User login

Dr. M is facing financial challenges with his fledgling private practice and begins consulting at a weight loss clinic to supplement his income. He finds him-self attracted to Ms. Y, a weight-loss patient he is treating. They seem to click interpersonally, and he extends his office visits with her. Ms. Y clearly enjoys this extra attention, and Dr. M begins including personal disclosures in his conversations with her.

In his residency training, Dr. M was taught never to date a current or former patient, but he views this situation as different. Ms. Y is seeing him only for weight loss, and he rationalizes that he is providing her with medical care, not “psychiatric” care. On 2 occasions he gives her a limited quantity of benzodiazepines for mild anxiety, which he considers a transitory stress-related condition and not an “official” DSM-IV-TR disorder.

Eventually, Dr. M asks Ms. Y to dinner and she accepts. After they begin dating, he decides to transfer her to another clinic physician “just to be safe.”

Although many psychiatrists assume that psychiatrist/patient boundaries are well defined by ethical and legal standards, boundary issues are a complex and controversial aspect of clinical practice. Psychoanalysts initially defined psychiatrist/patient boundaries as a way of structuring the unique and intimate relationship that evolves during analysis.1,2 The introduction of other therapeutic techniques and changes in health care funding have combined to make psychiatrist/patient boundaries far more complex.

Boundary violations are about exploitation. Both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Canadian Medical Association warn members to “scrupulously avoid using the physician/patient relationship to gratify their own emotional, financial, and sexual needs.”3

Boundaries represent the edge of appropriate behavior and serve 2 important purposes:

- They separate the therapeutic relationship from social, sexual, romantic, and business relationships and from relationships that transform into caretaking of the psychiatrist by the patient.

- They structure the professional relationship in ways that maintain the identity and roles of the patient and the professional.4

Psychiatry’s unique dilemmas

As are all physicians, psychiatrists are governed by the 9 biomedical ethics set forth in the AMA’s Principles of Medical Ethics. The American Psychiatric Association (APA), however, acknowledges that psychiatry has a “broader set of moral and ethical problems and dilemmas” that are unique to and magnified by the mental health setting.5 The APA has adopted 39 standards in addition to those set forth by the AMA. The first standard captures the unique responsibilities inherent in the psychiatrist/ patient relationship: A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient (Box).6

Sexual contact with patients is inherently harmful to patients, always unethical, and usually illegal.7 The rate of sexual misconduct among psychiatrists is unknown. National Practitioner Data Bank information is not available to the general public.8 Based on literature reviews and data from individual states9,10 and government agencies,11 an estimated 6% to10% of psychiatrists have had inappropriate sexual relations with patients.12 Estimates of sexual misconduct by psychiatrists:

All physicians are required to practice in accordance with the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics. Because these guidelines can be difficult to interpret for psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association provides further guidance with The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. The following excerpts from annotations to the first 2 principles spell out the basic concepts underlying appropriate psychiatrist/patient boundaries:

‘A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient. The psychiatrist shall be ever vigilant about the impact that his or her conduct has upon the boundaries of the doctor/patient relationship, and thus upon the well-being of the patient. These requirements become particularly important because of the essentially private, highly personal, and sometimes intensely emotional nature of the relationship established with the psychiatrist.

‘The requirement that the physician conduct himself/herself with propriety in his or her profession and in all the actions of his or her life is especially important in the case of the psychiatrist because the patient tends to model his or her behavior after that of his or her psychiatrist by identification. Further, the necessary intensity of the treatment relationship may tend to activate sexual and other needs and fantasies on the part of both patient and psychiatrist, while weakening the objectivity necessary for control. Additionally, the inherent inequality in the doctor-patient relationship may lead to exploitation of the patient. Sexual activity with a current or former patient is unethical.’

Source: Reference 6

- increase if misconduct is based on patient complaints

- decrease if self-reports are used

- decrease even further if based on official investigations.4

American psychoanalyst Frieda Fromm-Reichman reportedly offered her colleagues a not-so-humorous admonition: “Don’t have sex with your patients; you will only disappoint them.”4

Nonsexual boundary violations—such as accepting gifts, entering into business arrangements, or trying to influence a patient’s political or religious beliefs or sexual orientation—occur more frequently than sexual misconduct.12 Although the impact of nonsexual violations generally is less serious, any relationship that coexists with the therapeutic relationship has the potential to impair your judgment and contaminate your ability to focus exclusively on your patient’s well-being.13 Be cautious about any decision that could affect the treatment relationship.14

Triangle relationships.Originally, this term referred to the patient/therapist/psychiatrist triad. The term now has a broader meaning that includes:

- encroachments into care by managed care companies and government regulatory agencies

- interactions with the patient’s family members

- providing psychiatric care in non-traditional settings such as schools or prisons

- serving as an expert witness.15

The framework of trust once considered a core feature of the psychiatrist/patient relationship is being undermined by a funding system that demands efficiency and economy.16 Recognizing that some settings sacrifice patients’ clinical needs to the interests of the organization, the APA’s Guidelines for Ethical Practice in Organized Settings stipulate that the psychiatrist must “strive to resolve these conflicts in a manner that is likely to be of greatest benefit to the patient” by (for example):

- informing a patient of financial incentives or penalties that limit your ability to provide appropriate treatment

- not with holding information the patient could use to make informed treatment decisions, including treatment options not provided by you.6

Psychiatrists who doubt that the system—such as a mental health clinic, hospital, or managed care contract provider or reviewer—upholds the standard of acceptable care have the “ethical responsibility” to improve the system.6

