User login

Several years into her hospitalist career, committee work had satisfied Sarita Satpathy, MD’s desire to positively impact patient care. Then she attended SHM’s Leadership Academy and was inspired to do more.

“I thought, ‘I want to do something and actually have a title where I can effect change,’” says Dr. Satpathy, now the hospitalist program medical director for Cogent HMG at Seton Medical Center in Daly City, Calif.

A year and a half after starting from scratch, Dr. Satpathy’s program has improved patient-care continuity, implemented 24/7 coverage, and earned buy-in from specialists, surgeons, and hospital leaders—most of whom are men.

“There aren’t as many female physician leaders, period,” says Dr. Satpathy, speaking of Seton Medical Center.

She could be talking about medicine in general.

Despite the fact that women have made up nearly half of all medical school graduates since 2005-2006 and make up 30% of the total physician population, only 16% of MD faculty at the full professor rank are female.1,2,3 Just 11% and 13% of medical school permanent deans and department chairs are women, respectively.4

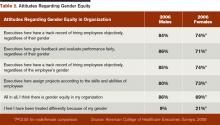

Beyond academia, results from surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives show that female healthcare executives are less likely to be CEOs and chief operating officers than their male counterparts. The results also indicate that the proportion of female CEOs remained fairly stable between surveys in 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2006; the proportion of female vice presidents actually decreased.5

This reality, experts say, undercuts America’s ability to remain at the leading edge of medical research, impedes women’s health improvements, and leaves fewer role models for future generations of physicians. In looking at why female physicians are underrepresented in leadership, key issues emerge, including unconscious bias, outdated work structures, lack of sponsorship, and conflict between the biological and professional time clocks. Although not all female doctors have faced these obstacles, many of them have and still do.

But opportunities are there—especially in HM—for female doctors to step into leadership roles. The onus is on women to seize them and on institutions to create a fertile environment for diverse leadership, physician leaders say.

Leadership Obstacles

Men often are associated with leadership by virtue of a phenomenon called unconscious bias, which posits that people identify certain genders with certain roles due to subconscious cues accumulated over time, says Hannah Valantine, MD, professor of medicine and senior associate dean for diversity and leadership at the Stanford

University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

“These biases exist in all of us in the way we evaluate women and their work, in the way we evaluate them for leadership positions and when they’re in leadership positions, and in the thought processes that they have of their own qualifications and actions,” says Molly Carnes, MD, MS, a professor of medicine and industrial and systems engineering and co-director of the Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Bias also exists in how institutions write their job announcements, performance evaluations, and grant and award applications, Dr. Carnes explains. When such terms as “aggressive” and “risk-taking” are used, women are less likely to be seen as viable candidates, she says.

What often impedes female physicians from taking leadership roles are a lack of sponsorship and obsolete work structures that don’t reflect life in the 21st century.

“There is some thought out there that women nowadays are overmentored and undersponsored,” says Dr. Valantine, a cardiologist. “By ‘sponsored,’ we mean going that extra mile to make sure a woman is promoted into the next level of leadership and into the next level of opportunities. It’s the ‘old boys’ network,’ and, unfortunately for women, there isn’t an old girls’ network that’s as well-oiled.”

Work environments are largely designed for the single breadwinner, even though most households, including physicians, have two earners. As a result, women who seek work flexibility or work part time often are labeled as “not serious about their careers,” Dr. Valantine says. This label affects women, who begin to think they can’t pursue leadership roles because they’re working less than full time, says Rachel George, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, chief operating officer of the West and North-Central regions and chief medical officer of the West region for Nashville, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG, the largest privately held HM and critical-care company in the nation with partnerships in more than 100 hospitals.

There’s an inherent conflict between the professional and biological time clocks in that when female hospitalists are trained, working for a few years, and ready to accept new challenges, they’re also starting families, says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West region for Dallas-based EmCare, a company that provides outsourced physician services, including hospitalist care, in more than 500 hospitals in 40 states.

“Part of the problem is that we look at this as an all or none, that you have to be fully immersed in whatever leadership role it is, and be willing to give a tremendous amount of hours, but that’s really not true,” Dr. George says. “There are different levels of leadership. It’s OK to take it slow and do a little bit, whatever the reasoning may be.”

