urinary and rectal incontinence is another reason women often give for desiring cesarean rather than vaginal delivery. However, Rortveit and colleagues22 demonstrated that incontinence affects most elderly women regardless of parity. In addition, it is possible that pregnancy itself contributes to pelvic organ prolapse.10,23,24

Be open to a second opinion

After counseling the patient about risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery, raise the issue of a second opinion, and offer the appropriate referrals if one is desired.4-8,25

ObGyns and patients answer emphatically

BREAKING NEWS

OBG Management Senior, Editor Janelle Yates covered the NIH, Conference March 27–29, 2006 in Bethesda, MD., The panel’s draft statement is available online at http://consensus.nih.gov The final statement is expected this month.

Passions ran high at the NIH State of the Science Conference on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request, last month. On one side were the 17 panel members and Chair Mary E. D’Alton, MD, of Columbia University, who were charged with reviewing the data and responding to questions and comments from audience members—many of whom adamantly opposed patient-choice cesarean.

On the other side were audience members themselves: a mix of physicians, researchers, nurses, nurse-midwives, and the media.

At issue was whether patient choice even exists in obstetrics or is merely a byproduct of physicians’ unwitting influence over their patients.

“My doctor said it, so I did it”

Susan Dentzer, health correspondent for The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, posed the question: “When is a request not really a request but a kind of going along with the moment, often with the provider’s strong preference, and electing the best of the options as they are presented to you at a particular point in time?”

Dentzer, a veteran of elective cesarean, had been invited to speak on the patient’s perspective. She later quipped: “Here’s my complicated decision-making process: My doctor said it, so I did it.”

One ObGyn’s perspective

Millie Sullivan Nelson, head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Christie Clinic in Champaign, Illinois, offered the general obstetrician’s point of view, zeroing in on the high-tech way of giving birth in the 21st century. Over the past 15 years, there has been “a subtle infusion of technology into obstetrics, the goal being to improve the quality of birth outcomes,” she said. “Today’s women may have up to 16 different tubes, drugs, or attachments during their labor process. No wonder some women choose cesarean delivery.”

Dr. Nelson offered a straightforward and engaging recitation of her family history to illustrate the dramatic changes in the typical childbirth experience over the past century. She noted that her maternal grandmother, born in 1895, suffered from rickets, yet beat the odds by giving birth to 4 children—all via cesarean section with vertical incisions. Dr. Nelson’s mother, born in 1926, had 12 children by spontaneous vaginal delivery—5 of them breech presentations. All 12 deliveries took place in “an era of minimal intervention,” she observed.

Dr. Nelson herself had 4 vaginal deliveries. “All of my deliveries were induced to facilitate my personal professional life and that of my obstetrician, who was my partner,” she said. In contrast to her mother and grandmother, who labored and delivered in 2 different rooms, Dr. Nelson had continuous fetal monitoring, her family at her bedside, and delivery in the same room where her labors took place. All 4 deliveries were videotaped.

Too posh to push?

“Now what about today’s woman?” Dr. Nelson asked, choosing pop idol Britney Spears as an example. When Spears chose primary cesarean as her preferred method of delivery, the tabloids accused her of being “too posh to push.”

Despite the furor in some quarters, Dr. Nelson believes times have changed. “My personal opinion is that there has been a gradual acceptance of cesarean section as an option for women, both on the part of the patient and the physician.”

Insurers still behind the curve

Another force shaping the debate is the insurance industry, Dr. Nelson noted. “In my community, precertification of all electively scheduled cesarean sections is required.” When a patient recently asked for cesarean delivery—she was 4 foot 11 and estimated fetal weight was 4,000 g—the insurer refused. The outcome: The woman had “first-stage arrest of labor and descent and ultimately went to cesarean section after 18 hours of labor.”

Litigation for unnecessary cesarean?

Dr. Nelson brought up one of the most influential factors in the cesarean-on-demand debate—the threat of lawsuits: “To my knowledge, there is no history of litigation for unnecessary cesarean section,” she said. “My patient is a consumer of services; I am the supplier of that service. It is a win-lose situation. She expects no pain and suffering and an outcome with zero tolerance for error. She demands 6-sigma quality—and when things go wrong she holds me responsible.”

Attention creates demand

Some attendees were frustrated by the increasing focus on cesarean delivery in general, claiming it raises the profile of cesarean section even further. Better to turn attention to ways of improving vaginal delivery, said Wendy Ponte of Mothering magazine. “When does the NIH plan to hold a similar state-of-the-science conference on optimal vaginal birth practices?”

THE PANEL’S FINDINGS

- Not enough data. There is insufficient evidence “to fully evaluate the benefits and risks of cesarean delivery by maternal request as compared to planned vaginal delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton. Therefore, “any decision to perform a cesarean delivery on maternal request should be carefully individualized and consistent with ethical principles.”

- Not for women wanting large families. “Given that the risks of placenta previa and accreta rise with each cesarean delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton, “cesarean delivery by maternal request is not recommended for women desiring several children.”

- Not before 39 weeks. The increased incidence of respiratory morbidity in term and near-term infants delivered via C-section, “has been well documented in the literature and accounts for a significant number of admissions to intensive care units worldwide,” according to presenter Lucky Jain, MD, MBA, from the Emory University Department of Pediatrics. The panel’s conclusion: “Cesarean delivery by maternal request should not be performed prior to 39 weeks or without verification of lung maturity because of the significant danger of neonatal respiratory complications.”

- Pain of childbirth should not be an issue. Women should be offered adequate analgesia during vaginal delivery so that avoidance of pain is not a reason for requesting cesarean delivery.

- Let the patient raise the subject. The patient should be the one to raise the issue of cesarean delivery by maternal request. “We do not believe it should be brought up by the provider to the patient,” said Dr. D’Alton, adding that, when the patient raises the subject, “a discussion should take place.”

- Forget the notion of a target rate. As panel member Michael Brunskill Bracken, PhD, MPH, of Yale University, explained: “The position that the panel has taken is that rather than create an artificial number, we should concentrate on having modes of delivery that are optimal for the mother and child. And if we can achieve that, then the total C-section rate will be whatever it is, but it will reflect optimal C-sections within a particular population.”

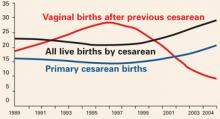

The cesarean delivery rate in the US reached an acme in 2004 at 29.1% of all deliveries. Both the total cesarean rate and the primary cesarean rate have increased each year since 1996. Primary cesarean delivery accounted for 20.6% of all deliveries in 2004—a 40% rise over a decade.12,26

More cesareans, fewer VBACs

Vaginal birth after cesarean has declined from 28.3% to 9.2% since 1996.26 In 2004, 91% of women with 1 cesarean delivery were likely to have repeat cesarean in subsequent deliveries.27

Trend is up in other countries, too

Most developed countries are also seeing increasing cesarean delivery rates. For example, in the United Kingdom, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23% in 2003–2004, up from 17% in 1996–1997.28 In New South Wales, Australia, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23.5% in 2001, up from 17.6% in 1996.29 Data from other countries are older, but typically show increases.

