User login

Physicians are placed in positions of leadership by the medical team, by the community, and by society, particularly during times of crisis such as the COVID pandemic. They are looked to by the media at times of health care news such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade.1 In a 2015 survey of resident physicians, two-thirds agreed that a formalized leadership curriculum would help them become better supervisors and clinicians.2 While all physicians are viewed as leaders, the concept of leadership is rarely, if ever, described or developed as a part of medical training. This month’s column will provide insights into defining leadership as a physician in the medical and administrative settings.

Benefits of effective leadership

Physicians, whether they are clinicians, researchers, administrators, or teachers, are expected to oversee and engage their teams. A report by the Institute of Medicine recommended that academic health centers “develop leaders at all levels who can manage the organizational and system changes necessary to improve health through innovation in health professions education, patient care, and research.”3 Hospitals with higher-rated management practices and more highly rated boards of directors have been shown to deliver higher-quality care and better clinical outcomes, including lower mortality.

To illustrate, the clinicians at the Mayo Clinic annually rate their supervisors on a Leader Index, a simple 12-question survey of five leadership domains: truthfulness, transparency, character, capability, and partnership. All supervisors were physicians and scientists. Their findings revealed that for each one-point increase in composite leadership score, there was a 3.3% decrease in the likelihood of burnout and a 9.0% increase in the likelihood of satisfaction in the physicians supervised.4

Interprofessional teamwork and engagement are vital skills for a leader to create a successful team. Enhanced management practices have also been associated with higher patient approval ratings and better financial performance. Effective leadership additionally affects physician well-being, with stronger leadership associated with less physician burnout and higher satisfaction.5

Leadership styles enhance quality measures in health care.6 The most effective leadership styles are ones in which the staff feels they are part of a team, are engaged, and are mentored.7 While leadership styles can vary, the common theme is staff engagement. An authoritative style leader is one who mobilizes the team toward a vision, that is, “Come with me.” An affiliative style leader creates harmony and builds emotional bonds where “people come first.” Democratic leaders forge a consensus through staff participation by asking, “What do you think?” Finally, a leader who uses a coaching style helps staff to identify their strengths and weaknesses and work toward improvement. These leadership behaviors are in contradistinction to the unsuccessful coercive leader who demands immediate compliance, that is, “Do what I tell you.”

Five fundamental leadership principles are shown in Table 1.8

Effective leaders have an open (growth) mindset, unwavering attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and to building relationships and trust; they practice effective communication and listening, focus on results, and cocreate support structures.

A growth mindset is the belief that one’s abilities are not innate but can improve through effort and learning.9

Emotional intelligence

A survey of business senior managers rated the qualities found in the most outstanding leaders. Using objective criteria like profitability the study psychologists interviewed the highest-rated leaders to compare their capabilities. While intellects and cognitive skills were important, the results showed that emotional intelligence (EI) was twice as important as technical skills and IQ.10 As an example, in a 1996 study, when senior managers had an optimal level of EI, their division’s yearly earnings were 20% higher than estimated.11

