User login

- A 16-Foley catheter allows the stiffener to pass through with ease; a 30-mL balloon allows for maximum balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid.

- Hold the Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand, then insert the ripener into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix.

- Position a finger on either side of the cervical opening, slide the catheter into the os until it touches the fetal vertex, and inflate the balloon.

- If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on time of induction.

- The Foley balloon is inexpensive and safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.

Postterm pregnancy, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, perceived intrauterine growth restriction or macrosomia, oligohydramnios—these are just a few of many conditions that may call for induction of labor via cervical ripening. Historically, though, this process has been laborious due to the difficult insertion of mechanical agents and the adverse effects of pharmacologic therapies.

When a urologic sound is added as a stiffener to typical Foley balloon catheter insertion, however, cervical ripening becomes a much simpler, straightforward procedure. Here I will describe proper placement techniques and detail this procedure’s benefits over other, more arduous methods.

A brief history

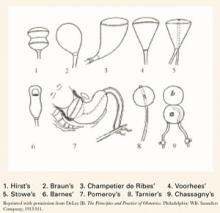

For many years, only mechanical means of ripening were available. In 1851, the intravaginal colpeurynter was used, followed by various intrauterine metreurynters and pear-shaped inflatable rubber bags inserted through the cervix extra-amniotically. Prolonged traction also was used to effect effacement and dilatation. (FIGURE 1)1,2 Later, natural or artificial laminaria or dilataria were implemented.3 But these mechanical methods fell into disfavor due to placement difficulty and concern about infection. Pharmacologic techniques, including vaginal insertion of gels, suppositories, or off-label oral agents, supplanted these earlier methods. However, the complications and side effects—including hyperstimulation (tachysystole, fetal distress, uterine rupture), nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and fever—were troublesome.

Foley catheter. More than 25 years ago, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania instructed its residents in the standard Foleycatheter–insertion ripening technique. During our residencies there, my colleagues and I found this technique to be “cumbersome, somewhat archaic, and aesthetically suboptimal.”4 In 1995, recognizing the need for a safe, simple, effective, inexpensive, and easily reversible method of ripening with minimal side effects, I revisited the Foley balloon catheter—this time using a urologic sound or stiffener to ease insertion. This coupling transformed the awkward visual positioning of the Foley catheter through the endocervical canal into a straightforward tactile placement, similar in ease of accomplishment to the attachment of a scalp electrode to the fetal vertex.

Several reports in the English-language literature on the specifics of Foley ripening have discussed the use of various catheter sizes (14 Foley to 26 Foley) and balloon capacities (25 mL to 50 mL).5-37 In my practice, I use a 16-Foley catheter, which is large enough for the urologic sound to pass through with ease, and a 30-mL balloon, since a larger balloon may burst in the extra-amniotic space.1 Further, 30 mL—three 10-mL vials—of physiologic saline allows for maximum expansion of balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid (TABLE 1). When balloons are inflated beyond 30 mL, expansion is linear along the catheter tubing, forming a cylindrical rather than spherical shape. Increasing the amount of fluid, therefore, provides no increased pressure on the cervix, but rather, displaces the presenting part.

A literature review reveals that investigators for 2 reports utilized nondescript Foley stiffeners or introducers, but ultimately dismissed them as unnecessary. In fact, the researchers concluded that the Foley stiffener could cause membranes to rupture prematurely.31,32 Since 1995, however, this technique has successfully been utilized in at least 113 patients at our institution. With the use of a blunt-tip stylet, we have not seen any rupture of membranes.

FIGURE 1 Various balloon dilators

TABLE 1

Comparison of instilled PSS (in mL) with Foley balloon circumference (in mm)

| PSS | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| CIRCUMFERENCE | 22 | 61 | 99 | 114 | 122 | 131 | 133 | 138 | 141 | 145 |

| PSS=physiologic saline solution | ||||||||||

Technique

Patient preparation. First, counsel the patient and obtain her informed consent. Prior to examination, ensure that a sonogram reading does not show signs of placenta previa; there are no visible lesions or a history of herpes; and gonorrhea, chlamydia, and group B streptococcus (GBS) cultures are negative. If the GBS culture is positive, provide appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy during the ripening and later induction processes. Routinely examine the patient to elicit a Bishop score and confirm fetal vertex presentation.3 Secure a reactive nonstress test prior to Foley insertion.

Preparing the catheter. Using sterile technique, cut the tip from the 16-Foley catheter just beyond the balloon to allow free egress for the stylet. Perform a leak test by filling the balloon with the standard 30 mL of physiologic saline. Withdraw the saline from the balloon and insert the urologic sound into the catheter.

Foley placement. Hold the trimmed Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand. Then insert the fingers into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix. Position a finger at either side of the cervical opening and place the stylet into the os until it touches the fetal vertex (FIGURE 2). If the catheter does not slide in with the stylet, advance the catheter over the stylet into the extra-amniotic space, using the stylet as a rigid splint to assist in the insertion. Maneuver the tip slightly laterally and inflate the balloon partially while simultaneously withdrawing the stylet. By the time the full 30 mL of physiologic saline has been instilled, the stylet should be completely removed.

