User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Two vastly underutilized interventions can improve schizophrenia outcomes

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2011/02/two-vastly-underutilized-interventions.html#comments

Many psychiatrists would agree that schizophrenia is the most devastating psychiatric brain disease. Its disabling effects result in stigma, unemployment, poverty, loneliness, homelessness, victimization, incarceration, malnutrition, infections, social isolation, ostracism, discrimination, suicide, poor health, medical neglect, and early death.

The consequences of schizophrenia are in many ways more malignant than those of cancer, where sympathy, prompt medical care, and preservation of friends and employment are assured. Also, unlike schizophrenia patients, persons with cancer are never hauled to jail, even when a slow-growing brain tumor causes erratic or violent behavior.

The outcome of schizophrenia has not improved much since patients were “freed” from state hospitals before the psychopharmacology era. Despite the availability of antipsychotics that can control delusions and hallucinations, few persons with schizophrenia achieve remission, let alone recovery. Although negative symptoms and cognitive deficits remain untreatable, the quality of life for persons with schizophrenia can be far less miserable if psychotic symptoms are fully remitted. So why do so many patients with schizophrenia suffer continuous or episodic psychosis that renders their lives a living hell and leads them to inexorable clinical, social, and functional deterioration?

Based on 3 decades of clinical and research work with thousands of patients afflicted with schizophrenia, I have observed that most psychiatrists are not exploiting 2 treatment options that could effectively alleviate continuous or relapsing psychosis. Let me elaborate:

- Continuous, unabated psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and thought derailment) implies either refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia. This means that several antipsychotic trials already have failed to suppress psychotic symptoms. Only 1 drug has been proven to help such patients: clozapine. It was FDA-approved for refractory schizophrenia 22 years ago, and many studies—including the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial—show that it also is superior to other antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Yet while about 30% to 35% of patients have refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia, only one-sixth of that eligible pool receive clozapine. Reasons include the “hassle” of monitoring, the fear of agranulocytosis (which is rare), and concern about serious side effects. As a result, hundreds of thousands of patients suffer needlessly because they have not received clozapine (full response may take 6 to 12 months in some patients, but only 3 months in others).

- For patients whose delusions and hallucinations do respond to nonclozapine antipsychotics, psychotic episodes are most likely caused by nonadherence to oral medications. All psychiatrists are aware that partial or complete nonadherence is ubiquitous in schizophrenia for multiple reasons, including lack of insight about being ill and needing treatment, suspiciousness (positive symptoms) about drugs, amotivation and avolition (negative symptoms), poor memory or planning ability (cognitive deficits), and toxic effects of alcohol and drugs. Therefore, many psychotic relapses occur needlessly because of inevitable nonadherence with oral medications. In my clinical estimate, this occurs in 50% to 60% of patients who had responded well to oral antipsychotics in the past. The tragic consequences of recurrent relapses is not only re-experiencing the anguish of reality-shattering psychotic states, but also progressive brain atrophy resulting from the “neurotoxic” effects of psychosis, and, unfortunately, progressive development of treatment resistance with each relapse.

The most logical solution to avoid psychotic relapses resulting from nonadherence is long-acting injectable (depot) antipsychotics, which have a large body of data (including FDA registration trials) documenting successful relapse prevention. It is incomprehensible why long-acting formulations are not used in at least 30% to 40% of patients instead of the 6% to 8% who currently receive them. They also should be given to all schizophrenia patients incarcerated for violent acts. Furthermore, there is no reason not to use injectable formulations early in the illness course—after 1 or 2 relapses—to halt or prevent the clinical and functional deterioration that occurs with multiple relapses. In my experience, the stabilization and full remission that occur after 18 to 24 months of continuous adherence with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic can be remarkable and gratifying to patients, families, and psychiatrists.

In summary, intensified research is needed to discover the next generation of pharmacotherapeutic agents that can treat all symptom domains of schizophrenia (positive, negative, cognitive, mood, and substance use). In the meantime, a wider use of those 2 available interventions—clozapine in refractory and treatment-resistant patients and long-acting injectable antipsychotics in nonadherent patients—can make a palpable impact on improving clinical and functional outcomes of patients suffering with schizophrenia. These 2 interventions might make a significant dent in the atrociously high rate of incarceration because of psychosis-induced illegal behaviors. The financial savings in hospitalization and forensic costs can be substantial. But most important, preventing psychosis and incarceration would mean a measurably better life for patients.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2011/02/two-vastly-underutilized-interventions.html#comments

Many psychiatrists would agree that schizophrenia is the most devastating psychiatric brain disease. Its disabling effects result in stigma, unemployment, poverty, loneliness, homelessness, victimization, incarceration, malnutrition, infections, social isolation, ostracism, discrimination, suicide, poor health, medical neglect, and early death.

The consequences of schizophrenia are in many ways more malignant than those of cancer, where sympathy, prompt medical care, and preservation of friends and employment are assured. Also, unlike schizophrenia patients, persons with cancer are never hauled to jail, even when a slow-growing brain tumor causes erratic or violent behavior.

The outcome of schizophrenia has not improved much since patients were “freed” from state hospitals before the psychopharmacology era. Despite the availability of antipsychotics that can control delusions and hallucinations, few persons with schizophrenia achieve remission, let alone recovery. Although negative symptoms and cognitive deficits remain untreatable, the quality of life for persons with schizophrenia can be far less miserable if psychotic symptoms are fully remitted. So why do so many patients with schizophrenia suffer continuous or episodic psychosis that renders their lives a living hell and leads them to inexorable clinical, social, and functional deterioration?

Based on 3 decades of clinical and research work with thousands of patients afflicted with schizophrenia, I have observed that most psychiatrists are not exploiting 2 treatment options that could effectively alleviate continuous or relapsing psychosis. Let me elaborate:

- Continuous, unabated psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and thought derailment) implies either refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia. This means that several antipsychotic trials already have failed to suppress psychotic symptoms. Only 1 drug has been proven to help such patients: clozapine. It was FDA-approved for refractory schizophrenia 22 years ago, and many studies—including the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial—show that it also is superior to other antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Yet while about 30% to 35% of patients have refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia, only one-sixth of that eligible pool receive clozapine. Reasons include the “hassle” of monitoring, the fear of agranulocytosis (which is rare), and concern about serious side effects. As a result, hundreds of thousands of patients suffer needlessly because they have not received clozapine (full response may take 6 to 12 months in some patients, but only 3 months in others).

- For patients whose delusions and hallucinations do respond to nonclozapine antipsychotics, psychotic episodes are most likely caused by nonadherence to oral medications. All psychiatrists are aware that partial or complete nonadherence is ubiquitous in schizophrenia for multiple reasons, including lack of insight about being ill and needing treatment, suspiciousness (positive symptoms) about drugs, amotivation and avolition (negative symptoms), poor memory or planning ability (cognitive deficits), and toxic effects of alcohol and drugs. Therefore, many psychotic relapses occur needlessly because of inevitable nonadherence with oral medications. In my clinical estimate, this occurs in 50% to 60% of patients who had responded well to oral antipsychotics in the past. The tragic consequences of recurrent relapses is not only re-experiencing the anguish of reality-shattering psychotic states, but also progressive brain atrophy resulting from the “neurotoxic” effects of psychosis, and, unfortunately, progressive development of treatment resistance with each relapse.

