User login

When his hospital’s board of trustees was considering a palliative-care program seven years ago, hospitalist Stephen Bekanich, MD, wasn’t sure what to expect. What he did know was that his hospitalist group could provide the University of Utah Health System in Salt Lake City answers to staffing and financial issues surrounding the addition of a palliative-care service.

“They looked around and decided the hospitalist group would be the best place to house [the service], based on our experience with a range of medical management issues and the fact that we’re around 24 hours, seven days a week,” says Dr. Bekanich, who in 2006 became the first medical director of the palliative-care service at University of Utah Hospital.

The hospital board eventually selected palliative care as one of its annual projects, Dr. Bekanich says, not just because it was the right thing to do, but also because palliative care increasingly is used as a quality marker for hospitals. Dr. Bekanich says he took the assignment because it provides a nice buffer and change of pace from the stress of full-time HM service. Several colleagues joined him in rotating through palliative care coverage, although he continued to carry a pager most days and nights to support the physicians, advanced practice nurses, social worker, and chaplain with challenging cases.

After six months of operation, Dr. Bekanich went before his hospital board to discuss the program. He presented hospital data that showed the service had helped save the hospital $600,000, along with “thank-you letters” from grateful families and mentions in obituaries.

—Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, director, Univ, of California at San Francisco palliative care service, SHM past president

“A couple of months later, I realized that we needed another nurse practitioner to staff the growing caseload,” he explains. “I went to the chief medical officer and he said to me, ‘I don’t need to see the numbers. I know you’re doing a great job. Just tell me what you need.’ ”

Widely extolled for relieving the physical suffering and emotional distress of seriously ill patients, palliative care has seen rapid advancement in recent years, not only as a humanitarian impulse, but also as a legitimate and recognized medical subspecialty and career choice. Palliative care has its own board certification, fellowships, and training opportunities. For working hospitalists, this subspecialty can complement a career path and enhance job satisfaction. For HM groups, it represents diversification and an additional, albeit modest, income stream, as well as opportunities to improve the quality of hospital care.

“Palliative medicine is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties [ABMS] and nine of its medical specialty boards, which is very significant,” says Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, medical director of UCSF’s palliative-care service. “Along with that come fellowships.”

The Basics

Palliative care’s focus is managing patients’ symptoms, maximizing quality of life, and clarifying treatment goals—regardless of diagnosis or other treatments they might be receiving. It is not hospice care, which is defined by Medicare as treatment for patients with a terminal prognosis of six months or less (see “Hospice and Palliative: End-of-Life Care Siblings,” p. 21). Palliative care and hospice care utilize many of the same techniques, and are combined in the ABMS program for certifying subspecialist physicians.

The interdisciplinary consultation service, where a palliative care consultant rounds with a team that might include physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and chaplains, is the most common palliative-care model in the hospital setting, but other approaches include dedicated units and community-based programs.

The latest data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) count 1,486 operational palliative-care programs in U.S. acute-care hospitals, more than twice as many as a decade before.1 Currently, the demand for physicians certified in hospice and palliative medicine outstrips the supply, which poses challenges to those trying to hire as well as bona fide opportunities for qualified physicians hoping to pursue their dream jobs in the field, says Dr. Pantilat, a past president of SHM.

“A few years ago, it was cutting-edge for hospitals to just have a palliative care program,” Dr. Pantilat says, “but now the focus is on quality and the qualifications of the palliative care physicians and other professionals. Expectations for what palliative care will deliver will only go up.”

UCSF’s palliative care service “lives” within its HM division. Five of the six palliative care attending physicians are hospitalists. They divide weeklong assignments on the service into seven-day commitments at the hospital; each shift includes an on-call pager for night coverage.

A palliative-care shift can be just as emotionally demanding as an HM shift, although usually with fewer patients. One big difference: More time is needed for each palliative care consult, Dr. Pantilat says. A typical consult consists of an intense conversation with the patient and family to explore the patient’s prognosis, family values, and goals for treatment and pain relief.

Additionally, palliative care physicians routinely discuss the psychosocial and spiritual distress that the patient and family normally encounter.

Know When to Call for Help

Hospitalist involvement in palliative care varies by service, individual experience, and institution guidelines. Generally, though, it starts with an understanding of what the service provides and determining when is the right time to call a palliative-care consultant for help (see “Your Page Is Welcomed,” p. 22).