Dr. Carnes says many women who achieve leadership positions find themselves outside the behavioral norms assigned to women and, therefore, often confront negative reactions and perceptions that they’re disagreeable, arrogant, and superior-minded. Women sometimes get pushback from other women, too.

“When you talk to stay-at-home moms and part-time moms, I think they try and put the guilt trip on you all the time,” says Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, board member of the American Women’s Medical Association and executive director of the National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

That, in turn, often compounds the internal guilt many women feel, pitting their work and leadership goals against their responsibilities at home, she says. “There is still a big pull for women to be at home, and when you’re not, you feel guilty about it,” Dr. Rohr-Kirchgraber explains.

Good Things Don’t Come to Those Who Wait

—Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC

Female hospitalists who aspire to lead must take the initiative, experts say.

“Regardless of gender, those individuals who are known to get results, be proactive, and be part of a solution are the ones who gain the attention and, many times, have opportunities open up for advancement,” says Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC, an executive leadership consultant and coach who teaches advanced courses at SHM’s Leadership Academy.

Cathleen Ammann, MD, can attest to that. A year after joining the then-fledgling hospitalist program at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., Dr. Ammann thought she could lead it in a positive direction.

“With zero leadership experience, I went to our CMO, who was basically the administrator for our group, and said, ‘I think I could do a good job with this,’” she says. The CMO concurred, and in October 2006, Dr. Ammann took over the hospitalist program, which she continues to lead today. “They really took a chance with me, and I’m glad they did.”

Dr. Bell says HM, as a whole, has more leadership opportunities than there are trained, capable physicians to do the job—something female hospitalists can take advantage of. But it’s up to women to seize the opportunity, says Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, who started her career as a hospitalist and is now CEO of Advanced ICU Care, a St. Louis-based firm that connects intensivists to hospital ICU patients via telemedicine.

“Every leadership position that I’ve been in, I got there because I was trying to solve a problem,” says Dr. Gorman, a past president of SHM. “The No. 1 mistake that women make is they don’t step up to volunteer to take responsibility for things; they expect somebody to notice their good work and ask them to lead. Culturally, that’s been shown not to be what happens and not very successful.”

—Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, CEO, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

Female hospitalists who are interested in leadership need to find an organization that values and encourages their employees to make meaningful contributions, Cannon says. Then they need to join projects and committees in order to develop some leadership qualities, Dr. Ammann says.

“Being involved in one or two committees initially that you strongly believe in, being active, voicing your opinion, and finding ways to find solutions─that’s where you get seen and known,” Dr. Satpathy says. “You actually gain credibility because it’s authentic.”

The old adage “from small beginnings come great things” applies to leadership, Dr. Gorman says.

“If you can complete things regularly and successfully, if you can do that, then the next time you go to a slightly bigger project and then a bigger project and a bigger project, until you’re directing a couple hundred people,” she says.

It’s also important for female physicians to find multiple mentors, Dr. Valantine notes. “You may need a mentor that is within your own discipline who can help guide you about planning your career, writing a grant, doing a project. You might need someone else entirely different who will help you think about when is the right time for you to consider having a family, taking sabbatical, and just integrating your work with life,” she says.

Additionally, female hospitalists pursuing leadership roles must remember that every time they say “yes” to something, they’re saying “no” to something else, Cannon says.

“Too often what I see is women are so eager to please and they’re so driven to be their best, they end up saying ‘yes’ in their career. Then, all of a sudden, they arrive at a point and they say, ‘Something is really missing,’” she says. “If you can get ahead of that and think through things, it’s really going to help your planning.”

Dr. Valantine says female physicians should “take the long view” of leadership and pace themselves.

“Look at this along the entire career path and say, ‘I may not be able to do everything right now, but there might be periods of flexing up and flexing down in my career, and that’s fine,’” she says. “The important thing is to stay in it.”

Dr. Bell and others urge hospitalists who are motivated to lead to tell people in positions of authority that they’re interested; otherwise, they’re not going to be thought of when a position opens.

