User login

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

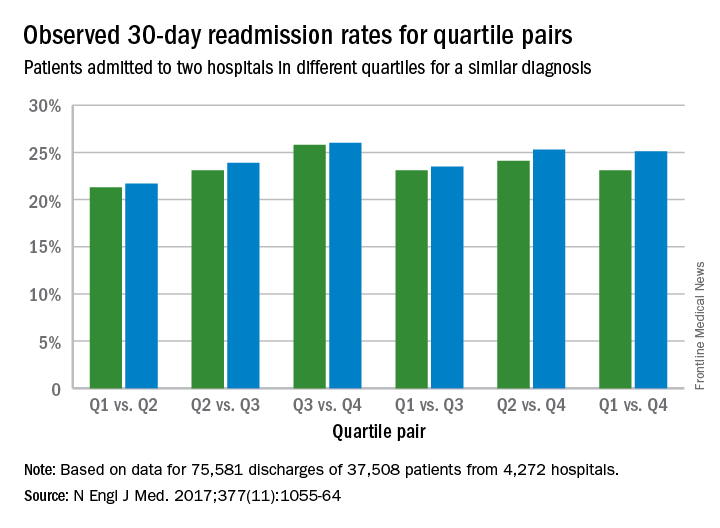

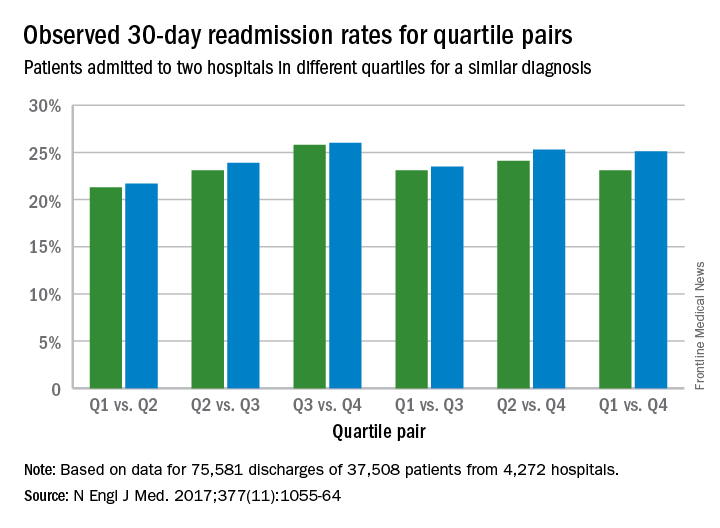

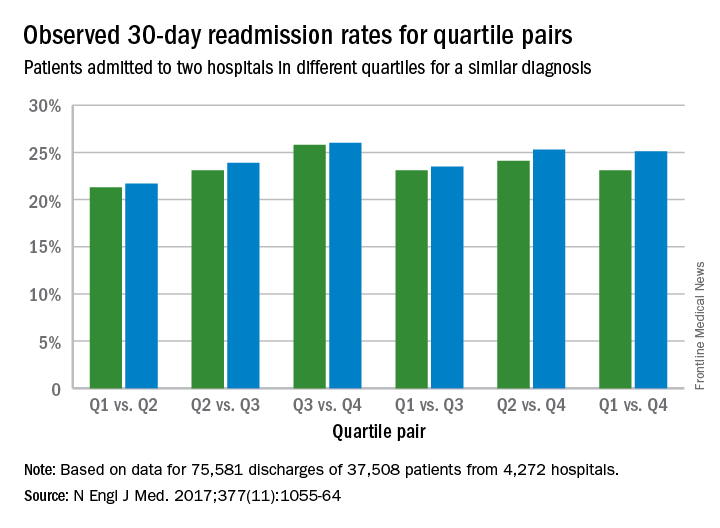

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points).

Data source: Analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data from July 2014 through June 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.