The most logical solution to avoid psychotic relapses resulting from nonadherence is long-acting injectable (depot) antipsychotics, which have a large body of data (including FDA registration trials) documenting successful relapse prevention. It is incomprehensible why long-acting formulations are not used in at least 30% to 40% of patients instead of the 6% to 8% who currently receive them. They also should be given to all schizophrenia patients incarcerated for violent acts. Furthermore, there is no reason not to use injectable formulations early in the illness course—after 1 or 2 relapses—to halt or prevent the clinical and functional deterioration that occurs with multiple relapses. In my experience, the stabilization and full remission that occur after 18 to 24 months of continuous adherence with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic can be remarkable and gratifying to patients, families, and psychiatrists.

In summary, intensified research is needed to discover the next generation of pharmacotherapeutic agents that can treat all symptom domains of schizophrenia (positive, negative, cognitive, mood, and substance use). In the meantime, a wider use of those 2 available interventions—clozapine in refractory and treatment-resistant patients and long-acting injectable antipsychotics in nonadherent patients—can make a palpable impact on improving clinical and functional outcomes of patients suffering with schizophrenia. These 2 interventions might make a significant dent in the atrociously high rate of incarceration because of psychosis-induced illegal behaviors. The financial savings in hospitalization and forensic costs can be substantial. But most important, preventing psychosis and incarceration would mean a measurably better life for patients.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2011/02/two-vastly-underutilized-interventions.html#comments

Many psychiatrists would agree that schizophrenia is the most devastating psychiatric brain disease. Its disabling effects result in stigma, unemployment, poverty, loneliness, homelessness, victimization, incarceration, malnutrition, infections, social isolation, ostracism, discrimination, suicide, poor health, medical neglect, and early death.

The consequences of schizophrenia are in many ways more malignant than those of cancer, where sympathy, prompt medical care, and preservation of friends and employment are assured. Also, unlike schizophrenia patients, persons with cancer are never hauled to jail, even when a slow-growing brain tumor causes erratic or violent behavior.

The outcome of schizophrenia has not improved much since patients were “freed” from state hospitals before the psychopharmacology era. Despite the availability of antipsychotics that can control delusions and hallucinations, few persons with schizophrenia achieve remission, let alone recovery. Although negative symptoms and cognitive deficits remain untreatable, the quality of life for persons with schizophrenia can be far less miserable if psychotic symptoms are fully remitted. So why do so many patients with schizophrenia suffer continuous or episodic psychosis that renders their lives a living hell and leads them to inexorable clinical, social, and functional deterioration?

Based on 3 decades of clinical and research work with thousands of patients afflicted with schizophrenia, I have observed that most psychiatrists are not exploiting 2 treatment options that could effectively alleviate continuous or relapsing psychosis. Let me elaborate:

- Continuous, unabated psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and thought derailment) implies either refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia. This means that several antipsychotic trials already have failed to suppress psychotic symptoms. Only 1 drug has been proven to help such patients: clozapine. It was FDA-approved for refractory schizophrenia 22 years ago, and many studies—including the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial—show that it also is superior to other antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Yet while about 30% to 35% of patients have refractory or treatment-resistant schizophrenia, only one-sixth of that eligible pool receive clozapine. Reasons include the “hassle” of monitoring, the fear of agranulocytosis (which is rare), and concern about serious side effects. As a result, hundreds of thousands of patients suffer needlessly because they have not received clozapine (full response may take 6 to 12 months in some patients, but only 3 months in others).

- For patients whose delusions and hallucinations do respond to nonclozapine antipsychotics, psychotic episodes are most likely caused by nonadherence to oral medications. All psychiatrists are aware that partial or complete nonadherence is ubiquitous in schizophrenia for multiple reasons, including lack of insight about being ill and needing treatment, suspiciousness (positive symptoms) about drugs, amotivation and avolition (negative symptoms), poor memory or planning ability (cognitive deficits), and toxic effects of alcohol and drugs. Therefore, many psychotic relapses occur needlessly because of inevitable nonadherence with oral medications. In my clinical estimate, this occurs in 50% to 60% of patients who had responded well to oral antipsychotics in the past. The tragic consequences of recurrent relapses is not only re-experiencing the anguish of reality-shattering psychotic states, but also progressive brain atrophy resulting from the “neurotoxic” effects of psychosis, and, unfortunately, progressive development of treatment resistance with each relapse.

The most logical solution to avoid psychotic relapses resulting from nonadherence is long-acting injectable (depot) antipsychotics, which have a large body of data (including FDA registration trials) documenting successful relapse prevention. It is incomprehensible why long-acting formulations are not used in at least 30% to 40% of patients instead of the 6% to 8% who currently receive them. They also should be given to all schizophrenia patients incarcerated for violent acts. Furthermore, there is no reason not to use injectable formulations early in the illness course—after 1 or 2 relapses—to halt or prevent the clinical and functional deterioration that occurs with multiple relapses. In my experience, the stabilization and full remission that occur after 18 to 24 months of continuous adherence with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic can be remarkable and gratifying to patients, families, and psychiatrists.

In summary, intensified research is needed to discover the next generation of pharmacotherapeutic agents that can treat all symptom domains of schizophrenia (positive, negative, cognitive, mood, and substance use). In the meantime, a wider use of those 2 available interventions—clozapine in refractory and treatment-resistant patients and long-acting injectable antipsychotics in nonadherent patients—can make a palpable impact on improving clinical and functional outcomes of patients suffering with schizophrenia. These 2 interventions might make a significant dent in the atrociously high rate of incarceration because of psychosis-induced illegal behaviors. The financial savings in hospitalization and forensic costs can be substantial. But most important, preventing psychosis and incarceration would mean a measurably better life for patients.

Not all mood swings are bipolar disorder

M, age 13, is referred by her pediatrician with the chief complaint of “severe mood swings, rule out bipolar disorder (BD).” In the past she was treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with stimulants with mixed results. M’s parents are concerned about her “flipping out” whenever she is asked to do something she does not want to do. Her mother has a history of depression and anxiety; her father had a “drinking problem.” There is no history of BD in her first- or second-degree relatives. Are M’s rapid mood swings a sign of BD or another disorder?

The differential diagnosis of “mood swings” is important because they are a common presenting symptom of many children and adolescents with mood and behavioral disorders. Mood swings often occur in children and adolescents with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), developmental disorders, depressive disorders, BD, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorders. Mood swings are analogous to a fever in pediatrics—they indicate something potentially is wrong with the patient, but are not diagnostic as an isolated symptom.

