User login

NEW ORLEANS – Midwife-attended home births appear to have a higher mortality rate than midwife-attended hospital births, a new national database study suggests.

But for both physicians and families, the findings lie at the center of a tangled knot of statistics, philosophy, fear, and determination.

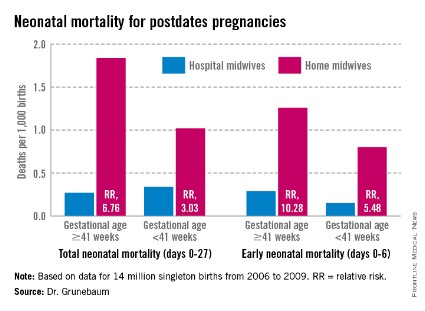

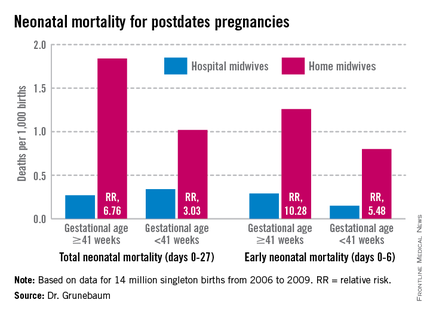

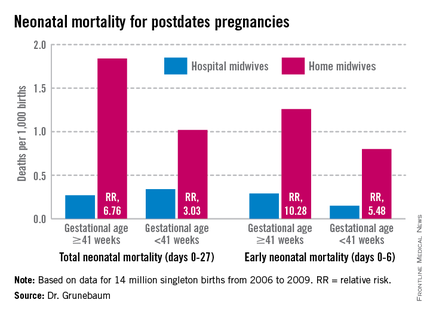

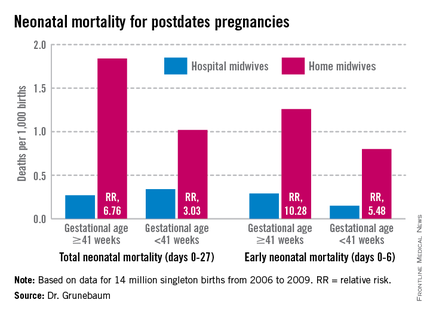

According to a new study of national birth and death statistics, total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk, Dr. Amos Grunebaum said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

His study drew its data from linked birth and death records available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) database. The study looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009. Only healthy singleton infants of normal birth weight and vertex presentation were included; gestation was 38-42 weeks.

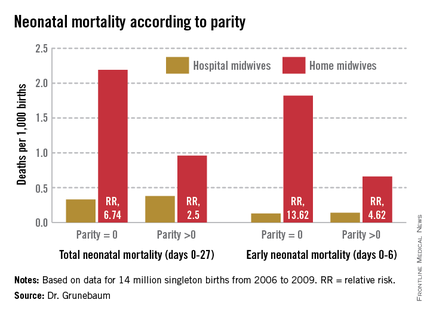

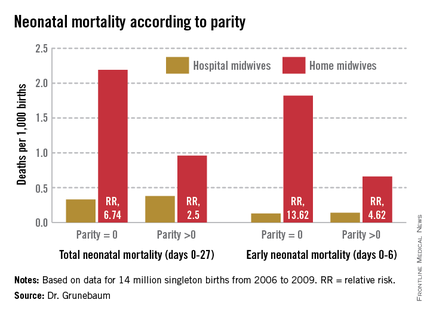

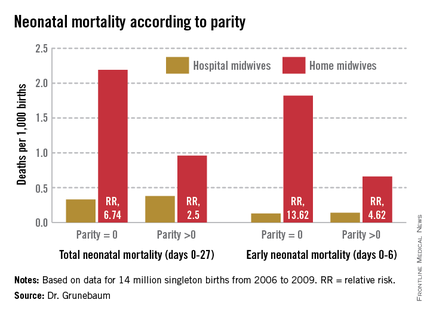

The figures for nulliparous women giving birth at home were even more striking, said Dr. Grunebaum, director of obstetrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Total neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 27) was 2.19/1,000 for home-birthed infants, compared with 0.38/1,000 for hospital-born infants (relative risk, 6.74). The rates of early neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 6) were 1.82/1,000 vs. 0.13/1,000, respectively (RR, 13.6).

