User login

TRANSVAGINAL MESH FOR POP: NEW AND

NOTEWORTHY RESOURCES

• Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: Overview, registry resources, FAQs, more

• Vaginal mesh manufacturer closing due to lawsuit concerns, Wall Street Journal, 2/29/16

Approximately 300,000 surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are performed annually in the United States. In 2006, the peak of synthetic mesh use for prolapse surgery, one-third of all prolapse operations involved some mesh use.1,2 The use of vaginal mesh has declined since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued warnings in 2008 and 2011.

Historically, the use of mesh for gynecologic surgery began in the 1970s, with abdominal POP repair.3 Transvaginal mesh use for POP surgeries became FDA-cleared in 2004. The first cleared mesh device was classified as class II (moderate risk).3 Subsequent mesh devices were given 510(k) clearance, which bypasses clinical trials and requires manufacturers only to show that their product is substantially equivalent to one already on the market.4 More than 40 companies began the manufacturing of mesh devices in the 10 years following the initial cleared device.3

Of course, much controversy has surrounded mesh use in recent years, with common adverse events reported, including severe pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, infection, bleeding, organ perforation, and problems from mesh eroding into surrounding tissues.3 The FDA very recently (in January 2016) reclassified this device from moderate risk to high risk (class III), after indicating in May 2014 that such action was necessary. (See “Timeline of FDA’s actions regarding surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse” on page 46.) This reclassification requires a premarket approval application to be filed for each device, with safety and efficacy demonstrated. There are approximately 5 companies currently manufacturing mesh for transvaginal POP repair.3

OBG Management recently sat down with Cheryl Iglesia, MD, director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and professor in the Departments of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Urology at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC. Dr. Iglesia serves, from 2011 through 2017, as a member on the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel, and she addressed lessons learned over the past decade on synthetic and biologic mesh at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in Las Vegas, Nevada, this past December.

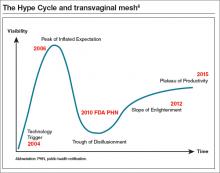

In this Q&A article, she addresses the current state of transvaginal mesh use and how it relates to the innovation adaptation curve (otherwise known as the Hype Cycle), how new mesh types differ from older ones, and how the specialty can move into a future of POP surgery in which innovation and data will rule.

OBG Management: Where is transvaginal mesh use on the so-called “Hype Cycle,” or innovation adaptation curve?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: The Hype Cycle was developed and branded by the Gartner company, an information technology advisory and research firm. This cycle refers to the graphical depictions of how a technology or application will evolve over time. After all, new technologies may make bold promises, and the hype may not translate to commercial viability. Each cycle drills down into the key phases of a technology’s life cycle: the trigger, peak of inflated expectations, trough of disillusionment, slope of enlightenment, and plateau of productivity.5

If we use the Hype Cycle to drill down the phases of transvaginal mesh’s life cycle, we begin in 2004 with the FDA clearance of the first vaginal mesh system (FIGURE).6 The height of its use (the “peak of inflated expectation”) was around 2006, when essentially one-third of all annual surgeries performed for prolapse repair used some type of mesh placed either abdominally or transvaginally.2

Subsequently, adverse events began being reported to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. In 2008, the FDA published its first notification of serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh, with more than 1,000 reports from 9 surgical mesh manufacturers.7 A second alert followed in 2011.8 By this time, we had reached our “trough of disillusionment.”

In 2016, we have reached the “plateau of productivity” on the innovation adaptation curve. During this phase on the Hype Cycle the criteria for assessing the technology’s viability are clearly defined. I say we are in this phase because now we have a way of completing more postmarket surveillance on mesh devices. We now can see what applying the technology is like in the real world, generalized across many different surgeons’ hands, and we have a way of performing comparative studies with native tissue.

OBG Management: How do the new types of mesh differ from those that have been removed from the market?

Dr. Iglesia: In January 2012, there were about 40 types of surgical mesh available from more than 30 manufacturers of transvaginal mesh. At that time, the FDA imposed 522 orders on these companies, requiring them to provide up to 3 years of postmarket data on the safety and effectiveness of their devices.9 Some companies ceased production, including Johnson and Johnson and CR Bard. Today, there are about a half-dozen mesh types on the market, and these are undergoing evaluation.