Testing insertion. Use your fingers to check that the Foley balloon is completely within the extra-amniotic space. A gentle tug will ensure placement above the internal os. Then push the catheter plug into the open end of the Foley and secure the catheter loosely to the patient’s thigh for comfort. Generally, it is unnecessary to place traction on the Foley catheter to effect effacement and dilatation. If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove the catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on the time of induction.

FIGURE 2 Tactile technique of Foley balloon insertion

Advantages

Cost. For disposable, off-the-shelf catheters, current hospital costs are less than $10. The Van Buren Curve Catheter Stylet (C.R. Bard Inc, Bard Urologic Division, Covington, Ga) is $22 and can be reused after sterilization.

Mechanical agents. The simplified catheter technique is certainly easier than the insertion of multiple laminaria. Laminaria tents are said to require no monitoring post insertion since they produce no uterine contractions and initiate gradual cervical dilatation by mechanical swelling and displacement; thus, they may be used for outpatient ripening and are safe in vaginal birth after cesarean attempts. However, they have been associated with increased postpartum and neonatal infections, along with traumatic insertions and vaginal bleeding. In addition, oxytocin is almost always necessary to initiate labor.35 The Foley catheter, on the other hand, does cause uterine contractions, but has been associated with a lower rate of tachysystole (12.7%) when compared with misoprostol (38.4%).16

While the Foley balloon requires intermittent monitoring—and continuous monitoring should labor become active27—it is still safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.36 No common side effects (intrapartum or postpartum fever and vaginal bleeding,12,18,19,24,26 the quite-rare rupture of membranes, along with displacement of the presenting part and umbilical cord prolapse6,21,37) have been seen with this simplified insertion technique.

Pharmacologic agents. Intracervical or intravaginal prostaglandin E2 (dinoprostone) and oral or intravaginal prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) are effective and simple to administer. However, these agents are not readily reversible; require continuous monitoring once administered; and are fraught with adverse effects, including fever, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperstimulation that may lead to tachysystole, uterine rupture, and fetal morbidity and mortality.39-42

Conclusion

Until further controlled studies documenting outpatient safety are available, balloon ripening should be limited to an in-hospital technique, as it causes uterine contractions and even tachysystole.18,4 In the meantime, clinicians should feel confident including this simplified technique in their obstetric armamentarium.

Dr. Freedman reports no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

1. DeLee JB. The Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1913;911-914.

2. Munro Kerr JM, Johnstone RW, Phillips MH (eds). Historical Review of British Obstetrics and Gynecology 1800-1950. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1954;81.-

3. Johnson N. Seaweed and its synthetic analogues in obstetrics and gynecology 450 BC–1990 AD. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:387-389.

4. Trofatter KF. Cervical ripening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;35:476-486.

5. Newton ER. Using mechanical dilators for cervical ripening. Contemp Ob Gyn. December 1987;47-64.

6. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Tovbin J, Arieli S, Caspi E, Bukovsky I. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic catheter balloon: clinical experience and review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:621-627.

7. Poma PA. Cervical ripening: a review and recommendations for clinical practice. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:657-668.

8. Sciscione AC, Pollock M. Preinduction cervical ripening using the Foley catheter. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2000;20(24):1-6.

9. Abramovici D, Goldwasser S, Mabie BC, Mercer BM, Goldwasser R, Sibai BM. A randomized comparison of oral misoprostol versus Foley catheter and oxytocin for induction of labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1108-1112.

10. Atad J, Bornstein J, Calderon I, Petrikovsky BM, Sorokin Y, Abramovici H. Nonpharmaceutical ripening of the unfavorable cervix and induction of labor by a novel double balloon device. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:146-152.

11. Atad J, Hallek M, Ben David Y, Auslander R, Abramovici H. Ripening and dilatation of the unfavorable cervix for induction of labor by a double balloon device: experience with 250 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:29-32.

12. Embrey MP, Mollison BG. The unfavorable cervix and induction using a cervical balloon. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1967;74:44-48.

13. Ezimokhai M, Nwabineli JN. The use of Foley’s catheter in ripening the unfavorable cervix prior to the induction of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:281-286.

14. George SS, Matthews J, Jeyaseelan L, Seshadri L. Cervical ripening induces labor through interleukin 1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;33:285-286.

15. Goldman JB, Wigton TR. A randomized comparison of extra-amniotic saline infusion and intracervical dinoprostone gel for cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

16. Greybush M, Singleton C, Atlas RO, Balducci J, Rust OA. Preinduction cervical ripening techniques compared. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:11-17.

17. Guinn DA, Goepfert AR, Christine M, Owen J, Hauth JC. Extra-amniotic saline, laminaria, or prostaglandin E2 for labor induction with unfavorable cervix: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

18. James C, Peedicayil A, Seshardi L. Use of the Foley catheter as a cervical ripening agent prior to induction of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;47:229-232.

