User login

The problem is enormous: Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common form of heart disease—responsible for 385,000 deaths in the United States in 2009 (http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts. htm). Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from CAD than the general population, and warrant consideration as a special population. You should be familiar with routine cardiac medications; your patients’ medical problems; potential cardiac-related interactions among their psychotropic medications; and interactions among illnesses in their mental health and medical health domains (Box).

CASE Type 2 diabetes mellitus plus a long history of heavy smoking

Ms. S, age 57, is an African American woman with chronic paranoid schizophrenia who has been seeing a psychiatrist for the past 10 years. Ms. S’s psychiatric symptoms have been well controlled on risperidone, 3 mg/d.

Ms. S has a family history of diabetes, hypertension, and early CAD (a brother died of a myocardial infarction [MI] in his late 40s). She continues to smoke 2 packs of unfiltered cigarettes daily, as she has done for the past 40 years.

The psychiatrist has been following American Diabetes Association/American Psychiatric Association guidelines for monitoring; he has noticed that Ms. S’s body mass index (BMI) has increased from 27 to 31 kg/m2 over the past year. She has developed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

At today’s visit, Ms. S arrives a few minutes late and appears flustered and out of breath. She explains that she had to climb a flight of stairs to get to office because the elevator is broken.

During the visit, the psychiatrist notes that Ms. S occasionally winces and massages her left shoulder.

Questions to ponder

• What else could the psychiatrist do to modify Ms. S’s cardiac risk factors?

• What is Ms. S’s 10-year risk of an acute coronary event?

• What should her physician do now?

Overview: Cardiac risk in patients with mental illness

Modifiable risks for CAD include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, T2DM, obesity (all of which, taken together, constitute the metabolic syndrome), smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle. Some risk factors, including sex, age, and family history, are not modifiable. Whether or not this modification leads to better outcomes, psychiatric comorbidity is associated with higher morbidity and mortality from CAD.

Whether a common underlying pathological process manifesting in both CAD and mental illness exists, or whether the association is causal, are not well understood. Symptoms characteristic of depression (apathy, amotivation) and schizophrenia (disorganization, paranoia) could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors.1,2

People with mental illness smoke at a higher rate than those who do not have mental illness.3 This finding is of particular relevance because smoking contributes to worse outcomes with respect to CAD, even when medications are prescribed to address metabolic risks.4

Lower socioeconomic status is associated with poorer prognosis from CAD5 and is a risk factor for depression.6 Depression is a strong independent predictor of worse survival in acute coronary syndromes.5 Some experts consider depression to be a stronger risk factor for MI than traditional medical risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and second-hand smoke.7

Interventions used to treat certain mental illnesses can exacerbate, or predispose to, metabolic syndrome (which, in turn, increases the risk of CAD). Although some studies have demonstrated metabolic derangements in medication-naïve patients who have a new diagnosis of schizophrenia,8 there is a clearly established association between second-generation antipsychotic use and obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM. This association prompted development in 2004 of consensus recommendations for cardiovascular monitoring of patients who are taking an atypical antipsychotic.9

Some studies suggest that the stress of mental illness contributes to the pathogen esis of CAD.8 Hypothesized mechanisms include:

• sympathetic activation

• vagal deactivation

• platelet activation

• hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical pathways

• anticholinergic mechanisms

• inflammatory mediators, including cytokines.

Mental stress itself has the capacity to induce coronary ischemia.10 The mental stress of psychiatric illness could have an important pathophysiologic role in CAD. It can be tempting to disregard chest pain in a patient who is known to have panic disorder, but that patient might in fact be experiencing stress-induced myocardial ischemia.11

As many as 30% to 40% of patients with CAD suffer from clinically significant symptoms of depression; as many as 20% of patients with CAD meet criteria for major depressive disorder, compared with 5% to 10% of people who do not have CAD.2 Depression post-MI has been associated with a higher rate of sudden cardiac death and worse outcomes.12

Anxiety also can portend worse outcomes from CAD,13 including higher all-cause mortality.14 There is some hope, but limited evidence, that treating depression and anxiety, whether with antidepressant medication or behavioral therapy, can improve CAD outcomes.10,15

Making a diagnosis of CAD

CAD can present in a variety of ways, ranging from unrecognized or so-called silent CAD (there is an association between T2DM and unrecognized CAD and between hypertension and unrecognized CAD) to stable angina, unstable angina, acute coronary syndrome, MI, and sudden cardiac death. A variety of abnormalities on resting and exercise electrocardiogram (ECG), including ST segment depression, ST elevation, Q waves, and other morphological changes are indicative of CAD.

Other modalities, including coronary calcification score on computed tomography and coronary angiography can confirm the presence of CAD. Some clinicians recommend periodic ECG treadmill testing in patients who have:

• a total cholesterol level is >240 mg/dL

• systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, or both

• a family history of MI or sudden cardiac death in young (age <60) first-degree relatives

• a history of smoking

• diabetes.

Preventive guidelines

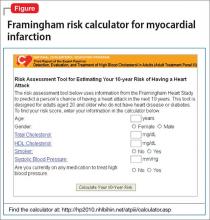

Risk stratification. A low (<10%), moderate (10% to 20%), or high (>20%) 10-year risk of CAD can be ascertained using a risk calculator, such as one that is available through the Framingham Heart Study (Figure) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (http://cvdrisk.nhlbi. nih.gov). Because patients with risk factors for CAD should be offered interventions— including smoking cessation therapy, diet and exercise, aspirin, lipid-lowering therapy, and blood pressure modification strategies—whether or not they have evidence of CAD, the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend for or against diagnostic screening in patients at moderate or elevated risk of CAD.16

There are guidelines in the literature recommending specific screening strategies for patients with mental illness, although the vetting and update process has been ill defined. Among patients with schizophrenia, though, regardless of antipsychotic prescription status, baseline and then regular monitoring of metabolic risk parameters is recommended.17

Primary prevention. Lifestyle modification and attention to modifiable coronary risk factors are important primary prevention strategies. Dietary modifications, exercise, not smoking, and maintenance of a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) are associated with a lower risk of CAD.18,19

Lifestyle modifications can be challenging for patients with persistent mental illness, however: For example, patients with schizophrenia smoke more, eat less healthfully, and participate less in behavioral modification that targets risk factors than patients who do not have schizophrenia.20,21

According to 2012 evidence-based practice guidelines established by a collaboration that included the American College of Physicians and several cardiology and thoracic medicine societies, persons age >50 who do not have symptomatic CAD should take low-dose (75 to 100 mg/d) aspirin; the benefit of low-dose aspirin in persons at moderate or high risk of CAD is even greater. Other medications, including statins and fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive medications in combination with a statin are not clearly beneficial as primary prevention strategies across the board, although selected high-risk populations might benefit.