Older “no-risk” gravidas—44% more c-sections For age 35 and older, primiparous women with “no indicated risk” had the greatest frequency of cesarean, according to 1991–2001 US birth certificate data30: 44.2% in 2001—a 44% rise in 10 years.

US trend in cesarean rates per 100 live births

Data for 2003–2004 are preliminary. Due to changes in data collection from implementation of the 2003 revision of the US Standard Certificate of Live Birth, there may be small discontinuities in primary cesarean delivery and VBAC rates in 2003–2004.

SOURCE: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality27

For all ages, primiparous women with no indicated risk had a cesarean delivery rate of 5.5%—a 68% increase in 10 years.

A study from Scotland did report the cesarean delivery rate specifically for “maternal request”: 7.7% in the late 1990s.31

1. Paterson-Brown S. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Yes, as long as the woman is fully informed. BMJ. 1998;317:462-463.

2. Amu O, Rajendran S, Bolaji II. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Maternal choice alone should not determine method of delivery. BMJ. 1998;317:463-465.

3. Norwitz ER. Patient choice cesarean delivery. Available at: http://www.UpToDate.com. Accessed July 7, 2005.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgery and patient choice: the ethics of decision making. Committee Opinion No. 289.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2003.

5. Minkoff H, Chervenak FA. Elective primary cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:946-950.

6. Minkoff H, Powderly KR, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Ethical dimensions of elective primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:387-392.

7. Sharma G, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Minkoff H. Ethical considerations in elective cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:404-408.

8. Bewley S, Cockburn J, II. The unfacts of ’request’ caesarean section. BJOG. 2002;109:597-605.

9. Hohlfeld P. Cesarean section on request: a case for common sense. Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2002;42:19-21.

10. Wagner M. Choosing caesarean section. Lancet. 2000;356:1677-1680.

11. Nygaard I, Cruikshank DP. Should all women be offered elective cesarean delivery? Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:217-219.

12. Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Sutton PD. Preliminary births for 2004. Health E-stats. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. Released October 28, 2005. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelim_bir ths/prelim_births04.htm. Accessed April 4, 2006.

13. Chen G, Uryasev S, Young TK. On prediction of the cesarean delivery risk in a large private practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:616-624.

14. Smith GC, Dellens M, White IR, Pell JP. Combined logistic and Bayesian modeling of cesarean section risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:2029-2034.

15. Liston WA. Rising caesarean section rates: can evolution and ecology explain some of the difficulties of modern childbirth? J R Soc Med. 2003;95:559-561.

16. Anderson GM. Making sense of rising caesarean section rates. BMJ. 2004;329:696-697.

17. Johanson RB, El-Timini S, Rigby C, Young P, Jones P. Caesarean section by choice could fulfill the inverse care law. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:20-22.

18. Belizan JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ. 1999;319:1397-1400.

19. Bost BW. Cesarean delivery on demand: what will it cost? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1418-1423.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Placenta accreta. Committee Opinion No. 266.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2002.

21. Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Inadequacies with the ACOG and AAP statements on managing ethical conflict during the intrapartum period. J Clin Ethics. 1991;2:23-24.

22. Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S. Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:900-907.

23. Dietz HP, Bennett MJ. The effect of childbirth on pelvic organ mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:223-228.

24. Lal M. Prevention of urinary and anal incontinence: role of elective cesarean delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:439-448.

25. Belizan JM, Villar J, Alexander S, et al. Latin American Caesarean Section Study Group. Mandatory second opinion to reduce rates of unnecessary caesarean sections in Latin America: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1934-1940.

26. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2005;54(2):15-17.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_02.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2006.

27. Viswanathan M, Visco AG, Hartmann K, et al. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 133. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2006. AHRQ publication 06–E009.

28. Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. NHS maternity statistics, England 2003–04 [Web page]. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/56/03/04115603.xls. Accessed April 6, 2006.

29. Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health. New South Wales. Mothers and babies 2001. N S W Public Health Bull. 2002;13(S–4). Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/public-health/mdc/mdcrep01.html. Accessed April 10, 2006.

30. Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman MF. Rise in “no indicated risk” primary cesareans in the United States, 1991–2001: cross-sectional analysis. BMJ. 2005;330:71-72.

31. Wilkinson C, Mcllwaine G, Boulton-Jones C, et al. Is a rising caesarean section rate inevitable? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:45-52.

32. Dupuis O, Silveira R, Dupont C, Mottolese C, Kahn P, Dittmar A, Rudigoz R. Comparison of instrument-associated and spontaneous obstetric depressed skull fractures in a cohort of 68 neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:165-170.

33. Wax JR, Cartin A, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Patient choice cesarean: an evidence-based review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:601-616.

34. Groom K, Brown SP. Caesarean section controversy. The rate of caesarean sections is not the issue. BMJ. 2000;320:1072-1073; author reply 1074.

35. Richardson BS, Czikk MJ, daSilva O, Natale R. The impact of labor at term on measures of neonatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:219-226.

36. Levine EM, Ghai V, Barton JJ, Strom CM. Mode of delivery and risk of respiratory diseases in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;439-442.

37. Lilford RJ, van Coeverden de Groot HA, Moore PJ, Bingham P. The relative risks of caesarean section (intrapartum and elective) and vaginal delivery: a detailed analysis to exclude the effects of medical disorders and other acute pre-existing physiological disturbances. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:883-892.

38. Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1709-1714.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Is her request reasonable?

A 40-year-old primigravid woman presents for her first prenatal visit and asks for cesarean delivery. She explains that she has “waited all her life” for this baby and does not want to risk any harm to the infant during childbirth. She also admits that she is uncomfortable with the unpredictability of childbirth.

CASE Don’t try to dissuade her

The best way to handle this 40-year-old woman’s concerns is to avoid trying to change her mind. Instead, try to understand her view, which no doubt influences her experience of pregnancy, and do your best to remain unbiased as you gather information about her beliefs and constructs. Don’t fall into the trap of merely dispensing facts without her input, or the discussion will be unproductive.

When she reveals that other women have told her about their experiences with long labors and emergency cesarean delivery, you have an opening for discussion. Return to her concerns periodically during the course of antenatal care, telling her what to expect during pregnancy and delivery, and lay out the pros and cons of cesarean vs vaginal delivery. Other helpful resources are a second opinion, birthing classes, and prenatal yoga and expectant mothers’ groups. The next choice is up to you. Once she understands the fetal and maternal risks of cesarean delivery and still prefers an elective cesarean, the next choice is up to you. If you are morally opposed to the idea, refer the patient to another physician who would be willing to perform the cesarean delivery.

