User login

Mr. W, age 45, is a divorced Army veteran living on the street who has entered alcohol treatment for the sixth time. He has never stayed sober for longer than 1 month after each of his previous treatment episodes.

On a typical day, Mr. W drinks 40 oz of beer, a pint of vodka, and other alcoholic beverages when available. Although he has used drugs, he reports that he did so only to augment the effects of alcohol. Before entering rehab, Mr. W worked for a television network for 16 years and was promoted to associate vice president. He lost that job as a result of drinking.

Mr. W comes from a large Irish Catholic family and has sustained an active religious faith, going to Mass 2 or 3 times a month. Throughout the interview, he appears introspective and describes frequent periods of “going inside” of himself to “rehash” things. He states that he has never been satisfied with his spiritual life and has been unable to “quiet the hunger inside.”

He describes his benders as “mini-retreats” and comments that focusing on the condensation droplets on a glass of beer is nearly a “sacramental experience” for him. He states: “My drinking is a spiritual thing for me. I believe that every time I drink I am on a spiritual search. I believe this with all my heart. I have this emptiness inside of me and alcohol would temporarily fill the enormous hole in my insides. Just for a short period of time, I would feel at peace and connected to others, and maybe even to God.”

Mr. W observes that “Every time I relapse it’s because I’m going through a spiritual withdrawal. Booze filled the void inside of me and now the void is back again. Physically and psychologically I’m fine. I’m just empty inside and when I can’t stand it any longer, I drink again.”

Few patients can so directly articulate the role they feel that spirituality plays in their substance use disorder. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the dynamics of spirituality and religion in the cause, maintenance, and treatment of substance misuse problems.

In this article, we discuss how spirituality can be assessed and suggest ethical and clinical practice concerns that we believe may support treatment of substance use disorder. We do not advocate incorporating spiritual interventions into clinical practice for patients who are uncomfortable with doing so, nor do we feel that consideration of and respect for patients’ spirituality precludes evidence-based pharmaceutical and behavioral treatment strategies. We believe, however, that addressing these issues can enhance treatment adherence in select patients.

Defining spirituality

Although religion and spirituality are related concepts, they differ.

- Religion has been defined as “an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols through which ones’ relationship to God or others is nurtured and exercised.”1

- Spirituality is more complex and multifaceted. Reflecting his extensive review of articles on spirituality and addiction, Cook2 proposed the following definition:

Spirituality is a distinctive, potentially creative, and universal dimension of

human experience arising within inner subjective awareness of individuals and within communities, social groups, and traditions. It may be experienced as relationship with that which is intimately “inner,” immanent, and personal, within the self and others, and/or as relationship with that which is wholly “other,” transcendent and beyond the self. It is experienced as being of fundamental or ultimate importance and is therefore concerned with matters of meaning and purpose in life, truth, and values.

In some religions, any use of alcohol or drugs is forbidden; in most religions, abuse of these substances violates norms. Those who misuse a substance also might be alienated from their religious and social support community. People struggling with addiction might feel they are compromising their spiritual values directly through the action itself and indirectly because of the harm their substance misuse causes to close friends and family. Misuse of substances also might be an attempt to “fill the void,” as Mr. W described it, of a spiritual longing or a consequence of doubts about meaning, purpose in life, and God.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that, among psychiatric disorders, substance abuse problems seem to be most associated with spiritual intervention—especially Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Cocaine Anonymous (CA). Many of the 12 steps contain references to God and spirituality. Although much of the evidence supporting the effectiveness of the spiritual components of AA/NA/CA is correlational,3,4 the resonance that many persons who are recovering from substance abuse find in the 12-step model suggests that spiritual issues are relevant to understanding patients’ viewpoints and for planning treatment.

Religion and spirituality in risk and recovery

Although alcohol and drugs can have positive religious significance (eg, wine in the Christian Eucharist or in the Hindu practice of Ayurvedic medicine; peyote in some indigenous American religious rituals), substance use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify themselves as highly religious or spiritual.5 Studies indicate that alcohol use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify as Jewish, Muslim, or conservative Protestant, compared with those who are Catholic or liberal Protestant.6

Research suggests that consideration and accommodation of religious and spiritual practices in the recovery process is effective7-9—and preferred—by many patients.10 Psychiatrists do not need to and, in many cases, should not deliver overtly spiritual treatments to patients recovering from substance abuse. Spirituality and religion are complex issues largely outside the expertise of psychiatry; it would be naïve to consider spirituality and religion as universally beneficial elements for all patients recovering from substance abuse. Instead, psychiatrists should be equipped to:

- assess for religion and spirituality in patients

- be aware of, and supportive of, resources for integrating spirituality into treatment (eg, clergy and hospital chaplains, local AA/NA/CA groups, community religious organizations, spirituality groups).

