User login

Transient Eruption of Verrucous Keratoses During Encorafenib Therapy: Adverse Event or Paraneoplastic Phenomenon?

To the Editor:

Mutations of the BRAF protein kinase gene are implicated in a variety of malignancies.1 BRAF mutations in malignancies cause the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to become constitutively active, which results in unchecked cellular proliferation,2,3 making the BRAF mutation an attractive target for inhibition with pharmacologic agents to potentially halt cancer growth.4 Vemurafenib—the first selective BRAF inhibitor used in clinical practice—initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2011. The approval of dabrafenib followed in 2013 and most recently encorafenib in 2018.5

Although targeted treatment of BRAF-mutated malignancies with BRAF inhibitors has become common, it often is associated with cutaneous adverse events (AEs), such as rash, pruritus, photosensitivity, actinic keratosis, and verrucous keratosis. Some reports demonstrate these events in up to 95% of patients undergoing BRAF inhibitor treatment.6 In several cases the eruption of verrucous keratoses is among the most common cutaneous AEs seen among patients receiving BRAF inhibitor treatment.5-7

In general, lesions can appear days to months after therapy is initiated and may resolve after switching to dual therapy with a MEK inhibitor or with complete cessation of BRAF inhibitor therapy.5,7,8 One case of spontaneous resolution of vemurafenib-associated panniculitis during ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy has been reported9; however, spontaneous resolution of cutaneous AEs is uncommon. Herein, we describe verrucous keratoses in a patient undergoing treatment with encorafenib that resolved spontaneously despite ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy.

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with pain in the right lower quadrant. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large ovarian mass. Subsequent bloodwork revealed elevated carcinoembryonic antigen levels. The patient underwent a hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse side-to-side anastomosis, right pelvic lymph node reduction, and complete cytoreduction. Histopathology revealed an adenocarcinoma of the cecum with tumor invasion into the visceral peritoneum and metastases to the left ovary, fallopian tube, and omentum. A BRAF V600E mutation was detected.