"When we calculate the excess total neonatal deaths associated with home birth, we arrive at 9/10,000," he said during an interview. "If the trend of increasing home birth holds over the next few years, in 2016 we could have 32 excess neonatal deaths per year – a whole school class of children."

"It’s possible these risks are even higher," he added, because any babies born in the hospital after an emergency transfer from home are counted as hospital births.

It’s tough to parse out the details in his analysis, however. Because lay midwives would never have had hospital privileges, the in-hospital midwife group was likely composed entirely of certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), whose specialized training makes them highly skilled birth attendants. But the midwives who attended home births were a heterogenous group. In addition to CNMs, the analysis included anyone else who would register as "midwife" on a birth certificate – a group that represents an extremely varied range of skill.

These attendants could be could have been CNMs, certified midwives, certified professional midwives, licensed midwives, or lay midwives. CNMs must have a bachelor’s degree as a registered nurse and then graduate from an accredited school of nurse-midwifery. A certified midwife is a graduate of the same school of midwifery program, but can hold a degree in a field other than nursing. The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) regulates these providers.

No college degree is required for a certified professional midwife. They can obtain licensure based on an apprenticeship portfolio or from other schools of midwifery. The Midwives Alliance of North America and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives regulate this group. Lay midwives are allowed to practice in some states, but there is no regulatory board, and no licensure or educational requirements.

In all probability, very few CNMs attended the home births in Dr. Grunebaum’s study, according to Jesse Bushman, ACNM’s director of advocacy and government affairs. The college’s own data indicate that 90% of deliveries performed by members are in hospitals. Only 30% of home births recorded in the CDC data were performed by CNMs, he said.

"That is one issue we have with Dr. Grunebaum’s results," Mr. Bushman* said in an interview. "There are many people who could call themselves a midwife who may not have the training or competencies that CNMs do. To lump them together is quite problematic."

In an interview, Dr. Grunebaum said that he had parsed out the mortality results by specific provider group. However, he would not release those numbers, saying it could jeopardize his study’s peer-reviewed publication. "I will tell you that CNMs at home did much, much worse than CNMs in the hospital, and that other midwives at home were not far behind."

Birth outcomes data just released by the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) align with Dr. Grunebaum’s numbers (J. Midwifery Womens Health 2014 Jan. 30 [doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12172]). But the interpretation – if not the numbers – lies in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Grunebaum said the study illustrates the danger of home birth. MANA hailed it as proof of home birth’s safety.

"The results of this study ... confirm the safety and overwhelmingly positive health benefits for low-risk mothers and babies who choose to birth at home with a midwife," the group noted on its website. "At every step of the way, midwives are providing excellent care. This study enables families, providers, and policy makers to have a transparent look at the risks and benefits of planned home birth, as well as the health benefits of normal physiologic birth."

The study was a voluntary survey that examined data from almost 17,000 home births. The voluntary nature troubles Dr. Grunebaum, who pointed out that midwives with poor outcomes probably would not have submitted data.

There was an 11% hospital transfer rate in the cohort from the midwives study. There were 43 fetal deaths in the intrapartum, early, and late neonatal periods; 8 of these were from lethal congenital defects. The remaining deaths translated to a total neonatal mortality rate of 1.3/1,000.

Twenty-two died during labor, but before birth. For 13, the causes were known: placental abruption (2), intrauterine infection (2), cord accidents (3), complications of maternal gestational diabetes (2), meconium aspiration (1), shoulder dystocia (1), complications of preeclampsia (1), and liver rupture and hypoxia (1).

Seven babies died during the first 6 days of life. The causes were secondary to cord accidents (2, one with shoulder dystocia), and hypoxia or ischemia of unknown origin (5).

Six infants died in the late neonatal period. Two deaths were secondary to cord accidents, and four were from unknown causes.

Of 222 breech births, three infants died (13/1,000). Of 3,773 births to primiparous women, 11 infants died (2.9/1,000). Of 1,052 attempted vaginal births, 3 infants died (2.85/1,000)

"These numbers are horrible," Dr. Grunebaum said. "There is no longer room for the argument from home birth supporters that while the risk may be increased, it’s still very low in terms of absolute risk."

