User login

How often does someone ask you for help in getting an appointment with a psychiatrist? With the “double expansion” in access to mental health care – because of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – many more people are seeking help for mental health and substance use problems. But without more practitioners being produced, the waiting lists are getting longer.

A recent study found that 40% (146 of 360) of psychiatrists listed on insurance plans in three states could not be reached. Of the 214 who were reachable, 43% were unavailable, either because the psychiatrists were not accepting new patients or because they did not treat adult outpatients (e.g., inpatient only). Of the 123 psychiatrists left, the callers were able to schedule appointments with 93 (76%) of them. These results are similar to a 2007 study, where 44% of mental health professionals from seven health plans were unreachable.

Problems with access to psychiatric care is not a new problem. Mental health carve-outs are used by managed care organizations (MCOs) to manage the mental health benefits, but create inefficiency in claims management and clinical care coordination. While this model seems to be losing popularity, these managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) often do not integrate well with the MCO, may not share the same standards for network adequacy, and often have different provider directories from those of the MCO, making it more complex for patients to access providers.

While the Parity Act has somewhat improved the problem of rate disparities, the historically low rates paid to psychiatrists by MBHOs have led to high levels of insurance nonparticipation, as much as 50%. Compounding this problem is the fact that plan members often find it hard to access those practitioners who do participate with their insurance.

The Maryland Psychological Association conducted in 2007 with Open Minds a “secret shopper” survey of more than 900 behavioral health providers from seven different online carrier directories in Maryland. Their goal was to assess the extent to which problems with access to care were related to inadequate insurance provider directories.

They found that 44% of the listed providers were unreachable based on the contact information in the directories, and only a small proportion was actually able to see the new “patient” in an appropriate time frame. The average wait time for a psychiatrist was 20 days, for a psychologist was 15 days, and for other mental health professionals was 11 days.

The study, published (Psychiatric Serv. 2014 Oct. 15 [doi:10.1176/appi.ps.2014000051]), illustrates how hard it can be to get an appointment with a psychiatrist, regardless of who the payer is. The authors called 360 psychiatrists who were listed in the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) online directories in Boston, Chicago, and Houston. Callers posed as people with depressive symptoms seeking initial appointments. In each city, a third of the psychiatrists received a call from a caller saying they were either Medicare, BCBS, or self-pay. Voicemails were left when possible that included the type of payer. Callers followed up for a second round of calls if they did not hear back.

“Obtaining an outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist was difficult in the three cities we surveyed, and the appointments given were an average of 1 month away,” the authors wrote. Between 20%-27% of the phone numbers in the insurance company directories were wrong numbers, which led, instead, to places like McDonald’s and retail stores. In fact, they were able to reach only one-third of the psychiatrists.

The ACA requires Health Insurance Exchanges to have network provider directories that distinguish those providers who are currently accepting new outpatients. Unfortunately, the act left it up to the states to define network adequacy. For example, in Maryland, the definition of what constitutes an adequate network is left to each qualified health plan to define.

The problem with the health plans’ provider directories is that they are inaccurate, making it look like they have more available providers than they actually do. The plans have no incentive to expose the inadequacy of their network directories, while the regulators lack the staff to police them sufficiently. Meanwhile, provider groups benefit from being included on more lists, and plan members fail to effectively complain to the plans, employers, and regulators.