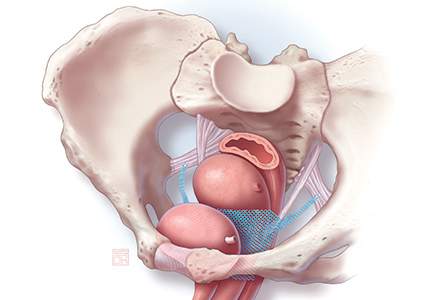

First-generation meshes were the size of a sheet of paper; now, meshes can fit on the palm of your hand. They also do not have the legs or the arms that are placed using trocars through the transobturator or ischioanal fossae, which can approach nearby nerves, arteries, or other vital structures. They are significantly lighter weight, and some have color to make the native tissue and mesh interface more apparent.

Mesh contraction,10 inflammation of the mesh involving surrounding soft tissue,11 and stress shearing at the mesh/soft tissue interface12 have been implicated as potential causes of pain with synthetic mesh. The most commonly available synthetic mesh today is type 1 polypropylene (macroporous monofilament), with a large pore size (usually greater than 75 microns).

Non−cross linked biologic grafts also are available currently, with several cross-linked grafts removed from the market by 2013 because their design was associated with graft stiffness and shrinkage, which had the potential to distort the pelvic anatomy.

Non−cross linked biologic grafts may be associated with fewer mesh-related complications compared with synthetic mesh, but there are limited data on their use in POP repair and there are many unanswered questions. The current concerns with biologics are their tensile properties, foreign body reactions, and documented autolysis. Modifications to them may affect their soft tissue reactivity, but outcomes depend on the technique used for implantation.

OBG Management: When do you consider vaginal mesh use for prolapse?

Dr. Iglesia: A recent Cochrane review shows that some data favor mesh for decreased recurrence, but there are trade-offs.13 I consider mesh use in the setting of recurrent prolapse, especially anterior, for advanced-stageprolapse, and under certain situations, including when there is a known collagen deficiency and there are contraindications to abdominal surgery. However, pelvic pain always is a concern, and surgeons should be extremely careful when choosing to use mesh in patients with known chronic pelvic pain.

The FDA recommends that clinicians treating patients with POP recognize that POP can be treated successfully without mesh and that this native tissue repair will avoid completely the risk of mesh-related complications (TABLE 1).14 Patients should be made aware of alternatives to vaginal mesh when deciding on surgical repair, including nonsurgical options, native tissue repair, and abdominally (laparoscopic, robotic, or open) placed sacrocolpopexy mesh.

OBG Management: How does the Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry solve issues that existed prior to the mesh controversy?

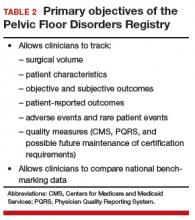

Dr. Iglesia: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry (PFDR), which can be accessed online (http://www.pfdr.org), is a private and public collaboration including many medical societies: the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Urologic Association, the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, and industry. Its objectives are 3-fold15:

- to collect, store, and analyze clinical data related to POP treatment

- to establish common data elements and quality metrics

- to provide a framework for external stakeholders to conduct POP research (TABLE 2).

All involved PFDR partners, which also includes patient advocates, reached consensus on the outcomes that matter scientifically in terms of objective cure rates and complications as well as on subjective outcomes that matter most to patien

Quite frankly, subjective patient-reported outcomes probably trump any other outcome because, in general, patients are risk averse—which is to say that they are much more easily accepting of recurrence or failure than of a serious adverse event from a mesh-related complication. With the PFDR, we are able to capture not only that objective data but also the critically important patient-centered outcomes.16

With the PFDR, a patient who goes to surgeon B following a complication with surgeon A can still be followed. I look forward to the tracking capability within the registry and the many prospective comparative trials that can be conducted.