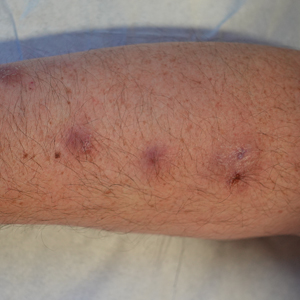

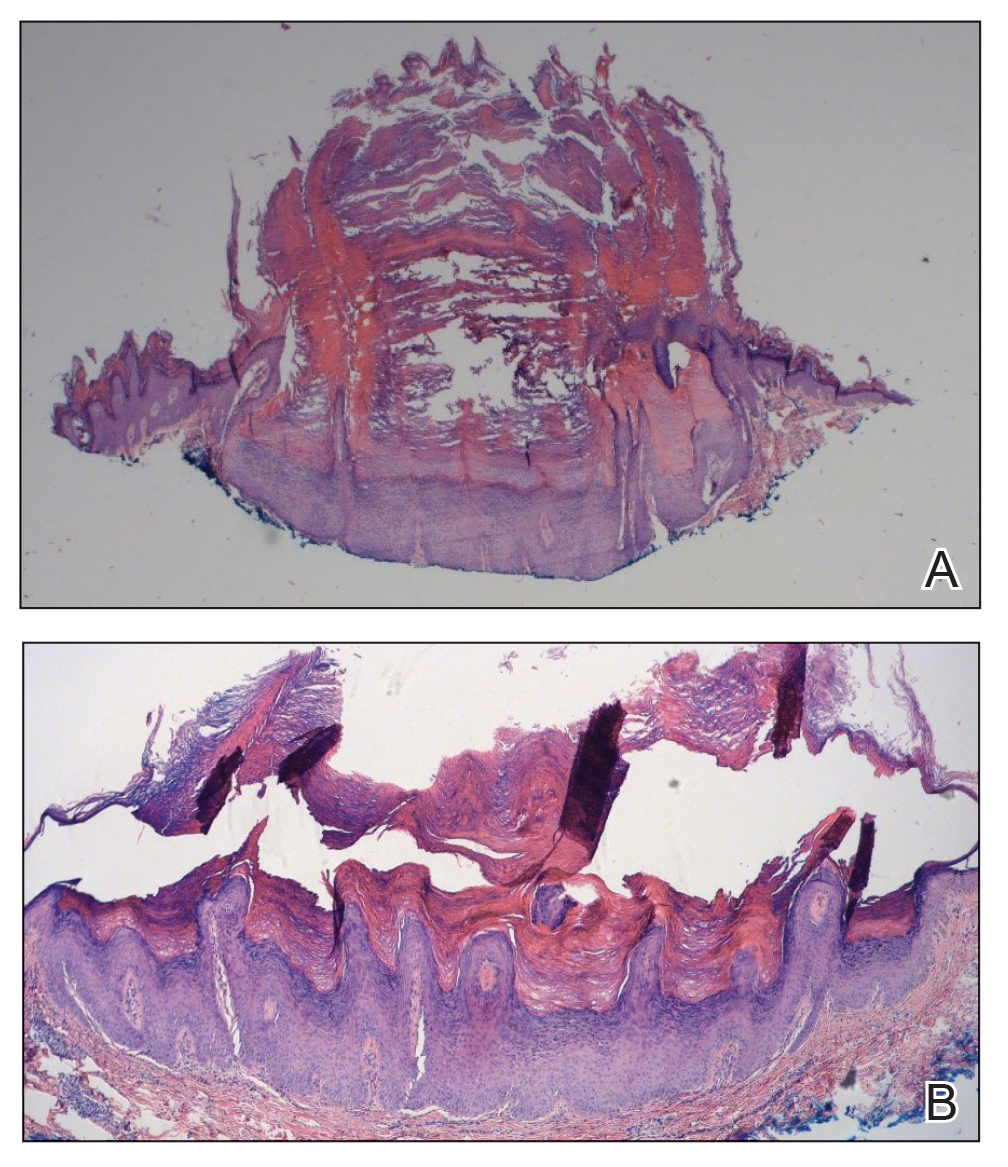

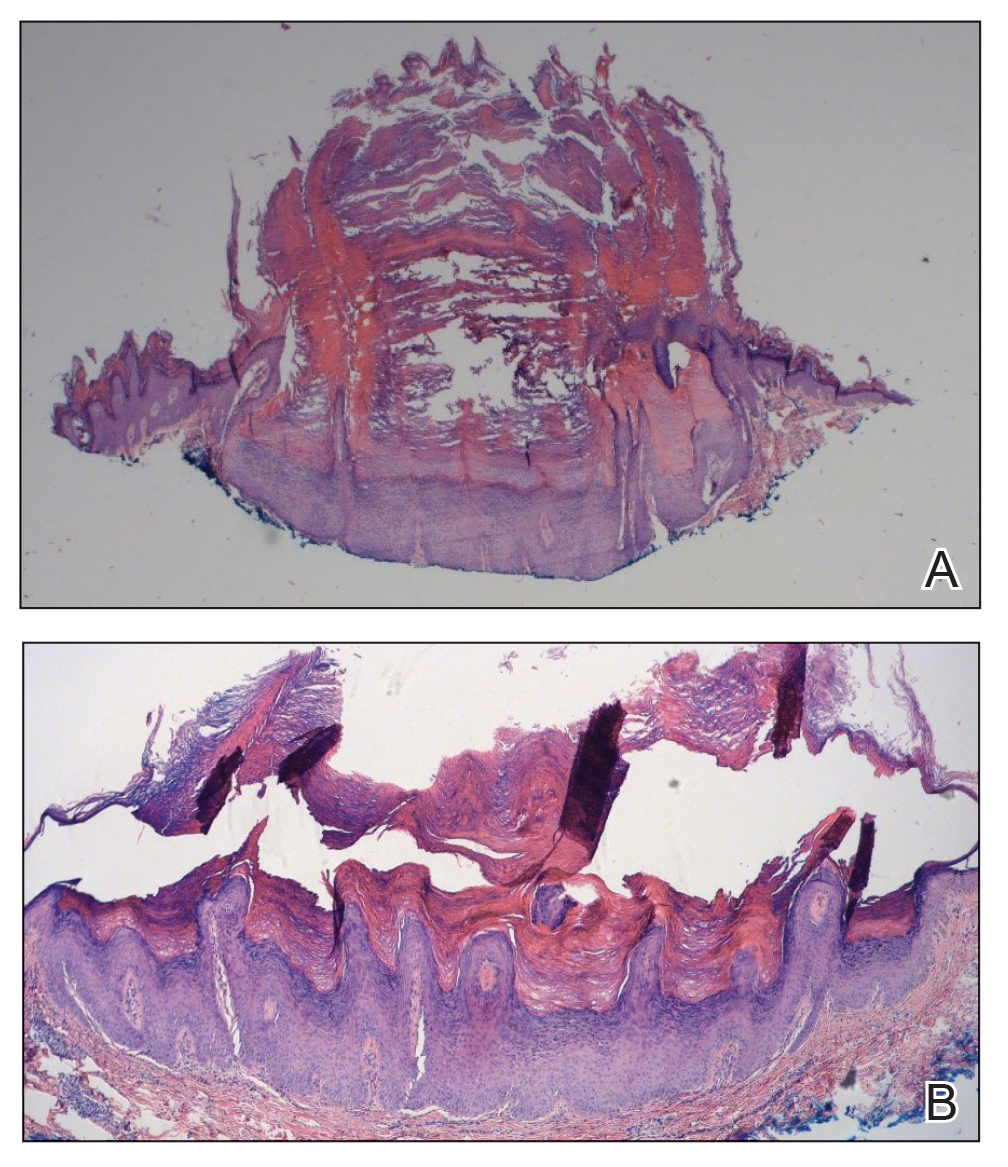

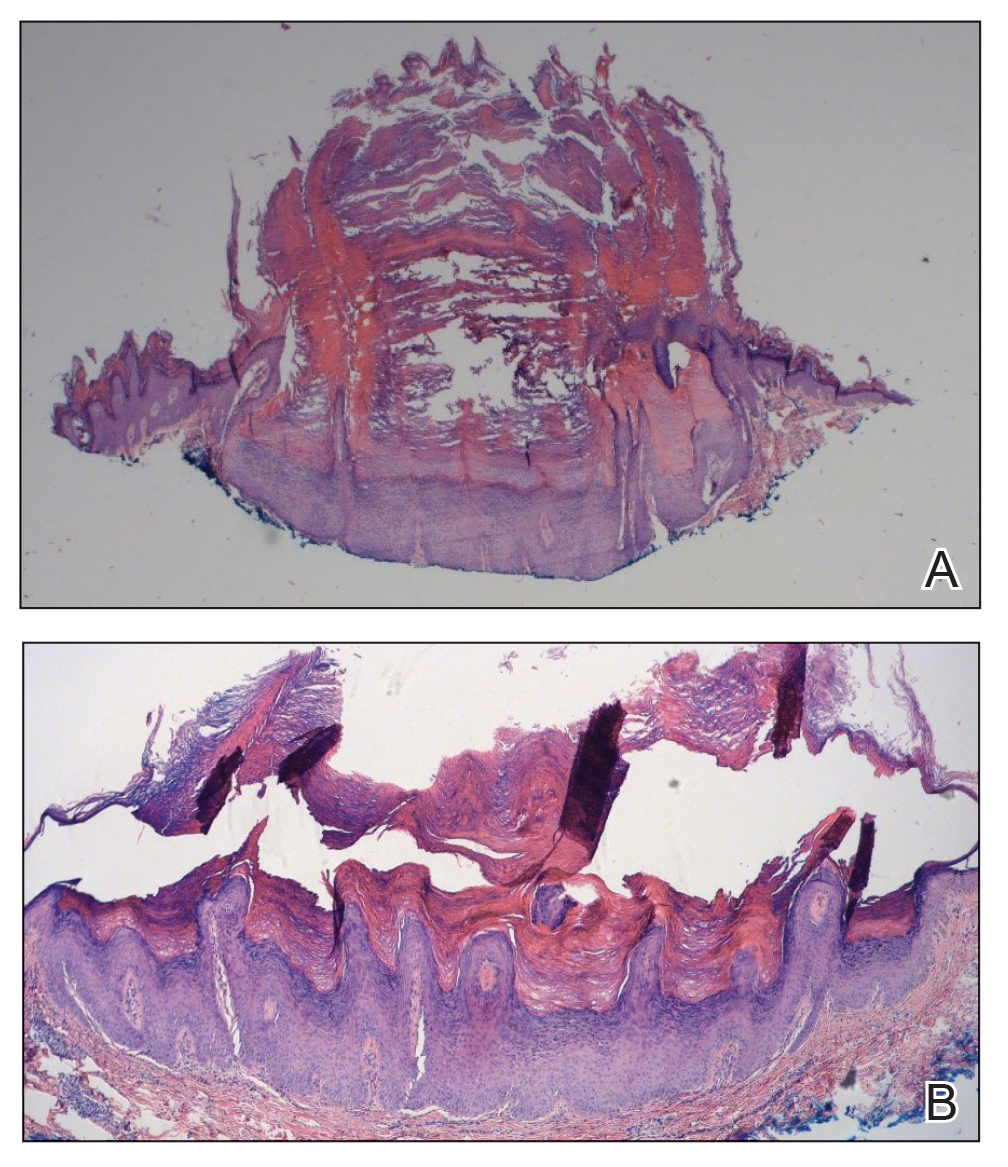

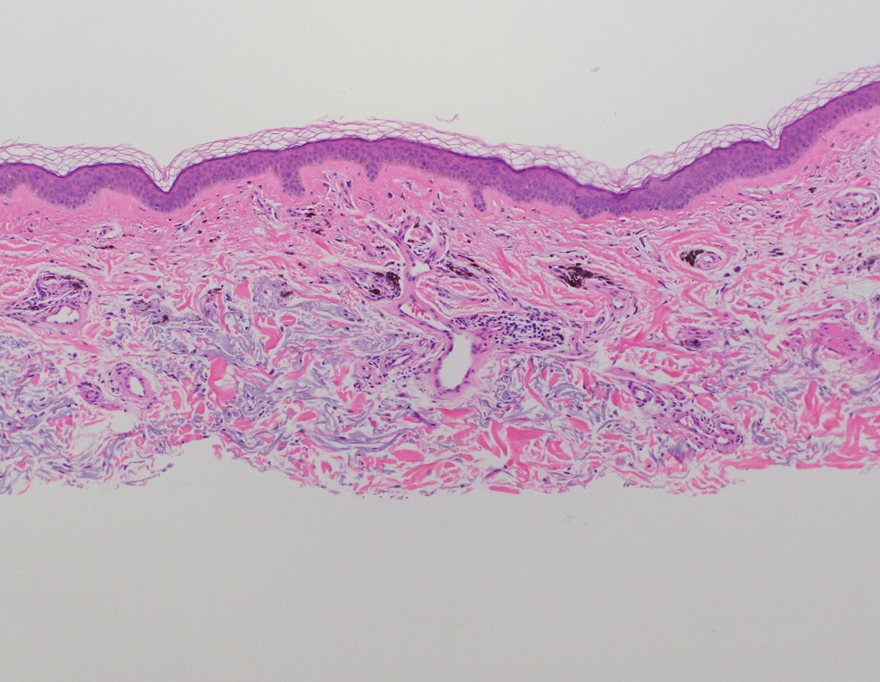

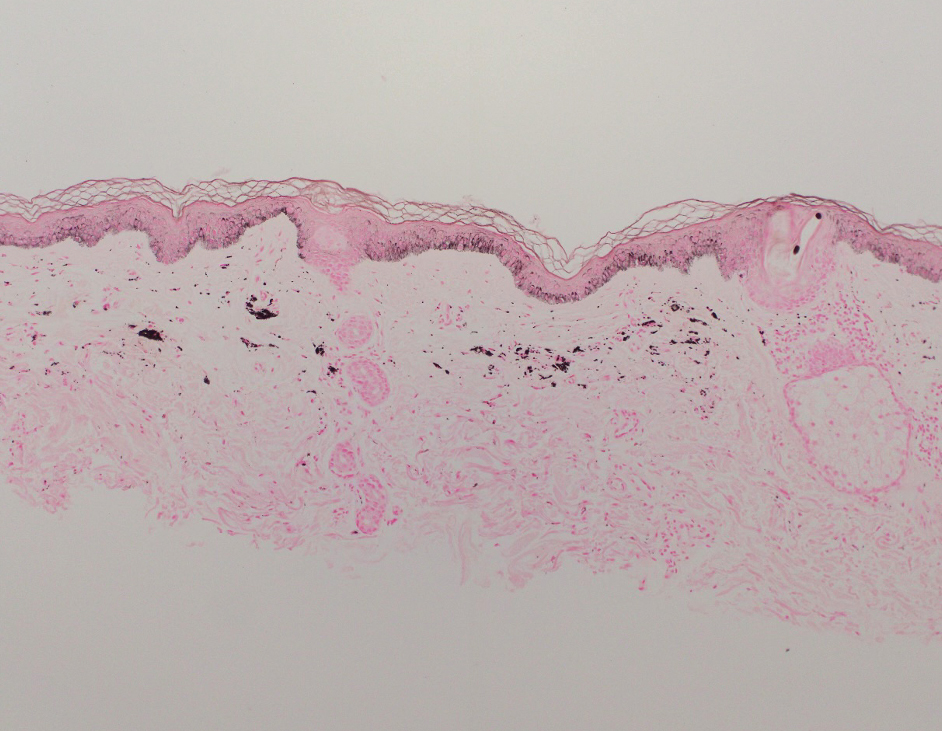

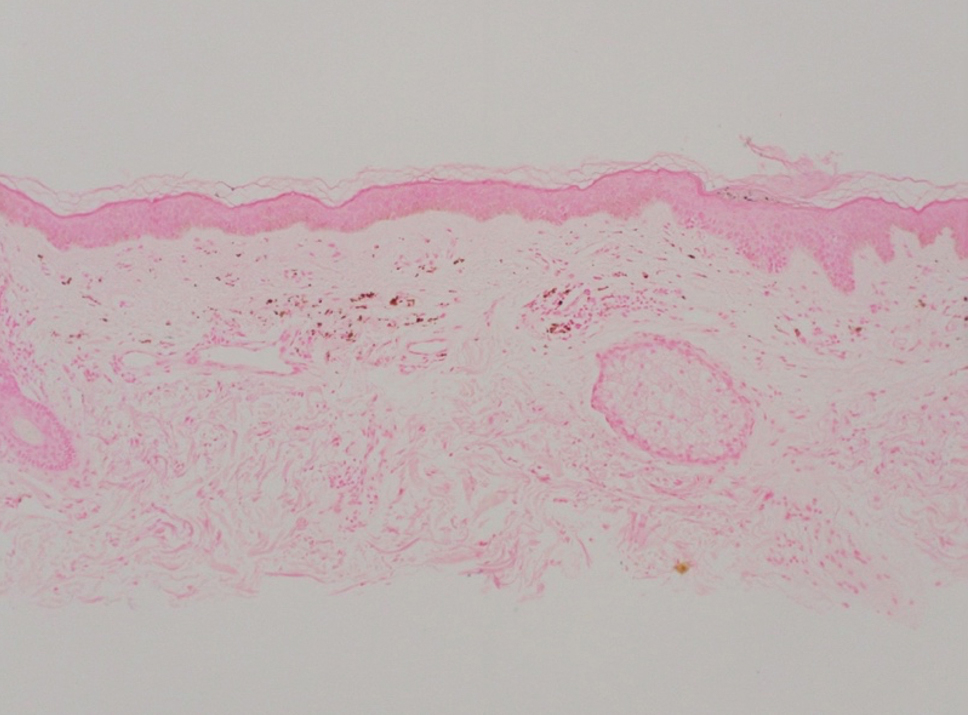

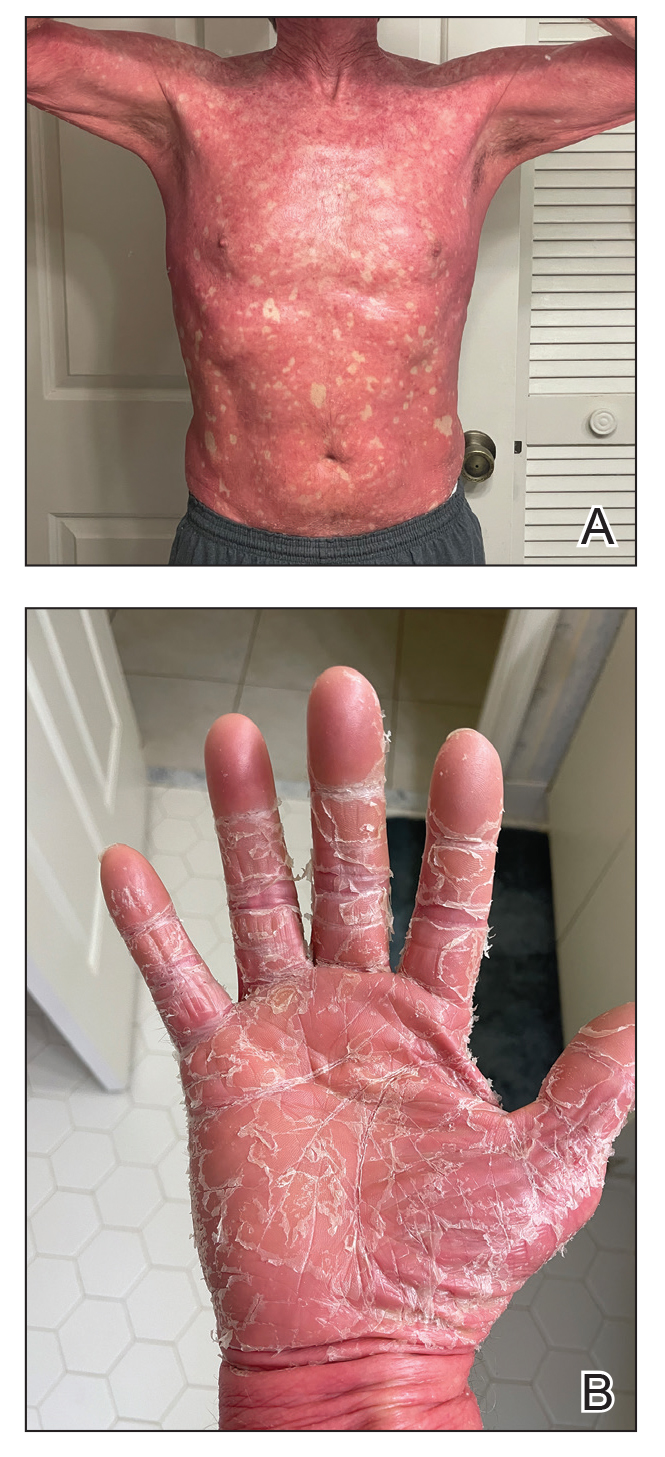

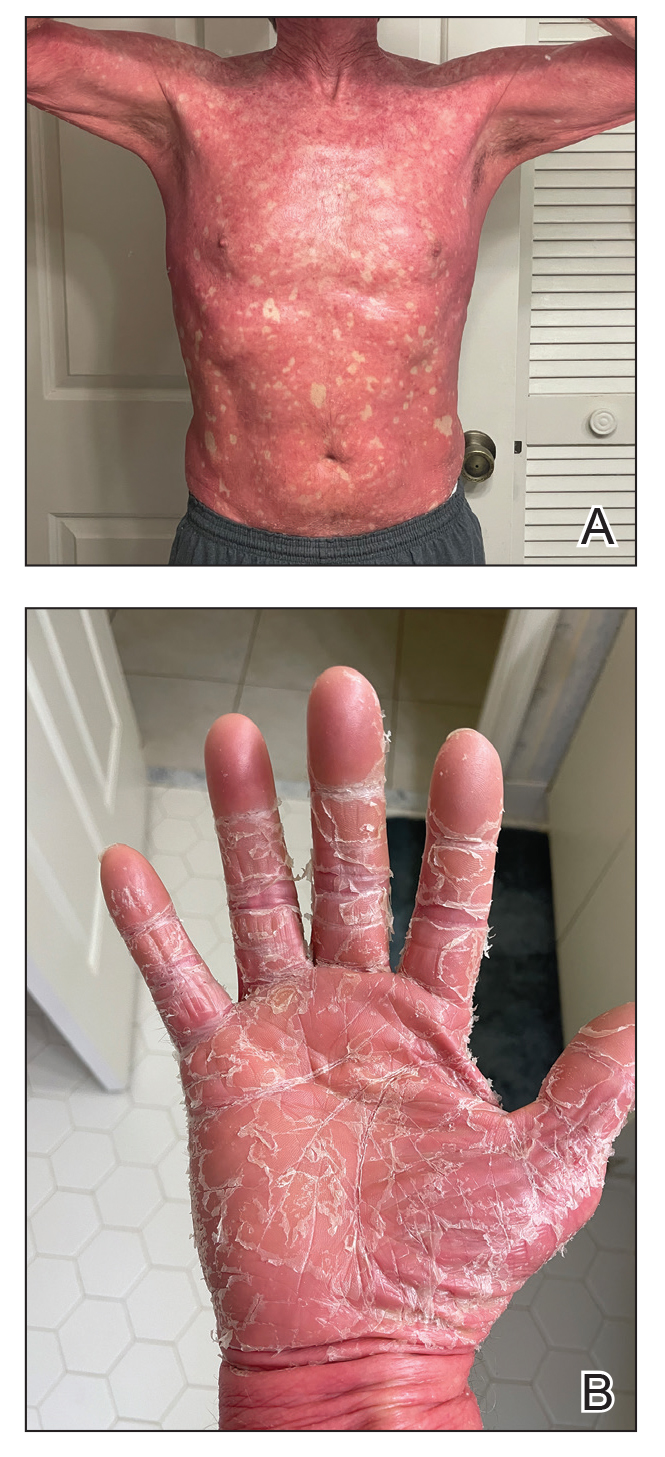

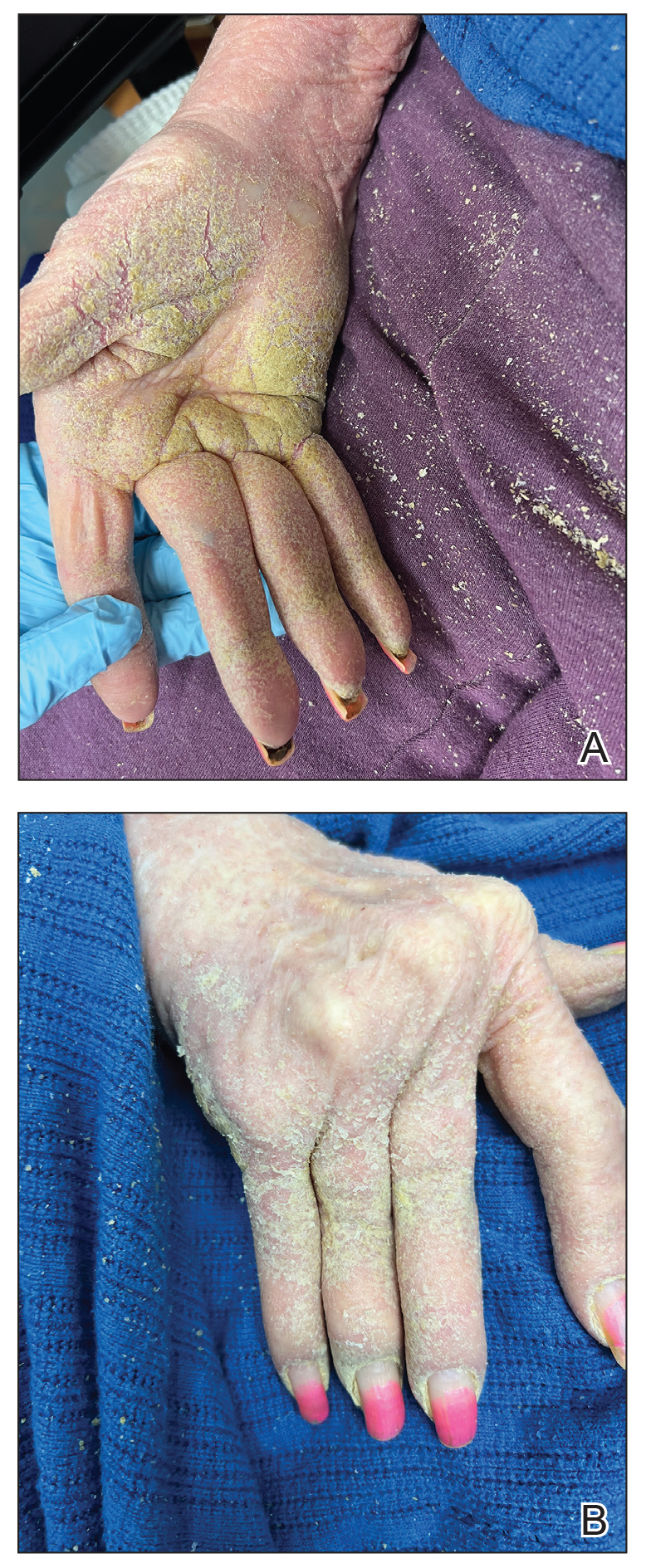

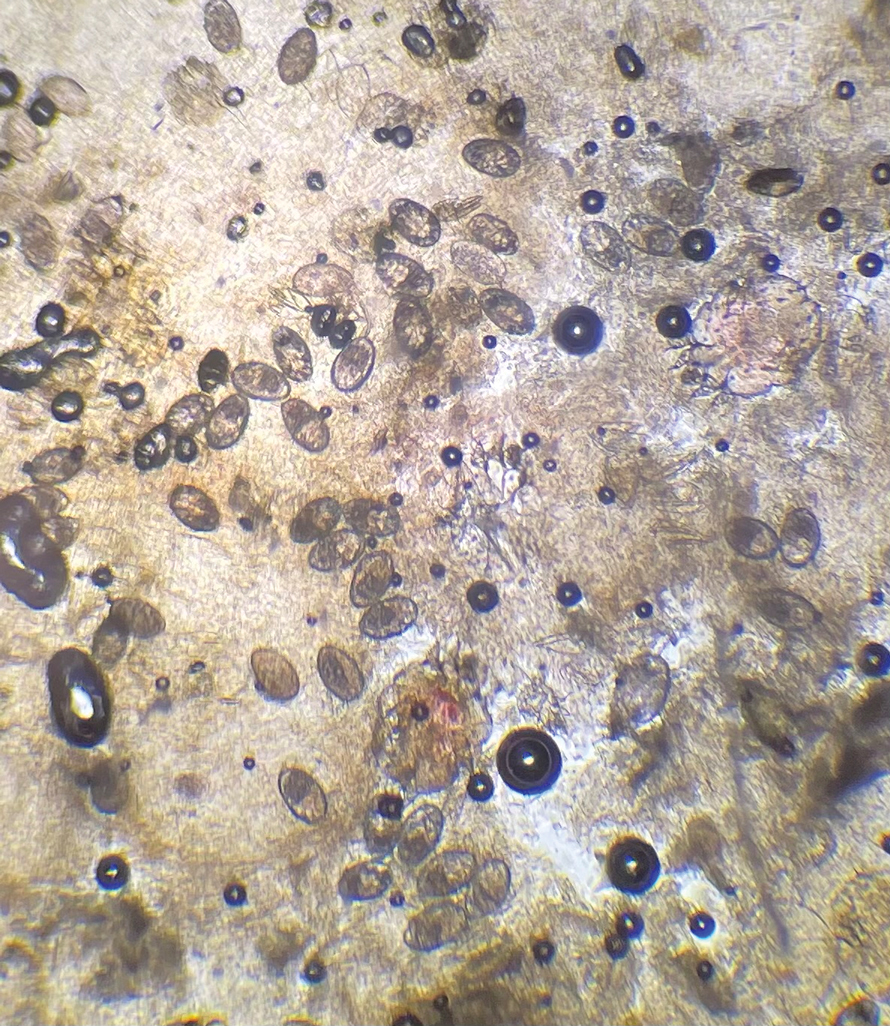

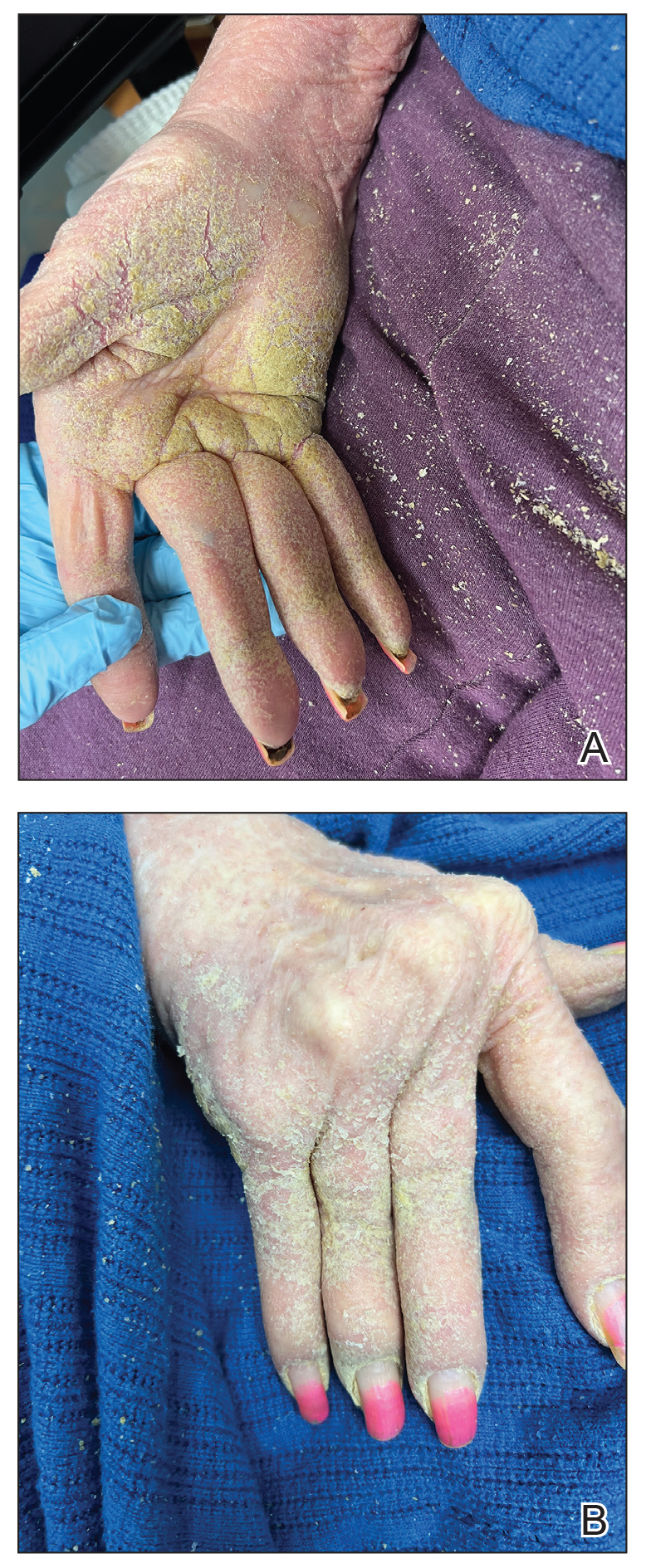

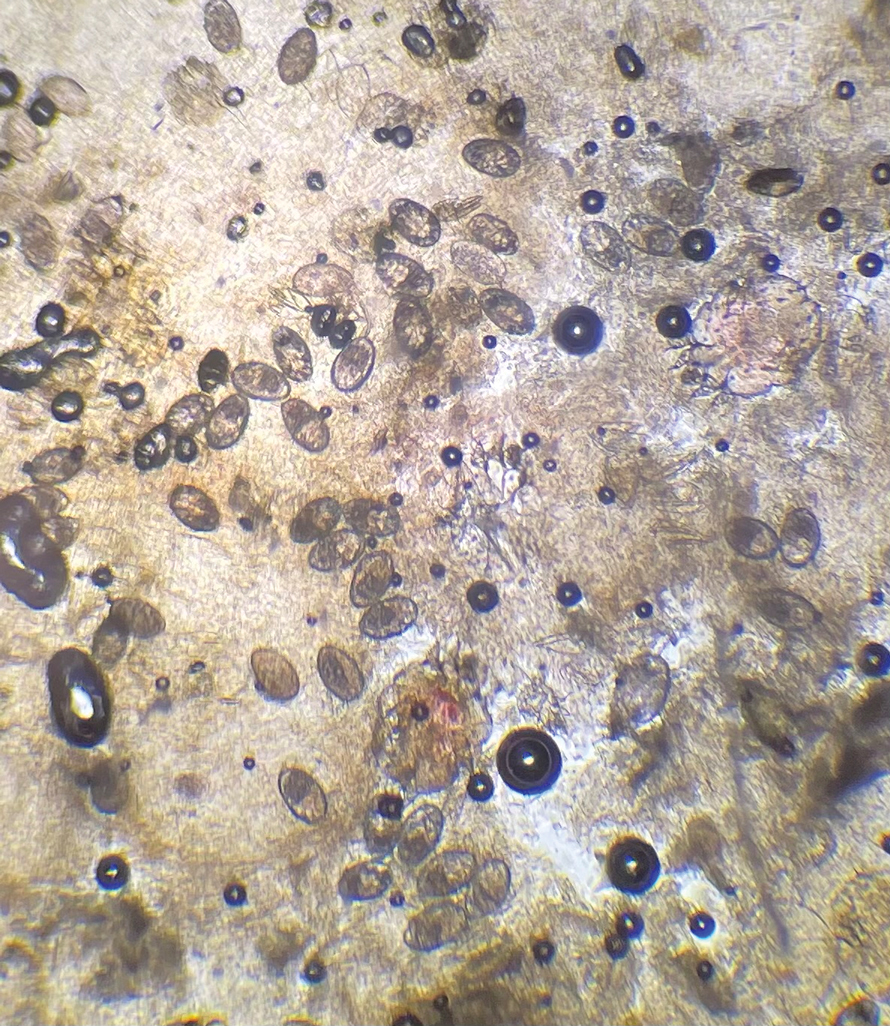

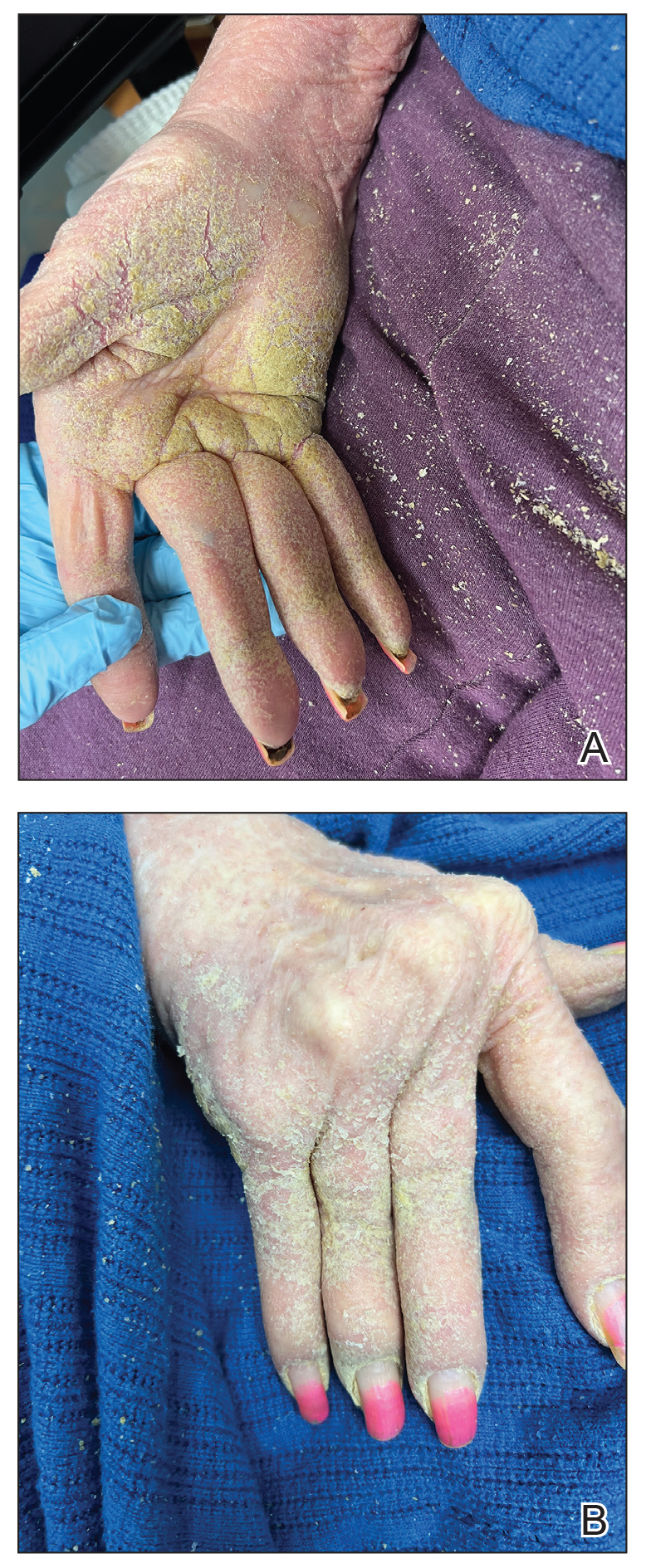

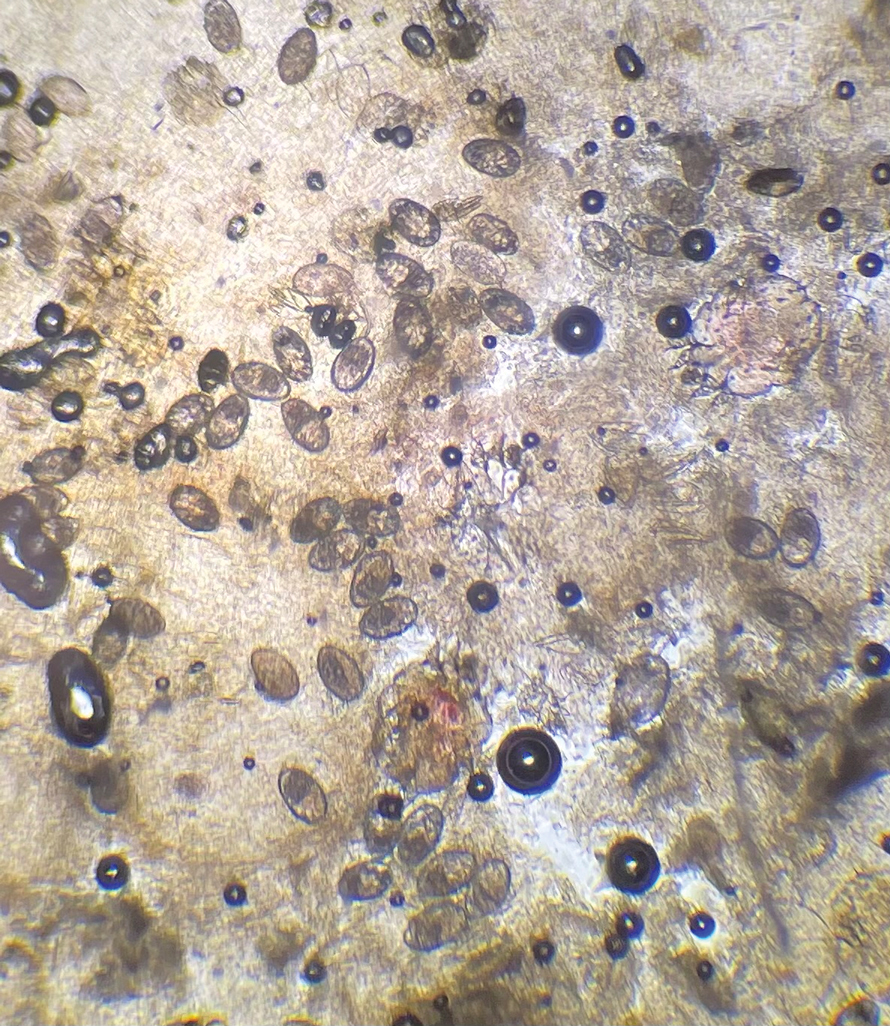

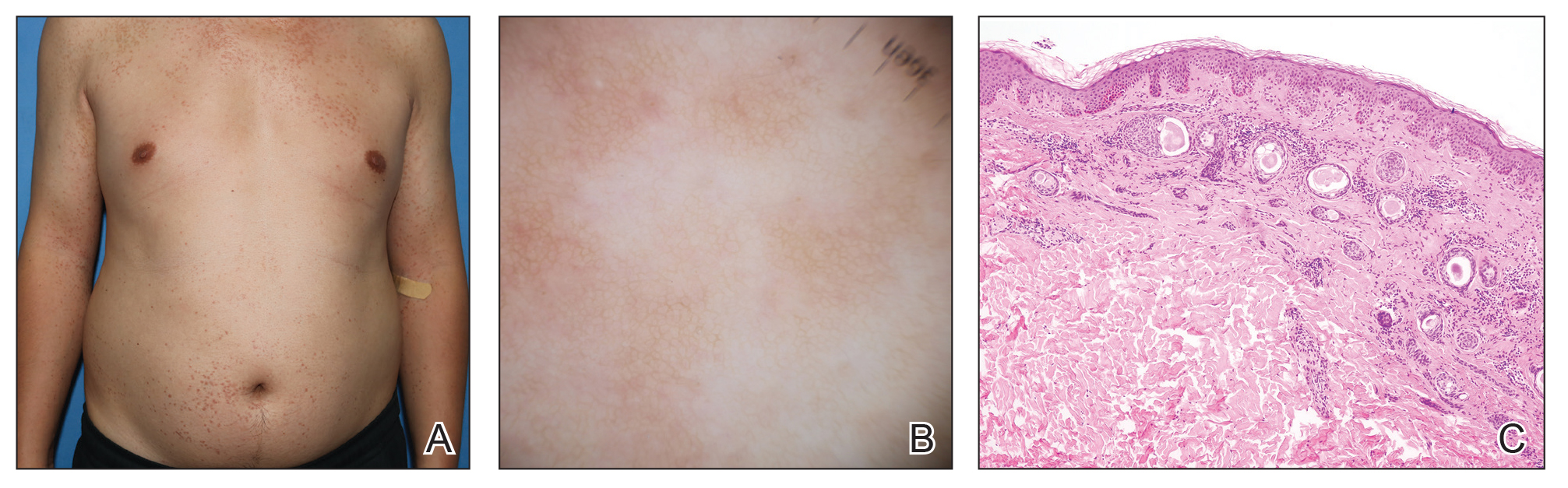

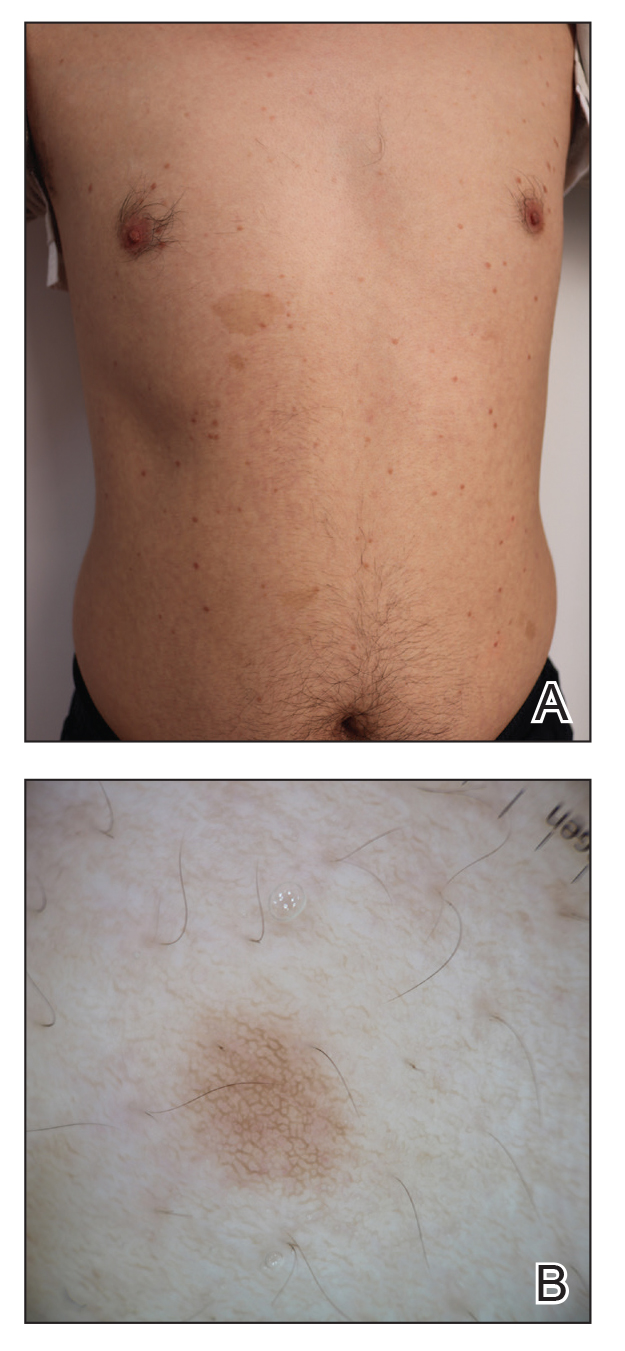

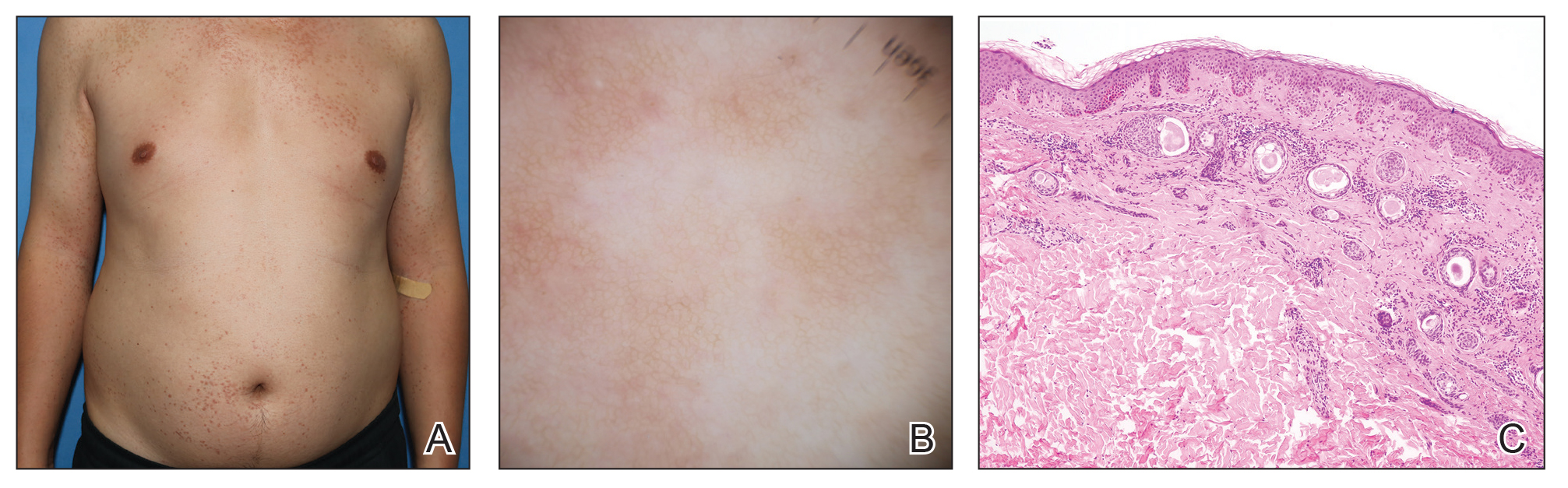

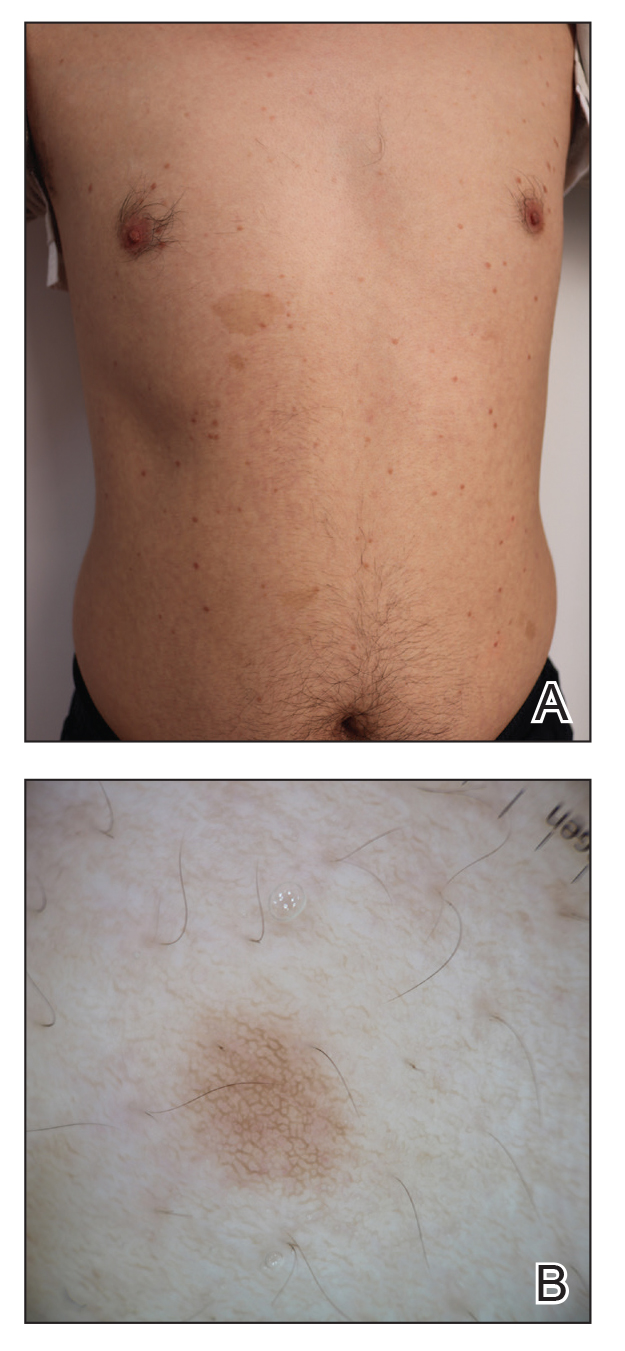

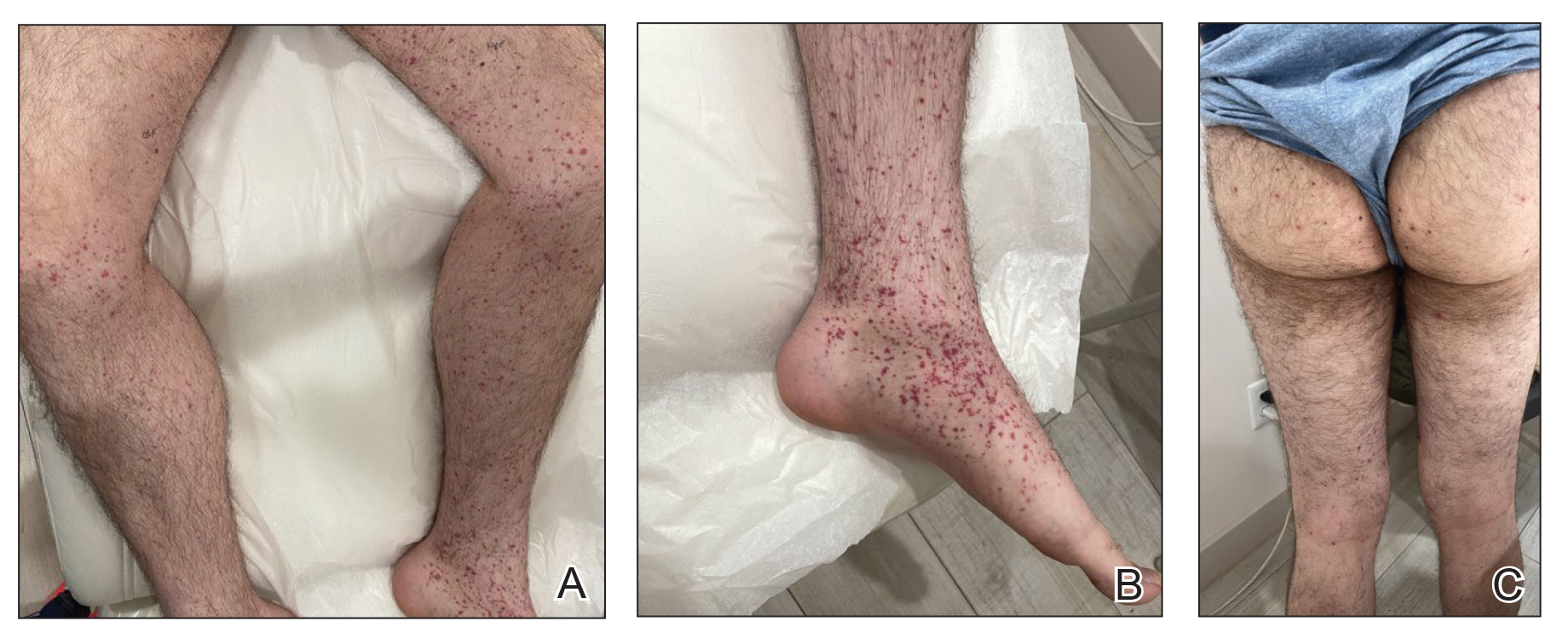

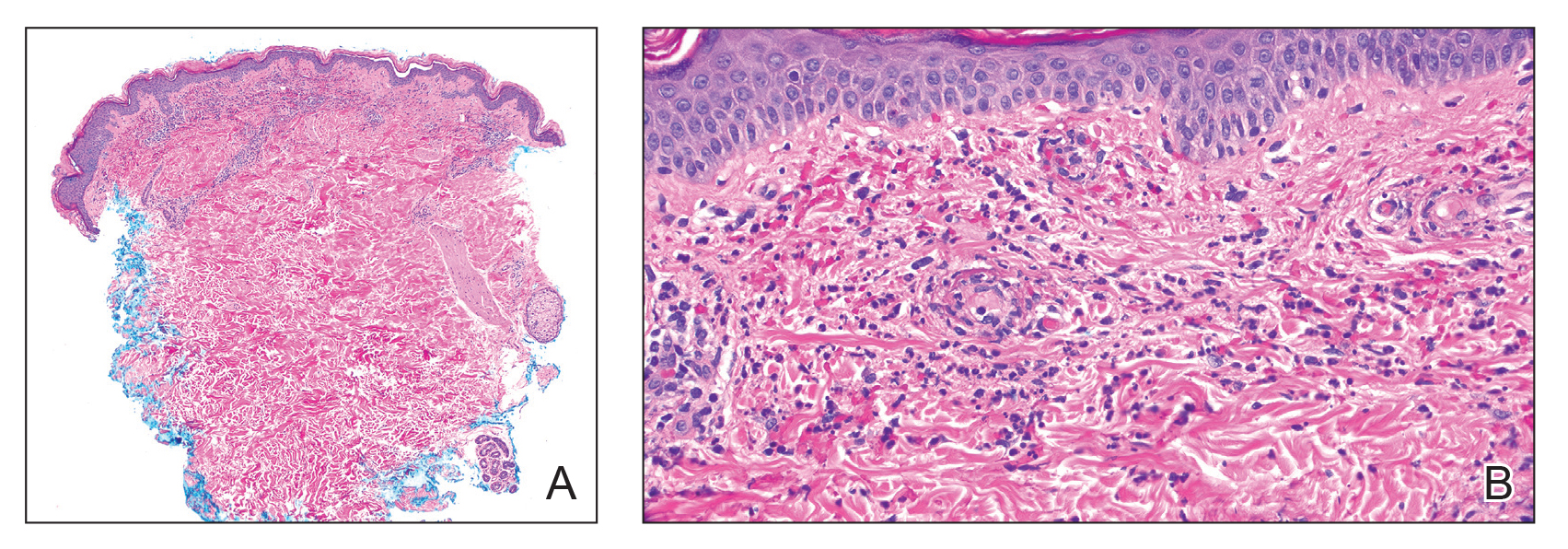

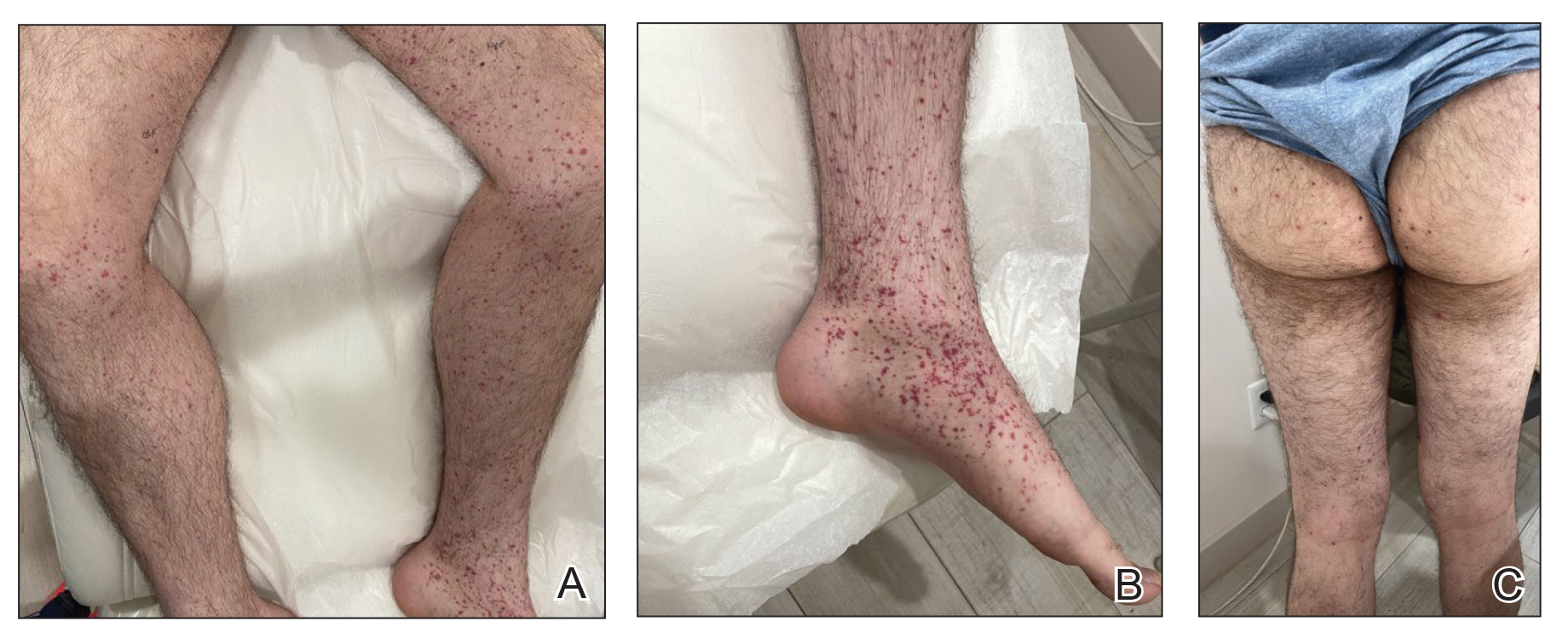

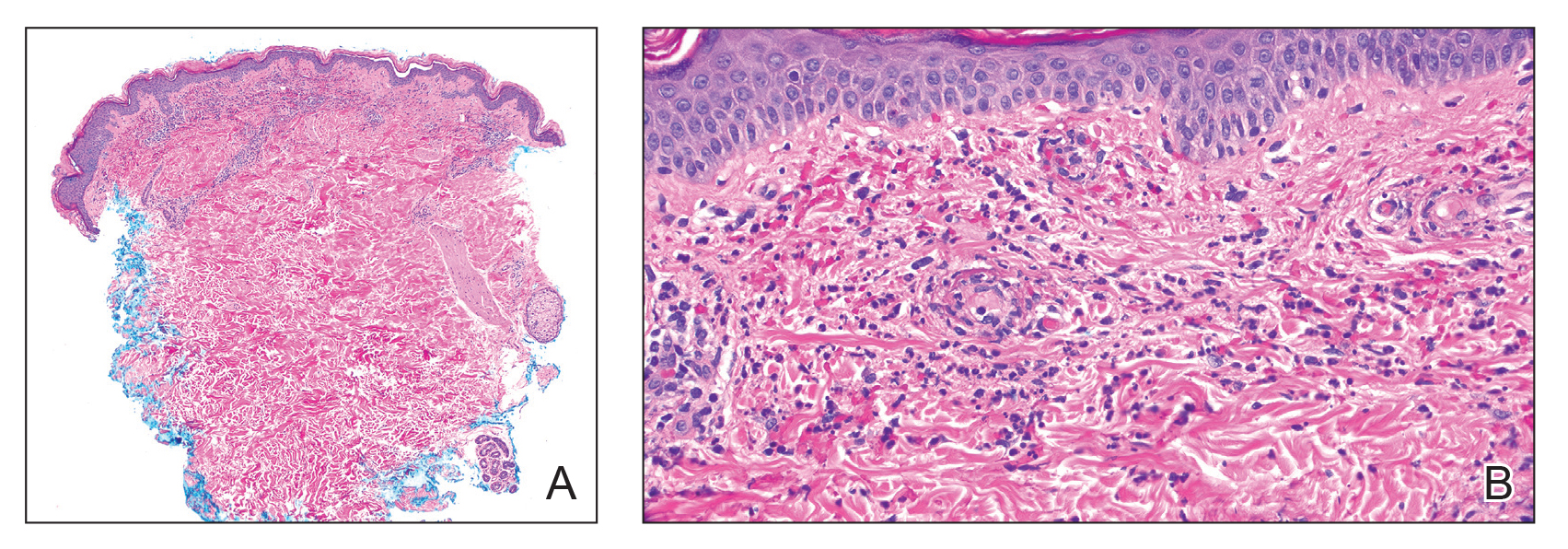

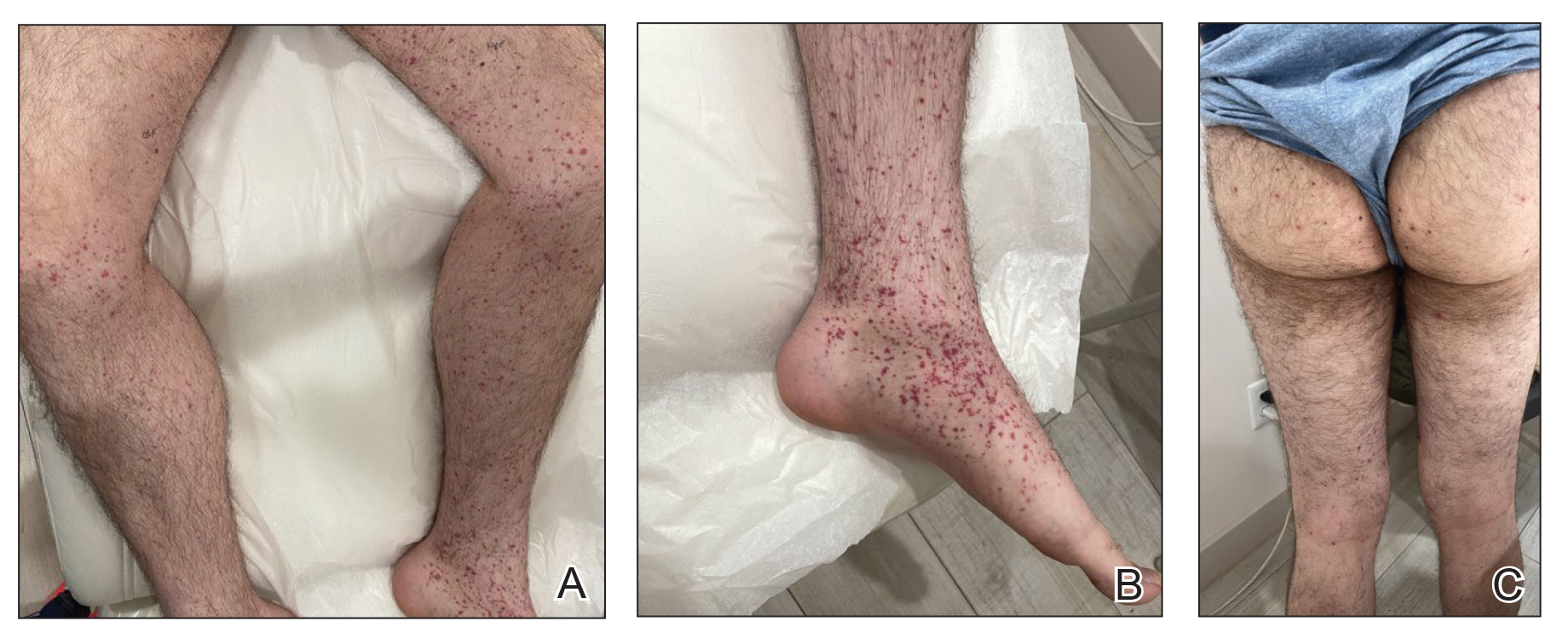

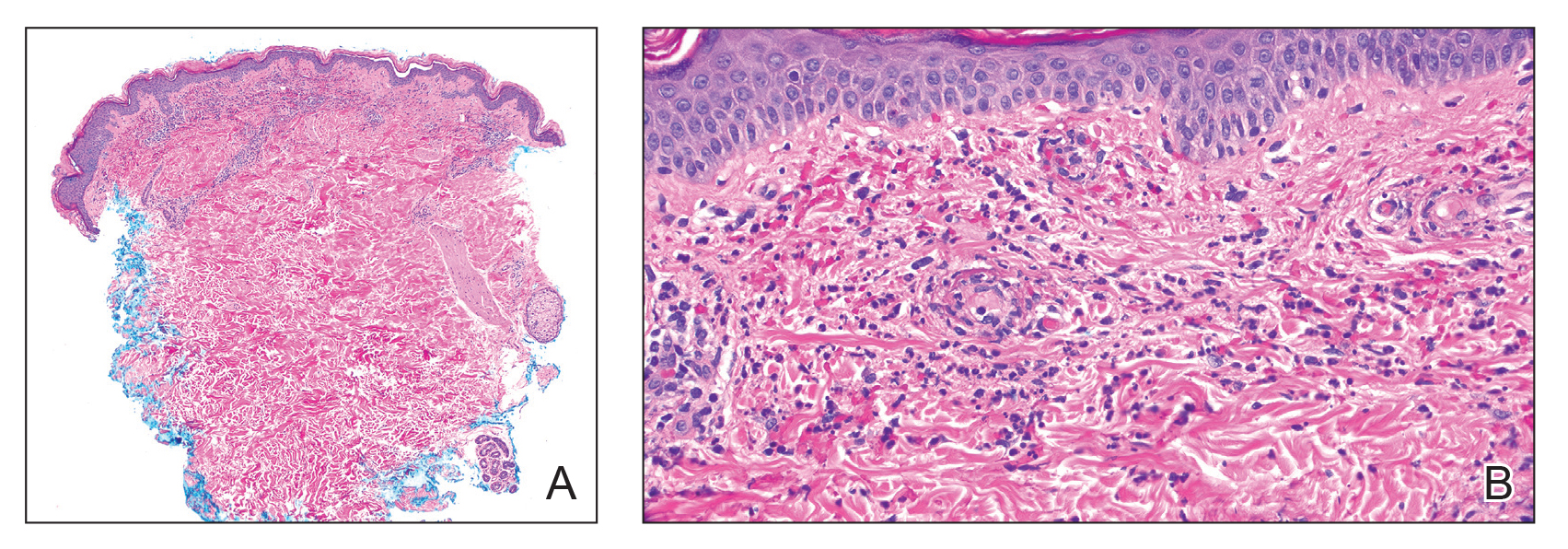

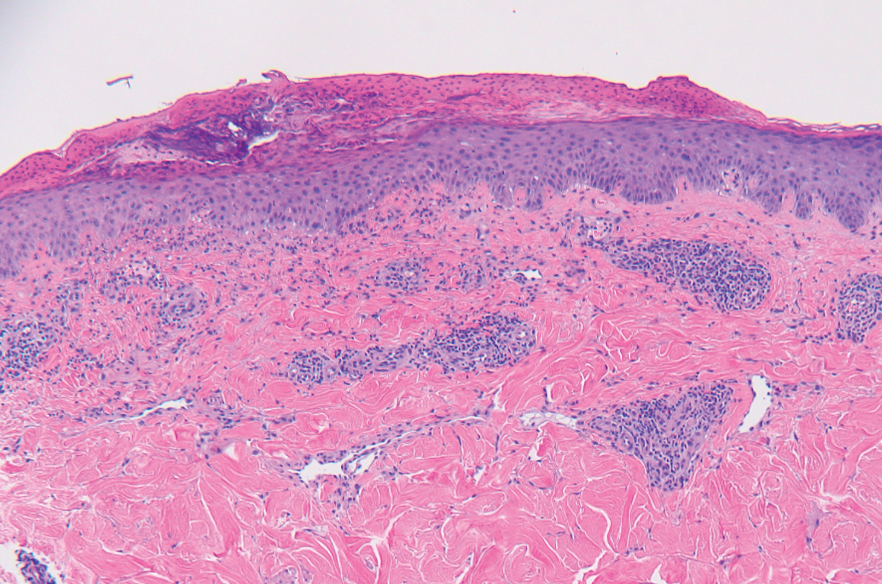

Two months after the initial presentation, the patient started her first cycle of chemotherapy with a combination of folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. She completed 11 cycles of this regimen, then was switched to capecitabine and oxaliplatin for an additional 2 cycles due to insurance concerns. At the end of treatment, there was no evidence of disease on CT, thus the patient was followed with observation. However, she presented 10 months later to the emergency department with abdominal pain, and CT revealed new lesions in the liver that were concerning for potential metastases. She started oral encorafenib 300 mg/d and intravenous cetuximab 500 mg weekly; after 1 week, encorafenib was reduced to 150 mg/d due to nausea and loss of appetite. Within 2 weeks of starting treatment, the patient reported the relatively abrupt appearance of more than 50 small papules across the shoulders and back (Figure 1A). She was referred to dermatology, and shave biopsies of 2 lesions—one from the left anterior thigh, the other from the right posterior shoulder—revealed verrucous keratosis pathology (Figure 2). At this time, encorafenib was increased again to 300 mg/d as the patient had been tolerating the reduced dose. She continued to report the appearance of new lesions for the next 3 months, after which the lesions were stable for approximately 2 months. By 2.5 months after initiation of therapy, the patient had undergone CT demonstrating resolution of the liver lesions. At 5 months of therapy, the patient reported a stable to slightly reduced number of skin lesions but had begun to experience worsening joint pain, and the dosage of encorafenib was reduced to 225 mg/d. At 7 months of therapy, the dosage was further reduced to 150 mg/d due to persistent arthralgia. A follow-up examination at 10 months of therapy showed improvement in the number and size of the verrucous keratoses, and near resolution was seen by 14 months after the initial onset of the lesions (Figure 1B). At 20 months after initial onset, only 1 remaining verrucous keratosis was identified on physical examination and biopsy. The patient had continued a regimen of encorafenib 150 mg/d and weekly intravenous 500 mg cetuximab up to this point. Over the entire time period that the patient was seen, up to 12 lesions located in high-friction areas had become irritated and were treated with cryotherapy, but this contributed only minorly to the patient’s overall presentation.

