User login

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

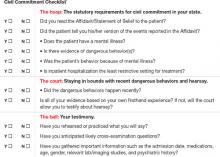

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Testifying in civil commitment proceedings sometimes is the only way to make sure dangerous patients get the hospital care they need. But for many psychiatrists, providing courtroom testimony can be a nerve-wracking experience because they:

- lack formal training about how to testify

- lack familiarity with laws and court procedures

- fear cross-examination.

Training programs are required to teach psychiatry residents about civil commitment but not about how to testify.1,2 Residents who get to take the stand during training usually do not receive any instruction.2 Knowing some fundamentals of testifying can reduce your anxiety and reluctance to take the stand3 and help you to perform better in court.

Court procedures

A doctor may not force a patient to stay in a hospital, no matter how much the patient needs treatment. Only courts have legal authority to order involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and courts may do this only after receiving proof that civil commitment is legally justified. Statutory criteria for civil commitment vary across jurisdictions, but typically, the court must hear evidence proving that a person:

- exhibits clear signs of a mental illness

- and because of the mental illness recently did something that placed himself or others in physical danger.

Courts usually rely on testimony from patients’ caregivers for this evidence. Thus, testifying is a skill psychiatrists must exercise to care for seriously ill patients who need treatment but don’t want it.

Testifying and playing basketball have a lot in common. To score points in basketball, a player must put the ball through the hoop and stay in bounds.

To be effective in a civil commitment hearing, a psychiatrist needs a similar game plan. The ball is your testimony, the hoop is the law’s exact wording in your state, and the bounds are recent dangerous behavior.

Completing the Civil Commitment Checklist ( Figure ) will help you determine if you are ready to go to court. Download a PDF of this checklist and a worksheet to compile information you will need to provide accurate and relevant testimony.

Figure: Are you ready to testify in a civil commitment hearing?

*If you answer “yes” to all questions, you are ready to testify about the need for civil commitment. If you answer “no” to any bulleted items, civil commitment may be inappropriate. If you answer “no” to any of the other questions, you’re not ready to go to court

Shoot the ball through the hoop

As early as the mid-19th century, attorneys and physicians realized that “no physician or surgeon could be a satisfactory expert witness without some knowledge of the law.”4 You may have the best basketball shooting technique in the world, but it won’t help if you don’t know where the hoop is. Likewise, you’ll be shooting blind if you come to court without knowing your state’s requirements for civil commitment—which many psychiatrists don’t know.5

Your skills at diagnosis and verbal persuasiveness are critical to good testimony, but if you don’t directly address the requirements for involuntary hospitalization in your state, your testimony may be irrelevant. A court cannot authorize civil commitment unless your testimony clearly and convincingly shows that a patient is mentally ill and dangerous—as defined by the law in your state.

In most states, you can look up your state’s commitment statute on the Internet, and you can take a printed copy of the statute to the witness stand if you wish. Using the law’s actual wording, you can give the court examples of behavior that show why your patient needs hospitalization.

For example, Ohio law defines a “mental disorder” for purposes of involuntary hospitalization as “a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life.”6 In Ohio and many other states, an official psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient for civil commitment. Of course, psychiatrists should formulate diagnostic opinions using well-established criteria. But in court, the diagnosis is like the backboard—it is not the hoop that the ball must pass through. The court needs to know whether a patient’s recent actions are manifestations of impairments listed in the statute.

Here’s an example of testimony that makes the basketball hit the backboard but doesn’t put the ball through the hoop:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type, which he’s had for quite a number of years. Patients with paranoid schizophrenia have a hard time because they think people are after them. Based on my experience, I don’t see how my patient can survive outside the hospital right now. He’s too paranoid, and his thinking is messed up.”

Though this testimony may be medically sound, the psychiatrist has not told the court specifically how the patient’s illness impairs his present functioning. Here’s an example of a ball going through the hoop after bouncing off the backboard:

Doctor: “Your honor, my patient has schizophrenia, paranoid type. He hears voices saying that the government is trying to assassinate him by poisoning his food and medications. As a result, he stopped taking medications 5 days ago and left the safety of his group home. He has been living under an overpass and refusing to eat. He has become malnourished and dehydrated. This shows he has a substantial disorder of thought and judgment that keeps him from recognizing reality and meeting the ordinary demands of life.”

