User login

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Patients today often are overfed but undernourished. A growing body of literature links dietary choices to brain health and the risk of psychiatric illness. Vitamin deficiencies can affect psychiatric patients in several ways:

- deficiencies may play a causative role in mental illness and exacerbate symptoms

- psychiatric symptoms can result in poor nutrition

- vitamin insufficiency—defined as subclinical deficiency—may compromise patient recovery.

Additionally, genetic differences may compromise vitamin and essential nutrient pathways.

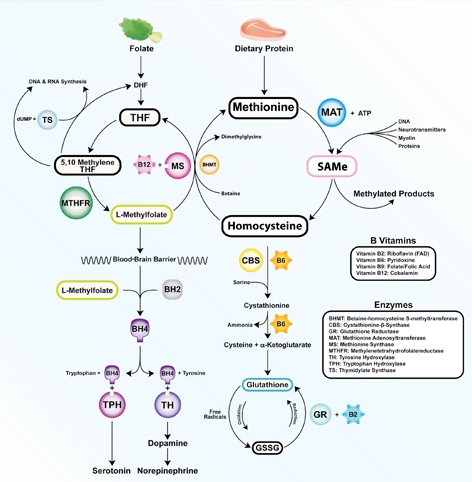

Vitamins are dietary components other than carbohydrates, fats, minerals, and proteins that are necessary for life. B vitamins are required for proper functioning of the methylation cycle, monoamine production, DNA synthesis, and maintenance of phospholipids such as myelin (Figure). Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E play important roles in genetic transcription, antioxidant recycling, and inflammatory regulation in the brain.

Figure: The methylation cycle

Vitamins B2, B6, B9, and B12 directly impact the functioning of the methylation cycle. Deficiencies pertain to brain function, as neurotransmitters, myelin, and active glutathione are dependent on one-carbon metabolism

Illustration: Mala Nimalasuriya with permission from DrewRamseyMD.com

To help clinicians recognize and treat vitamin deficiencies among psychiatric patients, this article reviews the role of the 6 essential water-soluble vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and C; Table 1,1) and 3 fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, and E; Table 2,1) in brain metabolism and psychiatric pathology. Because numerous sources address using supplements to treat vitamin deficiencies, this article emphasizes food sources, which for many patients are adequate to sustain nutrient status.

Table 1

Water-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (thiamine): Glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle | ||||

| Rare; 7% in heart failure patients | 5% total, 12% of older women | Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, memory impairment, confusion, lack of coordination, paralysis | Older adults, malabsorptive conditions, heavy alcohol use. Those with diabetes are at risk because of increased clearance | Pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ. Raw fish, tea, and betel nuts impair absorption |

| B2 (riboflavin): FMN, FAD cofactors in glycolysis and oxidative pathways. B6, folate, and glutathione synthesis | ||||

| 10% to 27% of older adults | <3%; 95% of adolescent girls (measured by EGRAC) | Fatigue, cracked lips, sore throat, bloodshot eyes | Older adults, low intake of animal and dairy products, heavy alcohol use | Dairy, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes |

| B6 (pyridoxal): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 11% to 24% (<5 ng/mL); 38% of heart failure patients | 14% total, 26% of adults | Dermatitis, glossitis, convulsions, migraine, chronic pain, depression | Older adults, women who use oral contraceptives, alcoholism. 33% to 49% of women age >51 have inadequate intake | Bananas, beans, potatoes, navy beans, salmon, steak, and whole grains |

| B9 (folate): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 0.5% total; up to 50% of depressed patients | 16% of adults, 19% of adolescent girls | Loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, heart palpitations, behavioral disorders | Depression, pregnancy and lactation, alcoholism, dialysis, liver disease. Deficiency during pregnancy is linked to neural tube defects | Leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans, and peas |

| B12 (cobalamin): Methylation cycle (cofactor methionine synthase) | ||||

| 10% to 15% of older adults | <3% to 9% | Depression, irritability, anemia, fatigue, shortness of breath, high blood pressure | Vegetarian or vegan diet, achlorhydria, older adults. Deficiency more often due to poor absorption than low consumption | Meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy |

| C (ascorbic acid): Antioxidant | ||||

| 7.1% | 31% | Scurvy, fatigue, anemia, joint pain, petechia. Symptoms develop after 1 to 3 months of no dietary intake | Smokers, infants fed boiled or evaporated milk, limited dietary variation, patients with malabsorption, chronic illnesses | Citrus fruits, tomatoes and tomato juice, and potatoes |

| EGRAC: erythrocyte glutathione reductase activation coefficient; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide; FMN: flavin mononucleotide Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Table 2

Fat-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (retinol): Transcription regulation, vision | ||||

| <5% of U.S. population | 44% | Blindness, decreased immunity, corneal and retinal damage | Pregnant women, individuals with strict dietary restrictions, heavy alcohol use, chronic diarrhea, fat malabsorptive conditions | Beef liver, dairy products. Convertible beta-carotene sources: sweet potatoes, carrots, spinach, butternut squash, greens, broccoli, cantaloupe |

| D (cholecalciferol): Hormone, transcriptional regulation | ||||

| ≥50%, 90% of adults age >50 | 69% | Rickets, osteoporosis, muscle twitching | Breast-fed infants, older adults, limited sun exposure, pigmented skin, fat malabsorption, obesity. Older adults have an impaired ability to make vitamin D from the sun. SPF 15 reduces production by 99% | Fatty fish and fish liver oils, sun-dried mushrooms |

| E (tocopherols and tocotrienols): Antioxidant, PUFA protectant, gene regulation | ||||

| Rare | 93% | Anemia, neuropathy, myopathy, abnormal eye movements, weakness, retinal damage | Malabsorptive conditions, HIV, depression | Sunflower, wheat germ, and safflower oils; meats; fish; dairy; green vegetables |

| HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; SPF: sun protection factor Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Water-soluble vitamins

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is essential for glucose metabolism. Pregnancy, lactation, and fever increase the need for thiamine, and tea, coffee, and shellfish can impair its absorption. Although rare, severe B1 deficiency can lead to beriberi, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ataxia, nystagmus), and Korsakoff’s psychosis (confabulation, lack of insight, retrograde and anterograde amnesia, and apathy). Confusion and disorientation stem from the brain’s inability to oxidize glucose for energy because B1 is a critical cofactor in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Deficiency leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory cytokines, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction.2 Wernicke’s encephalopathy is most frequently encountered in patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetes, or eating disorders, and after bariatric surgery.3 Iatrogenic Wernicke’s encephalopathy may occur when depleted patients receive IV saline with dextrose without receiving thiamine. Top dietary sources of B1 include pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ.

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is essential for oxidative pathways, monoamine synthesis, and the methylation cycle. B2 is needed to create the essential flavoprotein coenzymes for synthesis of L-methylfolate—the active form of folate—and for proper utilization of B6. Deficiency can occur after 4 months of inadequate intake.

Although generally B2 deficiency is rare, surveys in the United States have found that 10% to 27% of older adults (age ≥65) are deficient.4 Low intake of dairy products and meat and chronic, excessive alcohol intake are associated with deficiency. Marginal B2 levels are more prevalent in depressed patients, possibly because of B2’s role in the function of glutathione, an endogenous antioxidant.5 Top dietary sources of B2 are dairy products, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes.

Vitamin B6 refers to 3 distinct compounds: pyridoxine, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine. B6 is essential to glycolysis, the methylation cycle, and recharging glutathione, an innate antioxidant in the brain. Higher levels of vitamin B6 are associated with a lower prevalence of depression in adolescents,6 and low dietary and plasma B6 increases the risk and severity of depression in geriatric patients7 and predicts depression in prospective trials.8 Deficiency is common (24% to 56%) among patients receiving hemodialysis.9 Women who take oral contraceptives are at increased risk of vitamin B6 deficiency.10 Top dietary sources are fish, beef, poultry, potatoes, legumes, and spinach.