The patient should also consider how she will want to proceed if she presents in active labor before her scheduled cesarean section.

The request may be reasonable, but it is impossible to know without an extended discussion and an individualized decision.1-11

Requests for cesarean delivery are becoming more common as the cesarean delivery rate hits all-time highs and the media focuses greater attention on the risks inherent in labor and vaginal delivery. One indicator of the increasing incidence of maternal requests for elective cesarean is the recent State of the Science Conference on the subject, convened by the National Institutes of Health, March 27–29, 2006. (See for more on this conference.)

This article describes what considerations should go into the discussion of cesarean delivery on maternal request, including ways of predicting whether vaginal delivery will be successful, the importance of knowing the number of children desired, the need to observe key ethical principles, and the balancing act necessary between physician and patient autonomy.

Gauging the likelihood of safe vaginal delivery

Cesarean on demand, without a clinical indication, may be reasonable in some circumstances, although we lack data to prove that cesarean delivery is globally superior to vaginal delivery in terms of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Scoring systems may help. For example, maternal obesity is a leading risk factor for cesarean delivery, as are short height, advanced maternal age, large pregnancy weight gain, large birth weight, and increasing gestational age.12

Using scoring systems that assign values to these risk factors, one can reasonably predict a patient’s likelihood of undergoing cesarean delivery after attempted vaginal delivery.13,14

Fetal distress remains wild card

Unfortunately, these scoring tools cannot account for the unpredictability of “fetal distress,” which remains, along with shoulder dystocia, one of the main reasons for performing cesarean delivery in labor.15,16

Ethical concerns

The principles that guide medical decision-making and counseling are:

- Respect for autonomy. The patient has a right to refuse or choose recommended treatments.

- Beneficence. The physician is obligated to promote maternal and fetal well-being, and the patient is obligated to promote the well-being of her fetus.

- Nonmaleficence centers on the goal of avoiding harm and complements the principle of beneficence.

- Justice refers to fairness to the individual and physician and the impact on society.4-7

Consider both short- and long-term consequences

Epidemiologically, physicians bear responsibility for the short- and long-term impacts of their actions. For example, injudicious prescribing of antibiotics has led to drug resistance, and many patients now believe they have the right to request antibiotics for likely viral illness. In obstetrics, the lack of emphasis or counseling on breastfeeding created a cascade effect, which started with affluent women who rejected breastfeeding and eventually reached all socioeconomic groups.

TABLE

Maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality rates for planned vaginal and elective cesarean deliveries

| ADVERSE OUTCOMES | |

|---|---|

| PLANNED VAGINAL DELIVERY | ELECTIVE CESAREAN |

| FETAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:3,400. All low-risk attempted vaginal deliveries, including those resulting in intrapartum cesarean delivery | Mortality None (n=1,048 low-risk parturients)‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Shoulder dystocia | Transient mild respiratory acidosis |

| Intrauterine hypoxia* | Laceration |

| Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull | Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull32 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage 1:1,900 | Intracranial hemorrhage 1:2,050 |

| Facial nerve injury 1:3,030 | Facial nerve injury 1:2,040† |

| Brachial plexus injury 1:1,300† | Brachial plexus injury 1:2,400 |

| Convulsions 1:1,560 | Convulsions 1:1,160† |

| CNS depression 1:3,230 | CNS depression 1:1,500† |

| Feeding difficulty 1:150 | Feeding difficulty 1:90† |

| Mechanical ventilation 1:390 | Mechanical ventilation 1:140† |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:1,240 | Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:270† |

| Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:90 | Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:30† |

| Respiratory distress syndrome 1:640 | Respiratory distress syndrome 1:470† |

| MATERNAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:8,570 | Mortality 1:2,131‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Urinary incontinence | Endometritis |

| Fecal/flatulence (rectal) incontinence | Wound infection |

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage |

| Deep venous thrombosis | Pelvic infection |

| Subjectively decreased vaginal tone | Deep venous thrombosis |

| Dyspareunia | Delayed breastfeeding/holding neonate |

| Latex allergy | |

| Endometriosis | |

| Adenomyosis | |

| Gallbladder disease | |

| Appendicitis | |

| lleus | |

| Operative complications (ureteral, GI injury) | |

| Scar tissue formation | |

| Controversial | |

| After 3 elective cesarean deliveries, minimal to no protection from urinary incontinence | |

| After menopause and visceroptosis from advancing age, many elderly, regardless of parity or mode of delivery, will have some incontinence25 | |

| * Increased cesarean delivery rate has not decreased incidence of cerebral palsy.33 | |

| † Statistical significance. | |

| ‡ Neonatal and infant mortality in Brazil has decreased with increasing frequency of elective cesarean delivery.34 | |

| SOURCE: Mortality data rounded and adapted from Richardson BS, et al,35 Levine EM, et al,36 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 Morbidity data rounded and adapted from Towner D, et al,38 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 | |

Will poorer women have equal access?

Women in lower socioeconomic groups should not receive substandard care; however, the inverse care “law” describes a disturbing reality: The availability of good medical care is inversely related to the need of the population served.17,18 Thus, the concept of justice, or taking into consideration the greater good for society, is relevant to the elective cesarean debate.

Costs and complications

Cost analysis has shown that expenditures are minimally increased by elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks’ gestation, which also involves more efficient and predictable use of staffing resources.19

Parallel placenta accreta rate

The risk of morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancies exceeding 39 weeks’ gestation may be reduced.1 However, the 10-fold increase in placenta accreta over the past 50 years parallels the rise in cesarean deliveries.20

Fundamentals of patient counseling

Lay out benefits and risks

A detailed comparison of the relative benefits and risks of cesarean delivery (elective, intrapartum, and emergent) versus vaginal delivery (spontaneous, operative, and failed operative) is warranted, along with exploration of the patient’s fears and pressures.1-10,16

Unfortunately, trials comparing all these modes of delivery and all possible adverse outcomes are lacking. (A brief summary of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes is given in TABLE.) Operative vaginal delivery and intrapartum cesarean delivery generally do increase the risk of injury to maternal pelvic structures, as well as the risk of shoulder dystocia and fetal intracranial hemorrhage.

It is important to remain as unbiased as possible when counseling a patient, and to try to balance the conflict between your own autonomy and hers. Acting as a fiduciary for the patient should not involve suppressing your own sound medical judgment. Nor does it remove the patient’s responsibility to remain involved in her care.1-8

Although the patient’s right to refuse treatment is usually considered absolute, she can be prevented from demanding intervention when such intervention is not medically supported.2,4-6,21

Don’t forget future risks

Patients desiring elective cesarean delivery should be apprised of the complications that can arise in subsequent pregnancies.