"This view has even been expressed by our own specialists," he added, referring to an American Academy of Pediatrics position paper on planned home birth (Pediatrics 2013;131:1016-20). While maintaining that birth is safest in a hospital or birthing center, the paper acknowledges that the two- or threefold overall increase in mortality associated with home birth is low – generally translating to about 1 in 1,000 newborns.

"That minimizes the extra risk involved in home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "We should have no acceptance for any increase in death or injury in exchange for parental convenience or for fewer interventions. We need to disclose these increased risks to mothers, and perform direct counseling against home birth."

His study fans a long-simmering debate about the best places to birth. Proponents of both philosophies want the same primary outcome: healthy mothers and infants. The debate? How to best get there.

Midwife-assisted home birth has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to CDC data, there were about 16,000 in 2007; by 2012, it was about 23,500. The rise is mostly seen in a very specific demographic – well-educated, financially secure white women with at least one other child who was, most frequently, born in a hospital.

Dr. Grunebaum attributed the rise to some women’s desire to avoid what they perceive as intrusive labor and birth management. With this thought, at least, others do agree.

Eugene DeClercq, Ph.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health at Boston University, has worked on three national surveys that poll new mothers about their experiences with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum life.

Childbirth Connection (childbirthconnection.org) conducted the Listening to Mothers surveys in 2002, 2006, and 2012. The survey reports are intended to serve as policy resources for improving the childbearing experience for women and their families.

"One of the real questions we need to look at is, what’s going on in hospitals that makes women consider giving birth outside the hospital," Dr. DeClercq said in an interview. "What has come through in our interviews is that many women are quite fine with the ways things go in a hospital. They are for any intervention that they think will make a safer birth. But many women are not. They report feeling pressured to have interventions, and worried that one will lead to another and another, in a cascade that can eventually end up in a cesarean section."

This is a legitimate concern in the United States, he said – a country in which the cesarean rate hovers around 30%, and ranges from 7% to 70% across hospitals. "If you lived ... where there was a 70% rate of cesarean – 70%! – might you be thinking about some way to avoid that?"

In the Listening to Mothers II survey, women were asked a series of questions about their experiences with labor and delivery. The results of the survey revealed that 47% of first-time mothers were induced. "Of those having an induction, 78% had an epidural, and of those mothers who had both an attempted induction and an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 31%," the report noted. "Those who experienced either labor induction or an epidural, but not both, had cesarean rates of 19% to 20%. For those first-time mothers who experienced neither attempted induction nor an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 5%."

Like it or not, he said, some women will go to almost any length to avoid interventions they fear may harm them and their babies.

The Listening to Mothers survey found that a quarter of women who had given birth in a hospital would consider a home birth. Most women in the survey (2/3) said a woman should be able to have a home birth if she wanted, and 11% said they would definitely want a home birth.

"If you look at the profile of home-birthers, it’s not like they are some crazy fringe group," Dr. DeClercq said. "These are very well-educated women, 75% of whom have already had a hospital birth. They are researching and weighing the pros and cons. They’re not just making some random decision."

His data also suggest that women who transfer to a hospital from a home birth fear judgment and even recrimination. "The consequences of that can be a delay in transfer when it’s necessary, and can lead to problems," even poor infant outcomes.

On this point at least, the two sides find common ground.

"Most of us will never attend a home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "But we will encounter patients asking us about home births and seeking hospital transfer for successful or complicated home births, and babies transferred after a home birth. And for these we need to provide compassionate, nonjudgmental care."

None of the sources interviewed for this story reported any financial disclosures.

*Correction, 3/4/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated Mr. Bushman's name.

NEW ORLEANS – Midwife-attended home births appear to have a higher mortality rate than midwife-attended hospital births, a new national database study suggests.

But for both physicians and families, the findings lie at the center of a tangled knot of statistics, philosophy, fear, and determination.

According to a new study of national birth and death statistics, total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk, Dr. Amos Grunebaum said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

His study drew its data from linked birth and death records available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) database. The study looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009. Only healthy singleton infants of normal birth weight and vertex presentation were included; gestation was 38-42 weeks.

The figures for nulliparous women giving birth at home were even more striking, said Dr. Grunebaum, director of obstetrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Total neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 27) was 2.19/1,000 for home-birthed infants, compared with 0.38/1,000 for hospital-born infants (relative risk, 6.74). The rates of early neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 6) were 1.82/1,000 vs. 0.13/1,000, respectively (RR, 13.6).

