User login

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

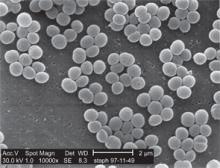

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

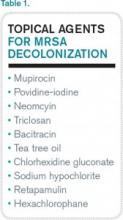

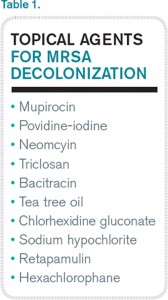

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.