User login

Child of The New Gastroenterologist

Underserved populations and colorectal cancer screening: Patient perceptions of barriers to care and effective interventions

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

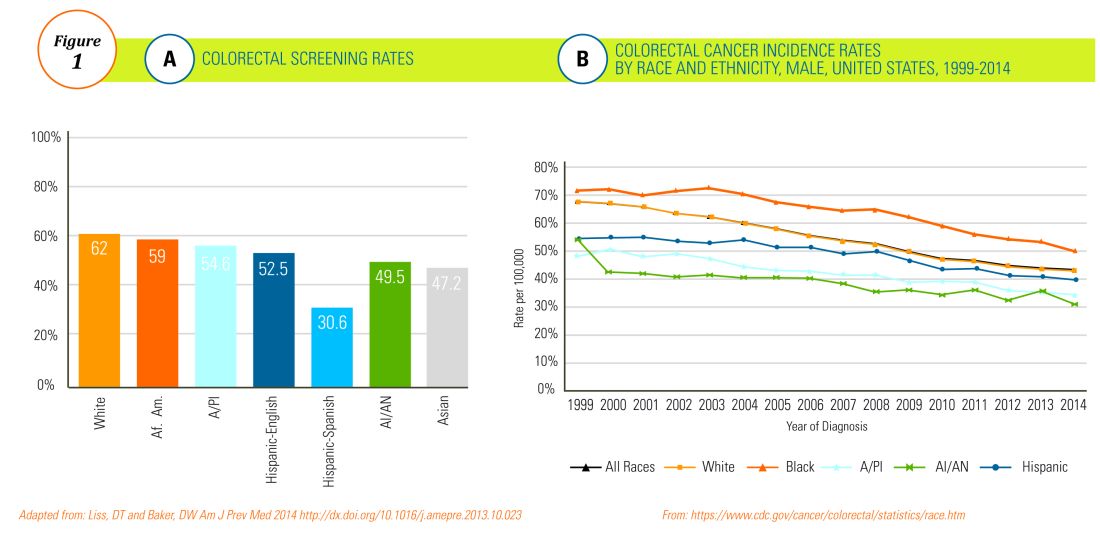

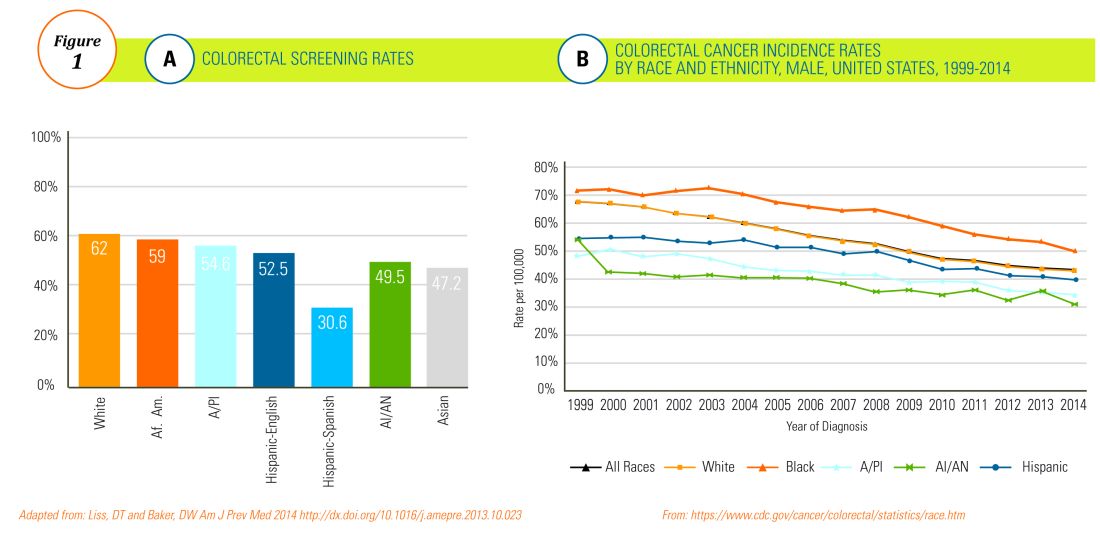

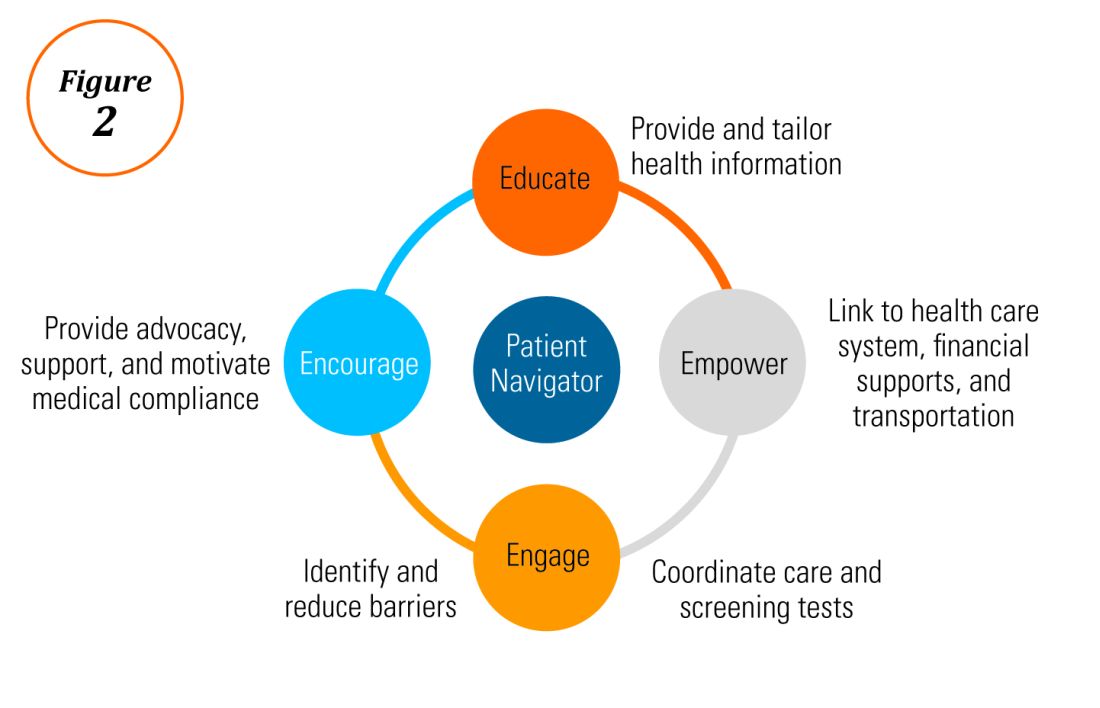

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32

Perceptions about CRC screening methods in Latino populations also have a tremendous influence and can include fear, stigma of sexual prejudice, embarrassment of being exposed during the exam, worries about humiliation in a male sense of masculinity, a lack of trust in the medical professionals, a sense of being a “guinea pig” for physicians, concerns about health care racism, and expectations of pain.33-37 Studies have reported that immigrants are afraid to seek health care because of the increasingly hostile environment associated with immigration enforcement.38 In addition, the impending dissolution of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act is likely to augment the barriers to care for Latino groups.39

In addition, provider-specific barriers to care also exist. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive recommendations for screening by their physician. In fact, this factor alone has been demonstrated to be the main reason for lack of screening among AAs in a Californian cohort.40 In addition, patients from rural areas or those from AI/AN communities are at especially increased risk for lack of access to care because of a scarcity of providers along with patient perceptions regarding their primary care provider’s ability to connect them to subspecialists.41-43 Other cited examples include misconceptions about and poor treatment of the LGBTQ population by health care providers/systems.44

How can we intervene successfully?