Regrettably, the high-risk population of persons with mental illness and whose primary care is suboptimal has not been studied. It stands to reason that these patients would especially benefit from more attentive monitoring and intervention.

Collaborative care? Although many psychiatrists do not practice in such a model, a comprehensive approach to the care of their patients, using a collaborative care strategy that includes attention to the mental health diagnosis along with medical health, can result in improved health in both domains.22 However, enlisting patients with paranoia or an inherent distrust of medications and health care providers to adhere to either a medication regimen or lifestyle modification can be challenging.

Common-sense strategies, such as creating a multidisciplinary team with the psychiatrist coordinating care and optimizing antipsychotic treatment, might provide benefit.1 Data demonstrate that patients with severe mental illness who experience acute coronary events undergo revascularization at a lower rate than their mentally heathy counterparts, despite the fact that patients with severe mental illness die at a higher rate from their CAD than patients who do not have mental illness. An important role for the psychiatrist, even in the absence of a collaborative care program, is to be an advocate for appropriate guideline-based care.23

Secondary prevention. Once a patient develops CAD, ongoing risk factor modification is important. Adherence to a therapeutic regimen that variously combines a platelet inhibitor, beta blocker, statin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is associated with improved outcomes in patients with CAD.24 Specific antiplatelet recommendations and a recommendation for single vs combination antiplatelet therapy depends on chronicity and type of revascularization in a setting of CAD.25

Summary of guideline-based recommendations

Treatment guidelines published in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse address depression, CAD screening, and specific cardiac therapies, including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, oral anticoagulants, platelet inhibitors, beta blockers, and lifestyle modification.

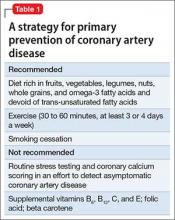

Primary prevention. Recommendations for treatment to prevent CAD are listed in Table 1.

Secondary prevention. Recommendations for treatment after a diagnosis of CAD are listed in Table 2.

Special considerations for psychiatric providers

You should be comfortable with patients’ use of antihypertensive therapies and familiar with the potential these agents have to interact with psychotropics; in addition, you can take a more active role in prescribing, and monitoring patients’ responses to, these medications. Provide appropriate monitoring of ACE inhibitors, statins, and beta blockers; also, provide appropriate monitoring of psychotropics in patients who take recommended cardioprotective medications.

In situations that prompt referral (such as recent MI, new symptoms of heart failure, any history of syncope or new identification of T2DM), ideally you should collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider to help enhance adherence to recommended treatment strategies. You also should employ motivational interviewing techniques and offer strategies by which patients can engage in meaningful lifestyle modification.

There are official recommendations for depression screening strategies26 and psychosocial risk screening for patients in whom CAD has been identified.27 Official screening strategies for CAD in patients with psychiatric illness have not, however, been spelled out.

Primary CAD prevention with medication is not routinely recommended for the general population, but the increased risk of CAD associated with psychiatric diagnoses (particularly schizophrenia, as well as the medications used to treat it) might warrant consideration of aggressive primary prevention strategies.28 For example, some experts recommend starting metformin to reduce the risk of T2DM in patients who have been started on olanzapine or clozapine, regardless of the baseline fasting blood glucose level.29

You should be fully informed and aware of patients’ underlying medical conditions and the medications that are recommended to treat their conditions. Ideally, an integrated care strategy or, at the least, clear communication between you and the patient’s primary care providers should be in place to avoid foreseeable problems.

Stimulants. Systematic reviews suggest an association between prescription stimulants and at least the 2 cardiovascular risk factors of elevated heart rate and blood pressure. Stimulants are not recommended, therefore, for routine use in patients who have known hypertension or CAD.30

Second-generation antipsychotics are associated with significant weight gain and development of metabolic syndrome.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding risk related to platelet inhibition and gastric effects. Risk increases with additional platelet inhibitors, such as aspirin or clopidogrel.31

Lithium is excreted solely by the kidney. Guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor-blockers for patients with CAD or T2DM, and many patients with symptomatic congestive heart failure are prescribed a diuretic; all of these classes of medications impair excretion of lithium. In a nested case-control study, 3% of observed cases of lithium toxicity were attributable to a newly initiated ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor-blocker.32 It is essential that you, and your patients taking lithium, be aware of the need to monitor the drug level frequently and be vigilant for symptoms of mild toxicity.

Beta blockers. No prospectively collected data support a association between beta blockers and depression.33 Patients with CAD should be given a trial of a beta blocker to achieve optimal medical management; because they are at increased risk of depression in the first place, all patients with CAD should undergo monitoring for depressive symptoms.

Clopidogrel is activated through the cytochrome P450 2C19 isoenzyme; medications such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine that inhibit the function of CYP2C19 can impair the effectiveness of clopidogrel.31

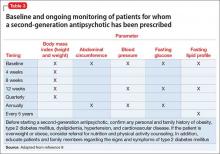

Other considerations. Patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic should have baseline and periodic (monthly for the first quarter, then quarterly) assessments of BMI and, after monitoring at 3 months after baseline, annual monitoring of blood pressure, the fasting glucose level, and abdominal waist circumference. Lipid levels should be monitored every 5 years9 (Table 3).

Baseline and periodic monitoring of hepatic enzymes is recommended for patients taking a statin. You, and the patient, should be alert to the possible development of muscle weakness or pain; establish a low threshold for screening for an elevated creatine kinase level, which signals rhabdomyolysis.

Case concluded

Ms. S’s psychiatrist measures her blood pressure and finds that it is 147/92 mm Hg. He uses the Pooled Cohort Equations to determine that her lifetime risk of cardiovascular event is 50% (compared with a 8% lifetime risk among a cohort in whom risk factors are optimized) and that her 10-year risk is 41% (compared with a 2.2% risk among optimized controls).