Another change in mental health care attempts to limit psychiatrists to “medication management” so that less expensive professionals can provide adjunctive therapies. The treating psychiatrist bears some responsibility, however, for the appropriateness of the patient’s therapeutic options.6 According to Reid,17 psychiatrists are responsible for knowing something about the care, treatment style, credentials, and even ethics of those with whom they share treatment or to whom they refer patients.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Code of Ethics addresses the unique challenges encountered when a patient’s opinions differ from those of parents and other authority figures, such as school staff. The AACAP standards consistently direct the psychiatrist to keep the child’s interest primary, explaining that “the child and adolescent psychiatrist may be called upon to participate in attempts to control or change the behavior of children or adolescents…[but] the child and adolescent psychiatrist will avoid acting solely as an agent of the parents, guardians, or agencies.”18

Another triangle can occur when a treating psychiatrist serves as an expert witness or other evaluator for forensic or disability purposes. The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL) recommends that psychiatrists avoid acting as expert witnesses for their patients or performing patient evaluations for legal purposes.19 While recognizing that certain situations may require a psychiatrist to serve a dual role, the AAPL stresses that sensitivity to differences between clinical and legal obligations remains important.

Avoid serving as an expert witness for your patient. The intrusion of another role into the doctor/patient relationship can alter the treatment process and permanently color future inter actions. Likewise, treating an individual whom you previously evaluated for forensic purposes raises similar concerns, including the possibility of a mercenary motivation. Even when no such motivation exists, these situations can create the appearance that you have conscripted a vulnerable individual into your practice.

Emerging trends

Crossings vs violations. Efforts to distinguish when an action is unethical or illegal have led some to differentiate boundary crossings from boundary violations. Unfortunately, the 2 terms continue to be used synonymously, which confuses rather than clarifies the issue:

- Boundary crossings are aimed at enhancing the therapist’s treatment efforts—such as a hug instead of a hand shake at the end of a particularly difficult treatment session.

- Boundary violations are invariably harmful and unethical because they serve the therapist’s needs rather than the patient’s needs or the therapeutic process.20

Rather than trying to differentiate between crossings and violations or to determine under what circumstances changing boundaries is acceptable, Sheets21 conceptualizes a boundary not as a line to cross, but as a continuum of behavior. Under-involvement is at one end, over-involvement at the other, and a “zone of helpfulness” is in the middle.

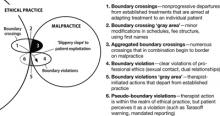

Glass uses a Venn diagram to illustrate that although most boundary crossings probably fall within the realm of ethical practice, gray areas alert therapists that they are approaching a violation (Figure).20 Five factors have been found to increase psychiatrists’ vulnerability to boundary violations (Table 1).22

Figure Beware the ‘gray areas’ between boundary crossings, violations

Source: Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44. Republished with permission of the Association for the Advancement of PsychotherapyTable 1

Boundary violations: Factors that increase your vulnerability

| Life crises—effects of aging, career disappointments, unfulfilled hopes, or marital conflicts |

| Transitions—job changes or job loss |

| Medical illness |

| Arrogance—the belief that a boundary violation couldn’t happen to you and not recognizing the need for consultation |

| Stress points shared by the patient |

| Source: Reference 22 |

CASE CONTINUED: Board investigation

Dr. M’s relationship with Ms. Y grows intense, and he becomes increasingly concerned about her “clinginess.” After several months, Dr. M feels emotionally suffocated and ends the relationship. Despondent and suicidal, she seeks treatment in the local emergency room. Ms. Y tells the ER psychiatrist about her relationship with Dr. M and that she cannot go on without him in her life. The ER psychiatrist refers her to another psychiatrist for outpatient care, and, with Ms. Y’s permission, files a complaint about Dr. M with the state medical board and the district branch ethics committee.

The state medical board investigates Dr. M. He is contrite about his actions and their effect on Ms. Y. The state board refers Dr. M to an impaired physician’s program. He is required to attend a boundary violations course and undergo 1 year of practice supervision by a local psychiatrist. Several years later, Dr. M is doing well in his practice and has had no further complaints lodged against him.

Boundaries vs relationships. Using boundaries as a metaphor for maintaining the separation of therapist and patient was intended to serve the analytic process and to protect the patient’s welfare.2 Clearly, certain boundaries—such as sexual contact between psychiatrist and patient—must remain sacrosanct. Yet certain practices avoided in analysis may be appropriate for other therapeutic interventions. For example, whereas psychoanalysis has strict prohibitions against seeing patients anywhere except in the office, cognitive-behavioral therapists may find it useful to conduct sessions in public, or—under carefully arranged circumstances—even in a patient’s home. Other examples include accompanying a patient with agoraphobia to a public gathering or dining with a patient with anorexia.

Exercise caution when you decide to alter traditional boundaries. Even minor crossings that are not likely to progress to violations have the potential to contaminate the therapeutic relationship and place the psychiatrist on a “slippery slope” to patient exploitation.22,23 Some boundary issues are ambiguous, and extenuating circumstances can create a context that temporarily stretches a boundary beyond its normal limits,24 especially in small communities and rural settings where patients and treating psychiatrists are likely to know and encounter each other in social settings.25 Our recommendations for avoiding boundary violations appear in Table 2.