19. Lieberman JR, Piura B, Chaim W, Cohen A. The cervical balloon method for induction of labour. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:499-503.

20. Lurie S, Rabinerson D. Balloon ripening of the cervix [letter]. Lancet. 1997;349:509.-

21. Mahomed K. Foley catheter under traction versus extra-amniotic prostaglandin gel in pre-treatment of the unripe cervix: A randomized, controlled trial. East Afr Med J. 1988;34:98-102.

22. Orhue AAE. Induction of labour at term in primigravidae with low Bishop’s score: a comparison of methods. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;58:119-125.

23. Perry KG, Larmon JE, May WL, Robinette LG, Martin RW. Cervical ripening: a randomized comparison between intravaginal misoprostol and an intracervical balloon catheter combined with intravaginal dinoprostone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1333-1340.

24. Rouben D, Arias F. A randomized trial of extra-amniotic saline infusion plus intracervical Foley catheter balloon versus prostaglandin E2 vaginal gel for ripening the cervix and inducing labor in patients with unfavorable cervixes. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:290-294.

25. Sandhu SK, Tung R. Use of Foley’s catheter to improve the cervical score prior to induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 1984;34:669-672.

26. Schreyer P, Sherman DJ, Ariely S, Herman A, Caspi E. Ripening of the highly unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation or vaginal prostaglandin E2 application. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:938-942.

27. Sciscione AC, McCullough H, Manley JS, Shlossman PA, Pollock M, Colmorgen GHC. A prospective, randomized comparison of Foley catheter insertion versus intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel for preinduction cervical ripening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:55-59.

28. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Pansky M, Caspi E, Bukovsky I, Langer R. Balloon cervical ripening with extra-amniotic infusion of saline or prostaglandin E2: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:375-380.

29. St. Onge RD, Connors GT. Pre-induction cervical ripening: a comparison of intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel versus the Foley catheter. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:687-690.

30. Sullivan CA, Benton LW, Roach H, Smith LG, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Combining medical and mechanical methods of cervical ripening: Does it increase the likelihood of successful induction of labor? J Reprod Med. 1996;41:823-828.

31. Thiery M. Pre-induction cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol Ann. 1983;12:103-146.

32. Thomas IL, Chenoweth JN, Tronc GN, Johnson IR. Preparation for induction of labour of the unfavorable cervix with Foley catheter compared with vaginal prostaglandin. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;26:30-35.

33. Vergalil SR, Guinn DA, Olabi NF, Burd LI, Owen J. A randomized trial of misoprostol and extra-amniotic saline infusion for cervical ripening and labor induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:774-779.

34. Wilson PD. A comparison of four methods of ripening the unfavorable cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978;85:941-944.

35. Witter FR. Cervical ripening for labor induction. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2001;21(3):1-4.

36. Wolff K, Swahn ML, Westgren M. Balloon catheter for induction of labor in nulliparous women with prelabor rupture of the membranes at term: a preliminary report. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:1-4.

37. Yaron Y, Kupfermic MJ, Peyser MR. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation. Isr J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;3(suppl):12.-

38. Bishop EH. Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;24:266-268.

39. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin #10. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

40. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Monitoring during induction of labor with dinoprostone. ACOG Committee Opinion #209. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor with misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #228. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

42. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Response to Searle’s drug warning on misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #248. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2000.

- A 16-Foley catheter allows the stiffener to pass through with ease; a 30-mL balloon allows for maximum balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid.

- Hold the Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand, then insert the ripener into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix.

- Position a finger on either side of the cervical opening, slide the catheter into the os until it touches the fetal vertex, and inflate the balloon.

- If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on time of induction.

- The Foley balloon is inexpensive and safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.

Postterm pregnancy, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, perceived intrauterine growth restriction or macrosomia, oligohydramnios—these are just a few of many conditions that may call for induction of labor via cervical ripening. Historically, though, this process has been laborious due to the difficult insertion of mechanical agents and the adverse effects of pharmacologic therapies.

When a urologic sound is added as a stiffener to typical Foley balloon catheter insertion, however, cervical ripening becomes a much simpler, straightforward procedure. Here I will describe proper placement techniques and detail this procedure’s benefits over other, more arduous methods.

A brief history

For many years, only mechanical means of ripening were available. In 1851, the intravaginal colpeurynter was used, followed by various intrauterine metreurynters and pear-shaped inflatable rubber bags inserted through the cervix extra-amniotically. Prolonged traction also was used to effect effacement and dilatation. (FIGURE 1)1,2 Later, natural or artificial laminaria or dilataria were implemented.3 But these mechanical methods fell into disfavor due to placement difficulty and concern about infection. Pharmacologic techniques, including vaginal insertion of gels, suppositories, or off-label oral agents, supplanted these earlier methods. However, the complications and side effects—including hyperstimulation (tachysystole, fetal distress, uterine rupture), nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and fever—were troublesome.