Verrucous keratosis is a known cutaneous AE of BRAF inhibitor treatment with vemurafenib and dabrafenib, with fewer cases attributed to encorafenib.5,6 Within the oncologic setting, the eruption of verrucous papules as a paraneoplastic phenomenon is heavily debated in the literature and is known as the Leser-Trélat sign. This phenomenon is commonly associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, as seen in our patient.10 Based on Curth’s postulates—the criteria used to evaluate the relationship between an internal malignancy and a cutaneous disorder—this was unlikely in our patient. The criteria, which do not all need to be met to suggest a paraneoplastic phenomenon, include concurrent onset of the malignancy and the dermatosis, parallel course, association of a specific dermatosis with a specific malignancy, statistical significance of the association, and the presence of a genetic basis for the association.11 Several features favored a drug-related cutaneous eruption vs a paraneoplastic phenomenon: (1) the malignancy was identified months before the cutaneous eruptions manifested; (2) the cutaneous lesions appeared once treatment had already been initiated; and (3) the cutaneous lesions persisted long after the malignancy was no longer identifiable on CT. Indeed, eruption of the papules temporally coincided closely with the initiation of BRAF inhibitor therapy, arguing for correlation.

As a suspected BRAF inhibitor–associated cutaneous AE, the eruption of verrucous keratoses in our patient is remarkable for its spontaneous resolution despite ongoing therapy. It is speculated that keratinocytic proliferation while on BRAF inhibitor therapy may be caused by a paradoxical increase in signaling through CRAF, another Raf isoform that plays a role in the induction of terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, with a subsequent increase in MAPK signaling.12-14 Self-resolution of this cycle despite continuing BRAF inhibitor therapy suggests the possible involvement of balancing and/or alternative mechanistic pathways that may be related to the immune system. Although verrucous keratoses are considered benign proliferations and do not necessarily require any specific treatment or reduction in BRAF inhibitor dosage, they may be treated with cryotherapy, electrocautery, shave removal, or excision,15 which often is done if the lesions become inflamed and cause pain. Additionally, some patients may feel distress from the appearance of the lesions and desire treatment for this reason. Understanding that verrucous keratoses can be a transient cutaneous AE rather than a persistent one may be useful to clinicians as they manage AEs during BRAF inhibitor therapy.

- Pakneshan S, Salajegheh A, Smith RA, Lam AK. Clinicopathological relevance of BRAF mutations in human cancer. Pathology. 2013;45:346-356. doi:10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360b61d

- Dhomen N, Marais R. BRAF signaling and targeted therapies in melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:529-545. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2009.04.001

- Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239-1246. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327

- Ji Z, Flaherty KT, Tsao H. Targeting the RAS pathway in melanoma. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:27-35. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.001

- Gouda MA, Subbiah V. Precision oncology for BRAF-mutant cancers with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: from melanoma to tissue-agnostic therapy. ESMO Open. 2023;8:100788. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100788

- Gençler B, Gönül M. Cutaneous side effects of BRAF inhibitors in advanced melanoma: review of the literature. Dermatol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5361569. doi:10.1155/2016/5361569.

- Chu EY, Wanat KA, Miller CJ, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1265-1272. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.008