Vitamin B9 (folate) is needed for proper one-carbon metabolism and thus requisite in synthesis of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and DNA and in phospholipid production. Low maternal folate status increases the risk of neural tube defects in newborns. Folate deficiency and insufficiency are common among patients with mood disorders and correlate with illness severity.11 In a study of 2,682 Finnish men, those in the lowest one-third of folate consumption had a 67% increased relative risk of depression.12 A meta-analysis of 11 studies of 15,315 persons found those who had low folate levels had a significant risk of depression.13 Patients without deficiency but with folate levels near the low end of the normal range also report low mood.14 Compared with controls, patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis have lower levels of folate, B12, and docosahexaenoic acid.15

Dietary folate must be converted to L-methylfolate for use in the brain. Patients with a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism produce a less active form of the enzyme. The TT genotype is associated with major depression and bipolar disorder.16 Clinical trials have shown that several forms of folate can enhance antidepressant treatment.17 Augmentation with L-methylfolate, which bypasses the MTHFR enzyme, can be an effective strategy for treating depression in these patients.18

Leafy greens and legumes such as lentils are top dietary sources of folate; supplemental folic acid has been linked to an increased risk of cancer and overall mortality.19,20

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin). An essential cofactor in one-carbon metabolism, B12 is needed to produce monoamine neurotransmitters and maintain myelin. Deficiency is found in up to one-third of depressed patients11 and compromises antidepressant response,21 whereas higher vitamin B12 levels are associated with better treatment outcomes.22 B12 deficiency can cause depression, irritability, agitation, psychosis, and obsessive symptoms.23,24 Low B12 levels and elevated homocysteine increase the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and are linked to a 5-fold increase in the rate of brain atrophy.26

B12 deficiencies may be seen in patients with gastrointestinal illness, older adults with achlorhydria, and vegans and vegetarians, in whom B12 intake can be low. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole interfere with B12 absorption from food.

Psychiatric symptoms of B12 deficiency may present before hematologic findings.23 Folic acid supplementation may mask a B12 deficiency by delaying anemia but will not delay psychiatric symptoms. Ten percent of patients with an insufficiency (low normal levels of 200 to 400 pg/mL) have elevated homocysteine, which increases the risk of psychiatric disorders as well as comorbid illnesses such as cardiovascular disease. Top dietary sources include fish, mollusks (oysters, mussels, and clams), meat, and dairy products.

Vitamin C is vital for the synthesis of monoamines such as serotonin and norepinephrine. Vitamin C’s primary role in the brain is as an antioxidant. As a necessary cofactor, it keeps the copper and iron in metalloenzymes reduced, and also recycles vitamin E. Proper function of the methylation cycle depends on vitamin C, as does collagen synthesis and metabolism of xenobiotics by the liver. It is concentrated in cerebrospinal fluid.

Humans cannot manufacture vitamin C. Although the need for vitamin C (90 mg/d) is thought to be met by diet, studies have found that up to 13.7% of healthy, middle class patients in the United States are depleted.27 Older adults and patients with a poor diet due to drug or alcohol abuse, eating disorders, or affective symptoms are at risk.

Scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency and leads to bleeding gums and petechiae. Patients with insufficiency report irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, and hypochondriasis. Vitamin C intake is significantly lower in older adults (age ≥60) with depression.28 Some research indicates patients with schizophrenia have decreased vitamin C levels and dysfunction of antioxidant defenses.29 Citrus, potatoes, and tomatoes are top dietary sources of vitamin C.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A. Although vitamin A activity in the brain is poorly understood, retinol—the active form of vitamin A—is crucial for formation of opsins, which are the basis for vision. Childhood vitamin A deficiency may lead to blindness. Vitamin A also plays an important role in maintaining bone growth, reproduction, cell division, and immune system integrity.30 Animal sources such as beef liver, dairy products, and eggs provide retinol, and plant sources such as carrots, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens provide provitamin A carotenoids that humans convert into retinol.

Deficiency rarely is observed in the United States but remains a common problem for developing nations. In the United States, vitamin A deficiency is most often seen with excessive alcohol use, rigorous dietary restrictions, and gastrointestinal diseases accompanied by poor fat absorption.

Excess vitamin A ingestion may result in bone abnormalities, liver damage, birth defects, and depression. Isotretinoin—a form of vitamin A used to treat severe acne—carries an FDA “black-box” warning for psychiatric adverse effects, including aggression, depression, psychosis, and suicide.

Vitamin D is produced from cholesterol in the epidermis through exposure to sunlight, namely ultraviolet B radiation. After dermal synthesis or ingestion, vitamin D is converted through a series of steps into the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, which also is known as 25(OH)D3.

Although vitamin D is known for its role in bone growth and mineralization,31 increasing evidence reveals vitamin D’s role in brain function and development.32 Both glial and neuronal cells possess vitamin D receptors in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, and substantia nigra—all regions theorized to be linked to depression pathophysiology.33 A review of the association of vitamin D deficiency and psychiatric illnesses will be published in a future issue of Current Psychiatry.

Vitamin D exists in food as either D2 or D3, from plant and animal sources, respectively. Concentrated sources include oily fish, sun-dried or “UVB-irradiated” mushrooms, and milk.

Vitamin E. There are 8 isoforms of vitamin E—4 tocopherols and 4 tocotrienols—that function as fat-soluble antioxidants and also promote innate antioxidant enzymes. Because vitamin E protects neuronal membranes from oxidation, low levels may affect the brain via increased inflammation. Alpha-tocopherol is the most common form of vitamin E in humans, but emerging evidence suggests tocotrienols mediate disease by modifying transcription factors in the brain, such as glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and nuclear factor-kappaB.34 Low plasma vitamin E levels are found in depressed patients, although some data suggest this may be caused by factors other than dietary intake.35 Low vitamin status has been found in up to 70% of older adults.36 Although deficiency is rare, most of the U.S. population (93%) has inadequate dietary intake of vitamin E.1 The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. Foods rich in vitamin E include almonds, sunflower seeds, leafy greens, and wheat germ.

Recommendations

Patients with depression, alcohol abuse, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or schizophrenia may neglect to care for themselves or adopt particular eating patterns. Deficiencies are more common among geriatric patients and those who are medically ill. Because dietary patterns are linked to the risk of psychiatric disorders, nutritional inquiry often identifies multiple modifiable risk factors, such as folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D intake.37,38 Nutritional counseling offers clinicians an intervention with minimal side effect risks and the opportunity to modify a behavior that patients engage in 3 times a day.

Psychiatrists should assess patients’ dietary patterns and vitamin status, particularly older adults and those with:

- lower socioeconomic status or food insecurity

- a history of treatment resistance

- restrictive dietary patterns such as veganism

- alcohol abuse.

On initial assessment, test or obtain from other health care providers your patient’s blood levels of folate and vitamins D and B12. In some patients, assessing B2 and B6 levels may provide etiological guidance regarding onset of psychiatric symptoms or failure to respond to pharmacologic treatment. Because treating vitamin deficiencies often includes using supplements, evaluate recent reviews of specific deficiencies and consider consulting with the patient’s primary care provider.

Conduct a simple assessment of dietary patterns by asking patients about a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner, their favorite snacks and foods, and specific dietary habits or restrictions (eg, not consuming seafood, dairy, meat, etc.). Rudimentary nutritional recommendations can be effective in changing a patient’s eating habits, particularly when provided by a physician. Encourage patients to eat nutrient-dense foods such as leafy greens, beans and legumes, seafood, whole grains, and a variety of vegetables and fruits. For more complex patients, consult with a clinical nutritionist.