Hospitalists can obtain basic training and incorporate palliative-care principles and practices into the care of all hospitalized patients (see “Training Opportunities,” p. 22). If your hospital has a palliative-care service, hospitalists could join an advisory committee or provide backup coverage. If no such service exists, hospitalists could advocate with other physicians and hospital administrators to start one, Dr. Pantilat says.

Some hospitalists go deeper, developing subspecialty expertise and board certification in palliative medicine.

For HM groups, integration with a palliative-care service could mean taking on medical management of the service. If your group chooses to go this route, experts suggest you research how busy the service could be and gauge the interest of physicians in your group. Also check on the willingness of hospitalists in the group who are not interested in working on the palliative care service; they could help free up time for those who want to do it.

What Every Hospitalist Should Know

The basic clinical skills needed to perform palliative medicine include:

- Titrating opioid analgesics;

- Using adjuvant pain medications;

- Managing nonpain-related symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspnea, seizures, and anorexia;

- Managing delirium, anxiety, and depression;

- Communicating sensitive information;

- Working with cultural issues and differences; and

- Bereavement support for families.

“Every hospitalist should know how to elicit a patient’s goals of care and incorporate them into routine treatment, be fluid and comfortable discussing advance-care planning, and possess basic skills in pain management,” says Jeanie Youngwerth, MD, hospitalist and director of the palliative-care service at the University of Colorado Denver. “Unfortunately, we’re not there yet as a field, given current residency training in internal medicine. Our center has a hospitalist residency training track, and those residents all get dedicated, palliative care experience.”

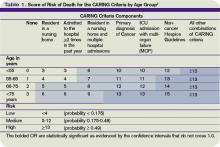

Knowing when to refer a patient to a palliative-care specialist is another important skill, Dr. Youngwerth explains. The CARING criteria, developed by Dr. Youngwerth’s colleagues at UC Denver, are a simple set of prognostic markers that identify patients with limited life expectancy at the time of hospital admission. The CARING criteria are a set of prognostic criteria that incorporate cancer diagnosis, repeated hospital admissions, ICU stays with multi-organ failure, residence in a nursing home, and meeting non-cancer hospice guidelines developed by the National Hospice Organization, which collectively correlate with the need for a palliative-care consultation (see Table 1, above).2

A simpler way to initially assess a patient’s need for palliative care is to ask yourself: Would you be surprised if you found out this patient had died within a year? “If physicians don’t think the patient is going to be alive in a year, then they should incorporate palliative care into the care plan,” Dr. Youngwerth says. “The next question is: Should I do it myself, or refer for a palliative-care consultation?”

Dr. Bekanich, who starting this month will head a new palliative care program at the University of Miami that features a 10-bed inpatient unit, encourages hospitalists to avoid focusing only on terminally ill patients when considering a palliative consult. Any seriously ill patient with unmet needs could benefit from a referral, he says.

“Lots of hospitalists are good at controlling nausea and vomiting, but if the symptoms are refractory or have uncommon presentations, I would like to get on board as the palliative care consultant,” Dr. Bekanich says. “I have also tried to emphasize to my group the importance of timely family meetings.

“If they don’t have the time or the skills, or if they expect a difficult meeting, for example, due to religious or cultural differences, send these patients our way. And when there are ethical issues that need to be addressed, or a particular need for educating patients and families about the disease process and what to expect, I like consultations like that.”

Bad Business or New Revenue Stream?

The traditional business model for palliative-care services has focused on the potential contributions to the hospital’s bottom line through reduced length of stay and cost avoidance for a group of patients who can be among the hospital’s most challenging and expensive. Palliative care saves time and money by working with patients and their families to clarify their values and treatment preferences, which routinely differ from standard treatment modes.

A recent multisite study of palliative care by Morrison et al found that the use of palliative care services saved from $1,700 to $4,900 per admission in direct costs, compared with similar patients who did not receive palliative care.3 The savings were realized primarily through reduced laboratory, pharmacy, and ICU costs.

Cost avoidance, combined with palliative care’s contributions to quality and patient satisfaction, is essential to the field’s growth. Even though physician consultation visits are billable, a palliative-care service rarely covers its staffing costs solely with billing revenue. A service requires nonbillable support from administration and midlevel providers, including nurses and social workers.

“Integrating palliative care into the work of hospitalists is a great idea,” says Jean Kutner, MD, head of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Colorado Denver. However, there are important issues related to scheduling, availability, and commitment that need to be explored before a group launches a new service. “I’d want to have discussions about how the palliative-care business model fits with our hospital medicine model and an agreement with the hospital on goals and metrics,” she says.