Some women choose elective cesarean delivery to avoid the hazards of a trial of labor, but may not realize additional hazards, such as placenta accreta, can arise in pregnancies after a cesarean.

Although most women choosing to have only 2 children may experience no complications from elective primary and elective repeat cesarean delivery, some run the risk of placenta previa and possible accreta during the second gestation. These women may experience severe bleeding and require preterm repeat cesarean delivery with hysterectomy. Thus, it is vital to take the patient’s reproductive goals into consideration.

Fear of urinary and rectal incontinence is another reason women often give for desiring cesarean rather than vaginal delivery. However, Rortveit and colleagues22 demonstrated that incontinence affects most elderly women regardless of parity. In addition, it is possible that pregnancy itself contributes to pelvic organ prolapse.10,23,24

Be open to a second opinion

After counseling the patient about risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery, raise the issue of a second opinion, and offer the appropriate referrals if one is desired.4-8,25

ObGyns and patients answer emphatically

BREAKING NEWS

OBG Management Senior, Editor Janelle Yates covered the NIH, Conference March 27–29, 2006 in Bethesda, MD., The panel’s draft statement is available online at http://consensus.nih.gov The final statement is expected this month.

Passions ran high at the NIH State of the Science Conference on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request, last month. On one side were the 17 panel members and Chair Mary E. D’Alton, MD, of Columbia University, who were charged with reviewing the data and responding to questions and comments from audience members—many of whom adamantly opposed patient-choice cesarean.

On the other side were audience members themselves: a mix of physicians, researchers, nurses, nurse-midwives, and the media.

At issue was whether patient choice even exists in obstetrics or is merely a byproduct of physicians’ unwitting influence over their patients.

“My doctor said it, so I did it”

Susan Dentzer, health correspondent for The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, posed the question: “When is a request not really a request but a kind of going along with the moment, often with the provider’s strong preference, and electing the best of the options as they are presented to you at a particular point in time?”

Dentzer, a veteran of elective cesarean, had been invited to speak on the patient’s perspective. She later quipped: “Here’s my complicated decision-making process: My doctor said it, so I did it.”

One ObGyn’s perspective

Millie Sullivan Nelson, head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Christie Clinic in Champaign, Illinois, offered the general obstetrician’s point of view, zeroing in on the high-tech way of giving birth in the 21st century. Over the past 15 years, there has been “a subtle infusion of technology into obstetrics, the goal being to improve the quality of birth outcomes,” she said. “Today’s women may have up to 16 different tubes, drugs, or attachments during their labor process. No wonder some women choose cesarean delivery.”

Dr. Nelson offered a straightforward and engaging recitation of her family history to illustrate the dramatic changes in the typical childbirth experience over the past century. She noted that her maternal grandmother, born in 1895, suffered from rickets, yet beat the odds by giving birth to 4 children—all via cesarean section with vertical incisions. Dr. Nelson’s mother, born in 1926, had 12 children by spontaneous vaginal delivery—5 of them breech presentations. All 12 deliveries took place in “an era of minimal intervention,” she observed.

Dr. Nelson herself had 4 vaginal deliveries. “All of my deliveries were induced to facilitate my personal professional life and that of my obstetrician, who was my partner,” she said. In contrast to her mother and grandmother, who labored and delivered in 2 different rooms, Dr. Nelson had continuous fetal monitoring, her family at her bedside, and delivery in the same room where her labors took place. All 4 deliveries were videotaped.

Too posh to push?

“Now what about today’s woman?” Dr. Nelson asked, choosing pop idol Britney Spears as an example. When Spears chose primary cesarean as her preferred method of delivery, the tabloids accused her of being “too posh to push.”

Despite the furor in some quarters, Dr. Nelson believes times have changed. “My personal opinion is that there has been a gradual acceptance of cesarean section as an option for women, both on the part of the patient and the physician.”

Insurers still behind the curve

Another force shaping the debate is the insurance industry, Dr. Nelson noted. “In my community, precertification of all electively scheduled cesarean sections is required.” When a patient recently asked for cesarean delivery—she was 4 foot 11 and estimated fetal weight was 4,000 g—the insurer refused. The outcome: The woman had “first-stage arrest of labor and descent and ultimately went to cesarean section after 18 hours of labor.”

Litigation for unnecessary cesarean?

Dr. Nelson brought up one of the most influential factors in the cesarean-on-demand debate—the threat of lawsuits: “To my knowledge, there is no history of litigation for unnecessary cesarean section,” she said. “My patient is a consumer of services; I am the supplier of that service. It is a win-lose situation. She expects no pain and suffering and an outcome with zero tolerance for error. She demands 6-sigma quality—and when things go wrong she holds me responsible.”

Attention creates demand

Some attendees were frustrated by the increasing focus on cesarean delivery in general, claiming it raises the profile of cesarean section even further. Better to turn attention to ways of improving vaginal delivery, said Wendy Ponte of Mothering magazine. “When does the NIH plan to hold a similar state-of-the-science conference on optimal vaginal birth practices?”

THE PANEL’S FINDINGS

- Not enough data. There is insufficient evidence “to fully evaluate the benefits and risks of cesarean delivery by maternal request as compared to planned vaginal delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton. Therefore, “any decision to perform a cesarean delivery on maternal request should be carefully individualized and consistent with ethical principles.”

- Not for women wanting large families. “Given that the risks of placenta previa and accreta rise with each cesarean delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton, “cesarean delivery by maternal request is not recommended for women desiring several children.”

- Not before 39 weeks. The increased incidence of respiratory morbidity in term and near-term infants delivered via C-section, “has been well documented in the literature and accounts for a significant number of admissions to intensive care units worldwide,” according to presenter Lucky Jain, MD, MBA, from the Emory University Department of Pediatrics. The panel’s conclusion: “Cesarean delivery by maternal request should not be performed prior to 39 weeks or without verification of lung maturity because of the significant danger of neonatal respiratory complications.”

- Pain of childbirth should not be an issue. Women should be offered adequate analgesia during vaginal delivery so that avoidance of pain is not a reason for requesting cesarean delivery.

- Let the patient raise the subject. The patient should be the one to raise the issue of cesarean delivery by maternal request. “We do not believe it should be brought up by the provider to the patient,” said Dr. D’Alton, adding that, when the patient raises the subject, “a discussion should take place.”

- Forget the notion of a target rate. As panel member Michael Brunskill Bracken, PhD, MPH, of Yale University, explained: “The position that the panel has taken is that rather than create an artificial number, we should concentrate on having modes of delivery that are optimal for the mother and child. And if we can achieve that, then the total C-section rate will be whatever it is, but it will reflect optimal C-sections within a particular population.”

