User login

When depression fails to respond to initial therapy—as it commonly does—we have many options but little evidence to guide our choices. We often wonder:

- Is this patient’s depression treatment-resistant?

- Would switching medications or augmenting the initial drug be more likely to achieve an adequate response?

- How effective is psychotherapy compared with medication for treatment-resistant depression?

This article offers insights into each question, based on available trial data, algorithmic approaches to major depressive disorder, and clinical experience. Included is a preview of an ongoing multicenter, treatment-resistant depression study that mimics clinical practice and a look at vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)—a novel somatic therapy being considered by the FDA.

Measuring treatment response

Sustained symptom remission—with normalization of function—is the aim of treating major depressive disorder. Outcomes are categorized as:

- remission (virtual absence of depressive symptoms)

- response with residual symptoms (>50% reduction in baseline symptom severity that does not qualify for remission)

- partial response (>25% but <50% decrease in baseline symptom severity)

- nonresponse (<25% reduction in baseline symptoms).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is typically recurrent or chronic and characterized by marked disability and a life expectancy shortened by suicide and increased mortality from associated medical conditions. Lifetime prevalence is 16.2%.6

MDD is twice as likely to affect women as men and is common among adolescents, young adults, and persons with concurrent medical conditions.

Major depression’s course is characterized by:

- recurrent episodes (approximately every 5 years)

- or a persistent level of waxing and waning depressive symptoms (in 20% to 35% of cases).

Dysthymic disorder often heralds major depression. Within 1 year, 5% to 20% of persons with dysthymic disorder develop major depression.7

Disability associated with major depression

often exceeds that of other general medical conditions. Depression is the fourth most disabling condition worldwide and is projected to rank number two by 2020 because of its chronic and recurrent nature, high prevalence, and life-shortening effects.8

Consequences of unremitting depression include:

- poor day-to-day function (work, family)

- increased likelihood of recurrence

- psychiatric or medical complications, including substance abuse

- high use of mental health and general medical resources

- worsened prognosis of medical conditions

- high family burden.

In 8-week acute-phase trials, 7% to 15% of patients do not tolerate the initial medication, 25% show no response, 15% show partial response, 10% to 20% exhibit response with residual symptoms, and 30% to 40% achieve remission. Complicated depressions that may not respond as well include those concurrent with Axis I conditions—such as panic disorder or substance abuse—or Axis II or III conditions.1

Time-limited psychotherapies targeted at depressive symptoms (such as cognitive, interpersonal, and behavioral therapies) also typically achieve a 50% response rate in uncomplicated depression that is not treatment-resistant.

Recommendation. When treating depression, assess response at least every 4 weeks (preferably at each visit), using a self-report or clinician rating such as:

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology2 (see Related resources)

- Beck Depression Inventory3,4

- Patient Health Questionnaire.5

Defining treatment resistance

A patient may not achieve remission for a variety of reasons, including poor adherence, inadequate medication trial or dosing, occult substance abuse, undiagnosed medical conditions (Box),6-8 concurrent Axis I or II disorders, or treatment resistance.

The general consensus is to consider depression “treatment-resistant” when at least two adequately delivered treatments do not achieve at least a response. A stricter definition—failure to achieve sustained remission with two or more treatments—has also been suggested.

Several schemes have proposed treatment resistance levels, such as the five stages identified in the Table. Recent studies9,10 suggest that increasing treatment resistance is associated with decreasing response or remission rates.

Therefore, when a patient’s treatment resistance is high, two appropriate strategies are to:

- persist with and use maximally tolerated dosages of the treatment you select

- aim for response because high resistance lowers the likelihood of remission.

Predicting response. A major clinical issue is determining whether remission will occur during an acute treatment trial. It is important to not declare treatment resistance unless there has been:

- adequate exposure (dosing and duration) to the treatment

- and adequate adherence.

Patients often have apparent but not actual resistance, meaning that the agent was not used long enough (at least 6 weeks) or at high enough doses. Remission typically follows response by several weeks or even 1 to 2 months for more-chronic depressions.11 Thus, treatment trials should continue at least 12 weeks to determine whether remission will occur.

On the other hand, not obtaining at least a signal of minimal benefit (at least a 20% reduction in baseline symptom severity) in 4 to 6 weeks often portends a low likelihood of response in the long run.12,13 Thus, continue a treatment at least 6 weeks before you decide that it will not achieve a response.

Recommendation. Measure symptoms at key decision points. If modest improvement (such as 20% reduction in baseline symptoms) is found at 4 to 6 weeks, continue treating another 4 to 6 weeks, increasing the dosage as tolerated.

Table

Simple system for staging antidepressant resistance

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Failure of at least one adequate trial of one major antidepressant class |

| II | Stage I resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of an antidepressant in a distinctly different class from that used in Stage I |

| III | Stage II resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a tricyclic antidepressant |

| IV | Stage III resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor |

| V | Stage IV resistance plus failure of a course of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy |

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Thase ME, Rush AJ. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58(suppl 13):24. | |

Treatment options

When initial antidepressant treatment fails to achieve an adequate response—as it does in more than onehalf of major depression cases—the next step is to add a second agent or switch to another agent.

Available evidence14 relies almost exclusively on open, uncontrolled trials, which do not provide definitive answers. Even so, these trials indicate that nonresponse (or nonremission) with one agent does not predict nonresponse/nonremission with another.