Hospitalists Fill a Need

Whether a full-fledged palliative-care service fits your group’s dynamic or not, hospitalists as a whole should be competent in basic palliative care. Community and rural hospitals need HM to bridge this gap and deliver quality care to seriously ill patients.

“I started at a community hospital, Eden Medical Center in Castro Valley, California. I had a personal interest in palliative care and realized there’s a tremendous need for it in community hospitals,” says Heather A. Harris, MD, a hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital who previously worked with Dr. Pantilat’s palliative care service at UCSF. “We deal with end-of-life issues on a regular basis—whether recognized or not—based on our caseloads and requests for consultations.

“I got a little perspective about palliative care while a resident at UCSF. But as I’ve gotten further into this, I have come to realize that there is an actual skill set that needs to be learned to do it properly.”

Dr. Harris says there is a big difference between physicians helping patients with end-of-life issues the best they can and being part of a “dedicated, interdisciplinary team.”

“Palliative care is a wonderful opportunity for hospitalists,” she says. “It’s already part of your practice. Why not do it in a more organized fashion?” TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance medical writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Palliative care programs continue rapid growth in U.S. hospitals. Center to Advance Palliative Care website. Available at: www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/04-05-10. Accessed July 15, 2010.

- Fischer SM, Gozansky WS, Sauaia A, Min SJ, Kutner JS, Kramer A. A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(4):285-292.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.

When his hospital’s board of trustees was considering a palliative-care program seven years ago, hospitalist Stephen Bekanich, MD, wasn’t sure what to expect. What he did know was that his hospitalist group could provide the University of Utah Health System in Salt Lake City answers to staffing and financial issues surrounding the addition of a palliative-care service.

“They looked around and decided the hospitalist group would be the best place to house [the service], based on our experience with a range of medical management issues and the fact that we’re around 24 hours, seven days a week,” says Dr. Bekanich, who in 2006 became the first medical director of the palliative-care service at University of Utah Hospital.

The hospital board eventually selected palliative care as one of its annual projects, Dr. Bekanich says, not just because it was the right thing to do, but also because palliative care increasingly is used as a quality marker for hospitals. Dr. Bekanich says he took the assignment because it provides a nice buffer and change of pace from the stress of full-time HM service. Several colleagues joined him in rotating through palliative care coverage, although he continued to carry a pager most days and nights to support the physicians, advanced practice nurses, social worker, and chaplain with challenging cases.

After six months of operation, Dr. Bekanich went before his hospital board to discuss the program. He presented hospital data that showed the service had helped save the hospital $600,000, along with “thank-you letters” from grateful families and mentions in obituaries.

—Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, director, Univ, of California at San Francisco palliative care service, SHM past president

“A couple of months later, I realized that we needed another nurse practitioner to staff the growing caseload,” he explains. “I went to the chief medical officer and he said to me, ‘I don’t need to see the numbers. I know you’re doing a great job. Just tell me what you need.’ ”

Widely extolled for relieving the physical suffering and emotional distress of seriously ill patients, palliative care has seen rapid advancement in recent years, not only as a humanitarian impulse, but also as a legitimate and recognized medical subspecialty and career choice. Palliative care has its own board certification, fellowships, and training opportunities. For working hospitalists, this subspecialty can complement a career path and enhance job satisfaction. For HM groups, it represents diversification and an additional, albeit modest, income stream, as well as opportunities to improve the quality of hospital care.

“Palliative medicine is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties [ABMS] and nine of its medical specialty boards, which is very significant,” says Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, medical director of UCSF’s palliative-care service. “Along with that come fellowships.”

The Basics

Palliative care’s focus is managing patients’ symptoms, maximizing quality of life, and clarifying treatment goals—regardless of diagnosis or other treatments they might be receiving. It is not hospice care, which is defined by Medicare as treatment for patients with a terminal prognosis of six months or less (see “Hospice and Palliative: End-of-Life Care Siblings,” p. 21). Palliative care and hospice care utilize many of the same techniques, and are combined in the ABMS program for certifying subspecialist physicians.

The interdisciplinary consultation service, where a palliative care consultant rounds with a team that might include physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and chaplains, is the most common palliative-care model in the hospital setting, but other approaches include dedicated units and community-based programs.