Mood swings in children are common, nonspecific symptoms that more often are a sign of anxiety or behavioral disorders than BD. This article discusses the differential diagnosis of mood swings in children and adolescents and how to best screen and diagnose these patients.

What are ‘mood swings’?

Mood swings is a popular term that is nonspecific and not part of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for BD. The complaint of “mood swings” may reflect severe mood lability of pediatric patients with BD. This mood lability is best described by the Kiddie-Mania Rating Scale (K-MRS) developed by Axelson and colleagues as “rapid mood variation with several mood states within a brief period of time which appears internally driven without regard to the circumstance.”1 On K-MRS mood lability items, children with mania typically score:

- Moderate—many mood changes throughout the day, can vary from elevated mood to anger to sadness within a few hours; changes in mood are clearly out of proportion to circumstances and cause impairment in functioning

- Severe—rapid mood swings nearly all of the time, with mood intensity greatly out of proportion to circumstances

- Extreme—constant, explosive variability in mood, several mood changes occurring within minutes, difficult to identify a particular mood, changes in mood radically out of proportion to circumstances.

Patients with BD typically exhibit what is best described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from 1 extreme to another.2 An example of this would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours and then later in the day becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle. BD patients also will exhibit other symptoms of mania during these mood cycling periods.

Rapid cycling is a DSM-IV course specifier that indicates ≥4 mood episodes per year in patients with BD with a typical course of mania or hypomania followed by depression, or vice versa.3 The episodes must be demarcated by full or partial remission that lasts ≥2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity. In the past, children with frequent mood swings were described incorrectly as “rapid cycling,” but this term has been dropped because it engenders confusion between adult and pediatric BD phenomenology.2

A more precise method of describing mood symptoms in a child or adolescent is to use the FIND criteria, which include:4

- Frequency of symptoms per week

- Intensity of mood symptoms

- Number of mood cycles per day

- Duration of symptoms per day.

Visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com to view a table that outlines what to look for when using the FIND criteria to evaluate common pediatric psychiatric disorders that include mood swings. Table 1

describes clinical characteristics and tools and resources used to differentiate these and other disorders.4

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of psychiatric disorders that often feature mood swings

| Disorder | Clinical description | Useful tools/resources |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Chronic symptoms of hyperactivity, distractibility, impulsivity, poor attentional skills, disorganization | Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) |

| ODD | Chronic symptoms of oppositionality, negativity; short, frequent mood swings in response to being asked to do something they do not want to do | CPRS-R:L |

| Anxiety disorders | Excessive ‘worry,’ difficulty with transitions, increased mood swings during stressful periods, psychosomatic symptoms | Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders |

| ARND | History of exposure to alcohol in-utero; mild dysmorphia, attentional, mood, and executive functioning problems | National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome |

| Bipolar disorder | In children: clustering together of episodes or ‘mini-episodes’ (several days) of increased energy, decreased need for sleep, increased mood cycling, pressured speech, etc. In adolescents: depressive episodes with episodes of hypomania or mania | Mood Disorders Questionnaire Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Mania Rating Scale |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ARND: alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder | ||

| Source: Reference 4 | ||

Mood swings: A chart review

We recently completed a retrospective chart review of 100 patients consecutively referred to our pediatric mood disorders clinic for evaluation of “mood swings, rule out BD.” These patients were self-referred, referred by a psychiatrist for a second opinion, or referred by their primary care physician. The mean age of these patients was 8±2.8 years and 68% were male.

Two experienced clinicians (RAK and EM) interviewed each patient and their caregivers and reviewed results of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L)5 and other outside information.

Figure 1 illustrates these patients’ diagnoses. Diagnoses for each of these disorders were made using DSM-IV-TR criteria.3

The most common diagnoses among patients with the chief complaint of mood swings were ADHD (39%); ODD with ADHD (15%); an anxiety disorder, usually generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (15%); BD (12%); and a secondary mood disorder, usually fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (10%). We were surprised at how often ADHD, ODD, and anxiety disorders were found to be responsible for these patients’ mood swings and how frequently the referring clinician did not recognize these disorders. In the following sections, we discuss each of these disorders and how they differ from BD.

Figure 1 Underlying diagnoses of 100 children/adolescents referred for ‘mood swings’

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder; PDD: pervasive developmental disorder

ADHD and ODD

In our sample, patients with undiagnosed ADHD made up the largest group of those with frequent mood swings. ADHD inattentive type was missed frequently in adolescent girls who still had behavioral aspects of ADHD, including impulsivity and aggression.6

The CPRS-R:L is useful for screening and diagnosing children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD. It contains 80 items, can be used in males and females and patients age 3 to 17, and has validated norms by age and sex.5 It takes parents approximately 10 minutes to fill out this questionnaire and the results can be scored by hand. The CPRS-R:L includes the following scales: oppositional; cognitive problems/inattention; hyperactivity; anxious-shy; perfectionism; social problems; psychosomatic; Connors’ global index; DSM-IV symptom subscales; and an ADHD index. Patients with mood swings and ADHD combined typically score >2 standard deviations above their age/sex mean on the CPRS-R:L hyperactivity scale, Connors’ Global Index, and ADHD index.5

A common childhood disorder, ODD has multiple etiologies.7 The first DSM-IV criteria for ODD is “often loses temper”3—essentially mood swings that often are expressed behaviorally as anger and at times as aggressive outbursts.

Dodge and Cole8 categorized aggression as reactive (impulsivity with a high affective valence) or proactive (characterized by low arousal and premeditation, ie, predatory conduct disorder). Reactive aggression typically is an angry defensive response to frustration, threat, or provocation, whereas proactive aggression is deliberate, coercive behavior often used to obtain a goal.9 Reactive aggression is common among children with ADHD and ODD and typically begins as a mood swing that escalates into reactive aggressive behavior. In a study of 268 consecutively referred children and adolescents with ADHD and 100 community controls, Connor et al10 found significantly more reactive than proactive forms of aggression in ADHD patients.

It can be difficult to differentiate the moods swings and symptoms of ODD from those of pediatric BD. Mick et al11 found that severe irritability may be a diagnostic indicator of BD in children with ADHD. Using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (epidemiologic version) structured diagnostic interview,12 they evaluated 274 children (mean age 10.8±3.2) with ADHD; 37% had no comorbid mood disorder, 36% had ADHD with depression, and 11% had ADHD with BD. Researchers characterized 3 types of irritability in these patients:

- ODD-type irritability characterized by a low frustration tolerance that is seen in ODD

- Mad/cranky irritability found in depressive disorders

- Super-angry/grouchy/cranky irritability with frequent, prolonged, and largely unprovoked anger episodes and characteristics of mania.