At this point, the psychiatrist starts metformin to prevent T2DM. He also starts Ms. S on a statin to prevent CAD in a setting of diagnosed T2DM.

Ms. S’s exertional dyspnea and shoulder discomfort could be associated with angina, and the physician wisely refers her for urgent evaluation. Because he is aware of the literature demonstrating decreased revascularization among patients with mental illness, he urges her other health care providers to provide her with guideline-based strategies to treat her cardiovascular disease.

Bottom Line

Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population. Symptoms characteristic of depression and schizophrenia could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors. Institute strategies for primary and secondary prevention of CAD among your patients, based on published guidelines, and be aware of, and alert for, adverse cardiac effects and an increase in risk factors for CAD from the use of psychotropics.

Related Resources

• Elderon L, Whooley MA. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(6):511-523.

• Interactive cardiovascular risk calculator developed from the Framingham Heart Study. https://www.framingham heartstudy.org/risk-functions/cardiovascular-disease/ 10-year-risk.php.

• Pooled Cohort Equations calculator. To determine estimated cardiovascular risk in comparison with peers with optimized risk factors. http://clincalc.com/cardiology/ascvd/ pooledcohort.aspx.

• To learn more about traditional cardiovascular risk factors from the Framingham Heart Study. http://www.framinghamheart study.org/risk-functions/.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Felodipine • Plendil

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heald A, Montejo AL, Millar H, et al. Management of physical health in patients with schizophrenia: practical recommendations. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S41-S45.

2. Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, et al. Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;2013:695925. doi: 10.1155/2013/695925.

3. Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick ZR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285.

4. Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Katsiki N, et al; GREACE Study Collaborative Group. The impact of smoking on cardiovascular outcomes and comorbidities in statin-treated patients with coronary artery disease: a post hoc analysis of the GREACE study. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11(5):779-784.

5. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 AACF/ AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44-e164.

6. Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):359-367.

7. Pozuelo L, Tesar G, Zhang J, et al. Depression and heart disease: what do we know, and where are we headed? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(1):59-70.

8. Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, et al. Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illnesses: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:84.

9. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

10. Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: results of the REMIT trial. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2139-2049.

11. Soares-Filho GL, Mesquita CT, Mesquita ET, et al. Panic attack triggering myocardial ischemia documented by myocardial perfusion imaging study. A case report. Int Arch Med. 2012;5(1):24.

12. Khawaja IS, Westermeyer JJ, Gajwani P, et al. Depression and coronary artery disease: the association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(1):38-51.

13. Wang G, Cui J, Wang Y, et al. Anxiety and adverse coronary artery disease outcomes in Chinese patients. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):530-536.

14. Watkins LL, Koch GG, Sherwood A, et al. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000068. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000068.

15. Chiavarino C, Rabellino D, Ardito RB, et al. Emotional coping is a better predictor of cardiac prognosis than depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(6):473-475.

16. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):512-518.

17. De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;199(2):99-105.

18. Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J, et al. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2.

19. Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rexrode KM, et al. Adherence to a low-risk, healthy lifestyle and risk of sudden cardiac death among women. JAMA. 2011;306(1):62-69.

20. Davidson M. Risk of cardiovascular disease and sudden death in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 9):5-11.

21. Dipasquale S, Pariante CM, Dazzan P, et al. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):197-207.

22. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611-2620.

23. Manderbacka K, Arffman M, Sund R, et al. How does a history of psychiatric hospital care influence access to coronary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000831. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000831.

24. Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al; REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health Registry Investigators. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):693-700.

25. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence- Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e637S-e668S.

26. Lichtman JH, Bigger T, Blumenthal JA, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; American Psychiatric Association. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768-1775.

27. Albus C, Jordan J, Herrmann-Lingen C. Screening for psychosocial risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease-recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(1):75-79.

28. Srihari VH, Phutane VH, Ozkan B, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia: defining a critical period for prevention. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1-3):64-68.

29. Brooks JO 3rd, Chang HS, Krasnykh O. Metabolic risks in older adults receiving second-generation antipsychotic medication. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):33-40.

30. Martinez-Raga J, Knecht C, Szerman N, et al. Risk of serious cardiovascular problems with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(1):15-30.

31. Andrade C. Drug interactions in the treatment of depression in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):e1475-e1477.

32. Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Kopp A, et al. Drug-induced lithium toxicity in the elderly: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):794-798.

33. Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP. Do beta blockers cause depression? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):50,51,55.

The problem is enormous: Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common form of heart disease—responsible for 385,000 deaths in the United States in 2009 (http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts. htm). Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from CAD than the general population, and warrant consideration as a special population. You should be familiar with routine cardiac medications; your patients’ medical problems; potential cardiac-related interactions among their psychotropic medications; and interactions among illnesses in their mental health and medical health domains (Box).

CASE Type 2 diabetes mellitus plus a long history of heavy smoking

Ms. S, age 57, is an African American woman with chronic paranoid schizophrenia who has been seeing a psychiatrist for the past 10 years. Ms. S’s psychiatric symptoms have been well controlled on risperidone, 3 mg/d.

Ms. S has a family history of diabetes, hypertension, and early CAD (a brother died of a myocardial infarction [MI] in his late 40s). She continues to smoke 2 packs of unfiltered cigarettes daily, as she has done for the past 40 years.

The psychiatrist has been following American Diabetes Association/American Psychiatric Association guidelines for monitoring; he has noticed that Ms. S’s body mass index (BMI) has increased from 27 to 31 kg/m2 over the past year. She has developed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

At today’s visit, Ms. S arrives a few minutes late and appears flustered and out of breath. She explains that she had to climb a flight of stairs to get to office because the elevator is broken.

During the visit, the psychiatrist notes that Ms. S occasionally winces and massages her left shoulder.

Questions to ponder

• What else could the psychiatrist do to modify Ms. S’s cardiac risk factors?

• What is Ms. S’s 10-year risk of an acute coronary event?

• What should her physician do now?

Overview: Cardiac risk in patients with mental illness

Modifiable risks for CAD include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, T2DM, obesity (all of which, taken together, constitute the metabolic syndrome), smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle. Some risk factors, including sex, age, and family history, are not modifiable. Whether or not this modification leads to better outcomes, psychiatric comorbidity is associated with higher morbidity and mortality from CAD.