Assessment

Post and colleagues11 note: “When patients feel that their spiritual needs are neglected in standard clinical environments, many of them may be driven away from effective medical treatment.” This is of particular concern when working with persons who have a substance use disorder—among whom, regrettably, only a minority avail themselves of professional care. You should carefully gauge the importance of these dimensions in how patients understand their disorder and the components of treatment they think their recovery process should involve.

Asking about the religious and spiritual aspects of patients’ lives shows respect for their views and facilitates a therapeutic alliance by recognizing their autonomy in treatment. Pargament and Lomax12 state: “Religion speaks to highly sensitive issues that lie at the core of the individual’s identity, commitments, values and world view. Patients are unlikely to engage in a conversation about the deepest side of themselves unless their psychiatrist demonstrates an openness to, interest in, and appreciation of the patient’s religiousness.” This exploration process can suggest natural environmental support systems available to complement recovery efforts and can indicate whether consultation with a clergyperson knowledgeable about and sensitive to their particular religious tradition is appropriate.

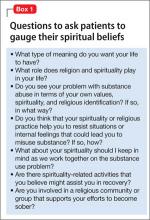

Assessment of spirituality and religious practice usually should occur during the initial clinical interview. Examples of revealing interview questions are listed in Box 1.

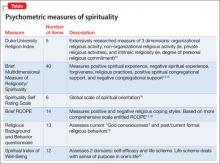

The Table13-20 lists well-researched psychometric measures that can provide clues to aspects of your patient’s spirituality. These scales yield quantitative results, yet it may be more useful to review with the patient his (her) responses to the items and to pursue issues further based on the responses.

In discussing responses to questions about their spirituality and religious practices, some patients might ask about your views and whether you agree with their views. You could respond with a direct, concise answer, but refocusing the discussion on why the topic of spirituality is important to understanding one’s life and choices might be more therapeutic. This also might be a good time to remind patients that the treatment plan should reflect their view of the role of religion and spirituality in their life.

Of course, some patients are disinclined to discuss spirituality or religion, or prefer that it not be considered in treatment. This is clearly a matter of patient choice, but be aware that the patient may change his (her) mind as the recovery process continues and that the topic can be revisited if desired.

Recommendations for practice

Give careful consideration to ethical and clinical practice issues related to spiritual components in the recovery process. Plante21 and Meador and Koenig1 addressed several relevant ethical principles in considering spirituality in, respectively, psychological and psychiatric practice. Delaney and co-workers22 also presented similar principles, specifically within the context of substance use treatment. These can be summarized as a series of recommendations:

- Although psychiatrists as a group typically have a lower rate of conventional spirituality and religious practice than many of their patients,23-25 it is important not to ignore the patient’s perspective and show respect for the patient’s spiritual needs. However, if the psychiatrist has strong personal religious beliefs, he (she) must carefully guard against proselytizing or exerting undue, unintentional influence.

- Given the variety of religious traditions in the United States, understanding their particular features, as with other issues of cultural diversity, requires competence and sensitivity. Your work requires study and consultation with knowledgeable peers and experts in various faith traditions. Clergy and clinically trained chaplains, in particular, can conduct more comprehensive spiritual assessments that can yield additional treatment-relevant information.

- Maintaining professional boundaries is critical when dealing with religious and spiritual aspects of the patient’s life and thinking. Keep in mind issues of transference and the authoritative influence of the psychiatrist. The patient should understand the difference between services offered by a mental health professional and those given by a spiritual counselor or member of the clergy. Spiritual and religious issues, such as addressing concerns over guilt and sin and a relationship with God, should be referred to an appropriate clergyperson.

- Spiritual interventions introduced into the therapeutic process always should derive from the patient’s perspective and value system; they should not be imposed from an external source.

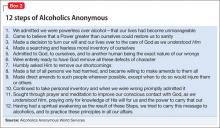

- Referral to AA often will help alcohol-dependent patients. The heart of AA’s philosophy is that addiction should be seen as a spiritual problem and that genuine recovery requires a profound spiritual awakening (Box 2). AA, as well as interventions inspired by it (eg, NA), are based on peer support, are readily available, and free. Although there is a dearth of controlled research demonstrating the efficacy of AA compared with other interventions, many recovering alcoholics credit these 12-step programs with their having maintained sobriety and adopting a positive lifestyle.

Recent research has identified specific components of AA participation that seem to be helpful.26 These include activities that are spiritual in nature and other generally active components of substance abuse care. Patient preference should be respected when encouraging AA involvement. For patients who are uncomfortable with AA—especially with its emphasis on spirituality—alternative peer support groups are available, such as SMART Recovery.27,28 If the patient adopts AA’s philosophy, it might be helpful for you to employ the language of AA and its constructs when talking with him (her).