The cesarean delivery rate in the US reached an acme in 2004 at 29.1% of all deliveries. Both the total cesarean rate and the primary cesarean rate have increased each year since 1996. Primary cesarean delivery accounted for 20.6% of all deliveries in 2004—a 40% rise over a decade.12,26

More cesareans, fewer VBACs

Vaginal birth after cesarean has declined from 28.3% to 9.2% since 1996.26 In 2004, 91% of women with 1 cesarean delivery were likely to have repeat cesarean in subsequent deliveries.27

Trend is up in other countries, too

Most developed countries are also seeing increasing cesarean delivery rates. For example, in the United Kingdom, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23% in 2003–2004, up from 17% in 1996–1997.28 In New South Wales, Australia, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23.5% in 2001, up from 17.6% in 1996.29 Data from other countries are older, but typically show increases.

Older “no-risk” gravidas—44% more c-sections For age 35 and older, primiparous women with “no indicated risk” had the greatest frequency of cesarean, according to 1991–2001 US birth certificate data30: 44.2% in 2001—a 44% rise in 10 years.

US trend in cesarean rates per 100 live births

Data for 2003–2004 are preliminary. Due to changes in data collection from implementation of the 2003 revision of the US Standard Certificate of Live Birth, there may be small discontinuities in primary cesarean delivery and VBAC rates in 2003–2004.

SOURCE: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality27

For all ages, primiparous women with no indicated risk had a cesarean delivery rate of 5.5%—a 68% increase in 10 years.

A study from Scotland did report the cesarean delivery rate specifically for “maternal request”: 7.7% in the late 1990s.31

CASE Is her request reasonable?

A 40-year-old primigravid woman presents for her first prenatal visit and asks for cesarean delivery. She explains that she has “waited all her life” for this baby and does not want to risk any harm to the infant during childbirth. She also admits that she is uncomfortable with the unpredictability of childbirth.

CASE Don’t try to dissuade her

The best way to handle this 40-year-old woman’s concerns is to avoid trying to change her mind. Instead, try to understand her view, which no doubt influences her experience of pregnancy, and do your best to remain unbiased as you gather information about her beliefs and constructs. Don’t fall into the trap of merely dispensing facts without her input, or the discussion will be unproductive.

When she reveals that other women have told her about their experiences with long labors and emergency cesarean delivery, you have an opening for discussion. Return to her concerns periodically during the course of antenatal care, telling her what to expect during pregnancy and delivery, and lay out the pros and cons of cesarean vs vaginal delivery. Other helpful resources are a second opinion, birthing classes, and prenatal yoga and expectant mothers’ groups. The next choice is up to you. Once she understands the fetal and maternal risks of cesarean delivery and still prefers an elective cesarean, the next choice is up to you. If you are morally opposed to the idea, refer the patient to another physician who would be willing to perform the cesarean delivery.

The patient should also consider how she will want to proceed if she presents in active labor before her scheduled cesarean section.

The request may be reasonable, but it is impossible to know without an extended discussion and an individualized decision.1-11

Requests for cesarean delivery are becoming more common as the cesarean delivery rate hits all-time highs and the media focuses greater attention on the risks inherent in labor and vaginal delivery. One indicator of the increasing incidence of maternal requests for elective cesarean is the recent State of the Science Conference on the subject, convened by the National Institutes of Health, March 27–29, 2006. (See for more on this conference.)

This article describes what considerations should go into the discussion of cesarean delivery on maternal request, including ways of predicting whether vaginal delivery will be successful, the importance of knowing the number of children desired, the need to observe key ethical principles, and the balancing act necessary between physician and patient autonomy.

Gauging the likelihood of safe vaginal delivery

Cesarean on demand, without a clinical indication, may be reasonable in some circumstances, although we lack data to prove that cesarean delivery is globally superior to vaginal delivery in terms of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Scoring systems may help. For example, maternal obesity is a leading risk factor for cesarean delivery, as are short height, advanced maternal age, large pregnancy weight gain, large birth weight, and increasing gestational age.12

Using scoring systems that assign values to these risk factors, one can reasonably predict a patient’s likelihood of undergoing cesarean delivery after attempted vaginal delivery.13,14

Fetal distress remains wild card

Unfortunately, these scoring tools cannot account for the unpredictability of “fetal distress,” which remains, along with shoulder dystocia, one of the main reasons for performing cesarean delivery in labor.15,16

Ethical concerns

The principles that guide medical decision-making and counseling are:

- Respect for autonomy. The patient has a right to refuse or choose recommended treatments.

- Beneficence. The physician is obligated to promote maternal and fetal well-being, and the patient is obligated to promote the well-being of her fetus.

- Nonmaleficence centers on the goal of avoiding harm and complements the principle of beneficence.

- Justice refers to fairness to the individual and physician and the impact on society.4-7

Consider both short- and long-term consequences

Epidemiologically, physicians bear responsibility for the short- and long-term impacts of their actions. For example, injudicious prescribing of antibiotics has led to drug resistance, and many patients now believe they have the right to request antibiotics for likely viral illness. In obstetrics, the lack of emphasis or counseling on breastfeeding created a cascade effect, which started with affluent women who rejected breastfeeding and eventually reached all socioeconomic groups.

TABLE

Maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality rates for planned vaginal and elective cesarean deliveries

| ADVERSE OUTCOMES | |

|---|---|

| PLANNED VAGINAL DELIVERY | ELECTIVE CESAREAN |

| FETAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:3,400. All low-risk attempted vaginal deliveries, including those resulting in intrapartum cesarean delivery | Mortality None (n=1,048 low-risk parturients)‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Shoulder dystocia | Transient mild respiratory acidosis |

| Intrauterine hypoxia* | Laceration |

| Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull | Fracture of clavicle, humerus, or skull32 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage 1:1,900 | Intracranial hemorrhage 1:2,050 |

| Facial nerve injury 1:3,030 | Facial nerve injury 1:2,040† |

| Brachial plexus injury 1:1,300† | Brachial plexus injury 1:2,400 |

| Convulsions 1:1,560 | Convulsions 1:1,160† |

| CNS depression 1:3,230 | CNS depression 1:1,500† |

| Feeding difficulty 1:150 | Feeding difficulty 1:90† |

| Mechanical ventilation 1:390 | Mechanical ventilation 1:140† |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:1,240 | Persistent pulmonary hypertension 1:270† |

| Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:90 | Transient tachypnea of newborn 1:30† |

| Respiratory distress syndrome 1:640 | Respiratory distress syndrome 1:470† |

| MATERNAL OUTCOMES | |

| Mortality 1:8,570 | Mortality 1:2,131‡ |

| Morbidity | Morbidity |

| Urinary incontinence | Endometritis |

| Fecal/flatulence (rectal) incontinence | Wound infection |

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage |

| Deep venous thrombosis | Pelvic infection |

| Subjectively decreased vaginal tone | Deep venous thrombosis |

| Dyspareunia | Delayed breastfeeding/holding neonate |

| Latex allergy | |

| Endometriosis | |

| Adenomyosis | |

| Gallbladder disease | |

| Appendicitis | |

| lleus | |

| Operative complications (ureteral, GI injury) | |

| Scar tissue formation | |

| Controversial | |

| After 3 elective cesarean deliveries, minimal to no protection from urinary incontinence | |

| After menopause and visceroptosis from advancing age, many elderly, regardless of parity or mode of delivery, will have some incontinence25 | |

| * Increased cesarean delivery rate has not decreased incidence of cerebral palsy.33 | |

| † Statistical significance. | |

| ‡ Neonatal and infant mortality in Brazil has decreased with increasing frequency of elective cesarean delivery.34 | |

| SOURCE: Mortality data rounded and adapted from Richardson BS, et al,35 Levine EM, et al,36 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 Morbidity data rounded and adapted from Towner D, et al,38 or Lilford RJ, et al.37 | |