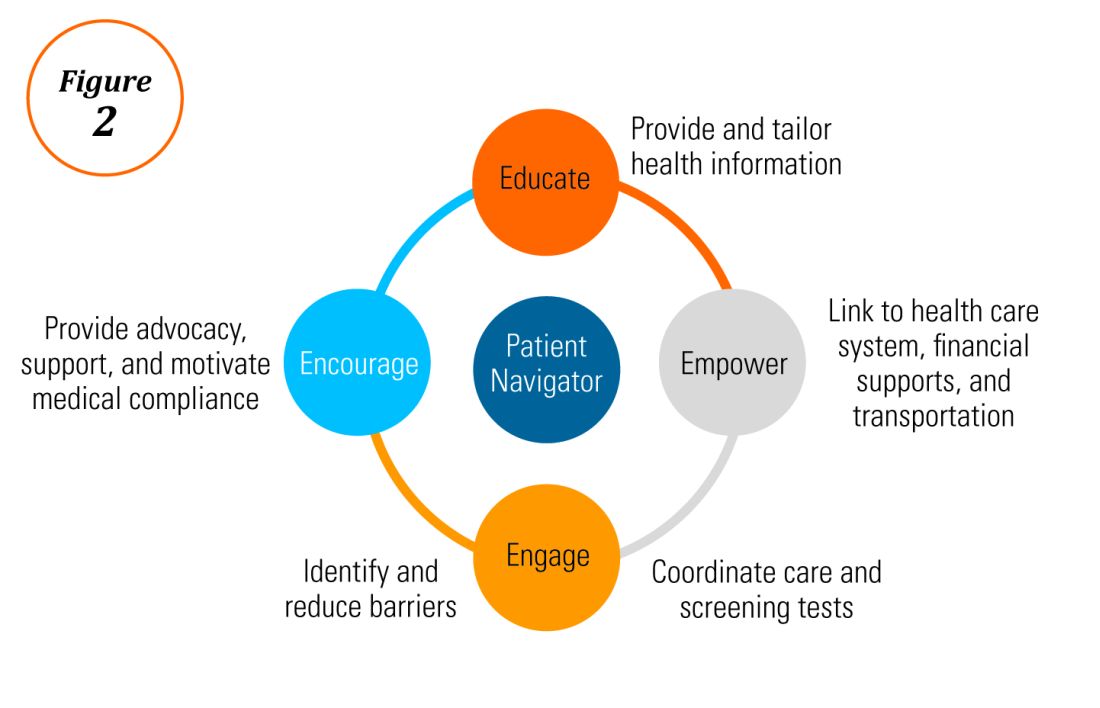

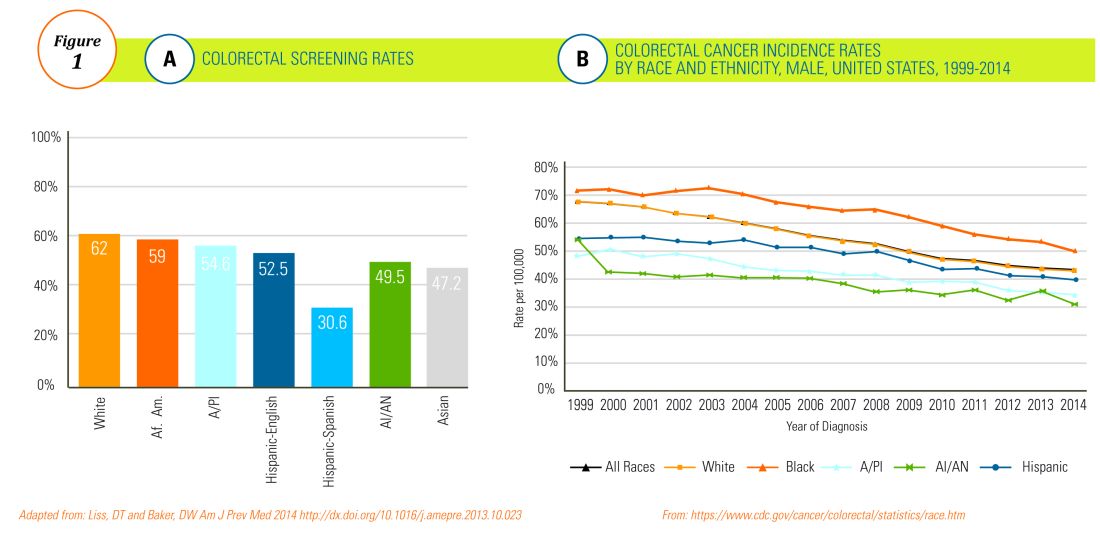

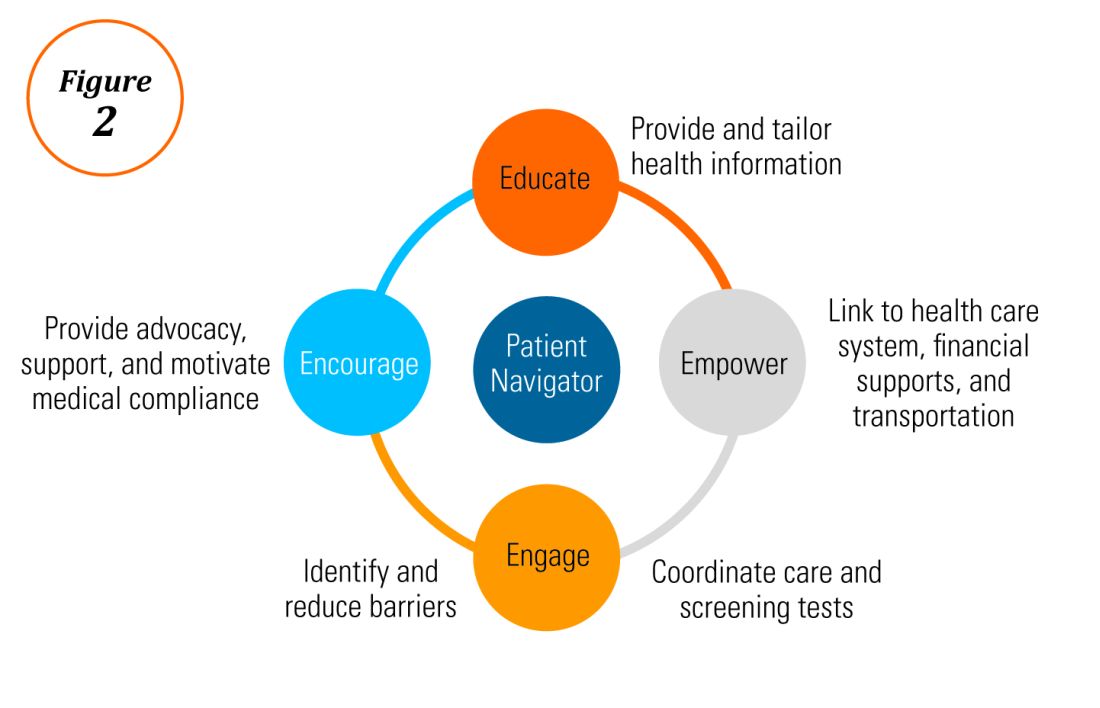

Characterization of barriers is important because it promotes the development of targeted interventions. Intervention models include community engagement programs, incorporation of fecal occult testing, and patient navigator programs.45-47 In response to the alarming disparity in CRC screening rates in Latino communities, several interventions have been set in motion in different clinical scenarios, which include patient navigation and a focus on patient education.

Randomized trials have shown that outreach efforts and patient navigation increase CRC screening rates in AAs.48,54,55 Studies evaluating the effects of print-based educational materials on improving screening showed improvement in screening rates, decreases in cancer-related fatalistic attitudes, and patients had a better understanding of the benefits of screening as compared with the cost associated with screening and the cost of advanced disease.56 Similarly, the use of touch-screen computers that tailor informational messages to decisional stage and screening barriers increased participation in CRC screening.57 Including patient navigators along with printed education material was even more effective at increasing the proportion of patients getting colonoscopy screening than providing printed material alone, with more-intensive navigation needed for individuals with low literacy.58 Grubbs et al.reported the success of their patient navigation program, which included wider comprehensive screening and coverage for colonoscopy screening.59 In AAs, they estimated an annual reduction of CRC incidence and mortality of 4,200 and 2,700 patients, respectively.

Among immigrants, there is an increased likelihood of CRC screening in those immigrants with a higher number of primary care visits.60 The intersection of culture, race, socioeconomic status, housing enclaves, limited English proficiency, low health literacy, and immigration policy all play a role in immigrant health and access to health care.61

Therefore, different strategies may be needed for each immigrant group to improve CRC screening. For this group of patients, efforts aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of national immigration policies on immigrant populations may have the additional consequence of improving health care access and CRC screening for these patients.

Data gaps still exist in our understanding of patient perceptions, perspectives, and barriers that present opportunities for further study to develop long-lasting interventions that will improve health care of underserved populations. By raising awareness of the barriers, physicians can enhance their own self-awareness to keenly be attuned to these challenges as patients cross their clinic threshold for medical care.