Staying in bounds

As a witness, your role is to tell the court the truth about your patient’s situation so that justice can be served—if necessary, by allowing the state to override your patient’s liberty interests through involuntary hospitalization.7 To justify involuntary hospitalization in most states, the court must find that your patient is both mentally ill and has recently done something dangerous.

In basketball, the referee stops the game when the ball goes out of bounds. Similarly, the court may stop you if your testimony goes out of bounds by invoking non-recent evidence to demonstrate current dangerousness. For example:

Doctor: “Your honor, this patient has been hospitalized twice in the last 10 months after intentionally overdosing on medications. He told me that last month he tried to kill himself with pills. I know this patient well, and I fear he’s going to overdose again.”

Patient’s attorney: “Objection, your honor. What my client said 1 month ago has nothing to do with his alleged dangerousness today.”

The judge may sustain the objection and disregard your testimony because the events you have recounted fall outside your jurisdiction’s time frame for a “recent” event. What your patient said last month may well make you think your patient is at risk now, but the law establishes sometimes-arbitrary boundaries to protect patients’ liberty. The legal justification is that placing time limits on dangerous behavior minimizes the risk of an erroneous civil commitment; evidence of actual, recent behavior increases the likelihood of real, current danger and reduces the risk of involuntarily hospitalizing someone who would not do harm.8

The definition of “recent” varies from state to state. Pennsylvania looks at behavior within the last 30 days;9 Utah uses 7 days.10 Often, the law is not clear; rather than set firm time restrictions, some states consider whether the actions in question are “material and relevant to the person’s present condition.”11

Know what your jurisdiction considers “recent” behavior. If your state’s statute is not clear, ask a judge or attorney. As you think about your testimony, make sure that information describes dangerous behavior within the time frame that the court will accept as “recent.”

Cross-examination

Civil commitment hearings are supposed to be adversarial. The “proponent” of involuntary hospitalization (the State) puts on its best case, hoping to convince the judge (or occasionally, a jury) that commitment is justified. The “respondent” (the patient facing potential commitment) has many of the rights that criminal defendants have, including the right to an attorney and the right to challenge witnesses—including psychiatrists—through cross-examination.12

Psychiatrists aren’t accustomed to having their clinical reasoning forcefully challenged. When they disagree, psychiatrists usually seek to persuade each other and reach consensus rather than openly criticize colleagues and point out flaws in their opinions about patients. Even when insurance companies and patients disagree with you, they usually don’t try to discredit you.

Testifying is different.13 Expect to have your conclusions bluntly challenged in civil commitment hearings. But remember: as in a basketball game, attorneys’ cross-examination challenges are not personal—they’re intended only to win the game. Also, you can practice. Just as practicing against opponents improves skills needed to win basketball games, practicing against real or anticipated cross-examination can help you respond when you’re testifying. Be prepared to answer commonly asked questions ( Table 1 ), such as:

“Doctor, you’ve testified that Mr. Jones has bipolar disorder. Aren’t all psychiatric diagnoses just a guess?”

“Doctor, how can you be certain that Mr. Smith’s psychosis, as you call it, was the result of schizophrenia, not alcohol intoxication?”

“Well, doctor, if you’re saying that Mrs. Clark’s psychosis was caused by a urinary tract infection, isn’t that a medical problem and not a psychiatric problem that we can lock her up for?”

Other ways to prepare:

- Have a colleague play the part of an opposing attorney who is trying to find fault with your clinical reasoning.

- Imagine you are retained by an attorney who wants to find holes in your own testimony.

- Watch other psychiatrists testify, and learn from their triumphs or mistakes.

Table 1

Questions you’re likely to face when testifying

| Question | Importance |

|---|---|

| What is your diagnosis? | In all states, a mental illness leading to dangerous behavior is required for involuntary hospitalization. Courts are less interested in the name of the disorder than in knowing how its symptoms affect the respondent and lead to danger |

| Why is the hospital the least restrictive environment? | The “least restrictive” legal standard14 is a safeguard against unwarranted hospitalization. Be ready to explain why other treatment options (outpatient, day hospitals, etc.) are not appropriate |

| What medications is the patient taking? | Be prepared to tell the court whether the patient was taking medications before and since admission. Know which medications are being prescribed for the patient in the hospital |

| Why does your diagnosis differ from the diagnosis of another clinician in the chart? | Cross-examining attorneys will often try to discredit your opinion by pointing out that other clinicians diagnosed something different. You can explain that different disorders belong within common diagnostic categories (for example, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are both psychoses). Explaining your answer this way enhances its credibility by demonstrating agreement with the other clinician |

| What is the patient’s response to the allegations of dangerousness listed in the chart? | Don’t neglect patients’ views. Their answers allow you to testify about the patient from direct knowledge and often provide evidence of thought, mood, or judgment problems |

Good and bad shots

Good basketball players avoid fouls and taking shots that opponents can block easily. A good psychiatric witness knows how to avoid committing legal fouls and having testimony blocked.