Unfortunately, differences between older and newer transvaginal mesh delivery systems will not be evaluated as part of the required 522 studies within the PFDR; however, I really look forward to seeing the data roll out on the second generation vaginal mesh kits compared to native tissue repai

The PFDR has 2 options for volunteer registry participation, the PFDR-Quality Improvement and PFDR-Research. I encourage specialists who are board-certified in Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery to be involved in the quality improvement research. For this, physicians basically can track their own success and complication rates, including nonsurgical outcomes. This information could be helpful to achieving our ongoing goal of getting better at what we do surgically. If you are doing well, it will be very validating. Your patients will be happy, you will have good outcomes, and that probably will not be bad for marketing your practice.

There may be some opportunities to reach the health-related quality indicators that we need to meet right now as part of government-mandated initiatives. For many reasons, it is important for surgeons who are performing a high volume of POP surgeries per year to get involved in the PFDR. In fact, even if you are not performing surgery, you still can get involved with the nonsurgical pessary side. This also is important information for us to move forward with as a specialty as we seek to understand the natural history of POP.

The PFDR will serve many different purposes—one of the best of which is that we are going to be able to safely promote mesh technology for the most appropriate cases and not stifle innovation. The comparison groups, already built in to the registry, will allow for native tissue arms to be compared head to head with the currently available meshes. In addition, we will be able to see signals sooner if certain products or patient profiles, and even individual surgeon outcomes, are concerning.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, was the Keynote Speaker at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium held in Las Vegas, Nevada, December 10–12, 2015. This article was developed from Dr. Iglesia's presentation titled "The How, Why and Where of Synthetic and Biologic Mesh: Lessons Learned."

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Urogynecologic surgical mesh: Update on the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal placement for pelvic organ prolapse. Washington DC: US Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Devices and Radiological Health; July 2011.

- Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS, et al. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000 to 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1105–1115.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm479732.htm. Updated January 6, 2016. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Premarket notification 510(k). US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/PremarketSubmissions/PremarketNotification510k/default.htm. Updated September, 16, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2016.

- Gartner Hype Cycle. Gartner website. http://www.gartner.com/technology/research/methodologies/hype-cycle.jsp. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Barber MD. Thirty-third American Urogynecologic Society Annual Meeting Presidential Address: the end of the beginning. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(1):2−7.

- FDA public health notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Updated August 6, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm. Updated October 6, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Hughes C. FDA issues 522 orders for postmarket surveillance studies: urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. American Urogynecologic Society website. . Published January 5, 2012. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):325–330.

- Ozkan N, Kayaoglu HA, Ersoy OF, Celik A, Kurt GS, Arabaci E. Effects of two different meshes used in hernia repair on nerve transport. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(5):670–675.

- Clemons JL, Weinstein M, Guess MK, et al; AUGS Research Committee. Impact of the 2011 FDA transvaginal mesh safety update on AUGS members’ use of synthetic mesh and biologic grafts in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(4):191–198.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cocrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2;CD012079.

- Information for Health Care Providers for POP. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/implantsandprosthetics/urogynsurgicalmesh/ucm345204.htm. Updated January 4, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2016.

- Bradley CS, Visco AG, Weber LeBrun EE, Barber MD. The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: purpose and development [published online ahead of print January 30, 2016]. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncementsFeiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management.

TRANSVAGINAL MESH FOR POP: NEW AND

NOTEWORTHY RESOURCES

• Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: Overview, registry resources, FAQs, more

• Vaginal mesh manufacturer closing due to lawsuit concerns, Wall Street Journal, 2/29/16

Approximately 300,000 surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are performed annually in the United States. In 2006, the peak of synthetic mesh use for prolapse surgery, one-third of all prolapse operations involved some mesh use.1,2 The use of vaginal mesh has declined since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued warnings in 2008 and 2011.