Additional resources link: www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/

References

1. Klabunde CN et al. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Aug;20(8):1611-21.

2. Parikh-Patel A et al. Colorectal cancer stage at diagnosis by socioeconomic and urban/rural status in California, 1988-2000. Cancer. 2006 Sep;107(5 Suppl):1189-95.

3. Promotion OoDPaH. Healthy People 2020. Cancer. Volume 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening – United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jan 27;61(3):41-5.

5. Doubeni CA et al. Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Feb;38(2):184-91.

6. Kupfer SS et al. Reducing colorectal cancer risk among African Americans. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov;149(6):1302-4.

7. Espey DK et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007 Nov;110(10):2119-52.

8. Day LW et al. Screening prevalence and incidence of colorectal cancer among American Indian/Alaskan natives in the Indian Health Service. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jul;56(7):2104-13.

9. Gupta S et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Apr;106(4):dju032.

10. Steele CB et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013 Nov 22;62(3):53-60.

11. Boehmer U et al. Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer 2011 Aug 15;117(16):3796-804.

12. Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Wei EK, et al. Application of the Rosner-Wei risk-prediction model to estimate sexual orientation patterns in colon cancer risk in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Aug;25(8):999-1006.

13. Heslin KC et al. Sexual orientation and testing for prostate and colorectal cancers among men in California. Med Care. 2008 Dec;46(12):1240-8.

14. McElroy JA et al. Advancing Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients in Missouri. Mo Med. 2015 Jul-Aug;112(4):262-5.

15. Greiner KA et al. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Nov;20(11):977-83.

16. Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004 May-Jun;27(3):206-15; quiz 216-7.

17. Berkowitz Z et al. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Feb;56(2):307-14.

18. Dolan NC et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jul;22(13):2617-22.

19. Peterson NB et al. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007 Oct;99(10):1105-12.

20. Haddock MG et al. Intraoperative irradiation for locally recurrent colorectal cancer in previously irradiated patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Apr 1;49(5):1267-74.

21. Jones RM et al. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010 May;38(5):508-16.

22. Basch CH et al. Screening colonoscopy bowel preparation: experience in an urban minority population. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;6(6):442-6.

23. Davis JL et al. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 Nov;23(4 Suppl):67-76.

24. Robinson CM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among publicly insured urban women: no knowledge of tests and no clinician recommendation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011 Aug;103(8):746-53.

25. Goldman RE et al. Perspectives of colorectal cancer risk and screening among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans: Stigma and misperceptions. Qual Health Res. 2009 Nov;19(11):1559-68.

26. Laiyemo AO et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: Health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Apr 21;102(8):538-46.

27. White A et al. Racial disparities and treatment trends in a large cohort of elderly African Americans and Caucasians with colorectal cancer, 1991 to 2002. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15;113(12):3400-9.

28. Doubeni CA et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population – A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36392.

29. Tammana VS, Laiyemo AO. Colorectal cancer disparities: Issues, controversies and solutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan 28;20(4):869-76.

30. Carethers JM. Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Mar;60(3):711-21.

31. Miranda-Diaz C et al. Barriers for Compliance to Breast, Colorectal, and Cervical Screening Cancer Tests among Hispanic Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Dec 22;13(1):ijerph13010021.

32. Sewali B et al. Understanding cancer screening service utilization by Somali men in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015 Jun;17(3):773-80.

33. Walsh JM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with non-Latino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):156-66.

34. Perez-Stable EJ et al. Self-reported use of cancer screening tests among Latinos and Anglos in a prepaid health plan. Arch Intern Med. 1994 May 23;154(10):1073-81.

35. Shariff-Marco S et al. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):364-74.

36. Powe BD et al. Comparing knowledge of colorectal and prostate cancer among African American and Hispanic men. Cancer Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;32(5):412-7.

37. Jun J, Oh KM. Asian and Hispanic Americans’ cancer fatalism and colon cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2013 Mar;37(2):145-54.

38. Hacker K et al. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: Perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Aug;73(4):586-94.

39. Firger J. Rescinding DACA could spur a public health crisis, from lost services to higher rates of depression, substance abuse. Newsweek.

40. May FP et al. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;110(10):1388-94.

41. Levy BT et al. Why hasn’t this patient been screened for colon cancer? An Iowa Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;20(5):458-68.

42. Rosenblatt RA. A view from the periphery – health care in rural America. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 9;351(11):1049-51.