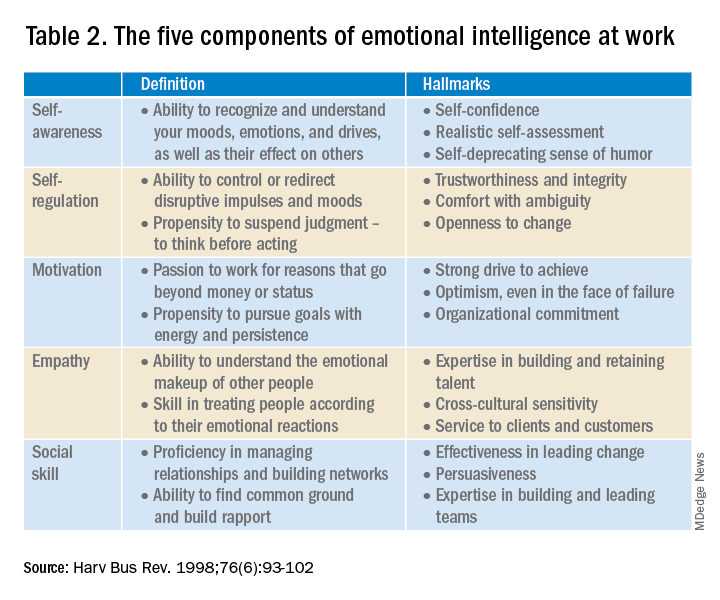

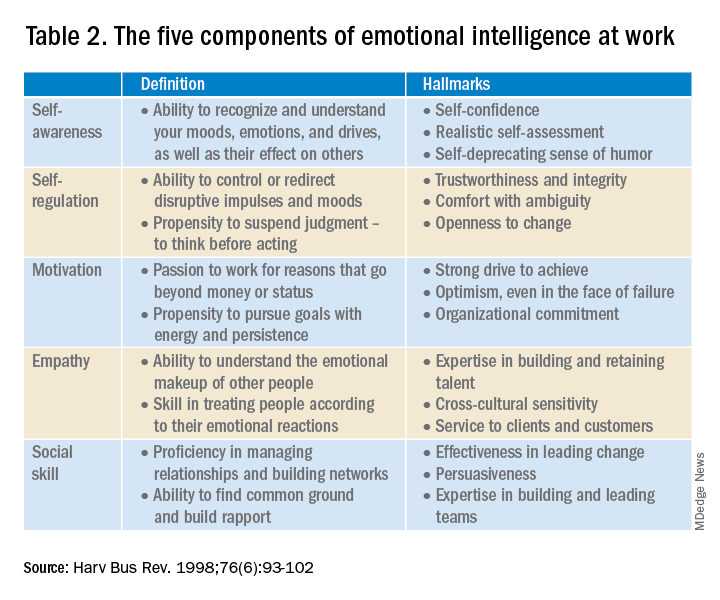

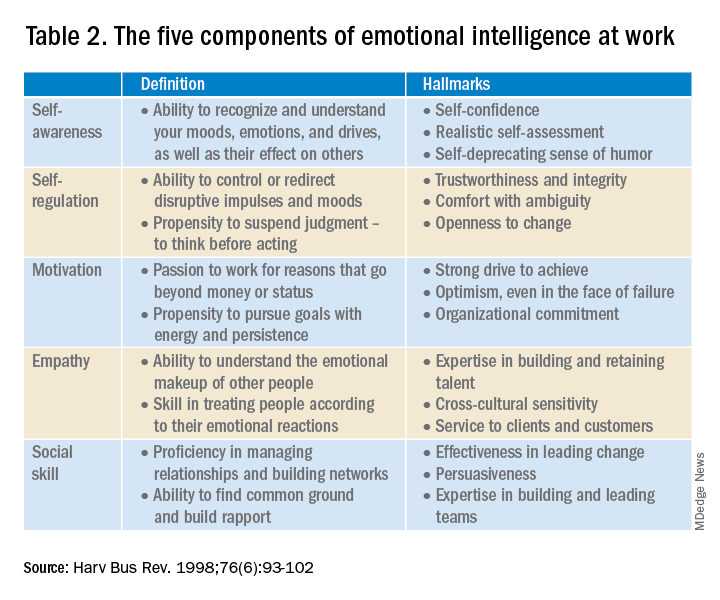

EI is a leadership competency that deals with the ability to understand and manage your own emotions and your interactions with others.10 At the Cleveland Clinic, EI is exemplified by the acronym HEART, whereby the team strives to improve the patient experience, mainly when an error occurs. The health care team is using EI by showing its the ability to Hear, Empathize, Apologize, Reply, and Thank. When an untoward event occurs, the physician, as the leader of the team, must lead by example when communicating with staff and patients. EI consists of five components (Table 2).13

- Self-awareness is insight by which you can improve. Maintaining a journal of your daily thoughts may assist with this as well as simply pausing to pay attention during times of heightened emotions.

- Self-regulation shows control, that is, behaving according to your values, and being accountable and calm when challenged.

- Purpose, knowing your “why,” produces motivation and helps maintain optimism.

- Empathy shows the ability to understand the emotions of other people.

- Social skill is the ability to establish mutually rewarding relationships.

Given all the above benefits, it is no surprise that companies are actively trying use artificial intelligence to improve EI.12

Learning to be a leader

In medical school, students are expected to develop skills to handle and resolve conflicts, learn to share leadership, take mutual responsibility, and monitor their own performance.13 Although training of young physicians in leadership is not unprecedented, a systemic review revealed a lack of analytic studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching methods.14 During undergraduate medical education, standard curricula and methods of instruction on leadership are not established, resulting in variable outcomes.

The Association of American Medical Colleges offers a curriculum, “Preparing Medical Students to Be Physician Leaders: A Leadership Training Program for Students Designed and Led by Students.”15 The objectives of this training are to help students identify their “personal style of leadership, recognize strengths and weaknesses, utilize effective communication strategies, appropriately delegate team member responsibilities, and provide constructive feedback to help improve team function.”

