User login

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene

(and when you should not)

Kari P. Braaten, MD, MPH; Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

The past 20 years have seen an explosion of new contraceptive technologies; women benefit now from a range of effective methods that can satisfy their preferences. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies jumped on board, developing and marketing new hormonal combinations, delivery systems, and inexpensive devices that offer them opportunity for great profit.

Now that many of these newer products have been available for a decade or longer, the combined motivation of women, health-care providers, and industry should have meant better success in preventing undesired pregnancies. Regrettably, we’re moving in the wrong direction: The rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States has increased.

In this Update, we address the sobering reality of the unintended pregnancy rate over 20 years. We then take the opportunity to:

- review new data and guidelines about postpartum and postprocedure insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- explain the latest data and recommendations on venous thrombotic events and combined hormonal methods

- discuss the possibility of an association between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and acquisition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

What are the national data on unintended pregnancy?

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

For decades, we’ve been repeating ourselves about the scope of the problem of unintended pregnancy—namely, “about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended,” etc. The fact that this rate has not improved in nearly 20 years is, in itself, worrisome; despite a proliferation of methods of contraception (and the hope that added options would cause the high rate of unintended pregnancy to fall), an overall benefit hasn’t been realized.

A small, but very important, decrease in the percentage of pregnancies that are unintended—from 49.2% to 48%—occurred between 1994 and 2001.1 New data assembled by Finer and Zolna show, however, that the percentage has crept back up to 49%.

The unintended pregnancy rate is another way to measure this outcome—reflecting the number of unintended pregnancies for every 1,000 women of reproductive age. The lowest rate (44.7) was seen in 1994; by 2006, the rate had increased to 52—just shy of the highest rate of 52.6 that was reported in the early 1980s.

Why haven’t new methods lowered the unintended pregnancy rate?

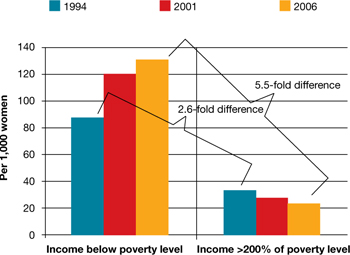

Both unintended pregnancy and abortion affect poorer and younger women disproportionately. In 1994, the unintended pregnancy rate among women who were below the poverty level was 2.6-fold higher than the rate among women who were 200% above the poverty level. That difference in rate increased to 5.5-fold higher by 2006 (FIGURE). The unintended pregnancy rate has increased significantly among poor women while it has continued to decrease among women who are not poor.

The “poverty gap” has been widening in the US rate of unintended pregnancy

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Why has this happened? Perhaps newer contraceptive methods aren’t being used by, or are not available to, women who are most in need. This regrettable trend is a demonstration that unintended pregnancy is a social issue—that there are, without question, “haves” and “have-nots.”

Black women have an unintended pregnancy rate nearly double that of non-Hispanic white women, and are more likely than non-Hispanic white women to opt for an abortion when faced with an unintended pregnancy. New data also show that, from 2005 to 2008, the number of abortions and the abortion rate in the United States have remained approximately the same.2 While the rate of unintended pregnancy increases, therefore, principally among poor women, more of those pregnancies are being continued.

Contraception, recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most important public health advances of the past century, is not having a maximal impact in the United States.3 The primary goal of contraception is to prevent unintended pregnancy; we have not continued to make strides in the last two decades against the unintended pregnancy rate so that women control when they have children and how many they have.

Advertising for contraceptives cannot take the place of education by physicians. Your care of reproductive-age women should include finding an opportunity, at every visit, to address, and educate them on, contraception.

Even more important, primary care physicians—whose ability to offer such highly effective options as IUDs, implants, and sterilization might be limited—need to be better educated to ensure that they 1) provide contraceptive counseling to women and 2) refer patients to a gynecologist or a trained primary care provider who can offer them access to the most appropriate of the full range of methods.

A final note: Continued advocacy of contraception as an important component of primary preventive medicine by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) should mean better support for seasoned providers and new trainees to give contraception and family planning the clinical attention it needs.

More evidence on postpregnancy IUD placement

Bednarek PH, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Cwiak C, Espey E, Jensen JT; Post-Aspiration IUD Randomization (PAIR) Study Trial Group. Immediate versus delayed IUD insertion after uterine aspiration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2208–2217.

Cremer M, Bullard KA, Mosley RM, et al. Immediate vs. delayed post-abortal copper T 380A IUD insertion in cases over 12 weeks of gestation. Contraception. 2011;83(6):522–527.

Hohmann HL, Reeves MF, Chen BA, Perriera LK, Hayes JL, Creinin MD. Immediate versus delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device following dilation and evacuation: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2012;85(3):240–245.

Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, Rosario L, Westhoff C. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):623–628.

Betstadt SJ, Turok DK, Kapp N, Feng KT, Borgatta L. Intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Contraception. 2011;83(6):517–521.

Celen S, Sucak A, Yildiz Y, Danisman N. Immediate postplacental insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device during cesarean section. Contraception. 2011;84(3):240–243.

Intrauterine devices have received a great deal of attention in recent years. Indeed, the utilization rate has increased significantly, with 5.5% of contraceptive users—2.1 million women—now using an IUD.4 Although most women who use an IUD obtain it at an outpatient office, remote from pregnancy and where the safety profile and risk of expulsion are well documented, many women who desire effective contraception like an IUD may not be seen by a provider until they are pregnant.

A significant body of data has been published recently on the role of postpregnancy IUD placement, adding important information to the existing body of literature.