Foley catheter. More than 25 years ago, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania instructed its residents in the standard Foleycatheter–insertion ripening technique. During our residencies there, my colleagues and I found this technique to be “cumbersome, somewhat archaic, and aesthetically suboptimal.”4 In 1995, recognizing the need for a safe, simple, effective, inexpensive, and easily reversible method of ripening with minimal side effects, I revisited the Foley balloon catheter—this time using a urologic sound or stiffener to ease insertion. This coupling transformed the awkward visual positioning of the Foley catheter through the endocervical canal into a straightforward tactile placement, similar in ease of accomplishment to the attachment of a scalp electrode to the fetal vertex.

Several reports in the English-language literature on the specifics of Foley ripening have discussed the use of various catheter sizes (14 Foley to 26 Foley) and balloon capacities (25 mL to 50 mL).5-37 In my practice, I use a 16-Foley catheter, which is large enough for the urologic sound to pass through with ease, and a 30-mL balloon, since a larger balloon may burst in the extra-amniotic space.1 Further, 30 mL—three 10-mL vials—of physiologic saline allows for maximum expansion of balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid (TABLE 1). When balloons are inflated beyond 30 mL, expansion is linear along the catheter tubing, forming a cylindrical rather than spherical shape. Increasing the amount of fluid, therefore, provides no increased pressure on the cervix, but rather, displaces the presenting part.

A literature review reveals that investigators for 2 reports utilized nondescript Foley stiffeners or introducers, but ultimately dismissed them as unnecessary. In fact, the researchers concluded that the Foley stiffener could cause membranes to rupture prematurely.31,32 Since 1995, however, this technique has successfully been utilized in at least 113 patients at our institution. With the use of a blunt-tip stylet, we have not seen any rupture of membranes.

FIGURE 1 Various balloon dilators

TABLE 1

Comparison of instilled PSS (in mL) with Foley balloon circumference (in mm)

| PSS | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| CIRCUMFERENCE | 22 | 61 | 99 | 114 | 122 | 131 | 133 | 138 | 141 | 145 |

| PSS=physiologic saline solution | ||||||||||

Technique

Patient preparation. First, counsel the patient and obtain her informed consent. Prior to examination, ensure that a sonogram reading does not show signs of placenta previa; there are no visible lesions or a history of herpes; and gonorrhea, chlamydia, and group B streptococcus (GBS) cultures are negative. If the GBS culture is positive, provide appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy during the ripening and later induction processes. Routinely examine the patient to elicit a Bishop score and confirm fetal vertex presentation.3 Secure a reactive nonstress test prior to Foley insertion.

Preparing the catheter. Using sterile technique, cut the tip from the 16-Foley catheter just beyond the balloon to allow free egress for the stylet. Perform a leak test by filling the balloon with the standard 30 mL of physiologic saline. Withdraw the saline from the balloon and insert the urologic sound into the catheter.

Foley placement. Hold the trimmed Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand. Then insert the fingers into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix. Position a finger at either side of the cervical opening and place the stylet into the os until it touches the fetal vertex (FIGURE 2). If the catheter does not slide in with the stylet, advance the catheter over the stylet into the extra-amniotic space, using the stylet as a rigid splint to assist in the insertion. Maneuver the tip slightly laterally and inflate the balloon partially while simultaneously withdrawing the stylet. By the time the full 30 mL of physiologic saline has been instilled, the stylet should be completely removed.

Testing insertion. Use your fingers to check that the Foley balloon is completely within the extra-amniotic space. A gentle tug will ensure placement above the internal os. Then push the catheter plug into the open end of the Foley and secure the catheter loosely to the patient’s thigh for comfort. Generally, it is unnecessary to place traction on the Foley catheter to effect effacement and dilatation. If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove the catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on the time of induction.

FIGURE 2 Tactile technique of Foley balloon insertion

Advantages

Cost. For disposable, off-the-shelf catheters, current hospital costs are less than $10. The Van Buren Curve Catheter Stylet (C.R. Bard Inc, Bard Urologic Division, Covington, Ga) is $22 and can be reused after sterilization.

Mechanical agents. The simplified catheter technique is certainly easier than the insertion of multiple laminaria. Laminaria tents are said to require no monitoring post insertion since they produce no uterine contractions and initiate gradual cervical dilatation by mechanical swelling and displacement; thus, they may be used for outpatient ripening and are safe in vaginal birth after cesarean attempts. However, they have been associated with increased postpartum and neonatal infections, along with traumatic insertions and vaginal bleeding. In addition, oxytocin is almost always necessary to initiate labor.35 The Foley catheter, on the other hand, does cause uterine contractions, but has been associated with a lower rate of tachysystole (12.7%) when compared with misoprostol (38.4%).16

While the Foley balloon requires intermittent monitoring—and continuous monitoring should labor become active27—it is still safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.36 No common side effects (intrapartum or postpartum fever and vaginal bleeding,12,18,19,24,26 the quite-rare rupture of membranes, along with displacement of the presenting part and umbilical cord prolapse6,21,37) have been seen with this simplified insertion technique.