Switching strategies. When a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is the first treatment, several open trials reveal an approximately 50% response rate to a second SSRI. However, opentrial evidence and retrospective chart review reports also indicate that switching out of class (such as from an SSRI to bupropion) is also approximately 50% effective.15

Some post hoc analyses of acute 8-week trials indicate that the dual-action agent venlafaxine at higher dosages (up to 225 mg/d of venlafaxine XR) is associated with higher remission rates than the more-selective SSRIs.16,17 On the other hand, unpublished data indicate that escitalopram, 10 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, up to 150 mg/d, did not differ in efficacy among outpatients treated by primary care physicians.18

On the other hand, sertraline and imipramine (a dual-action agent) were equally effective in a 12-week acute-phase trial.19 Furthermore, response and remission rates were similar when nonresponders in each group switched to the other antidepressant.20 This suggests that the dual-action agent (imipramine) was not more effective than the more selective agent (sertraline) in this population.

Well-controlled trials show that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be effective when tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are not. Switches among the TCAs are associated with a 30% response rate, whereas switching from a TCA to an MAOI typically results in a 50% response rate.21

Controlled prospective comparisons of two or more alternate switch or augment treatments are needed to establish comparative efficacy and tolerability.

Augmentation strategies may include lithium, buspirone, thyroid hormone (T3), stimulants, or atypical antipsychotics. Although head-to-head comparisons are rare, a randomized, controlled trial found that combining olanzapine (mean 50 mg/d), with fluoxetine (mean 15 mg/d) was more effective than each agent used alone.22

Risperidone augmentation is supported by open trials, as is the use of modafinil, other stimulants, and bupropion. An important unanswered question with most augmentation strategies is how long to continue them if they are successful.

Psychotherapy may also play a key role in augmenting medication’s effects. Keller et al23 found in chronically depressed outpatients that 12 weeks of nefazodone, up to 600 mg/d, plus cognitive behavioral analytic system psychotherapy (CBASP) produced higher response and remission rates compared with either treatment alone. A subsequent report24 found that 50% of nefa-zodone and CBASP monotherapy nonresponders did respond when switched to the alternate treatment.

Thus, CBASP may be useful at least in chronic depression to augment medication or as a “switch” to monotherapy if medication alone fails. Interestingly, Nemeroff et al25 found CBASP more effective than nefazodone for patients with chronic major depression who had a childhood history of parental loss or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.

Antidepressant tachyphylaxis—commonly referred to as “poop-out”—is reported with all antidepressants. That is, even while apparently taking their medications for 6 to 18 months, some patients lose the antidepressant effect, such that some symptoms return or a full relapse/recurrence ensues. Mechanisms of this phenomenon are unknown.

Clinically, some believe that “poop out” is more common with SSRIs than with other antidepressant classes, but no long-term comparative data support or challenge this view. Treatment options include a dosage increase, dosage reduction (especially for long half-life SSRIs such as fluoxetine), or augmentation with the options noted above (such as bupropion, buspirone, etc.).

Benefit of using algorithms

Algorithms (such as the Texas Medication Algorithm Project26 ) have suggested multiple treatment steps for major depression after initial treatment fails, with several options available at each step. Using medication algorithms has been found more effective than treatment-as-usual in outpatients with major depressive disorder.27 No studies have compared different algorithms.

STAR*D trial. The ongoing National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial may offer a new algorithmic approach to treating major depression.14,28 NIMH launched STAR*D in 1999, enrollment began in 2001, and results are expecte by May 2005 (see Related resources).

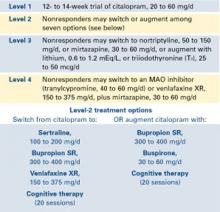

STAR*D—of which I am the study director—is a randomized, controlled, raterblinded, multisite trial of outpatients ages 18 to 75 with nonpsychotic major depression (17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score 14). The trial design includes four treatment levels and numerous antidepressant options (Figure).

The study’s aim is to enroll 4,000 patients into level 1, with 1,500 entering level 2. Patients who achieve an adequate response based on clinician judgment may continue the effective treatment for 12 months, during which their symptoms and other relevant information are monitored monthly by telephone. Patients who do not achieve an acceptable response in level 1 (or in subsequent levels) may proceed to the next level, which involves a randomized assignment.

STAR*D has an innovative design that mimics clinical practice and ensures high levels of patient participation. When patients agree to randomization, they may elect to exclude groups of treatments but may not pick a particular treatment (they must accept randomization to stay in the study).

Figure STAR*D treatment levels for major depressive disorder

For example, patient A entering level 2 may exclude switch treatments and elect to accept randomization to citalopram plus bupropion SR, citalopram plus buspirone, or citalopram and cognitive therapy. Conversely, patient B may exclude all augment options at level 2, and accept randomization to the four switch options.

Patients may exclude cognitive psychotherapy as an augment and/or switch option as long as they accept randomization to all available medication switches, or augments, or both. They may also choose cognitive therapy and exclude all medication switch and augment options. These patients must accept randomization to either cognitive therapy switch or cognitive therapy augmentation.