Multicenter randomized trial. A study in the United States by Bednarek and co-workers demonstrated that immediate post-aspiration placement of an IUD resulted in a higher rate (>90%) of IUD utilization at 6 months than did insertion 6 to 8 weeks postpartum (just above 75%). Furthermore, five pregnancies were documented in the group with delayed IUD insertion; none were seen in the immediate-insertion group.

Independent randomized trials. Two studies (by Cremer and colleagues and Hohmann and colleagues) showed that immediate post-dilation and evacuation placement of an IUD also yielded a significantly higher rate of continued usage at 6 months than did delayed placement. (The terms “postaspiration” and “post–dilation and evacuation” are important as they encompass elective termination procedures for miscarriage management and fetal demise among women who may have undesired fertility.) For women having such procedures who do not want another pregnancy in the near future, immediate provision of highly effective contraception can best be performed at the time of the procedure.

New data: Use of IUD after medical abortion. A randomized trial conducted by Shimoni and colleagues showed 1) no significant difference in expulsion after immediate versus delayed placement and 2) several pregnancies in the delayed group. Regrettably, the investigators did not clearly define “immediate placement.”

In another prospective cohort study, Betstadt and coworkers reported a low rate of expulsion (4.1%) when an IUD was placed within 14 days after confirmed medical abortion. The findings of that study were also limited because the researchers followed women for only 3 months after the IUD was placed.

These new studies shed important light on the safety and tolerability of immediate IUD insertion. More questions remain, however, about ideal timing of placement after medical abortion. Postpartum IUDs have also been promoted as an important method of effective contraception despite higher expulsion rates than interval insertion, which must be compared to the high rate of loss to follow-up.5

Prospective cohort study. A well-designed study recently addressed outcomes of post-placental IUD placement during cesarean delivery. Celen and colleagues followed 245 women for longer than 1 year after postplacental copper-T IUD placement and reported a 17% cumulative expulsion rate and an overall continuation rate of 62%. These rates are not significantly lower than the cumulative expulsion rate and overall continuation rate associated with postplacental insertion after vaginal delivery. The investigators also reported no increased risk of serious complications, infection, or perforation with postplacental IUD placement after cesarean delivery.

The necessity of coming to clinic in the months right after the end of a pregnancy to obtain highly effective contraception is, for women who are in this position, a well-established barrier to ensuring that they receive the protection they want. We now have important data showing that IUD placement after suction aspiration, dilation and evacuation, cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery6 is effective and causes minimal side effects.

Better data are needed before we can make a universal recommendation about inserting an IUD shortly after medical abortion.

Overall, you should consider that the reversibility and known safety profile of an IUD continue to make this device an ideal contraceptive for many women.

VTE risk, postpartum hormonal contraception, and progestin type

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010: Revised recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(26):878–883.

Lidegaard O, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, Skjeldestad FE, Lokkegaard E. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001–9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC) increases a woman’s risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), an effect that has been attributed to the thrombogenic effects of estrogen.7 The combined risk of VTE from CHC and the known independent risk of VTE postpartum has prompted the CDC to recommend against the use of any combined (i.e., estrogen-containing) method for 21 days postpartum. Although no direct evidence exists of a higher rate of VTE with CHC immediately postpartum, indirect evidence of increased risk should be considered very seriously.

Evidence from retrospective and database studies continues to suggest that one of the newer progestins, drospirenone, may play a larger role in VTE than previously understood, reigniting the debate over the risk of VTE and combined oral contraceptives (OCs).

Drospirenone was introduced in 2001 in combination with ethinyl estradiol in an OC that had the added benefits of alleviating acne and controlling premenstrual symptoms.8 A large (142,475 woman-years) prospective trial examining the role of drospirenone showed no significant difference between this hormone and other forms of progesterone in regard to adverse cardiovascular events.9 This study had minimal loss to follow-up (2.4%) and is the only cohort to confirm VTE outcomes based on medical records review (rather than insurance claims databases or national registries).10

A national cohort study in Denmark, published in 2009, found that the risk of VTE was directly related to duration of use and the dosage of estrogen.11 More significantly, those investigators found that specific progestin types, including drospirenone, desogestrel, and gestodene, were also associated with increased VTE risk.

Danish researchers conducted another retrospective study to assess the VTE risk associated with drospirenone in CHC—a review that included other progestins, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, and progestin-only pills. The results again suggested that contraceptives that contain drospirenone, desogestrel, or gestodene were associated with more than twice the risk of VTE, compared with OCs that contain levonorgestrel.

For gestodene and desogestrel, increasing the dosage of estrogen increased the risk of VTE; for drospirenone, however, the dosage of estrogen did not affect the rate of VTE. No association was found between the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD or progestin-only pills with VTE. Overall, the absolute number of VTE was small (4,307 VTE among 1.3 million women using hormonal contraception), which is reassuring, considering that this was a large cohort study.

No combination hormonal contraception (CHC) of any type should be prescribed for use during the 3 weeks after delivery, given indirect evidence of increased risk of VTE during this period and the known VTE risk posed by CHC.

For women who are beyond that window and who want CHC, the question becomes: How should you counsel them about progestins in different formulations?

A decade of research has yielded equivocal data on drospirenone and the risk of VTE. The only large prospective study did not show any increase in the risk of VTE; newer studies contain important retrospective data but, by their design, are inherently weaker in regard to their conclusions.

Lastly, database reviews that cannot fully control for confounding and do not include chart review for confirmation of diagnosis do not provide a rationale for avoiding certain CHC formulations, especially if one of those formulations is strongly preferred by your patient.10

Does DMPA lead to HIV?

Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al; Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):19–26.