"When we calculate the excess total neonatal deaths associated with home birth, we arrive at 9/10,000," he said during an interview. "If the trend of increasing home birth holds over the next few years, in 2016 we could have 32 excess neonatal deaths per year – a whole school class of children."

"It’s possible these risks are even higher," he added, because any babies born in the hospital after an emergency transfer from home are counted as hospital births.

It’s tough to parse out the details in his analysis, however. Because lay midwives would never have had hospital privileges, the in-hospital midwife group was likely composed entirely of certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), whose specialized training makes them highly skilled birth attendants. But the midwives who attended home births were a heterogenous group. In addition to CNMs, the analysis included anyone else who would register as "midwife" on a birth certificate – a group that represents an extremely varied range of skill.

These attendants could be could have been CNMs, certified midwives, certified professional midwives, licensed midwives, or lay midwives. CNMs must have a bachelor’s degree as a registered nurse and then graduate from an accredited school of nurse-midwifery. A certified midwife is a graduate of the same school of midwifery program, but can hold a degree in a field other than nursing. The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) regulates these providers.

No college degree is required for a certified professional midwife. They can obtain licensure based on an apprenticeship portfolio or from other schools of midwifery. The Midwives Alliance of North America and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives regulate this group. Lay midwives are allowed to practice in some states, but there is no regulatory board, and no licensure or educational requirements.

In all probability, very few CNMs attended the home births in Dr. Grunebaum’s study, according to Jesse Bushman, ACNM’s director of advocacy and government affairs. The college’s own data indicate that 90% of deliveries performed by members are in hospitals. Only 30% of home births recorded in the CDC data were performed by CNMs, he said.

"That is one issue we have with Dr. Grunebaum’s results," Mr. Bushman* said in an interview. "There are many people who could call themselves a midwife who may not have the training or competencies that CNMs do. To lump them together is quite problematic."

In an interview, Dr. Grunebaum said that he had parsed out the mortality results by specific provider group. However, he would not release those numbers, saying it could jeopardize his study’s peer-reviewed publication. "I will tell you that CNMs at home did much, much worse than CNMs in the hospital, and that other midwives at home were not far behind."

Birth outcomes data just released by the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) align with Dr. Grunebaum’s numbers (J. Midwifery Womens Health 2014 Jan. 30 [doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12172]). But the interpretation – if not the numbers – lies in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Grunebaum said the study illustrates the danger of home birth. MANA hailed it as proof of home birth’s safety.

"The results of this study ... confirm the safety and overwhelmingly positive health benefits for low-risk mothers and babies who choose to birth at home with a midwife," the group noted on its website. "At every step of the way, midwives are providing excellent care. This study enables families, providers, and policy makers to have a transparent look at the risks and benefits of planned home birth, as well as the health benefits of normal physiologic birth."

The study was a voluntary survey that examined data from almost 17,000 home births. The voluntary nature troubles Dr. Grunebaum, who pointed out that midwives with poor outcomes probably would not have submitted data.

There was an 11% hospital transfer rate in the cohort from the midwives study. There were 43 fetal deaths in the intrapartum, early, and late neonatal periods; 8 of these were from lethal congenital defects. The remaining deaths translated to a total neonatal mortality rate of 1.3/1,000.

Twenty-two died during labor, but before birth. For 13, the causes were known: placental abruption (2), intrauterine infection (2), cord accidents (3), complications of maternal gestational diabetes (2), meconium aspiration (1), shoulder dystocia (1), complications of preeclampsia (1), and liver rupture and hypoxia (1).

Seven babies died during the first 6 days of life. The causes were secondary to cord accidents (2, one with shoulder dystocia), and hypoxia or ischemia of unknown origin (5).

Six infants died in the late neonatal period. Two deaths were secondary to cord accidents, and four were from unknown causes.

Of 222 breech births, three infants died (13/1,000). Of 3,773 births to primiparous women, 11 infants died (2.9/1,000). Of 1,052 attempted vaginal births, 3 infants died (2.85/1,000)

"These numbers are horrible," Dr. Grunebaum said. "There is no longer room for the argument from home birth supporters that while the risk may be increased, it’s still very low in terms of absolute risk."