Take-home points

Following the completion of formal medical education, physicians are thrust into leadership roles. The key to being an effective leader is using EI to mentor the team and make staff feel connected to the team’s meaning and purpose, so they feel valued.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Carsen S and Xia C. McGill J Med. 2006 Jan;9(1):1-2.

2. Jardine D et al. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307-9.

3. Institute of Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. July 2004;11(7):802-6.

4. Shanafelt TD et al. Mayo Clin Proc. April 2015;90(4):432-40.

5. Rotenstein LS et al. Harv Bus Rev. Oct. 17, 2018.

6. Sfantou SF. Healthcare 2017;5(4):73.

7. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. March-April 2000.

8. Collins-Nakai R. McGill J Med [Internet]. 2020 Dec. 1 [cited 2023 Mar. 28];9(1).

9. Dweck C. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 13, 2016.

10. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. 1998 Nov-Dec;76(6):93-102..

11. Goleman D et al. Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2002.12. Limon D and Plaster B. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 25, 2022.

13. Chen T-Y. Tzu Chi Med J. Apr–Jun 2018;30(2):66-70.

14. Kumar B et al. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:175.

15. Richards K et al. Med Ed Portal. Dec. 13 2019.

Physicians are placed in positions of leadership by the medical team, by the community, and by society, particularly during times of crisis such as the COVID pandemic. They are looked to by the media at times of health care news such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade.1 In a 2015 survey of resident physicians, two-thirds agreed that a formalized leadership curriculum would help them become better supervisors and clinicians.2 While all physicians are viewed as leaders, the concept of leadership is rarely, if ever, described or developed as a part of medical training. This month’s column will provide insights into defining leadership as a physician in the medical and administrative settings.

Benefits of effective leadership

Physicians, whether they are clinicians, researchers, administrators, or teachers, are expected to oversee and engage their teams. A report by the Institute of Medicine recommended that academic health centers “develop leaders at all levels who can manage the organizational and system changes necessary to improve health through innovation in health professions education, patient care, and research.”3 Hospitals with higher-rated management practices and more highly rated boards of directors have been shown to deliver higher-quality care and better clinical outcomes, including lower mortality.

To illustrate, the clinicians at the Mayo Clinic annually rate their supervisors on a Leader Index, a simple 12-question survey of five leadership domains: truthfulness, transparency, character, capability, and partnership. All supervisors were physicians and scientists. Their findings revealed that for each one-point increase in composite leadership score, there was a 3.3% decrease in the likelihood of burnout and a 9.0% increase in the likelihood of satisfaction in the physicians supervised.4

Interprofessional teamwork and engagement are vital skills for a leader to create a successful team. Enhanced management practices have also been associated with higher patient approval ratings and better financial performance. Effective leadership additionally affects physician well-being, with stronger leadership associated with less physician burnout and higher satisfaction.5

Leadership styles enhance quality measures in health care.6 The most effective leadership styles are ones in which the staff feels they are part of a team, are engaged, and are mentored.7 While leadership styles can vary, the common theme is staff engagement. An authoritative style leader is one who mobilizes the team toward a vision, that is, “Come with me.” An affiliative style leader creates harmony and builds emotional bonds where “people come first.” Democratic leaders forge a consensus through staff participation by asking, “What do you think?” Finally, a leader who uses a coaching style helps staff to identify their strengths and weaknesses and work toward improvement. These leadership behaviors are in contradistinction to the unsuccessful coercive leader who demands immediate compliance, that is, “Do what I tell you.”

Five fundamental leadership principles are shown in Table 1.8

Effective leaders have an open (growth) mindset, unwavering attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and to building relationships and trust; they practice effective communication and listening, focus on results, and cocreate support structures.

A growth mindset is the belief that one’s abilities are not innate but can improve through effort and learning.9

Emotional intelligence

A survey of business senior managers rated the qualities found in the most outstanding leaders. Using objective criteria like profitability the study psychologists interviewed the highest-rated leaders to compare their capabilities. While intellects and cognitive skills were important, the results showed that emotional intelligence (EI) was twice as important as technical skills and IQ.10 As an example, in a 1996 study, when senior managers had an optimal level of EI, their division’s yearly earnings were 20% higher than estimated.11

EI is a leadership competency that deals with the ability to understand and manage your own emotions and your interactions with others.10 At the Cleveland Clinic, EI is exemplified by the acronym HEART, whereby the team strives to improve the patient experience, mainly when an error occurs. The health care team is using EI by showing its the ability to Hear, Empathize, Apologize, Reply, and Thank. When an untoward event occurs, the physician, as the leader of the team, must lead by example when communicating with staff and patients. EI consists of five components (Table 2).13

- Self-awareness is insight by which you can improve. Maintaining a journal of your daily thoughts may assist with this as well as simply pausing to pay attention during times of heightened emotions.