This so-called equipoise stratified randomized design29 allows us to compare all participants randomized to the treatments being compared. To date, only 1% of subjects have accepted randomization to all seven level-2 treatments. About one-half elect only the switch options, and about one-half elect only the augment options.

STAR*D’s goal is to determine whether there is a preferred next step for varying types and degrees of treatment-resistant repression.

Vagus nerve stimulation

Somatic therapies being investigated to expand our therapeutic options for major depressive disorder include magnetic seizure therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS).

VNS—now indicated for treatment-resistant epilepsy—is being investigated as a potential augmentation for treatment-resistant depression. An application for this supplemental indication was submitted to the FDA in October 2003.

With VNS, a device implanted in the patient’s chest provides intermittent stimulation to the left vagus nerve (typically 30 seconds on and 5 minutes off, 24 hours a day). In an open trial10 and follow-up report,30 VNS was associated with a 30% to 45% response rate in 59 depressed patients with high levels of treatment resistance (inadequate response to an average of 16 treatment trials).

VNS is well tolerated, though it has not been prospectively studied in patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Side effects that may occur when the stimulation is “on” include:

- voice alteration in about 60% of patients (the voice becomes more hoarse when the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is activated)

- paresthesias in the neck

- shortness of breath on heavy exertion.

These effects are usually absent in the 5-minute “off” phase.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. Includes the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.star-d.org

- HealthyPlace.Com Depression Community. Vagus nerve stimulation for treating depression. www.healthyplace.com/communities/depression/treatment/vns

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor, Aventyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor, Effexor XR

Disclosure

Dr. Rush receives grant/research support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and The Stanley Foundation. He is a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and a speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

1. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: depression in primary care: vol. 2. Treatment of major depression Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0551, 1993.

2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:573-83.

3. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed. manual). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 1996.

4. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561-71.

5. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13.

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289(23):3095-105.

7. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: Depression in primary care, vol. 1: detection and diagnosis Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0550, 1993.

8. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. (eds) The global burden of disease Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, 1996.

9. Barbee JG, Jamhour NJ. Lamotrigine as an augmentation agent in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(8):737-41.

10. Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;25(5):713-28.

11. Koran LM, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, et al. Sertraline versus imipramine to prevent relapse in chronic depression. J Affect Disord 2001;65(1):27-36.

12. Nierenberg AA, Feighner JP, Rudolph R, et al. Venlafaxine for treatment-resistant unipolar depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1994;14(6):419-23.

13. Quitkin FM, Petkova E, McGrath PJ, et al. When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed? Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(4):734-40.

14. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26(2):457-94.

15. Fava M, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Switching to bupropion in fluoxetine-resistant major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2003;15:17-22.

16. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:869-77.

17. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:234-41.

18. Montgomery SA, Huusom A, Bothmer J. Flexible dose comparison of s-citalopram and venlafaxine XR. J Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002;12(suppl 3):S-254.

19. Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(11):598-607.

20. Thase ME, Rush AJ, Howland RH, et al. Double-blind switch study of imipramine or sertraline treatment of antidepressant-resistant chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59(3):233-9.

21. Thase ME, Rush AJ. Treatment resistant depression. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ (eds). Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress New York: Raven Press, 1995;1081-97.

22. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, et al. A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:131-4.

23. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1462-70.

24. Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, et al. Medication or psychotherapy is effective when the other is not in chronic depression: empirical support. Arch Gen Psychiatry (submitted).

25. Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100(24):14293-6.

26. Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(3):142-56.

27. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Crismon ML, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP): clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (in press).

28. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. for the STAR*D Investigators Group. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004;25(1):118-41.

29. Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:792-801.

30. Marangell LB, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for major depressive episodes: one-year outcomes. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51(4):280-7.

When depression fails to respond to initial therapy—as it commonly does—we have many options but little evidence to guide our choices. We often wonder:

- Is this patient’s depression treatment-resistant?

- Would switching medications or augmenting the initial drug be more likely to achieve an adequate response?

- How effective is psychotherapy compared with medication for treatment-resistant depression?

This article offers insights into each question, based on available trial data, algorithmic approaches to major depressive disorder, and clinical experience. Included is a preview of an ongoing multicenter, treatment-resistant depression study that mimics clinical practice and a look at vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)—a novel somatic therapy being considered by the FDA.

Measuring treatment response

Sustained symptom remission—with normalization of function—is the aim of treating major depressive disorder. Outcomes are categorized as:

- remission (virtual absence of depressive symptoms)

- response with residual symptoms (>50% reduction in baseline symptom severity that does not qualify for remission)

- partial response (>25% but <50% decrease in baseline symptom severity)

- nonresponse (<25% reduction in baseline symptoms).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is typically recurrent or chronic and characterized by marked disability and a life expectancy shortened by suicide and increased mortality from associated medical conditions. Lifetime prevalence is 16.2%.6

MDD is twice as likely to affect women as men and is common among adolescents, young adults, and persons with concurrent medical conditions.

Major depression’s course is characterized by:

- recurrent episodes (approximately every 5 years)

- or a persistent level of waxing and waning depressive symptoms (in 20% to 35% of cases).