Useful strategies on how therapists can encourage AA participation and integrate mutual help groups into treatment planning are described by Nowinski.25 Some AA members believe that use of medication is antithetical to the recovery process, but this is not the position of AA29; using FDA-approved medications, such as naltrexone and acamprosate, is evidence-based and often should be a part of the treatment regimen for alcohol dependence.

Bottom Line

Awareness of, and sensitivity to, the religious and spiritual characteristics of patients with substance use disorder can enhance clinical rapport, inform development of individualized treatment plans, and suggest strategies, such as professional consultation, that might increase the prospects for successful treatment.

Related Resources

- Galanter M. The concept of spirituality in relation to addiction recovery and general psychiatry. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2008;18:125-140.

- Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1345-1357.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

John P. Allen, PhD, MPA, discusses whether spirituality plays a different role in treating substance use disorder than it might in treating other psychiatric illnesses. Dr. Allen works at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Division of Addictions Research and Treatment, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina.

1. Meador KG, Koenig HG. Spirituality and religion in psychiatry practice: parameters and implications. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):549-555.

2. Cook CC. Addiction and spirituality. Addiction. 2004;99(5):539-551.

3. Kelly J, Stout RL, Magill M, et al. Spirituality in recovery: a lagged mediational analysis of alcoholics anonymous’ principal theoretical mechanism of behavior change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(3):454-463.

4. Zemore SE. A role for spiritual change in the benefits of 12-step involvement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(10 suppl):76s-79s.

5. Kendler KS, Liu XQ, Gardner CO, et al. Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496-503.

6. Koenig HG, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

7. Carter TM. The effects of spiritual practices on recovery from substance abuse. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1998; 5(5):409-413.

8. Conner BT, Anglin MD, Annon J, et al. Effect of religiosity and spirituality on drug treatment outcomes. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(2):189-198.

9. Robinson EA, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, et al. Six-month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(4):660-668.

10. Heinz AJ, Disney ER, Epstein DH, et al. A focus-group study on spirituality and substance-user treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(1-2):134-153.

11. Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(7):578-583.

12. Pargament KI, Lomax JW. Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):26-32.

13. Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78-85.

14. Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality: 1999. http://www.primarycarecore.org/PDF/137.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

15. Johnstone B, Yoon DP, Franklin KL, et al. Re-conceptualizing the factor structure of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality. J Relig Health. 2009;48(2):146-163.

16. Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, et al. Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):257-264.

17. Pargament K, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2(1):51-76.

18. Afterdeployment.org. Spirituality assessment. http://www.afterdeployment.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/assessment-tools/spirituality-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

19. Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90-96.

20. Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: a new Instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):499-503.

21. Plante TG. Integrating spirituality and psychotherapy: ethical issues and principles to consider. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(9):891-902.

22. Delaney HD, Forcehimes AA, Campbell WP, et al. Integrating spirituality into alcohol treatment. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(2):185-198.

23. Shafranske EP. Religious involvement and professional practices of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):525-532.

24. Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, et al. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):629-634.

25. Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, et al. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(9):1193-1198.

26. Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL, et al. Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: a multiple mediator analysis. Addiction. 2012;107(2):289-299.

27. Nowinski J. Self-help groups for addictions. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, eds. Addictions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999:328-346.

28. SMART recovery: self-management and recovery training. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed January 9, 2014.

29. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. The AA member—medication & other drugs. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 2011.

Mr. W, age 45, is a divorced Army veteran living on the street who has entered alcohol treatment for the sixth time. He has never stayed sober for longer than 1 month after each of his previous treatment episodes.

On a typical day, Mr. W drinks 40 oz of beer, a pint of vodka, and other alcoholic beverages when available. Although he has used drugs, he reports that he did so only to augment the effects of alcohol. Before entering rehab, Mr. W worked for a television network for 16 years and was promoted to associate vice president. He lost that job as a result of drinking.

Mr. W comes from a large Irish Catholic family and has sustained an active religious faith, going to Mass 2 or 3 times a month. Throughout the interview, he appears introspective and describes frequent periods of “going inside” of himself to “rehash” things. He states that he has never been satisfied with his spiritual life and has been unable to “quiet the hunger inside.”

He describes his benders as “mini-retreats” and comments that focusing on the condensation droplets on a glass of beer is nearly a “sacramental experience” for him. He states: “My drinking is a spiritual thing for me. I believe that every time I drink I am on a spiritual search. I believe this with all my heart. I have this emptiness inside of me and alcohol would temporarily fill the enormous hole in my insides. Just for a short period of time, I would feel at peace and connected to others, and maybe even to God.”

Mr. W observes that “Every time I relapse it’s because I’m going through a spiritual withdrawal. Booze filled the void inside of me and now the void is back again. Physically and psychologically I’m fine. I’m just empty inside and when I can’t stand it any longer, I drink again.”