43. Young WF et al. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural Colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J Rural Health. 2007 Summer;23(3):238-45.

44. Kates J et al. Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Individuals in the U.S. In: Foundation KF, ed. Disparities Policy Issue Brief. Volume 2017; Aug 30, 2017.

45. Katz ML et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007 Oct 1;110(7):1602-10.

46. Jean-Jacques M et al. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;10(5):412-7.

47. Reuland DS et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jul 1;177(7):967-74.

48. Percac-Lima S et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Feb;24(2):211-7.

49. Nash D et al. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006 Mar;83(2):231-43.

50. Lebwohl B et al. Effect of a patient navigator program on the volume and quality of colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 May-Jun;45(5):e47-53.

51. Khankari K et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: A pilot study within a federally qualified health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct;22(10):1410-4.

52. Wang JH et al. Recruiting Chinese Americans into cancer screening intervention trials: Strategies and outcomes. Clin Trials. 2014 Apr;11(2):167-77.

53. Katz ML et al. Patient activation increases colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized trial among low-income minority patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Jan;21(1):45-52.

54. Ford ME et al. Enhancing adherence among older African American men enrolled in a longitudinal cancer screening trial. Gerontologist. 2006 Aug;46(4):545-50.

55. Christie J et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008 Mar;100(3):278-84.

56. Philip EJ et al. Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: A preliminary study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010 Oct;21(10):1685-91.

57. Greiner KA et al. Implementation intentions and colorectal screening: A randomized trial in safety-net clinics. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):703-14.

58. Horne HN et al. Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2015 Feb;26(2):239-46.

59. Grubbs SS et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: It took a village. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 1;31(16):1928-30.

60. Jung MY et al. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb 25:1-20.

61. Viruell-Fuentes EA et al. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Dec;75(12):2099-106.

Dr. Oduyebo is a third-year fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Malespin is an assistant professor in the department of medicine and the medical director of hepatology at the University of Florida Health, Jacksonville; Dr. Mendoza Ladd is an assistant professor of medicine at Texas Tech University, El Paso; Dr. Day is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Charabaty is an associate professor of medicine and the director of the IBD Center in the division of gastroenterology at Medstar-Georgetown University Center, Washington; Dr. Chen is an associate professor of medicine, the director of patient safety and quality, and the director of the small-bowel endoscopy program in division of gastroenterology at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Carr is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Dr. Quezada is an assistant dean for admissions, an assistant dean for academic and multicultural affairs, and an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and Dr. Lamousé-Smith is a director of translational medicine, immunology, and early development at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Research and Development, Spring House, Penn.

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

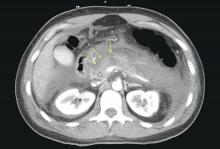

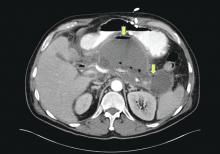

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32

Perceptions about CRC screening methods in Latino populations also have a tremendous influence and can include fear, stigma of sexual prejudice, embarrassment of being exposed during the exam, worries about humiliation in a male sense of masculinity, a lack of trust in the medical professionals, a sense of being a “guinea pig” for physicians, concerns about health care racism, and expectations of pain.33-37 Studies have reported that immigrants are afraid to seek health care because of the increasingly hostile environment associated with immigration enforcement.38 In addition, the impending dissolution of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act is likely to augment the barriers to care for Latino groups.39

In addition, provider-specific barriers to care also exist. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive recommendations for screening by their physician. In fact, this factor alone has been demonstrated to be the main reason for lack of screening among AAs in a Californian cohort.40 In addition, patients from rural areas or those from AI/AN communities are at especially increased risk for lack of access to care because of a scarcity of providers along with patient perceptions regarding their primary care provider’s ability to connect them to subspecialists.41-43 Other cited examples include misconceptions about and poor treatment of the LGBTQ population by health care providers/systems.44

How can we intervene successfully?

Characterization of barriers is important because it promotes the development of targeted interventions. Intervention models include community engagement programs, incorporation of fecal occult testing, and patient navigator programs.45-47 In response to the alarming disparity in CRC screening rates in Latino communities, several interventions have been set in motion in different clinical scenarios, which include patient navigation and a focus on patient education.