Dysthymic disorder often heralds major depression. Within 1 year, 5% to 20% of persons with dysthymic disorder develop major depression.7

Disability associated with major depression

often exceeds that of other general medical conditions. Depression is the fourth most disabling condition worldwide and is projected to rank number two by 2020 because of its chronic and recurrent nature, high prevalence, and life-shortening effects.8

Consequences of unremitting depression include:

- poor day-to-day function (work, family)

- increased likelihood of recurrence

- psychiatric or medical complications, including substance abuse

- high use of mental health and general medical resources

- worsened prognosis of medical conditions

- high family burden.

In 8-week acute-phase trials, 7% to 15% of patients do not tolerate the initial medication, 25% show no response, 15% show partial response, 10% to 20% exhibit response with residual symptoms, and 30% to 40% achieve remission. Complicated depressions that may not respond as well include those concurrent with Axis I conditions—such as panic disorder or substance abuse—or Axis II or III conditions.1

Time-limited psychotherapies targeted at depressive symptoms (such as cognitive, interpersonal, and behavioral therapies) also typically achieve a 50% response rate in uncomplicated depression that is not treatment-resistant.

Recommendation. When treating depression, assess response at least every 4 weeks (preferably at each visit), using a self-report or clinician rating such as:

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology2 (see Related resources)

- Beck Depression Inventory3,4

- Patient Health Questionnaire.5

Defining treatment resistance

A patient may not achieve remission for a variety of reasons, including poor adherence, inadequate medication trial or dosing, occult substance abuse, undiagnosed medical conditions (Box),6-8 concurrent Axis I or II disorders, or treatment resistance.

The general consensus is to consider depression “treatment-resistant” when at least two adequately delivered treatments do not achieve at least a response. A stricter definition—failure to achieve sustained remission with two or more treatments—has also been suggested.

Several schemes have proposed treatment resistance levels, such as the five stages identified in the Table. Recent studies9,10 suggest that increasing treatment resistance is associated with decreasing response or remission rates.

Therefore, when a patient’s treatment resistance is high, two appropriate strategies are to:

- persist with and use maximally tolerated dosages of the treatment you select

- aim for response because high resistance lowers the likelihood of remission.

Predicting response. A major clinical issue is determining whether remission will occur during an acute treatment trial. It is important to not declare treatment resistance unless there has been:

- adequate exposure (dosing and duration) to the treatment

- and adequate adherence.

Patients often have apparent but not actual resistance, meaning that the agent was not used long enough (at least 6 weeks) or at high enough doses. Remission typically follows response by several weeks or even 1 to 2 months for more-chronic depressions.11 Thus, treatment trials should continue at least 12 weeks to determine whether remission will occur.

On the other hand, not obtaining at least a signal of minimal benefit (at least a 20% reduction in baseline symptom severity) in 4 to 6 weeks often portends a low likelihood of response in the long run.12,13 Thus, continue a treatment at least 6 weeks before you decide that it will not achieve a response.

Recommendation. Measure symptoms at key decision points. If modest improvement (such as 20% reduction in baseline symptoms) is found at 4 to 6 weeks, continue treating another 4 to 6 weeks, increasing the dosage as tolerated.

Table

Simple system for staging antidepressant resistance

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Failure of at least one adequate trial of one major antidepressant class |

| II | Stage I resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of an antidepressant in a distinctly different class from that used in Stage I |

| III | Stage II resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a tricyclic antidepressant |

| IV | Stage III resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor |

| V | Stage IV resistance plus failure of a course of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy |

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Thase ME, Rush AJ. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58(suppl 13):24. | |

Treatment options

When initial antidepressant treatment fails to achieve an adequate response—as it does in more than onehalf of major depression cases—the next step is to add a second agent or switch to another agent.

Available evidence14 relies almost exclusively on open, uncontrolled trials, which do not provide definitive answers. Even so, these trials indicate that nonresponse (or nonremission) with one agent does not predict nonresponse/nonremission with another.

Switching strategies. When a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is the first treatment, several open trials reveal an approximately 50% response rate to a second SSRI. However, opentrial evidence and retrospective chart review reports also indicate that switching out of class (such as from an SSRI to bupropion) is also approximately 50% effective.15

Some post hoc analyses of acute 8-week trials indicate that the dual-action agent venlafaxine at higher dosages (up to 225 mg/d of venlafaxine XR) is associated with higher remission rates than the more-selective SSRIs.16,17 On the other hand, unpublished data indicate that escitalopram, 10 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, up to 150 mg/d, did not differ in efficacy among outpatients treated by primary care physicians.18

On the other hand, sertraline and imipramine (a dual-action agent) were equally effective in a 12-week acute-phase trial.19 Furthermore, response and remission rates were similar when nonresponders in each group switched to the other antidepressant.20 This suggests that the dual-action agent (imipramine) was not more effective than the more selective agent (sertraline) in this population.

Well-controlled trials show that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be effective when tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are not. Switches among the TCAs are associated with a 30% response rate, whereas switching from a TCA to an MAOI typically results in a 50% response rate.21

Controlled prospective comparisons of two or more alternate switch or augment treatments are needed to establish comparative efficacy and tolerability.

Augmentation strategies may include lithium, buspirone, thyroid hormone (T3), stimulants, or atypical antipsychotics. Although head-to-head comparisons are rare, a randomized, controlled trial found that combining olanzapine (mean 50 mg/d), with fluoxetine (mean 15 mg/d) was more effective than each agent used alone.22

Risperidone augmentation is supported by open trials, as is the use of modafinil, other stimulants, and bupropion. An important unanswered question with most augmentation strategies is how long to continue them if they are successful.