Historically, the use of mesh for gynecologic surgery began in the 1970s, with abdominal POP repair.3 Transvaginal mesh use for POP surgeries became FDA-cleared in 2004. The first cleared mesh device was classified as class II (moderate risk).3 Subsequent mesh devices were given 510(k) clearance, which bypasses clinical trials and requires manufacturers only to show that their product is substantially equivalent to one already on the market.4 More than 40 companies began the manufacturing of mesh devices in the 10 years following the initial cleared device.3

Of course, much controversy has surrounded mesh use in recent years, with common adverse events reported, including severe pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, infection, bleeding, organ perforation, and problems from mesh eroding into surrounding tissues.3 The FDA very recently (in January 2016) reclassified this device from moderate risk to high risk (class III), after indicating in May 2014 that such action was necessary. (See “Timeline of FDA’s actions regarding surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse” on page 46.) This reclassification requires a premarket approval application to be filed for each device, with safety and efficacy demonstrated. There are approximately 5 companies currently manufacturing mesh for transvaginal POP repair.3

OBG Management recently sat down with Cheryl Iglesia, MD, director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and professor in the Departments of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Urology at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC. Dr. Iglesia serves, from 2011 through 2017, as a member on the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel, and she addressed lessons learned over the past decade on synthetic and biologic mesh at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in Las Vegas, Nevada, this past December.

In this Q&A article, she addresses the current state of transvaginal mesh use and how it relates to the innovation adaptation curve (otherwise known as the Hype Cycle), how new mesh types differ from older ones, and how the specialty can move into a future of POP surgery in which innovation and data will rule.

OBG Management: Where is transvaginal mesh use on the so-called “Hype Cycle,” or innovation adaptation curve?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: The Hype Cycle was developed and branded by the Gartner company, an information technology advisory and research firm. This cycle refers to the graphical depictions of how a technology or application will evolve over time. After all, new technologies may make bold promises, and the hype may not translate to commercial viability. Each cycle drills down into the key phases of a technology’s life cycle: the trigger, peak of inflated expectations, trough of disillusionment, slope of enlightenment, and plateau of productivity.5

If we use the Hype Cycle to drill down the phases of transvaginal mesh’s life cycle, we begin in 2004 with the FDA clearance of the first vaginal mesh system (FIGURE).6 The height of its use (the “peak of inflated expectation”) was around 2006, when essentially one-third of all annual surgeries performed for prolapse repair used some type of mesh placed either abdominally or transvaginally.2

Subsequently, adverse events began being reported to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. In 2008, the FDA published its first notification of serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh, with more than 1,000 reports from 9 surgical mesh manufacturers.7 A second alert followed in 2011.8 By this time, we had reached our “trough of disillusionment.”

In 2016, we have reached the “plateau of productivity” on the innovation adaptation curve. During this phase on the Hype Cycle the criteria for assessing the technology’s viability are clearly defined. I say we are in this phase because now we have a way of completing more postmarket surveillance on mesh devices. We now can see what applying the technology is like in the real world, generalized across many different surgeons’ hands, and we have a way of performing comparative studies with native tissue.

OBG Management: How do the new types of mesh differ from those that have been removed from the market?

Dr. Iglesia: In January 2012, there were about 40 types of surgical mesh available from more than 30 manufacturers of transvaginal mesh. At that time, the FDA imposed 522 orders on these companies, requiring them to provide up to 3 years of postmarket data on the safety and effectiveness of their devices.9 Some companies ceased production, including Johnson and Johnson and CR Bard. Today, there are about a half-dozen mesh types on the market, and these are undergoing evaluation.

First-generation meshes were the size of a sheet of paper; now, meshes can fit on the palm of your hand. They also do not have the legs or the arms that are placed using trocars through the transobturator or ischioanal fossae, which can approach nearby nerves, arteries, or other vital structures. They are significantly lighter weight, and some have color to make the native tissue and mesh interface more apparent.

Mesh contraction,10 inflammation of the mesh involving surrounding soft tissue,11 and stress shearing at the mesh/soft tissue interface12 have been implicated as potential causes of pain with synthetic mesh. The most commonly available synthetic mesh today is type 1 polypropylene (macroporous monofilament), with a large pore size (usually greater than 75 microns).

Non−cross linked biologic grafts also are available currently, with several cross-linked grafts removed from the market by 2013 because their design was associated with graft stiffness and shrinkage, which had the potential to distort the pelvic anatomy.

Non−cross linked biologic grafts may be associated with fewer mesh-related complications compared with synthetic mesh, but there are limited data on their use in POP repair and there are many unanswered questions. The current concerns with biologics are their tensile properties, foreign body reactions, and documented autolysis. Modifications to them may affect their soft tissue reactivity, but outcomes depend on the technique used for implantation.