Except in clear cases of malfeasance, determining whether or not you have crossed a boundary is not a straightforward decision based on a single theoretical perspective or absolute standard.26 Regardless of whether a given boundary’s edge is well defined, 2 things are clear:

- unlike patients, psychiatrists have a professional code to honor27

- harm is determined by the meaning of the behavior to the patient and not the psychiatrist’s intentions.4

Table 2

Simple steps help avoid boundary violations

| Dos |

| Know your state’s statutes regarding medical ethics |

| Stay abreast of the American Psychiatric Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics |

| Consult with colleagues |

| Be aware of your weaknesses |

| Avoid ‘slippery slopes’ |

| Use objective documentation |

| Build a satisfying personal life |

| Don’ts |

| Don’t foster dependency |

| Don’t use patients for your own gratification |

| Don’t engage in extra-therapeutic contacts |

| Avoid physical contact |

| Don’t accept gifts or services |

Related Resources

- American Medical Association. Principles of medical ethics. www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

Disclosures

Drs. Marshall and Myers report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Teston is a speaker for Shire US, Inc.

1. Margison F. Boundary violations and psychotherapy. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1996;9(3):204-8.

2. Smith D, Fitzpatrick M. Patient-therapist boundary issues: an integrative review of theory and research. Prof Psychol Res Pr 1995;26(5):499-506.

3. Canadian Medical Association. Canadian Medical Association code of ethics. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 1996.

4. Sarkar S. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2004;10:312-20.

5. Radeen J. The debate continues: unique ethics for psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003;38:115-8.

6. American Psychiatric Association The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

7. Zur O. To cross or not to cross: do boundaries in therapy protect or harm? The Psychotherapy Bulletin 2004;39(3):27-32.

8. Spickard W, Swiggart W, Manley G, et al. A continuing medical education approach to improve sexual boundaries of physicians. Bull Menninger Clin 2008;72(1):38-53.

9. Morrison J, Morrison T. Psychiatrists disciplined by a state medical board. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:474-8.

10. Beecher L, Altchuler S. Sexual boundary violations. Minn Med 2005;88:42-4.

11. Dehlendorf C. Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA 1998;279(23):1883-8.

12. Garfinkel P, Dorian B, Sadavoy J, Bagby R. Boundary violations and departments of psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:764-70.

13. Gabbard G, Nadelson C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 1995;273(18):1445-9.

14. Nadelson C, Notman M. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med 2002;23:191-201.

15. Sarkar S, Adshead G. Ethics in forensic psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15:527-31.

16. Green S, Bloch S. Working in a flawed mental health care system: an ethical challenge. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(9):1378-83.

17. Reid W. Treating clinicians and expert testimony. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 1998;4(2):121-4.

18. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry code of ethics. Annotations to AACAP ethical code with special reference to evolving health care delivery and reimbursement systems. Washington, DC: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 1995.

19. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Available at: http://www.aapl.org/pdf/ETHICSGDLNS. pdf. Accessed June 3, 2008.

20. Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44.

21. Sheets V. Teach nurses how to maintain professional boundaries, recognize potential problems, and make better patient care decisions. Nurs Manage 2000;31(8):28-34.

22. Norris D, Gutheil T, Strasburger L. This couldn’t happen to me: boundary problems and sexual misconduct in the psychotherapy relationship. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:517-22.

23. Galletly C. Crossing professional boundaries in medicine: the slippery slope to patient sexual exploitation. Med J Aust 2004;181(7):380-3.

24. Gutheil T, Gabbard G. Misuses and misunderstandings of boundary theory in clinical and regulatory settings. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(3):409-14.

25. Simon R, Williams I. Maintaining treatment boundaries in small communities and rural areas. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1440-6.

26. Dvoskin J. Commentary: two sides to every story—the need for objectivity and evidence. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2005;33(4):482-3.

27. Gutheil T. Boundary issues and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract 2005;11(2):88-96.

Dr. M is facing financial challenges with his fledgling private practice and begins consulting at a weight loss clinic to supplement his income. He finds him-self attracted to Ms. Y, a weight-loss patient he is treating. They seem to click interpersonally, and he extends his office visits with her. Ms. Y clearly enjoys this extra attention, and Dr. M begins including personal disclosures in his conversations with her.

In his residency training, Dr. M was taught never to date a current or former patient, but he views this situation as different. Ms. Y is seeing him only for weight loss, and he rationalizes that he is providing her with medical care, not “psychiatric” care. On 2 occasions he gives her a limited quantity of benzodiazepines for mild anxiety, which he considers a transitory stress-related condition and not an “official” DSM-IV-TR disorder.

Eventually, Dr. M asks Ms. Y to dinner and she accepts. After they begin dating, he decides to transfer her to another clinic physician “just to be safe.”

Although many psychiatrists assume that psychiatrist/patient boundaries are well defined by ethical and legal standards, boundary issues are a complex and controversial aspect of clinical practice. Psychoanalysts initially defined psychiatrist/patient boundaries as a way of structuring the unique and intimate relationship that evolves during analysis.1,2 The introduction of other therapeutic techniques and changes in health care funding have combined to make psychiatrist/patient boundaries far more complex.

Boundary violations are about exploitation. Both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Canadian Medical Association warn members to “scrupulously avoid using the physician/patient relationship to gratify their own emotional, financial, and sexual needs.”3

Boundaries represent the edge of appropriate behavior and serve 2 important purposes:

- They separate the therapeutic relationship from social, sexual, romantic, and business relationships and from relationships that transform into caretaking of the psychiatrist by the patient.