Psychotherapy may also play a key role in augmenting medication’s effects. Keller et al23 found in chronically depressed outpatients that 12 weeks of nefazodone, up to 600 mg/d, plus cognitive behavioral analytic system psychotherapy (CBASP) produced higher response and remission rates compared with either treatment alone. A subsequent report24 found that 50% of nefa-zodone and CBASP monotherapy nonresponders did respond when switched to the alternate treatment.

Thus, CBASP may be useful at least in chronic depression to augment medication or as a “switch” to monotherapy if medication alone fails. Interestingly, Nemeroff et al25 found CBASP more effective than nefazodone for patients with chronic major depression who had a childhood history of parental loss or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.

Antidepressant tachyphylaxis—commonly referred to as “poop-out”—is reported with all antidepressants. That is, even while apparently taking their medications for 6 to 18 months, some patients lose the antidepressant effect, such that some symptoms return or a full relapse/recurrence ensues. Mechanisms of this phenomenon are unknown.

Clinically, some believe that “poop out” is more common with SSRIs than with other antidepressant classes, but no long-term comparative data support or challenge this view. Treatment options include a dosage increase, dosage reduction (especially for long half-life SSRIs such as fluoxetine), or augmentation with the options noted above (such as bupropion, buspirone, etc.).

Benefit of using algorithms

Algorithms (such as the Texas Medication Algorithm Project26 ) have suggested multiple treatment steps for major depression after initial treatment fails, with several options available at each step. Using medication algorithms has been found more effective than treatment-as-usual in outpatients with major depressive disorder.27 No studies have compared different algorithms.

STAR*D trial. The ongoing National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial may offer a new algorithmic approach to treating major depression.14,28 NIMH launched STAR*D in 1999, enrollment began in 2001, and results are expecte by May 2005 (see Related resources).

STAR*D—of which I am the study director—is a randomized, controlled, raterblinded, multisite trial of outpatients ages 18 to 75 with nonpsychotic major depression (17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score 14). The trial design includes four treatment levels and numerous antidepressant options (Figure).

The study’s aim is to enroll 4,000 patients into level 1, with 1,500 entering level 2. Patients who achieve an adequate response based on clinician judgment may continue the effective treatment for 12 months, during which their symptoms and other relevant information are monitored monthly by telephone. Patients who do not achieve an acceptable response in level 1 (or in subsequent levels) may proceed to the next level, which involves a randomized assignment.

STAR*D has an innovative design that mimics clinical practice and ensures high levels of patient participation. When patients agree to randomization, they may elect to exclude groups of treatments but may not pick a particular treatment (they must accept randomization to stay in the study).

Figure STAR*D treatment levels for major depressive disorder

For example, patient A entering level 2 may exclude switch treatments and elect to accept randomization to citalopram plus bupropion SR, citalopram plus buspirone, or citalopram and cognitive therapy. Conversely, patient B may exclude all augment options at level 2, and accept randomization to the four switch options.

Patients may exclude cognitive psychotherapy as an augment and/or switch option as long as they accept randomization to all available medication switches, or augments, or both. They may also choose cognitive therapy and exclude all medication switch and augment options. These patients must accept randomization to either cognitive therapy switch or cognitive therapy augmentation.

This so-called equipoise stratified randomized design29 allows us to compare all participants randomized to the treatments being compared. To date, only 1% of subjects have accepted randomization to all seven level-2 treatments. About one-half elect only the switch options, and about one-half elect only the augment options.

STAR*D’s goal is to determine whether there is a preferred next step for varying types and degrees of treatment-resistant repression.

Vagus nerve stimulation

Somatic therapies being investigated to expand our therapeutic options for major depressive disorder include magnetic seizure therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS).

VNS—now indicated for treatment-resistant epilepsy—is being investigated as a potential augmentation for treatment-resistant depression. An application for this supplemental indication was submitted to the FDA in October 2003.

With VNS, a device implanted in the patient’s chest provides intermittent stimulation to the left vagus nerve (typically 30 seconds on and 5 minutes off, 24 hours a day). In an open trial10 and follow-up report,30 VNS was associated with a 30% to 45% response rate in 59 depressed patients with high levels of treatment resistance (inadequate response to an average of 16 treatment trials).

VNS is well tolerated, though it has not been prospectively studied in patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Side effects that may occur when the stimulation is “on” include:

- voice alteration in about 60% of patients (the voice becomes more hoarse when the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is activated)

- paresthesias in the neck

- shortness of breath on heavy exertion.

These effects are usually absent in the 5-minute “off” phase.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. Includes the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.star-d.org

- HealthyPlace.Com Depression Community. Vagus nerve stimulation for treating depression. www.healthyplace.com/communities/depression/treatment/vns

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor, Aventyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor, Effexor XR

Disclosure

Dr. Rush receives grant/research support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and The Stanley Foundation. He is a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and a speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

When depression fails to respond to initial therapy—as it commonly does—we have many options but little evidence to guide our choices. We often wonder:

- Is this patient’s depression treatment-resistant?

- Would switching medications or augmenting the initial drug be more likely to achieve an adequate response?

- How effective is psychotherapy compared with medication for treatment-resistant depression?