Much controversy has arisen in recent years over the role of hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition. This led the World Health Organization (WHO) to convene an international meeting of stakeholders earlier this year to address guidelines for hormonal contraception, especially injectables, in women who are living with HIV or are at high risk of acquiring the virus12 (see “What this evidence means for practice” on page 35 for more about this meeting).

Fifteen years ago, a well-designed cohort study showed that female sex workers in Kenya who used depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (sold in the United States as Depo-Provera) for contraception were twice as likely to acquire HIV than sex workers who used a nonhormonal method.13 Since then, numerous published studies on this topic have yielded equivocal results14: for example, the largest one, of 1,536 DMPA users in Uganda and Zimbabwe, showed no increased risk of HIV acquisition with DMPA use.15

In a report of the most recent study, Heffron and coworkers analyzed data from 3,790 serodiscordant couples and found that women who used DMPA were, on average, twice as likely to acquire HIV and to transmit HIV as women who did not use DMPA. The number of seroconversions in the study was, however, low—13 women and 19 men—and investigators did not give information about the duration of DMPA use.

Furthermore, this study was a secondary analysis of a cohort study designed to assess the role of herpes simplex virus in HIV acquisition; it was not designed with the question of a DMPA-HIV link in mind. That leaves questions about contraceptive use, duration of such use, and associated sexual behavior unanswered.

In short, this study adds to an important, growing body of literature, but does not provide evidence for changing gynecologic practice regarding DMPA use and eligibility.

No study has clearly demonstrated sufficiently strong evidence of a putative link between DMPA use and an increased rate of HIV transmission in women at high risk of HIV disease for you to discourage its use in any of your patients for whom DMPA is appropriate.

Stakeholders at the WHO’s 2012 meeting on this matter concluded that 1) no change to guidelines is warranted and 2) hormonal contraception should be promoted for all women, regardless of HIV risk. That conclusion takes into account the fact that the results of more than a decade of research on the role of hormonal contraception in HIV acquisition have been equivocal.12

Given the well-known benefits of effective contraception in preventing unintended pregnancy for all women, especially those at risk of transmitting HIV, you should continue to promote DMPA and all other formulations and methods of hormonal contraception to eligible women.

Click here to find 7 additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management in 2012.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the united states 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38(2):90-6.

2. Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41-50.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States 1900-1999. MMWR. 1999;48(12):241-243.

4. Hubacher D, Finer LB, Espey E. Renewed interest in intrauterine contraception in the United States: evidence and explanation. Contraception. 2011;83(4):291-294.

5. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, Van Vliet HA, Stanwood NL. Immediate post-partum insertion of intrauterine devices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD003036.-

6. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, Hohmann HL, Perriera LK, Creinin MD. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1079-1087.

7. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet. 1995;346(8990):1575-1582.

8. Fuhrmann U, Krattenmacher R, Slater EP, Fritzemeier KH. The novel progestin drospirenone and its natural counterpart progesterone: biochemical profile and antiandrogenic potential. Contraception. 1996;54(4):243-251.

9. Dinger JC, Heinemann LA, Kuhl-Habich D. The safety of a drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive: final results from the European Active Surveillance Study on oral contraceptives based on 142475 women-years of observation. Contraception. 2007;75(5):344-354.

10. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

11. Lidegaard O, Lokkegaard E, Svendsen AL, Agger C. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.-

12. World Health Organization. Hormonal contraception and HIV: a technical statement. 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/Hormonal_contraception_and_HIV.pdf. Accessed June 1 2012.

13. 1Martin HL Jr, Nyange PM, Richardson BA, et al. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(4):1053-1059.

14. Heikinheimo O, Lahteenmaki P. Contraception and HIV infection in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(2):165-176.

15. Morrison CS, Richardson BA, Mmiro F, et al. Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of HIV Acquisition (HC-HIV) Study Group. Hormonal contraception and the risk of HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2007;21(1):85-95.

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene

(and when you should not)

Kari P. Braaten, MD, MPH; Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

The past 20 years have seen an explosion of new contraceptive technologies; women benefit now from a range of effective methods that can satisfy their preferences. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies jumped on board, developing and marketing new hormonal combinations, delivery systems, and inexpensive devices that offer them opportunity for great profit.

Now that many of these newer products have been available for a decade or longer, the combined motivation of women, health-care providers, and industry should have meant better success in preventing undesired pregnancies. Regrettably, we’re moving in the wrong direction: The rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States has increased.

In this Update, we address the sobering reality of the unintended pregnancy rate over 20 years. We then take the opportunity to:

- review new data and guidelines about postpartum and postprocedure insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- explain the latest data and recommendations on venous thrombotic events and combined hormonal methods

- discuss the possibility of an association between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and acquisition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

What are the national data on unintended pregnancy?

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

For decades, we’ve been repeating ourselves about the scope of the problem of unintended pregnancy—namely, “about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended,” etc. The fact that this rate has not improved in nearly 20 years is, in itself, worrisome; despite a proliferation of methods of contraception (and the hope that added options would cause the high rate of unintended pregnancy to fall), an overall benefit hasn’t been realized.

A small, but very important, decrease in the percentage of pregnancies that are unintended—from 49.2% to 48%—occurred between 1994 and 2001.1 New data assembled by Finer and Zolna show, however, that the percentage has crept back up to 49%.

The unintended pregnancy rate is another way to measure this outcome—reflecting the number of unintended pregnancies for every 1,000 women of reproductive age. The lowest rate (44.7) was seen in 1994; by 2006, the rate had increased to 52—just shy of the highest rate of 52.6 that was reported in the early 1980s.

Why haven’t new methods lowered the unintended pregnancy rate?