Pharmacologic agents. Intracervical or intravaginal prostaglandin E2 (dinoprostone) and oral or intravaginal prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) are effective and simple to administer. However, these agents are not readily reversible; require continuous monitoring once administered; and are fraught with adverse effects, including fever, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperstimulation that may lead to tachysystole, uterine rupture, and fetal morbidity and mortality.39-42

Conclusion

Until further controlled studies documenting outpatient safety are available, balloon ripening should be limited to an in-hospital technique, as it causes uterine contractions and even tachysystole.18,4 In the meantime, clinicians should feel confident including this simplified technique in their obstetric armamentarium.

Dr. Freedman reports no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

- A 16-Foley catheter allows the stiffener to pass through with ease; a 30-mL balloon allows for maximum balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid.

- Hold the Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand, then insert the ripener into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix.

- Position a finger on either side of the cervical opening, slide the catheter into the os until it touches the fetal vertex, and inflate the balloon.

- If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on time of induction.

- The Foley balloon is inexpensive and safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.

Postterm pregnancy, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, perceived intrauterine growth restriction or macrosomia, oligohydramnios—these are just a few of many conditions that may call for induction of labor via cervical ripening. Historically, though, this process has been laborious due to the difficult insertion of mechanical agents and the adverse effects of pharmacologic therapies.

When a urologic sound is added as a stiffener to typical Foley balloon catheter insertion, however, cervical ripening becomes a much simpler, straightforward procedure. Here I will describe proper placement techniques and detail this procedure’s benefits over other, more arduous methods.

A brief history

For many years, only mechanical means of ripening were available. In 1851, the intravaginal colpeurynter was used, followed by various intrauterine metreurynters and pear-shaped inflatable rubber bags inserted through the cervix extra-amniotically. Prolonged traction also was used to effect effacement and dilatation. (FIGURE 1)1,2 Later, natural or artificial laminaria or dilataria were implemented.3 But these mechanical methods fell into disfavor due to placement difficulty and concern about infection. Pharmacologic techniques, including vaginal insertion of gels, suppositories, or off-label oral agents, supplanted these earlier methods. However, the complications and side effects—including hyperstimulation (tachysystole, fetal distress, uterine rupture), nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and fever—were troublesome.

Foley catheter. More than 25 years ago, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania instructed its residents in the standard Foleycatheter–insertion ripening technique. During our residencies there, my colleagues and I found this technique to be “cumbersome, somewhat archaic, and aesthetically suboptimal.”4 In 1995, recognizing the need for a safe, simple, effective, inexpensive, and easily reversible method of ripening with minimal side effects, I revisited the Foley balloon catheter—this time using a urologic sound or stiffener to ease insertion. This coupling transformed the awkward visual positioning of the Foley catheter through the endocervical canal into a straightforward tactile placement, similar in ease of accomplishment to the attachment of a scalp electrode to the fetal vertex.

Several reports in the English-language literature on the specifics of Foley ripening have discussed the use of various catheter sizes (14 Foley to 26 Foley) and balloon capacities (25 mL to 50 mL).5-37 In my practice, I use a 16-Foley catheter, which is large enough for the urologic sound to pass through with ease, and a 30-mL balloon, since a larger balloon may burst in the extra-amniotic space.1 Further, 30 mL—three 10-mL vials—of physiologic saline allows for maximum expansion of balloon circumference utilizing a minimal amount of fluid (TABLE 1). When balloons are inflated beyond 30 mL, expansion is linear along the catheter tubing, forming a cylindrical rather than spherical shape. Increasing the amount of fluid, therefore, provides no increased pressure on the cervix, but rather, displaces the presenting part.

A literature review reveals that investigators for 2 reports utilized nondescript Foley stiffeners or introducers, but ultimately dismissed them as unnecessary. In fact, the researchers concluded that the Foley stiffener could cause membranes to rupture prematurely.31,32 Since 1995, however, this technique has successfully been utilized in at least 113 patients at our institution. With the use of a blunt-tip stylet, we have not seen any rupture of membranes.

FIGURE 1 Various balloon dilators

TABLE 1

Comparison of instilled PSS (in mL) with Foley balloon circumference (in mm)

| PSS | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| CIRCUMFERENCE | 22 | 61 | 99 | 114 | 122 | 131 | 133 | 138 | 141 | 145 |

| PSS=physiologic saline solution | ||||||||||

Technique

Patient preparation. First, counsel the patient and obtain her informed consent. Prior to examination, ensure that a sonogram reading does not show signs of placenta previa; there are no visible lesions or a history of herpes; and gonorrhea, chlamydia, and group B streptococcus (GBS) cultures are negative. If the GBS culture is positive, provide appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy during the ripening and later induction processes. Routinely examine the patient to elicit a Bishop score and confirm fetal vertex presentation.3 Secure a reactive nonstress test prior to Foley insertion.

Preparing the catheter. Using sterile technique, cut the tip from the 16-Foley catheter just beyond the balloon to allow free egress for the stylet. Perform a leak test by filling the balloon with the standard 30 mL of physiologic saline. Withdraw the saline from the balloon and insert the urologic sound into the catheter.