Few patients can so directly articulate the role they feel that spirituality plays in their substance use disorder. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the dynamics of spirituality and religion in the cause, maintenance, and treatment of substance misuse problems.

In this article, we discuss how spirituality can be assessed and suggest ethical and clinical practice concerns that we believe may support treatment of substance use disorder. We do not advocate incorporating spiritual interventions into clinical practice for patients who are uncomfortable with doing so, nor do we feel that consideration of and respect for patients’ spirituality precludes evidence-based pharmaceutical and behavioral treatment strategies. We believe, however, that addressing these issues can enhance treatment adherence in select patients.

Defining spirituality

Although religion and spirituality are related concepts, they differ.

- Religion has been defined as “an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols through which ones’ relationship to God or others is nurtured and exercised.”1

- Spirituality is more complex and multifaceted. Reflecting his extensive review of articles on spirituality and addiction, Cook2 proposed the following definition:

Spirituality is a distinctive, potentially creative, and universal dimension of

human experience arising within inner subjective awareness of individuals and within communities, social groups, and traditions. It may be experienced as relationship with that which is intimately “inner,” immanent, and personal, within the self and others, and/or as relationship with that which is wholly “other,” transcendent and beyond the self. It is experienced as being of fundamental or ultimate importance and is therefore concerned with matters of meaning and purpose in life, truth, and values.

In some religions, any use of alcohol or drugs is forbidden; in most religions, abuse of these substances violates norms. Those who misuse a substance also might be alienated from their religious and social support community. People struggling with addiction might feel they are compromising their spiritual values directly through the action itself and indirectly because of the harm their substance misuse causes to close friends and family. Misuse of substances also might be an attempt to “fill the void,” as Mr. W described it, of a spiritual longing or a consequence of doubts about meaning, purpose in life, and God.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that, among psychiatric disorders, substance abuse problems seem to be most associated with spiritual intervention—especially Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Cocaine Anonymous (CA). Many of the 12 steps contain references to God and spirituality. Although much of the evidence supporting the effectiveness of the spiritual components of AA/NA/CA is correlational,3,4 the resonance that many persons who are recovering from substance abuse find in the 12-step model suggests that spiritual issues are relevant to understanding patients’ viewpoints and for planning treatment.

Religion and spirituality in risk and recovery

Although alcohol and drugs can have positive religious significance (eg, wine in the Christian Eucharist or in the Hindu practice of Ayurvedic medicine; peyote in some indigenous American religious rituals), substance use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify themselves as highly religious or spiritual.5 Studies indicate that alcohol use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify as Jewish, Muslim, or conservative Protestant, compared with those who are Catholic or liberal Protestant.6

Research suggests that consideration and accommodation of religious and spiritual practices in the recovery process is effective7-9—and preferred—by many patients.10 Psychiatrists do not need to and, in many cases, should not deliver overtly spiritual treatments to patients recovering from substance abuse. Spirituality and religion are complex issues largely outside the expertise of psychiatry; it would be naïve to consider spirituality and religion as universally beneficial elements for all patients recovering from substance abuse. Instead, psychiatrists should be equipped to:

- assess for religion and spirituality in patients

- be aware of, and supportive of, resources for integrating spirituality into treatment (eg, clergy and hospital chaplains, local AA/NA/CA groups, community religious organizations, spirituality groups).

Assessment

Post and colleagues11 note: “When patients feel that their spiritual needs are neglected in standard clinical environments, many of them may be driven away from effective medical treatment.” This is of particular concern when working with persons who have a substance use disorder—among whom, regrettably, only a minority avail themselves of professional care. You should carefully gauge the importance of these dimensions in how patients understand their disorder and the components of treatment they think their recovery process should involve.

Asking about the religious and spiritual aspects of patients’ lives shows respect for their views and facilitates a therapeutic alliance by recognizing their autonomy in treatment. Pargament and Lomax12 state: “Religion speaks to highly sensitive issues that lie at the core of the individual’s identity, commitments, values and world view. Patients are unlikely to engage in a conversation about the deepest side of themselves unless their psychiatrist demonstrates an openness to, interest in, and appreciation of the patient’s religiousness.” This exploration process can suggest natural environmental support systems available to complement recovery efforts and can indicate whether consultation with a clergyperson knowledgeable about and sensitive to their particular religious tradition is appropriate.

Assessment of spirituality and religious practice usually should occur during the initial clinical interview. Examples of revealing interview questions are listed in Box 1.

The Table13-20 lists well-researched psychometric measures that can provide clues to aspects of your patient’s spirituality. These scales yield quantitative results, yet it may be more useful to review with the patient his (her) responses to the items and to pursue issues further based on the responses.