Dr. Rohr-Kirchgarber has made appointments with deans, associate deans, and faculty affairs staff to introduce herself, explain her expertise, and find ways to use her skill sets in initiatives and committees that are important to the institution.

“Rather than waiting for three or four years for them to find out who I am and think about me for a committee, I need to get out there from Day One,” she says. “It’s proven to be successful.”

Drs. Ammann and Bell encourage hospitalists in community settings to approach their CMOs or other hospital administrators about their leadership aspirations. “And, of course, networking in a professional organization helps,” Dr. Satpathy says.

Meet Halfway

Female physicians can take the initiative and position themselves for leadership roles. They can acquire necessary skills by attending SHM’s Leadership Academy, management classes offered by the American College of Physicians and the American College of Physician Executives, and even adult education courses taught at business schools. But in order for them to be successful leaders, institutions must be invested in the effort.

Organizations can start by defining what they mean by “leadership.”

“‘Leader’ is actually a very abstract concept,” Dr. Carnes says. “But if you break it down into very specific activities, then I think you will get more women saying ‘yes.’ The first thing is getting women to see what leadership can allow them to do.”

—Rachel George, MBA, MCC

Men—and women—also have to acknowledge they have unconscious biases, then work to change the cultural norms, she says.

“Smoking is a really good example,” Dr. Carnes explains. “It took multilevel intervention at the individual and institutional level to change the cultural norms for smoking. You have to have a clear statement by the institution endorsed by all the institutional leaders that this is an institutional priority.” Examples of priorities include eliminating male-gendered words from job announcements and performance evaluations, and ensuring a fair and open application process for leadership positions that allow female physicians to make a case for themselves, she says.

Institutions can implement structural elements to help women—and men—better manage their careers and assume leadership roles, Dr. Valantine says. These include tenure clock extension, extended maternity and family leave, short- and long-term sabbaticals, onsite childcare, and emergency backup childcare.(Read about how Stanford University’s School of Medicine encourages women to seek leadership positions at the-hospitalist.org.)

“When I give talks to women about leadership, I tell them about all the programs we’re doing. I say to them, ‘I hope that you will go out and ask for these programs to be set up in your institutions,” she says. “But, more importantly, I tell women, ‘You have a responsibility to remain standing. It’s going to be tough sometimes, but if you don’t remain standing, we won’t have the role models that we need. It’s going to be a vicious cycle. We just won’t advance and increase the numbers of women leaders.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 1. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170248/data/2010_table1.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. American Medical Association, 2012. 2012 ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 4A. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170254/data/2009_table04a.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Figure 5. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/179458/data/2009_figure05.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American College of Healthcare Executives. A Comparison of the Career Attainments of Men and Women Healthcare Executives: 2006, Table 2. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/gender_study_full_report.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

Several years into her hospitalist career, committee work had satisfied Sarita Satpathy, MD’s desire to positively impact patient care. Then she attended SHM’s Leadership Academy and was inspired to do more.

“I thought, ‘I want to do something and actually have a title where I can effect change,’” says Dr. Satpathy, now the hospitalist program medical director for Cogent HMG at Seton Medical Center in Daly City, Calif.

A year and a half after starting from scratch, Dr. Satpathy’s program has improved patient-care continuity, implemented 24/7 coverage, and earned buy-in from specialists, surgeons, and hospital leaders—most of whom are men.

“There aren’t as many female physician leaders, period,” says Dr. Satpathy, speaking of Seton Medical Center.

She could be talking about medicine in general.

Despite the fact that women have made up nearly half of all medical school graduates since 2005-2006 and make up 30% of the total physician population, only 16% of MD faculty at the full professor rank are female.1,2,3 Just 11% and 13% of medical school permanent deans and department chairs are women, respectively.4

Beyond academia, results from surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives show that female healthcare executives are less likely to be CEOs and chief operating officers than their male counterparts. The results also indicate that the proportion of female CEOs remained fairly stable between surveys in 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2006; the proportion of female vice presidents actually decreased.5

This reality, experts say, undercuts America’s ability to remain at the leading edge of medical research, impedes women’s health improvements, and leaves fewer role models for future generations of physicians. In looking at why female physicians are underrepresented in leadership, key issues emerge, including unconscious bias, outdated work structures, lack of sponsorship, and conflict between the biological and professional time clocks. Although not all female doctors have faced these obstacles, many of them have and still do.