Foley placement. Hold the trimmed Foley catheter with internal stylet between the first 2 fingers of your dominant hand. Then insert the fingers into the patient’s vagina up to the cervix. Position a finger at either side of the cervical opening and place the stylet into the os until it touches the fetal vertex (FIGURE 2). If the catheter does not slide in with the stylet, advance the catheter over the stylet into the extra-amniotic space, using the stylet as a rigid splint to assist in the insertion. Maneuver the tip slightly laterally and inflate the balloon partially while simultaneously withdrawing the stylet. By the time the full 30 mL of physiologic saline has been instilled, the stylet should be completely removed.

Testing insertion. Use your fingers to check that the Foley balloon is completely within the extra-amniotic space. A gentle tug will ensure placement above the internal os. Then push the catheter plug into the open end of the Foley and secure the catheter loosely to the patient’s thigh for comfort. Generally, it is unnecessary to place traction on the Foley catheter to effect effacement and dilatation. If the Foley is not spontaneously expelled, deflate the balloon and remove the catheter within 5 to 12 hours, depending on the time of induction.

FIGURE 2 Tactile technique of Foley balloon insertion

Advantages

Cost. For disposable, off-the-shelf catheters, current hospital costs are less than $10. The Van Buren Curve Catheter Stylet (C.R. Bard Inc, Bard Urologic Division, Covington, Ga) is $22 and can be reused after sterilization.

Mechanical agents. The simplified catheter technique is certainly easier than the insertion of multiple laminaria. Laminaria tents are said to require no monitoring post insertion since they produce no uterine contractions and initiate gradual cervical dilatation by mechanical swelling and displacement; thus, they may be used for outpatient ripening and are safe in vaginal birth after cesarean attempts. However, they have been associated with increased postpartum and neonatal infections, along with traumatic insertions and vaginal bleeding. In addition, oxytocin is almost always necessary to initiate labor.35 The Foley catheter, on the other hand, does cause uterine contractions, but has been associated with a lower rate of tachysystole (12.7%) when compared with misoprostol (38.4%).16

While the Foley balloon requires intermittent monitoring—and continuous monitoring should labor become active27—it is still safe to use after ruptured membranes or in a trial of labor following a previous cesarean.36 No common side effects (intrapartum or postpartum fever and vaginal bleeding,12,18,19,24,26 the quite-rare rupture of membranes, along with displacement of the presenting part and umbilical cord prolapse6,21,37) have been seen with this simplified insertion technique.

Pharmacologic agents. Intracervical or intravaginal prostaglandin E2 (dinoprostone) and oral or intravaginal prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) are effective and simple to administer. However, these agents are not readily reversible; require continuous monitoring once administered; and are fraught with adverse effects, including fever, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperstimulation that may lead to tachysystole, uterine rupture, and fetal morbidity and mortality.39-42

Conclusion

Until further controlled studies documenting outpatient safety are available, balloon ripening should be limited to an in-hospital technique, as it causes uterine contractions and even tachysystole.18,4 In the meantime, clinicians should feel confident including this simplified technique in their obstetric armamentarium.

Dr. Freedman reports no affiliation or financial arrangement with any of the companies that manufacture drugs or devices in any of the product classes mentioned in this article.

1. DeLee JB. The Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1913;911-914.

2. Munro Kerr JM, Johnstone RW, Phillips MH (eds). Historical Review of British Obstetrics and Gynecology 1800-1950. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1954;81.-

3. Johnson N. Seaweed and its synthetic analogues in obstetrics and gynecology 450 BC–1990 AD. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:387-389.

4. Trofatter KF. Cervical ripening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;35:476-486.

5. Newton ER. Using mechanical dilators for cervical ripening. Contemp Ob Gyn. December 1987;47-64.

6. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Tovbin J, Arieli S, Caspi E, Bukovsky I. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic catheter balloon: clinical experience and review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:621-627.

7. Poma PA. Cervical ripening: a review and recommendations for clinical practice. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:657-668.

8. Sciscione AC, Pollock M. Preinduction cervical ripening using the Foley catheter. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2000;20(24):1-6.

9. Abramovici D, Goldwasser S, Mabie BC, Mercer BM, Goldwasser R, Sibai BM. A randomized comparison of oral misoprostol versus Foley catheter and oxytocin for induction of labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1108-1112.

10. Atad J, Bornstein J, Calderon I, Petrikovsky BM, Sorokin Y, Abramovici H. Nonpharmaceutical ripening of the unfavorable cervix and induction of labor by a novel double balloon device. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:146-152.

11. Atad J, Hallek M, Ben David Y, Auslander R, Abramovici H. Ripening and dilatation of the unfavorable cervix for induction of labor by a double balloon device: experience with 250 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:29-32.

12. Embrey MP, Mollison BG. The unfavorable cervix and induction using a cervical balloon. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1967;74:44-48.

13. Ezimokhai M, Nwabineli JN. The use of Foley’s catheter in ripening the unfavorable cervix prior to the induction of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:281-286.