- Naqash AR, File DM, Ziemer CM, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions in B-RAF positive metastatic melanoma following sequential treatment with B-RAF/MEK inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade or vice versa. a single-institutional case-series. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:4. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0475-y

- Maldonado-Seral C, Berros-Fombella JP, Vivanco-Allende B, et al. Vemurafenib-associated neutrophilic panniculitis: an emergent adverse effect of variable severity. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:16. doi:10.5070/d370x41670

- Mirali S, Mufti A, Lansang RP, et al. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses are associated with a co-occurring malignancy in the majority of reported cases: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26:57-62. doi:10.1177/12034754211035124

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98. doi:10.3322/caac.20005

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435. doi:10.1038/nature08833

- Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209-221. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, et al. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signaling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427-430. doi:10.1038/nature08902

- Hayat MA. Brain Metastases from Primary Tumors, Volume 3: Epidemiology, Biology, and Therapy of Melanoma and Other Cancers. Academic Press; 2016.

To the Editor:

Mutations of the BRAF protein kinase gene are implicated in a variety of malignancies.1 BRAF mutations in malignancies cause the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to become constitutively active, which results in unchecked cellular proliferation,2,3 making the BRAF mutation an attractive target for inhibition with pharmacologic agents to potentially halt cancer growth.4 Vemurafenib—the first selective BRAF inhibitor used in clinical practice—initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2011. The approval of dabrafenib followed in 2013 and most recently encorafenib in 2018.5

Although targeted treatment of BRAF-mutated malignancies with BRAF inhibitors has become common, it often is associated with cutaneous adverse events (AEs), such as rash, pruritus, photosensitivity, actinic keratosis, and verrucous keratosis. Some reports demonstrate these events in up to 95% of patients undergoing BRAF inhibitor treatment.6 In several cases the eruption of verrucous keratoses is among the most common cutaneous AEs seen among patients receiving BRAF inhibitor treatment.5-7

In general, lesions can appear days to months after therapy is initiated and may resolve after switching to dual therapy with a MEK inhibitor or with complete cessation of BRAF inhibitor therapy.5,7,8 One case of spontaneous resolution of vemurafenib-associated panniculitis during ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy has been reported9; however, spontaneous resolution of cutaneous AEs is uncommon. Herein, we describe verrucous keratoses in a patient undergoing treatment with encorafenib that resolved spontaneously despite ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy.

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with pain in the right lower quadrant. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large ovarian mass. Subsequent bloodwork revealed elevated carcinoembryonic antigen levels. The patient underwent a hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse side-to-side anastomosis, right pelvic lymph node reduction, and complete cytoreduction. Histopathology revealed an adenocarcinoma of the cecum with tumor invasion into the visceral peritoneum and metastases to the left ovary, fallopian tube, and omentum. A BRAF V600E mutation was detected.