OBG Management: When do you consider vaginal mesh use for prolapse?

Dr. Iglesia: A recent Cochrane review shows that some data favor mesh for decreased recurrence, but there are trade-offs.13 I consider mesh use in the setting of recurrent prolapse, especially anterior, for advanced-stageprolapse, and under certain situations, including when there is a known collagen deficiency and there are contraindications to abdominal surgery. However, pelvic pain always is a concern, and surgeons should be extremely careful when choosing to use mesh in patients with known chronic pelvic pain.

The FDA recommends that clinicians treating patients with POP recognize that POP can be treated successfully without mesh and that this native tissue repair will avoid completely the risk of mesh-related complications (TABLE 1).14 Patients should be made aware of alternatives to vaginal mesh when deciding on surgical repair, including nonsurgical options, native tissue repair, and abdominally (laparoscopic, robotic, or open) placed sacrocolpopexy mesh.

OBG Management: How does the Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry solve issues that existed prior to the mesh controversy?

Dr. Iglesia: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry (PFDR), which can be accessed online (http://www.pfdr.org), is a private and public collaboration including many medical societies: the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Urologic Association, the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, and industry. Its objectives are 3-fold15:

- to collect, store, and analyze clinical data related to POP treatment

- to establish common data elements and quality metrics

- to provide a framework for external stakeholders to conduct POP research (TABLE 2).

All involved PFDR partners, which also includes patient advocates, reached consensus on the outcomes that matter scientifically in terms of objective cure rates and complications as well as on subjective outcomes that matter most to patien

Quite frankly, subjective patient-reported outcomes probably trump any other outcome because, in general, patients are risk averse—which is to say that they are much more easily accepting of recurrence or failure than of a serious adverse event from a mesh-related complication. With the PFDR, we are able to capture not only that objective data but also the critically important patient-centered outcomes.16

With the PFDR, a patient who goes to surgeon B following a complication with surgeon A can still be followed. I look forward to the tracking capability within the registry and the many prospective comparative trials that can be conducted.

Unfortunately, differences between older and newer transvaginal mesh delivery systems will not be evaluated as part of the required 522 studies within the PFDR; however, I really look forward to seeing the data roll out on the second generation vaginal mesh kits compared to native tissue repai

The PFDR has 2 options for volunteer registry participation, the PFDR-Quality Improvement and PFDR-Research. I encourage specialists who are board-certified in Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery to be involved in the quality improvement research. For this, physicians basically can track their own success and complication rates, including nonsurgical outcomes. This information could be helpful to achieving our ongoing goal of getting better at what we do surgically. If you are doing well, it will be very validating. Your patients will be happy, you will have good outcomes, and that probably will not be bad for marketing your practice.

There may be some opportunities to reach the health-related quality indicators that we need to meet right now as part of government-mandated initiatives. For many reasons, it is important for surgeons who are performing a high volume of POP surgeries per year to get involved in the PFDR. In fact, even if you are not performing surgery, you still can get involved with the nonsurgical pessary side. This also is important information for us to move forward with as a specialty as we seek to understand the natural history of POP.

The PFDR will serve many different purposes—one of the best of which is that we are going to be able to safely promote mesh technology for the most appropriate cases and not stifle innovation. The comparison groups, already built in to the registry, will allow for native tissue arms to be compared head to head with the currently available meshes. In addition, we will be able to see signals sooner if certain products or patient profiles, and even individual surgeon outcomes, are concerning.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, was the Keynote Speaker at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium held in Las Vegas, Nevada, December 10–12, 2015. This article was developed from Dr. Iglesia's presentation titled "The How, Why and Where of Synthetic and Biologic Mesh: Lessons Learned."

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

TRANSVAGINAL MESH FOR POP: NEW AND

NOTEWORTHY RESOURCES

• Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: Overview, registry resources, FAQs, more

• Vaginal mesh manufacturer closing due to lawsuit concerns, Wall Street Journal, 2/29/16

Approximately 300,000 surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are performed annually in the United States. In 2006, the peak of synthetic mesh use for prolapse surgery, one-third of all prolapse operations involved some mesh use.1,2 The use of vaginal mesh has declined since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued warnings in 2008 and 2011.