- Self-regulation shows control, that is, behaving according to your values, and being accountable and calm when challenged.

- Purpose, knowing your “why,” produces motivation and helps maintain optimism.

- Empathy shows the ability to understand the emotions of other people.

- Social skill is the ability to establish mutually rewarding relationships.

Given all the above benefits, it is no surprise that companies are actively trying use artificial intelligence to improve EI.12

Learning to be a leader

In medical school, students are expected to develop skills to handle and resolve conflicts, learn to share leadership, take mutual responsibility, and monitor their own performance.13 Although training of young physicians in leadership is not unprecedented, a systemic review revealed a lack of analytic studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching methods.14 During undergraduate medical education, standard curricula and methods of instruction on leadership are not established, resulting in variable outcomes.

The Association of American Medical Colleges offers a curriculum, “Preparing Medical Students to Be Physician Leaders: A Leadership Training Program for Students Designed and Led by Students.”15 The objectives of this training are to help students identify their “personal style of leadership, recognize strengths and weaknesses, utilize effective communication strategies, appropriately delegate team member responsibilities, and provide constructive feedback to help improve team function.”

Take-home points

Following the completion of formal medical education, physicians are thrust into leadership roles. The key to being an effective leader is using EI to mentor the team and make staff feel connected to the team’s meaning and purpose, so they feel valued.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Carsen S and Xia C. McGill J Med. 2006 Jan;9(1):1-2.

2. Jardine D et al. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307-9.

3. Institute of Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. July 2004;11(7):802-6.

4. Shanafelt TD et al. Mayo Clin Proc. April 2015;90(4):432-40.

5. Rotenstein LS et al. Harv Bus Rev. Oct. 17, 2018.

6. Sfantou SF. Healthcare 2017;5(4):73.

7. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. March-April 2000.

8. Collins-Nakai R. McGill J Med [Internet]. 2020 Dec. 1 [cited 2023 Mar. 28];9(1).

9. Dweck C. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 13, 2016.

10. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. 1998 Nov-Dec;76(6):93-102..

11. Goleman D et al. Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2002.12. Limon D and Plaster B. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 25, 2022.

13. Chen T-Y. Tzu Chi Med J. Apr–Jun 2018;30(2):66-70.

14. Kumar B et al. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:175.

15. Richards K et al. Med Ed Portal. Dec. 13 2019.

Physicians are placed in positions of leadership by the medical team, by the community, and by society, particularly during times of crisis such as the COVID pandemic. They are looked to by the media at times of health care news such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade.1 In a 2015 survey of resident physicians, two-thirds agreed that a formalized leadership curriculum would help them become better supervisors and clinicians.2 While all physicians are viewed as leaders, the concept of leadership is rarely, if ever, described or developed as a part of medical training. This month’s column will provide insights into defining leadership as a physician in the medical and administrative settings.

Benefits of effective leadership

Physicians, whether they are clinicians, researchers, administrators, or teachers, are expected to oversee and engage their teams. A report by the Institute of Medicine recommended that academic health centers “develop leaders at all levels who can manage the organizational and system changes necessary to improve health through innovation in health professions education, patient care, and research.”3 Hospitals with higher-rated management practices and more highly rated boards of directors have been shown to deliver higher-quality care and better clinical outcomes, including lower mortality.