Two months after the initial presentation, the patient started her first cycle of chemotherapy with a combination of folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. She completed 11 cycles of this regimen, then was switched to capecitabine and oxaliplatin for an additional 2 cycles due to insurance concerns. At the end of treatment, there was no evidence of disease on CT, thus the patient was followed with observation. However, she presented 10 months later to the emergency department with abdominal pain, and CT revealed new lesions in the liver that were concerning for potential metastases. She started oral encorafenib 300 mg/d and intravenous cetuximab 500 mg weekly; after 1 week, encorafenib was reduced to 150 mg/d due to nausea and loss of appetite. Within 2 weeks of starting treatment, the patient reported the relatively abrupt appearance of more than 50 small papules across the shoulders and back (Figure 1A). She was referred to dermatology, and shave biopsies of 2 lesions—one from the left anterior thigh, the other from the right posterior shoulder—revealed verrucous keratosis pathology (Figure 2). At this time, encorafenib was increased again to 300 mg/d as the patient had been tolerating the reduced dose. She continued to report the appearance of new lesions for the next 3 months, after which the lesions were stable for approximately 2 months. By 2.5 months after initiation of therapy, the patient had undergone CT demonstrating resolution of the liver lesions. At 5 months of therapy, the patient reported a stable to slightly reduced number of skin lesions but had begun to experience worsening joint pain, and the dosage of encorafenib was reduced to 225 mg/d. At 7 months of therapy, the dosage was further reduced to 150 mg/d due to persistent arthralgia. A follow-up examination at 10 months of therapy showed improvement in the number and size of the verrucous keratoses, and near resolution was seen by 14 months after the initial onset of the lesions (Figure 1B). At 20 months after initial onset, only 1 remaining verrucous keratosis was identified on physical examination and biopsy. The patient had continued a regimen of encorafenib 150 mg/d and weekly intravenous 500 mg cetuximab up to this point. Over the entire time period that the patient was seen, up to 12 lesions located in high-friction areas had become irritated and were treated with cryotherapy, but this contributed only minorly to the patient’s overall presentation.

Verrucous keratosis is a known cutaneous AE of BRAF inhibitor treatment with vemurafenib and dabrafenib, with fewer cases attributed to encorafenib.5,6 Within the oncologic setting, the eruption of verrucous papules as a paraneoplastic phenomenon is heavily debated in the literature and is known as the Leser-Trélat sign. This phenomenon is commonly associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, as seen in our patient.10 Based on Curth’s postulates—the criteria used to evaluate the relationship between an internal malignancy and a cutaneous disorder—this was unlikely in our patient. The criteria, which do not all need to be met to suggest a paraneoplastic phenomenon, include concurrent onset of the malignancy and the dermatosis, parallel course, association of a specific dermatosis with a specific malignancy, statistical significance of the association, and the presence of a genetic basis for the association.11 Several features favored a drug-related cutaneous eruption vs a paraneoplastic phenomenon: (1) the malignancy was identified months before the cutaneous eruptions manifested; (2) the cutaneous lesions appeared once treatment had already been initiated; and (3) the cutaneous lesions persisted long after the malignancy was no longer identifiable on CT. Indeed, eruption of the papules temporally coincided closely with the initiation of BRAF inhibitor therapy, arguing for correlation.