Will poorer women have equal access?

Women in lower socioeconomic groups should not receive substandard care; however, the inverse care “law” describes a disturbing reality: The availability of good medical care is inversely related to the need of the population served.17,18 Thus, the concept of justice, or taking into consideration the greater good for society, is relevant to the elective cesarean debate.

Costs and complications

Cost analysis has shown that expenditures are minimally increased by elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks’ gestation, which also involves more efficient and predictable use of staffing resources.19

Parallel placenta accreta rate

The risk of morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancies exceeding 39 weeks’ gestation may be reduced.1 However, the 10-fold increase in placenta accreta over the past 50 years parallels the rise in cesarean deliveries.20

Fundamentals of patient counseling

Lay out benefits and risks

A detailed comparison of the relative benefits and risks of cesarean delivery (elective, intrapartum, and emergent) versus vaginal delivery (spontaneous, operative, and failed operative) is warranted, along with exploration of the patient’s fears and pressures.1-10,16

Unfortunately, trials comparing all these modes of delivery and all possible adverse outcomes are lacking. (A brief summary of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes is given in TABLE.) Operative vaginal delivery and intrapartum cesarean delivery generally do increase the risk of injury to maternal pelvic structures, as well as the risk of shoulder dystocia and fetal intracranial hemorrhage.

It is important to remain as unbiased as possible when counseling a patient, and to try to balance the conflict between your own autonomy and hers. Acting as a fiduciary for the patient should not involve suppressing your own sound medical judgment. Nor does it remove the patient’s responsibility to remain involved in her care.1-8

Although the patient’s right to refuse treatment is usually considered absolute, she can be prevented from demanding intervention when such intervention is not medically supported.2,4-6,21

Don’t forget future risks

Patients desiring elective cesarean delivery should be apprised of the complications that can arise in subsequent pregnancies.

Some women choose elective cesarean delivery to avoid the hazards of a trial of labor, but may not realize additional hazards, such as placenta accreta, can arise in pregnancies after a cesarean.

Although most women choosing to have only 2 children may experience no complications from elective primary and elective repeat cesarean delivery, some run the risk of placenta previa and possible accreta during the second gestation. These women may experience severe bleeding and require preterm repeat cesarean delivery with hysterectomy. Thus, it is vital to take the patient’s reproductive goals into consideration.

Fear of urinary and rectal incontinence is another reason women often give for desiring cesarean rather than vaginal delivery. However, Rortveit and colleagues22 demonstrated that incontinence affects most elderly women regardless of parity. In addition, it is possible that pregnancy itself contributes to pelvic organ prolapse.10,23,24

Be open to a second opinion

After counseling the patient about risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery, raise the issue of a second opinion, and offer the appropriate referrals if one is desired.4-8,25

ObGyns and patients answer emphatically

BREAKING NEWS

OBG Management Senior, Editor Janelle Yates covered the NIH, Conference March 27–29, 2006 in Bethesda, MD., The panel’s draft statement is available online at http://consensus.nih.gov The final statement is expected this month.

Passions ran high at the NIH State of the Science Conference on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request, last month. On one side were the 17 panel members and Chair Mary E. D’Alton, MD, of Columbia University, who were charged with reviewing the data and responding to questions and comments from audience members—many of whom adamantly opposed patient-choice cesarean.

On the other side were audience members themselves: a mix of physicians, researchers, nurses, nurse-midwives, and the media.

At issue was whether patient choice even exists in obstetrics or is merely a byproduct of physicians’ unwitting influence over their patients.

“My doctor said it, so I did it”

Susan Dentzer, health correspondent for The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, posed the question: “When is a request not really a request but a kind of going along with the moment, often with the provider’s strong preference, and electing the best of the options as they are presented to you at a particular point in time?”

Dentzer, a veteran of elective cesarean, had been invited to speak on the patient’s perspective. She later quipped: “Here’s my complicated decision-making process: My doctor said it, so I did it.”

One ObGyn’s perspective

Millie Sullivan Nelson, head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Christie Clinic in Champaign, Illinois, offered the general obstetrician’s point of view, zeroing in on the high-tech way of giving birth in the 21st century. Over the past 15 years, there has been “a subtle infusion of technology into obstetrics, the goal being to improve the quality of birth outcomes,” she said. “Today’s women may have up to 16 different tubes, drugs, or attachments during their labor process. No wonder some women choose cesarean delivery.”

Dr. Nelson offered a straightforward and engaging recitation of her family history to illustrate the dramatic changes in the typical childbirth experience over the past century. She noted that her maternal grandmother, born in 1895, suffered from rickets, yet beat the odds by giving birth to 4 children—all via cesarean section with vertical incisions. Dr. Nelson’s mother, born in 1926, had 12 children by spontaneous vaginal delivery—5 of them breech presentations. All 12 deliveries took place in “an era of minimal intervention,” she observed.

Dr. Nelson herself had 4 vaginal deliveries. “All of my deliveries were induced to facilitate my personal professional life and that of my obstetrician, who was my partner,” she said. In contrast to her mother and grandmother, who labored and delivered in 2 different rooms, Dr. Nelson had continuous fetal monitoring, her family at her bedside, and delivery in the same room where her labors took place. All 4 deliveries were videotaped.

Too posh to push?

“Now what about today’s woman?” Dr. Nelson asked, choosing pop idol Britney Spears as an example. When Spears chose primary cesarean as her preferred method of delivery, the tabloids accused her of being “too posh to push.”

Despite the furor in some quarters, Dr. Nelson believes times have changed. “My personal opinion is that there has been a gradual acceptance of cesarean section as an option for women, both on the part of the patient and the physician.”