This article offers insights into each question, based on available trial data, algorithmic approaches to major depressive disorder, and clinical experience. Included is a preview of an ongoing multicenter, treatment-resistant depression study that mimics clinical practice and a look at vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)—a novel somatic therapy being considered by the FDA.

Measuring treatment response

Sustained symptom remission—with normalization of function—is the aim of treating major depressive disorder. Outcomes are categorized as:

- remission (virtual absence of depressive symptoms)

- response with residual symptoms (>50% reduction in baseline symptom severity that does not qualify for remission)

- partial response (>25% but <50% decrease in baseline symptom severity)

- nonresponse (<25% reduction in baseline symptoms).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is typically recurrent or chronic and characterized by marked disability and a life expectancy shortened by suicide and increased mortality from associated medical conditions. Lifetime prevalence is 16.2%.6

MDD is twice as likely to affect women as men and is common among adolescents, young adults, and persons with concurrent medical conditions.

Major depression’s course is characterized by:

- recurrent episodes (approximately every 5 years)

- or a persistent level of waxing and waning depressive symptoms (in 20% to 35% of cases).

Dysthymic disorder often heralds major depression. Within 1 year, 5% to 20% of persons with dysthymic disorder develop major depression.7

Disability associated with major depression

often exceeds that of other general medical conditions. Depression is the fourth most disabling condition worldwide and is projected to rank number two by 2020 because of its chronic and recurrent nature, high prevalence, and life-shortening effects.8

Consequences of unremitting depression include:

- poor day-to-day function (work, family)

- increased likelihood of recurrence

- psychiatric or medical complications, including substance abuse

- high use of mental health and general medical resources

- worsened prognosis of medical conditions

- high family burden.

In 8-week acute-phase trials, 7% to 15% of patients do not tolerate the initial medication, 25% show no response, 15% show partial response, 10% to 20% exhibit response with residual symptoms, and 30% to 40% achieve remission. Complicated depressions that may not respond as well include those concurrent with Axis I conditions—such as panic disorder or substance abuse—or Axis II or III conditions.1

Time-limited psychotherapies targeted at depressive symptoms (such as cognitive, interpersonal, and behavioral therapies) also typically achieve a 50% response rate in uncomplicated depression that is not treatment-resistant.

Recommendation. When treating depression, assess response at least every 4 weeks (preferably at each visit), using a self-report or clinician rating such as:

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology2 (see Related resources)

- Beck Depression Inventory3,4

- Patient Health Questionnaire.5

Defining treatment resistance

A patient may not achieve remission for a variety of reasons, including poor adherence, inadequate medication trial or dosing, occult substance abuse, undiagnosed medical conditions (Box),6-8 concurrent Axis I or II disorders, or treatment resistance.

The general consensus is to consider depression “treatment-resistant” when at least two adequately delivered treatments do not achieve at least a response. A stricter definition—failure to achieve sustained remission with two or more treatments—has also been suggested.

Several schemes have proposed treatment resistance levels, such as the five stages identified in the Table. Recent studies9,10 suggest that increasing treatment resistance is associated with decreasing response or remission rates.

Therefore, when a patient’s treatment resistance is high, two appropriate strategies are to:

- persist with and use maximally tolerated dosages of the treatment you select

- aim for response because high resistance lowers the likelihood of remission.

Predicting response. A major clinical issue is determining whether remission will occur during an acute treatment trial. It is important to not declare treatment resistance unless there has been:

- adequate exposure (dosing and duration) to the treatment

- and adequate adherence.

Patients often have apparent but not actual resistance, meaning that the agent was not used long enough (at least 6 weeks) or at high enough doses. Remission typically follows response by several weeks or even 1 to 2 months for more-chronic depressions.11 Thus, treatment trials should continue at least 12 weeks to determine whether remission will occur.

On the other hand, not obtaining at least a signal of minimal benefit (at least a 20% reduction in baseline symptom severity) in 4 to 6 weeks often portends a low likelihood of response in the long run.12,13 Thus, continue a treatment at least 6 weeks before you decide that it will not achieve a response.

Recommendation. Measure symptoms at key decision points. If modest improvement (such as 20% reduction in baseline symptoms) is found at 4 to 6 weeks, continue treating another 4 to 6 weeks, increasing the dosage as tolerated.

Table

Simple system for staging antidepressant resistance

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Failure of at least one adequate trial of one major antidepressant class |

| II | Stage I resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of an antidepressant in a distinctly different class from that used in Stage I |

| III | Stage II resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a tricyclic antidepressant |

| IV | Stage III resistance plus failure of an adequate trial of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor |

| V | Stage IV resistance plus failure of a course of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy |

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Thase ME, Rush AJ. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58(suppl 13):24. | |

Treatment options

When initial antidepressant treatment fails to achieve an adequate response—as it does in more than onehalf of major depression cases—the next step is to add a second agent or switch to another agent.

Available evidence14 relies almost exclusively on open, uncontrolled trials, which do not provide definitive answers. Even so, these trials indicate that nonresponse (or nonremission) with one agent does not predict nonresponse/nonremission with another.