As a suspected BRAF inhibitor–associated cutaneous AE, the eruption of verrucous keratoses in our patient is remarkable for its spontaneous resolution despite ongoing therapy. It is speculated that keratinocytic proliferation while on BRAF inhibitor therapy may be caused by a paradoxical increase in signaling through CRAF, another Raf isoform that plays a role in the induction of terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, with a subsequent increase in MAPK signaling.12-14 Self-resolution of this cycle despite continuing BRAF inhibitor therapy suggests the possible involvement of balancing and/or alternative mechanistic pathways that may be related to the immune system. Although verrucous keratoses are considered benign proliferations and do not necessarily require any specific treatment or reduction in BRAF inhibitor dosage, they may be treated with cryotherapy, electrocautery, shave removal, or excision,15 which often is done if the lesions become inflamed and cause pain. Additionally, some patients may feel distress from the appearance of the lesions and desire treatment for this reason. Understanding that verrucous keratoses can be a transient cutaneous AE rather than a persistent one may be useful to clinicians as they manage AEs during BRAF inhibitor therapy.

To the Editor:

Mutations of the BRAF protein kinase gene are implicated in a variety of malignancies.1 BRAF mutations in malignancies cause the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to become constitutively active, which results in unchecked cellular proliferation,2,3 making the BRAF mutation an attractive target for inhibition with pharmacologic agents to potentially halt cancer growth.4 Vemurafenib—the first selective BRAF inhibitor used in clinical practice—initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2011. The approval of dabrafenib followed in 2013 and most recently encorafenib in 2018.5

Although targeted treatment of BRAF-mutated malignancies with BRAF inhibitors has become common, it often is associated with cutaneous adverse events (AEs), such as rash, pruritus, photosensitivity, actinic keratosis, and verrucous keratosis. Some reports demonstrate these events in up to 95% of patients undergoing BRAF inhibitor treatment.6 In several cases the eruption of verrucous keratoses is among the most common cutaneous AEs seen among patients receiving BRAF inhibitor treatment.5-7

In general, lesions can appear days to months after therapy is initiated and may resolve after switching to dual therapy with a MEK inhibitor or with complete cessation of BRAF inhibitor therapy.5,7,8 One case of spontaneous resolution of vemurafenib-associated panniculitis during ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy has been reported9; however, spontaneous resolution of cutaneous AEs is uncommon. Herein, we describe verrucous keratoses in a patient undergoing treatment with encorafenib that resolved spontaneously despite ongoing BRAF inhibitor therapy.

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with pain in the right lower quadrant. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large ovarian mass. Subsequent bloodwork revealed elevated carcinoembryonic antigen levels. The patient underwent a hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse side-to-side anastomosis, right pelvic lymph node reduction, and complete cytoreduction. Histopathology revealed an adenocarcinoma of the cecum with tumor invasion into the visceral peritoneum and metastases to the left ovary, fallopian tube, and omentum. A BRAF V600E mutation was detected.

Two months after the initial presentation, the patient started her first cycle of chemotherapy with a combination of folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. She completed 11 cycles of this regimen, then was switched to capecitabine and oxaliplatin for an additional 2 cycles due to insurance concerns. At the end of treatment, there was no evidence of disease on CT, thus the patient was followed with observation. However, she presented 10 months later to the emergency department with abdominal pain, and CT revealed new lesions in the liver that were concerning for potential metastases. She started oral encorafenib 300 mg/d and intravenous cetuximab 500 mg weekly; after 1 week, encorafenib was reduced to 150 mg/d due to nausea and loss of appetite. Within 2 weeks of starting treatment, the patient reported the relatively abrupt appearance of more than 50 small papules across the shoulders and back (Figure 1A). She was referred to dermatology, and shave biopsies of 2 lesions—one from the left anterior thigh, the other from the right posterior shoulder—revealed verrucous keratosis pathology (Figure 2). At this time, encorafenib was increased again to 300 mg/d as the patient had been tolerating the reduced dose. She continued to report the appearance of new lesions for the next 3 months, after which the lesions were stable for approximately 2 months. By 2.5 months after initiation of therapy, the patient had undergone CT demonstrating resolution of the liver lesions. At 5 months of therapy, the patient reported a stable to slightly reduced number of skin lesions but had begun to experience worsening joint pain, and the dosage of encorafenib was reduced to 225 mg/d. At 7 months of therapy, the dosage was further reduced to 150 mg/d due to persistent arthralgia. A follow-up examination at 10 months of therapy showed improvement in the number and size of the verrucous keratoses, and near resolution was seen by 14 months after the initial onset of the lesions (Figure 1B). At 20 months after initial onset, only 1 remaining verrucous keratosis was identified on physical examination and biopsy. The patient had continued a regimen of encorafenib 150 mg/d and weekly intravenous 500 mg cetuximab up to this point. Over the entire time period that the patient was seen, up to 12 lesions located in high-friction areas had become irritated and were treated with cryotherapy, but this contributed only minorly to the patient’s overall presentation.

Verrucous keratosis is a known cutaneous AE of BRAF inhibitor treatment with vemurafenib and dabrafenib, with fewer cases attributed to encorafenib.5,6 Within the oncologic setting, the eruption of verrucous papules as a paraneoplastic phenomenon is heavily debated in the literature and is known as the Leser-Trélat sign. This phenomenon is commonly associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, as seen in our patient.10 Based on Curth’s postulates—the criteria used to evaluate the relationship between an internal malignancy and a cutaneous disorder—this was unlikely in our patient. The criteria, which do not all need to be met to suggest a paraneoplastic phenomenon, include concurrent onset of the malignancy and the dermatosis, parallel course, association of a specific dermatosis with a specific malignancy, statistical significance of the association, and the presence of a genetic basis for the association.11 Several features favored a drug-related cutaneous eruption vs a paraneoplastic phenomenon: (1) the malignancy was identified months before the cutaneous eruptions manifested; (2) the cutaneous lesions appeared once treatment had already been initiated; and (3) the cutaneous lesions persisted long after the malignancy was no longer identifiable on CT. Indeed, eruption of the papules temporally coincided closely with the initiation of BRAF inhibitor therapy, arguing for correlation.

As a suspected BRAF inhibitor–associated cutaneous AE, the eruption of verrucous keratoses in our patient is remarkable for its spontaneous resolution despite ongoing therapy. It is speculated that keratinocytic proliferation while on BRAF inhibitor therapy may be caused by a paradoxical increase in signaling through CRAF, another Raf isoform that plays a role in the induction of terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, with a subsequent increase in MAPK signaling.12-14 Self-resolution of this cycle despite continuing BRAF inhibitor therapy suggests the possible involvement of balancing and/or alternative mechanistic pathways that may be related to the immune system. Although verrucous keratoses are considered benign proliferations and do not necessarily require any specific treatment or reduction in BRAF inhibitor dosage, they may be treated with cryotherapy, electrocautery, shave removal, or excision,15 which often is done if the lesions become inflamed and cause pain. Additionally, some patients may feel distress from the appearance of the lesions and desire treatment for this reason. Understanding that verrucous keratoses can be a transient cutaneous AE rather than a persistent one may be useful to clinicians as they manage AEs during BRAF inhibitor therapy.

- Pakneshan S, Salajegheh A, Smith RA, Lam AK. Clinicopathological relevance of BRAF mutations in human cancer. Pathology. 2013;45:346-356. doi:10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360b61d

- Dhomen N, Marais R. BRAF signaling and targeted therapies in melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:529-545. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2009.04.001

- Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239-1246. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327

- Ji Z, Flaherty KT, Tsao H. Targeting the RAS pathway in melanoma. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:27-35. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.001

- Gouda MA, Subbiah V. Precision oncology for BRAF-mutant cancers with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: from melanoma to tissue-agnostic therapy. ESMO Open. 2023;8:100788. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100788

- Gençler B, Gönül M. Cutaneous side effects of BRAF inhibitors in advanced melanoma: review of the literature. Dermatol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5361569. doi:10.1155/2016/5361569.

- Chu EY, Wanat KA, Miller CJ, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1265-1272. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.008

- Naqash AR, File DM, Ziemer CM, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions in B-RAF positive metastatic melanoma following sequential treatment with B-RAF/MEK inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade or vice versa. a single-institutional case-series. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:4. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0475-y

- Maldonado-Seral C, Berros-Fombella JP, Vivanco-Allende B, et al. Vemurafenib-associated neutrophilic panniculitis: an emergent adverse effect of variable severity. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:16. doi:10.5070/d370x41670

- Mirali S, Mufti A, Lansang RP, et al. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses are associated with a co-occurring malignancy in the majority of reported cases: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26:57-62. doi:10.1177/12034754211035124

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98. doi:10.3322/caac.20005

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435. doi:10.1038/nature08833

- Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209-221. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, et al. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signaling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427-430. doi:10.1038/nature08902

- Hayat MA. Brain Metastases from Primary Tumors, Volume 3: Epidemiology, Biology, and Therapy of Melanoma and Other Cancers. Academic Press; 2016.

- Pakneshan S, Salajegheh A, Smith RA, Lam AK. Clinicopathological relevance of BRAF mutations in human cancer. Pathology. 2013;45:346-356. doi:10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360b61d

- Dhomen N, Marais R. BRAF signaling and targeted therapies in melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:529-545. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2009.04.001

- Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239-1246. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327

- Ji Z, Flaherty KT, Tsao H. Targeting the RAS pathway in melanoma. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:27-35. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.001

- Gouda MA, Subbiah V. Precision oncology for BRAF-mutant cancers with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: from melanoma to tissue-agnostic therapy. ESMO Open. 2023;8:100788. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100788

- Gençler B, Gönül M. Cutaneous side effects of BRAF inhibitors in advanced melanoma: review of the literature. Dermatol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5361569. doi:10.1155/2016/5361569.

- Chu EY, Wanat KA, Miller CJ, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1265-1272. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.008

- Naqash AR, File DM, Ziemer CM, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions in B-RAF positive metastatic melanoma following sequential treatment with B-RAF/MEK inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade or vice versa. a single-institutional case-series. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:4. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0475-y

- Maldonado-Seral C, Berros-Fombella JP, Vivanco-Allende B, et al. Vemurafenib-associated neutrophilic panniculitis: an emergent adverse effect of variable severity. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:16. doi:10.5070/d370x41670

- Mirali S, Mufti A, Lansang RP, et al. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses are associated with a co-occurring malignancy in the majority of reported cases: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26:57-62. doi:10.1177/12034754211035124

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98. doi:10.3322/caac.20005

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435. doi:10.1038/nature08833

- Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209-221. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, et al. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signaling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427-430. doi:10.1038/nature08902

- Hayat MA. Brain Metastases from Primary Tumors, Volume 3: Epidemiology, Biology, and Therapy of Melanoma and Other Cancers. Academic Press; 2016.

Practice Points

- Verrucous keratoses are common cutaneous adverse events (AEs) associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy.

- Verrucous papules may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon and can be differentiated from a treatment-related AE based on the timing and progression in relation to tumor burden.

- Although treatment of particularly bothersome lesions with cryotherapy may be warranted, verrucous papules secondary to BRAF inhibitor therapy may resolve spontaneously.