Historically, the use of mesh for gynecologic surgery began in the 1970s, with abdominal POP repair.3 Transvaginal mesh use for POP surgeries became FDA-cleared in 2004. The first cleared mesh device was classified as class II (moderate risk).3 Subsequent mesh devices were given 510(k) clearance, which bypasses clinical trials and requires manufacturers only to show that their product is substantially equivalent to one already on the market.4 More than 40 companies began the manufacturing of mesh devices in the 10 years following the initial cleared device.3

Of course, much controversy has surrounded mesh use in recent years, with common adverse events reported, including severe pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, infection, bleeding, organ perforation, and problems from mesh eroding into surrounding tissues.3 The FDA very recently (in January 2016) reclassified this device from moderate risk to high risk (class III), after indicating in May 2014 that such action was necessary. (See “Timeline of FDA’s actions regarding surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse” on page 46.) This reclassification requires a premarket approval application to be filed for each device, with safety and efficacy demonstrated. There are approximately 5 companies currently manufacturing mesh for transvaginal POP repair.3

OBG Management recently sat down with Cheryl Iglesia, MD, director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and professor in the Departments of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Urology at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC. Dr. Iglesia serves, from 2011 through 2017, as a member on the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel, and she addressed lessons learned over the past decade on synthetic and biologic mesh at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in Las Vegas, Nevada, this past December.

In this Q&A article, she addresses the current state of transvaginal mesh use and how it relates to the innovation adaptation curve (otherwise known as the Hype Cycle), how new mesh types differ from older ones, and how the specialty can move into a future of POP surgery in which innovation and data will rule.

OBG Management: Where is transvaginal mesh use on the so-called “Hype Cycle,” or innovation adaptation curve?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: The Hype Cycle was developed and branded by the Gartner company, an information technology advisory and research firm. This cycle refers to the graphical depictions of how a technology or application will evolve over time. After all, new technologies may make bold promises, and the hype may not translate to commercial viability. Each cycle drills down into the key phases of a technology’s life cycle: the trigger, peak of inflated expectations, trough of disillusionment, slope of enlightenment, and plateau of productivity.5

If we use the Hype Cycle to drill down the phases of transvaginal mesh’s life cycle, we begin in 2004 with the FDA clearance of the first vaginal mesh system (FIGURE).6 The height of its use (the “peak of inflated expectation”) was around 2006, when essentially one-third of all annual surgeries performed for prolapse repair used some type of mesh placed either abdominally or transvaginally.2

Subsequently, adverse events began being reported to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. In 2008, the FDA published its first notification of serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh, with more than 1,000 reports from 9 surgical mesh manufacturers.7 A second alert followed in 2011.8 By this time, we had reached our “trough of disillusionment.”

In 2016, we have reached the “plateau of productivity” on the innovation adaptation curve. During this phase on the Hype Cycle the criteria for assessing the technology’s viability are clearly defined. I say we are in this phase because now we have a way of completing more postmarket surveillance on mesh devices. We now can see what applying the technology is like in the real world, generalized across many different surgeons’ hands, and we have a way of performing comparative studies with native tissue.

OBG Management: How do the new types of mesh differ from those that have been removed from the market?

Dr. Iglesia: In January 2012, there were about 40 types of surgical mesh available from more than 30 manufacturers of transvaginal mesh. At that time, the FDA imposed 522 orders on these companies, requiring them to provide up to 3 years of postmarket data on the safety and effectiveness of their devices.9 Some companies ceased production, including Johnson and Johnson and CR Bard. Today, there are about a half-dozen mesh types on the market, and these are undergoing evaluation.

First-generation meshes were the size of a sheet of paper; now, meshes can fit on the palm of your hand. They also do not have the legs or the arms that are placed using trocars through the transobturator or ischioanal fossae, which can approach nearby nerves, arteries, or other vital structures. They are significantly lighter weight, and some have color to make the native tissue and mesh interface more apparent.