Whether a common underlying pathological process manifesting in both CAD and mental illness exists, or whether the association is causal, are not well understood. Symptoms characteristic of depression (apathy, amotivation) and schizophrenia (disorganization, paranoia) could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors.1,2

People with mental illness smoke at a higher rate than those who do not have mental illness.3 This finding is of particular relevance because smoking contributes to worse outcomes with respect to CAD, even when medications are prescribed to address metabolic risks.4

Lower socioeconomic status is associated with poorer prognosis from CAD5 and is a risk factor for depression.6 Depression is a strong independent predictor of worse survival in acute coronary syndromes.5 Some experts consider depression to be a stronger risk factor for MI than traditional medical risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and second-hand smoke.7

Interventions used to treat certain mental illnesses can exacerbate, or predispose to, metabolic syndrome (which, in turn, increases the risk of CAD). Although some studies have demonstrated metabolic derangements in medication-naïve patients who have a new diagnosis of schizophrenia,8 there is a clearly established association between second-generation antipsychotic use and obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM. This association prompted development in 2004 of consensus recommendations for cardiovascular monitoring of patients who are taking an atypical antipsychotic.9

Some studies suggest that the stress of mental illness contributes to the pathogen esis of CAD.8 Hypothesized mechanisms include:

• sympathetic activation

• vagal deactivation

• platelet activation

• hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical pathways

• anticholinergic mechanisms

• inflammatory mediators, including cytokines.

Mental stress itself has the capacity to induce coronary ischemia.10 The mental stress of psychiatric illness could have an important pathophysiologic role in CAD. It can be tempting to disregard chest pain in a patient who is known to have panic disorder, but that patient might in fact be experiencing stress-induced myocardial ischemia.11

As many as 30% to 40% of patients with CAD suffer from clinically significant symptoms of depression; as many as 20% of patients with CAD meet criteria for major depressive disorder, compared with 5% to 10% of people who do not have CAD.2 Depression post-MI has been associated with a higher rate of sudden cardiac death and worse outcomes.12

Anxiety also can portend worse outcomes from CAD,13 including higher all-cause mortality.14 There is some hope, but limited evidence, that treating depression and anxiety, whether with antidepressant medication or behavioral therapy, can improve CAD outcomes.10,15

Making a diagnosis of CAD

CAD can present in a variety of ways, ranging from unrecognized or so-called silent CAD (there is an association between T2DM and unrecognized CAD and between hypertension and unrecognized CAD) to stable angina, unstable angina, acute coronary syndrome, MI, and sudden cardiac death. A variety of abnormalities on resting and exercise electrocardiogram (ECG), including ST segment depression, ST elevation, Q waves, and other morphological changes are indicative of CAD.

Other modalities, including coronary calcification score on computed tomography and coronary angiography can confirm the presence of CAD. Some clinicians recommend periodic ECG treadmill testing in patients who have:

• a total cholesterol level is >240 mg/dL

• systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, or both

• a family history of MI or sudden cardiac death in young (age <60) first-degree relatives

• a history of smoking

• diabetes.

Preventive guidelines

Risk stratification. A low (<10%), moderate (10% to 20%), or high (>20%) 10-year risk of CAD can be ascertained using a risk calculator, such as one that is available through the Framingham Heart Study (Figure) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (http://cvdrisk.nhlbi. nih.gov). Because patients with risk factors for CAD should be offered interventions— including smoking cessation therapy, diet and exercise, aspirin, lipid-lowering therapy, and blood pressure modification strategies—whether or not they have evidence of CAD, the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend for or against diagnostic screening in patients at moderate or elevated risk of CAD.16

There are guidelines in the literature recommending specific screening strategies for patients with mental illness, although the vetting and update process has been ill defined. Among patients with schizophrenia, though, regardless of antipsychotic prescription status, baseline and then regular monitoring of metabolic risk parameters is recommended.17

Primary prevention. Lifestyle modification and attention to modifiable coronary risk factors are important primary prevention strategies. Dietary modifications, exercise, not smoking, and maintenance of a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) are associated with a lower risk of CAD.18,19

Lifestyle modifications can be challenging for patients with persistent mental illness, however: For example, patients with schizophrenia smoke more, eat less healthfully, and participate less in behavioral modification that targets risk factors than patients who do not have schizophrenia.20,21

According to 2012 evidence-based practice guidelines established by a collaboration that included the American College of Physicians and several cardiology and thoracic medicine societies, persons age >50 who do not have symptomatic CAD should take low-dose (75 to 100 mg/d) aspirin; the benefit of low-dose aspirin in persons at moderate or high risk of CAD is even greater. Other medications, including statins and fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive medications in combination with a statin are not clearly beneficial as primary prevention strategies across the board, although selected high-risk populations might benefit.

Regrettably, the high-risk population of persons with mental illness and whose primary care is suboptimal has not been studied. It stands to reason that these patients would especially benefit from more attentive monitoring and intervention.

Collaborative care? Although many psychiatrists do not practice in such a model, a comprehensive approach to the care of their patients, using a collaborative care strategy that includes attention to the mental health diagnosis along with medical health, can result in improved health in both domains.22 However, enlisting patients with paranoia or an inherent distrust of medications and health care providers to adhere to either a medication regimen or lifestyle modification can be challenging.

Common-sense strategies, such as creating a multidisciplinary team with the psychiatrist coordinating care and optimizing antipsychotic treatment, might provide benefit.1 Data demonstrate that patients with severe mental illness who experience acute coronary events undergo revascularization at a lower rate than their mentally heathy counterparts, despite the fact that patients with severe mental illness die at a higher rate from their CAD than patients who do not have mental illness. An important role for the psychiatrist, even in the absence of a collaborative care program, is to be an advocate for appropriate guideline-based care.23

Secondary prevention. Once a patient develops CAD, ongoing risk factor modification is important. Adherence to a therapeutic regimen that variously combines a platelet inhibitor, beta blocker, statin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is associated with improved outcomes in patients with CAD.24 Specific antiplatelet recommendations and a recommendation for single vs combination antiplatelet therapy depends on chronicity and type of revascularization in a setting of CAD.25

Summary of guideline-based recommendations

Treatment guidelines published in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse address depression, CAD screening, and specific cardiac therapies, including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, oral anticoagulants, platelet inhibitors, beta blockers, and lifestyle modification.