- They structure the professional relationship in ways that maintain the identity and roles of the patient and the professional.4

Psychiatry’s unique dilemmas

As are all physicians, psychiatrists are governed by the 9 biomedical ethics set forth in the AMA’s Principles of Medical Ethics. The American Psychiatric Association (APA), however, acknowledges that psychiatry has a “broader set of moral and ethical problems and dilemmas” that are unique to and magnified by the mental health setting.5 The APA has adopted 39 standards in addition to those set forth by the AMA. The first standard captures the unique responsibilities inherent in the psychiatrist/ patient relationship: A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient (Box).6

Sexual contact with patients is inherently harmful to patients, always unethical, and usually illegal.7 The rate of sexual misconduct among psychiatrists is unknown. National Practitioner Data Bank information is not available to the general public.8 Based on literature reviews and data from individual states9,10 and government agencies,11 an estimated 6% to10% of psychiatrists have had inappropriate sexual relations with patients.12 Estimates of sexual misconduct by psychiatrists:

All physicians are required to practice in accordance with the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics. Because these guidelines can be difficult to interpret for psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association provides further guidance with The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. The following excerpts from annotations to the first 2 principles spell out the basic concepts underlying appropriate psychiatrist/patient boundaries:

‘A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient. The psychiatrist shall be ever vigilant about the impact that his or her conduct has upon the boundaries of the doctor/patient relationship, and thus upon the well-being of the patient. These requirements become particularly important because of the essentially private, highly personal, and sometimes intensely emotional nature of the relationship established with the psychiatrist.

‘The requirement that the physician conduct himself/herself with propriety in his or her profession and in all the actions of his or her life is especially important in the case of the psychiatrist because the patient tends to model his or her behavior after that of his or her psychiatrist by identification. Further, the necessary intensity of the treatment relationship may tend to activate sexual and other needs and fantasies on the part of both patient and psychiatrist, while weakening the objectivity necessary for control. Additionally, the inherent inequality in the doctor-patient relationship may lead to exploitation of the patient. Sexual activity with a current or former patient is unethical.’

Source: Reference 6

- increase if misconduct is based on patient complaints

- decrease if self-reports are used

- decrease even further if based on official investigations.4

American psychoanalyst Frieda Fromm-Reichman reportedly offered her colleagues a not-so-humorous admonition: “Don’t have sex with your patients; you will only disappoint them.”4

Nonsexual boundary violations—such as accepting gifts, entering into business arrangements, or trying to influence a patient’s political or religious beliefs or sexual orientation—occur more frequently than sexual misconduct.12 Although the impact of nonsexual violations generally is less serious, any relationship that coexists with the therapeutic relationship has the potential to impair your judgment and contaminate your ability to focus exclusively on your patient’s well-being.13 Be cautious about any decision that could affect the treatment relationship.14

Triangle relationships.Originally, this term referred to the patient/therapist/psychiatrist triad. The term now has a broader meaning that includes:

- encroachments into care by managed care companies and government regulatory agencies

- interactions with the patient’s family members

- providing psychiatric care in non-traditional settings such as schools or prisons

- serving as an expert witness.15

The framework of trust once considered a core feature of the psychiatrist/patient relationship is being undermined by a funding system that demands efficiency and economy.16 Recognizing that some settings sacrifice patients’ clinical needs to the interests of the organization, the APA’s Guidelines for Ethical Practice in Organized Settings stipulate that the psychiatrist must “strive to resolve these conflicts in a manner that is likely to be of greatest benefit to the patient” by (for example):

- informing a patient of financial incentives or penalties that limit your ability to provide appropriate treatment

- not with holding information the patient could use to make informed treatment decisions, including treatment options not provided by you.6

Psychiatrists who doubt that the system—such as a mental health clinic, hospital, or managed care contract provider or reviewer—upholds the standard of acceptable care have the “ethical responsibility” to improve the system.6

Another change in mental health care attempts to limit psychiatrists to “medication management” so that less expensive professionals can provide adjunctive therapies. The treating psychiatrist bears some responsibility, however, for the appropriateness of the patient’s therapeutic options.6 According to Reid,17 psychiatrists are responsible for knowing something about the care, treatment style, credentials, and even ethics of those with whom they share treatment or to whom they refer patients.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Code of Ethics addresses the unique challenges encountered when a patient’s opinions differ from those of parents and other authority figures, such as school staff. The AACAP standards consistently direct the psychiatrist to keep the child’s interest primary, explaining that “the child and adolescent psychiatrist may be called upon to participate in attempts to control or change the behavior of children or adolescents…[but] the child and adolescent psychiatrist will avoid acting solely as an agent of the parents, guardians, or agencies.”18

Another triangle can occur when a treating psychiatrist serves as an expert witness or other evaluator for forensic or disability purposes. The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL) recommends that psychiatrists avoid acting as expert witnesses for their patients or performing patient evaluations for legal purposes.19 While recognizing that certain situations may require a psychiatrist to serve a dual role, the AAPL stresses that sensitivity to differences between clinical and legal obligations remains important.

Avoid serving as an expert witness for your patient. The intrusion of another role into the doctor/patient relationship can alter the treatment process and permanently color future inter actions. Likewise, treating an individual whom you previously evaluated for forensic purposes raises similar concerns, including the possibility of a mercenary motivation. Even when no such motivation exists, these situations can create the appearance that you have conscripted a vulnerable individual into your practice.

Emerging trends

Crossings vs violations. Efforts to distinguish when an action is unethical or illegal have led some to differentiate boundary crossings from boundary violations. Unfortunately, the 2 terms continue to be used synonymously, which confuses rather than clarifies the issue:

- Boundary crossings are aimed at enhancing the therapist’s treatment efforts—such as a hug instead of a hand shake at the end of a particularly difficult treatment session.