In discussing responses to questions about their spirituality and religious practices, some patients might ask about your views and whether you agree with their views. You could respond with a direct, concise answer, but refocusing the discussion on why the topic of spirituality is important to understanding one’s life and choices might be more therapeutic. This also might be a good time to remind patients that the treatment plan should reflect their view of the role of religion and spirituality in their life.

Of course, some patients are disinclined to discuss spirituality or religion, or prefer that it not be considered in treatment. This is clearly a matter of patient choice, but be aware that the patient may change his (her) mind as the recovery process continues and that the topic can be revisited if desired.

Recommendations for practice

Give careful consideration to ethical and clinical practice issues related to spiritual components in the recovery process. Plante21 and Meador and Koenig1 addressed several relevant ethical principles in considering spirituality in, respectively, psychological and psychiatric practice. Delaney and co-workers22 also presented similar principles, specifically within the context of substance use treatment. These can be summarized as a series of recommendations:

- Although psychiatrists as a group typically have a lower rate of conventional spirituality and religious practice than many of their patients,23-25 it is important not to ignore the patient’s perspective and show respect for the patient’s spiritual needs. However, if the psychiatrist has strong personal religious beliefs, he (she) must carefully guard against proselytizing or exerting undue, unintentional influence.

- Given the variety of religious traditions in the United States, understanding their particular features, as with other issues of cultural diversity, requires competence and sensitivity. Your work requires study and consultation with knowledgeable peers and experts in various faith traditions. Clergy and clinically trained chaplains, in particular, can conduct more comprehensive spiritual assessments that can yield additional treatment-relevant information.

- Maintaining professional boundaries is critical when dealing with religious and spiritual aspects of the patient’s life and thinking. Keep in mind issues of transference and the authoritative influence of the psychiatrist. The patient should understand the difference between services offered by a mental health professional and those given by a spiritual counselor or member of the clergy. Spiritual and religious issues, such as addressing concerns over guilt and sin and a relationship with God, should be referred to an appropriate clergyperson.

- Spiritual interventions introduced into the therapeutic process always should derive from the patient’s perspective and value system; they should not be imposed from an external source.

- Referral to AA often will help alcohol-dependent patients. The heart of AA’s philosophy is that addiction should be seen as a spiritual problem and that genuine recovery requires a profound spiritual awakening (Box 2). AA, as well as interventions inspired by it (eg, NA), are based on peer support, are readily available, and free. Although there is a dearth of controlled research demonstrating the efficacy of AA compared with other interventions, many recovering alcoholics credit these 12-step programs with their having maintained sobriety and adopting a positive lifestyle.

Recent research has identified specific components of AA participation that seem to be helpful.26 These include activities that are spiritual in nature and other generally active components of substance abuse care. Patient preference should be respected when encouraging AA involvement. For patients who are uncomfortable with AA—especially with its emphasis on spirituality—alternative peer support groups are available, such as SMART Recovery.27,28 If the patient adopts AA’s philosophy, it might be helpful for you to employ the language of AA and its constructs when talking with him (her).

Useful strategies on how therapists can encourage AA participation and integrate mutual help groups into treatment planning are described by Nowinski.25 Some AA members believe that use of medication is antithetical to the recovery process, but this is not the position of AA29; using FDA-approved medications, such as naltrexone and acamprosate, is evidence-based and often should be a part of the treatment regimen for alcohol dependence.

Bottom Line

Awareness of, and sensitivity to, the religious and spiritual characteristics of patients with substance use disorder can enhance clinical rapport, inform development of individualized treatment plans, and suggest strategies, such as professional consultation, that might increase the prospects for successful treatment.

Related Resources

- Galanter M. The concept of spirituality in relation to addiction recovery and general psychiatry. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2008;18:125-140.

- Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1345-1357.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

John P. Allen, PhD, MPA, discusses whether spirituality plays a different role in treating substance use disorder than it might in treating other psychiatric illnesses. Dr. Allen works at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Division of Addictions Research and Treatment, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina.

Mr. W, age 45, is a divorced Army veteran living on the street who has entered alcohol treatment for the sixth time. He has never stayed sober for longer than 1 month after each of his previous treatment episodes.

On a typical day, Mr. W drinks 40 oz of beer, a pint of vodka, and other alcoholic beverages when available. Although he has used drugs, he reports that he did so only to augment the effects of alcohol. Before entering rehab, Mr. W worked for a television network for 16 years and was promoted to associate vice president. He lost that job as a result of drinking.

Mr. W comes from a large Irish Catholic family and has sustained an active religious faith, going to Mass 2 or 3 times a month. Throughout the interview, he appears introspective and describes frequent periods of “going inside” of himself to “rehash” things. He states that he has never been satisfied with his spiritual life and has been unable to “quiet the hunger inside.”