Randomized trials have shown that outreach efforts and patient navigation increase CRC screening rates in AAs.48,54,55 Studies evaluating the effects of print-based educational materials on improving screening showed improvement in screening rates, decreases in cancer-related fatalistic attitudes, and patients had a better understanding of the benefits of screening as compared with the cost associated with screening and the cost of advanced disease.56 Similarly, the use of touch-screen computers that tailor informational messages to decisional stage and screening barriers increased participation in CRC screening.57 Including patient navigators along with printed education material was even more effective at increasing the proportion of patients getting colonoscopy screening than providing printed material alone, with more-intensive navigation needed for individuals with low literacy.58 Grubbs et al.reported the success of their patient navigation program, which included wider comprehensive screening and coverage for colonoscopy screening.59 In AAs, they estimated an annual reduction of CRC incidence and mortality of 4,200 and 2,700 patients, respectively.

Among immigrants, there is an increased likelihood of CRC screening in those immigrants with a higher number of primary care visits.60 The intersection of culture, race, socioeconomic status, housing enclaves, limited English proficiency, low health literacy, and immigration policy all play a role in immigrant health and access to health care.61

Therefore, different strategies may be needed for each immigrant group to improve CRC screening. For this group of patients, efforts aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of national immigration policies on immigrant populations may have the additional consequence of improving health care access and CRC screening for these patients.

Data gaps still exist in our understanding of patient perceptions, perspectives, and barriers that present opportunities for further study to develop long-lasting interventions that will improve health care of underserved populations. By raising awareness of the barriers, physicians can enhance their own self-awareness to keenly be attuned to these challenges as patients cross their clinic threshold for medical care.

Additional resources link: www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/

References

1. Klabunde CN et al. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Aug;20(8):1611-21.

2. Parikh-Patel A et al. Colorectal cancer stage at diagnosis by socioeconomic and urban/rural status in California, 1988-2000. Cancer. 2006 Sep;107(5 Suppl):1189-95.

3. Promotion OoDPaH. Healthy People 2020. Cancer. Volume 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening – United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jan 27;61(3):41-5.

5. Doubeni CA et al. Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Feb;38(2):184-91.

6. Kupfer SS et al. Reducing colorectal cancer risk among African Americans. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov;149(6):1302-4.

7. Espey DK et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007 Nov;110(10):2119-52.

8. Day LW et al. Screening prevalence and incidence of colorectal cancer among American Indian/Alaskan natives in the Indian Health Service. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jul;56(7):2104-13.

9. Gupta S et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Apr;106(4):dju032.

10. Steele CB et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013 Nov 22;62(3):53-60.

11. Boehmer U et al. Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer 2011 Aug 15;117(16):3796-804.

12. Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Wei EK, et al. Application of the Rosner-Wei risk-prediction model to estimate sexual orientation patterns in colon cancer risk in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Aug;25(8):999-1006.

13. Heslin KC et al. Sexual orientation and testing for prostate and colorectal cancers among men in California. Med Care. 2008 Dec;46(12):1240-8.

14. McElroy JA et al. Advancing Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients in Missouri. Mo Med. 2015 Jul-Aug;112(4):262-5.

15. Greiner KA et al. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Nov;20(11):977-83.

16. Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004 May-Jun;27(3):206-15; quiz 216-7.

17. Berkowitz Z et al. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Feb;56(2):307-14.

18. Dolan NC et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jul;22(13):2617-22.

19. Peterson NB et al. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007 Oct;99(10):1105-12.

20. Haddock MG et al. Intraoperative irradiation for locally recurrent colorectal cancer in previously irradiated patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Apr 1;49(5):1267-74.

21. Jones RM et al. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010 May;38(5):508-16.

22. Basch CH et al. Screening colonoscopy bowel preparation: experience in an urban minority population. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;6(6):442-6.

23. Davis JL et al. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 Nov;23(4 Suppl):67-76.

24. Robinson CM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among publicly insured urban women: no knowledge of tests and no clinician recommendation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011 Aug;103(8):746-53.

25. Goldman RE et al. Perspectives of colorectal cancer risk and screening among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans: Stigma and misperceptions. Qual Health Res. 2009 Nov;19(11):1559-68.

26. Laiyemo AO et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: Health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Apr 21;102(8):538-46.