Insurers still behind the curve

Another force shaping the debate is the insurance industry, Dr. Nelson noted. “In my community, precertification of all electively scheduled cesarean sections is required.” When a patient recently asked for cesarean delivery—she was 4 foot 11 and estimated fetal weight was 4,000 g—the insurer refused. The outcome: The woman had “first-stage arrest of labor and descent and ultimately went to cesarean section after 18 hours of labor.”

Litigation for unnecessary cesarean?

Dr. Nelson brought up one of the most influential factors in the cesarean-on-demand debate—the threat of lawsuits: “To my knowledge, there is no history of litigation for unnecessary cesarean section,” she said. “My patient is a consumer of services; I am the supplier of that service. It is a win-lose situation. She expects no pain and suffering and an outcome with zero tolerance for error. She demands 6-sigma quality—and when things go wrong she holds me responsible.”

Attention creates demand

Some attendees were frustrated by the increasing focus on cesarean delivery in general, claiming it raises the profile of cesarean section even further. Better to turn attention to ways of improving vaginal delivery, said Wendy Ponte of Mothering magazine. “When does the NIH plan to hold a similar state-of-the-science conference on optimal vaginal birth practices?”

THE PANEL’S FINDINGS

- Not enough data. There is insufficient evidence “to fully evaluate the benefits and risks of cesarean delivery by maternal request as compared to planned vaginal delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton. Therefore, “any decision to perform a cesarean delivery on maternal request should be carefully individualized and consistent with ethical principles.”

- Not for women wanting large families. “Given that the risks of placenta previa and accreta rise with each cesarean delivery,” said Dr. D’Alton, “cesarean delivery by maternal request is not recommended for women desiring several children.”

- Not before 39 weeks. The increased incidence of respiratory morbidity in term and near-term infants delivered via C-section, “has been well documented in the literature and accounts for a significant number of admissions to intensive care units worldwide,” according to presenter Lucky Jain, MD, MBA, from the Emory University Department of Pediatrics. The panel’s conclusion: “Cesarean delivery by maternal request should not be performed prior to 39 weeks or without verification of lung maturity because of the significant danger of neonatal respiratory complications.”

- Pain of childbirth should not be an issue. Women should be offered adequate analgesia during vaginal delivery so that avoidance of pain is not a reason for requesting cesarean delivery.

- Let the patient raise the subject. The patient should be the one to raise the issue of cesarean delivery by maternal request. “We do not believe it should be brought up by the provider to the patient,” said Dr. D’Alton, adding that, when the patient raises the subject, “a discussion should take place.”

- Forget the notion of a target rate. As panel member Michael Brunskill Bracken, PhD, MPH, of Yale University, explained: “The position that the panel has taken is that rather than create an artificial number, we should concentrate on having modes of delivery that are optimal for the mother and child. And if we can achieve that, then the total C-section rate will be whatever it is, but it will reflect optimal C-sections within a particular population.”

The cesarean delivery rate in the US reached an acme in 2004 at 29.1% of all deliveries. Both the total cesarean rate and the primary cesarean rate have increased each year since 1996. Primary cesarean delivery accounted for 20.6% of all deliveries in 2004—a 40% rise over a decade.12,26

More cesareans, fewer VBACs

Vaginal birth after cesarean has declined from 28.3% to 9.2% since 1996.26 In 2004, 91% of women with 1 cesarean delivery were likely to have repeat cesarean in subsequent deliveries.27

Trend is up in other countries, too

Most developed countries are also seeing increasing cesarean delivery rates. For example, in the United Kingdom, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23% in 2003–2004, up from 17% in 1996–1997.28 In New South Wales, Australia, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 23.5% in 2001, up from 17.6% in 1996.29 Data from other countries are older, but typically show increases.

Older “no-risk” gravidas—44% more c-sections For age 35 and older, primiparous women with “no indicated risk” had the greatest frequency of cesarean, according to 1991–2001 US birth certificate data30: 44.2% in 2001—a 44% rise in 10 years.

US trend in cesarean rates per 100 live births

Data for 2003–2004 are preliminary. Due to changes in data collection from implementation of the 2003 revision of the US Standard Certificate of Live Birth, there may be small discontinuities in primary cesarean delivery and VBAC rates in 2003–2004.

SOURCE: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality27

For all ages, primiparous women with no indicated risk had a cesarean delivery rate of 5.5%—a 68% increase in 10 years.

A study from Scotland did report the cesarean delivery rate specifically for “maternal request”: 7.7% in the late 1990s.31

1. Paterson-Brown S. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Yes, as long as the woman is fully informed. BMJ. 1998;317:462-463.

2. Amu O, Rajendran S, Bolaji II. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Maternal choice alone should not determine method of delivery. BMJ. 1998;317:463-465.

3. Norwitz ER. Patient choice cesarean delivery. Available at: http://www.UpToDate.com. Accessed July 7, 2005.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgery and patient choice: the ethics of decision making. Committee Opinion No. 289.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2003.

5. Minkoff H, Chervenak FA. Elective primary cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:946-950.

6. Minkoff H, Powderly KR, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Ethical dimensions of elective primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:387-392.

7. Sharma G, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Minkoff H. Ethical considerations in elective cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:404-408.

8. Bewley S, Cockburn J, II. The unfacts of ’request’ caesarean section. BJOG. 2002;109:597-605.

9. Hohlfeld P. Cesarean section on request: a case for common sense. Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2002;42:19-21.

10. Wagner M. Choosing caesarean section. Lancet. 2000;356:1677-1680.

11. Nygaard I, Cruikshank DP. Should all women be offered elective cesarean delivery? Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:217-219.

12. Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Sutton PD. Preliminary births for 2004. Health E-stats. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. Released October 28, 2005. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelim_bir ths/prelim_births04.htm. Accessed April 4, 2006.

13. Chen G, Uryasev S, Young TK. On prediction of the cesarean delivery risk in a large private practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:616-624.

14. Smith GC, Dellens M, White IR, Pell JP. Combined logistic and Bayesian modeling of cesarean section risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:2029-2034.

15. Liston WA. Rising caesarean section rates: can evolution and ecology explain some of the difficulties of modern childbirth? J R Soc Med. 2003;95:559-561.

16. Anderson GM. Making sense of rising caesarean section rates. BMJ. 2004;329:696-697.

17. Johanson RB, El-Timini S, Rigby C, Young P, Jones P. Caesarean section by choice could fulfill the inverse care law. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:20-22.

18. Belizan JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ. 1999;319:1397-1400.

19. Bost BW. Cesarean delivery on demand: what will it cost? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1418-1423.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Placenta accreta. Committee Opinion No. 266.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2002.

21. Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Inadequacies with the ACOG and AAP statements on managing ethical conflict during the intrapartum period. J Clin Ethics. 1991;2:23-24.

22. Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S. Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:900-907.

23. Dietz HP, Bennett MJ. The effect of childbirth on pelvic organ mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:223-228.