- Boundary violations are invariably harmful and unethical because they serve the therapist’s needs rather than the patient’s needs or the therapeutic process.20

Rather than trying to differentiate between crossings and violations or to determine under what circumstances changing boundaries is acceptable, Sheets21 conceptualizes a boundary not as a line to cross, but as a continuum of behavior. Under-involvement is at one end, over-involvement at the other, and a “zone of helpfulness” is in the middle.

Glass uses a Venn diagram to illustrate that although most boundary crossings probably fall within the realm of ethical practice, gray areas alert therapists that they are approaching a violation (Figure).20 Five factors have been found to increase psychiatrists’ vulnerability to boundary violations (Table 1).22

Figure Beware the ‘gray areas’ between boundary crossings, violations

Source: Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44. Republished with permission of the Association for the Advancement of PsychotherapyTable 1

Boundary violations: Factors that increase your vulnerability

| Life crises—effects of aging, career disappointments, unfulfilled hopes, or marital conflicts |

| Transitions—job changes or job loss |

| Medical illness |

| Arrogance—the belief that a boundary violation couldn’t happen to you and not recognizing the need for consultation |

| Stress points shared by the patient |

| Source: Reference 22 |

CASE CONTINUED: Board investigation

Dr. M’s relationship with Ms. Y grows intense, and he becomes increasingly concerned about her “clinginess.” After several months, Dr. M feels emotionally suffocated and ends the relationship. Despondent and suicidal, she seeks treatment in the local emergency room. Ms. Y tells the ER psychiatrist about her relationship with Dr. M and that she cannot go on without him in her life. The ER psychiatrist refers her to another psychiatrist for outpatient care, and, with Ms. Y’s permission, files a complaint about Dr. M with the state medical board and the district branch ethics committee.

The state medical board investigates Dr. M. He is contrite about his actions and their effect on Ms. Y. The state board refers Dr. M to an impaired physician’s program. He is required to attend a boundary violations course and undergo 1 year of practice supervision by a local psychiatrist. Several years later, Dr. M is doing well in his practice and has had no further complaints lodged against him.

Boundaries vs relationships. Using boundaries as a metaphor for maintaining the separation of therapist and patient was intended to serve the analytic process and to protect the patient’s welfare.2 Clearly, certain boundaries—such as sexual contact between psychiatrist and patient—must remain sacrosanct. Yet certain practices avoided in analysis may be appropriate for other therapeutic interventions. For example, whereas psychoanalysis has strict prohibitions against seeing patients anywhere except in the office, cognitive-behavioral therapists may find it useful to conduct sessions in public, or—under carefully arranged circumstances—even in a patient’s home. Other examples include accompanying a patient with agoraphobia to a public gathering or dining with a patient with anorexia.

Exercise caution when you decide to alter traditional boundaries. Even minor crossings that are not likely to progress to violations have the potential to contaminate the therapeutic relationship and place the psychiatrist on a “slippery slope” to patient exploitation.22,23 Some boundary issues are ambiguous, and extenuating circumstances can create a context that temporarily stretches a boundary beyond its normal limits,24 especially in small communities and rural settings where patients and treating psychiatrists are likely to know and encounter each other in social settings.25 Our recommendations for avoiding boundary violations appear in Table 2.

Except in clear cases of malfeasance, determining whether or not you have crossed a boundary is not a straightforward decision based on a single theoretical perspective or absolute standard.26 Regardless of whether a given boundary’s edge is well defined, 2 things are clear:

- unlike patients, psychiatrists have a professional code to honor27

- harm is determined by the meaning of the behavior to the patient and not the psychiatrist’s intentions.4

Table 2

Simple steps help avoid boundary violations

| Dos |

| Know your state’s statutes regarding medical ethics |

| Stay abreast of the American Psychiatric Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics |

| Consult with colleagues |

| Be aware of your weaknesses |

| Avoid ‘slippery slopes’ |

| Use objective documentation |

| Build a satisfying personal life |

| Don’ts |

| Don’t foster dependency |

| Don’t use patients for your own gratification |

| Don’t engage in extra-therapeutic contacts |

| Avoid physical contact |

| Don’t accept gifts or services |

Related Resources

- American Medical Association. Principles of medical ethics. www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

Disclosures

Drs. Marshall and Myers report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Teston is a speaker for Shire US, Inc.

Dr. M is facing financial challenges with his fledgling private practice and begins consulting at a weight loss clinic to supplement his income. He finds him-self attracted to Ms. Y, a weight-loss patient he is treating. They seem to click interpersonally, and he extends his office visits with her. Ms. Y clearly enjoys this extra attention, and Dr. M begins including personal disclosures in his conversations with her.

In his residency training, Dr. M was taught never to date a current or former patient, but he views this situation as different. Ms. Y is seeing him only for weight loss, and he rationalizes that he is providing her with medical care, not “psychiatric” care. On 2 occasions he gives her a limited quantity of benzodiazepines for mild anxiety, which he considers a transitory stress-related condition and not an “official” DSM-IV-TR disorder.

Eventually, Dr. M asks Ms. Y to dinner and she accepts. After they begin dating, he decides to transfer her to another clinic physician “just to be safe.”