14. George SS, Matthews J, Jeyaseelan L, Seshadri L. Cervical ripening induces labor through interleukin 1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;33:285-286.

15. Goldman JB, Wigton TR. A randomized comparison of extra-amniotic saline infusion and intracervical dinoprostone gel for cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

16. Greybush M, Singleton C, Atlas RO, Balducci J, Rust OA. Preinduction cervical ripening techniques compared. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:11-17.

17. Guinn DA, Goepfert AR, Christine M, Owen J, Hauth JC. Extra-amniotic saline, laminaria, or prostaglandin E2 for labor induction with unfavorable cervix: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

18. James C, Peedicayil A, Seshardi L. Use of the Foley catheter as a cervical ripening agent prior to induction of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;47:229-232.

19. Lieberman JR, Piura B, Chaim W, Cohen A. The cervical balloon method for induction of labour. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:499-503.

20. Lurie S, Rabinerson D. Balloon ripening of the cervix [letter]. Lancet. 1997;349:509.-

21. Mahomed K. Foley catheter under traction versus extra-amniotic prostaglandin gel in pre-treatment of the unripe cervix: A randomized, controlled trial. East Afr Med J. 1988;34:98-102.

22. Orhue AAE. Induction of labour at term in primigravidae with low Bishop’s score: a comparison of methods. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;58:119-125.

23. Perry KG, Larmon JE, May WL, Robinette LG, Martin RW. Cervical ripening: a randomized comparison between intravaginal misoprostol and an intracervical balloon catheter combined with intravaginal dinoprostone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1333-1340.

24. Rouben D, Arias F. A randomized trial of extra-amniotic saline infusion plus intracervical Foley catheter balloon versus prostaglandin E2 vaginal gel for ripening the cervix and inducing labor in patients with unfavorable cervixes. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:290-294.

25. Sandhu SK, Tung R. Use of Foley’s catheter to improve the cervical score prior to induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 1984;34:669-672.

26. Schreyer P, Sherman DJ, Ariely S, Herman A, Caspi E. Ripening of the highly unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation or vaginal prostaglandin E2 application. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:938-942.

27. Sciscione AC, McCullough H, Manley JS, Shlossman PA, Pollock M, Colmorgen GHC. A prospective, randomized comparison of Foley catheter insertion versus intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel for preinduction cervical ripening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:55-59.

28. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Pansky M, Caspi E, Bukovsky I, Langer R. Balloon cervical ripening with extra-amniotic infusion of saline or prostaglandin E2: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:375-380.

29. St. Onge RD, Connors GT. Pre-induction cervical ripening: a comparison of intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel versus the Foley catheter. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:687-690.

30. Sullivan CA, Benton LW, Roach H, Smith LG, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Combining medical and mechanical methods of cervical ripening: Does it increase the likelihood of successful induction of labor? J Reprod Med. 1996;41:823-828.

31. Thiery M. Pre-induction cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol Ann. 1983;12:103-146.

32. Thomas IL, Chenoweth JN, Tronc GN, Johnson IR. Preparation for induction of labour of the unfavorable cervix with Foley catheter compared with vaginal prostaglandin. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;26:30-35.

33. Vergalil SR, Guinn DA, Olabi NF, Burd LI, Owen J. A randomized trial of misoprostol and extra-amniotic saline infusion for cervical ripening and labor induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:774-779.

34. Wilson PD. A comparison of four methods of ripening the unfavorable cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978;85:941-944.

35. Witter FR. Cervical ripening for labor induction. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2001;21(3):1-4.

36. Wolff K, Swahn ML, Westgren M. Balloon catheter for induction of labor in nulliparous women with prelabor rupture of the membranes at term: a preliminary report. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:1-4.

37. Yaron Y, Kupfermic MJ, Peyser MR. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation. Isr J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;3(suppl):12.-

38. Bishop EH. Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;24:266-268.

39. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin #10. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

40. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Monitoring during induction of labor with dinoprostone. ACOG Committee Opinion #209. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor with misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #228. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

42. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Response to Searle’s drug warning on misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #248. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2000.

1. DeLee JB. The Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1913;911-914.

2. Munro Kerr JM, Johnstone RW, Phillips MH (eds). Historical Review of British Obstetrics and Gynecology 1800-1950. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1954;81.-

3. Johnson N. Seaweed and its synthetic analogues in obstetrics and gynecology 450 BC–1990 AD. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:387-389.

4. Trofatter KF. Cervical ripening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;35:476-486.

5. Newton ER. Using mechanical dilators for cervical ripening. Contemp Ob Gyn. December 1987;47-64.

6. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Tovbin J, Arieli S, Caspi E, Bukovsky I. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic catheter balloon: clinical experience and review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:621-627.

7. Poma PA. Cervical ripening: a review and recommendations for clinical practice. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:657-668.

8. Sciscione AC, Pollock M. Preinduction cervical ripening using the Foley catheter. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2000;20(24):1-6.

9. Abramovici D, Goldwasser S, Mabie BC, Mercer BM, Goldwasser R, Sibai BM. A randomized comparison of oral misoprostol versus Foley catheter and oxytocin for induction of labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1108-1112.