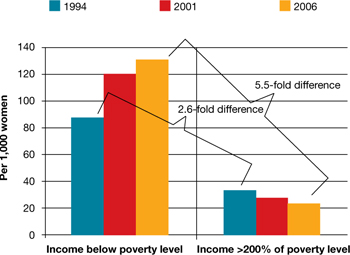

Both unintended pregnancy and abortion affect poorer and younger women disproportionately. In 1994, the unintended pregnancy rate among women who were below the poverty level was 2.6-fold higher than the rate among women who were 200% above the poverty level. That difference in rate increased to 5.5-fold higher by 2006 (FIGURE). The unintended pregnancy rate has increased significantly among poor women while it has continued to decrease among women who are not poor.

The “poverty gap” has been widening in the US rate of unintended pregnancy

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Why has this happened? Perhaps newer contraceptive methods aren’t being used by, or are not available to, women who are most in need. This regrettable trend is a demonstration that unintended pregnancy is a social issue—that there are, without question, “haves” and “have-nots.”

Black women have an unintended pregnancy rate nearly double that of non-Hispanic white women, and are more likely than non-Hispanic white women to opt for an abortion when faced with an unintended pregnancy. New data also show that, from 2005 to 2008, the number of abortions and the abortion rate in the United States have remained approximately the same.2 While the rate of unintended pregnancy increases, therefore, principally among poor women, more of those pregnancies are being continued.

Contraception, recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most important public health advances of the past century, is not having a maximal impact in the United States.3 The primary goal of contraception is to prevent unintended pregnancy; we have not continued to make strides in the last two decades against the unintended pregnancy rate so that women control when they have children and how many they have.

Advertising for contraceptives cannot take the place of education by physicians. Your care of reproductive-age women should include finding an opportunity, at every visit, to address, and educate them on, contraception.

Even more important, primary care physicians—whose ability to offer such highly effective options as IUDs, implants, and sterilization might be limited—need to be better educated to ensure that they 1) provide contraceptive counseling to women and 2) refer patients to a gynecologist or a trained primary care provider who can offer them access to the most appropriate of the full range of methods.

A final note: Continued advocacy of contraception as an important component of primary preventive medicine by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) should mean better support for seasoned providers and new trainees to give contraception and family planning the clinical attention it needs.

More evidence on postpregnancy IUD placement

Bednarek PH, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Cwiak C, Espey E, Jensen JT; Post-Aspiration IUD Randomization (PAIR) Study Trial Group. Immediate versus delayed IUD insertion after uterine aspiration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2208–2217.

Cremer M, Bullard KA, Mosley RM, et al. Immediate vs. delayed post-abortal copper T 380A IUD insertion in cases over 12 weeks of gestation. Contraception. 2011;83(6):522–527.

Hohmann HL, Reeves MF, Chen BA, Perriera LK, Hayes JL, Creinin MD. Immediate versus delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device following dilation and evacuation: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2012;85(3):240–245.

Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, Rosario L, Westhoff C. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):623–628.

Betstadt SJ, Turok DK, Kapp N, Feng KT, Borgatta L. Intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Contraception. 2011;83(6):517–521.

Celen S, Sucak A, Yildiz Y, Danisman N. Immediate postplacental insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device during cesarean section. Contraception. 2011;84(3):240–243.

Intrauterine devices have received a great deal of attention in recent years. Indeed, the utilization rate has increased significantly, with 5.5% of contraceptive users—2.1 million women—now using an IUD.4 Although most women who use an IUD obtain it at an outpatient office, remote from pregnancy and where the safety profile and risk of expulsion are well documented, many women who desire effective contraception like an IUD may not be seen by a provider until they are pregnant.

A significant body of data has been published recently on the role of postpregnancy IUD placement, adding important information to the existing body of literature.

Multicenter randomized trial. A study in the United States by Bednarek and co-workers demonstrated that immediate post-aspiration placement of an IUD resulted in a higher rate (>90%) of IUD utilization at 6 months than did insertion 6 to 8 weeks postpartum (just above 75%). Furthermore, five pregnancies were documented in the group with delayed IUD insertion; none were seen in the immediate-insertion group.

Independent randomized trials. Two studies (by Cremer and colleagues and Hohmann and colleagues) showed that immediate post-dilation and evacuation placement of an IUD also yielded a significantly higher rate of continued usage at 6 months than did delayed placement. (The terms “postaspiration” and “post–dilation and evacuation” are important as they encompass elective termination procedures for miscarriage management and fetal demise among women who may have undesired fertility.) For women having such procedures who do not want another pregnancy in the near future, immediate provision of highly effective contraception can best be performed at the time of the procedure.

New data: Use of IUD after medical abortion. A randomized trial conducted by Shimoni and colleagues showed 1) no significant difference in expulsion after immediate versus delayed placement and 2) several pregnancies in the delayed group. Regrettably, the investigators did not clearly define “immediate placement.”

In another prospective cohort study, Betstadt and coworkers reported a low rate of expulsion (4.1%) when an IUD was placed within 14 days after confirmed medical abortion. The findings of that study were also limited because the researchers followed women for only 3 months after the IUD was placed.

These new studies shed important light on the safety and tolerability of immediate IUD insertion. More questions remain, however, about ideal timing of placement after medical abortion. Postpartum IUDs have also been promoted as an important method of effective contraception despite higher expulsion rates than interval insertion, which must be compared to the high rate of loss to follow-up.5

Prospective cohort study. A well-designed study recently addressed outcomes of post-placental IUD placement during cesarean delivery. Celen and colleagues followed 245 women for longer than 1 year after postplacental copper-T IUD placement and reported a 17% cumulative expulsion rate and an overall continuation rate of 62%. These rates are not significantly lower than the cumulative expulsion rate and overall continuation rate associated with postplacental insertion after vaginal delivery. The investigators also reported no increased risk of serious complications, infection, or perforation with postplacental IUD placement after cesarean delivery.