Primary prevention. Recommendations for treatment to prevent CAD are listed in Table 1.

Secondary prevention. Recommendations for treatment after a diagnosis of CAD are listed in Table 2.

Special considerations for psychiatric providers

You should be comfortable with patients’ use of antihypertensive therapies and familiar with the potential these agents have to interact with psychotropics; in addition, you can take a more active role in prescribing, and monitoring patients’ responses to, these medications. Provide appropriate monitoring of ACE inhibitors, statins, and beta blockers; also, provide appropriate monitoring of psychotropics in patients who take recommended cardioprotective medications.

In situations that prompt referral (such as recent MI, new symptoms of heart failure, any history of syncope or new identification of T2DM), ideally you should collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider to help enhance adherence to recommended treatment strategies. You also should employ motivational interviewing techniques and offer strategies by which patients can engage in meaningful lifestyle modification.

There are official recommendations for depression screening strategies26 and psychosocial risk screening for patients in whom CAD has been identified.27 Official screening strategies for CAD in patients with psychiatric illness have not, however, been spelled out.

Primary CAD prevention with medication is not routinely recommended for the general population, but the increased risk of CAD associated with psychiatric diagnoses (particularly schizophrenia, as well as the medications used to treat it) might warrant consideration of aggressive primary prevention strategies.28 For example, some experts recommend starting metformin to reduce the risk of T2DM in patients who have been started on olanzapine or clozapine, regardless of the baseline fasting blood glucose level.29

You should be fully informed and aware of patients’ underlying medical conditions and the medications that are recommended to treat their conditions. Ideally, an integrated care strategy or, at the least, clear communication between you and the patient’s primary care providers should be in place to avoid foreseeable problems.

Stimulants. Systematic reviews suggest an association between prescription stimulants and at least the 2 cardiovascular risk factors of elevated heart rate and blood pressure. Stimulants are not recommended, therefore, for routine use in patients who have known hypertension or CAD.30

Second-generation antipsychotics are associated with significant weight gain and development of metabolic syndrome.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding risk related to platelet inhibition and gastric effects. Risk increases with additional platelet inhibitors, such as aspirin or clopidogrel.31

Lithium is excreted solely by the kidney. Guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor-blockers for patients with CAD or T2DM, and many patients with symptomatic congestive heart failure are prescribed a diuretic; all of these classes of medications impair excretion of lithium. In a nested case-control study, 3% of observed cases of lithium toxicity were attributable to a newly initiated ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor-blocker.32 It is essential that you, and your patients taking lithium, be aware of the need to monitor the drug level frequently and be vigilant for symptoms of mild toxicity.

Beta blockers. No prospectively collected data support a association between beta blockers and depression.33 Patients with CAD should be given a trial of a beta blocker to achieve optimal medical management; because they are at increased risk of depression in the first place, all patients with CAD should undergo monitoring for depressive symptoms.

Clopidogrel is activated through the cytochrome P450 2C19 isoenzyme; medications such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine that inhibit the function of CYP2C19 can impair the effectiveness of clopidogrel.31

Other considerations. Patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic should have baseline and periodic (monthly for the first quarter, then quarterly) assessments of BMI and, after monitoring at 3 months after baseline, annual monitoring of blood pressure, the fasting glucose level, and abdominal waist circumference. Lipid levels should be monitored every 5 years9 (Table 3).

Baseline and periodic monitoring of hepatic enzymes is recommended for patients taking a statin. You, and the patient, should be alert to the possible development of muscle weakness or pain; establish a low threshold for screening for an elevated creatine kinase level, which signals rhabdomyolysis.

Case concluded

Ms. S’s psychiatrist measures her blood pressure and finds that it is 147/92 mm Hg. He uses the Pooled Cohort Equations to determine that her lifetime risk of cardiovascular event is 50% (compared with a 8% lifetime risk among a cohort in whom risk factors are optimized) and that her 10-year risk is 41% (compared with a 2.2% risk among optimized controls).

At this point, the psychiatrist starts metformin to prevent T2DM. He also starts Ms. S on a statin to prevent CAD in a setting of diagnosed T2DM.

Ms. S’s exertional dyspnea and shoulder discomfort could be associated with angina, and the physician wisely refers her for urgent evaluation. Because he is aware of the literature demonstrating decreased revascularization among patients with mental illness, he urges her other health care providers to provide her with guideline-based strategies to treat her cardiovascular disease.

Bottom Line

Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population. Symptoms characteristic of depression and schizophrenia could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors. Institute strategies for primary and secondary prevention of CAD among your patients, based on published guidelines, and be aware of, and alert for, adverse cardiac effects and an increase in risk factors for CAD from the use of psychotropics.

Related Resources

• Elderon L, Whooley MA. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(6):511-523.

• Interactive cardiovascular risk calculator developed from the Framingham Heart Study. https://www.framingham heartstudy.org/risk-functions/cardiovascular-disease/ 10-year-risk.php.

• Pooled Cohort Equations calculator. To determine estimated cardiovascular risk in comparison with peers with optimized risk factors. http://clincalc.com/cardiology/ascvd/ pooledcohort.aspx.

• To learn more about traditional cardiovascular risk factors from the Framingham Heart Study. http://www.framinghamheart study.org/risk-functions/.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Felodipine • Plendil

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The problem is enormous: Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common form of heart disease—responsible for 385,000 deaths in the United States in 2009 (http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts. htm). Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from CAD than the general population, and warrant consideration as a special population. You should be familiar with routine cardiac medications; your patients’ medical problems; potential cardiac-related interactions among their psychotropic medications; and interactions among illnesses in their mental health and medical health domains (Box).

CASE Type 2 diabetes mellitus plus a long history of heavy smoking

Ms. S, age 57, is an African American woman with chronic paranoid schizophrenia who has been seeing a psychiatrist for the past 10 years. Ms. S’s psychiatric symptoms have been well controlled on risperidone, 3 mg/d.

Ms. S has a family history of diabetes, hypertension, and early CAD (a brother died of a myocardial infarction [MI] in his late 40s). She continues to smoke 2 packs of unfiltered cigarettes daily, as she has done for the past 40 years.