To illustrate, the clinicians at the Mayo Clinic annually rate their supervisors on a Leader Index, a simple 12-question survey of five leadership domains: truthfulness, transparency, character, capability, and partnership. All supervisors were physicians and scientists. Their findings revealed that for each one-point increase in composite leadership score, there was a 3.3% decrease in the likelihood of burnout and a 9.0% increase in the likelihood of satisfaction in the physicians supervised.4

Interprofessional teamwork and engagement are vital skills for a leader to create a successful team. Enhanced management practices have also been associated with higher patient approval ratings and better financial performance. Effective leadership additionally affects physician well-being, with stronger leadership associated with less physician burnout and higher satisfaction.5

Leadership styles enhance quality measures in health care.6 The most effective leadership styles are ones in which the staff feels they are part of a team, are engaged, and are mentored.7 While leadership styles can vary, the common theme is staff engagement. An authoritative style leader is one who mobilizes the team toward a vision, that is, “Come with me.” An affiliative style leader creates harmony and builds emotional bonds where “people come first.” Democratic leaders forge a consensus through staff participation by asking, “What do you think?” Finally, a leader who uses a coaching style helps staff to identify their strengths and weaknesses and work toward improvement. These leadership behaviors are in contradistinction to the unsuccessful coercive leader who demands immediate compliance, that is, “Do what I tell you.”

Five fundamental leadership principles are shown in Table 1.8

Effective leaders have an open (growth) mindset, unwavering attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and to building relationships and trust; they practice effective communication and listening, focus on results, and cocreate support structures.

A growth mindset is the belief that one’s abilities are not innate but can improve through effort and learning.9

Emotional intelligence

A survey of business senior managers rated the qualities found in the most outstanding leaders. Using objective criteria like profitability the study psychologists interviewed the highest-rated leaders to compare their capabilities. While intellects and cognitive skills were important, the results showed that emotional intelligence (EI) was twice as important as technical skills and IQ.10 As an example, in a 1996 study, when senior managers had an optimal level of EI, their division’s yearly earnings were 20% higher than estimated.11

EI is a leadership competency that deals with the ability to understand and manage your own emotions and your interactions with others.10 At the Cleveland Clinic, EI is exemplified by the acronym HEART, whereby the team strives to improve the patient experience, mainly when an error occurs. The health care team is using EI by showing its the ability to Hear, Empathize, Apologize, Reply, and Thank. When an untoward event occurs, the physician, as the leader of the team, must lead by example when communicating with staff and patients. EI consists of five components (Table 2).13

- Self-awareness is insight by which you can improve. Maintaining a journal of your daily thoughts may assist with this as well as simply pausing to pay attention during times of heightened emotions.

- Self-regulation shows control, that is, behaving according to your values, and being accountable and calm when challenged.

- Purpose, knowing your “why,” produces motivation and helps maintain optimism.

- Empathy shows the ability to understand the emotions of other people.

- Social skill is the ability to establish mutually rewarding relationships.

Given all the above benefits, it is no surprise that companies are actively trying use artificial intelligence to improve EI.12

Learning to be a leader

In medical school, students are expected to develop skills to handle and resolve conflicts, learn to share leadership, take mutual responsibility, and monitor their own performance.13 Although training of young physicians in leadership is not unprecedented, a systemic review revealed a lack of analytic studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching methods.14 During undergraduate medical education, standard curricula and methods of instruction on leadership are not established, resulting in variable outcomes.

The Association of American Medical Colleges offers a curriculum, “Preparing Medical Students to Be Physician Leaders: A Leadership Training Program for Students Designed and Led by Students.”15 The objectives of this training are to help students identify their “personal style of leadership, recognize strengths and weaknesses, utilize effective communication strategies, appropriately delegate team member responsibilities, and provide constructive feedback to help improve team function.”

Take-home points

Following the completion of formal medical education, physicians are thrust into leadership roles. The key to being an effective leader is using EI to mentor the team and make staff feel connected to the team’s meaning and purpose, so they feel valued.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Carsen S and Xia C. McGill J Med. 2006 Jan;9(1):1-2.

2. Jardine D et al. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307-9.

3. Institute of Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. July 2004;11(7):802-6.

4. Shanafelt TD et al. Mayo Clin Proc. April 2015;90(4):432-40.

5. Rotenstein LS et al. Harv Bus Rev. Oct. 17, 2018.

6. Sfantou SF. Healthcare 2017;5(4):73.

7. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. March-April 2000.

8. Collins-Nakai R. McGill J Med [Internet]. 2020 Dec. 1 [cited 2023 Mar. 28];9(1).

9. Dweck C. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 13, 2016.

10. Goleman D. Harv Bus Rev. 1998 Nov-Dec;76(6):93-102..

11. Goleman D et al. Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2002.12. Limon D and Plaster B. Harv Bus Rev. Jan. 25, 2022.

13. Chen T-Y. Tzu Chi Med J. Apr–Jun 2018;30(2):66-70.

14. Kumar B et al. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:175.

15. Richards K et al. Med Ed Portal. Dec. 13 2019.