But opportunities are there—especially in HM—for female doctors to step into leadership roles. The onus is on women to seize them and on institutions to create a fertile environment for diverse leadership, physician leaders say.

Leadership Obstacles

Men often are associated with leadership by virtue of a phenomenon called unconscious bias, which posits that people identify certain genders with certain roles due to subconscious cues accumulated over time, says Hannah Valantine, MD, professor of medicine and senior associate dean for diversity and leadership at the Stanford

University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

“These biases exist in all of us in the way we evaluate women and their work, in the way we evaluate them for leadership positions and when they’re in leadership positions, and in the thought processes that they have of their own qualifications and actions,” says Molly Carnes, MD, MS, a professor of medicine and industrial and systems engineering and co-director of the Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Bias also exists in how institutions write their job announcements, performance evaluations, and grant and award applications, Dr. Carnes explains. When such terms as “aggressive” and “risk-taking” are used, women are less likely to be seen as viable candidates, she says.

What often impedes female physicians from taking leadership roles are a lack of sponsorship and obsolete work structures that don’t reflect life in the 21st century.

“There is some thought out there that women nowadays are overmentored and undersponsored,” says Dr. Valantine, a cardiologist. “By ‘sponsored,’ we mean going that extra mile to make sure a woman is promoted into the next level of leadership and into the next level of opportunities. It’s the ‘old boys’ network,’ and, unfortunately for women, there isn’t an old girls’ network that’s as well-oiled.”

Work environments are largely designed for the single breadwinner, even though most households, including physicians, have two earners. As a result, women who seek work flexibility or work part time often are labeled as “not serious about their careers,” Dr. Valantine says. This label affects women, who begin to think they can’t pursue leadership roles because they’re working less than full time, says Rachel George, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, chief operating officer of the West and North-Central regions and chief medical officer of the West region for Nashville, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG, the largest privately held HM and critical-care company in the nation with partnerships in more than 100 hospitals.

There’s an inherent conflict between the professional and biological time clocks in that when female hospitalists are trained, working for a few years, and ready to accept new challenges, they’re also starting families, says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West region for Dallas-based EmCare, a company that provides outsourced physician services, including hospitalist care, in more than 500 hospitals in 40 states.

“Part of the problem is that we look at this as an all or none, that you have to be fully immersed in whatever leadership role it is, and be willing to give a tremendous amount of hours, but that’s really not true,” Dr. George says. “There are different levels of leadership. It’s OK to take it slow and do a little bit, whatever the reasoning may be.”

Dr. Carnes says many women who achieve leadership positions find themselves outside the behavioral norms assigned to women and, therefore, often confront negative reactions and perceptions that they’re disagreeable, arrogant, and superior-minded. Women sometimes get pushback from other women, too.

“When you talk to stay-at-home moms and part-time moms, I think they try and put the guilt trip on you all the time,” says Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, board member of the American Women’s Medical Association and executive director of the National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

That, in turn, often compounds the internal guilt many women feel, pitting their work and leadership goals against their responsibilities at home, she says. “There is still a big pull for women to be at home, and when you’re not, you feel guilty about it,” Dr. Rohr-Kirchgraber explains.

Good Things Don’t Come to Those Who Wait

—Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC

Female hospitalists who aspire to lead must take the initiative, experts say.

“Regardless of gender, those individuals who are known to get results, be proactive, and be part of a solution are the ones who gain the attention and, many times, have opportunities open up for advancement,” says Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC, an executive leadership consultant and coach who teaches advanced courses at SHM’s Leadership Academy.

Cathleen Ammann, MD, can attest to that. A year after joining the then-fledgling hospitalist program at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., Dr. Ammann thought she could lead it in a positive direction.