The psychiatrist has been following American Diabetes Association/American Psychiatric Association guidelines for monitoring; he has noticed that Ms. S’s body mass index (BMI) has increased from 27 to 31 kg/m2 over the past year. She has developed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

At today’s visit, Ms. S arrives a few minutes late and appears flustered and out of breath. She explains that she had to climb a flight of stairs to get to office because the elevator is broken.

During the visit, the psychiatrist notes that Ms. S occasionally winces and massages her left shoulder.

Questions to ponder

• What else could the psychiatrist do to modify Ms. S’s cardiac risk factors?

• What is Ms. S’s 10-year risk of an acute coronary event?

• What should her physician do now?

Overview: Cardiac risk in patients with mental illness

Modifiable risks for CAD include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, T2DM, obesity (all of which, taken together, constitute the metabolic syndrome), smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle. Some risk factors, including sex, age, and family history, are not modifiable. Whether or not this modification leads to better outcomes, psychiatric comorbidity is associated with higher morbidity and mortality from CAD.

Whether a common underlying pathological process manifesting in both CAD and mental illness exists, or whether the association is causal, are not well understood. Symptoms characteristic of depression (apathy, amotivation) and schizophrenia (disorganization, paranoia) could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors.1,2

People with mental illness smoke at a higher rate than those who do not have mental illness.3 This finding is of particular relevance because smoking contributes to worse outcomes with respect to CAD, even when medications are prescribed to address metabolic risks.4

Lower socioeconomic status is associated with poorer prognosis from CAD5 and is a risk factor for depression.6 Depression is a strong independent predictor of worse survival in acute coronary syndromes.5 Some experts consider depression to be a stronger risk factor for MI than traditional medical risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and second-hand smoke.7

Interventions used to treat certain mental illnesses can exacerbate, or predispose to, metabolic syndrome (which, in turn, increases the risk of CAD). Although some studies have demonstrated metabolic derangements in medication-naïve patients who have a new diagnosis of schizophrenia,8 there is a clearly established association between second-generation antipsychotic use and obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM. This association prompted development in 2004 of consensus recommendations for cardiovascular monitoring of patients who are taking an atypical antipsychotic.9

Some studies suggest that the stress of mental illness contributes to the pathogen esis of CAD.8 Hypothesized mechanisms include:

• sympathetic activation

• vagal deactivation

• platelet activation

• hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical pathways

• anticholinergic mechanisms

• inflammatory mediators, including cytokines.

Mental stress itself has the capacity to induce coronary ischemia.10 The mental stress of psychiatric illness could have an important pathophysiologic role in CAD. It can be tempting to disregard chest pain in a patient who is known to have panic disorder, but that patient might in fact be experiencing stress-induced myocardial ischemia.11

As many as 30% to 40% of patients with CAD suffer from clinically significant symptoms of depression; as many as 20% of patients with CAD meet criteria for major depressive disorder, compared with 5% to 10% of people who do not have CAD.2 Depression post-MI has been associated with a higher rate of sudden cardiac death and worse outcomes.12

Anxiety also can portend worse outcomes from CAD,13 including higher all-cause mortality.14 There is some hope, but limited evidence, that treating depression and anxiety, whether with antidepressant medication or behavioral therapy, can improve CAD outcomes.10,15

Making a diagnosis of CAD

CAD can present in a variety of ways, ranging from unrecognized or so-called silent CAD (there is an association between T2DM and unrecognized CAD and between hypertension and unrecognized CAD) to stable angina, unstable angina, acute coronary syndrome, MI, and sudden cardiac death. A variety of abnormalities on resting and exercise electrocardiogram (ECG), including ST segment depression, ST elevation, Q waves, and other morphological changes are indicative of CAD.

Other modalities, including coronary calcification score on computed tomography and coronary angiography can confirm the presence of CAD. Some clinicians recommend periodic ECG treadmill testing in patients who have:

• a total cholesterol level is >240 mg/dL

• systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, or both

• a family history of MI or sudden cardiac death in young (age <60) first-degree relatives

• a history of smoking

• diabetes.

Preventive guidelines

Risk stratification. A low (<10%), moderate (10% to 20%), or high (>20%) 10-year risk of CAD can be ascertained using a risk calculator, such as one that is available through the Framingham Heart Study (Figure) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (http://cvdrisk.nhlbi. nih.gov). Because patients with risk factors for CAD should be offered interventions— including smoking cessation therapy, diet and exercise, aspirin, lipid-lowering therapy, and blood pressure modification strategies—whether or not they have evidence of CAD, the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend for or against diagnostic screening in patients at moderate or elevated risk of CAD.16

There are guidelines in the literature recommending specific screening strategies for patients with mental illness, although the vetting and update process has been ill defined. Among patients with schizophrenia, though, regardless of antipsychotic prescription status, baseline and then regular monitoring of metabolic risk parameters is recommended.17

Primary prevention. Lifestyle modification and attention to modifiable coronary risk factors are important primary prevention strategies. Dietary modifications, exercise, not smoking, and maintenance of a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) are associated with a lower risk of CAD.18,19

Lifestyle modifications can be challenging for patients with persistent mental illness, however: For example, patients with schizophrenia smoke more, eat less healthfully, and participate less in behavioral modification that targets risk factors than patients who do not have schizophrenia.20,21

According to 2012 evidence-based practice guidelines established by a collaboration that included the American College of Physicians and several cardiology and thoracic medicine societies, persons age >50 who do not have symptomatic CAD should take low-dose (75 to 100 mg/d) aspirin; the benefit of low-dose aspirin in persons at moderate or high risk of CAD is even greater. Other medications, including statins and fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive medications in combination with a statin are not clearly beneficial as primary prevention strategies across the board, although selected high-risk populations might benefit.

Regrettably, the high-risk population of persons with mental illness and whose primary care is suboptimal has not been studied. It stands to reason that these patients would especially benefit from more attentive monitoring and intervention.

Collaborative care? Although many psychiatrists do not practice in such a model, a comprehensive approach to the care of their patients, using a collaborative care strategy that includes attention to the mental health diagnosis along with medical health, can result in improved health in both domains.22 However, enlisting patients with paranoia or an inherent distrust of medications and health care providers to adhere to either a medication regimen or lifestyle modification can be challenging.