"This view has even been expressed by our own specialists," he added, referring to an American Academy of Pediatrics position paper on planned home birth (Pediatrics 2013;131:1016-20). While maintaining that birth is safest in a hospital or birthing center, the paper acknowledges that the two- or threefold overall increase in mortality associated with home birth is low – generally translating to about 1 in 1,000 newborns.

"That minimizes the extra risk involved in home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "We should have no acceptance for any increase in death or injury in exchange for parental convenience or for fewer interventions. We need to disclose these increased risks to mothers, and perform direct counseling against home birth."

His study fans a long-simmering debate about the best places to birth. Proponents of both philosophies want the same primary outcome: healthy mothers and infants. The debate? How to best get there.

Midwife-assisted home birth has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to CDC data, there were about 16,000 in 2007; by 2012, it was about 23,500. The rise is mostly seen in a very specific demographic – well-educated, financially secure white women with at least one other child who was, most frequently, born in a hospital.

Dr. Grunebaum attributed the rise to some women’s desire to avoid what they perceive as intrusive labor and birth management. With this thought, at least, others do agree.

Eugene DeClercq, Ph.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health at Boston University, has worked on three national surveys that poll new mothers about their experiences with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum life.

Childbirth Connection (childbirthconnection.org) conducted the Listening to Mothers surveys in 2002, 2006, and 2012. The survey reports are intended to serve as policy resources for improving the childbearing experience for women and their families.

"One of the real questions we need to look at is, what’s going on in hospitals that makes women consider giving birth outside the hospital," Dr. DeClercq said in an interview. "What has come through in our interviews is that many women are quite fine with the ways things go in a hospital. They are for any intervention that they think will make a safer birth. But many women are not. They report feeling pressured to have interventions, and worried that one will lead to another and another, in a cascade that can eventually end up in a cesarean section."

This is a legitimate concern in the United States, he said – a country in which the cesarean rate hovers around 30%, and ranges from 7% to 70% across hospitals. "If you lived ... where there was a 70% rate of cesarean – 70%! – might you be thinking about some way to avoid that?"

In the Listening to Mothers II survey, women were asked a series of questions about their experiences with labor and delivery. The results of the survey revealed that 47% of first-time mothers were induced. "Of those having an induction, 78% had an epidural, and of those mothers who had both an attempted induction and an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 31%," the report noted. "Those who experienced either labor induction or an epidural, but not both, had cesarean rates of 19% to 20%. For those first-time mothers who experienced neither attempted induction nor an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 5%."

Like it or not, he said, some women will go to almost any length to avoid interventions they fear may harm them and their babies.

The Listening to Mothers survey found that a quarter of women who had given birth in a hospital would consider a home birth. Most women in the survey (2/3) said a woman should be able to have a home birth if she wanted, and 11% said they would definitely want a home birth.

"If you look at the profile of home-birthers, it’s not like they are some crazy fringe group," Dr. DeClercq said. "These are very well-educated women, 75% of whom have already had a hospital birth. They are researching and weighing the pros and cons. They’re not just making some random decision."

His data also suggest that women who transfer to a hospital from a home birth fear judgment and even recrimination. "The consequences of that can be a delay in transfer when it’s necessary, and can lead to problems," even poor infant outcomes.

On this point at least, the two sides find common ground.

"Most of us will never attend a home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "But we will encounter patients asking us about home births and seeking hospital transfer for successful or complicated home births, and babies transferred after a home birth. And for these we need to provide compassionate, nonjudgmental care."

None of the sources interviewed for this story reported any financial disclosures.

*Correction, 3/4/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated Mr. Bushman's name.

NEW ORLEANS – Midwife-attended home births appear to have a higher mortality rate than midwife-attended hospital births, a new national database study suggests.

But for both physicians and families, the findings lie at the center of a tangled knot of statistics, philosophy, fear, and determination.

According to a new study of national birth and death statistics, total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk, Dr. Amos Grunebaum said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

His study drew its data from linked birth and death records available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) database. The study looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009. Only healthy singleton infants of normal birth weight and vertex presentation were included; gestation was 38-42 weeks.