The necessity of coming to clinic in the months right after the end of a pregnancy to obtain highly effective contraception is, for women who are in this position, a well-established barrier to ensuring that they receive the protection they want. We now have important data showing that IUD placement after suction aspiration, dilation and evacuation, cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery6 is effective and causes minimal side effects.

Better data are needed before we can make a universal recommendation about inserting an IUD shortly after medical abortion.

Overall, you should consider that the reversibility and known safety profile of an IUD continue to make this device an ideal contraceptive for many women.

VTE risk, postpartum hormonal contraception, and progestin type

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010: Revised recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(26):878–883.

Lidegaard O, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, Skjeldestad FE, Lokkegaard E. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001–9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC) increases a woman’s risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), an effect that has been attributed to the thrombogenic effects of estrogen.7 The combined risk of VTE from CHC and the known independent risk of VTE postpartum has prompted the CDC to recommend against the use of any combined (i.e., estrogen-containing) method for 21 days postpartum. Although no direct evidence exists of a higher rate of VTE with CHC immediately postpartum, indirect evidence of increased risk should be considered very seriously.

Evidence from retrospective and database studies continues to suggest that one of the newer progestins, drospirenone, may play a larger role in VTE than previously understood, reigniting the debate over the risk of VTE and combined oral contraceptives (OCs).

Drospirenone was introduced in 2001 in combination with ethinyl estradiol in an OC that had the added benefits of alleviating acne and controlling premenstrual symptoms.8 A large (142,475 woman-years) prospective trial examining the role of drospirenone showed no significant difference between this hormone and other forms of progesterone in regard to adverse cardiovascular events.9 This study had minimal loss to follow-up (2.4%) and is the only cohort to confirm VTE outcomes based on medical records review (rather than insurance claims databases or national registries).10

A national cohort study in Denmark, published in 2009, found that the risk of VTE was directly related to duration of use and the dosage of estrogen.11 More significantly, those investigators found that specific progestin types, including drospirenone, desogestrel, and gestodene, were also associated with increased VTE risk.

Danish researchers conducted another retrospective study to assess the VTE risk associated with drospirenone in CHC—a review that included other progestins, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, and progestin-only pills. The results again suggested that contraceptives that contain drospirenone, desogestrel, or gestodene were associated with more than twice the risk of VTE, compared with OCs that contain levonorgestrel.

For gestodene and desogestrel, increasing the dosage of estrogen increased the risk of VTE; for drospirenone, however, the dosage of estrogen did not affect the rate of VTE. No association was found between the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD or progestin-only pills with VTE. Overall, the absolute number of VTE was small (4,307 VTE among 1.3 million women using hormonal contraception), which is reassuring, considering that this was a large cohort study.

No combination hormonal contraception (CHC) of any type should be prescribed for use during the 3 weeks after delivery, given indirect evidence of increased risk of VTE during this period and the known VTE risk posed by CHC.

For women who are beyond that window and who want CHC, the question becomes: How should you counsel them about progestins in different formulations?

A decade of research has yielded equivocal data on drospirenone and the risk of VTE. The only large prospective study did not show any increase in the risk of VTE; newer studies contain important retrospective data but, by their design, are inherently weaker in regard to their conclusions.

Lastly, database reviews that cannot fully control for confounding and do not include chart review for confirmation of diagnosis do not provide a rationale for avoiding certain CHC formulations, especially if one of those formulations is strongly preferred by your patient.10

Does DMPA lead to HIV?

Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al; Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):19–26.

Much controversy has arisen in recent years over the role of hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition. This led the World Health Organization (WHO) to convene an international meeting of stakeholders earlier this year to address guidelines for hormonal contraception, especially injectables, in women who are living with HIV or are at high risk of acquiring the virus12 (see “What this evidence means for practice” on page 35 for more about this meeting).

Fifteen years ago, a well-designed cohort study showed that female sex workers in Kenya who used depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (sold in the United States as Depo-Provera) for contraception were twice as likely to acquire HIV than sex workers who used a nonhormonal method.13 Since then, numerous published studies on this topic have yielded equivocal results14: for example, the largest one, of 1,536 DMPA users in Uganda and Zimbabwe, showed no increased risk of HIV acquisition with DMPA use.15

In a report of the most recent study, Heffron and coworkers analyzed data from 3,790 serodiscordant couples and found that women who used DMPA were, on average, twice as likely to acquire HIV and to transmit HIV as women who did not use DMPA. The number of seroconversions in the study was, however, low—13 women and 19 men—and investigators did not give information about the duration of DMPA use.

Furthermore, this study was a secondary analysis of a cohort study designed to assess the role of herpes simplex virus in HIV acquisition; it was not designed with the question of a DMPA-HIV link in mind. That leaves questions about contraceptive use, duration of such use, and associated sexual behavior unanswered.

In short, this study adds to an important, growing body of literature, but does not provide evidence for changing gynecologic practice regarding DMPA use and eligibility.

No study has clearly demonstrated sufficiently strong evidence of a putative link between DMPA use and an increased rate of HIV transmission in women at high risk of HIV disease for you to discourage its use in any of your patients for whom DMPA is appropriate.

Stakeholders at the WHO’s 2012 meeting on this matter concluded that 1) no change to guidelines is warranted and 2) hormonal contraception should be promoted for all women, regardless of HIV risk. That conclusion takes into account the fact that the results of more than a decade of research on the role of hormonal contraception in HIV acquisition have been equivocal.12

Given the well-known benefits of effective contraception in preventing unintended pregnancy for all women, especially those at risk of transmitting HIV, you should continue to promote DMPA and all other formulations and methods of hormonal contraception to eligible women.