Mesh contraction,10 inflammation of the mesh involving surrounding soft tissue,11 and stress shearing at the mesh/soft tissue interface12 have been implicated as potential causes of pain with synthetic mesh. The most commonly available synthetic mesh today is type 1 polypropylene (macroporous monofilament), with a large pore size (usually greater than 75 microns).

Non−cross linked biologic grafts also are available currently, with several cross-linked grafts removed from the market by 2013 because their design was associated with graft stiffness and shrinkage, which had the potential to distort the pelvic anatomy.

Non−cross linked biologic grafts may be associated with fewer mesh-related complications compared with synthetic mesh, but there are limited data on their use in POP repair and there are many unanswered questions. The current concerns with biologics are their tensile properties, foreign body reactions, and documented autolysis. Modifications to them may affect their soft tissue reactivity, but outcomes depend on the technique used for implantation.

OBG Management: When do you consider vaginal mesh use for prolapse?

Dr. Iglesia: A recent Cochrane review shows that some data favor mesh for decreased recurrence, but there are trade-offs.13 I consider mesh use in the setting of recurrent prolapse, especially anterior, for advanced-stageprolapse, and under certain situations, including when there is a known collagen deficiency and there are contraindications to abdominal surgery. However, pelvic pain always is a concern, and surgeons should be extremely careful when choosing to use mesh in patients with known chronic pelvic pain.

The FDA recommends that clinicians treating patients with POP recognize that POP can be treated successfully without mesh and that this native tissue repair will avoid completely the risk of mesh-related complications (TABLE 1).14 Patients should be made aware of alternatives to vaginal mesh when deciding on surgical repair, including nonsurgical options, native tissue repair, and abdominally (laparoscopic, robotic, or open) placed sacrocolpopexy mesh.

OBG Management: How does the Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry solve issues that existed prior to the mesh controversy?

Dr. Iglesia: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry (PFDR), which can be accessed online (http://www.pfdr.org), is a private and public collaboration including many medical societies: the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Urologic Association, the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, and industry. Its objectives are 3-fold15:

- to collect, store, and analyze clinical data related to POP treatment

- to establish common data elements and quality metrics

- to provide a framework for external stakeholders to conduct POP research (TABLE 2).

All involved PFDR partners, which also includes patient advocates, reached consensus on the outcomes that matter scientifically in terms of objective cure rates and complications as well as on subjective outcomes that matter most to patien

Quite frankly, subjective patient-reported outcomes probably trump any other outcome because, in general, patients are risk averse—which is to say that they are much more easily accepting of recurrence or failure than of a serious adverse event from a mesh-related complication. With the PFDR, we are able to capture not only that objective data but also the critically important patient-centered outcomes.16

With the PFDR, a patient who goes to surgeon B following a complication with surgeon A can still be followed. I look forward to the tracking capability within the registry and the many prospective comparative trials that can be conducted.

Unfortunately, differences between older and newer transvaginal mesh delivery systems will not be evaluated as part of the required 522 studies within the PFDR; however, I really look forward to seeing the data roll out on the second generation vaginal mesh kits compared to native tissue repai

The PFDR has 2 options for volunteer registry participation, the PFDR-Quality Improvement and PFDR-Research. I encourage specialists who are board-certified in Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery to be involved in the quality improvement research. For this, physicians basically can track their own success and complication rates, including nonsurgical outcomes. This information could be helpful to achieving our ongoing goal of getting better at what we do surgically. If you are doing well, it will be very validating. Your patients will be happy, you will have good outcomes, and that probably will not be bad for marketing your practice.

There may be some opportunities to reach the health-related quality indicators that we need to meet right now as part of government-mandated initiatives. For many reasons, it is important for surgeons who are performing a high volume of POP surgeries per year to get involved in the PFDR. In fact, even if you are not performing surgery, you still can get involved with the nonsurgical pessary side. This also is important information for us to move forward with as a specialty as we seek to understand the natural history of POP.