Related Resources

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Recommended intakes for individuals. SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf" target="_blank">www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/

SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf. - The Farmacy: Vitamins. http://drewramseymd.com/index.php/resources/farmacy/category/vitamins.

- Office of Dietary Supplements. National Institutes of Health. Dietary supplements fact sheets. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all.

- Oregon State University. Linus Pauling Institute. Micronutrient information center. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins.html.

Drug Brand Names

- Isotretinoin • Accutane

- L-methylfolate • Deplin

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. What we eat in America NHANES 2001-2002: Usual nutrient intakes from food compared to dietary reference intakes. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0102/usualintaketables2001-02.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed November 27, 2012.

2. Page GL, Laight D, Cummings MH. Thiamine deficiency in diabetes mellitus and the impact of thiamine replacement on glucose metabolism and vascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):684-690.

3. McCormick LM, Buchanan JR, Onwuameze OE, et al. Beyond alcoholism: Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in patients with psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(4):209-216.

4. Powers HJ. Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1352-1360.

5. Naghashpour M, Amani R, Nutr R, et al. Riboflavin status and its association with serum hs-CRP levels among clinical nurses with depression. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30(5):340-347.

6. Murakami K, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, et al. Dietary folate, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, and vitamin B-12 and depressive symptoms in early adolescence: the Ryukyus Child Health Study. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):763-768.

7. Merete C, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Vitamin B6 is associated with depressive symptomatology in Massachusetts elders. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(3):421-427.

8. Skarupski KA, Tangney C, Li H, et al. Longitudinal association of vitamin B-6, folate, and vitamin B-12 with depressive symptoms among older adults over time. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(2):330-335.

9. Corken M, Porter J. Is vitamin B(6) deficiency an under-recognized risk in patients receiving haemodialysis? A systematic review: 2000-2010. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16(7):619-625.

10. Wilson SM, Bivins BN, Russell KA, et al. Oral contraceptive use: impact on folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 status. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(10):572-583.

11. Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C. Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(1):59-65.

12. Tolmunen T, Voutilainen S, Hintikka J, et al. Dietary folate and depressive symptoms are associated in middle-aged Finnish men. J Nutr. 2003;133(10):3233-3236.

13. Gilbody S, Lightfoot T, Sheldon T. Is low folate a risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis and exploration of heterogeneity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(7):631-637.

14. Rösche J, Uhlmann C, Fröscher W. Low serum folate levels as a risk factor for depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(1):64-66.

15. Kale A, Naphade N, Sapkale S, et al. Reduced folic acid, vitamin B12 and docosahexaenoic acid and increased homocysteine and cortisol in never-medicated schizophrenia patients: implications for altered one-carbon metabolism. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):47-53.

16. Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

17. Di Palma C, Urani R, Agricola R, et al. Is methylfolate effective in relieving major depression in chronic alcoholics? A hypothesis of treatment. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1994;55(5):559-568.

18. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, et al. l-Methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for ssri-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

19. Baggott JE, Oster RA, Tamura T. Meta-analysis of cancer risk in folic acid supplementation trials. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(1):78-81.

20. Figueiredo JC, Grau MV, Haile RW, et al. Folic acid and risk of prostate cancer: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(6):432-435.

21. Kate N, Grover S, Agarwal M. Does B12 deficiency lead to lack of treatment response to conventional antidepressants? Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(11):42-44.

22. Hintikka J, Tolmunen T, Tanskanen A, et al. High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:17.-

23. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

24. Bar-Shai M, Gott D, Marmor S. Acute psychotic depression as a sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(4):384-386.

25. Sharma V, Biswas D. Cobalamin deficiency presenting as obsessive compulsive disorder: case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):578.e7-e8.

26. Vogiatzoglou A, Refsum H, Johnston C, et al. Vitamin B12 status and rate of brain volume loss in community-dwelling elderly. Neurology. 2008;71(11):826-832.

27. Smith A, Di Primio G, Humphrey-Murto S. Scurvy in the developed world. CMAJ. 2011;183(11):E752-E725.

28. Payne ME, Steck SE, George RR, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):2022-2027.

29. Dadheech G, Mishra S, Gautam S, et al. Oxidative stress, α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid and reduced glutathione status in schizophrenics. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2006;21(2):34-38.

30. Hinds TS, West WL, Knight EM. Carotenoids and retinoids: a review of research clinical, and public health applications. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(7):551-558.

31. Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50-60.

32. Berk M, Sanders KM, Pasco JA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency may play a role in depression. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1316-1319.

33. Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, et al. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29(1):21-30.

34. Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S. Tocotrienol: the natural vitamin E to defend the nervous system? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:127-142.

35. Owen AJ, Batterham MJ, Probst YC, et al. Low plasma vitamin E levels in major depression: diet or disease? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(2):304-306.

36. Panemangalore M, Lee CJ. Evaluation of the indices of retinol and alpha-tocopherol status in free-living elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47(3):B98-B104.

37. Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090-1098.

38. Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, et al. Association of Western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):305-311.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Patients today often are overfed but undernourished. A growing body of literature links dietary choices to brain health and the risk of psychiatric illness. Vitamin deficiencies can affect psychiatric patients in several ways:

- deficiencies may play a causative role in mental illness and exacerbate symptoms

- psychiatric symptoms can result in poor nutrition

- vitamin insufficiency—defined as subclinical deficiency—may compromise patient recovery.

Additionally, genetic differences may compromise vitamin and essential nutrient pathways.

Vitamins are dietary components other than carbohydrates, fats, minerals, and proteins that are necessary for life. B vitamins are required for proper functioning of the methylation cycle, monoamine production, DNA synthesis, and maintenance of phospholipids such as myelin (Figure). Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E play important roles in genetic transcription, antioxidant recycling, and inflammatory regulation in the brain.

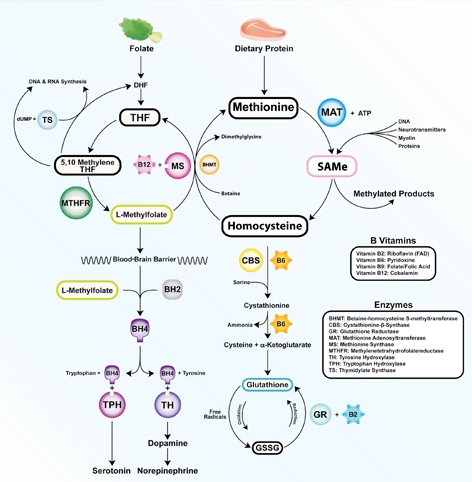

Figure: The methylation cycle

Vitamins B2, B6, B9, and B12 directly impact the functioning of the methylation cycle. Deficiencies pertain to brain function, as neurotransmitters, myelin, and active glutathione are dependent on one-carbon metabolism

Illustration: Mala Nimalasuriya with permission from DrewRamseyMD.com

To help clinicians recognize and treat vitamin deficiencies among psychiatric patients, this article reviews the role of the 6 essential water-soluble vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and C; Table 1,1) and 3 fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, and E; Table 2,1) in brain metabolism and psychiatric pathology. Because numerous sources address using supplements to treat vitamin deficiencies, this article emphasizes food sources, which for many patients are adequate to sustain nutrient status.