Switching strategies. When a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is the first treatment, several open trials reveal an approximately 50% response rate to a second SSRI. However, opentrial evidence and retrospective chart review reports also indicate that switching out of class (such as from an SSRI to bupropion) is also approximately 50% effective.15

Some post hoc analyses of acute 8-week trials indicate that the dual-action agent venlafaxine at higher dosages (up to 225 mg/d of venlafaxine XR) is associated with higher remission rates than the more-selective SSRIs.16,17 On the other hand, unpublished data indicate that escitalopram, 10 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, up to 150 mg/d, did not differ in efficacy among outpatients treated by primary care physicians.18

On the other hand, sertraline and imipramine (a dual-action agent) were equally effective in a 12-week acute-phase trial.19 Furthermore, response and remission rates were similar when nonresponders in each group switched to the other antidepressant.20 This suggests that the dual-action agent (imipramine) was not more effective than the more selective agent (sertraline) in this population.

Well-controlled trials show that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be effective when tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are not. Switches among the TCAs are associated with a 30% response rate, whereas switching from a TCA to an MAOI typically results in a 50% response rate.21

Controlled prospective comparisons of two or more alternate switch or augment treatments are needed to establish comparative efficacy and tolerability.

Augmentation strategies may include lithium, buspirone, thyroid hormone (T3), stimulants, or atypical antipsychotics. Although head-to-head comparisons are rare, a randomized, controlled trial found that combining olanzapine (mean 50 mg/d), with fluoxetine (mean 15 mg/d) was more effective than each agent used alone.22

Risperidone augmentation is supported by open trials, as is the use of modafinil, other stimulants, and bupropion. An important unanswered question with most augmentation strategies is how long to continue them if they are successful.

Psychotherapy may also play a key role in augmenting medication’s effects. Keller et al23 found in chronically depressed outpatients that 12 weeks of nefazodone, up to 600 mg/d, plus cognitive behavioral analytic system psychotherapy (CBASP) produced higher response and remission rates compared with either treatment alone. A subsequent report24 found that 50% of nefa-zodone and CBASP monotherapy nonresponders did respond when switched to the alternate treatment.

Thus, CBASP may be useful at least in chronic depression to augment medication or as a “switch” to monotherapy if medication alone fails. Interestingly, Nemeroff et al25 found CBASP more effective than nefazodone for patients with chronic major depression who had a childhood history of parental loss or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.

Antidepressant tachyphylaxis—commonly referred to as “poop-out”—is reported with all antidepressants. That is, even while apparently taking their medications for 6 to 18 months, some patients lose the antidepressant effect, such that some symptoms return or a full relapse/recurrence ensues. Mechanisms of this phenomenon are unknown.

Clinically, some believe that “poop out” is more common with SSRIs than with other antidepressant classes, but no long-term comparative data support or challenge this view. Treatment options include a dosage increase, dosage reduction (especially for long half-life SSRIs such as fluoxetine), or augmentation with the options noted above (such as bupropion, buspirone, etc.).

Benefit of using algorithms

Algorithms (such as the Texas Medication Algorithm Project26 ) have suggested multiple treatment steps for major depression after initial treatment fails, with several options available at each step. Using medication algorithms has been found more effective than treatment-as-usual in outpatients with major depressive disorder.27 No studies have compared different algorithms.

STAR*D trial. The ongoing National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial may offer a new algorithmic approach to treating major depression.14,28 NIMH launched STAR*D in 1999, enrollment began in 2001, and results are expecte by May 2005 (see Related resources).

STAR*D—of which I am the study director—is a randomized, controlled, raterblinded, multisite trial of outpatients ages 18 to 75 with nonpsychotic major depression (17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score 14). The trial design includes four treatment levels and numerous antidepressant options (Figure).

The study’s aim is to enroll 4,000 patients into level 1, with 1,500 entering level 2. Patients who achieve an adequate response based on clinician judgment may continue the effective treatment for 12 months, during which their symptoms and other relevant information are monitored monthly by telephone. Patients who do not achieve an acceptable response in level 1 (or in subsequent levels) may proceed to the next level, which involves a randomized assignment.

STAR*D has an innovative design that mimics clinical practice and ensures high levels of patient participation. When patients agree to randomization, they may elect to exclude groups of treatments but may not pick a particular treatment (they must accept randomization to stay in the study).

Figure STAR*D treatment levels for major depressive disorder

For example, patient A entering level 2 may exclude switch treatments and elect to accept randomization to citalopram plus bupropion SR, citalopram plus buspirone, or citalopram and cognitive therapy. Conversely, patient B may exclude all augment options at level 2, and accept randomization to the four switch options.

Patients may exclude cognitive psychotherapy as an augment and/or switch option as long as they accept randomization to all available medication switches, or augments, or both. They may also choose cognitive therapy and exclude all medication switch and augment options. These patients must accept randomization to either cognitive therapy switch or cognitive therapy augmentation.

This so-called equipoise stratified randomized design29 allows us to compare all participants randomized to the treatments being compared. To date, only 1% of subjects have accepted randomization to all seven level-2 treatments. About one-half elect only the switch options, and about one-half elect only the augment options.

STAR*D’s goal is to determine whether there is a preferred next step for varying types and degrees of treatment-resistant repression.

Vagus nerve stimulation

Somatic therapies being investigated to expand our therapeutic options for major depressive disorder include magnetic seizure therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS).

