User login

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

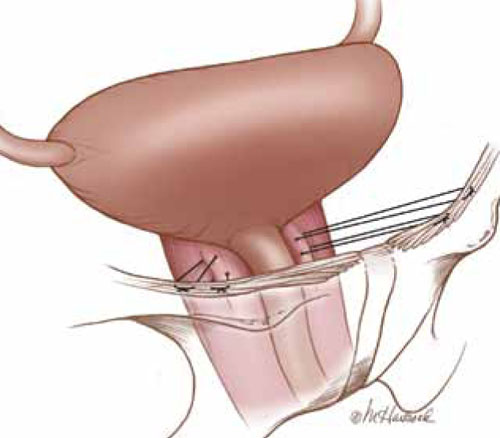

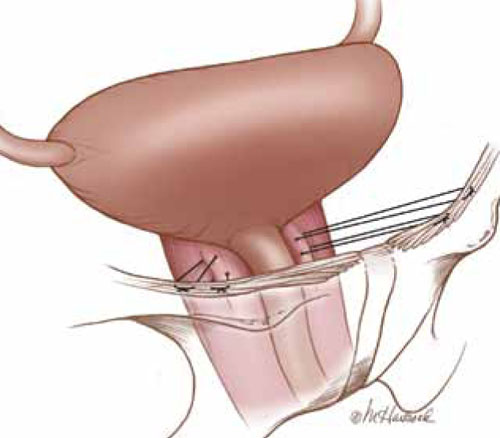

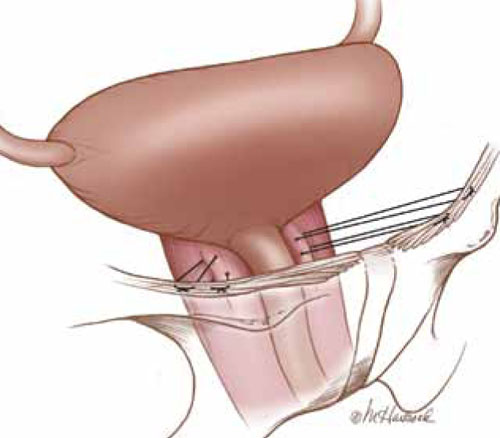

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.