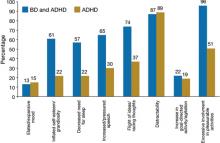

ODD-type irritability was common among all ADHD patients, was the least impairing type of irritability, and did not increase the risk of a mood disorder. Mad/cranky irritability was common only in children with ADHD and a mood disorder (depression or BD), was more impairing than ODD-type irritability, and was most predictive of unipolar depression. Super-angry/grouchy/cranky irritability was common only among children with ADHD and BD (77%), was the most impairing, and was predictive of both unipolar depression and BD. The type of irritability and clustering of DSM-IV manic symptoms best differentiated ADHD subjects from those with ADHD and BD. Figure 2 illustrates symptoms that differentiated patients with ADHD from those with ADHD and comorbid BD.11

A review of pharmacotherapy for aggression in children found the largest effects for methylphenidate for aggression in ADHD (mean effect size=0.9, combined N=844).13 Our clinical experience has been that pediatric patients with ADHD or ODD with ADHD often have high levels of reactive aggression that presents as mood swings, and aggressively treating ADHD often results in improved mood and other ADHD symptoms.

Figure 2 Symptoms that differentiate BD from BD with comorbid ADHD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

Source: Reference 11

Anxiety disorders

The estimated prevalence of child and adolescent anxiety disorders is 10% to 20%14; in our sample the prevalence was 15%. These disorders include GAD, separation anxiety disorder, social phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Often, children with GAD worry excessively and become upset during transitions when things don’t proceed as they expect, with resultant angry outbursts and mood swings. Mood swings and difficulty sleeping are common in children with anxiety disorders or BD. Anxiety disorders often will be missed unless specific triggers of the mood swings or angry outbursts—as well as differentiating symptoms such as excessive fear, worry, and psychosomatic symptoms—are assessed.

In our clinical experience, simply asking a child if he or she is anxious is not sufficient to uncover an anxiety disorder. Although the CPRS-L:R will screen for anxiety disorders, we have found that the Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) developed by Birmaher et al15 is more specific. This tool can be used in patients age ≥8. The parent and child versions of the SCARED contain 41 items that measure 5 factors:

- general anxiety

- separation anxiety

- social phobia

- school phobia

- physical symptoms of anxiety.

The SCARED takes 5 minutes to fill out and is available in parent and child versions.

Secondary mood disorders

Many patients in our sample had a mood disorder secondary to the neurologic effects of alcohol on the developing brain. For more about maternal alcohol use, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, and mood swings, visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

What BD looks like in children

In our sample, 12% of patients referred for mood swings were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder (BDI), bipolar II disorder (BDII), or bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified (BD-NOS). In the United States, lifetime prevalence of BDI and BDII in adolescents age 13 to 17 is 2.9%.16 No large epidemiologic studies have looked at the lifetime prevalence of BD in children age <13.

How often a clinician sees BD in children and adolescents largely depends on the type of setting in which he or she practices. Although in the general population BD is relatively rare compared with other childhood psychiatric disorders, on child/adolescent inpatient units it is common to find that 30% to 40% of patients have BD.17

The best longitudinal study to date of the phenomenology, comorbidity, and outcome of BD in children and adolescents is the National Institute of Mental Health-funded Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study (COBY).18 In this ongoing, longitudinal study, 413 youths (age 7 to 17) with BDI (N=244), BDII (N=28), or BD-NOS (N=141) were rigorously diagnosed using state-of-the-art measures, including the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present version19 and re-evaluated every 9.4 months for 4 years. When organizing this study, investigators found that DSM-IV criteria for BD-NOS were too vague to be useful and developed their own criteria (Table 2).18

For BDI patients in the COBY study, the mean age of onset for bipolar symptoms was 9.0±4.1 years and the mean duration of illness was 4.4±3.1 years. Researchers reported that at the 4-year assessment approximately 70% of patients with BD recovered from their index episode, and 50% had at least 1 syndromal recurrence, particularly depressive episodes.20 Analyses of these patients’ weekly mood symptoms showed that they had syndromal or subsyndromal symptoms with numerous changes in symptoms and shifts of mood polarity 60% of the time, and psychosis 3% of the time. During this study, 20% of BDII patients progressed to BDI, and 25% of BD-NOS patients converted to BDI or BDII.

Further analysis of the COBY data revealed that onset of mood symptoms preceded onset of clear bipolar episodes by an average of 1.0±1.7 years. Depression was the most common initial and most frequent episode for adolescents; mood lability was seen more often in childhood-onset and adolescents with early-onset BD. Depressed children had more severe irritability than depressed adolescents, and older age was associated with more severe and typical mood symptomatology.21

The clinical picture of a child with BD that emerges from the COBY study is:

- a fairly young child with the onset of mood symptoms between age 5 to 12

- subsyndromal and less frequently clear syndromal episodes

- primarily mixed and depressed symptoms with rapid mood cycles during these episodes.22

It is clear that there is a spectrum of bipolar disorders in children and adolescents with varying degrees of symptom expression and children differ from adolescents and adults in their initial presentation of BD.

Table 2

COBY criteria for bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified

| Presence of clinically relevant bipolar symptoms that do not fulfill DSM-IV criteria for BDI or BDII |

| In addition, patients are required to have elevated mood plus 2 associated DSM-IV symptoms or irritable mood plus 3 DSM-IV associated symptoms, along with a change in level of functioning |

| Duration of a minimum of 4 hours within a 24-hour period |

| At least 4 cumulative lifetime days meeting the criteria |

| BDI: bipolar I disorder; BDII: bipolar II disorder; COBY: Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study |

| Source: Reference 18 |

Related Resources

- Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling RL, et al. Clinical manual for management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Miklowitz DJ, Cicchetti D, eds. Understanding bipolar disorder: a developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

Drug Brand Name

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta, others

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch receives grant/research support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health and is a consultant to AstraZeneca, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and the REACH Foundation.

Dr. Delgado and Ms. Monroe report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Table

FIND criteria of disorders found to cause mood swings

| Criteria | BDI | BP-NOS | ODD | GAD | ARND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of symptoms/week | 7 days (more days than not in an average week) | 2 to 3 days/week | Daily (chronic) irritability and mood swings precipitated by ‘not getting their way’ | Greatest during times of change/stress | Daily |

| Intensity of symptoms | Severe—parents often are afraid to take the child out in public because of mood symptoms | Moderate | Mild/moderate | Mild/moderate when stressed | Mild/moderate |

| Number of mood cycles/day | Daily cycles of euphoria and depression | 3 to 4 | 5 to 10 | 2 to 3 | 8 to 10 |

| Duration of symptoms/day | Euphoria: 30 to 60 minutes Depression: 30 minutes to 6 hours | 4 hours total/day of mood symptoms | Short; 5 to 10 minutes | Short; 5 to 10 minutes | Short; 5 to 10 minutes |

| ARND: alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; BDI: bipolar I disorder; BD-NOS: bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder | |||||

| Source: Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling RL, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008 | |||||

Even small amounts of alcohol use by a pregnant woman can impact her child’s development. In a controlled study examining drinking behavior of 12,678 pregnant women and the effect this had on their children, Sayel et ala found that <1 drink per week during the first trimester was clinically significant for mental health problems in girls, measured at age 4 and 8, when using parent or teacher report.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder describes the range of effects that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. These disorders include fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD).