Table 1

Water-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (thiamine): Glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle | ||||

| Rare; 7% in heart failure patients | 5% total, 12% of older women | Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, memory impairment, confusion, lack of coordination, paralysis | Older adults, malabsorptive conditions, heavy alcohol use. Those with diabetes are at risk because of increased clearance | Pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ. Raw fish, tea, and betel nuts impair absorption |

| B2 (riboflavin): FMN, FAD cofactors in glycolysis and oxidative pathways. B6, folate, and glutathione synthesis | ||||

| 10% to 27% of older adults | <3%; 95% of adolescent girls (measured by EGRAC) | Fatigue, cracked lips, sore throat, bloodshot eyes | Older adults, low intake of animal and dairy products, heavy alcohol use | Dairy, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes |

| B6 (pyridoxal): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 11% to 24% (<5 ng/mL); 38% of heart failure patients | 14% total, 26% of adults | Dermatitis, glossitis, convulsions, migraine, chronic pain, depression | Older adults, women who use oral contraceptives, alcoholism. 33% to 49% of women age >51 have inadequate intake | Bananas, beans, potatoes, navy beans, salmon, steak, and whole grains |

| B9 (folate): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 0.5% total; up to 50% of depressed patients | 16% of adults, 19% of adolescent girls | Loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, heart palpitations, behavioral disorders | Depression, pregnancy and lactation, alcoholism, dialysis, liver disease. Deficiency during pregnancy is linked to neural tube defects | Leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans, and peas |

| B12 (cobalamin): Methylation cycle (cofactor methionine synthase) | ||||

| 10% to 15% of older adults | <3% to 9% | Depression, irritability, anemia, fatigue, shortness of breath, high blood pressure | Vegetarian or vegan diet, achlorhydria, older adults. Deficiency more often due to poor absorption than low consumption | Meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy |

| C (ascorbic acid): Antioxidant | ||||

| 7.1% | 31% | Scurvy, fatigue, anemia, joint pain, petechia. Symptoms develop after 1 to 3 months of no dietary intake | Smokers, infants fed boiled or evaporated milk, limited dietary variation, patients with malabsorption, chronic illnesses | Citrus fruits, tomatoes and tomato juice, and potatoes |

| EGRAC: erythrocyte glutathione reductase activation coefficient; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide; FMN: flavin mononucleotide Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Table 2

Fat-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (retinol): Transcription regulation, vision | ||||

| <5% of U.S. population | 44% | Blindness, decreased immunity, corneal and retinal damage | Pregnant women, individuals with strict dietary restrictions, heavy alcohol use, chronic diarrhea, fat malabsorptive conditions | Beef liver, dairy products. Convertible beta-carotene sources: sweet potatoes, carrots, spinach, butternut squash, greens, broccoli, cantaloupe |

| D (cholecalciferol): Hormone, transcriptional regulation | ||||

| ≥50%, 90% of adults age >50 | 69% | Rickets, osteoporosis, muscle twitching | Breast-fed infants, older adults, limited sun exposure, pigmented skin, fat malabsorption, obesity. Older adults have an impaired ability to make vitamin D from the sun. SPF 15 reduces production by 99% | Fatty fish and fish liver oils, sun-dried mushrooms |

| E (tocopherols and tocotrienols): Antioxidant, PUFA protectant, gene regulation | ||||

| Rare | 93% | Anemia, neuropathy, myopathy, abnormal eye movements, weakness, retinal damage | Malabsorptive conditions, HIV, depression | Sunflower, wheat germ, and safflower oils; meats; fish; dairy; green vegetables |

| HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; SPF: sun protection factor Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Water-soluble vitamins

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is essential for glucose metabolism. Pregnancy, lactation, and fever increase the need for thiamine, and tea, coffee, and shellfish can impair its absorption. Although rare, severe B1 deficiency can lead to beriberi, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ataxia, nystagmus), and Korsakoff’s psychosis (confabulation, lack of insight, retrograde and anterograde amnesia, and apathy). Confusion and disorientation stem from the brain’s inability to oxidize glucose for energy because B1 is a critical cofactor in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Deficiency leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory cytokines, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction.2 Wernicke’s encephalopathy is most frequently encountered in patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetes, or eating disorders, and after bariatric surgery.3 Iatrogenic Wernicke’s encephalopathy may occur when depleted patients receive IV saline with dextrose without receiving thiamine. Top dietary sources of B1 include pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ.

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is essential for oxidative pathways, monoamine synthesis, and the methylation cycle. B2 is needed to create the essential flavoprotein coenzymes for synthesis of L-methylfolate—the active form of folate—and for proper utilization of B6. Deficiency can occur after 4 months of inadequate intake.

Although generally B2 deficiency is rare, surveys in the United States have found that 10% to 27% of older adults (age ≥65) are deficient.4 Low intake of dairy products and meat and chronic, excessive alcohol intake are associated with deficiency. Marginal B2 levels are more prevalent in depressed patients, possibly because of B2’s role in the function of glutathione, an endogenous antioxidant.5 Top dietary sources of B2 are dairy products, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes.

Vitamin B6 refers to 3 distinct compounds: pyridoxine, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine. B6 is essential to glycolysis, the methylation cycle, and recharging glutathione, an innate antioxidant in the brain. Higher levels of vitamin B6 are associated with a lower prevalence of depression in adolescents,6 and low dietary and plasma B6 increases the risk and severity of depression in geriatric patients7 and predicts depression in prospective trials.8 Deficiency is common (24% to 56%) among patients receiving hemodialysis.9 Women who take oral contraceptives are at increased risk of vitamin B6 deficiency.10 Top dietary sources are fish, beef, poultry, potatoes, legumes, and spinach.

Vitamin B9 (folate) is needed for proper one-carbon metabolism and thus requisite in synthesis of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and DNA and in phospholipid production. Low maternal folate status increases the risk of neural tube defects in newborns. Folate deficiency and insufficiency are common among patients with mood disorders and correlate with illness severity.11 In a study of 2,682 Finnish men, those in the lowest one-third of folate consumption had a 67% increased relative risk of depression.12 A meta-analysis of 11 studies of 15,315 persons found those who had low folate levels had a significant risk of depression.13 Patients without deficiency but with folate levels near the low end of the normal range also report low mood.14 Compared with controls, patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis have lower levels of folate, B12, and docosahexaenoic acid.15

Dietary folate must be converted to L-methylfolate for use in the brain. Patients with a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism produce a less active form of the enzyme. The TT genotype is associated with major depression and bipolar disorder.16 Clinical trials have shown that several forms of folate can enhance antidepressant treatment.17 Augmentation with L-methylfolate, which bypasses the MTHFR enzyme, can be an effective strategy for treating depression in these patients.18

Leafy greens and legumes such as lentils are top dietary sources of folate; supplemental folic acid has been linked to an increased risk of cancer and overall mortality.19,20

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin). An essential cofactor in one-carbon metabolism, B12 is needed to produce monoamine neurotransmitters and maintain myelin. Deficiency is found in up to one-third of depressed patients11 and compromises antidepressant response,21 whereas higher vitamin B12 levels are associated with better treatment outcomes.22 B12 deficiency can cause depression, irritability, agitation, psychosis, and obsessive symptoms.23,24 Low B12 levels and elevated homocysteine increase the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and are linked to a 5-fold increase in the rate of brain atrophy.26

B12 deficiencies may be seen in patients with gastrointestinal illness, older adults with achlorhydria, and vegans and vegetarians, in whom B12 intake can be low. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole interfere with B12 absorption from food.

Psychiatric symptoms of B12 deficiency may present before hematologic findings.23 Folic acid supplementation may mask a B12 deficiency by delaying anemia but will not delay psychiatric symptoms. Ten percent of patients with an insufficiency (low normal levels of 200 to 400 pg/mL) have elevated homocysteine, which increases the risk of psychiatric disorders as well as comorbid illnesses such as cardiovascular disease. Top dietary sources include fish, mollusks (oysters, mussels, and clams), meat, and dairy products.