“With zero leadership experience, I went to our CMO, who was basically the administrator for our group, and said, ‘I think I could do a good job with this,’” she says. The CMO concurred, and in October 2006, Dr. Ammann took over the hospitalist program, which she continues to lead today. “They really took a chance with me, and I’m glad they did.”

Dr. Bell says HM, as a whole, has more leadership opportunities than there are trained, capable physicians to do the job—something female hospitalists can take advantage of. But it’s up to women to seize the opportunity, says Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, who started her career as a hospitalist and is now CEO of Advanced ICU Care, a St. Louis-based firm that connects intensivists to hospital ICU patients via telemedicine.

“Every leadership position that I’ve been in, I got there because I was trying to solve a problem,” says Dr. Gorman, a past president of SHM. “The No. 1 mistake that women make is they don’t step up to volunteer to take responsibility for things; they expect somebody to notice their good work and ask them to lead. Culturally, that’s been shown not to be what happens and not very successful.”

—Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, CEO, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

Female hospitalists who are interested in leadership need to find an organization that values and encourages their employees to make meaningful contributions, Cannon says. Then they need to join projects and committees in order to develop some leadership qualities, Dr. Ammann says.

“Being involved in one or two committees initially that you strongly believe in, being active, voicing your opinion, and finding ways to find solutions─that’s where you get seen and known,” Dr. Satpathy says. “You actually gain credibility because it’s authentic.”

The old adage “from small beginnings come great things” applies to leadership, Dr. Gorman says.

“If you can complete things regularly and successfully, if you can do that, then the next time you go to a slightly bigger project and then a bigger project and a bigger project, until you’re directing a couple hundred people,” she says.

It’s also important for female physicians to find multiple mentors, Dr. Valantine notes. “You may need a mentor that is within your own discipline who can help guide you about planning your career, writing a grant, doing a project. You might need someone else entirely different who will help you think about when is the right time for you to consider having a family, taking sabbatical, and just integrating your work with life,” she says.

Additionally, female hospitalists pursuing leadership roles must remember that every time they say “yes” to something, they’re saying “no” to something else, Cannon says.

“Too often what I see is women are so eager to please and they’re so driven to be their best, they end up saying ‘yes’ in their career. Then, all of a sudden, they arrive at a point and they say, ‘Something is really missing,’” she says. “If you can get ahead of that and think through things, it’s really going to help your planning.”

Dr. Valantine says female physicians should “take the long view” of leadership and pace themselves.

“Look at this along the entire career path and say, ‘I may not be able to do everything right now, but there might be periods of flexing up and flexing down in my career, and that’s fine,’” she says. “The important thing is to stay in it.”

Dr. Bell and others urge hospitalists who are motivated to lead to tell people in positions of authority that they’re interested; otherwise, they’re not going to be thought of when a position opens.

Dr. Rohr-Kirchgarber has made appointments with deans, associate deans, and faculty affairs staff to introduce herself, explain her expertise, and find ways to use her skill sets in initiatives and committees that are important to the institution.

“Rather than waiting for three or four years for them to find out who I am and think about me for a committee, I need to get out there from Day One,” she says. “It’s proven to be successful.”

Drs. Ammann and Bell encourage hospitalists in community settings to approach their CMOs or other hospital administrators about their leadership aspirations. “And, of course, networking in a professional organization helps,” Dr. Satpathy says.

Meet Halfway

Female physicians can take the initiative and position themselves for leadership roles. They can acquire necessary skills by attending SHM’s Leadership Academy, management classes offered by the American College of Physicians and the American College of Physician Executives, and even adult education courses taught at business schools. But in order for them to be successful leaders, institutions must be invested in the effort.

Organizations can start by defining what they mean by “leadership.”

“‘Leader’ is actually a very abstract concept,” Dr. Carnes says. “But if you break it down into very specific activities, then I think you will get more women saying ‘yes.’ The first thing is getting women to see what leadership can allow them to do.”

—Rachel George, MBA, MCC

Men—and women—also have to acknowledge they have unconscious biases, then work to change the cultural norms, she says.