The figures for nulliparous women giving birth at home were even more striking, said Dr. Grunebaum, director of obstetrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Total neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 27) was 2.19/1,000 for home-birthed infants, compared with 0.38/1,000 for hospital-born infants (relative risk, 6.74). The rates of early neonatal mortality (deaths from day 0 to 6) were 1.82/1,000 vs. 0.13/1,000, respectively (RR, 13.6).

"When we calculate the excess total neonatal deaths associated with home birth, we arrive at 9/10,000," he said during an interview. "If the trend of increasing home birth holds over the next few years, in 2016 we could have 32 excess neonatal deaths per year – a whole school class of children."

"It’s possible these risks are even higher," he added, because any babies born in the hospital after an emergency transfer from home are counted as hospital births.

It’s tough to parse out the details in his analysis, however. Because lay midwives would never have had hospital privileges, the in-hospital midwife group was likely composed entirely of certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), whose specialized training makes them highly skilled birth attendants. But the midwives who attended home births were a heterogenous group. In addition to CNMs, the analysis included anyone else who would register as "midwife" on a birth certificate – a group that represents an extremely varied range of skill.

These attendants could be could have been CNMs, certified midwives, certified professional midwives, licensed midwives, or lay midwives. CNMs must have a bachelor’s degree as a registered nurse and then graduate from an accredited school of nurse-midwifery. A certified midwife is a graduate of the same school of midwifery program, but can hold a degree in a field other than nursing. The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) regulates these providers.

No college degree is required for a certified professional midwife. They can obtain licensure based on an apprenticeship portfolio or from other schools of midwifery. The Midwives Alliance of North America and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives regulate this group. Lay midwives are allowed to practice in some states, but there is no regulatory board, and no licensure or educational requirements.

In all probability, very few CNMs attended the home births in Dr. Grunebaum’s study, according to Jesse Bushman, ACNM’s director of advocacy and government affairs. The college’s own data indicate that 90% of deliveries performed by members are in hospitals. Only 30% of home births recorded in the CDC data were performed by CNMs, he said.

"That is one issue we have with Dr. Grunebaum’s results," Mr. Bushman* said in an interview. "There are many people who could call themselves a midwife who may not have the training or competencies that CNMs do. To lump them together is quite problematic."

In an interview, Dr. Grunebaum said that he had parsed out the mortality results by specific provider group. However, he would not release those numbers, saying it could jeopardize his study’s peer-reviewed publication. "I will tell you that CNMs at home did much, much worse than CNMs in the hospital, and that other midwives at home were not far behind."

Birth outcomes data just released by the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) align with Dr. Grunebaum’s numbers (J. Midwifery Womens Health 2014 Jan. 30 [doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12172]). But the interpretation – if not the numbers – lies in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Grunebaum said the study illustrates the danger of home birth. MANA hailed it as proof of home birth’s safety.

"The results of this study ... confirm the safety and overwhelmingly positive health benefits for low-risk mothers and babies who choose to birth at home with a midwife," the group noted on its website. "At every step of the way, midwives are providing excellent care. This study enables families, providers, and policy makers to have a transparent look at the risks and benefits of planned home birth, as well as the health benefits of normal physiologic birth."

The study was a voluntary survey that examined data from almost 17,000 home births. The voluntary nature troubles Dr. Grunebaum, who pointed out that midwives with poor outcomes probably would not have submitted data.

There was an 11% hospital transfer rate in the cohort from the midwives study. There were 43 fetal deaths in the intrapartum, early, and late neonatal periods; 8 of these were from lethal congenital defects. The remaining deaths translated to a total neonatal mortality rate of 1.3/1,000.

Twenty-two died during labor, but before birth. For 13, the causes were known: placental abruption (2), intrauterine infection (2), cord accidents (3), complications of maternal gestational diabetes (2), meconium aspiration (1), shoulder dystocia (1), complications of preeclampsia (1), and liver rupture and hypoxia (1).

Seven babies died during the first 6 days of life. The causes were secondary to cord accidents (2, one with shoulder dystocia), and hypoxia or ischemia of unknown origin (5).

Six infants died in the late neonatal period. Two deaths were secondary to cord accidents, and four were from unknown causes.