FAS. Individuals with FAS have a distinct pattern of facial abnormalities, growth deficiency, and evidence of CNS dysfunction. Characteristic facial abnormalities may include a smooth philtrum, thin upper lip, upturned nose, flat nasal bridge and midface, epicanthal folds, small palpebral fissures, and small head circumference. Growth deficiency begins in-utero and continues throughout childhood and into adulthood. CNS abnormalities can include impaired brain growth or abnormal structure, manifested differently depending on age.

ARND. Many individuals affected by alcohol exposure before birth do not have the characteristic facial abnormalities and growth retardation identified with full FAS, yet have significant brain and behavioral impairments. Individuals with ARND have either the facial anomalies, growth retardation, and other physical abnormalities, or a complex pattern of behavioral or cognitive abnormalities inconsistent with developmental level and unexplained by genetic background or environmental conditions (ie, poor impulse control, language deficits, problems with abstraction, mathematical and social perception deficits, learning problems, and impairment in attention, memory, or judgment).b

ARBD. Persons with ARBD have malformations of the skeletal and major organ systems, such as cardiac or renal abnormalities.

Comorbid psychiatric conditions in children with prenatal alcohol exposure are 5 to 16 times more prevalent than in the general population; these children are 38% more likely to have an anger disorder.c O’Connor and Paleyd found that “…mood disorder symptoms were significantly higher for children with parental alcohol exposure compared to children without exposure.” Children with ARND are treated symptomatically depending upon which deficits and behaviors they exhibit.e

References

a. Sayal K, Heron J, Golding J, et al. Binge pattern of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and childhood mental health outcomes: longitudinal population-based study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e289-296.

b. Warren KR, Foudin LL. Alcohol-related birth defects—the past, present, and future. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(3):153-158.

c. Burd L, Klug MG, Martsolf JT, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome: neuropsychiatric phenomics. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25(6):697-705.

d. O’Connor MJ, Paley B. Psychiatric conditions associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):225-234.

e. Paley B, O’Connor MJ. Intervention for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: treatment approaches and case management. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):258-267.

1. Axelson D, Birmaher BJ, Brent D, et al. A preliminary study of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children mania rating scale for children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(4):463-470.

2. Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(1 Pt 2):194-214.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling RL, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008.

5. Conners CK. Conners’ Parent Rating Scale Long Form (CPRS-R:L) North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1997.

6. Martel MM. Research review: a new perspective on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: emotion dysregulation and trait models. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1042-1051.

7. Steiner H, Remsing L. and the Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(1):126-141.

8. Dodge KA, Cole JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(6):1146-1158.

9. Connor DF, Steingard RJ, Cunningham JA, et al. Proactive and reactive aggression in referred children and adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(2):129-136.

10. Connor DF, Chartier KG, Preen EC, et al. Impulsive aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: symptom severity, co-morbidity, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subtype. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(2):119-126.

11. Mick E, Spencer T, Wozniak J, et al. Heterogeneity of irritability in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subjects with and without mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(7):576-582.

12. Orvaschel H. Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders Schedule for children—Epidemiological Version (KSADS-E). Fort Lauderdale, FL: Nova Southeastern University; 1995.

13. Pappadopulos E, Woolston S, Chait A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect size. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):27-39.

14. Achenbach TM, Howell CT, McConaughy SH, et al. Six-year predictors of problems in a national sample: IV. Young adult signs of disturbance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(7):718-727.

15. Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

16. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980-989.

17. Youngstrom EA, Duax J. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, part I: base rate and family history. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(7):712-717.

18. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):175-183.

19. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980-988.

20. Birmaher B, Axelson D. Course and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a review of the existing literature. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(4):1023-1035.

21. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Comparison of manic and depressive symptoms between children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(1):52-62.

22. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795-804.

M, age 13, is referred by her pediatrician with the chief complaint of “severe mood swings, rule out bipolar disorder (BD).” In the past she was treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with stimulants with mixed results. M’s parents are concerned about her “flipping out” whenever she is asked to do something she does not want to do. Her mother has a history of depression and anxiety; her father had a “drinking problem.” There is no history of BD in her first- or second-degree relatives. Are M’s rapid mood swings a sign of BD or another disorder?

The differential diagnosis of “mood swings” is important because they are a common presenting symptom of many children and adolescents with mood and behavioral disorders. Mood swings often occur in children and adolescents with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), developmental disorders, depressive disorders, BD, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorders. Mood swings are analogous to a fever in pediatrics—they indicate something potentially is wrong with the patient, but are not diagnostic as an isolated symptom.

Mood swings in children are common, nonspecific symptoms that more often are a sign of anxiety or behavioral disorders than BD. This article discusses the differential diagnosis of mood swings in children and adolescents and how to best screen and diagnose these patients.

What are ‘mood swings’?

Mood swings is a popular term that is nonspecific and not part of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for BD. The complaint of “mood swings” may reflect severe mood lability of pediatric patients with BD. This mood lability is best described by the Kiddie-Mania Rating Scale (K-MRS) developed by Axelson and colleagues as “rapid mood variation with several mood states within a brief period of time which appears internally driven without regard to the circumstance.”1 On K-MRS mood lability items, children with mania typically score:

- Moderate—many mood changes throughout the day, can vary from elevated mood to anger to sadness within a few hours; changes in mood are clearly out of proportion to circumstances and cause impairment in functioning

- Severe—rapid mood swings nearly all of the time, with mood intensity greatly out of proportion to circumstances

- Extreme—constant, explosive variability in mood, several mood changes occurring within minutes, difficult to identify a particular mood, changes in mood radically out of proportion to circumstances.

Patients with BD typically exhibit what is best described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from 1 extreme to another.2 An example of this would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours and then later in the day becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle. BD patients also will exhibit other symptoms of mania during these mood cycling periods.

Rapid cycling is a DSM-IV course specifier that indicates ≥4 mood episodes per year in patients with BD with a typical course of mania or hypomania followed by depression, or vice versa.3 The episodes must be demarcated by full or partial remission that lasts ≥2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity. In the past, children with frequent mood swings were described incorrectly as “rapid cycling,” but this term has been dropped because it engenders confusion between adult and pediatric BD phenomenology.2

A more precise method of describing mood symptoms in a child or adolescent is to use the FIND criteria, which include:4

- Frequency of symptoms per week

- Intensity of mood symptoms

- Number of mood cycles per day

- Duration of symptoms per day.

Visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com to view a table that outlines what to look for when using the FIND criteria to evaluate common pediatric psychiatric disorders that include mood swings. Table 1

describes clinical characteristics and tools and resources used to differentiate these and other disorders.4

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of psychiatric disorders that often feature mood swings

| Disorder | Clinical description | Useful tools/resources |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Chronic symptoms of hyperactivity, distractibility, impulsivity, poor attentional skills, disorganization | Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) |

| ODD | Chronic symptoms of oppositionality, negativity; short, frequent mood swings in response to being asked to do something they do not want to do | CPRS-R:L |

| Anxiety disorders | Excessive ‘worry,’ difficulty with transitions, increased mood swings during stressful periods, psychosomatic symptoms | Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders |

| ARND | History of exposure to alcohol in-utero; mild dysmorphia, attentional, mood, and executive functioning problems | National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome |

| Bipolar disorder | In children: clustering together of episodes or ‘mini-episodes’ (several days) of increased energy, decreased need for sleep, increased mood cycling, pressured speech, etc. In adolescents: depressive episodes with episodes of hypomania or mania | Mood Disorders Questionnaire Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Mania Rating Scale |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ARND: alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder | ||

| Source: Reference 4 | ||

Mood swings: A chart review

We recently completed a retrospective chart review of 100 patients consecutively referred to our pediatric mood disorders clinic for evaluation of “mood swings, rule out BD.” These patients were self-referred, referred by a psychiatrist for a second opinion, or referred by their primary care physician. The mean age of these patients was 8±2.8 years and 68% were male.

Two experienced clinicians (RAK and EM) interviewed each patient and their caregivers and reviewed results of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L)5 and other outside information.

Figure 1 illustrates these patients’ diagnoses. Diagnoses for each of these disorders were made using DSM-IV-TR criteria.3

The most common diagnoses among patients with the chief complaint of mood swings were ADHD (39%); ODD with ADHD (15%); an anxiety disorder, usually generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (15%); BD (12%); and a secondary mood disorder, usually fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (10%). We were surprised at how often ADHD, ODD, and anxiety disorders were found to be responsible for these patients’ mood swings and how frequently the referring clinician did not recognize these disorders. In the following sections, we discuss each of these disorders and how they differ from BD.

Figure 1 Underlying diagnoses of 100 children/adolescents referred for ‘mood swings’

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder; PDD: pervasive developmental disorder

ADHD and ODD

In our sample, patients with undiagnosed ADHD made up the largest group of those with frequent mood swings. ADHD inattentive type was missed frequently in adolescent girls who still had behavioral aspects of ADHD, including impulsivity and aggression.6

The CPRS-R:L is useful for screening and diagnosing children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD. It contains 80 items, can be used in males and females and patients age 3 to 17, and has validated norms by age and sex.5 It takes parents approximately 10 minutes to fill out this questionnaire and the results can be scored by hand. The CPRS-R:L includes the following scales: oppositional; cognitive problems/inattention; hyperactivity; anxious-shy; perfectionism; social problems; psychosomatic; Connors’ global index; DSM-IV symptom subscales; and an ADHD index. Patients with mood swings and ADHD combined typically score >2 standard deviations above their age/sex mean on the CPRS-R:L hyperactivity scale, Connors’ Global Index, and ADHD index.5

A common childhood disorder, ODD has multiple etiologies.7 The first DSM-IV criteria for ODD is “often loses temper”3—essentially mood swings that often are expressed behaviorally as anger and at times as aggressive outbursts.

Dodge and Cole8 categorized aggression as reactive (impulsivity with a high affective valence) or proactive (characterized by low arousal and premeditation, ie, predatory conduct disorder). Reactive aggression typically is an angry defensive response to frustration, threat, or provocation, whereas proactive aggression is deliberate, coercive behavior often used to obtain a goal.9 Reactive aggression is common among children with ADHD and ODD and typically begins as a mood swing that escalates into reactive aggressive behavior. In a study of 268 consecutively referred children and adolescents with ADHD and 100 community controls, Connor et al10 found significantly more reactive than proactive forms of aggression in ADHD patients.

It can be difficult to differentiate the moods swings and symptoms of ODD from those of pediatric BD. Mick et al11 found that severe irritability may be a diagnostic indicator of BD in children with ADHD. Using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (epidemiologic version) structured diagnostic interview,12 they evaluated 274 children (mean age 10.8±3.2) with ADHD; 37% had no comorbid mood disorder, 36% had ADHD with depression, and 11% had ADHD with BD. Researchers characterized 3 types of irritability in these patients:

- ODD-type irritability characterized by a low frustration tolerance that is seen in ODD

- Mad/cranky irritability found in depressive disorders

- Super-angry/grouchy/cranky irritability with frequent, prolonged, and largely unprovoked anger episodes and characteristics of mania.

ODD-type irritability was common among all ADHD patients, was the least impairing type of irritability, and did not increase the risk of a mood disorder. Mad/cranky irritability was common only in children with ADHD and a mood disorder (depression or BD), was more impairing than ODD-type irritability, and was most predictive of unipolar depression. Super-angry/grouchy/cranky irritability was common only among children with ADHD and BD (77%), was the most impairing, and was predictive of both unipolar depression and BD. The type of irritability and clustering of DSM-IV manic symptoms best differentiated ADHD subjects from those with ADHD and BD. Figure 2 illustrates symptoms that differentiated patients with ADHD from those with ADHD and comorbid BD.11

A review of pharmacotherapy for aggression in children found the largest effects for methylphenidate for aggression in ADHD (mean effect size=0.9, combined N=844).13 Our clinical experience has been that pediatric patients with ADHD or ODD with ADHD often have high levels of reactive aggression that presents as mood swings, and aggressively treating ADHD often results in improved mood and other ADHD symptoms.

Figure 2 Symptoms that differentiate BD from BD with comorbid ADHD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

Source: Reference 11

Anxiety disorders

The estimated prevalence of child and adolescent anxiety disorders is 10% to 20%14; in our sample the prevalence was 15%. These disorders include GAD, separation anxiety disorder, social phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Often, children with GAD worry excessively and become upset during transitions when things don’t proceed as they expect, with resultant angry outbursts and mood swings. Mood swings and difficulty sleeping are common in children with anxiety disorders or BD. Anxiety disorders often will be missed unless specific triggers of the mood swings or angry outbursts—as well as differentiating symptoms such as excessive fear, worry, and psychosomatic symptoms—are assessed.

In our clinical experience, simply asking a child if he or she is anxious is not sufficient to uncover an anxiety disorder. Although the CPRS-L:R will screen for anxiety disorders, we have found that the Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) developed by Birmaher et al15 is more specific. This tool can be used in patients age ≥8. The parent and child versions of the SCARED contain 41 items that measure 5 factors:

- general anxiety

- separation anxiety

- social phobia

- school phobia

- physical symptoms of anxiety.

The SCARED takes 5 minutes to fill out and is available in parent and child versions.

Secondary mood disorders

Many patients in our sample had a mood disorder secondary to the neurologic effects of alcohol on the developing brain. For more about maternal alcohol use, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, and mood swings, visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

What BD looks like in children

In our sample, 12% of patients referred for mood swings were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder (BDI), bipolar II disorder (BDII), or bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified (BD-NOS). In the United States, lifetime prevalence of BDI and BDII in adolescents age 13 to 17 is 2.9%.16 No large epidemiologic studies have looked at the lifetime prevalence of BD in children age <13.