The latest data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) count 1,486 operational palliative-care programs in U.S. acute-care hospitals, more than twice as many as a decade before.1 Currently, the demand for physicians certified in hospice and palliative medicine outstrips the supply, which poses challenges to those trying to hire as well as bona fide opportunities for qualified physicians hoping to pursue their dream jobs in the field, says Dr. Pantilat, a past president of SHM.

“A few years ago, it was cutting-edge for hospitals to just have a palliative care program,” Dr. Pantilat says, “but now the focus is on quality and the qualifications of the palliative care physicians and other professionals. Expectations for what palliative care will deliver will only go up.”

UCSF’s palliative care service “lives” within its HM division. Five of the six palliative care attending physicians are hospitalists. They divide weeklong assignments on the service into seven-day commitments at the hospital; each shift includes an on-call pager for night coverage.

A palliative-care shift can be just as emotionally demanding as an HM shift, although usually with fewer patients. One big difference: More time is needed for each palliative care consult, Dr. Pantilat says. A typical consult consists of an intense conversation with the patient and family to explore the patient’s prognosis, family values, and goals for treatment and pain relief.

Additionally, palliative care physicians routinely discuss the psychosocial and spiritual distress that the patient and family normally encounter.

Know When to Call for Help

Hospitalist involvement in palliative care varies by service, individual experience, and institution guidelines. Generally, though, it starts with an understanding of what the service provides and determining when is the right time to call a palliative-care consultant for help (see “Your Page Is Welcomed,” p. 22).

Hospitalists can obtain basic training and incorporate palliative-care principles and practices into the care of all hospitalized patients (see “Training Opportunities,” p. 22). If your hospital has a palliative-care service, hospitalists could join an advisory committee or provide backup coverage. If no such service exists, hospitalists could advocate with other physicians and hospital administrators to start one, Dr. Pantilat says.

Some hospitalists go deeper, developing subspecialty expertise and board certification in palliative medicine.

For HM groups, integration with a palliative-care service could mean taking on medical management of the service. If your group chooses to go this route, experts suggest you research how busy the service could be and gauge the interest of physicians in your group. Also check on the willingness of hospitalists in the group who are not interested in working on the palliative care service; they could help free up time for those who want to do it.

What Every Hospitalist Should Know

The basic clinical skills needed to perform palliative medicine include:

- Titrating opioid analgesics;

- Using adjuvant pain medications;

- Managing nonpain-related symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspnea, seizures, and anorexia;

- Managing delirium, anxiety, and depression;

- Communicating sensitive information;

- Working with cultural issues and differences; and

- Bereavement support for families.

“Every hospitalist should know how to elicit a patient’s goals of care and incorporate them into routine treatment, be fluid and comfortable discussing advance-care planning, and possess basic skills in pain management,” says Jeanie Youngwerth, MD, hospitalist and director of the palliative-care service at the University of Colorado Denver. “Unfortunately, we’re not there yet as a field, given current residency training in internal medicine. Our center has a hospitalist residency training track, and those residents all get dedicated, palliative care experience.”

Knowing when to refer a patient to a palliative-care specialist is another important skill, Dr. Youngwerth explains. The CARING criteria, developed by Dr. Youngwerth’s colleagues at UC Denver, are a simple set of prognostic markers that identify patients with limited life expectancy at the time of hospital admission. The CARING criteria are a set of prognostic criteria that incorporate cancer diagnosis, repeated hospital admissions, ICU stays with multi-organ failure, residence in a nursing home, and meeting non-cancer hospice guidelines developed by the National Hospice Organization, which collectively correlate with the need for a palliative-care consultation (see Table 1, above).2

A simpler way to initially assess a patient’s need for palliative care is to ask yourself: Would you be surprised if you found out this patient had died within a year? “If physicians don’t think the patient is going to be alive in a year, then they should incorporate palliative care into the care plan,” Dr. Youngwerth says. “The next question is: Should I do it myself, or refer for a palliative-care consultation?”

Dr. Bekanich, who starting this month will head a new palliative care program at the University of Miami that features a 10-bed inpatient unit, encourages hospitalists to avoid focusing only on terminally ill patients when considering a palliative consult. Any seriously ill patient with unmet needs could benefit from a referral, he says.

“Lots of hospitalists are good at controlling nausea and vomiting, but if the symptoms are refractory or have uncommon presentations, I would like to get on board as the palliative care consultant,” Dr. Bekanich says. “I have also tried to emphasize to my group the importance of timely family meetings.

