User login

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

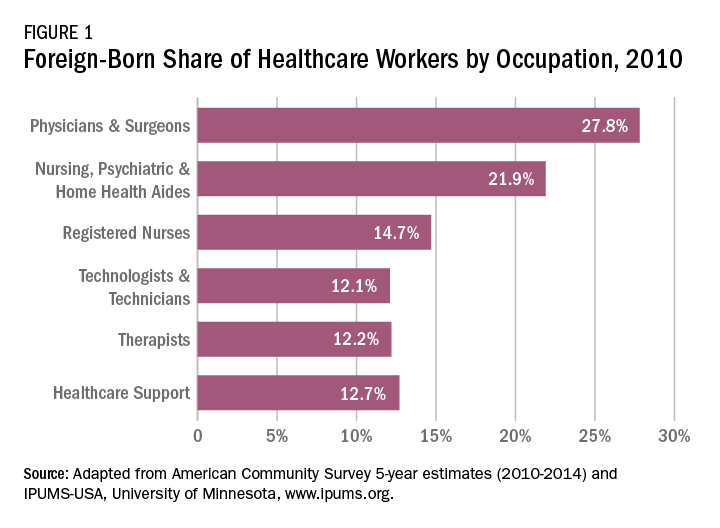

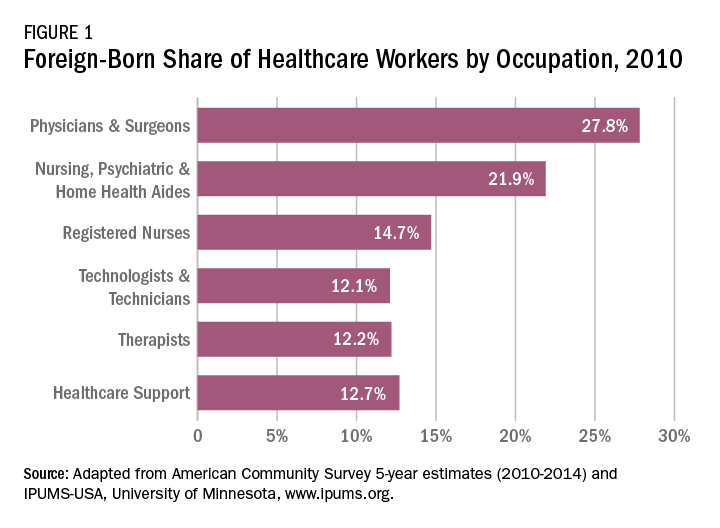

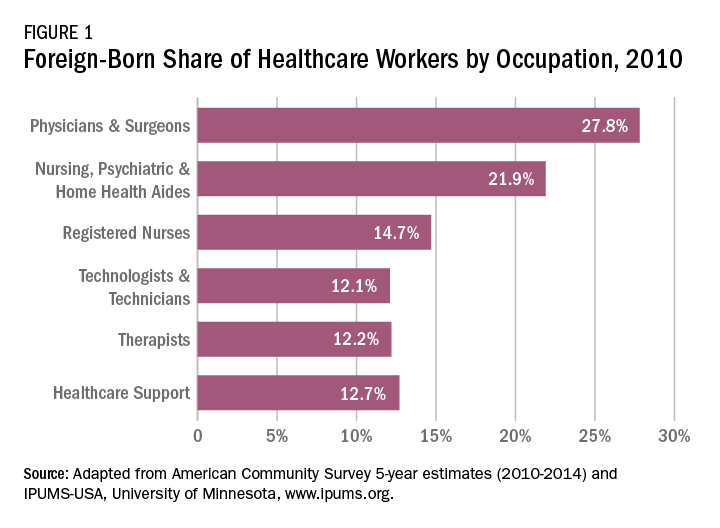

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).