User login

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

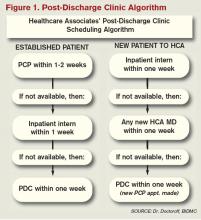

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.