“Smoking is a really good example,” Dr. Carnes explains. “It took multilevel intervention at the individual and institutional level to change the cultural norms for smoking. You have to have a clear statement by the institution endorsed by all the institutional leaders that this is an institutional priority.” Examples of priorities include eliminating male-gendered words from job announcements and performance evaluations, and ensuring a fair and open application process for leadership positions that allow female physicians to make a case for themselves, she says.

Institutions can implement structural elements to help women—and men—better manage their careers and assume leadership roles, Dr. Valantine says. These include tenure clock extension, extended maternity and family leave, short- and long-term sabbaticals, onsite childcare, and emergency backup childcare.(Read about how Stanford University’s School of Medicine encourages women to seek leadership positions at the-hospitalist.org.)

“When I give talks to women about leadership, I tell them about all the programs we’re doing. I say to them, ‘I hope that you will go out and ask for these programs to be set up in your institutions,” she says. “But, more importantly, I tell women, ‘You have a responsibility to remain standing. It’s going to be tough sometimes, but if you don’t remain standing, we won’t have the role models that we need. It’s going to be a vicious cycle. We just won’t advance and increase the numbers of women leaders.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 1. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170248/data/2010_table1.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. American Medical Association, 2012. 2012 ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 4A. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170254/data/2009_table04a.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Figure 5. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/179458/data/2009_figure05.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American College of Healthcare Executives. A Comparison of the Career Attainments of Men and Women Healthcare Executives: 2006, Table 2. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/gender_study_full_report.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

Several years into her hospitalist career, committee work had satisfied Sarita Satpathy, MD’s desire to positively impact patient care. Then she attended SHM’s Leadership Academy and was inspired to do more.

“I thought, ‘I want to do something and actually have a title where I can effect change,’” says Dr. Satpathy, now the hospitalist program medical director for Cogent HMG at Seton Medical Center in Daly City, Calif.

A year and a half after starting from scratch, Dr. Satpathy’s program has improved patient-care continuity, implemented 24/7 coverage, and earned buy-in from specialists, surgeons, and hospital leaders—most of whom are men.

“There aren’t as many female physician leaders, period,” says Dr. Satpathy, speaking of Seton Medical Center.

She could be talking about medicine in general.

Despite the fact that women have made up nearly half of all medical school graduates since 2005-2006 and make up 30% of the total physician population, only 16% of MD faculty at the full professor rank are female.1,2,3 Just 11% and 13% of medical school permanent deans and department chairs are women, respectively.4

Beyond academia, results from surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives show that female healthcare executives are less likely to be CEOs and chief operating officers than their male counterparts. The results also indicate that the proportion of female CEOs remained fairly stable between surveys in 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2006; the proportion of female vice presidents actually decreased.5

This reality, experts say, undercuts America’s ability to remain at the leading edge of medical research, impedes women’s health improvements, and leaves fewer role models for future generations of physicians. In looking at why female physicians are underrepresented in leadership, key issues emerge, including unconscious bias, outdated work structures, lack of sponsorship, and conflict between the biological and professional time clocks. Although not all female doctors have faced these obstacles, many of them have and still do.

But opportunities are there—especially in HM—for female doctors to step into leadership roles. The onus is on women to seize them and on institutions to create a fertile environment for diverse leadership, physician leaders say.

Leadership Obstacles

Men often are associated with leadership by virtue of a phenomenon called unconscious bias, which posits that people identify certain genders with certain roles due to subconscious cues accumulated over time, says Hannah Valantine, MD, professor of medicine and senior associate dean for diversity and leadership at the Stanford

University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

“These biases exist in all of us in the way we evaluate women and their work, in the way we evaluate them for leadership positions and when they’re in leadership positions, and in the thought processes that they have of their own qualifications and actions,” says Molly Carnes, MD, MS, a professor of medicine and industrial and systems engineering and co-director of the Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Bias also exists in how institutions write their job announcements, performance evaluations, and grant and award applications, Dr. Carnes explains. When such terms as “aggressive” and “risk-taking” are used, women are less likely to be seen as viable candidates, she says.

What often impedes female physicians from taking leadership roles are a lack of sponsorship and obsolete work structures that don’t reflect life in the 21st century.

