User login

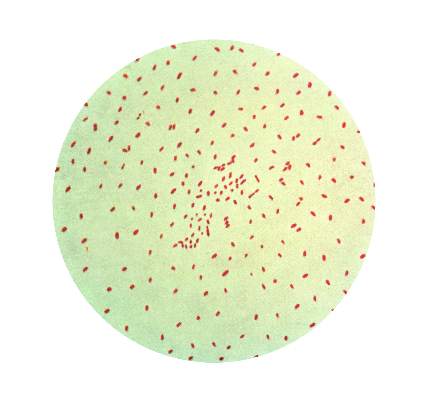

Asymptomatic transmission may help explain the recent rise in incidence of Bordetella pertussis, according to a new study.

Both the United States and the United Kingdom have witnessed increased rates of whooping cough diagnosis, despite high vaccination for B. pertussis. “It may be that aP [acellular pertussis]–vaccinated infected people are less efficient at transmitting B. pertussis, compared with unvaccinated infected people, though it is not clear to what extent,” said Dr. Benjamin M. Althouse and Dr. Samuel V. Scarpino of the Santa Fe (N.M.) Institute (BMC Medicine 2015 [doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0382-8]). “The results on vaccination have important public health and clinical implications, especially related to recommendations for isolating unvaccinated or partially vaccinated infants.”

The researchers analyzed reported cases and incidence of B. pertussis from the United States and United Kingdom with data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1922-2012) and Public Health England (1940-2013), respectively.

Using 36 U.S. B. pertussis isolates from 1935 to 2005, the researchers created a phylodynamic model and used a mathematical model to apply the data to understand the public health and clinical impact of asymptomatic transmission.

Utilizing a wavelet analysis, the incidence of B. pertussis in the United Kingdom returned to a 4-year cyclic pattern similar to the prevaccine era after switching to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine. Both countries demonstrated age-specific attack rate changes after switching from the whole-cell to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino noted these observations may be a result of asymptomatic transmission in acellular-vaccinated individuals and cannot be fully explained by B. pertussis evolution or waning immunity.

Finally, as the percentage of acellular vaccination increases, the number of asymptomatic cases of B. pertussis increases. Vaccination levels in the low to moderate range were associated with a 5- to 15-fold increase in symptomatic cases, whereas very high levels (greater than 99%) of vaccination demonstrated no change in the rate of symptomatic cases. The researchers suggest the results are consistent with the increased B. pertussis incidence in 2012 that was 5.4-folder higher than in 1985-1995.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino concluded that the models demonstrate that an acellular B. pertussis vaccination that does not prevent transmission in asymptomatic individuals could account for the increased incidence and failure of unvaccinated infant cocooning.

The research was supported by the Omidyar Group and the Santa Fe Institute. The researchers report no competing interests.

Asymptomatic transmission may help explain the recent rise in incidence of Bordetella pertussis, according to a new study.

Both the United States and the United Kingdom have witnessed increased rates of whooping cough diagnosis, despite high vaccination for B. pertussis. “It may be that aP [acellular pertussis]–vaccinated infected people are less efficient at transmitting B. pertussis, compared with unvaccinated infected people, though it is not clear to what extent,” said Dr. Benjamin M. Althouse and Dr. Samuel V. Scarpino of the Santa Fe (N.M.) Institute (BMC Medicine 2015 [doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0382-8]). “The results on vaccination have important public health and clinical implications, especially related to recommendations for isolating unvaccinated or partially vaccinated infants.”

The researchers analyzed reported cases and incidence of B. pertussis from the United States and United Kingdom with data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1922-2012) and Public Health England (1940-2013), respectively.

Using 36 U.S. B. pertussis isolates from 1935 to 2005, the researchers created a phylodynamic model and used a mathematical model to apply the data to understand the public health and clinical impact of asymptomatic transmission.

Utilizing a wavelet analysis, the incidence of B. pertussis in the United Kingdom returned to a 4-year cyclic pattern similar to the prevaccine era after switching to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine. Both countries demonstrated age-specific attack rate changes after switching from the whole-cell to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino noted these observations may be a result of asymptomatic transmission in acellular-vaccinated individuals and cannot be fully explained by B. pertussis evolution or waning immunity.

Finally, as the percentage of acellular vaccination increases, the number of asymptomatic cases of B. pertussis increases. Vaccination levels in the low to moderate range were associated with a 5- to 15-fold increase in symptomatic cases, whereas very high levels (greater than 99%) of vaccination demonstrated no change in the rate of symptomatic cases. The researchers suggest the results are consistent with the increased B. pertussis incidence in 2012 that was 5.4-folder higher than in 1985-1995.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino concluded that the models demonstrate that an acellular B. pertussis vaccination that does not prevent transmission in asymptomatic individuals could account for the increased incidence and failure of unvaccinated infant cocooning.

The research was supported by the Omidyar Group and the Santa Fe Institute. The researchers report no competing interests.

Asymptomatic transmission may help explain the recent rise in incidence of Bordetella pertussis, according to a new study.

Both the United States and the United Kingdom have witnessed increased rates of whooping cough diagnosis, despite high vaccination for B. pertussis. “It may be that aP [acellular pertussis]–vaccinated infected people are less efficient at transmitting B. pertussis, compared with unvaccinated infected people, though it is not clear to what extent,” said Dr. Benjamin M. Althouse and Dr. Samuel V. Scarpino of the Santa Fe (N.M.) Institute (BMC Medicine 2015 [doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0382-8]). “The results on vaccination have important public health and clinical implications, especially related to recommendations for isolating unvaccinated or partially vaccinated infants.”

The researchers analyzed reported cases and incidence of B. pertussis from the United States and United Kingdom with data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1922-2012) and Public Health England (1940-2013), respectively.

Using 36 U.S. B. pertussis isolates from 1935 to 2005, the researchers created a phylodynamic model and used a mathematical model to apply the data to understand the public health and clinical impact of asymptomatic transmission.

Utilizing a wavelet analysis, the incidence of B. pertussis in the United Kingdom returned to a 4-year cyclic pattern similar to the prevaccine era after switching to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine. Both countries demonstrated age-specific attack rate changes after switching from the whole-cell to the acellular B. pertussis vaccine.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino noted these observations may be a result of asymptomatic transmission in acellular-vaccinated individuals and cannot be fully explained by B. pertussis evolution or waning immunity.

Finally, as the percentage of acellular vaccination increases, the number of asymptomatic cases of B. pertussis increases. Vaccination levels in the low to moderate range were associated with a 5- to 15-fold increase in symptomatic cases, whereas very high levels (greater than 99%) of vaccination demonstrated no change in the rate of symptomatic cases. The researchers suggest the results are consistent with the increased B. pertussis incidence in 2012 that was 5.4-folder higher than in 1985-1995.

Dr. Althouse and Dr. Scarpino concluded that the models demonstrate that an acellular B. pertussis vaccination that does not prevent transmission in asymptomatic individuals could account for the increased incidence and failure of unvaccinated infant cocooning.

The research was supported by the Omidyar Group and the Santa Fe Institute. The researchers report no competing interests.

FROM BMC MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Asymptomatic transmission of B. pertussis by vaccinated individuals may explain rise in whooping cough.

Major finding: Phylodynamic and wavelet analyses of data are consistent with asymptomatic transmission of B. pertussis.

Data source: Data of reported cases of B. pertussis was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Public Health England and analysis of 36 U.S. isolates from 1935 to 2005.

Disclosures: The researchers report no competing interests and were supported by the Omidyar Group and the Santa Fe Institute.