Click here to find 7 additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management in 2012.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene

(and when you should not)

Kari P. Braaten, MD, MPH; Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

The past 20 years have seen an explosion of new contraceptive technologies; women benefit now from a range of effective methods that can satisfy their preferences. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies jumped on board, developing and marketing new hormonal combinations, delivery systems, and inexpensive devices that offer them opportunity for great profit.

Now that many of these newer products have been available for a decade or longer, the combined motivation of women, health-care providers, and industry should have meant better success in preventing undesired pregnancies. Regrettably, we’re moving in the wrong direction: The rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States has increased.

In this Update, we address the sobering reality of the unintended pregnancy rate over 20 years. We then take the opportunity to:

- review new data and guidelines about postpartum and postprocedure insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- explain the latest data and recommendations on venous thrombotic events and combined hormonal methods

- discuss the possibility of an association between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and acquisition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

What are the national data on unintended pregnancy?

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

For decades, we’ve been repeating ourselves about the scope of the problem of unintended pregnancy—namely, “about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended,” etc. The fact that this rate has not improved in nearly 20 years is, in itself, worrisome; despite a proliferation of methods of contraception (and the hope that added options would cause the high rate of unintended pregnancy to fall), an overall benefit hasn’t been realized.

A small, but very important, decrease in the percentage of pregnancies that are unintended—from 49.2% to 48%—occurred between 1994 and 2001.1 New data assembled by Finer and Zolna show, however, that the percentage has crept back up to 49%.

The unintended pregnancy rate is another way to measure this outcome—reflecting the number of unintended pregnancies for every 1,000 women of reproductive age. The lowest rate (44.7) was seen in 1994; by 2006, the rate had increased to 52—just shy of the highest rate of 52.6 that was reported in the early 1980s.

Why haven’t new methods lowered the unintended pregnancy rate?

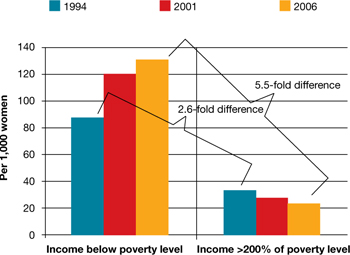

Both unintended pregnancy and abortion affect poorer and younger women disproportionately. In 1994, the unintended pregnancy rate among women who were below the poverty level was 2.6-fold higher than the rate among women who were 200% above the poverty level. That difference in rate increased to 5.5-fold higher by 2006 (FIGURE). The unintended pregnancy rate has increased significantly among poor women while it has continued to decrease among women who are not poor.

The “poverty gap” has been widening in the US rate of unintended pregnancy

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Why has this happened? Perhaps newer contraceptive methods aren’t being used by, or are not available to, women who are most in need. This regrettable trend is a demonstration that unintended pregnancy is a social issue—that there are, without question, “haves” and “have-nots.”

Black women have an unintended pregnancy rate nearly double that of non-Hispanic white women, and are more likely than non-Hispanic white women to opt for an abortion when faced with an unintended pregnancy. New data also show that, from 2005 to 2008, the number of abortions and the abortion rate in the United States have remained approximately the same.2 While the rate of unintended pregnancy increases, therefore, principally among poor women, more of those pregnancies are being continued.

Contraception, recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most important public health advances of the past century, is not having a maximal impact in the United States.3 The primary goal of contraception is to prevent unintended pregnancy; we have not continued to make strides in the last two decades against the unintended pregnancy rate so that women control when they have children and how many they have.

Advertising for contraceptives cannot take the place of education by physicians. Your care of reproductive-age women should include finding an opportunity, at every visit, to address, and educate them on, contraception.

Even more important, primary care physicians—whose ability to offer such highly effective options as IUDs, implants, and sterilization might be limited—need to be better educated to ensure that they 1) provide contraceptive counseling to women and 2) refer patients to a gynecologist or a trained primary care provider who can offer them access to the most appropriate of the full range of methods.

A final note: Continued advocacy of contraception as an important component of primary preventive medicine by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) should mean better support for seasoned providers and new trainees to give contraception and family planning the clinical attention it needs.

More evidence on postpregnancy IUD placement

Bednarek PH, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Cwiak C, Espey E, Jensen JT; Post-Aspiration IUD Randomization (PAIR) Study Trial Group. Immediate versus delayed IUD insertion after uterine aspiration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2208–2217.

Cremer M, Bullard KA, Mosley RM, et al. Immediate vs. delayed post-abortal copper T 380A IUD insertion in cases over 12 weeks of gestation. Contraception. 2011;83(6):522–527.

Hohmann HL, Reeves MF, Chen BA, Perriera LK, Hayes JL, Creinin MD. Immediate versus delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device following dilation and evacuation: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2012;85(3):240–245.

Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, Rosario L, Westhoff C. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):623–628.

Betstadt SJ, Turok DK, Kapp N, Feng KT, Borgatta L. Intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Contraception. 2011;83(6):517–521.

Celen S, Sucak A, Yildiz Y, Danisman N. Immediate postplacental insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device during cesarean section. Contraception. 2011;84(3):240–243.

Intrauterine devices have received a great deal of attention in recent years. Indeed, the utilization rate has increased significantly, with 5.5% of contraceptive users—2.1 million women—now using an IUD.4 Although most women who use an IUD obtain it at an outpatient office, remote from pregnancy and where the safety profile and risk of expulsion are well documented, many women who desire effective contraception like an IUD may not be seen by a provider until they are pregnant.