Vitamin C is vital for the synthesis of monoamines such as serotonin and norepinephrine. Vitamin C’s primary role in the brain is as an antioxidant. As a necessary cofactor, it keeps the copper and iron in metalloenzymes reduced, and also recycles vitamin E. Proper function of the methylation cycle depends on vitamin C, as does collagen synthesis and metabolism of xenobiotics by the liver. It is concentrated in cerebrospinal fluid.

Humans cannot manufacture vitamin C. Although the need for vitamin C (90 mg/d) is thought to be met by diet, studies have found that up to 13.7% of healthy, middle class patients in the United States are depleted.27 Older adults and patients with a poor diet due to drug or alcohol abuse, eating disorders, or affective symptoms are at risk.

Scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency and leads to bleeding gums and petechiae. Patients with insufficiency report irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, and hypochondriasis. Vitamin C intake is significantly lower in older adults (age ≥60) with depression.28 Some research indicates patients with schizophrenia have decreased vitamin C levels and dysfunction of antioxidant defenses.29 Citrus, potatoes, and tomatoes are top dietary sources of vitamin C.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A. Although vitamin A activity in the brain is poorly understood, retinol—the active form of vitamin A—is crucial for formation of opsins, which are the basis for vision. Childhood vitamin A deficiency may lead to blindness. Vitamin A also plays an important role in maintaining bone growth, reproduction, cell division, and immune system integrity.30 Animal sources such as beef liver, dairy products, and eggs provide retinol, and plant sources such as carrots, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens provide provitamin A carotenoids that humans convert into retinol.

Deficiency rarely is observed in the United States but remains a common problem for developing nations. In the United States, vitamin A deficiency is most often seen with excessive alcohol use, rigorous dietary restrictions, and gastrointestinal diseases accompanied by poor fat absorption.

Excess vitamin A ingestion may result in bone abnormalities, liver damage, birth defects, and depression. Isotretinoin—a form of vitamin A used to treat severe acne—carries an FDA “black-box” warning for psychiatric adverse effects, including aggression, depression, psychosis, and suicide.

Vitamin D is produced from cholesterol in the epidermis through exposure to sunlight, namely ultraviolet B radiation. After dermal synthesis or ingestion, vitamin D is converted through a series of steps into the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, which also is known as 25(OH)D3.

Although vitamin D is known for its role in bone growth and mineralization,31 increasing evidence reveals vitamin D’s role in brain function and development.32 Both glial and neuronal cells possess vitamin D receptors in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, and substantia nigra—all regions theorized to be linked to depression pathophysiology.33 A review of the association of vitamin D deficiency and psychiatric illnesses will be published in a future issue of Current Psychiatry.

Vitamin D exists in food as either D2 or D3, from plant and animal sources, respectively. Concentrated sources include oily fish, sun-dried or “UVB-irradiated” mushrooms, and milk.

Vitamin E. There are 8 isoforms of vitamin E—4 tocopherols and 4 tocotrienols—that function as fat-soluble antioxidants and also promote innate antioxidant enzymes. Because vitamin E protects neuronal membranes from oxidation, low levels may affect the brain via increased inflammation. Alpha-tocopherol is the most common form of vitamin E in humans, but emerging evidence suggests tocotrienols mediate disease by modifying transcription factors in the brain, such as glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and nuclear factor-kappaB.34 Low plasma vitamin E levels are found in depressed patients, although some data suggest this may be caused by factors other than dietary intake.35 Low vitamin status has been found in up to 70% of older adults.36 Although deficiency is rare, most of the U.S. population (93%) has inadequate dietary intake of vitamin E.1 The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. Foods rich in vitamin E include almonds, sunflower seeds, leafy greens, and wheat germ.

Recommendations

Patients with depression, alcohol abuse, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or schizophrenia may neglect to care for themselves or adopt particular eating patterns. Deficiencies are more common among geriatric patients and those who are medically ill. Because dietary patterns are linked to the risk of psychiatric disorders, nutritional inquiry often identifies multiple modifiable risk factors, such as folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D intake.37,38 Nutritional counseling offers clinicians an intervention with minimal side effect risks and the opportunity to modify a behavior that patients engage in 3 times a day.

Psychiatrists should assess patients’ dietary patterns and vitamin status, particularly older adults and those with:

- lower socioeconomic status or food insecurity

- a history of treatment resistance

- restrictive dietary patterns such as veganism

- alcohol abuse.

On initial assessment, test or obtain from other health care providers your patient’s blood levels of folate and vitamins D and B12. In some patients, assessing B2 and B6 levels may provide etiological guidance regarding onset of psychiatric symptoms or failure to respond to pharmacologic treatment. Because treating vitamin deficiencies often includes using supplements, evaluate recent reviews of specific deficiencies and consider consulting with the patient’s primary care provider.

Conduct a simple assessment of dietary patterns by asking patients about a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner, their favorite snacks and foods, and specific dietary habits or restrictions (eg, not consuming seafood, dairy, meat, etc.). Rudimentary nutritional recommendations can be effective in changing a patient’s eating habits, particularly when provided by a physician. Encourage patients to eat nutrient-dense foods such as leafy greens, beans and legumes, seafood, whole grains, and a variety of vegetables and fruits. For more complex patients, consult with a clinical nutritionist.

Related Resources

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Recommended intakes for individuals. SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf" target="_blank">www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/

SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf. - The Farmacy: Vitamins. http://drewramseymd.com/index.php/resources/farmacy/category/vitamins.

- Office of Dietary Supplements. National Institutes of Health. Dietary supplements fact sheets. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all.

- Oregon State University. Linus Pauling Institute. Micronutrient information center. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins.html.

Drug Brand Names

- Isotretinoin • Accutane

- L-methylfolate • Deplin

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Patients today often are overfed but undernourished. A growing body of literature links dietary choices to brain health and the risk of psychiatric illness. Vitamin deficiencies can affect psychiatric patients in several ways:

- deficiencies may play a causative role in mental illness and exacerbate symptoms

- psychiatric symptoms can result in poor nutrition

- vitamin insufficiency—defined as subclinical deficiency—may compromise patient recovery.

Additionally, genetic differences may compromise vitamin and essential nutrient pathways.

Vitamins are dietary components other than carbohydrates, fats, minerals, and proteins that are necessary for life. B vitamins are required for proper functioning of the methylation cycle, monoamine production, DNA synthesis, and maintenance of phospholipids such as myelin (Figure). Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E play important roles in genetic transcription, antioxidant recycling, and inflammatory regulation in the brain.

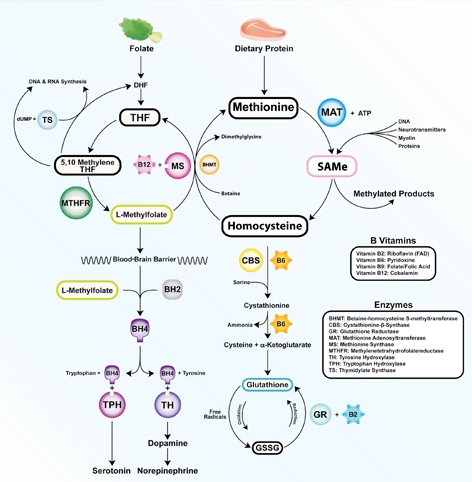

Figure: The methylation cycle

Vitamins B2, B6, B9, and B12 directly impact the functioning of the methylation cycle. Deficiencies pertain to brain function, as neurotransmitters, myelin, and active glutathione are dependent on one-carbon metabolism

Illustration: Mala Nimalasuriya with permission from DrewRamseyMD.com

To help clinicians recognize and treat vitamin deficiencies among psychiatric patients, this article reviews the role of the 6 essential water-soluble vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and C; Table 1,1) and 3 fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, and E; Table 2,1) in brain metabolism and psychiatric pathology. Because numerous sources address using supplements to treat vitamin deficiencies, this article emphasizes food sources, which for many patients are adequate to sustain nutrient status.