He describes his benders as “mini-retreats” and comments that focusing on the condensation droplets on a glass of beer is nearly a “sacramental experience” for him. He states: “My drinking is a spiritual thing for me. I believe that every time I drink I am on a spiritual search. I believe this with all my heart. I have this emptiness inside of me and alcohol would temporarily fill the enormous hole in my insides. Just for a short period of time, I would feel at peace and connected to others, and maybe even to God.”

Mr. W observes that “Every time I relapse it’s because I’m going through a spiritual withdrawal. Booze filled the void inside of me and now the void is back again. Physically and psychologically I’m fine. I’m just empty inside and when I can’t stand it any longer, I drink again.”

Few patients can so directly articulate the role they feel that spirituality plays in their substance use disorder. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the dynamics of spirituality and religion in the cause, maintenance, and treatment of substance misuse problems.

In this article, we discuss how spirituality can be assessed and suggest ethical and clinical practice concerns that we believe may support treatment of substance use disorder. We do not advocate incorporating spiritual interventions into clinical practice for patients who are uncomfortable with doing so, nor do we feel that consideration of and respect for patients’ spirituality precludes evidence-based pharmaceutical and behavioral treatment strategies. We believe, however, that addressing these issues can enhance treatment adherence in select patients.

Defining spirituality

Although religion and spirituality are related concepts, they differ.

- Religion has been defined as “an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols through which ones’ relationship to God or others is nurtured and exercised.”1

- Spirituality is more complex and multifaceted. Reflecting his extensive review of articles on spirituality and addiction, Cook2 proposed the following definition:

Spirituality is a distinctive, potentially creative, and universal dimension of

human experience arising within inner subjective awareness of individuals and within communities, social groups, and traditions. It may be experienced as relationship with that which is intimately “inner,” immanent, and personal, within the self and others, and/or as relationship with that which is wholly “other,” transcendent and beyond the self. It is experienced as being of fundamental or ultimate importance and is therefore concerned with matters of meaning and purpose in life, truth, and values.

In some religions, any use of alcohol or drugs is forbidden; in most religions, abuse of these substances violates norms. Those who misuse a substance also might be alienated from their religious and social support community. People struggling with addiction might feel they are compromising their spiritual values directly through the action itself and indirectly because of the harm their substance misuse causes to close friends and family. Misuse of substances also might be an attempt to “fill the void,” as Mr. W described it, of a spiritual longing or a consequence of doubts about meaning, purpose in life, and God.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that, among psychiatric disorders, substance abuse problems seem to be most associated with spiritual intervention—especially Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Cocaine Anonymous (CA). Many of the 12 steps contain references to God and spirituality. Although much of the evidence supporting the effectiveness of the spiritual components of AA/NA/CA is correlational,3,4 the resonance that many persons who are recovering from substance abuse find in the 12-step model suggests that spiritual issues are relevant to understanding patients’ viewpoints and for planning treatment.

Religion and spirituality in risk and recovery

Although alcohol and drugs can have positive religious significance (eg, wine in the Christian Eucharist or in the Hindu practice of Ayurvedic medicine; peyote in some indigenous American religious rituals), substance use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify themselves as highly religious or spiritual.5 Studies indicate that alcohol use and abuse are less prevalent among persons who identify as Jewish, Muslim, or conservative Protestant, compared with those who are Catholic or liberal Protestant.6

Research suggests that consideration and accommodation of religious and spiritual practices in the recovery process is effective7-9—and preferred—by many patients.10 Psychiatrists do not need to and, in many cases, should not deliver overtly spiritual treatments to patients recovering from substance abuse. Spirituality and religion are complex issues largely outside the expertise of psychiatry; it would be naïve to consider spirituality and religion as universally beneficial elements for all patients recovering from substance abuse. Instead, psychiatrists should be equipped to:

- assess for religion and spirituality in patients

- be aware of, and supportive of, resources for integrating spirituality into treatment (eg, clergy and hospital chaplains, local AA/NA/CA groups, community religious organizations, spirituality groups).

Assessment

Post and colleagues11 note: “When patients feel that their spiritual needs are neglected in standard clinical environments, many of them may be driven away from effective medical treatment.” This is of particular concern when working with persons who have a substance use disorder—among whom, regrettably, only a minority avail themselves of professional care. You should carefully gauge the importance of these dimensions in how patients understand their disorder and the components of treatment they think their recovery process should involve.