“If they don’t have the time or the skills, or if they expect a difficult meeting, for example, due to religious or cultural differences, send these patients our way. And when there are ethical issues that need to be addressed, or a particular need for educating patients and families about the disease process and what to expect, I like consultations like that.”

Bad Business or New Revenue Stream?

The traditional business model for palliative-care services has focused on the potential contributions to the hospital’s bottom line through reduced length of stay and cost avoidance for a group of patients who can be among the hospital’s most challenging and expensive. Palliative care saves time and money by working with patients and their families to clarify their values and treatment preferences, which routinely differ from standard treatment modes.

A recent multisite study of palliative care by Morrison et al found that the use of palliative care services saved from $1,700 to $4,900 per admission in direct costs, compared with similar patients who did not receive palliative care.3 The savings were realized primarily through reduced laboratory, pharmacy, and ICU costs.

Cost avoidance, combined with palliative care’s contributions to quality and patient satisfaction, is essential to the field’s growth. Even though physician consultation visits are billable, a palliative-care service rarely covers its staffing costs solely with billing revenue. A service requires nonbillable support from administration and midlevel providers, including nurses and social workers.

“Integrating palliative care into the work of hospitalists is a great idea,” says Jean Kutner, MD, head of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Colorado Denver. However, there are important issues related to scheduling, availability, and commitment that need to be explored before a group launches a new service. “I’d want to have discussions about how the palliative-care business model fits with our hospital medicine model and an agreement with the hospital on goals and metrics,” she says.

Hospitalists Fill a Need

Whether a full-fledged palliative-care service fits your group’s dynamic or not, hospitalists as a whole should be competent in basic palliative care. Community and rural hospitals need HM to bridge this gap and deliver quality care to seriously ill patients.

“I started at a community hospital, Eden Medical Center in Castro Valley, California. I had a personal interest in palliative care and realized there’s a tremendous need for it in community hospitals,” says Heather A. Harris, MD, a hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital who previously worked with Dr. Pantilat’s palliative care service at UCSF. “We deal with end-of-life issues on a regular basis—whether recognized or not—based on our caseloads and requests for consultations.

“I got a little perspective about palliative care while a resident at UCSF. But as I’ve gotten further into this, I have come to realize that there is an actual skill set that needs to be learned to do it properly.”

Dr. Harris says there is a big difference between physicians helping patients with end-of-life issues the best they can and being part of a “dedicated, interdisciplinary team.”

“Palliative care is a wonderful opportunity for hospitalists,” she says. “It’s already part of your practice. Why not do it in a more organized fashion?” TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance medical writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Palliative care programs continue rapid growth in U.S. hospitals. Center to Advance Palliative Care website. Available at: www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/04-05-10. Accessed July 15, 2010.

- Fischer SM, Gozansky WS, Sauaia A, Min SJ, Kutner JS, Kramer A. A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(4):285-292.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.

When his hospital’s board of trustees was considering a palliative-care program seven years ago, hospitalist Stephen Bekanich, MD, wasn’t sure what to expect. What he did know was that his hospitalist group could provide the University of Utah Health System in Salt Lake City answers to staffing and financial issues surrounding the addition of a palliative-care service.

“They looked around and decided the hospitalist group would be the best place to house [the service], based on our experience with a range of medical management issues and the fact that we’re around 24 hours, seven days a week,” says Dr. Bekanich, who in 2006 became the first medical director of the palliative-care service at University of Utah Hospital.

The hospital board eventually selected palliative care as one of its annual projects, Dr. Bekanich says, not just because it was the right thing to do, but also because palliative care increasingly is used as a quality marker for hospitals. Dr. Bekanich says he took the assignment because it provides a nice buffer and change of pace from the stress of full-time HM service. Several colleagues joined him in rotating through palliative care coverage, although he continued to carry a pager most days and nights to support the physicians, advanced practice nurses, social worker, and chaplain with challenging cases.

After six months of operation, Dr. Bekanich went before his hospital board to discuss the program. He presented hospital data that showed the service had helped save the hospital $600,000, along with “thank-you letters” from grateful families and mentions in obituaries.

—Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, director, Univ, of California at San Francisco palliative care service, SHM past president

“A couple of months later, I realized that we needed another nurse practitioner to staff the growing caseload,” he explains. “I went to the chief medical officer and he said to me, ‘I don’t need to see the numbers. I know you’re doing a great job. Just tell me what you need.’ ”

Widely extolled for relieving the physical suffering and emotional distress of seriously ill patients, palliative care has seen rapid advancement in recent years, not only as a humanitarian impulse, but also as a legitimate and recognized medical subspecialty and career choice. Palliative care has its own board certification, fellowships, and training opportunities. For working hospitalists, this subspecialty can complement a career path and enhance job satisfaction. For HM groups, it represents diversification and an additional, albeit modest, income stream, as well as opportunities to improve the quality of hospital care.

“Palliative medicine is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties [ABMS] and nine of its medical specialty boards, which is very significant,” says Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, medical director of UCSF’s palliative-care service. “Along with that come fellowships.”

The Basics

Palliative care’s focus is managing patients’ symptoms, maximizing quality of life, and clarifying treatment goals—regardless of diagnosis or other treatments they might be receiving. It is not hospice care, which is defined by Medicare as treatment for patients with a terminal prognosis of six months or less (see “Hospice and Palliative: End-of-Life Care Siblings,” p. 21). Palliative care and hospice care utilize many of the same techniques, and are combined in the ABMS program for certifying subspecialist physicians.

The interdisciplinary consultation service, where a palliative care consultant rounds with a team that might include physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and chaplains, is the most common palliative-care model in the hospital setting, but other approaches include dedicated units and community-based programs.

The latest data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) count 1,486 operational palliative-care programs in U.S. acute-care hospitals, more than twice as many as a decade before.1 Currently, the demand for physicians certified in hospice and palliative medicine outstrips the supply, which poses challenges to those trying to hire as well as bona fide opportunities for qualified physicians hoping to pursue their dream jobs in the field, says Dr. Pantilat, a past president of SHM.

“A few years ago, it was cutting-edge for hospitals to just have a palliative care program,” Dr. Pantilat says, “but now the focus is on quality and the qualifications of the palliative care physicians and other professionals. Expectations for what palliative care will deliver will only go up.”

UCSF’s palliative care service “lives” within its HM division. Five of the six palliative care attending physicians are hospitalists. They divide weeklong assignments on the service into seven-day commitments at the hospital; each shift includes an on-call pager for night coverage.

A palliative-care shift can be just as emotionally demanding as an HM shift, although usually with fewer patients. One big difference: More time is needed for each palliative care consult, Dr. Pantilat says. A typical consult consists of an intense conversation with the patient and family to explore the patient’s prognosis, family values, and goals for treatment and pain relief.

Additionally, palliative care physicians routinely discuss the psychosocial and spiritual distress that the patient and family normally encounter.

Know When to Call for Help

Hospitalist involvement in palliative care varies by service, individual experience, and institution guidelines. Generally, though, it starts with an understanding of what the service provides and determining when is the right time to call a palliative-care consultant for help (see “Your Page Is Welcomed,” p. 22).

Hospitalists can obtain basic training and incorporate palliative-care principles and practices into the care of all hospitalized patients (see “Training Opportunities,” p. 22). If your hospital has a palliative-care service, hospitalists could join an advisory committee or provide backup coverage. If no such service exists, hospitalists could advocate with other physicians and hospital administrators to start one, Dr. Pantilat says.

Some hospitalists go deeper, developing subspecialty expertise and board certification in palliative medicine.

For HM groups, integration with a palliative-care service could mean taking on medical management of the service. If your group chooses to go this route, experts suggest you research how busy the service could be and gauge the interest of physicians in your group. Also check on the willingness of hospitalists in the group who are not interested in working on the palliative care service; they could help free up time for those who want to do it.

What Every Hospitalist Should Know

The basic clinical skills needed to perform palliative medicine include:

- Titrating opioid analgesics;

- Using adjuvant pain medications;

- Managing nonpain-related symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspnea, seizures, and anorexia;

- Managing delirium, anxiety, and depression;

- Communicating sensitive information;

- Working with cultural issues and differences; and

- Bereavement support for families.

“Every hospitalist should know how to elicit a patient’s goals of care and incorporate them into routine treatment, be fluid and comfortable discussing advance-care planning, and possess basic skills in pain management,” says Jeanie Youngwerth, MD, hospitalist and director of the palliative-care service at the University of Colorado Denver. “Unfortunately, we’re not there yet as a field, given current residency training in internal medicine. Our center has a hospitalist residency training track, and those residents all get dedicated, palliative care experience.”