Table 1

Water-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (thiamine): Glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle | ||||

| Rare; 7% in heart failure patients | 5% total, 12% of older women | Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, memory impairment, confusion, lack of coordination, paralysis | Older adults, malabsorptive conditions, heavy alcohol use. Those with diabetes are at risk because of increased clearance | Pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ. Raw fish, tea, and betel nuts impair absorption |

| B2 (riboflavin): FMN, FAD cofactors in glycolysis and oxidative pathways. B6, folate, and glutathione synthesis | ||||

| 10% to 27% of older adults | <3%; 95% of adolescent girls (measured by EGRAC) | Fatigue, cracked lips, sore throat, bloodshot eyes | Older adults, low intake of animal and dairy products, heavy alcohol use | Dairy, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes |

| B6 (pyridoxal): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 11% to 24% (<5 ng/mL); 38% of heart failure patients | 14% total, 26% of adults | Dermatitis, glossitis, convulsions, migraine, chronic pain, depression | Older adults, women who use oral contraceptives, alcoholism. 33% to 49% of women age >51 have inadequate intake | Bananas, beans, potatoes, navy beans, salmon, steak, and whole grains |

| B9 (folate): Methylation cycle | ||||

| 0.5% total; up to 50% of depressed patients | 16% of adults, 19% of adolescent girls | Loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, heart palpitations, behavioral disorders | Depression, pregnancy and lactation, alcoholism, dialysis, liver disease. Deficiency during pregnancy is linked to neural tube defects | Leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans, and peas |

| B12 (cobalamin): Methylation cycle (cofactor methionine synthase) | ||||

| 10% to 15% of older adults | <3% to 9% | Depression, irritability, anemia, fatigue, shortness of breath, high blood pressure | Vegetarian or vegan diet, achlorhydria, older adults. Deficiency more often due to poor absorption than low consumption | Meat, seafood, eggs, and dairy |

| C (ascorbic acid): Antioxidant | ||||

| 7.1% | 31% | Scurvy, fatigue, anemia, joint pain, petechia. Symptoms develop after 1 to 3 months of no dietary intake | Smokers, infants fed boiled or evaporated milk, limited dietary variation, patients with malabsorption, chronic illnesses | Citrus fruits, tomatoes and tomato juice, and potatoes |

| EGRAC: erythrocyte glutathione reductase activation coefficient; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide; FMN: flavin mononucleotide Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Table 2

Fat-soluble vitamins: Deficiency, insufficiency, symptoms, and dietary sources

| Deficiency | Insufficiency | Symptoms | At-risk patients | Dietary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (retinol): Transcription regulation, vision | ||||

| <5% of U.S. population | 44% | Blindness, decreased immunity, corneal and retinal damage | Pregnant women, individuals with strict dietary restrictions, heavy alcohol use, chronic diarrhea, fat malabsorptive conditions | Beef liver, dairy products. Convertible beta-carotene sources: sweet potatoes, carrots, spinach, butternut squash, greens, broccoli, cantaloupe |

| D (cholecalciferol): Hormone, transcriptional regulation | ||||

| ≥50%, 90% of adults age >50 | 69% | Rickets, osteoporosis, muscle twitching | Breast-fed infants, older adults, limited sun exposure, pigmented skin, fat malabsorption, obesity. Older adults have an impaired ability to make vitamin D from the sun. SPF 15 reduces production by 99% | Fatty fish and fish liver oils, sun-dried mushrooms |

| E (tocopherols and tocotrienols): Antioxidant, PUFA protectant, gene regulation | ||||

| Rare | 93% | Anemia, neuropathy, myopathy, abnormal eye movements, weakness, retinal damage | Malabsorptive conditions, HIV, depression | Sunflower, wheat germ, and safflower oils; meats; fish; dairy; green vegetables |

| HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; SPF: sun protection factor Source: Reference 1 | ||||

Water-soluble vitamins

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is essential for glucose metabolism. Pregnancy, lactation, and fever increase the need for thiamine, and tea, coffee, and shellfish can impair its absorption. Although rare, severe B1 deficiency can lead to beriberi, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ataxia, nystagmus), and Korsakoff’s psychosis (confabulation, lack of insight, retrograde and anterograde amnesia, and apathy). Confusion and disorientation stem from the brain’s inability to oxidize glucose for energy because B1 is a critical cofactor in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Deficiency leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory cytokines, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction.2 Wernicke’s encephalopathy is most frequently encountered in patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetes, or eating disorders, and after bariatric surgery.3 Iatrogenic Wernicke’s encephalopathy may occur when depleted patients receive IV saline with dextrose without receiving thiamine. Top dietary sources of B1 include pork, fish, beans, lentils, nuts, rice, and wheat germ.

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is essential for oxidative pathways, monoamine synthesis, and the methylation cycle. B2 is needed to create the essential flavoprotein coenzymes for synthesis of L-methylfolate—the active form of folate—and for proper utilization of B6. Deficiency can occur after 4 months of inadequate intake.

Although generally B2 deficiency is rare, surveys in the United States have found that 10% to 27% of older adults (age ≥65) are deficient.4 Low intake of dairy products and meat and chronic, excessive alcohol intake are associated with deficiency. Marginal B2 levels are more prevalent in depressed patients, possibly because of B2’s role in the function of glutathione, an endogenous antioxidant.5 Top dietary sources of B2 are dairy products, meat and fish, eggs, mushrooms, almonds, leafy greens, and legumes.

Vitamin B6 refers to 3 distinct compounds: pyridoxine, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine. B6 is essential to glycolysis, the methylation cycle, and recharging glutathione, an innate antioxidant in the brain. Higher levels of vitamin B6 are associated with a lower prevalence of depression in adolescents,6 and low dietary and plasma B6 increases the risk and severity of depression in geriatric patients7 and predicts depression in prospective trials.8 Deficiency is common (24% to 56%) among patients receiving hemodialysis.9 Women who take oral contraceptives are at increased risk of vitamin B6 deficiency.10 Top dietary sources are fish, beef, poultry, potatoes, legumes, and spinach.

Vitamin B9 (folate) is needed for proper one-carbon metabolism and thus requisite in synthesis of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and DNA and in phospholipid production. Low maternal folate status increases the risk of neural tube defects in newborns. Folate deficiency and insufficiency are common among patients with mood disorders and correlate with illness severity.11 In a study of 2,682 Finnish men, those in the lowest one-third of folate consumption had a 67% increased relative risk of depression.12 A meta-analysis of 11 studies of 15,315 persons found those who had low folate levels had a significant risk of depression.13 Patients without deficiency but with folate levels near the low end of the normal range also report low mood.14 Compared with controls, patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis have lower levels of folate, B12, and docosahexaenoic acid.15

Dietary folate must be converted to L-methylfolate for use in the brain. Patients with a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism produce a less active form of the enzyme. The TT genotype is associated with major depression and bipolar disorder.16 Clinical trials have shown that several forms of folate can enhance antidepressant treatment.17 Augmentation with L-methylfolate, which bypasses the MTHFR enzyme, can be an effective strategy for treating depression in these patients.18

Leafy greens and legumes such as lentils are top dietary sources of folate; supplemental folic acid has been linked to an increased risk of cancer and overall mortality.19,20

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin). An essential cofactor in one-carbon metabolism, B12 is needed to produce monoamine neurotransmitters and maintain myelin. Deficiency is found in up to one-third of depressed patients11 and compromises antidepressant response,21 whereas higher vitamin B12 levels are associated with better treatment outcomes.22 B12 deficiency can cause depression, irritability, agitation, psychosis, and obsessive symptoms.23,24 Low B12 levels and elevated homocysteine increase the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and are linked to a 5-fold increase in the rate of brain atrophy.26

B12 deficiencies may be seen in patients with gastrointestinal illness, older adults with achlorhydria, and vegans and vegetarians, in whom B12 intake can be low. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole interfere with B12 absorption from food.