Asking about the religious and spiritual aspects of patients’ lives shows respect for their views and facilitates a therapeutic alliance by recognizing their autonomy in treatment. Pargament and Lomax12 state: “Religion speaks to highly sensitive issues that lie at the core of the individual’s identity, commitments, values and world view. Patients are unlikely to engage in a conversation about the deepest side of themselves unless their psychiatrist demonstrates an openness to, interest in, and appreciation of the patient’s religiousness.” This exploration process can suggest natural environmental support systems available to complement recovery efforts and can indicate whether consultation with a clergyperson knowledgeable about and sensitive to their particular religious tradition is appropriate.

Assessment of spirituality and religious practice usually should occur during the initial clinical interview. Examples of revealing interview questions are listed in Box 1.

The Table13-20 lists well-researched psychometric measures that can provide clues to aspects of your patient’s spirituality. These scales yield quantitative results, yet it may be more useful to review with the patient his (her) responses to the items and to pursue issues further based on the responses.

In discussing responses to questions about their spirituality and religious practices, some patients might ask about your views and whether you agree with their views. You could respond with a direct, concise answer, but refocusing the discussion on why the topic of spirituality is important to understanding one’s life and choices might be more therapeutic. This also might be a good time to remind patients that the treatment plan should reflect their view of the role of religion and spirituality in their life.

Of course, some patients are disinclined to discuss spirituality or religion, or prefer that it not be considered in treatment. This is clearly a matter of patient choice, but be aware that the patient may change his (her) mind as the recovery process continues and that the topic can be revisited if desired.

Recommendations for practice

Give careful consideration to ethical and clinical practice issues related to spiritual components in the recovery process. Plante21 and Meador and Koenig1 addressed several relevant ethical principles in considering spirituality in, respectively, psychological and psychiatric practice. Delaney and co-workers22 also presented similar principles, specifically within the context of substance use treatment. These can be summarized as a series of recommendations:

- Although psychiatrists as a group typically have a lower rate of conventional spirituality and religious practice than many of their patients,23-25 it is important not to ignore the patient’s perspective and show respect for the patient’s spiritual needs. However, if the psychiatrist has strong personal religious beliefs, he (she) must carefully guard against proselytizing or exerting undue, unintentional influence.

- Given the variety of religious traditions in the United States, understanding their particular features, as with other issues of cultural diversity, requires competence and sensitivity. Your work requires study and consultation with knowledgeable peers and experts in various faith traditions. Clergy and clinically trained chaplains, in particular, can conduct more comprehensive spiritual assessments that can yield additional treatment-relevant information.

- Maintaining professional boundaries is critical when dealing with religious and spiritual aspects of the patient’s life and thinking. Keep in mind issues of transference and the authoritative influence of the psychiatrist. The patient should understand the difference between services offered by a mental health professional and those given by a spiritual counselor or member of the clergy. Spiritual and religious issues, such as addressing concerns over guilt and sin and a relationship with God, should be referred to an appropriate clergyperson.

- Spiritual interventions introduced into the therapeutic process always should derive from the patient’s perspective and value system; they should not be imposed from an external source.

- Referral to AA often will help alcohol-dependent patients. The heart of AA’s philosophy is that addiction should be seen as a spiritual problem and that genuine recovery requires a profound spiritual awakening (Box 2). AA, as well as interventions inspired by it (eg, NA), are based on peer support, are readily available, and free. Although there is a dearth of controlled research demonstrating the efficacy of AA compared with other interventions, many recovering alcoholics credit these 12-step programs with their having maintained sobriety and adopting a positive lifestyle.

Recent research has identified specific components of AA participation that seem to be helpful.26 These include activities that are spiritual in nature and other generally active components of substance abuse care. Patient preference should be respected when encouraging AA involvement. For patients who are uncomfortable with AA—especially with its emphasis on spirituality—alternative peer support groups are available, such as SMART Recovery.27,28 If the patient adopts AA’s philosophy, it might be helpful for you to employ the language of AA and its constructs when talking with him (her).

Useful strategies on how therapists can encourage AA participation and integrate mutual help groups into treatment planning are described by Nowinski.25 Some AA members believe that use of medication is antithetical to the recovery process, but this is not the position of AA29; using FDA-approved medications, such as naltrexone and acamprosate, is evidence-based and often should be a part of the treatment regimen for alcohol dependence.

Bottom Line

Awareness of, and sensitivity to, the religious and spiritual characteristics of patients with substance use disorder can enhance clinical rapport, inform development of individualized treatment plans, and suggest strategies, such as professional consultation, that might increase the prospects for successful treatment.

Related Resources

- Galanter M. The concept of spirituality in relation to addiction recovery and general psychiatry. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2008;18:125-140.

- Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1345-1357.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

John P. Allen, PhD, MPA, discusses whether spirituality plays a different role in treating substance use disorder than it might in treating other psychiatric illnesses. Dr. Allen works at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Division of Addictions Research and Treatment, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina.

1. Meador KG, Koenig HG. Spirituality and religion in psychiatry practice: parameters and implications. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):549-555.

