User login

Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

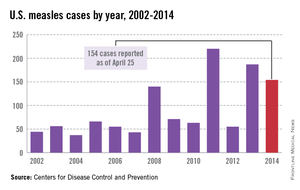

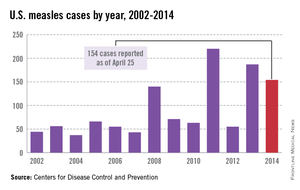

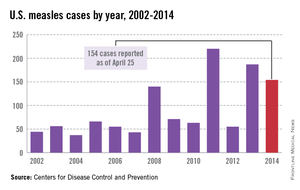

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

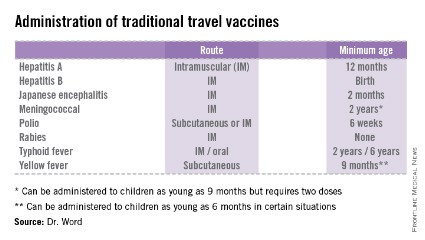

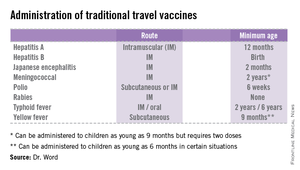

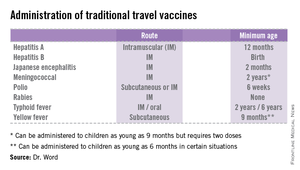

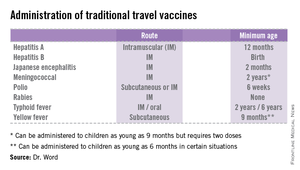

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].