“There is some thought out there that women nowadays are overmentored and undersponsored,” says Dr. Valantine, a cardiologist. “By ‘sponsored,’ we mean going that extra mile to make sure a woman is promoted into the next level of leadership and into the next level of opportunities. It’s the ‘old boys’ network,’ and, unfortunately for women, there isn’t an old girls’ network that’s as well-oiled.”

Work environments are largely designed for the single breadwinner, even though most households, including physicians, have two earners. As a result, women who seek work flexibility or work part time often are labeled as “not serious about their careers,” Dr. Valantine says. This label affects women, who begin to think they can’t pursue leadership roles because they’re working less than full time, says Rachel George, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, chief operating officer of the West and North-Central regions and chief medical officer of the West region for Nashville, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG, the largest privately held HM and critical-care company in the nation with partnerships in more than 100 hospitals.

There’s an inherent conflict between the professional and biological time clocks in that when female hospitalists are trained, working for a few years, and ready to accept new challenges, they’re also starting families, says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West region for Dallas-based EmCare, a company that provides outsourced physician services, including hospitalist care, in more than 500 hospitals in 40 states.

“Part of the problem is that we look at this as an all or none, that you have to be fully immersed in whatever leadership role it is, and be willing to give a tremendous amount of hours, but that’s really not true,” Dr. George says. “There are different levels of leadership. It’s OK to take it slow and do a little bit, whatever the reasoning may be.”

Dr. Carnes says many women who achieve leadership positions find themselves outside the behavioral norms assigned to women and, therefore, often confront negative reactions and perceptions that they’re disagreeable, arrogant, and superior-minded. Women sometimes get pushback from other women, too.

“When you talk to stay-at-home moms and part-time moms, I think they try and put the guilt trip on you all the time,” says Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, board member of the American Women’s Medical Association and executive director of the National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

That, in turn, often compounds the internal guilt many women feel, pitting their work and leadership goals against their responsibilities at home, she says. “There is still a big pull for women to be at home, and when you’re not, you feel guilty about it,” Dr. Rohr-Kirchgraber explains.

Good Things Don’t Come to Those Who Wait

—Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC

Female hospitalists who aspire to lead must take the initiative, experts say.

“Regardless of gender, those individuals who are known to get results, be proactive, and be part of a solution are the ones who gain the attention and, many times, have opportunities open up for advancement,” says Kay Cannon, MBA, MCC, an executive leadership consultant and coach who teaches advanced courses at SHM’s Leadership Academy.

Cathleen Ammann, MD, can attest to that. A year after joining the then-fledgling hospitalist program at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., Dr. Ammann thought she could lead it in a positive direction.

“With zero leadership experience, I went to our CMO, who was basically the administrator for our group, and said, ‘I think I could do a good job with this,’” she says. The CMO concurred, and in October 2006, Dr. Ammann took over the hospitalist program, which she continues to lead today. “They really took a chance with me, and I’m glad they did.”

Dr. Bell says HM, as a whole, has more leadership opportunities than there are trained, capable physicians to do the job—something female hospitalists can take advantage of. But it’s up to women to seize the opportunity, says Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, who started her career as a hospitalist and is now CEO of Advanced ICU Care, a St. Louis-based firm that connects intensivists to hospital ICU patients via telemedicine.

“Every leadership position that I’ve been in, I got there because I was trying to solve a problem,” says Dr. Gorman, a past president of SHM. “The No. 1 mistake that women make is they don’t step up to volunteer to take responsibility for things; they expect somebody to notice their good work and ask them to lead. Culturally, that’s been shown not to be what happens and not very successful.”

—Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, CEO, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

Female hospitalists who are interested in leadership need to find an organization that values and encourages their employees to make meaningful contributions, Cannon says. Then they need to join projects and committees in order to develop some leadership qualities, Dr. Ammann says.

“Being involved in one or two committees initially that you strongly believe in, being active, voicing your opinion, and finding ways to find solutions─that’s where you get seen and known,” Dr. Satpathy says. “You actually gain credibility because it’s authentic.”

The old adage “from small beginnings come great things” applies to leadership, Dr. Gorman says.