The PFDR will serve many different purposes—one of the best of which is that we are going to be able to safely promote mesh technology for the most appropriate cases and not stifle innovation. The comparison groups, already built in to the registry, will allow for native tissue arms to be compared head to head with the currently available meshes. In addition, we will be able to see signals sooner if certain products or patient profiles, and even individual surgeon outcomes, are concerning.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, was the Keynote Speaker at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium held in Las Vegas, Nevada, December 10–12, 2015. This article was developed from Dr. Iglesia's presentation titled "The How, Why and Where of Synthetic and Biologic Mesh: Lessons Learned."

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Urogynecologic surgical mesh: Update on the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal placement for pelvic organ prolapse. Washington DC: US Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Devices and Radiological Health; July 2011.

- Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS, et al. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000 to 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1105–1115.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm479732.htm. Updated January 6, 2016. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Premarket notification 510(k). US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/PremarketSubmissions/PremarketNotification510k/default.htm. Updated September, 16, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2016.

- Gartner Hype Cycle. Gartner website. http://www.gartner.com/technology/research/methodologies/hype-cycle.jsp. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Barber MD. Thirty-third American Urogynecologic Society Annual Meeting Presidential Address: the end of the beginning. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(1):2−7.

- FDA public health notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Updated August 6, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm. Updated October 6, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Hughes C. FDA issues 522 orders for postmarket surveillance studies: urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. American Urogynecologic Society website. . Published January 5, 2012. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):325–330.

- Ozkan N, Kayaoglu HA, Ersoy OF, Celik A, Kurt GS, Arabaci E. Effects of two different meshes used in hernia repair on nerve transport. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(5):670–675.

- Clemons JL, Weinstein M, Guess MK, et al; AUGS Research Committee. Impact of the 2011 FDA transvaginal mesh safety update on AUGS members’ use of synthetic mesh and biologic grafts in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(4):191–198.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cocrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2;CD012079.

- Information for Health Care Providers for POP. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/implantsandprosthetics/urogynsurgicalmesh/ucm345204.htm. Updated January 4, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2016.

- Bradley CS, Visco AG, Weber LeBrun EE, Barber MD. The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: purpose and development [published online ahead of print January 30, 2016]. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncementsFeiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management.

- Urogynecologic surgical mesh: Update on the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal placement for pelvic organ prolapse. Washington DC: US Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Devices and Radiological Health; July 2011.

- Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS, et al. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000 to 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1105–1115.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm479732.htm. Updated January 6, 2016. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Premarket notification 510(k). US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/HowtoMarketYourDevice/PremarketSubmissions/PremarketNotification510k/default.htm. Updated September, 16, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2016.

- Gartner Hype Cycle. Gartner website. http://www.gartner.com/technology/research/methodologies/hype-cycle.jsp. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Barber MD. Thirty-third American Urogynecologic Society Annual Meeting Presidential Address: the end of the beginning. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(1):2−7.

- FDA public health notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Updated August 6, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm. Updated October 6, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Hughes C. FDA issues 522 orders for postmarket surveillance studies: urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. American Urogynecologic Society website. . Published January 5, 2012. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):325–330.

- Ozkan N, Kayaoglu HA, Ersoy OF, Celik A, Kurt GS, Arabaci E. Effects of two different meshes used in hernia repair on nerve transport. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(5):670–675.

- Clemons JL, Weinstein M, Guess MK, et al; AUGS Research Committee. Impact of the 2011 FDA transvaginal mesh safety update on AUGS members’ use of synthetic mesh and biologic grafts in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(4):191–198.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cocrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2;CD012079.

- Information for Health Care Providers for POP. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/implantsandprosthetics/urogynsurgicalmesh/ucm345204.htm. Updated January 4, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2016.

- Bradley CS, Visco AG, Weber LeBrun EE, Barber MD. The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry: purpose and development [published online ahead of print January 30, 2016]. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg.

- FDA strengthens requirements for surgical mesh for the transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to address safety risks. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncementsFeiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management.

In this Article

- Transvaginal mesh and the “Hype Cycle”

- Newer vs older mesh types

- Solutions offered by the Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD, was the Keynote Speaker at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium held in Las Vegas, Nevada, December 10–12, 2015. This article was developed from Dr. Iglesia's presentation titled "The How, Why and Where of Synthetic and Biologic Mesh: Lessons Learned."