Rare Case of Photodistributed Hyperpigmentation Linked to Kratom Consumption

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

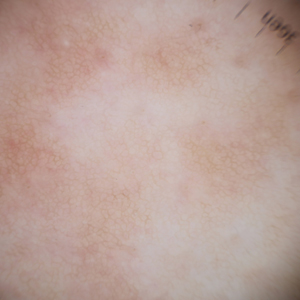

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

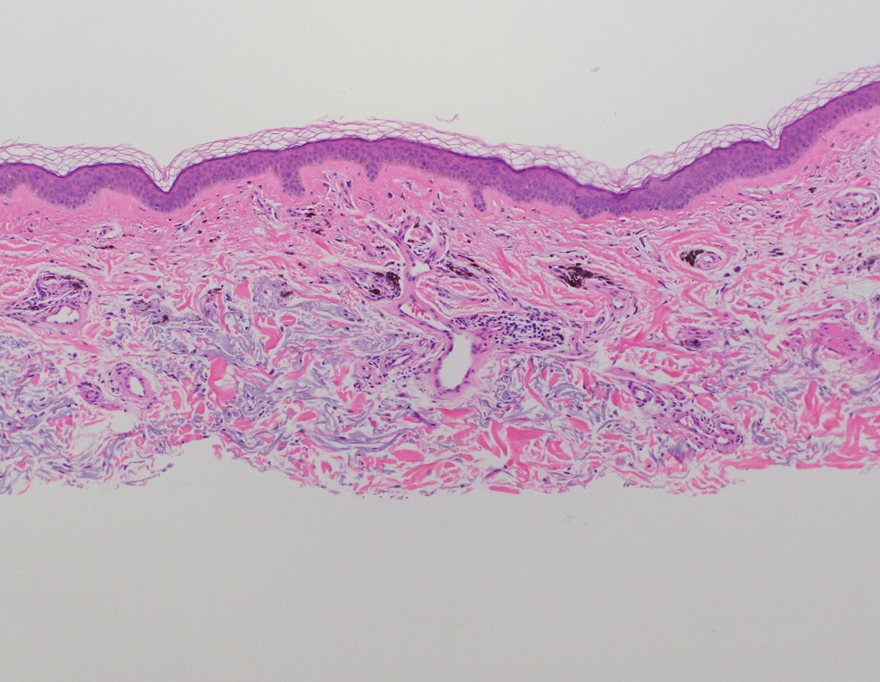

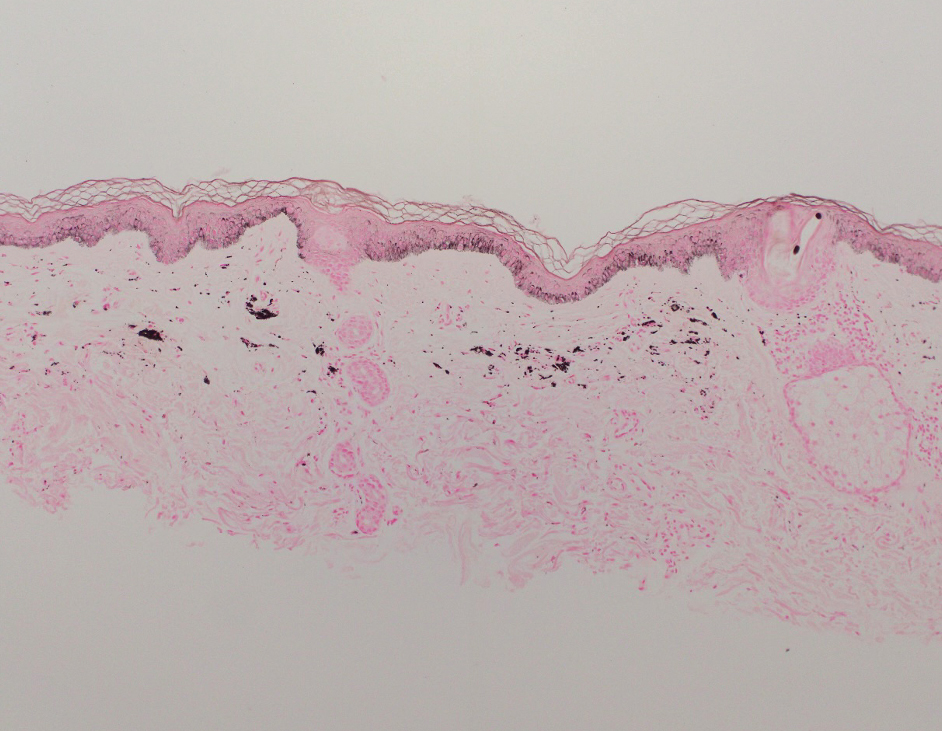

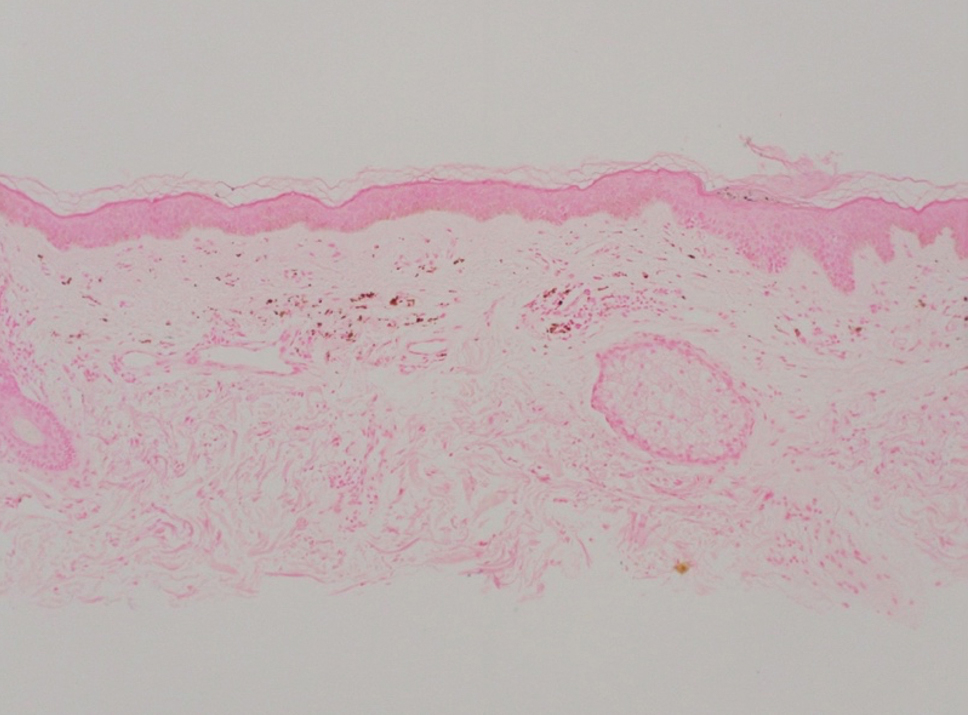

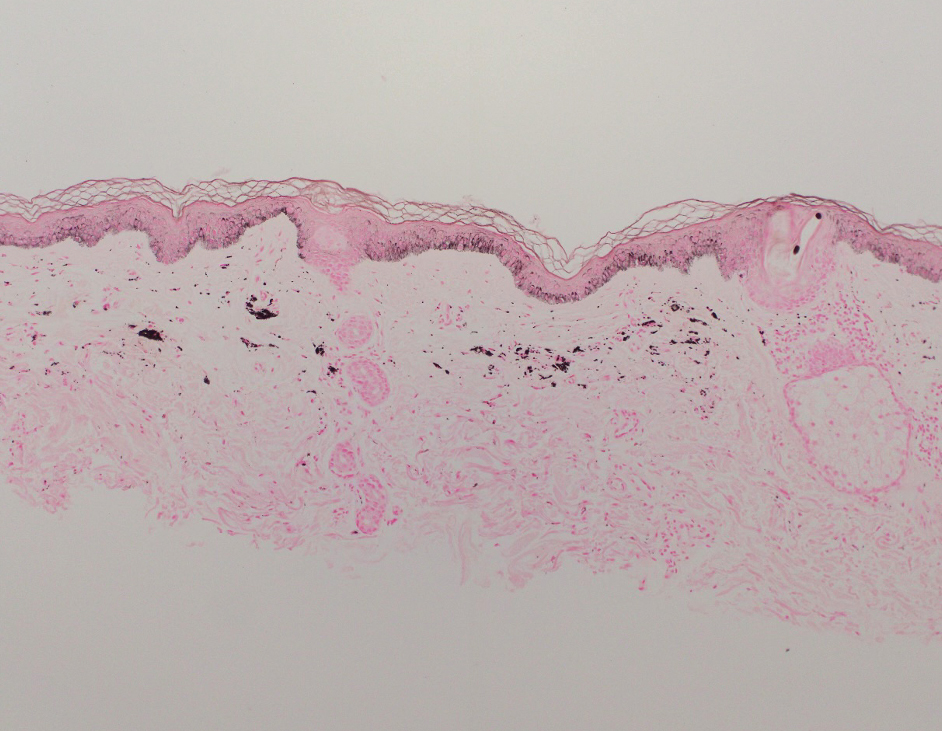

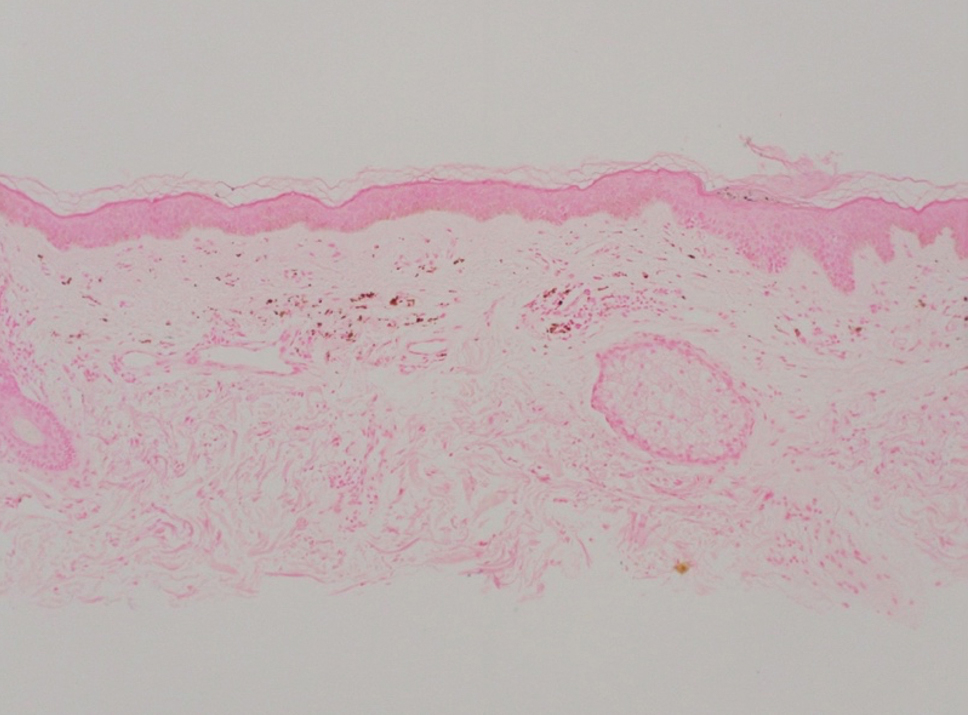

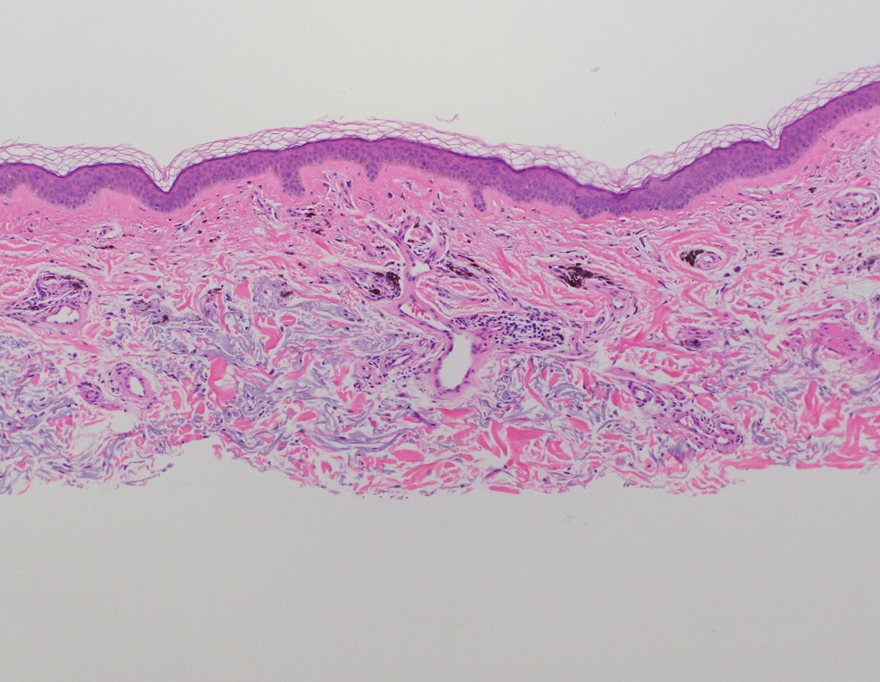

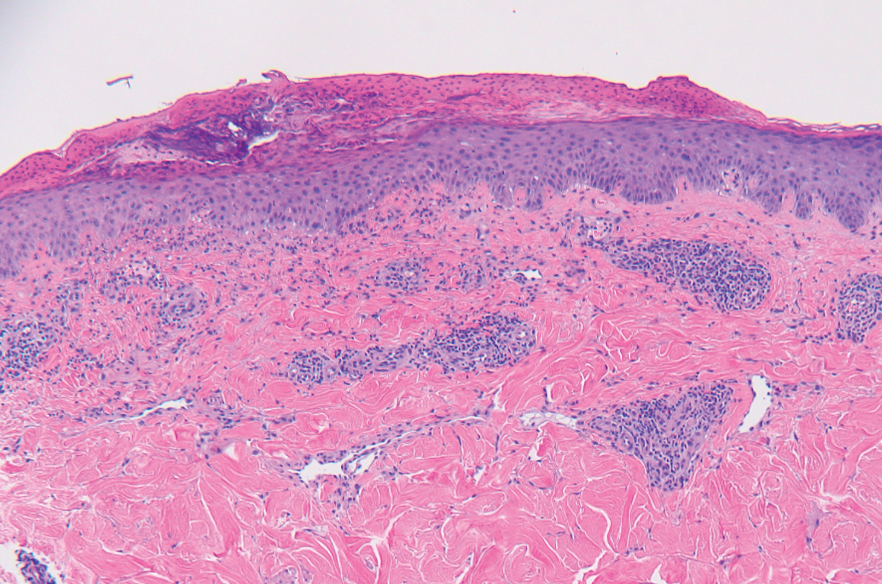

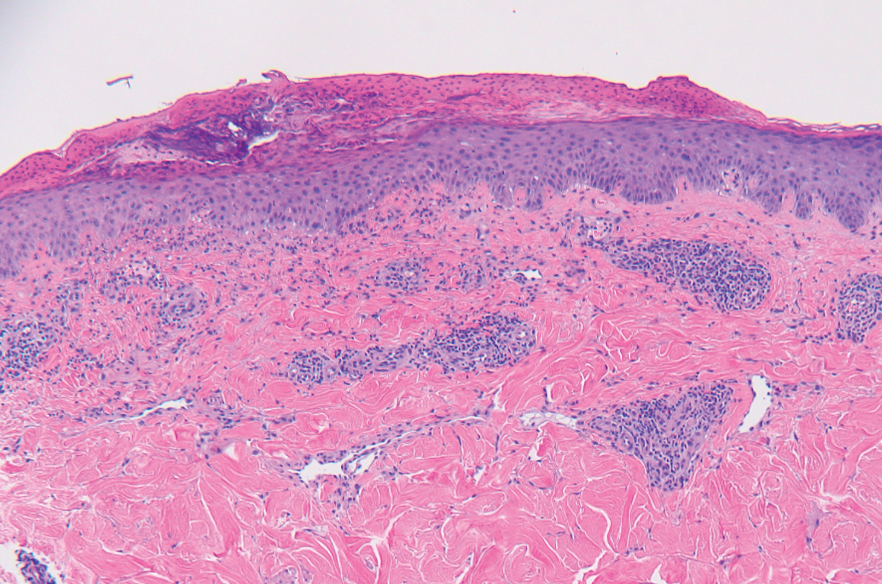

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

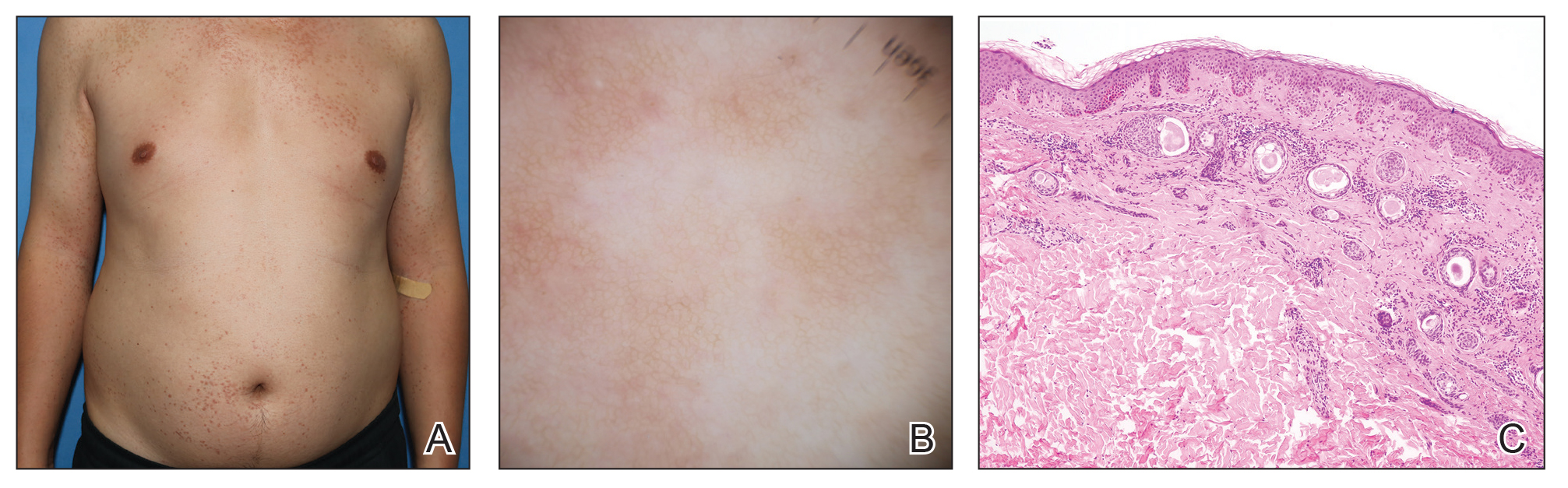

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

Practice Points

- Clinicians should be aware of photodistributed hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse effect of kratom usage.

- Kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation should be suspected in patients with hyperpigmented lesions in sun-exposed areas of the skin following kratom use. A biopsy of lesions should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

- Cessation of kratom should be recommended.

Successful Treatment of Refractory Extensive Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris With Risankizumab and Acitretin

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.