“If you can complete things regularly and successfully, if you can do that, then the next time you go to a slightly bigger project and then a bigger project and a bigger project, until you’re directing a couple hundred people,” she says.

It’s also important for female physicians to find multiple mentors, Dr. Valantine notes. “You may need a mentor that is within your own discipline who can help guide you about planning your career, writing a grant, doing a project. You might need someone else entirely different who will help you think about when is the right time for you to consider having a family, taking sabbatical, and just integrating your work with life,” she says.

Additionally, female hospitalists pursuing leadership roles must remember that every time they say “yes” to something, they’re saying “no” to something else, Cannon says.

“Too often what I see is women are so eager to please and they’re so driven to be their best, they end up saying ‘yes’ in their career. Then, all of a sudden, they arrive at a point and they say, ‘Something is really missing,’” she says. “If you can get ahead of that and think through things, it’s really going to help your planning.”

Dr. Valantine says female physicians should “take the long view” of leadership and pace themselves.

“Look at this along the entire career path and say, ‘I may not be able to do everything right now, but there might be periods of flexing up and flexing down in my career, and that’s fine,’” she says. “The important thing is to stay in it.”

Dr. Bell and others urge hospitalists who are motivated to lead to tell people in positions of authority that they’re interested; otherwise, they’re not going to be thought of when a position opens.

Dr. Rohr-Kirchgarber has made appointments with deans, associate deans, and faculty affairs staff to introduce herself, explain her expertise, and find ways to use her skill sets in initiatives and committees that are important to the institution.

“Rather than waiting for three or four years for them to find out who I am and think about me for a committee, I need to get out there from Day One,” she says. “It’s proven to be successful.”

Drs. Ammann and Bell encourage hospitalists in community settings to approach their CMOs or other hospital administrators about their leadership aspirations. “And, of course, networking in a professional organization helps,” Dr. Satpathy says.

Meet Halfway

Female physicians can take the initiative and position themselves for leadership roles. They can acquire necessary skills by attending SHM’s Leadership Academy, management classes offered by the American College of Physicians and the American College of Physician Executives, and even adult education courses taught at business schools. But in order for them to be successful leaders, institutions must be invested in the effort.

Organizations can start by defining what they mean by “leadership.”

“‘Leader’ is actually a very abstract concept,” Dr. Carnes says. “But if you break it down into very specific activities, then I think you will get more women saying ‘yes.’ The first thing is getting women to see what leadership can allow them to do.”

—Rachel George, MBA, MCC

Men—and women—also have to acknowledge they have unconscious biases, then work to change the cultural norms, she says.

“Smoking is a really good example,” Dr. Carnes explains. “It took multilevel intervention at the individual and institutional level to change the cultural norms for smoking. You have to have a clear statement by the institution endorsed by all the institutional leaders that this is an institutional priority.” Examples of priorities include eliminating male-gendered words from job announcements and performance evaluations, and ensuring a fair and open application process for leadership positions that allow female physicians to make a case for themselves, she says.

Institutions can implement structural elements to help women—and men—better manage their careers and assume leadership roles, Dr. Valantine says. These include tenure clock extension, extended maternity and family leave, short- and long-term sabbaticals, onsite childcare, and emergency backup childcare.(Read about how Stanford University’s School of Medicine encourages women to seek leadership positions at the-hospitalist.org.)

“When I give talks to women about leadership, I tell them about all the programs we’re doing. I say to them, ‘I hope that you will go out and ask for these programs to be set up in your institutions,” she says. “But, more importantly, I tell women, ‘You have a responsibility to remain standing. It’s going to be tough sometimes, but if you don’t remain standing, we won’t have the role models that we need. It’s going to be a vicious cycle. We just won’t advance and increase the numbers of women leaders.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 1. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170248/data/2010_table1.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. American Medical Association, 2012. 2012 ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Table 4A. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/170254/data/2009_table04a.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010, Figure 5. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/179458/data/2009_figure05.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- American College of Healthcare Executives. A Comparison of the Career Attainments of Men and Women Healthcare Executives: 2006, Table 2. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/gender_study_full_report.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.