User login

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

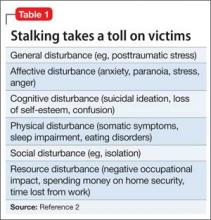

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

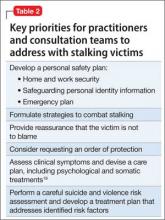

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.