Although many psychiatrists assume that psychiatrist/patient boundaries are well defined by ethical and legal standards, boundary issues are a complex and controversial aspect of clinical practice. Psychoanalysts initially defined psychiatrist/patient boundaries as a way of structuring the unique and intimate relationship that evolves during analysis.1,2 The introduction of other therapeutic techniques and changes in health care funding have combined to make psychiatrist/patient boundaries far more complex.

Boundary violations are about exploitation. Both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Canadian Medical Association warn members to “scrupulously avoid using the physician/patient relationship to gratify their own emotional, financial, and sexual needs.”3

Boundaries represent the edge of appropriate behavior and serve 2 important purposes:

- They separate the therapeutic relationship from social, sexual, romantic, and business relationships and from relationships that transform into caretaking of the psychiatrist by the patient.

- They structure the professional relationship in ways that maintain the identity and roles of the patient and the professional.4

Psychiatry’s unique dilemmas

As are all physicians, psychiatrists are governed by the 9 biomedical ethics set forth in the AMA’s Principles of Medical Ethics. The American Psychiatric Association (APA), however, acknowledges that psychiatry has a “broader set of moral and ethical problems and dilemmas” that are unique to and magnified by the mental health setting.5 The APA has adopted 39 standards in addition to those set forth by the AMA. The first standard captures the unique responsibilities inherent in the psychiatrist/ patient relationship: A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient (Box).6

Sexual contact with patients is inherently harmful to patients, always unethical, and usually illegal.7 The rate of sexual misconduct among psychiatrists is unknown. National Practitioner Data Bank information is not available to the general public.8 Based on literature reviews and data from individual states9,10 and government agencies,11 an estimated 6% to10% of psychiatrists have had inappropriate sexual relations with patients.12 Estimates of sexual misconduct by psychiatrists:

All physicians are required to practice in accordance with the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics. Because these guidelines can be difficult to interpret for psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association provides further guidance with The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. The following excerpts from annotations to the first 2 principles spell out the basic concepts underlying appropriate psychiatrist/patient boundaries:

‘A psychiatrist shall not gratify his or her own needs by exploiting the patient. The psychiatrist shall be ever vigilant about the impact that his or her conduct has upon the boundaries of the doctor/patient relationship, and thus upon the well-being of the patient. These requirements become particularly important because of the essentially private, highly personal, and sometimes intensely emotional nature of the relationship established with the psychiatrist.

‘The requirement that the physician conduct himself/herself with propriety in his or her profession and in all the actions of his or her life is especially important in the case of the psychiatrist because the patient tends to model his or her behavior after that of his or her psychiatrist by identification. Further, the necessary intensity of the treatment relationship may tend to activate sexual and other needs and fantasies on the part of both patient and psychiatrist, while weakening the objectivity necessary for control. Additionally, the inherent inequality in the doctor-patient relationship may lead to exploitation of the patient. Sexual activity with a current or former patient is unethical.’

Source: Reference 6

- increase if misconduct is based on patient complaints

- decrease if self-reports are used

- decrease even further if based on official investigations.4

American psychoanalyst Frieda Fromm-Reichman reportedly offered her colleagues a not-so-humorous admonition: “Don’t have sex with your patients; you will only disappoint them.”4

Nonsexual boundary violations—such as accepting gifts, entering into business arrangements, or trying to influence a patient’s political or religious beliefs or sexual orientation—occur more frequently than sexual misconduct.12 Although the impact of nonsexual violations generally is less serious, any relationship that coexists with the therapeutic relationship has the potential to impair your judgment and contaminate your ability to focus exclusively on your patient’s well-being.13 Be cautious about any decision that could affect the treatment relationship.14

Triangle relationships.Originally, this term referred to the patient/therapist/psychiatrist triad. The term now has a broader meaning that includes:

- encroachments into care by managed care companies and government regulatory agencies

- interactions with the patient’s family members

- providing psychiatric care in non-traditional settings such as schools or prisons

- serving as an expert witness.15

The framework of trust once considered a core feature of the psychiatrist/patient relationship is being undermined by a funding system that demands efficiency and economy.16 Recognizing that some settings sacrifice patients’ clinical needs to the interests of the organization, the APA’s Guidelines for Ethical Practice in Organized Settings stipulate that the psychiatrist must “strive to resolve these conflicts in a manner that is likely to be of greatest benefit to the patient” by (for example):

- informing a patient of financial incentives or penalties that limit your ability to provide appropriate treatment

- not with holding information the patient could use to make informed treatment decisions, including treatment options not provided by you.6

Psychiatrists who doubt that the system—such as a mental health clinic, hospital, or managed care contract provider or reviewer—upholds the standard of acceptable care have the “ethical responsibility” to improve the system.6

Another change in mental health care attempts to limit psychiatrists to “medication management” so that less expensive professionals can provide adjunctive therapies. The treating psychiatrist bears some responsibility, however, for the appropriateness of the patient’s therapeutic options.6 According to Reid,17 psychiatrists are responsible for knowing something about the care, treatment style, credentials, and even ethics of those with whom they share treatment or to whom they refer patients.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Code of Ethics addresses the unique challenges encountered when a patient’s opinions differ from those of parents and other authority figures, such as school staff. The AACAP standards consistently direct the psychiatrist to keep the child’s interest primary, explaining that “the child and adolescent psychiatrist may be called upon to participate in attempts to control or change the behavior of children or adolescents…[but] the child and adolescent psychiatrist will avoid acting solely as an agent of the parents, guardians, or agencies.”18

Another triangle can occur when a treating psychiatrist serves as an expert witness or other evaluator for forensic or disability purposes. The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL) recommends that psychiatrists avoid acting as expert witnesses for their patients or performing patient evaluations for legal purposes.19 While recognizing that certain situations may require a psychiatrist to serve a dual role, the AAPL stresses that sensitivity to differences between clinical and legal obligations remains important.