How often a clinician sees BD in children and adolescents largely depends on the type of setting in which he or she practices. Although in the general population BD is relatively rare compared with other childhood psychiatric disorders, on child/adolescent inpatient units it is common to find that 30% to 40% of patients have BD.17

The best longitudinal study to date of the phenomenology, comorbidity, and outcome of BD in children and adolescents is the National Institute of Mental Health-funded Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study (COBY).18 In this ongoing, longitudinal study, 413 youths (age 7 to 17) with BDI (N=244), BDII (N=28), or BD-NOS (N=141) were rigorously diagnosed using state-of-the-art measures, including the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present version19 and re-evaluated every 9.4 months for 4 years. When organizing this study, investigators found that DSM-IV criteria for BD-NOS were too vague to be useful and developed their own criteria (Table 2).18

For BDI patients in the COBY study, the mean age of onset for bipolar symptoms was 9.0±4.1 years and the mean duration of illness was 4.4±3.1 years. Researchers reported that at the 4-year assessment approximately 70% of patients with BD recovered from their index episode, and 50% had at least 1 syndromal recurrence, particularly depressive episodes.20 Analyses of these patients’ weekly mood symptoms showed that they had syndromal or subsyndromal symptoms with numerous changes in symptoms and shifts of mood polarity 60% of the time, and psychosis 3% of the time. During this study, 20% of BDII patients progressed to BDI, and 25% of BD-NOS patients converted to BDI or BDII.

Further analysis of the COBY data revealed that onset of mood symptoms preceded onset of clear bipolar episodes by an average of 1.0±1.7 years. Depression was the most common initial and most frequent episode for adolescents; mood lability was seen more often in childhood-onset and adolescents with early-onset BD. Depressed children had more severe irritability than depressed adolescents, and older age was associated with more severe and typical mood symptomatology.21

The clinical picture of a child with BD that emerges from the COBY study is:

- a fairly young child with the onset of mood symptoms between age 5 to 12

- subsyndromal and less frequently clear syndromal episodes

- primarily mixed and depressed symptoms with rapid mood cycles during these episodes.22

It is clear that there is a spectrum of bipolar disorders in children and adolescents with varying degrees of symptom expression and children differ from adolescents and adults in their initial presentation of BD.

Table 2

COBY criteria for bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified

| Presence of clinically relevant bipolar symptoms that do not fulfill DSM-IV criteria for BDI or BDII |

| In addition, patients are required to have elevated mood plus 2 associated DSM-IV symptoms or irritable mood plus 3 DSM-IV associated symptoms, along with a change in level of functioning |

| Duration of a minimum of 4 hours within a 24-hour period |

| At least 4 cumulative lifetime days meeting the criteria |

| BDI: bipolar I disorder; BDII: bipolar II disorder; COBY: Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study |

| Source: Reference 18 |

Related Resources

- Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling RL, et al. Clinical manual for management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Miklowitz DJ, Cicchetti D, eds. Understanding bipolar disorder: a developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010.

Drug Brand Name

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta, others

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch receives grant/research support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health and is a consultant to AstraZeneca, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and the REACH Foundation.

Dr. Delgado and Ms. Monroe report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Table

FIND criteria of disorders found to cause mood swings

| Criteria | BDI | BP-NOS | ODD | GAD | ARND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of symptoms/week | 7 days (more days than not in an average week) | 2 to 3 days/week | Daily (chronic) irritability and mood swings precipitated by ‘not getting their way’ | Greatest during times of change/stress | Daily |

| Intensity of symptoms | Severe—parents often are afraid to take the child out in public because of mood symptoms | Moderate | Mild/moderate | Mild/moderate when stressed | Mild/moderate |

| Number of mood cycles/day | Daily cycles of euphoria and depression | 3 to 4 | 5 to 10 | 2 to 3 | 8 to 10 |

| Duration of symptoms/day | Euphoria: 30 to 60 minutes Depression: 30 minutes to 6 hours | 4 hours total/day of mood symptoms | Short; 5 to 10 minutes | Short; 5 to 10 minutes | Short; 5 to 10 minutes |

| ARND: alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; BDI: bipolar I disorder; BD-NOS: bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder | |||||

| Source: Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling RL, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008 | |||||

Even small amounts of alcohol use by a pregnant woman can impact her child’s development. In a controlled study examining drinking behavior of 12,678 pregnant women and the effect this had on their children, Sayel et ala found that <1 drink per week during the first trimester was clinically significant for mental health problems in girls, measured at age 4 and 8, when using parent or teacher report.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder describes the range of effects that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. These disorders include fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD).

FAS. Individuals with FAS have a distinct pattern of facial abnormalities, growth deficiency, and evidence of CNS dysfunction. Characteristic facial abnormalities may include a smooth philtrum, thin upper lip, upturned nose, flat nasal bridge and midface, epicanthal folds, small palpebral fissures, and small head circumference. Growth deficiency begins in-utero and continues throughout childhood and into adulthood. CNS abnormalities can include impaired brain growth or abnormal structure, manifested differently depending on age.

ARND. Many individuals affected by alcohol exposure before birth do not have the characteristic facial abnormalities and growth retardation identified with full FAS, yet have significant brain and behavioral impairments. Individuals with ARND have either the facial anomalies, growth retardation, and other physical abnormalities, or a complex pattern of behavioral or cognitive abnormalities inconsistent with developmental level and unexplained by genetic background or environmental conditions (ie, poor impulse control, language deficits, problems with abstraction, mathematical and social perception deficits, learning problems, and impairment in attention, memory, or judgment).b

ARBD. Persons with ARBD have malformations of the skeletal and major organ systems, such as cardiac or renal abnormalities.

Comorbid psychiatric conditions in children with prenatal alcohol exposure are 5 to 16 times more prevalent than in the general population; these children are 38% more likely to have an anger disorder.c O’Connor and Paleyd found that “…mood disorder symptoms were significantly higher for children with parental alcohol exposure compared to children without exposure.” Children with ARND are treated symptomatically depending upon which deficits and behaviors they exhibit.e

References

a. Sayal K, Heron J, Golding J, et al. Binge pattern of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and childhood mental health outcomes: longitudinal population-based study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e289-296.

b. Warren KR, Foudin LL. Alcohol-related birth defects—the past, present, and future. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(3):153-158.

c. Burd L, Klug MG, Martsolf JT, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome: neuropsychiatric phenomics. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25(6):697-705.

d. O’Connor MJ, Paley B. Psychiatric conditions associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):225-234.

e. Paley B, O’Connor MJ. Intervention for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: treatment approaches and case management. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):258-267.

M, age 13, is referred by her pediatrician with the chief complaint of “severe mood swings, rule out bipolar disorder (BD).” In the past she was treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with stimulants with mixed results. M’s parents are concerned about her “flipping out” whenever she is asked to do something she does not want to do. Her mother has a history of depression and anxiety; her father had a “drinking problem.” There is no history of BD in her first- or second-degree relatives. Are M’s rapid mood swings a sign of BD or another disorder?