24. Lal M. Prevention of urinary and anal incontinence: role of elective cesarean delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:439-448.

25. Belizan JM, Villar J, Alexander S, et al. Latin American Caesarean Section Study Group. Mandatory second opinion to reduce rates of unnecessary caesarean sections in Latin America: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1934-1940.

26. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2005;54(2):15-17.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_02.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2006.

27. Viswanathan M, Visco AG, Hartmann K, et al. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 133. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2006. AHRQ publication 06–E009.

28. Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. NHS maternity statistics, England 2003–04 [Web page]. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/56/03/04115603.xls. Accessed April 6, 2006.

29. Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health. New South Wales. Mothers and babies 2001. N S W Public Health Bull. 2002;13(S–4). Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/public-health/mdc/mdcrep01.html. Accessed April 10, 2006.

30. Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman MF. Rise in “no indicated risk” primary cesareans in the United States, 1991–2001: cross-sectional analysis. BMJ. 2005;330:71-72.

31. Wilkinson C, Mcllwaine G, Boulton-Jones C, et al. Is a rising caesarean section rate inevitable? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:45-52.

32. Dupuis O, Silveira R, Dupont C, Mottolese C, Kahn P, Dittmar A, Rudigoz R. Comparison of instrument-associated and spontaneous obstetric depressed skull fractures in a cohort of 68 neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:165-170.

33. Wax JR, Cartin A, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Patient choice cesarean: an evidence-based review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:601-616.

34. Groom K, Brown SP. Caesarean section controversy. The rate of caesarean sections is not the issue. BMJ. 2000;320:1072-1073; author reply 1074.

35. Richardson BS, Czikk MJ, daSilva O, Natale R. The impact of labor at term on measures of neonatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:219-226.

36. Levine EM, Ghai V, Barton JJ, Strom CM. Mode of delivery and risk of respiratory diseases in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;439-442.

37. Lilford RJ, van Coeverden de Groot HA, Moore PJ, Bingham P. The relative risks of caesarean section (intrapartum and elective) and vaginal delivery: a detailed analysis to exclude the effects of medical disorders and other acute pre-existing physiological disturbances. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:883-892.

38. Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1709-1714.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Paterson-Brown S. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Yes, as long as the woman is fully informed. BMJ. 1998;317:462-463.

2. Amu O, Rajendran S, Bolaji II. Should doctors perform an elective caesarean section on request? Maternal choice alone should not determine method of delivery. BMJ. 1998;317:463-465.

3. Norwitz ER. Patient choice cesarean delivery. Available at: http://www.UpToDate.com. Accessed July 7, 2005.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgery and patient choice: the ethics of decision making. Committee Opinion No. 289.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2003.

5. Minkoff H, Chervenak FA. Elective primary cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:946-950.

6. Minkoff H, Powderly KR, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Ethical dimensions of elective primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:387-392.

7. Sharma G, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Minkoff H. Ethical considerations in elective cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:404-408.

8. Bewley S, Cockburn J, II. The unfacts of ’request’ caesarean section. BJOG. 2002;109:597-605.

9. Hohlfeld P. Cesarean section on request: a case for common sense. Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2002;42:19-21.

10. Wagner M. Choosing caesarean section. Lancet. 2000;356:1677-1680.

11. Nygaard I, Cruikshank DP. Should all women be offered elective cesarean delivery? Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:217-219.

12. Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Sutton PD. Preliminary births for 2004. Health E-stats. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. Released October 28, 2005. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelim_bir ths/prelim_births04.htm. Accessed April 4, 2006.

13. Chen G, Uryasev S, Young TK. On prediction of the cesarean delivery risk in a large private practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:616-624.

14. Smith GC, Dellens M, White IR, Pell JP. Combined logistic and Bayesian modeling of cesarean section risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:2029-2034.

15. Liston WA. Rising caesarean section rates: can evolution and ecology explain some of the difficulties of modern childbirth? J R Soc Med. 2003;95:559-561.

16. Anderson GM. Making sense of rising caesarean section rates. BMJ. 2004;329:696-697.

17. Johanson RB, El-Timini S, Rigby C, Young P, Jones P. Caesarean section by choice could fulfill the inverse care law. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:20-22.

18. Belizan JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ. 1999;319:1397-1400.

19. Bost BW. Cesarean delivery on demand: what will it cost? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1418-1423.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Placenta accreta. Committee Opinion No. 266.Washington, DC: ACOG; 2002.

21. Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Inadequacies with the ACOG and AAP statements on managing ethical conflict during the intrapartum period. J Clin Ethics. 1991;2:23-24.

22. Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S. Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:900-907.

23. Dietz HP, Bennett MJ. The effect of childbirth on pelvic organ mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:223-228.

24. Lal M. Prevention of urinary and anal incontinence: role of elective cesarean delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:439-448.

25. Belizan JM, Villar J, Alexander S, et al. Latin American Caesarean Section Study Group. Mandatory second opinion to reduce rates of unnecessary caesarean sections in Latin America: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1934-1940.

26. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2005;54(2):15-17.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_02.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2006.

27. Viswanathan M, Visco AG, Hartmann K, et al. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 133. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2006. AHRQ publication 06–E009.

28. Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. NHS maternity statistics, England 2003–04 [Web page]. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/56/03/04115603.xls. Accessed April 6, 2006.

29. Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health. New South Wales. Mothers and babies 2001. N S W Public Health Bull. 2002;13(S–4). Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/public-health/mdc/mdcrep01.html. Accessed April 10, 2006.

30. Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman MF. Rise in “no indicated risk” primary cesareans in the United States, 1991–2001: cross-sectional analysis. BMJ. 2005;330:71-72.

31. Wilkinson C, Mcllwaine G, Boulton-Jones C, et al. Is a rising caesarean section rate inevitable? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:45-52.

32. Dupuis O, Silveira R, Dupont C, Mottolese C, Kahn P, Dittmar A, Rudigoz R. Comparison of instrument-associated and spontaneous obstetric depressed skull fractures in a cohort of 68 neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:165-170.

33. Wax JR, Cartin A, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Patient choice cesarean: an evidence-based review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:601-616.

34. Groom K, Brown SP. Caesarean section controversy. The rate of caesarean sections is not the issue. BMJ. 2000;320:1072-1073; author reply 1074.

35. Richardson BS, Czikk MJ, daSilva O, Natale R. The impact of labor at term on measures of neonatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:219-226.

36. Levine EM, Ghai V, Barton JJ, Strom CM. Mode of delivery and risk of respiratory diseases in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;439-442.

37. Lilford RJ, van Coeverden de Groot HA, Moore PJ, Bingham P. The relative risks of caesarean section (intrapartum and elective) and vaginal delivery: a detailed analysis to exclude the effects of medical disorders and other acute pre-existing physiological disturbances. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:883-892.

38. Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1709-1714.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.