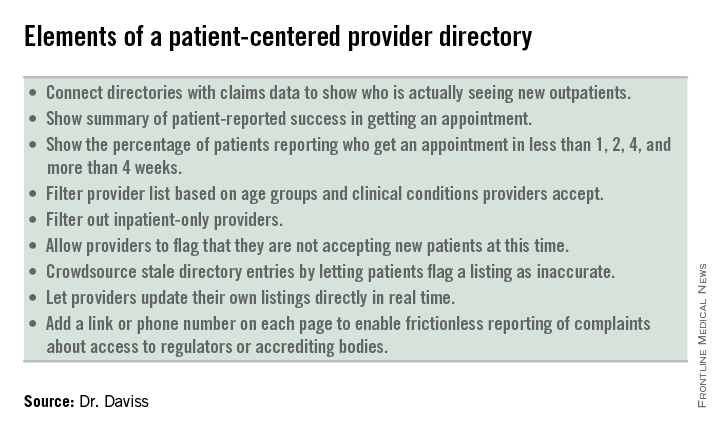

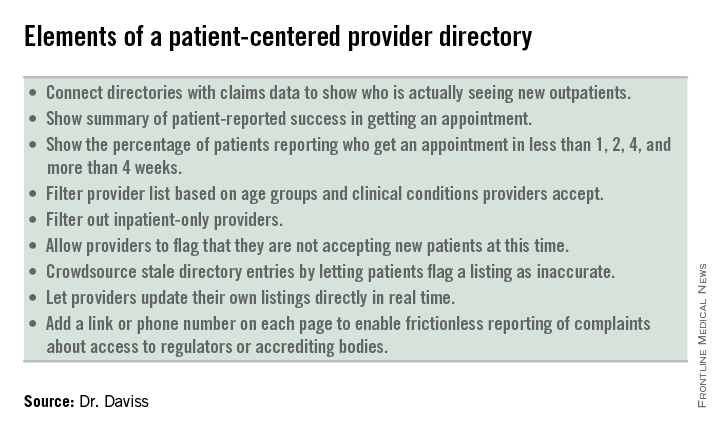

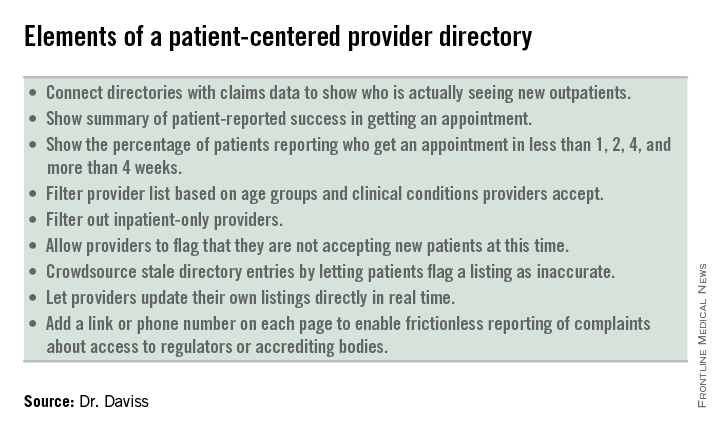

What the industry needs is to move away from these misleading, payer-centered provider directories and move toward transparent, patient-centered provider directories that include elements of crowdsourcing, provider control, and frictionless reporting. Making these changes will give consumers, employers, and regulators more information on provider availability, wait times, and true access to care.

Dr. Daviss is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, cochair of the CCHIT Behavioral Health Work Group, and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. He is found on Twitter @HITshrink, at [email protected], and on the Shrink Rap blog.

How often does someone ask you for help in getting an appointment with a psychiatrist? With the “double expansion” in access to mental health care – because of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – many more people are seeking help for mental health and substance use problems. But without more practitioners being produced, the waiting lists are getting longer.

A recent study found that 40% (146 of 360) of psychiatrists listed on insurance plans in three states could not be reached. Of the 214 who were reachable, 43% were unavailable, either because the psychiatrists were not accepting new patients or because they did not treat adult outpatients (e.g., inpatient only). Of the 123 psychiatrists left, the callers were able to schedule appointments with 93 (76%) of them. These results are similar to a 2007 study, where 44% of mental health professionals from seven health plans were unreachable.

Problems with access to psychiatric care is not a new problem. Mental health carve-outs are used by managed care organizations (MCOs) to manage the mental health benefits, but create inefficiency in claims management and clinical care coordination. While this model seems to be losing popularity, these managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) often do not integrate well with the MCO, may not share the same standards for network adequacy, and often have different provider directories from those of the MCO, making it more complex for patients to access providers.

While the Parity Act has somewhat improved the problem of rate disparities, the historically low rates paid to psychiatrists by MBHOs have led to high levels of insurance nonparticipation, as much as 50%. Compounding this problem is the fact that plan members often find it hard to access those practitioners who do participate with their insurance.

The Maryland Psychological Association conducted in 2007 with Open Minds a “secret shopper” survey of more than 900 behavioral health providers from seven different online carrier directories in Maryland. Their goal was to assess the extent to which problems with access to care were related to inadequate insurance provider directories.

They found that 44% of the listed providers were unreachable based on the contact information in the directories, and only a small proportion was actually able to see the new “patient” in an appropriate time frame. The average wait time for a psychiatrist was 20 days, for a psychologist was 15 days, and for other mental health professionals was 11 days.

The study, published (Psychiatric Serv. 2014 Oct. 15 [doi:10.1176/appi.ps.2014000051]), illustrates how hard it can be to get an appointment with a psychiatrist, regardless of who the payer is. The authors called 360 psychiatrists who were listed in the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) online directories in Boston, Chicago, and Houston. Callers posed as people with depressive symptoms seeking initial appointments. In each city, a third of the psychiatrists received a call from a caller saying they were either Medicare, BCBS, or self-pay. Voicemails were left when possible that included the type of payer. Callers followed up for a second round of calls if they did not hear back.

“Obtaining an outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist was difficult in the three cities we surveyed, and the appointments given were an average of 1 month away,” the authors wrote. Between 20%-27% of the phone numbers in the insurance company directories were wrong numbers, which led, instead, to places like McDonald’s and retail stores. In fact, they were able to reach only one-third of the psychiatrists.