Of 222 breech births, three infants died (13/1,000). Of 3,773 births to primiparous women, 11 infants died (2.9/1,000). Of 1,052 attempted vaginal births, 3 infants died (2.85/1,000)

"These numbers are horrible," Dr. Grunebaum said. "There is no longer room for the argument from home birth supporters that while the risk may be increased, it’s still very low in terms of absolute risk."

"This view has even been expressed by our own specialists," he added, referring to an American Academy of Pediatrics position paper on planned home birth (Pediatrics 2013;131:1016-20). While maintaining that birth is safest in a hospital or birthing center, the paper acknowledges that the two- or threefold overall increase in mortality associated with home birth is low – generally translating to about 1 in 1,000 newborns.

"That minimizes the extra risk involved in home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "We should have no acceptance for any increase in death or injury in exchange for parental convenience or for fewer interventions. We need to disclose these increased risks to mothers, and perform direct counseling against home birth."

His study fans a long-simmering debate about the best places to birth. Proponents of both philosophies want the same primary outcome: healthy mothers and infants. The debate? How to best get there.

Midwife-assisted home birth has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to CDC data, there were about 16,000 in 2007; by 2012, it was about 23,500. The rise is mostly seen in a very specific demographic – well-educated, financially secure white women with at least one other child who was, most frequently, born in a hospital.

Dr. Grunebaum attributed the rise to some women’s desire to avoid what they perceive as intrusive labor and birth management. With this thought, at least, others do agree.

Eugene DeClercq, Ph.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and of public health at Boston University, has worked on three national surveys that poll new mothers about their experiences with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and postpartum life.

Childbirth Connection (childbirthconnection.org) conducted the Listening to Mothers surveys in 2002, 2006, and 2012. The survey reports are intended to serve as policy resources for improving the childbearing experience for women and their families.

"One of the real questions we need to look at is, what’s going on in hospitals that makes women consider giving birth outside the hospital," Dr. DeClercq said in an interview. "What has come through in our interviews is that many women are quite fine with the ways things go in a hospital. They are for any intervention that they think will make a safer birth. But many women are not. They report feeling pressured to have interventions, and worried that one will lead to another and another, in a cascade that can eventually end up in a cesarean section."

This is a legitimate concern in the United States, he said – a country in which the cesarean rate hovers around 30%, and ranges from 7% to 70% across hospitals. "If you lived ... where there was a 70% rate of cesarean – 70%! – might you be thinking about some way to avoid that?"

In the Listening to Mothers II survey, women were asked a series of questions about their experiences with labor and delivery. The results of the survey revealed that 47% of first-time mothers were induced. "Of those having an induction, 78% had an epidural, and of those mothers who had both an attempted induction and an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 31%," the report noted. "Those who experienced either labor induction or an epidural, but not both, had cesarean rates of 19% to 20%. For those first-time mothers who experienced neither attempted induction nor an epidural, the unplanned cesarean rate was 5%."

Like it or not, he said, some women will go to almost any length to avoid interventions they fear may harm them and their babies.

The Listening to Mothers survey found that a quarter of women who had given birth in a hospital would consider a home birth. Most women in the survey (2/3) said a woman should be able to have a home birth if she wanted, and 11% said they would definitely want a home birth.

"If you look at the profile of home-birthers, it’s not like they are some crazy fringe group," Dr. DeClercq said. "These are very well-educated women, 75% of whom have already had a hospital birth. They are researching and weighing the pros and cons. They’re not just making some random decision."

His data also suggest that women who transfer to a hospital from a home birth fear judgment and even recrimination. "The consequences of that can be a delay in transfer when it’s necessary, and can lead to problems," even poor infant outcomes.

On this point at least, the two sides find common ground.

"Most of us will never attend a home birth," Dr. Grunebaum said. "But we will encounter patients asking us about home births and seeking hospital transfer for successful or complicated home births, and babies transferred after a home birth. And for these we need to provide compassionate, nonjudgmental care."

None of the sources interviewed for this story reported any financial disclosures.

*Correction, 3/4/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated Mr. Bushman's name.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Major finding: Total neonatal mortality in midwife-assisted hospital births was 0.32/1,000. For a midwife-attended home birth, that number was 1.26/1,000 – almost a fourfold increase in relative risk.

Data source: A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention database study that looked at 14 million births from 2006 to 2009.

Disclosures: None of the sources interviewed for this story reported any financial disclosures.