Common-sense strategies, such as creating a multidisciplinary team with the psychiatrist coordinating care and optimizing antipsychotic treatment, might provide benefit.1 Data demonstrate that patients with severe mental illness who experience acute coronary events undergo revascularization at a lower rate than their mentally heathy counterparts, despite the fact that patients with severe mental illness die at a higher rate from their CAD than patients who do not have mental illness. An important role for the psychiatrist, even in the absence of a collaborative care program, is to be an advocate for appropriate guideline-based care.23

Secondary prevention. Once a patient develops CAD, ongoing risk factor modification is important. Adherence to a therapeutic regimen that variously combines a platelet inhibitor, beta blocker, statin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is associated with improved outcomes in patients with CAD.24 Specific antiplatelet recommendations and a recommendation for single vs combination antiplatelet therapy depends on chronicity and type of revascularization in a setting of CAD.25

Summary of guideline-based recommendations

Treatment guidelines published in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse address depression, CAD screening, and specific cardiac therapies, including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, oral anticoagulants, platelet inhibitors, beta blockers, and lifestyle modification.

Primary prevention. Recommendations for treatment to prevent CAD are listed in Table 1.

Secondary prevention. Recommendations for treatment after a diagnosis of CAD are listed in Table 2.

Special considerations for psychiatric providers

You should be comfortable with patients’ use of antihypertensive therapies and familiar with the potential these agents have to interact with psychotropics; in addition, you can take a more active role in prescribing, and monitoring patients’ responses to, these medications. Provide appropriate monitoring of ACE inhibitors, statins, and beta blockers; also, provide appropriate monitoring of psychotropics in patients who take recommended cardioprotective medications.

In situations that prompt referral (such as recent MI, new symptoms of heart failure, any history of syncope or new identification of T2DM), ideally you should collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider to help enhance adherence to recommended treatment strategies. You also should employ motivational interviewing techniques and offer strategies by which patients can engage in meaningful lifestyle modification.

There are official recommendations for depression screening strategies26 and psychosocial risk screening for patients in whom CAD has been identified.27 Official screening strategies for CAD in patients with psychiatric illness have not, however, been spelled out.

Primary CAD prevention with medication is not routinely recommended for the general population, but the increased risk of CAD associated with psychiatric diagnoses (particularly schizophrenia, as well as the medications used to treat it) might warrant consideration of aggressive primary prevention strategies.28 For example, some experts recommend starting metformin to reduce the risk of T2DM in patients who have been started on olanzapine or clozapine, regardless of the baseline fasting blood glucose level.29

You should be fully informed and aware of patients’ underlying medical conditions and the medications that are recommended to treat their conditions. Ideally, an integrated care strategy or, at the least, clear communication between you and the patient’s primary care providers should be in place to avoid foreseeable problems.

Stimulants. Systematic reviews suggest an association between prescription stimulants and at least the 2 cardiovascular risk factors of elevated heart rate and blood pressure. Stimulants are not recommended, therefore, for routine use in patients who have known hypertension or CAD.30

Second-generation antipsychotics are associated with significant weight gain and development of metabolic syndrome.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding risk related to platelet inhibition and gastric effects. Risk increases with additional platelet inhibitors, such as aspirin or clopidogrel.31

Lithium is excreted solely by the kidney. Guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor-blockers for patients with CAD or T2DM, and many patients with symptomatic congestive heart failure are prescribed a diuretic; all of these classes of medications impair excretion of lithium. In a nested case-control study, 3% of observed cases of lithium toxicity were attributable to a newly initiated ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor-blocker.32 It is essential that you, and your patients taking lithium, be aware of the need to monitor the drug level frequently and be vigilant for symptoms of mild toxicity.

Beta blockers. No prospectively collected data support a association between beta blockers and depression.33 Patients with CAD should be given a trial of a beta blocker to achieve optimal medical management; because they are at increased risk of depression in the first place, all patients with CAD should undergo monitoring for depressive symptoms.

Clopidogrel is activated through the cytochrome P450 2C19 isoenzyme; medications such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine that inhibit the function of CYP2C19 can impair the effectiveness of clopidogrel.31

Other considerations. Patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic should have baseline and periodic (monthly for the first quarter, then quarterly) assessments of BMI and, after monitoring at 3 months after baseline, annual monitoring of blood pressure, the fasting glucose level, and abdominal waist circumference. Lipid levels should be monitored every 5 years9 (Table 3).

Baseline and periodic monitoring of hepatic enzymes is recommended for patients taking a statin. You, and the patient, should be alert to the possible development of muscle weakness or pain; establish a low threshold for screening for an elevated creatine kinase level, which signals rhabdomyolysis.

Case concluded

Ms. S’s psychiatrist measures her blood pressure and finds that it is 147/92 mm Hg. He uses the Pooled Cohort Equations to determine that her lifetime risk of cardiovascular event is 50% (compared with a 8% lifetime risk among a cohort in whom risk factors are optimized) and that her 10-year risk is 41% (compared with a 2.2% risk among optimized controls).

At this point, the psychiatrist starts metformin to prevent T2DM. He also starts Ms. S on a statin to prevent CAD in a setting of diagnosed T2DM.

Ms. S’s exertional dyspnea and shoulder discomfort could be associated with angina, and the physician wisely refers her for urgent evaluation. Because he is aware of the literature demonstrating decreased revascularization among patients with mental illness, he urges her other health care providers to provide her with guideline-based strategies to treat her cardiovascular disease.

Bottom Line

Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population. Symptoms characteristic of depression and schizophrenia could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors. Institute strategies for primary and secondary prevention of CAD among your patients, based on published guidelines, and be aware of, and alert for, adverse cardiac effects and an increase in risk factors for CAD from the use of psychotropics.

Related Resources

• Elderon L, Whooley MA. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(6):511-523.

• Interactive cardiovascular risk calculator developed from the Framingham Heart Study. https://www.framingham heartstudy.org/risk-functions/cardiovascular-disease/ 10-year-risk.php.

• Pooled Cohort Equations calculator. To determine estimated cardiovascular risk in comparison with peers with optimized risk factors. http://clincalc.com/cardiology/ascvd/ pooledcohort.aspx.