The ACA requires Health Insurance Exchanges to have network provider directories that distinguish those providers who are currently accepting new outpatients. Unfortunately, the act left it up to the states to define network adequacy. For example, in Maryland, the definition of what constitutes an adequate network is left to each qualified health plan to define.

The problem with the health plans’ provider directories is that they are inaccurate, making it look like they have more available providers than they actually do. The plans have no incentive to expose the inadequacy of their network directories, while the regulators lack the staff to police them sufficiently. Meanwhile, provider groups benefit from being included on more lists, and plan members fail to effectively complain to the plans, employers, and regulators.

What the industry needs is to move away from these misleading, payer-centered provider directories and move toward transparent, patient-centered provider directories that include elements of crowdsourcing, provider control, and frictionless reporting. Making these changes will give consumers, employers, and regulators more information on provider availability, wait times, and true access to care.

Dr. Daviss is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, cochair of the CCHIT Behavioral Health Work Group, and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. He is found on Twitter @HITshrink, at [email protected], and on the Shrink Rap blog.

How often does someone ask you for help in getting an appointment with a psychiatrist? With the “double expansion” in access to mental health care – because of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – many more people are seeking help for mental health and substance use problems. But without more practitioners being produced, the waiting lists are getting longer.

A recent study found that 40% (146 of 360) of psychiatrists listed on insurance plans in three states could not be reached. Of the 214 who were reachable, 43% were unavailable, either because the psychiatrists were not accepting new patients or because they did not treat adult outpatients (e.g., inpatient only). Of the 123 psychiatrists left, the callers were able to schedule appointments with 93 (76%) of them. These results are similar to a 2007 study, where 44% of mental health professionals from seven health plans were unreachable.

Problems with access to psychiatric care is not a new problem. Mental health carve-outs are used by managed care organizations (MCOs) to manage the mental health benefits, but create inefficiency in claims management and clinical care coordination. While this model seems to be losing popularity, these managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) often do not integrate well with the MCO, may not share the same standards for network adequacy, and often have different provider directories from those of the MCO, making it more complex for patients to access providers.

While the Parity Act has somewhat improved the problem of rate disparities, the historically low rates paid to psychiatrists by MBHOs have led to high levels of insurance nonparticipation, as much as 50%. Compounding this problem is the fact that plan members often find it hard to access those practitioners who do participate with their insurance.

The Maryland Psychological Association conducted in 2007 with Open Minds a “secret shopper” survey of more than 900 behavioral health providers from seven different online carrier directories in Maryland. Their goal was to assess the extent to which problems with access to care were related to inadequate insurance provider directories.

They found that 44% of the listed providers were unreachable based on the contact information in the directories, and only a small proportion was actually able to see the new “patient” in an appropriate time frame. The average wait time for a psychiatrist was 20 days, for a psychologist was 15 days, and for other mental health professionals was 11 days.

The study, published (Psychiatric Serv. 2014 Oct. 15 [doi:10.1176/appi.ps.2014000051]), illustrates how hard it can be to get an appointment with a psychiatrist, regardless of who the payer is. The authors called 360 psychiatrists who were listed in the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) online directories in Boston, Chicago, and Houston. Callers posed as people with depressive symptoms seeking initial appointments. In each city, a third of the psychiatrists received a call from a caller saying they were either Medicare, BCBS, or self-pay. Voicemails were left when possible that included the type of payer. Callers followed up for a second round of calls if they did not hear back.

“Obtaining an outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist was difficult in the three cities we surveyed, and the appointments given were an average of 1 month away,” the authors wrote. Between 20%-27% of the phone numbers in the insurance company directories were wrong numbers, which led, instead, to places like McDonald’s and retail stores. In fact, they were able to reach only one-third of the psychiatrists.

The ACA requires Health Insurance Exchanges to have network provider directories that distinguish those providers who are currently accepting new outpatients. Unfortunately, the act left it up to the states to define network adequacy. For example, in Maryland, the definition of what constitutes an adequate network is left to each qualified health plan to define.

The problem with the health plans’ provider directories is that they are inaccurate, making it look like they have more available providers than they actually do. The plans have no incentive to expose the inadequacy of their network directories, while the regulators lack the staff to police them sufficiently. Meanwhile, provider groups benefit from being included on more lists, and plan members fail to effectively complain to the plans, employers, and regulators.

What the industry needs is to move away from these misleading, payer-centered provider directories and move toward transparent, patient-centered provider directories that include elements of crowdsourcing, provider control, and frictionless reporting. Making these changes will give consumers, employers, and regulators more information on provider availability, wait times, and true access to care.

Dr. Daviss is chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Washington Medical Center, chair of the APA Committee on Electronic Health Records, cochair of the CCHIT Behavioral Health Work Group, and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, published by Johns Hopkins University Press. He is found on Twitter @HITshrink, at [email protected], and on the Shrink Rap blog.