Knowing when to refer a patient to a palliative-care specialist is another important skill, Dr. Youngwerth explains. The CARING criteria, developed by Dr. Youngwerth’s colleagues at UC Denver, are a simple set of prognostic markers that identify patients with limited life expectancy at the time of hospital admission. The CARING criteria are a set of prognostic criteria that incorporate cancer diagnosis, repeated hospital admissions, ICU stays with multi-organ failure, residence in a nursing home, and meeting non-cancer hospice guidelines developed by the National Hospice Organization, which collectively correlate with the need for a palliative-care consultation (see Table 1, above).2

A simpler way to initially assess a patient’s need for palliative care is to ask yourself: Would you be surprised if you found out this patient had died within a year? “If physicians don’t think the patient is going to be alive in a year, then they should incorporate palliative care into the care plan,” Dr. Youngwerth says. “The next question is: Should I do it myself, or refer for a palliative-care consultation?”

Dr. Bekanich, who starting this month will head a new palliative care program at the University of Miami that features a 10-bed inpatient unit, encourages hospitalists to avoid focusing only on terminally ill patients when considering a palliative consult. Any seriously ill patient with unmet needs could benefit from a referral, he says.

“Lots of hospitalists are good at controlling nausea and vomiting, but if the symptoms are refractory or have uncommon presentations, I would like to get on board as the palliative care consultant,” Dr. Bekanich says. “I have also tried to emphasize to my group the importance of timely family meetings.

“If they don’t have the time or the skills, or if they expect a difficult meeting, for example, due to religious or cultural differences, send these patients our way. And when there are ethical issues that need to be addressed, or a particular need for educating patients and families about the disease process and what to expect, I like consultations like that.”

Bad Business or New Revenue Stream?

The traditional business model for palliative-care services has focused on the potential contributions to the hospital’s bottom line through reduced length of stay and cost avoidance for a group of patients who can be among the hospital’s most challenging and expensive. Palliative care saves time and money by working with patients and their families to clarify their values and treatment preferences, which routinely differ from standard treatment modes.

A recent multisite study of palliative care by Morrison et al found that the use of palliative care services saved from $1,700 to $4,900 per admission in direct costs, compared with similar patients who did not receive palliative care.3 The savings were realized primarily through reduced laboratory, pharmacy, and ICU costs.

Cost avoidance, combined with palliative care’s contributions to quality and patient satisfaction, is essential to the field’s growth. Even though physician consultation visits are billable, a palliative-care service rarely covers its staffing costs solely with billing revenue. A service requires nonbillable support from administration and midlevel providers, including nurses and social workers.

“Integrating palliative care into the work of hospitalists is a great idea,” says Jean Kutner, MD, head of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Colorado Denver. However, there are important issues related to scheduling, availability, and commitment that need to be explored before a group launches a new service. “I’d want to have discussions about how the palliative-care business model fits with our hospital medicine model and an agreement with the hospital on goals and metrics,” she says.

Hospitalists Fill a Need

Whether a full-fledged palliative-care service fits your group’s dynamic or not, hospitalists as a whole should be competent in basic palliative care. Community and rural hospitals need HM to bridge this gap and deliver quality care to seriously ill patients.

“I started at a community hospital, Eden Medical Center in Castro Valley, California. I had a personal interest in palliative care and realized there’s a tremendous need for it in community hospitals,” says Heather A. Harris, MD, a hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital who previously worked with Dr. Pantilat’s palliative care service at UCSF. “We deal with end-of-life issues on a regular basis—whether recognized or not—based on our caseloads and requests for consultations.

“I got a little perspective about palliative care while a resident at UCSF. But as I’ve gotten further into this, I have come to realize that there is an actual skill set that needs to be learned to do it properly.”

Dr. Harris says there is a big difference between physicians helping patients with end-of-life issues the best they can and being part of a “dedicated, interdisciplinary team.”

“Palliative care is a wonderful opportunity for hospitalists,” she says. “It’s already part of your practice. Why not do it in a more organized fashion?” TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance medical writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Palliative care programs continue rapid growth in U.S. hospitals. Center to Advance Palliative Care website. Available at: www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/04-05-10. Accessed July 15, 2010.

- Fischer SM, Gozansky WS, Sauaia A, Min SJ, Kutner JS, Kramer A. A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(4):285-292.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.