User login

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

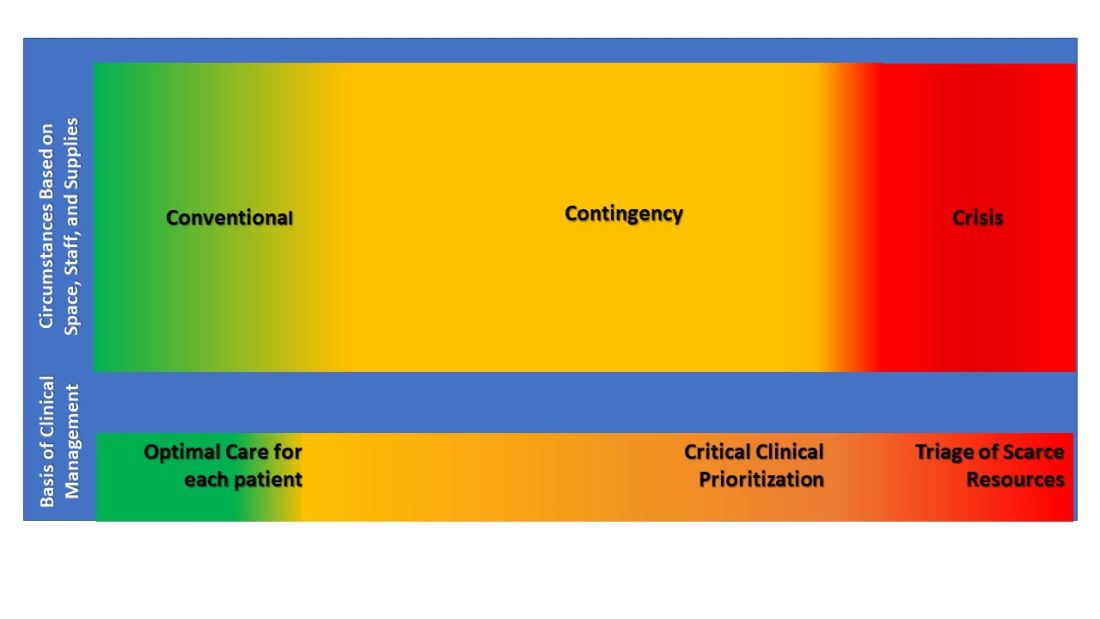

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

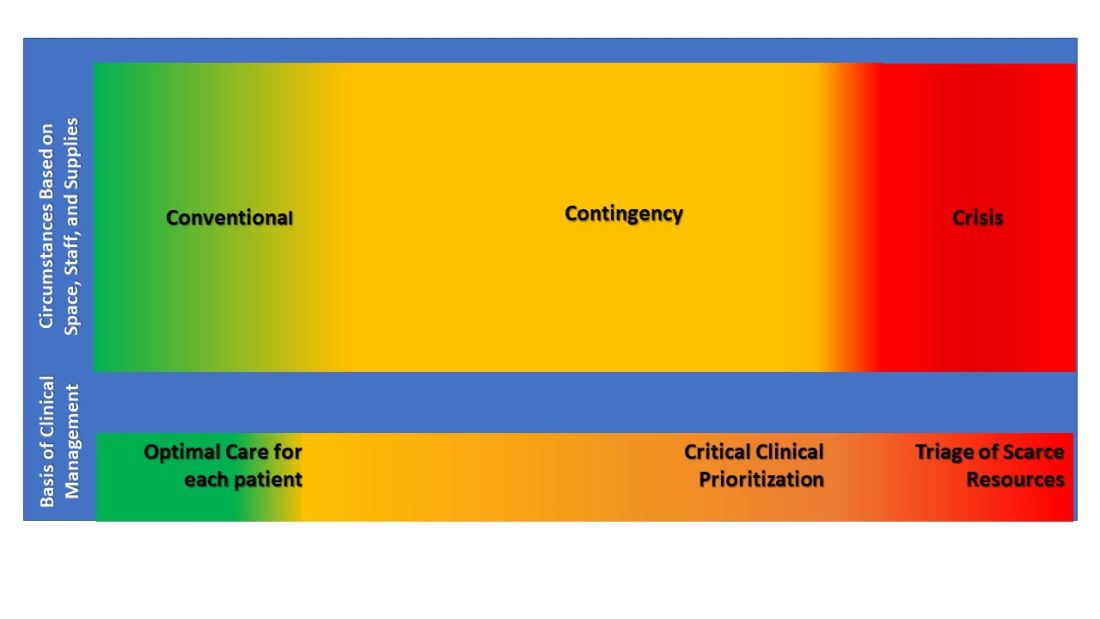

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

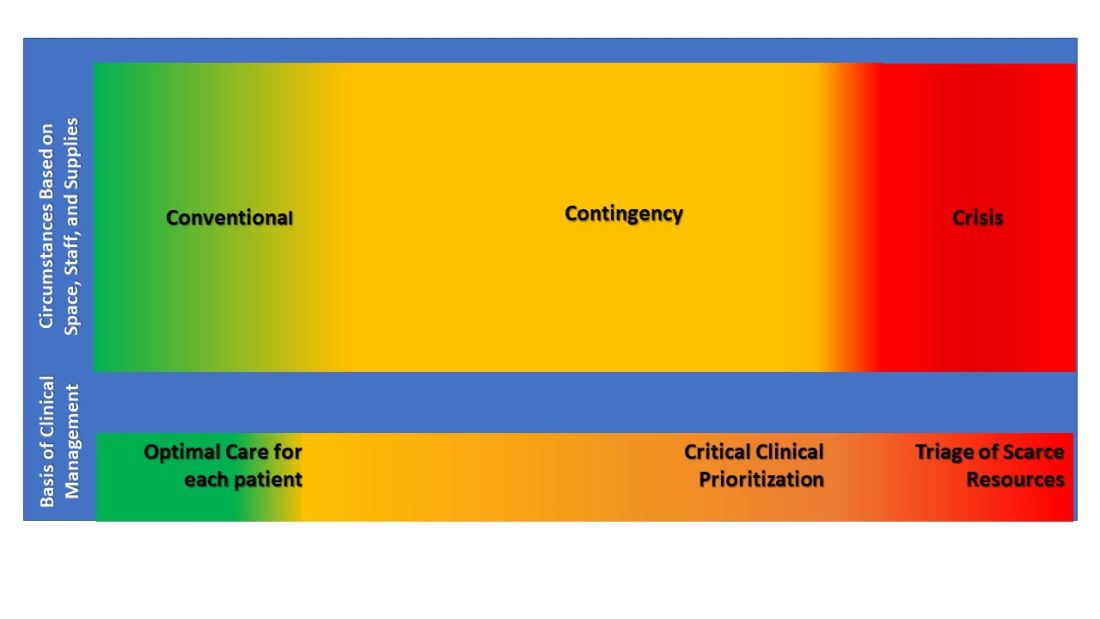

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.