Avoid serving as an expert witness for your patient. The intrusion of another role into the doctor/patient relationship can alter the treatment process and permanently color future inter actions. Likewise, treating an individual whom you previously evaluated for forensic purposes raises similar concerns, including the possibility of a mercenary motivation. Even when no such motivation exists, these situations can create the appearance that you have conscripted a vulnerable individual into your practice.

Emerging trends

Crossings vs violations. Efforts to distinguish when an action is unethical or illegal have led some to differentiate boundary crossings from boundary violations. Unfortunately, the 2 terms continue to be used synonymously, which confuses rather than clarifies the issue:

- Boundary crossings are aimed at enhancing the therapist’s treatment efforts—such as a hug instead of a hand shake at the end of a particularly difficult treatment session.

- Boundary violations are invariably harmful and unethical because they serve the therapist’s needs rather than the patient’s needs or the therapeutic process.20

Rather than trying to differentiate between crossings and violations or to determine under what circumstances changing boundaries is acceptable, Sheets21 conceptualizes a boundary not as a line to cross, but as a continuum of behavior. Under-involvement is at one end, over-involvement at the other, and a “zone of helpfulness” is in the middle.

Glass uses a Venn diagram to illustrate that although most boundary crossings probably fall within the realm of ethical practice, gray areas alert therapists that they are approaching a violation (Figure).20 Five factors have been found to increase psychiatrists’ vulnerability to boundary violations (Table 1).22

Figure Beware the ‘gray areas’ between boundary crossings, violations

Source: Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44. Republished with permission of the Association for the Advancement of PsychotherapyTable 1

Boundary violations: Factors that increase your vulnerability

| Life crises—effects of aging, career disappointments, unfulfilled hopes, or marital conflicts |

| Transitions—job changes or job loss |

| Medical illness |

| Arrogance—the belief that a boundary violation couldn’t happen to you and not recognizing the need for consultation |

| Stress points shared by the patient |

| Source: Reference 22 |

CASE CONTINUED: Board investigation

Dr. M’s relationship with Ms. Y grows intense, and he becomes increasingly concerned about her “clinginess.” After several months, Dr. M feels emotionally suffocated and ends the relationship. Despondent and suicidal, she seeks treatment in the local emergency room. Ms. Y tells the ER psychiatrist about her relationship with Dr. M and that she cannot go on without him in her life. The ER psychiatrist refers her to another psychiatrist for outpatient care, and, with Ms. Y’s permission, files a complaint about Dr. M with the state medical board and the district branch ethics committee.

The state medical board investigates Dr. M. He is contrite about his actions and their effect on Ms. Y. The state board refers Dr. M to an impaired physician’s program. He is required to attend a boundary violations course and undergo 1 year of practice supervision by a local psychiatrist. Several years later, Dr. M is doing well in his practice and has had no further complaints lodged against him.

Boundaries vs relationships. Using boundaries as a metaphor for maintaining the separation of therapist and patient was intended to serve the analytic process and to protect the patient’s welfare.2 Clearly, certain boundaries—such as sexual contact between psychiatrist and patient—must remain sacrosanct. Yet certain practices avoided in analysis may be appropriate for other therapeutic interventions. For example, whereas psychoanalysis has strict prohibitions against seeing patients anywhere except in the office, cognitive-behavioral therapists may find it useful to conduct sessions in public, or—under carefully arranged circumstances—even in a patient’s home. Other examples include accompanying a patient with agoraphobia to a public gathering or dining with a patient with anorexia.

Exercise caution when you decide to alter traditional boundaries. Even minor crossings that are not likely to progress to violations have the potential to contaminate the therapeutic relationship and place the psychiatrist on a “slippery slope” to patient exploitation.22,23 Some boundary issues are ambiguous, and extenuating circumstances can create a context that temporarily stretches a boundary beyond its normal limits,24 especially in small communities and rural settings where patients and treating psychiatrists are likely to know and encounter each other in social settings.25 Our recommendations for avoiding boundary violations appear in Table 2.

Except in clear cases of malfeasance, determining whether or not you have crossed a boundary is not a straightforward decision based on a single theoretical perspective or absolute standard.26 Regardless of whether a given boundary’s edge is well defined, 2 things are clear:

- unlike patients, psychiatrists have a professional code to honor27

- harm is determined by the meaning of the behavior to the patient and not the psychiatrist’s intentions.4

Table 2

Simple steps help avoid boundary violations

| Dos |

| Know your state’s statutes regarding medical ethics |

| Stay abreast of the American Psychiatric Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics |

| Consult with colleagues |

| Be aware of your weaknesses |

| Avoid ‘slippery slopes’ |

| Use objective documentation |

| Build a satisfying personal life |

| Don’ts |

| Don’t foster dependency |

| Don’t use patients for your own gratification |

| Don’t engage in extra-therapeutic contacts |

| Avoid physical contact |

| Don’t accept gifts or services |

Related Resources

- American Medical Association. Principles of medical ethics. www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

Disclosures

Drs. Marshall and Myers report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Teston is a speaker for Shire US, Inc.

1. Margison F. Boundary violations and psychotherapy. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1996;9(3):204-8.

2. Smith D, Fitzpatrick M. Patient-therapist boundary issues: an integrative review of theory and research. Prof Psychol Res Pr 1995;26(5):499-506.