Psychiatric symptoms of B12 deficiency may present before hematologic findings.23 Folic acid supplementation may mask a B12 deficiency by delaying anemia but will not delay psychiatric symptoms. Ten percent of patients with an insufficiency (low normal levels of 200 to 400 pg/mL) have elevated homocysteine, which increases the risk of psychiatric disorders as well as comorbid illnesses such as cardiovascular disease. Top dietary sources include fish, mollusks (oysters, mussels, and clams), meat, and dairy products.

Vitamin C is vital for the synthesis of monoamines such as serotonin and norepinephrine. Vitamin C’s primary role in the brain is as an antioxidant. As a necessary cofactor, it keeps the copper and iron in metalloenzymes reduced, and also recycles vitamin E. Proper function of the methylation cycle depends on vitamin C, as does collagen synthesis and metabolism of xenobiotics by the liver. It is concentrated in cerebrospinal fluid.

Humans cannot manufacture vitamin C. Although the need for vitamin C (90 mg/d) is thought to be met by diet, studies have found that up to 13.7% of healthy, middle class patients in the United States are depleted.27 Older adults and patients with a poor diet due to drug or alcohol abuse, eating disorders, or affective symptoms are at risk.

Scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency and leads to bleeding gums and petechiae. Patients with insufficiency report irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, and hypochondriasis. Vitamin C intake is significantly lower in older adults (age ≥60) with depression.28 Some research indicates patients with schizophrenia have decreased vitamin C levels and dysfunction of antioxidant defenses.29 Citrus, potatoes, and tomatoes are top dietary sources of vitamin C.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A. Although vitamin A activity in the brain is poorly understood, retinol—the active form of vitamin A—is crucial for formation of opsins, which are the basis for vision. Childhood vitamin A deficiency may lead to blindness. Vitamin A also plays an important role in maintaining bone growth, reproduction, cell division, and immune system integrity.30 Animal sources such as beef liver, dairy products, and eggs provide retinol, and plant sources such as carrots, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens provide provitamin A carotenoids that humans convert into retinol.

Deficiency rarely is observed in the United States but remains a common problem for developing nations. In the United States, vitamin A deficiency is most often seen with excessive alcohol use, rigorous dietary restrictions, and gastrointestinal diseases accompanied by poor fat absorption.

Excess vitamin A ingestion may result in bone abnormalities, liver damage, birth defects, and depression. Isotretinoin—a form of vitamin A used to treat severe acne—carries an FDA “black-box” warning for psychiatric adverse effects, including aggression, depression, psychosis, and suicide.

Vitamin D is produced from cholesterol in the epidermis through exposure to sunlight, namely ultraviolet B radiation. After dermal synthesis or ingestion, vitamin D is converted through a series of steps into the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, which also is known as 25(OH)D3.

Although vitamin D is known for its role in bone growth and mineralization,31 increasing evidence reveals vitamin D’s role in brain function and development.32 Both glial and neuronal cells possess vitamin D receptors in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, and substantia nigra—all regions theorized to be linked to depression pathophysiology.33 A review of the association of vitamin D deficiency and psychiatric illnesses will be published in a future issue of Current Psychiatry.

Vitamin D exists in food as either D2 or D3, from plant and animal sources, respectively. Concentrated sources include oily fish, sun-dried or “UVB-irradiated” mushrooms, and milk.

Vitamin E. There are 8 isoforms of vitamin E—4 tocopherols and 4 tocotrienols—that function as fat-soluble antioxidants and also promote innate antioxidant enzymes. Because vitamin E protects neuronal membranes from oxidation, low levels may affect the brain via increased inflammation. Alpha-tocopherol is the most common form of vitamin E in humans, but emerging evidence suggests tocotrienols mediate disease by modifying transcription factors in the brain, such as glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and nuclear factor-kappaB.34 Low plasma vitamin E levels are found in depressed patients, although some data suggest this may be caused by factors other than dietary intake.35 Low vitamin status has been found in up to 70% of older adults.36 Although deficiency is rare, most of the U.S. population (93%) has inadequate dietary intake of vitamin E.1 The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. Foods rich in vitamin E include almonds, sunflower seeds, leafy greens, and wheat germ.

Recommendations

Patients with depression, alcohol abuse, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or schizophrenia may neglect to care for themselves or adopt particular eating patterns. Deficiencies are more common among geriatric patients and those who are medically ill. Because dietary patterns are linked to the risk of psychiatric disorders, nutritional inquiry often identifies multiple modifiable risk factors, such as folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D intake.37,38 Nutritional counseling offers clinicians an intervention with minimal side effect risks and the opportunity to modify a behavior that patients engage in 3 times a day.

Psychiatrists should assess patients’ dietary patterns and vitamin status, particularly older adults and those with:

- lower socioeconomic status or food insecurity

- a history of treatment resistance

- restrictive dietary patterns such as veganism

- alcohol abuse.

On initial assessment, test or obtain from other health care providers your patient’s blood levels of folate and vitamins D and B12. In some patients, assessing B2 and B6 levels may provide etiological guidance regarding onset of psychiatric symptoms or failure to respond to pharmacologic treatment. Because treating vitamin deficiencies often includes using supplements, evaluate recent reviews of specific deficiencies and consider consulting with the patient’s primary care provider.

Conduct a simple assessment of dietary patterns by asking patients about a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner, their favorite snacks and foods, and specific dietary habits or restrictions (eg, not consuming seafood, dairy, meat, etc.). Rudimentary nutritional recommendations can be effective in changing a patient’s eating habits, particularly when provided by a physician. Encourage patients to eat nutrient-dense foods such as leafy greens, beans and legumes, seafood, whole grains, and a variety of vegetables and fruits. For more complex patients, consult with a clinical nutritionist.

Related Resources

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Recommended intakes for individuals. SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf" target="_blank">www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/

SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files

/Activity%20Files/Nutrition

/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf. - The Farmacy: Vitamins. http://drewramseymd.com/index.php/resources/farmacy/category/vitamins.

- Office of Dietary Supplements. National Institutes of Health. Dietary supplements fact sheets. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all.

- Oregon State University. Linus Pauling Institute. Micronutrient information center. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins.html.

Drug Brand Names

- Isotretinoin • Accutane

- L-methylfolate • Deplin

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. What we eat in America NHANES 2001-2002: Usual nutrient intakes from food compared to dietary reference intakes. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0102/usualintaketables2001-02.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed November 27, 2012.

2. Page GL, Laight D, Cummings MH. Thiamine deficiency in diabetes mellitus and the impact of thiamine replacement on glucose metabolism and vascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):684-690.

3. McCormick LM, Buchanan JR, Onwuameze OE, et al. Beyond alcoholism: Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in patients with psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(4):209-216.

4. Powers HJ. Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1352-1360.

5. Naghashpour M, Amani R, Nutr R, et al. Riboflavin status and its association with serum hs-CRP levels among clinical nurses with depression. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30(5):340-347.

6. Murakami K, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, et al. Dietary folate, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, and vitamin B-12 and depressive symptoms in early adolescence: the Ryukyus Child Health Study. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):763-768.

7. Merete C, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Vitamin B6 is associated with depressive symptomatology in Massachusetts elders. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(3):421-427.

8. Skarupski KA, Tangney C, Li H, et al. Longitudinal association of vitamin B-6, folate, and vitamin B-12 with depressive symptoms among older adults over time. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(2):330-335.