10. Atad J, Bornstein J, Calderon I, Petrikovsky BM, Sorokin Y, Abramovici H. Nonpharmaceutical ripening of the unfavorable cervix and induction of labor by a novel double balloon device. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:146-152.

11. Atad J, Hallek M, Ben David Y, Auslander R, Abramovici H. Ripening and dilatation of the unfavorable cervix for induction of labor by a double balloon device: experience with 250 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:29-32.

12. Embrey MP, Mollison BG. The unfavorable cervix and induction using a cervical balloon. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1967;74:44-48.

13. Ezimokhai M, Nwabineli JN. The use of Foley’s catheter in ripening the unfavorable cervix prior to the induction of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:281-286.

14. George SS, Matthews J, Jeyaseelan L, Seshadri L. Cervical ripening induces labor through interleukin 1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;33:285-286.

15. Goldman JB, Wigton TR. A randomized comparison of extra-amniotic saline infusion and intracervical dinoprostone gel for cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

16. Greybush M, Singleton C, Atlas RO, Balducci J, Rust OA. Preinduction cervical ripening techniques compared. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:11-17.

17. Guinn DA, Goepfert AR, Christine M, Owen J, Hauth JC. Extra-amniotic saline, laminaria, or prostaglandin E2 for labor induction with unfavorable cervix: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:271-274.

18. James C, Peedicayil A, Seshardi L. Use of the Foley catheter as a cervical ripening agent prior to induction of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;47:229-232.

19. Lieberman JR, Piura B, Chaim W, Cohen A. The cervical balloon method for induction of labour. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:499-503.

20. Lurie S, Rabinerson D. Balloon ripening of the cervix [letter]. Lancet. 1997;349:509.-

21. Mahomed K. Foley catheter under traction versus extra-amniotic prostaglandin gel in pre-treatment of the unripe cervix: A randomized, controlled trial. East Afr Med J. 1988;34:98-102.

22. Orhue AAE. Induction of labour at term in primigravidae with low Bishop’s score: a comparison of methods. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;58:119-125.

23. Perry KG, Larmon JE, May WL, Robinette LG, Martin RW. Cervical ripening: a randomized comparison between intravaginal misoprostol and an intracervical balloon catheter combined with intravaginal dinoprostone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1333-1340.

24. Rouben D, Arias F. A randomized trial of extra-amniotic saline infusion plus intracervical Foley catheter balloon versus prostaglandin E2 vaginal gel for ripening the cervix and inducing labor in patients with unfavorable cervixes. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:290-294.

25. Sandhu SK, Tung R. Use of Foley’s catheter to improve the cervical score prior to induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 1984;34:669-672.

26. Schreyer P, Sherman DJ, Ariely S, Herman A, Caspi E. Ripening of the highly unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation or vaginal prostaglandin E2 application. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:938-942.

27. Sciscione AC, McCullough H, Manley JS, Shlossman PA, Pollock M, Colmorgen GHC. A prospective, randomized comparison of Foley catheter insertion versus intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel for preinduction cervical ripening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:55-59.

28. Sherman DJ, Frenkel E, Pansky M, Caspi E, Bukovsky I, Langer R. Balloon cervical ripening with extra-amniotic infusion of saline or prostaglandin E2: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:375-380.

29. St. Onge RD, Connors GT. Pre-induction cervical ripening: a comparison of intracervical prostaglandin E2 gel versus the Foley catheter. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:687-690.

30. Sullivan CA, Benton LW, Roach H, Smith LG, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Combining medical and mechanical methods of cervical ripening: Does it increase the likelihood of successful induction of labor? J Reprod Med. 1996;41:823-828.

31. Thiery M. Pre-induction cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol Ann. 1983;12:103-146.

32. Thomas IL, Chenoweth JN, Tronc GN, Johnson IR. Preparation for induction of labour of the unfavorable cervix with Foley catheter compared with vaginal prostaglandin. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;26:30-35.

33. Vergalil SR, Guinn DA, Olabi NF, Burd LI, Owen J. A randomized trial of misoprostol and extra-amniotic saline infusion for cervical ripening and labor induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:774-779.

34. Wilson PD. A comparison of four methods of ripening the unfavorable cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978;85:941-944.

35. Witter FR. Cervical ripening for labor induction. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol. 2001;21(3):1-4.

36. Wolff K, Swahn ML, Westgren M. Balloon catheter for induction of labor in nulliparous women with prelabor rupture of the membranes at term: a preliminary report. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:1-4.

37. Yaron Y, Kupfermic MJ, Peyser MR. Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extra-amniotic saline installation. Isr J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;3(suppl):12.-

38. Bishop EH. Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;24:266-268.

39. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin #10. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

40. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Monitoring during induction of labor with dinoprostone. ACOG Committee Opinion #209. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Induction of labor with misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #228. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1999.

42. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Response to Searle’s drug warning on misoprostol. ACOG Committee Opinion #248. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2000.