The hearsay block. In clinical practice, psychiatrists should use and often rely on information about their patients that they obtain from other persons. But in court, testifying about such information could be disallowed on grounds that it is hearsay—testimony about what someone else saw or heard.

In civil commitment hearings, rules against allowing hearsay protect patients from accusations that may be false or misleading and that they cannot challenge through cross-examination. Although many states have a “hearsay exception” for civil commitment hearings—meaning that doctors may testify about what others have told them—not all do. If you practice in a state without this exception, you’ll need to gather information and plan your testimony carefully to avoid having the basis for your opinion excluded.

To avoid this “block,” testify only about events you saw or heard. To be fair to patients, always ask them about their side of the story. You can then testify about your clinical findings—what you saw and heard—instead of what someone else said. For example:

Doctor: “Your wife told me you wanted to kill yourself. Is that true?”

Patient: “It wasn’t my wife. I told my brother I wanted to kill myself.”

Doctor: “How about now? Do you still want to kill yourself?”

Patient: “Yes, I do.”

The doctor now can testify about first-hand experience with the patient:

Doctor: “Your honor, I asked the patient whether he told anyone that he wanted to kill himself. He told me he had told his brother he wanted to kill himself, and that he still felt that way.”

Play only your position

Basketball teams get into trouble if players try to do things others are supposed to do. Players are not supposed to give orders to the coach. In court, your role is to provide expert testimony about your patient and psychiatry. Stay in that role:

- Don’t address the ultimate legal question, as in saying, “My patient meets this state’s commitment criteria.” That’s for the judge to decide.

- Don’t opine about the moral virtues or shortcomings of the courts or hearings: “My patient desperately needs treatment, but you’re just asking about whether he fits narrow legal rules.”

- Don’t testify about topics on which you’re not an expert: “I think the police used too much force when they handcuffed my patient.”

Table 2

Dos and don’ts of testifying in a civil commitment hearing

| Do… | Don’t… |

|---|---|

| Wear conservative business attire, which shows that you take your work seriously | Dress casually. Though casual dress is OK in many workplaces, lawyers wear suits in court |

| Remain calm, professional, and respectful | Make jokes or sarcastic remarks; a cross-examining attorney will easily discredit you by pointing out that this is a ‘serious matter’ |

| Use recent examples of the patient’s dangerousness | Testify about your patient’s childhood or remote events |

| Describe behaviors or statements you witnessed or obtained from the patient | Testify about information obtained only from other people |

| Pause before answering each question. Doing this allows time for you to think and for an attorney to object to the question | Lose your cool or argue with the attorneys or judge |

| Source: Adapted from Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2007;7(3):25-40 | |

Related resources

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).

1. Barr NI, Suarez JM. The teaching of forensic psychiatry in law schools, medical schools and psychiatric residencies in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(6):612-616.

2. Lewis CF. Teaching forensic psychiatry to general psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):40-46.

3. Sata LS, Goldenberg EE. A study of involuntary patients in Seattle. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1977;28(11):834-837.

4. Curran WJ. Titles in the medicolegal field: a proposal for reform. Am J Law Med. 1975;1:1-11.

5. Brooks RA. Psychiatrist’s opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:219-228.

6. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01(A).

7. Rotter M, Preven D. Commentary: general residency training—the first forensic stage. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:324-327.

8. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:337.

9. 50 PS § 7301(b).

10. Utah Code Ann § 62A-15-631(a).

11. Matter of D.D., 920 P2d 973, 975 (Mont 1996).

12. Perlin ML. Mental disability law—civil and criminal. 2nd ed, vol. 1, § 2B-3.1. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing; 1998.

13. Gutheil T. The psychiatrist as expert witness. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1998:11–18.

14. Lake v Cameron, 364 F2d 657 (DC Cir 1967).