• To learn more about traditional cardiovascular risk factors from the Framingham Heart Study. http://www.framinghamheart study.org/risk-functions/.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Felodipine • Plendil

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heald A, Montejo AL, Millar H, et al. Management of physical health in patients with schizophrenia: practical recommendations. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S41-S45.

2. Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, et al. Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;2013:695925. doi: 10.1155/2013/695925.

3. Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick ZR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285.

4. Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Katsiki N, et al; GREACE Study Collaborative Group. The impact of smoking on cardiovascular outcomes and comorbidities in statin-treated patients with coronary artery disease: a post hoc analysis of the GREACE study. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11(5):779-784.

5. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 AACF/ AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44-e164.

6. Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):359-367.

7. Pozuelo L, Tesar G, Zhang J, et al. Depression and heart disease: what do we know, and where are we headed? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(1):59-70.

8. Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, et al. Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illnesses: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:84.

9. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

10. Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: results of the REMIT trial. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2139-2049.

11. Soares-Filho GL, Mesquita CT, Mesquita ET, et al. Panic attack triggering myocardial ischemia documented by myocardial perfusion imaging study. A case report. Int Arch Med. 2012;5(1):24.

12. Khawaja IS, Westermeyer JJ, Gajwani P, et al. Depression and coronary artery disease: the association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(1):38-51.

13. Wang G, Cui J, Wang Y, et al. Anxiety and adverse coronary artery disease outcomes in Chinese patients. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):530-536.

14. Watkins LL, Koch GG, Sherwood A, et al. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000068. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000068.

15. Chiavarino C, Rabellino D, Ardito RB, et al. Emotional coping is a better predictor of cardiac prognosis than depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(6):473-475.

16. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):512-518.

17. De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;199(2):99-105.

18. Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J, et al. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2.

19. Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rexrode KM, et al. Adherence to a low-risk, healthy lifestyle and risk of sudden cardiac death among women. JAMA. 2011;306(1):62-69.

20. Davidson M. Risk of cardiovascular disease and sudden death in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 9):5-11.

21. Dipasquale S, Pariante CM, Dazzan P, et al. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):197-207.

22. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611-2620.

23. Manderbacka K, Arffman M, Sund R, et al. How does a history of psychiatric hospital care influence access to coronary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000831. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000831.

24. Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al; REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health Registry Investigators. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):693-700.

25. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence- Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e637S-e668S.

26. Lichtman JH, Bigger T, Blumenthal JA, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; American Psychiatric Association. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768-1775.

27. Albus C, Jordan J, Herrmann-Lingen C. Screening for psychosocial risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease-recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(1):75-79.

28. Srihari VH, Phutane VH, Ozkan B, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia: defining a critical period for prevention. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1-3):64-68.

29. Brooks JO 3rd, Chang HS, Krasnykh O. Metabolic risks in older adults receiving second-generation antipsychotic medication. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):33-40.

30. Martinez-Raga J, Knecht C, Szerman N, et al. Risk of serious cardiovascular problems with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(1):15-30.

31. Andrade C. Drug interactions in the treatment of depression in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):e1475-e1477.

32. Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Kopp A, et al. Drug-induced lithium toxicity in the elderly: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):794-798.

33. Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP. Do beta blockers cause depression? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):50,51,55.

1. Heald A, Montejo AL, Millar H, et al. Management of physical health in patients with schizophrenia: practical recommendations. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S41-S45.

2. Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, et al. Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;2013:695925. doi: 10.1155/2013/695925.

3. Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick ZR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285.

4. Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Katsiki N, et al; GREACE Study Collaborative Group. The impact of smoking on cardiovascular outcomes and comorbidities in statin-treated patients with coronary artery disease: a post hoc analysis of the GREACE study. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11(5):779-784.

5. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 AACF/ AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44-e164.

6. Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):359-367.

7. Pozuelo L, Tesar G, Zhang J, et al. Depression and heart disease: what do we know, and where are we headed? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(1):59-70.

8. Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, et al. Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illnesses: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:84.

9. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

10. Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: results of the REMIT trial. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2139-2049.

11. Soares-Filho GL, Mesquita CT, Mesquita ET, et al. Panic attack triggering myocardial ischemia documented by myocardial perfusion imaging study. A case report. Int Arch Med. 2012;5(1):24.

12. Khawaja IS, Westermeyer JJ, Gajwani P, et al. Depression and coronary artery disease: the association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(1):38-51.

13. Wang G, Cui J, Wang Y, et al. Anxiety and adverse coronary artery disease outcomes in Chinese patients. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):530-536.

14. Watkins LL, Koch GG, Sherwood A, et al. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000068. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000068.

15. Chiavarino C, Rabellino D, Ardito RB, et al. Emotional coping is a better predictor of cardiac prognosis than depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(6):473-475.

16. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):512-518.

17. De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;199(2):99-105.

18. Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J, et al. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2.

19. Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rexrode KM, et al. Adherence to a low-risk, healthy lifestyle and risk of sudden cardiac death among women. JAMA. 2011;306(1):62-69.

20. Davidson M. Risk of cardiovascular disease and sudden death in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 9):5-11.

21. Dipasquale S, Pariante CM, Dazzan P, et al. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):197-207.

22. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611-2620.

23. Manderbacka K, Arffman M, Sund R, et al. How does a history of psychiatric hospital care influence access to coronary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000831. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000831.

24. Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al; REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health Registry Investigators. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):693-700.

25. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence- Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e637S-e668S.

26. Lichtman JH, Bigger T, Blumenthal JA, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; American Psychiatric Association. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768-1775.

27. Albus C, Jordan J, Herrmann-Lingen C. Screening for psychosocial risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease-recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(1):75-79.

28. Srihari VH, Phutane VH, Ozkan B, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia: defining a critical period for prevention. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1-3):64-68.

29. Brooks JO 3rd, Chang HS, Krasnykh O. Metabolic risks in older adults receiving second-generation antipsychotic medication. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):33-40.

30. Martinez-Raga J, Knecht C, Szerman N, et al. Risk of serious cardiovascular problems with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(1):15-30.

31. Andrade C. Drug interactions in the treatment of depression in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):e1475-e1477.

32. Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Kopp A, et al. Drug-induced lithium toxicity in the elderly: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):794-798.

33. Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP. Do beta blockers cause depression? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):50,51,55.