3. Canadian Medical Association. Canadian Medical Association code of ethics. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 1996.

4. Sarkar S. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2004;10:312-20.

5. Radeen J. The debate continues: unique ethics for psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003;38:115-8.

6. American Psychiatric Association The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

7. Zur O. To cross or not to cross: do boundaries in therapy protect or harm? The Psychotherapy Bulletin 2004;39(3):27-32.

8. Spickard W, Swiggart W, Manley G, et al. A continuing medical education approach to improve sexual boundaries of physicians. Bull Menninger Clin 2008;72(1):38-53.

9. Morrison J, Morrison T. Psychiatrists disciplined by a state medical board. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:474-8.

10. Beecher L, Altchuler S. Sexual boundary violations. Minn Med 2005;88:42-4.

11. Dehlendorf C. Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA 1998;279(23):1883-8.

12. Garfinkel P, Dorian B, Sadavoy J, Bagby R. Boundary violations and departments of psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:764-70.

13. Gabbard G, Nadelson C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 1995;273(18):1445-9.

14. Nadelson C, Notman M. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med 2002;23:191-201.

15. Sarkar S, Adshead G. Ethics in forensic psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15:527-31.

16. Green S, Bloch S. Working in a flawed mental health care system: an ethical challenge. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(9):1378-83.

17. Reid W. Treating clinicians and expert testimony. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 1998;4(2):121-4.

18. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry code of ethics. Annotations to AACAP ethical code with special reference to evolving health care delivery and reimbursement systems. Washington, DC: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 1995.

19. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Available at: http://www.aapl.org/pdf/ETHICSGDLNS. pdf. Accessed June 3, 2008.

20. Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44.

21. Sheets V. Teach nurses how to maintain professional boundaries, recognize potential problems, and make better patient care decisions. Nurs Manage 2000;31(8):28-34.

22. Norris D, Gutheil T, Strasburger L. This couldn’t happen to me: boundary problems and sexual misconduct in the psychotherapy relationship. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:517-22.

23. Galletly C. Crossing professional boundaries in medicine: the slippery slope to patient sexual exploitation. Med J Aust 2004;181(7):380-3.

24. Gutheil T, Gabbard G. Misuses and misunderstandings of boundary theory in clinical and regulatory settings. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(3):409-14.

25. Simon R, Williams I. Maintaining treatment boundaries in small communities and rural areas. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1440-6.

26. Dvoskin J. Commentary: two sides to every story—the need for objectivity and evidence. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2005;33(4):482-3.

27. Gutheil T. Boundary issues and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract 2005;11(2):88-96.

1. Margison F. Boundary violations and psychotherapy. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1996;9(3):204-8.

2. Smith D, Fitzpatrick M. Patient-therapist boundary issues: an integrative review of theory and research. Prof Psychol Res Pr 1995;26(5):499-506.

3. Canadian Medical Association. Canadian Medical Association code of ethics. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 1996.

4. Sarkar S. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2004;10:312-20.

5. Radeen J. The debate continues: unique ethics for psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003;38:115-8.

6. American Psychiatric Association The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

7. Zur O. To cross or not to cross: do boundaries in therapy protect or harm? The Psychotherapy Bulletin 2004;39(3):27-32.

8. Spickard W, Swiggart W, Manley G, et al. A continuing medical education approach to improve sexual boundaries of physicians. Bull Menninger Clin 2008;72(1):38-53.

9. Morrison J, Morrison T. Psychiatrists disciplined by a state medical board. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:474-8.

10. Beecher L, Altchuler S. Sexual boundary violations. Minn Med 2005;88:42-4.

11. Dehlendorf C. Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA 1998;279(23):1883-8.

12. Garfinkel P, Dorian B, Sadavoy J, Bagby R. Boundary violations and departments of psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:764-70.

13. Gabbard G, Nadelson C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 1995;273(18):1445-9.

14. Nadelson C, Notman M. Boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship. Theor Med 2002;23:191-201.

15. Sarkar S, Adshead G. Ethics in forensic psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15:527-31.

16. Green S, Bloch S. Working in a flawed mental health care system: an ethical challenge. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(9):1378-83.

17. Reid W. Treating clinicians and expert testimony. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 1998;4(2):121-4.

18. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry code of ethics. Annotations to AACAP ethical code with special reference to evolving health care delivery and reimbursement systems. Washington, DC: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 1995.

19. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Available at: http://www.aapl.org/pdf/ETHICSGDLNS. pdf. Accessed June 3, 2008.

20. Glass L. The gray areas of boundary crossings and violations. Am J Psychother 2003;57(4):429-44.

21. Sheets V. Teach nurses how to maintain professional boundaries, recognize potential problems, and make better patient care decisions. Nurs Manage 2000;31(8):28-34.

22. Norris D, Gutheil T, Strasburger L. This couldn’t happen to me: boundary problems and sexual misconduct in the psychotherapy relationship. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:517-22.

23. Galletly C. Crossing professional boundaries in medicine: the slippery slope to patient sexual exploitation. Med J Aust 2004;181(7):380-3.

24. Gutheil T, Gabbard G. Misuses and misunderstandings of boundary theory in clinical and regulatory settings. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(3):409-14.

25. Simon R, Williams I. Maintaining treatment boundaries in small communities and rural areas. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1440-6.

26. Dvoskin J. Commentary: two sides to every story—the need for objectivity and evidence. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2005;33(4):482-3.

27. Gutheil T. Boundary issues and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract 2005;11(2):88-96.