9. Corken M, Porter J. Is vitamin B(6) deficiency an under-recognized risk in patients receiving haemodialysis? A systematic review: 2000-2010. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16(7):619-625.

10. Wilson SM, Bivins BN, Russell KA, et al. Oral contraceptive use: impact on folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 status. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(10):572-583.

11. Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C. Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(1):59-65.

12. Tolmunen T, Voutilainen S, Hintikka J, et al. Dietary folate and depressive symptoms are associated in middle-aged Finnish men. J Nutr. 2003;133(10):3233-3236.

13. Gilbody S, Lightfoot T, Sheldon T. Is low folate a risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis and exploration of heterogeneity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(7):631-637.

14. Rösche J, Uhlmann C, Fröscher W. Low serum folate levels as a risk factor for depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(1):64-66.

15. Kale A, Naphade N, Sapkale S, et al. Reduced folic acid, vitamin B12 and docosahexaenoic acid and increased homocysteine and cortisol in never-medicated schizophrenia patients: implications for altered one-carbon metabolism. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):47-53.

16. Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

17. Di Palma C, Urani R, Agricola R, et al. Is methylfolate effective in relieving major depression in chronic alcoholics? A hypothesis of treatment. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1994;55(5):559-568.

18. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, et al. l-Methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for ssri-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

19. Baggott JE, Oster RA, Tamura T. Meta-analysis of cancer risk in folic acid supplementation trials. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(1):78-81.

20. Figueiredo JC, Grau MV, Haile RW, et al. Folic acid and risk of prostate cancer: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(6):432-435.

21. Kate N, Grover S, Agarwal M. Does B12 deficiency lead to lack of treatment response to conventional antidepressants? Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(11):42-44.

22. Hintikka J, Tolmunen T, Tanskanen A, et al. High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:17.-

23. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

24. Bar-Shai M, Gott D, Marmor S. Acute psychotic depression as a sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(4):384-386.

25. Sharma V, Biswas D. Cobalamin deficiency presenting as obsessive compulsive disorder: case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):578.e7-e8.

26. Vogiatzoglou A, Refsum H, Johnston C, et al. Vitamin B12 status and rate of brain volume loss in community-dwelling elderly. Neurology. 2008;71(11):826-832.

27. Smith A, Di Primio G, Humphrey-Murto S. Scurvy in the developed world. CMAJ. 2011;183(11):E752-E725.

28. Payne ME, Steck SE, George RR, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):2022-2027.

29. Dadheech G, Mishra S, Gautam S, et al. Oxidative stress, α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid and reduced glutathione status in schizophrenics. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2006;21(2):34-38.

30. Hinds TS, West WL, Knight EM. Carotenoids and retinoids: a review of research clinical, and public health applications. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(7):551-558.

31. Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50-60.

32. Berk M, Sanders KM, Pasco JA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency may play a role in depression. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1316-1319.

33. Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, et al. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29(1):21-30.

34. Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S. Tocotrienol: the natural vitamin E to defend the nervous system? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:127-142.

35. Owen AJ, Batterham MJ, Probst YC, et al. Low plasma vitamin E levels in major depression: diet or disease? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(2):304-306.

36. Panemangalore M, Lee CJ. Evaluation of the indices of retinol and alpha-tocopherol status in free-living elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47(3):B98-B104.

37. Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090-1098.

38. Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, et al. Association of Western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):305-311.

1. Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. What we eat in America NHANES 2001-2002: Usual nutrient intakes from food compared to dietary reference intakes. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0102/usualintaketables2001-02.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed November 27, 2012.

2. Page GL, Laight D, Cummings MH. Thiamine deficiency in diabetes mellitus and the impact of thiamine replacement on glucose metabolism and vascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):684-690.

3. McCormick LM, Buchanan JR, Onwuameze OE, et al. Beyond alcoholism: Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in patients with psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(4):209-216.

4. Powers HJ. Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1352-1360.

5. Naghashpour M, Amani R, Nutr R, et al. Riboflavin status and its association with serum hs-CRP levels among clinical nurses with depression. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30(5):340-347.

6. Murakami K, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, et al. Dietary folate, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, and vitamin B-12 and depressive symptoms in early adolescence: the Ryukyus Child Health Study. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):763-768.

7. Merete C, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Vitamin B6 is associated with depressive symptomatology in Massachusetts elders. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(3):421-427.

8. Skarupski KA, Tangney C, Li H, et al. Longitudinal association of vitamin B-6, folate, and vitamin B-12 with depressive symptoms among older adults over time. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(2):330-335.

9. Corken M, Porter J. Is vitamin B(6) deficiency an under-recognized risk in patients receiving haemodialysis? A systematic review: 2000-2010. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16(7):619-625.

10. Wilson SM, Bivins BN, Russell KA, et al. Oral contraceptive use: impact on folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 status. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(10):572-583.

11. Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C. Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(1):59-65.

12. Tolmunen T, Voutilainen S, Hintikka J, et al. Dietary folate and depressive symptoms are associated in middle-aged Finnish men. J Nutr. 2003;133(10):3233-3236.

13. Gilbody S, Lightfoot T, Sheldon T. Is low folate a risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis and exploration of heterogeneity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(7):631-637.

14. Rösche J, Uhlmann C, Fröscher W. Low serum folate levels as a risk factor for depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(1):64-66.

15. Kale A, Naphade N, Sapkale S, et al. Reduced folic acid, vitamin B12 and docosahexaenoic acid and increased homocysteine and cortisol in never-medicated schizophrenia patients: implications for altered one-carbon metabolism. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):47-53.

16. Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

17. Di Palma C, Urani R, Agricola R, et al. Is methylfolate effective in relieving major depression in chronic alcoholics? A hypothesis of treatment. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1994;55(5):559-568.

18. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, et al. l-Methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for ssri-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

19. Baggott JE, Oster RA, Tamura T. Meta-analysis of cancer risk in folic acid supplementation trials. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(1):78-81.

20. Figueiredo JC, Grau MV, Haile RW, et al. Folic acid and risk of prostate cancer: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(6):432-435.

21. Kate N, Grover S, Agarwal M. Does B12 deficiency lead to lack of treatment response to conventional antidepressants? Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(11):42-44.

22. Hintikka J, Tolmunen T, Tanskanen A, et al. High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:17.-

23. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

24. Bar-Shai M, Gott D, Marmor S. Acute psychotic depression as a sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(4):384-386.

25. Sharma V, Biswas D. Cobalamin deficiency presenting as obsessive compulsive disorder: case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):578.e7-e8.

26. Vogiatzoglou A, Refsum H, Johnston C, et al. Vitamin B12 status and rate of brain volume loss in community-dwelling elderly. Neurology. 2008;71(11):826-832.

27. Smith A, Di Primio G, Humphrey-Murto S. Scurvy in the developed world. CMAJ. 2011;183(11):E752-E725.

28. Payne ME, Steck SE, George RR, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):2022-2027.

29. Dadheech G, Mishra S, Gautam S, et al. Oxidative stress, α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid and reduced glutathione status in schizophrenics. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2006;21(2):34-38.

30. Hinds TS, West WL, Knight EM. Carotenoids and retinoids: a review of research clinical, and public health applications. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(7):551-558.

31. Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50-60.

32. Berk M, Sanders KM, Pasco JA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency may play a role in depression. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1316-1319.

33. Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, et al. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29(1):21-30.

34. Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S. Tocotrienol: the natural vitamin E to defend the nervous system? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:127-142.

35. Owen AJ, Batterham MJ, Probst YC, et al. Low plasma vitamin E levels in major depression: diet or disease? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(2):304-306.

36. Panemangalore M, Lee CJ. Evaluation of the indices of retinol and alpha-tocopherol status in free-living elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47(3):B98-B104.

37. Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090-1098.

38. Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, et al. Association of Western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):305-311.