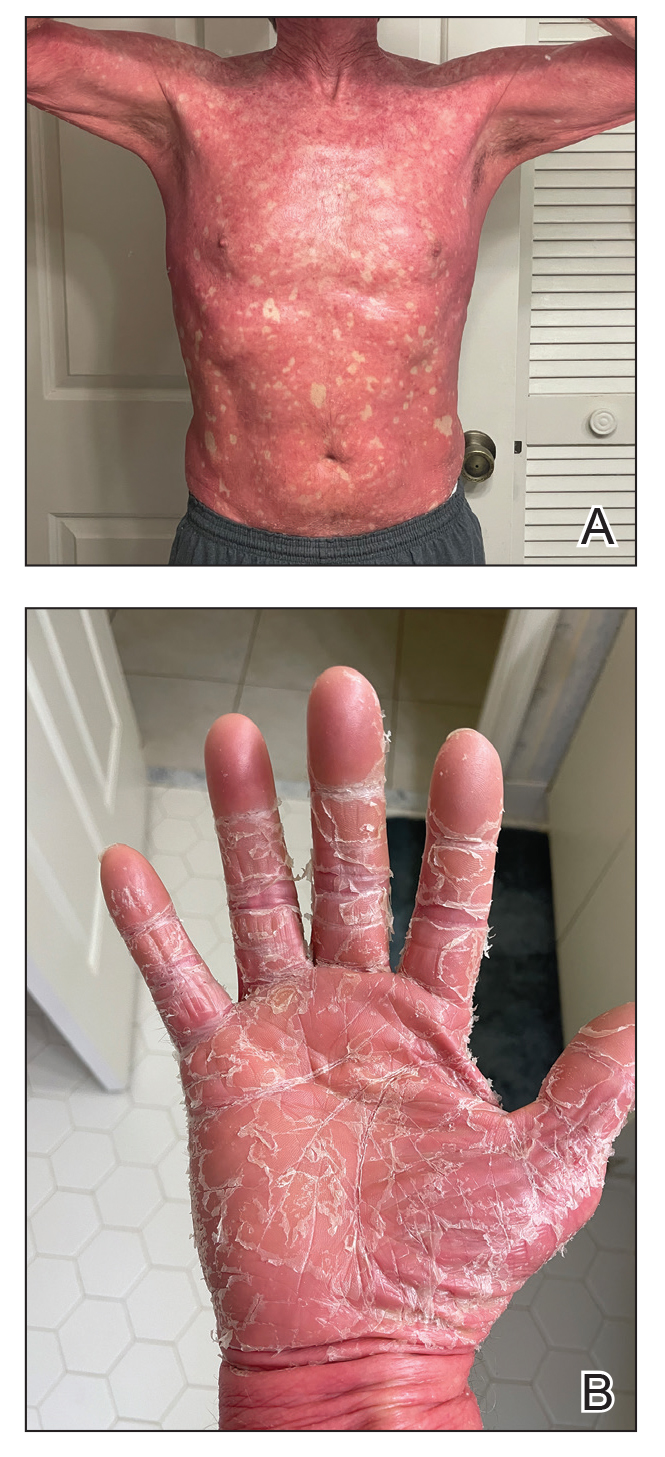

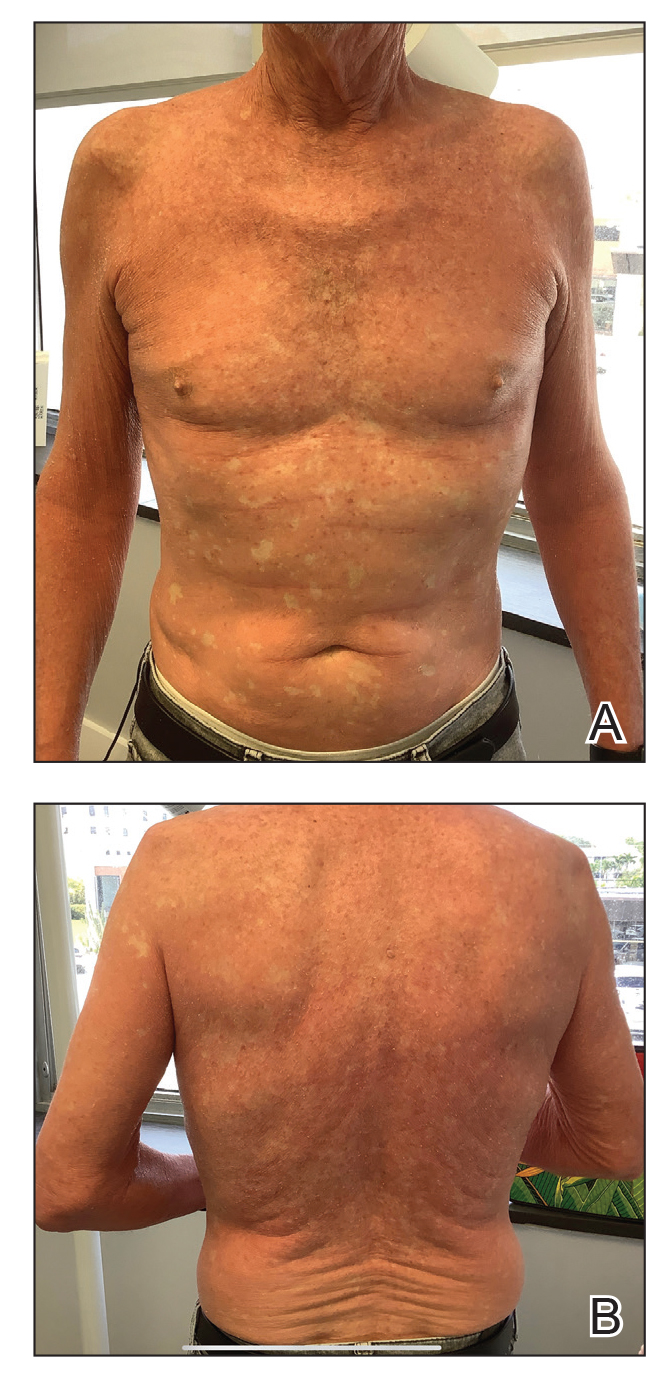

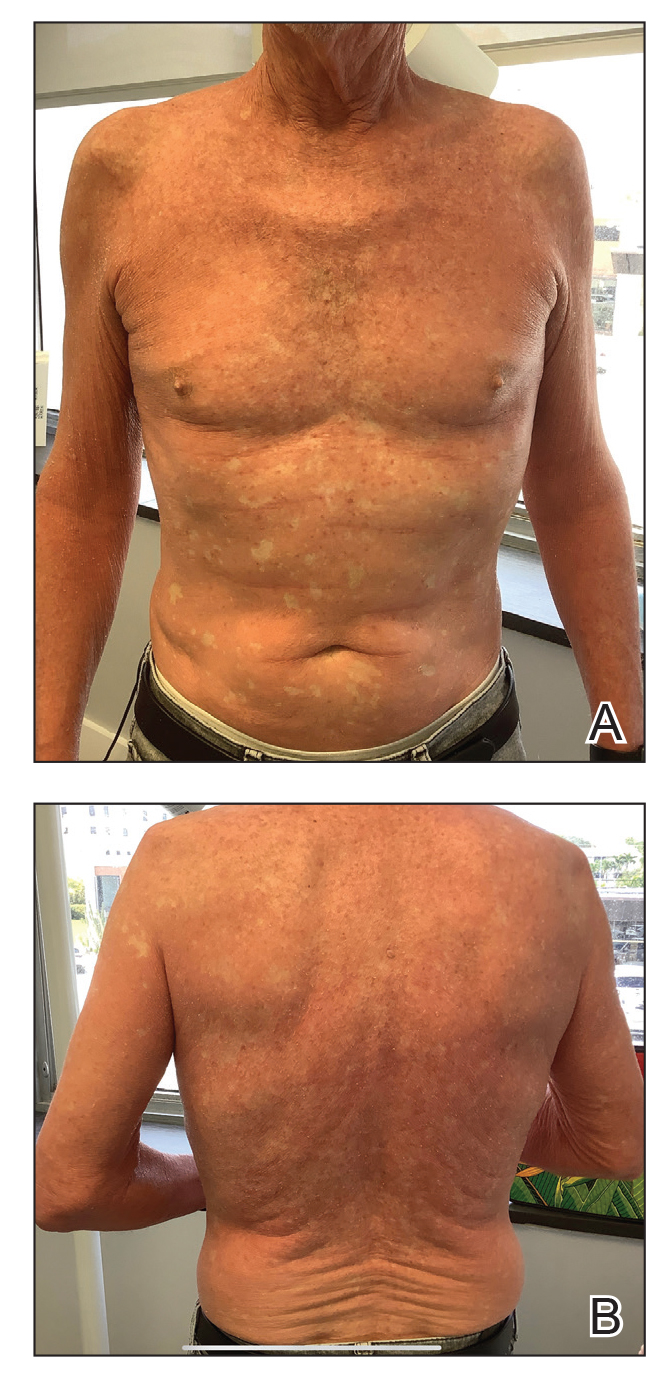

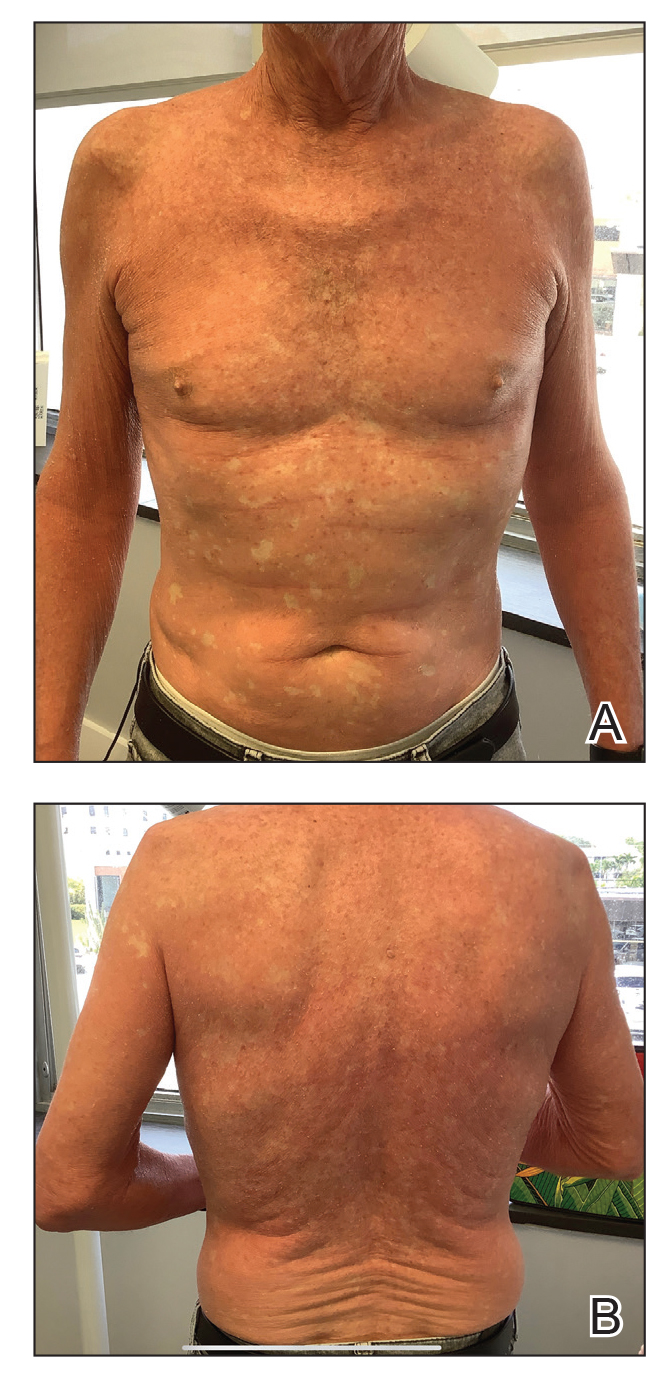

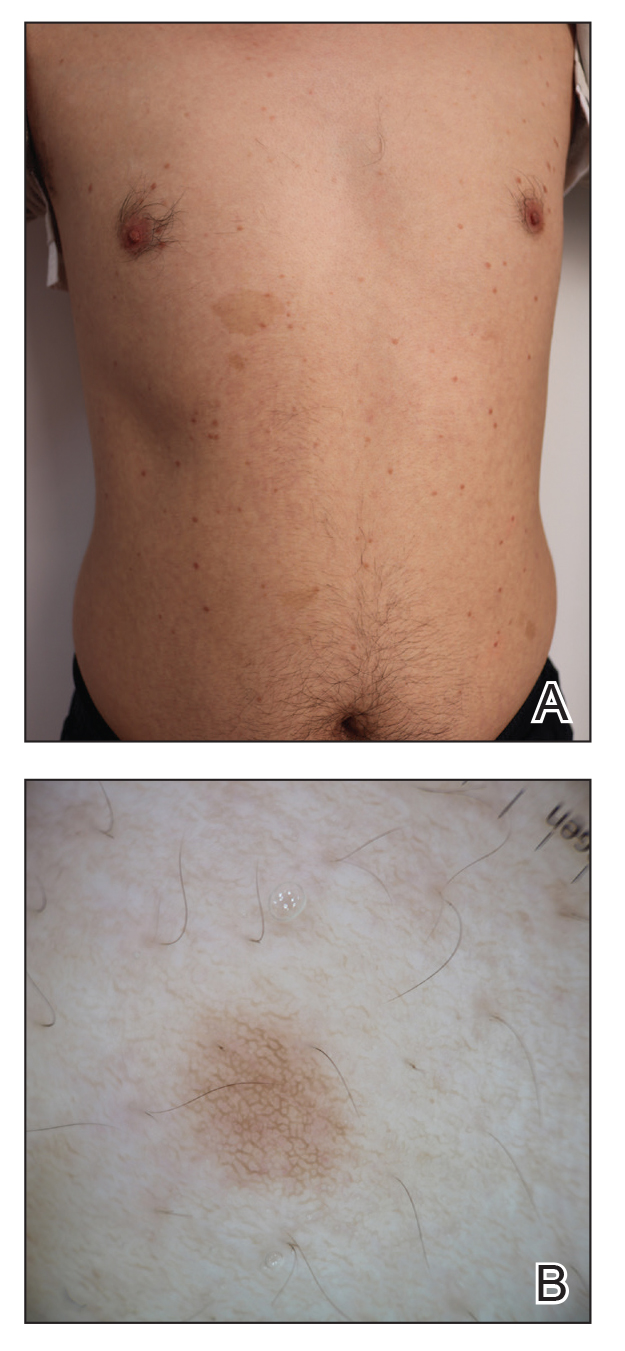

A 65-year-old man was referred to Florida Academic Dermatology Center (Coral Gables, Florida) with biopsy-proven PRP diagnosed 1 year prior. The patient reported experiencing a debilitating quality of life in the year since diagnosis (Figure 1). Treatment attempts with dupilumab, tralokinumab, intramuscular steroid injections, and topical corticosteroids had failed (Figure 2). Following evaluation at Florida Academic Dermatology Center, the patient was started on acitretin 25 mg every other day and received an initial subcutaneous injection of ixekizumab 160 mg (an IL-17 inhibitor) followed 2 weeks later by a second injection of 80 mg. After the 2 doses of ixekizumab, the patient’s condition worsened with the development of pinpoint hemorrhagic lesions. The medication was discontinued, and he was started on risankizumab 150 mg at the approved dosing regimen for plaque psoriasis in combination with the acitretin therapy. Prior to starting risankizumab, the affected body surface area (BSA) was 80%. At 1-month follow-up, he showed improvement with reduction in scaling and erythema and an affected BSA of 30% (Figure 3). At 4-month follow-up, he continued showing improvement with an affected BSA of 10% (Figure 4). Acitretin was discontinued, and the patient has been successfully maintained on risankizumab 150 mg/mL subcutaneous injections every 12 weeks since.

Oral retinoid therapy historically was considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe PRP. A systematic review (N=105) of retinoid therapies showed 83% of patients with PRP who were treated with acitretin plus biologic therapy had a favorable response, whereas only 36% of patients treated with acitretin as monotherapy had the same response, highlighting the importance of dual therapy.3 The use of ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) for refractory PRP has been well documented, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms risankizumab and pityriasis rubra pilaris yielded only 8 published cases of risankizumab for treatment of PRP.4-8 All patients were diagnosed with refractory PRP, and multiple treatment modalities failed.

Ustekinumab has been shown to create a rapid response and maintain it long term, especially in patients with type 1 PRP who did not respond to systemic therapies or anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.2 An open-label, single-arm clinical trial found secukinumab was an effective therapy for PRP and demonstrated transcription heterogeneity of this dermatologic condition.9 The researchers proposed that some patients may respond to IL-17 inhibitors but others may not due to the differences in RNA molecules transcribed.9 Our patient demonstrated worsening of his condition with an IL-17 inhibitor but experienced remarkable improvement with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor.

Risankizumab is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. This humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its role in the pathogenic helper T cell (TH17) pathway. Research has shown that it is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modality for psoriatic conditions.10 It is well known that PRP and psoriasis have similar cytokine activations; therefore, we propose that combination therapy with risankizumab and acitretin may show promise for refractory PRP.

- Gelmetti C, Schiuma AA, Cerri D, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in childhood: a long-term study of 29 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:446-451. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00648.x

- Moretta G, De Luca EV, Di Stefani A. Management of refractory pityriasis rubra pilaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:451-457. doi:10.2147/CCID.S124351

- Engelmann C, Elsner P, Miguel D. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris type I: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:524-537. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3641

- Ricar J, Cetkovska P. Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E148. doi:10.1111/bjd.19681

- Brocco E, Laffitte E. Risankizumab for pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1322-1324. doi:10.1111/ced.14715

- Duarte B, Paiva Lopes MJ. Response to: ‘Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab.’ Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:235-236. doi:10.1111/bjd.20061

- Kromer C, Schön MP, Mössner R. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:1207-1209. doi:10.1111/ddg.14504

- Kołt-Kamińska M, Osińska A, Kaznowska E, et al. Successful treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in children. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2431-2441. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01005-y

- Boudreaux BW, Pincelli TP, Bhullar PK, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris: a single-arm clinical trial with transcriptomic analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:650-658. doi:10.1111/bjd.21708

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi CL, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous risankizumab therapy vs treatment withdrawal in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:649-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0723

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.

A 65-year-old man was referred to Florida Academic Dermatology Center (Coral Gables, Florida) with biopsy-proven PRP diagnosed 1 year prior. The patient reported experiencing a debilitating quality of life in the year since diagnosis (Figure 1). Treatment attempts with dupilumab, tralokinumab, intramuscular steroid injections, and topical corticosteroids had failed (Figure 2). Following evaluation at Florida Academic Dermatology Center, the patient was started on acitretin 25 mg every other day and received an initial subcutaneous injection of ixekizumab 160 mg (an IL-17 inhibitor) followed 2 weeks later by a second injection of 80 mg. After the 2 doses of ixekizumab, the patient’s condition worsened with the development of pinpoint hemorrhagic lesions. The medication was discontinued, and he was started on risankizumab 150 mg at the approved dosing regimen for plaque psoriasis in combination with the acitretin therapy. Prior to starting risankizumab, the affected body surface area (BSA) was 80%. At 1-month follow-up, he showed improvement with reduction in scaling and erythema and an affected BSA of 30% (Figure 3). At 4-month follow-up, he continued showing improvement with an affected BSA of 10% (Figure 4). Acitretin was discontinued, and the patient has been successfully maintained on risankizumab 150 mg/mL subcutaneous injections every 12 weeks since.

Oral retinoid therapy historically was considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe PRP. A systematic review (N=105) of retinoid therapies showed 83% of patients with PRP who were treated with acitretin plus biologic therapy had a favorable response, whereas only 36% of patients treated with acitretin as monotherapy had the same response, highlighting the importance of dual therapy.3 The use of ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) for refractory PRP has been well documented, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms risankizumab and pityriasis rubra pilaris yielded only 8 published cases of risankizumab for treatment of PRP.4-8 All patients were diagnosed with refractory PRP, and multiple treatment modalities failed.

Ustekinumab has been shown to create a rapid response and maintain it long term, especially in patients with type 1 PRP who did not respond to systemic therapies or anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.2 An open-label, single-arm clinical trial found secukinumab was an effective therapy for PRP and demonstrated transcription heterogeneity of this dermatologic condition.9 The researchers proposed that some patients may respond to IL-17 inhibitors but others may not due to the differences in RNA molecules transcribed.9 Our patient demonstrated worsening of his condition with an IL-17 inhibitor but experienced remarkable improvement with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor.

Risankizumab is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. This humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its role in the pathogenic helper T cell (TH17) pathway. Research has shown that it is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modality for psoriatic conditions.10 It is well known that PRP and psoriasis have similar cytokine activations; therefore, we propose that combination therapy with risankizumab and acitretin may show promise for refractory PRP.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.