VNS—now indicated for treatment-resistant epilepsy—is being investigated as a potential augmentation for treatment-resistant depression. An application for this supplemental indication was submitted to the FDA in October 2003.

With VNS, a device implanted in the patient’s chest provides intermittent stimulation to the left vagus nerve (typically 30 seconds on and 5 minutes off, 24 hours a day). In an open trial10 and follow-up report,30 VNS was associated with a 30% to 45% response rate in 59 depressed patients with high levels of treatment resistance (inadequate response to an average of 16 treatment trials).

VNS is well tolerated, though it has not been prospectively studied in patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Side effects that may occur when the stimulation is “on” include:

- voice alteration in about 60% of patients (the voice becomes more hoarse when the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is activated)

- paresthesias in the neck

- shortness of breath on heavy exertion.

These effects are usually absent in the 5-minute “off” phase.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. Includes the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.star-d.org

- HealthyPlace.Com Depression Community. Vagus nerve stimulation for treating depression. www.healthyplace.com/communities/depression/treatment/vns

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor, Aventyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor, Effexor XR

Disclosure

Dr. Rush receives grant/research support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and The Stanley Foundation. He is a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and a speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

1. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: depression in primary care: vol. 2. Treatment of major depression Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0551, 1993.

2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:573-83.

3. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed. manual). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 1996.

4. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561-71.

5. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13.

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289(23):3095-105.

7. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: Depression in primary care, vol. 1: detection and diagnosis Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0550, 1993.

8. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. (eds) The global burden of disease Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, 1996.

9. Barbee JG, Jamhour NJ. Lamotrigine as an augmentation agent in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(8):737-41.

10. Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;25(5):713-28.

11. Koran LM, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, et al. Sertraline versus imipramine to prevent relapse in chronic depression. J Affect Disord 2001;65(1):27-36.

12. Nierenberg AA, Feighner JP, Rudolph R, et al. Venlafaxine for treatment-resistant unipolar depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1994;14(6):419-23.

13. Quitkin FM, Petkova E, McGrath PJ, et al. When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed? Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(4):734-40.

14. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26(2):457-94.

15. Fava M, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Switching to bupropion in fluoxetine-resistant major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2003;15:17-22.

16. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:869-77.

17. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:234-41.

18. Montgomery SA, Huusom A, Bothmer J. Flexible dose comparison of s-citalopram and venlafaxine XR. J Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002;12(suppl 3):S-254.

19. Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(11):598-607.

20. Thase ME, Rush AJ, Howland RH, et al. Double-blind switch study of imipramine or sertraline treatment of antidepressant-resistant chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59(3):233-9.

21. Thase ME, Rush AJ. Treatment resistant depression. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ (eds). Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress New York: Raven Press, 1995;1081-97.

22. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, et al. A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:131-4.

23. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1462-70.

24. Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, et al. Medication or psychotherapy is effective when the other is not in chronic depression: empirical support. Arch Gen Psychiatry (submitted).

25. Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100(24):14293-6.

26. Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(3):142-56.

27. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Crismon ML, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP): clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (in press).

28. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. for the STAR*D Investigators Group. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004;25(1):118-41.

29. Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:792-801.

30. Marangell LB, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for major depressive episodes: one-year outcomes. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51(4):280-7.

1. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: depression in primary care: vol. 2. Treatment of major depression Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0551, 1993.

2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:573-83.

3. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed. manual). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 1996.

4. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561-71.

5. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13.

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289(23):3095-105.

7. Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline, number 5: Depression in primary care, vol. 1: detection and diagnosis Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR publication no. 93-0550, 1993.

8. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. (eds) The global burden of disease Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, 1996.

9. Barbee JG, Jamhour NJ. Lamotrigine as an augmentation agent in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(8):737-41.

10. Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;25(5):713-28.

11. Koran LM, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, et al. Sertraline versus imipramine to prevent relapse in chronic depression. J Affect Disord 2001;65(1):27-36.

12. Nierenberg AA, Feighner JP, Rudolph R, et al. Venlafaxine for treatment-resistant unipolar depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1994;14(6):419-23.

13. Quitkin FM, Petkova E, McGrath PJ, et al. When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed? Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(4):734-40.

14. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26(2):457-94.

15. Fava M, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Switching to bupropion in fluoxetine-resistant major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2003;15:17-22.

16. Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:869-77.

17. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:234-41.

18. Montgomery SA, Huusom A, Bothmer J. Flexible dose comparison of s-citalopram and venlafaxine XR. J Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002;12(suppl 3):S-254.

19. Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(11):598-607.

20. Thase ME, Rush AJ, Howland RH, et al. Double-blind switch study of imipramine or sertraline treatment of antidepressant-resistant chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59(3):233-9.

21. Thase ME, Rush AJ. Treatment resistant depression. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ (eds). Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress New York: Raven Press, 1995;1081-97.

22. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, et al. A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:131-4.

23. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1462-70.

24. Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, et al. Medication or psychotherapy is effective when the other is not in chronic depression: empirical support. Arch Gen Psychiatry (submitted).

25. Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100(24):14293-6.

26. Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(3):142-56.

27. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Crismon ML, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP): clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (in press).

28. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. for the STAR*D Investigators Group. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004;25(1):118-41.

29. Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:792-801.

30. Marangell LB, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for major depressive episodes: one-year outcomes. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51(4):280-7.