The differential diagnosis of “mood swings” is important because they are a common presenting symptom of many children and adolescents with mood and behavioral disorders. Mood swings often occur in children and adolescents with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), developmental disorders, depressive disorders, BD, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorders. Mood swings are analogous to a fever in pediatrics—they indicate something potentially is wrong with the patient, but are not diagnostic as an isolated symptom.

Mood swings in children are common, nonspecific symptoms that more often are a sign of anxiety or behavioral disorders than BD. This article discusses the differential diagnosis of mood swings in children and adolescents and how to best screen and diagnose these patients.

What are ‘mood swings’?

Mood swings is a popular term that is nonspecific and not part of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for BD. The complaint of “mood swings” may reflect severe mood lability of pediatric patients with BD. This mood lability is best described by the Kiddie-Mania Rating Scale (K-MRS) developed by Axelson and colleagues as “rapid mood variation with several mood states within a brief period of time which appears internally driven without regard to the circumstance.”1 On K-MRS mood lability items, children with mania typically score:

- Moderate—many mood changes throughout the day, can vary from elevated mood to anger to sadness within a few hours; changes in mood are clearly out of proportion to circumstances and cause impairment in functioning

- Severe—rapid mood swings nearly all of the time, with mood intensity greatly out of proportion to circumstances

- Extreme—constant, explosive variability in mood, several mood changes occurring within minutes, difficult to identify a particular mood, changes in mood radically out of proportion to circumstances.

Patients with BD typically exhibit what is best described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from 1 extreme to another.2 An example of this would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours and then later in the day becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle. BD patients also will exhibit other symptoms of mania during these mood cycling periods.

Rapid cycling is a DSM-IV course specifier that indicates ≥4 mood episodes per year in patients with BD with a typical course of mania or hypomania followed by depression, or vice versa.3 The episodes must be demarcated by full or partial remission that lasts ≥2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity. In the past, children with frequent mood swings were described incorrectly as “rapid cycling,” but this term has been dropped because it engenders confusion between adult and pediatric BD phenomenology.2

A more precise method of describing mood symptoms in a child or adolescent is to use the FIND criteria, which include:4

- Frequency of symptoms per week

- Intensity of mood symptoms

- Number of mood cycles per day

- Duration of symptoms per day.

Visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com to view a table that outlines what to look for when using the FIND criteria to evaluate common pediatric psychiatric disorders that include mood swings. Table 1

describes clinical characteristics and tools and resources used to differentiate these and other disorders.4

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of psychiatric disorders that often feature mood swings

| Disorder | Clinical description | Useful tools/resources |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Chronic symptoms of hyperactivity, distractibility, impulsivity, poor attentional skills, disorganization | Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) |

| ODD | Chronic symptoms of oppositionality, negativity; short, frequent mood swings in response to being asked to do something they do not want to do | CPRS-R:L |

| Anxiety disorders | Excessive ‘worry,’ difficulty with transitions, increased mood swings during stressful periods, psychosomatic symptoms | Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders |

| ARND | History of exposure to alcohol in-utero; mild dysmorphia, attentional, mood, and executive functioning problems | National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome |

| Bipolar disorder | In children: clustering together of episodes or ‘mini-episodes’ (several days) of increased energy, decreased need for sleep, increased mood cycling, pressured speech, etc. In adolescents: depressive episodes with episodes of hypomania or mania | Mood Disorders Questionnaire Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Mania Rating Scale |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ARND: alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder | ||

| Source: Reference 4 | ||

Mood swings: A chart review

We recently completed a retrospective chart review of 100 patients consecutively referred to our pediatric mood disorders clinic for evaluation of “mood swings, rule out BD.” These patients were self-referred, referred by a psychiatrist for a second opinion, or referred by their primary care physician. The mean age of these patients was 8±2.8 years and 68% were male.

Two experienced clinicians (RAK and EM) interviewed each patient and their caregivers and reviewed results of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L)5 and other outside information.

Figure 1 illustrates these patients’ diagnoses. Diagnoses for each of these disorders were made using DSM-IV-TR criteria.3

The most common diagnoses among patients with the chief complaint of mood swings were ADHD (39%); ODD with ADHD (15%); an anxiety disorder, usually generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (15%); BD (12%); and a secondary mood disorder, usually fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (10%). We were surprised at how often ADHD, ODD, and anxiety disorders were found to be responsible for these patients’ mood swings and how frequently the referring clinician did not recognize these disorders. In the following sections, we discuss each of these disorders and how they differ from BD.

Figure 1 Underlying diagnoses of 100 children/adolescents referred for ‘mood swings’

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder; PDD: pervasive developmental disorder

ADHD and ODD

In our sample, patients with undiagnosed ADHD made up the largest group of those with frequent mood swings. ADHD inattentive type was missed frequently in adolescent girls who still had behavioral aspects of ADHD, including impulsivity and aggression.6

The CPRS-R:L is useful for screening and diagnosing children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD. It contains 80 items, can be used in males and females and patients age 3 to 17, and has validated norms by age and sex.5 It takes parents approximately 10 minutes to fill out this questionnaire and the results can be scored by hand. The CPRS-R:L includes the following scales: oppositional; cognitive problems/inattention; hyperactivity; anxious-shy; perfectionism; social problems; psychosomatic; Connors’ global index; DSM-IV symptom subscales; and an ADHD index. Patients with mood swings and ADHD combined typically score >2 standard deviations above their age/sex mean on the CPRS-R:L hyperactivity scale, Connors’ Global Index, and ADHD index.5

A common childhood disorder, ODD has multiple etiologies.7 The first DSM-IV criteria for ODD is “often loses temper”3—essentially mood swings that often are expressed behaviorally as anger and at times as aggressive outbursts.

Dodge and Cole8 categorized aggression as reactive (impulsivity with a high affective valence) or proactive (characterized by low arousal and premeditation, ie, predatory conduct disorder). Reactive aggression typically is an angry defensive response to frustration, threat, or provocation, whereas proactive aggression is deliberate, coercive behavior often used to obtain a goal.9 Reactive aggression is common among children with ADHD and ODD and typically begins as a mood swing that escalates into reactive aggressive behavior. In a study of 268 consecutively referred children and adolescents with ADHD and 100 community controls, Connor et al10 found significantly more reactive than proactive forms of aggression in ADHD patients.

It can be difficult to differentiate the moods swings and symptoms of ODD from those of pediatric BD. Mick et al11 found that severe irritability may be a diagnostic indicator of BD in children with ADHD. Using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (epidemiologic version) structured diagnostic interview,12 they evaluated 274 children (mean age 10.8±3.2) with ADHD; 37% had no comorbid mood disorder, 36% had ADHD with depression, and 11% had ADHD with BD. Researchers characterized 3 types of irritability in these patients:

- ODD-type irritability characterized by a low frustration tolerance that is seen in ODD

- Mad/cranky irritability found in depressive disorders

- Super-angry/grouchy/cranky irritability with frequent, prolonged, and largely unprovoked anger episodes and characteristics of mania.