A significant body of data has been published recently on the role of postpregnancy IUD placement, adding important information to the existing body of literature.

Multicenter randomized trial. A study in the United States by Bednarek and co-workers demonstrated that immediate post-aspiration placement of an IUD resulted in a higher rate (>90%) of IUD utilization at 6 months than did insertion 6 to 8 weeks postpartum (just above 75%). Furthermore, five pregnancies were documented in the group with delayed IUD insertion; none were seen in the immediate-insertion group.

Independent randomized trials. Two studies (by Cremer and colleagues and Hohmann and colleagues) showed that immediate post-dilation and evacuation placement of an IUD also yielded a significantly higher rate of continued usage at 6 months than did delayed placement. (The terms “postaspiration” and “post–dilation and evacuation” are important as they encompass elective termination procedures for miscarriage management and fetal demise among women who may have undesired fertility.) For women having such procedures who do not want another pregnancy in the near future, immediate provision of highly effective contraception can best be performed at the time of the procedure.

New data: Use of IUD after medical abortion. A randomized trial conducted by Shimoni and colleagues showed 1) no significant difference in expulsion after immediate versus delayed placement and 2) several pregnancies in the delayed group. Regrettably, the investigators did not clearly define “immediate placement.”

In another prospective cohort study, Betstadt and coworkers reported a low rate of expulsion (4.1%) when an IUD was placed within 14 days after confirmed medical abortion. The findings of that study were also limited because the researchers followed women for only 3 months after the IUD was placed.

These new studies shed important light on the safety and tolerability of immediate IUD insertion. More questions remain, however, about ideal timing of placement after medical abortion. Postpartum IUDs have also been promoted as an important method of effective contraception despite higher expulsion rates than interval insertion, which must be compared to the high rate of loss to follow-up.5

Prospective cohort study. A well-designed study recently addressed outcomes of post-placental IUD placement during cesarean delivery. Celen and colleagues followed 245 women for longer than 1 year after postplacental copper-T IUD placement and reported a 17% cumulative expulsion rate and an overall continuation rate of 62%. These rates are not significantly lower than the cumulative expulsion rate and overall continuation rate associated with postplacental insertion after vaginal delivery. The investigators also reported no increased risk of serious complications, infection, or perforation with postplacental IUD placement after cesarean delivery.

The necessity of coming to clinic in the months right after the end of a pregnancy to obtain highly effective contraception is, for women who are in this position, a well-established barrier to ensuring that they receive the protection they want. We now have important data showing that IUD placement after suction aspiration, dilation and evacuation, cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery6 is effective and causes minimal side effects.

Better data are needed before we can make a universal recommendation about inserting an IUD shortly after medical abortion.

Overall, you should consider that the reversibility and known safety profile of an IUD continue to make this device an ideal contraceptive for many women.

VTE risk, postpartum hormonal contraception, and progestin type

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010: Revised recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(26):878–883.

Lidegaard O, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, Skjeldestad FE, Lokkegaard E. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001–9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC) increases a woman’s risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), an effect that has been attributed to the thrombogenic effects of estrogen.7 The combined risk of VTE from CHC and the known independent risk of VTE postpartum has prompted the CDC to recommend against the use of any combined (i.e., estrogen-containing) method for 21 days postpartum. Although no direct evidence exists of a higher rate of VTE with CHC immediately postpartum, indirect evidence of increased risk should be considered very seriously.

Evidence from retrospective and database studies continues to suggest that one of the newer progestins, drospirenone, may play a larger role in VTE than previously understood, reigniting the debate over the risk of VTE and combined oral contraceptives (OCs).

Drospirenone was introduced in 2001 in combination with ethinyl estradiol in an OC that had the added benefits of alleviating acne and controlling premenstrual symptoms.8 A large (142,475 woman-years) prospective trial examining the role of drospirenone showed no significant difference between this hormone and other forms of progesterone in regard to adverse cardiovascular events.9 This study had minimal loss to follow-up (2.4%) and is the only cohort to confirm VTE outcomes based on medical records review (rather than insurance claims databases or national registries).10

A national cohort study in Denmark, published in 2009, found that the risk of VTE was directly related to duration of use and the dosage of estrogen.11 More significantly, those investigators found that specific progestin types, including drospirenone, desogestrel, and gestodene, were also associated with increased VTE risk.

Danish researchers conducted another retrospective study to assess the VTE risk associated with drospirenone in CHC—a review that included other progestins, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, and progestin-only pills. The results again suggested that contraceptives that contain drospirenone, desogestrel, or gestodene were associated with more than twice the risk of VTE, compared with OCs that contain levonorgestrel.

For gestodene and desogestrel, increasing the dosage of estrogen increased the risk of VTE; for drospirenone, however, the dosage of estrogen did not affect the rate of VTE. No association was found between the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD or progestin-only pills with VTE. Overall, the absolute number of VTE was small (4,307 VTE among 1.3 million women using hormonal contraception), which is reassuring, considering that this was a large cohort study.

No combination hormonal contraception (CHC) of any type should be prescribed for use during the 3 weeks after delivery, given indirect evidence of increased risk of VTE during this period and the known VTE risk posed by CHC.

For women who are beyond that window and who want CHC, the question becomes: How should you counsel them about progestins in different formulations?

A decade of research has yielded equivocal data on drospirenone and the risk of VTE. The only large prospective study did not show any increase in the risk of VTE; newer studies contain important retrospective data but, by their design, are inherently weaker in regard to their conclusions.

Lastly, database reviews that cannot fully control for confounding and do not include chart review for confirmation of diagnosis do not provide a rationale for avoiding certain CHC formulations, especially if one of those formulations is strongly preferred by your patient.10

Does DMPA lead to HIV?

Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al; Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):19–26.

Much controversy has arisen in recent years over the role of hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition. This led the World Health Organization (WHO) to convene an international meeting of stakeholders earlier this year to address guidelines for hormonal contraception, especially injectables, in women who are living with HIV or are at high risk of acquiring the virus12 (see “What this evidence means for practice” on page 35 for more about this meeting).

Fifteen years ago, a well-designed cohort study showed that female sex workers in Kenya who used depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (sold in the United States as Depo-Provera) for contraception were twice as likely to acquire HIV than sex workers who used a nonhormonal method.13 Since then, numerous published studies on this topic have yielded equivocal results14: for example, the largest one, of 1,536 DMPA users in Uganda and Zimbabwe, showed no increased risk of HIV acquisition with DMPA use.15

In a report of the most recent study, Heffron and coworkers analyzed data from 3,790 serodiscordant couples and found that women who used DMPA were, on average, twice as likely to acquire HIV and to transmit HIV as women who did not use DMPA. The number of seroconversions in the study was, however, low—13 women and 19 men—and investigators did not give information about the duration of DMPA use.

Furthermore, this study was a secondary analysis of a cohort study designed to assess the role of herpes simplex virus in HIV acquisition; it was not designed with the question of a DMPA-HIV link in mind. That leaves questions about contraceptive use, duration of such use, and associated sexual behavior unanswered.

In short, this study adds to an important, growing body of literature, but does not provide evidence for changing gynecologic practice regarding DMPA use and eligibility.

No study has clearly demonstrated sufficiently strong evidence of a putative link between DMPA use and an increased rate of HIV transmission in women at high risk of HIV disease for you to discourage its use in any of your patients for whom DMPA is appropriate.

Stakeholders at the WHO’s 2012 meeting on this matter concluded that 1) no change to guidelines is warranted and 2) hormonal contraception should be promoted for all women, regardless of HIV risk. That conclusion takes into account the fact that the results of more than a decade of research on the role of hormonal contraception in HIV acquisition have been equivocal.12

Given the well-known benefits of effective contraception in preventing unintended pregnancy for all women, especially those at risk of transmitting HIV, you should continue to promote DMPA and all other formulations and methods of hormonal contraception to eligible women.

Click here to find 7 additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management in 2012.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the united states 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38(2):90-6.

2. Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41-50.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States 1900-1999. MMWR. 1999;48(12):241-243.

4. Hubacher D, Finer LB, Espey E. Renewed interest in intrauterine contraception in the United States: evidence and explanation. Contraception. 2011;83(4):291-294.

5. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, Van Vliet HA, Stanwood NL. Immediate post-partum insertion of intrauterine devices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD003036.-

6. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, Hohmann HL, Perriera LK, Creinin MD. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1079-1087.

7. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet. 1995;346(8990):1575-1582.

8. Fuhrmann U, Krattenmacher R, Slater EP, Fritzemeier KH. The novel progestin drospirenone and its natural counterpart progesterone: biochemical profile and antiandrogenic potential. Contraception. 1996;54(4):243-251.

9. Dinger JC, Heinemann LA, Kuhl-Habich D. The safety of a drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive: final results from the European Active Surveillance Study on oral contraceptives based on 142475 women-years of observation. Contraception. 2007;75(5):344-354.

10. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

11. Lidegaard O, Lokkegaard E, Svendsen AL, Agger C. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.-

12. World Health Organization. Hormonal contraception and HIV: a technical statement. 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/Hormonal_contraception_and_HIV.pdf. Accessed June 1 2012.

13. 1Martin HL Jr, Nyange PM, Richardson BA, et al. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(4):1053-1059.

14. Heikinheimo O, Lahteenmaki P. Contraception and HIV infection in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(2):165-176.

15. Morrison CS, Richardson BA, Mmiro F, et al. Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of HIV Acquisition (HC-HIV) Study Group. Hormonal contraception and the risk of HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2007;21(1):85-95.

1. Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the united states 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38(2):90-6.

2. Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41-50.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States 1900-1999. MMWR. 1999;48(12):241-243.

4. Hubacher D, Finer LB, Espey E. Renewed interest in intrauterine contraception in the United States: evidence and explanation. Contraception. 2011;83(4):291-294.

5. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, Van Vliet HA, Stanwood NL. Immediate post-partum insertion of intrauterine devices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD003036.-

6. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, Hohmann HL, Perriera LK, Creinin MD. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1079-1087.

7. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet. 1995;346(8990):1575-1582.

8. Fuhrmann U, Krattenmacher R, Slater EP, Fritzemeier KH. The novel progestin drospirenone and its natural counterpart progesterone: biochemical profile and antiandrogenic potential. Contraception. 1996;54(4):243-251.

9. Dinger JC, Heinemann LA, Kuhl-Habich D. The safety of a drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive: final results from the European Active Surveillance Study on oral contraceptives based on 142475 women-years of observation. Contraception. 2007;75(5):344-354.

10. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

11. Lidegaard O, Lokkegaard E, Svendsen AL, Agger C. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.-

12. World Health Organization. Hormonal contraception and HIV: a technical statement. 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/Hormonal_contraception_and_HIV.pdf. Accessed June 1 2012.

13. 1Martin HL Jr, Nyange PM, Richardson BA, et al. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(4):1053-1059.

14. Heikinheimo O, Lahteenmaki P. Contraception and HIV infection in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(2):165-176.

15. Morrison CS, Richardson BA, Mmiro F, et al. Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of HIV Acquisition (HC-HIV) Study Group. Hormonal contraception and the risk of HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2007;21(1):85-95.