User login

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

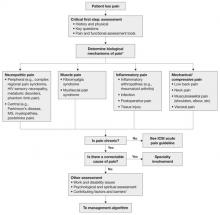

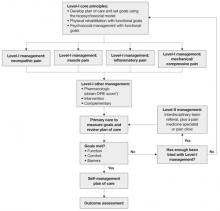

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.