2. Cook CC. Addiction and spirituality. Addiction. 2004;99(5):539-551.

3. Kelly J, Stout RL, Magill M, et al. Spirituality in recovery: a lagged mediational analysis of alcoholics anonymous’ principal theoretical mechanism of behavior change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(3):454-463.

4. Zemore SE. A role for spiritual change in the benefits of 12-step involvement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(10 suppl):76s-79s.

5. Kendler KS, Liu XQ, Gardner CO, et al. Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496-503.

6. Koenig HG, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

7. Carter TM. The effects of spiritual practices on recovery from substance abuse. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1998; 5(5):409-413.

8. Conner BT, Anglin MD, Annon J, et al. Effect of religiosity and spirituality on drug treatment outcomes. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(2):189-198.

9. Robinson EA, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, et al. Six-month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(4):660-668.

10. Heinz AJ, Disney ER, Epstein DH, et al. A focus-group study on spirituality and substance-user treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(1-2):134-153.

11. Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(7):578-583.

12. Pargament KI, Lomax JW. Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):26-32.

13. Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78-85.

14. Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality: 1999. http://www.primarycarecore.org/PDF/137.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

15. Johnstone B, Yoon DP, Franklin KL, et al. Re-conceptualizing the factor structure of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality. J Relig Health. 2009;48(2):146-163.

16. Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, et al. Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):257-264.

17. Pargament K, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2(1):51-76.

18. Afterdeployment.org. Spirituality assessment. http://www.afterdeployment.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/assessment-tools/spirituality-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

19. Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90-96.

20. Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: a new Instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):499-503.

21. Plante TG. Integrating spirituality and psychotherapy: ethical issues and principles to consider. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(9):891-902.

22. Delaney HD, Forcehimes AA, Campbell WP, et al. Integrating spirituality into alcohol treatment. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(2):185-198.

23. Shafranske EP. Religious involvement and professional practices of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):525-532.

24. Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, et al. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):629-634.

25. Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, et al. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(9):1193-1198.

26. Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL, et al. Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: a multiple mediator analysis. Addiction. 2012;107(2):289-299.

27. Nowinski J. Self-help groups for addictions. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, eds. Addictions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999:328-346.

28. SMART recovery: self-management and recovery training. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed January 9, 2014.

29. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. The AA member—medication & other drugs. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 2011.

1. Meador KG, Koenig HG. Spirituality and religion in psychiatry practice: parameters and implications. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):549-555.

2. Cook CC. Addiction and spirituality. Addiction. 2004;99(5):539-551.

3. Kelly J, Stout RL, Magill M, et al. Spirituality in recovery: a lagged mediational analysis of alcoholics anonymous’ principal theoretical mechanism of behavior change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(3):454-463.

4. Zemore SE. A role for spiritual change in the benefits of 12-step involvement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(10 suppl):76s-79s.

5. Kendler KS, Liu XQ, Gardner CO, et al. Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496-503.

6. Koenig HG, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

7. Carter TM. The effects of spiritual practices on recovery from substance abuse. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1998; 5(5):409-413.

8. Conner BT, Anglin MD, Annon J, et al. Effect of religiosity and spirituality on drug treatment outcomes. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(2):189-198.

9. Robinson EA, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, et al. Six-month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(4):660-668.

10. Heinz AJ, Disney ER, Epstein DH, et al. A focus-group study on spirituality and substance-user treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(1-2):134-153.

11. Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(7):578-583.

12. Pargament KI, Lomax JW. Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):26-32.

13. Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78-85.

14. Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality: 1999. http://www.primarycarecore.org/PDF/137.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

15. Johnstone B, Yoon DP, Franklin KL, et al. Re-conceptualizing the factor structure of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality. J Relig Health. 2009;48(2):146-163.

16. Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, et al. Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):257-264.

17. Pargament K, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2(1):51-76.

18. Afterdeployment.org. Spirituality assessment. http://www.afterdeployment.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/assessment-tools/spirituality-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2014.

19. Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90-96.

20. Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: a new Instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):499-503.

21. Plante TG. Integrating spirituality and psychotherapy: ethical issues and principles to consider. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(9):891-902.

22. Delaney HD, Forcehimes AA, Campbell WP, et al. Integrating spirituality into alcohol treatment. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(2):185-198.

23. Shafranske EP. Religious involvement and professional practices of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30(8):525-532.

24. Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, et al. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):629-634.

25. Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, et al. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(9):1193-1198.

26. Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL, et al. Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: a multiple mediator analysis. Addiction. 2012;107(2):289-299.

27. Nowinski J. Self-help groups for addictions. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, eds. Addictions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999:328-346.

28. SMART recovery: self-management and recovery training. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed January 9, 2014.

29. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. The AA member—medication & other drugs. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 2011.