27. White A et al. Racial disparities and treatment trends in a large cohort of elderly African Americans and Caucasians with colorectal cancer, 1991 to 2002. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15;113(12):3400-9.

28. Doubeni CA et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population – A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36392.

29. Tammana VS, Laiyemo AO. Colorectal cancer disparities: Issues, controversies and solutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan 28;20(4):869-76.

30. Carethers JM. Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Mar;60(3):711-21.

31. Miranda-Diaz C et al. Barriers for Compliance to Breast, Colorectal, and Cervical Screening Cancer Tests among Hispanic Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Dec 22;13(1):ijerph13010021.

32. Sewali B et al. Understanding cancer screening service utilization by Somali men in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015 Jun;17(3):773-80.

33. Walsh JM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with non-Latino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):156-66.

34. Perez-Stable EJ et al. Self-reported use of cancer screening tests among Latinos and Anglos in a prepaid health plan. Arch Intern Med. 1994 May 23;154(10):1073-81.

35. Shariff-Marco S et al. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):364-74.

36. Powe BD et al. Comparing knowledge of colorectal and prostate cancer among African American and Hispanic men. Cancer Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;32(5):412-7.

37. Jun J, Oh KM. Asian and Hispanic Americans’ cancer fatalism and colon cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2013 Mar;37(2):145-54.

38. Hacker K et al. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: Perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Aug;73(4):586-94.

39. Firger J. Rescinding DACA could spur a public health crisis, from lost services to higher rates of depression, substance abuse. Newsweek.

40. May FP et al. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;110(10):1388-94.

41. Levy BT et al. Why hasn’t this patient been screened for colon cancer? An Iowa Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;20(5):458-68.

42. Rosenblatt RA. A view from the periphery – health care in rural America. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 9;351(11):1049-51.

43. Young WF et al. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural Colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J Rural Health. 2007 Summer;23(3):238-45.

44. Kates J et al. Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Individuals in the U.S. In: Foundation KF, ed. Disparities Policy Issue Brief. Volume 2017; Aug 30, 2017.

45. Katz ML et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007 Oct 1;110(7):1602-10.

46. Jean-Jacques M et al. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;10(5):412-7.

47. Reuland DS et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jul 1;177(7):967-74.

48. Percac-Lima S et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Feb;24(2):211-7.

49. Nash D et al. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006 Mar;83(2):231-43.

50. Lebwohl B et al. Effect of a patient navigator program on the volume and quality of colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 May-Jun;45(5):e47-53.

51. Khankari K et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: A pilot study within a federally qualified health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct;22(10):1410-4.

52. Wang JH et al. Recruiting Chinese Americans into cancer screening intervention trials: Strategies and outcomes. Clin Trials. 2014 Apr;11(2):167-77.

53. Katz ML et al. Patient activation increases colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized trial among low-income minority patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Jan;21(1):45-52.

54. Ford ME et al. Enhancing adherence among older African American men enrolled in a longitudinal cancer screening trial. Gerontologist. 2006 Aug;46(4):545-50.

55. Christie J et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008 Mar;100(3):278-84.

56. Philip EJ et al. Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: A preliminary study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010 Oct;21(10):1685-91.

57. Greiner KA et al. Implementation intentions and colorectal screening: A randomized trial in safety-net clinics. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):703-14.

58. Horne HN et al. Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2015 Feb;26(2):239-46.

59. Grubbs SS et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: It took a village. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 1;31(16):1928-30.

60. Jung MY et al. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb 25:1-20.

61. Viruell-Fuentes EA et al. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Dec;75(12):2099-106.

Dr. Oduyebo is a third-year fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Malespin is an assistant professor in the department of medicine and the medical director of hepatology at the University of Florida Health, Jacksonville; Dr. Mendoza Ladd is an assistant professor of medicine at Texas Tech University, El Paso; Dr. Day is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Charabaty is an associate professor of medicine and the director of the IBD Center in the division of gastroenterology at Medstar-Georgetown University Center, Washington; Dr. Chen is an associate professor of medicine, the director of patient safety and quality, and the director of the small-bowel endoscopy program in division of gastroenterology at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Carr is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Dr. Quezada is an assistant dean for admissions, an assistant dean for academic and multicultural affairs, and an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and Dr. Lamousé-Smith is a director of translational medicine, immunology, and early development at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Research and Development, Spring House, Penn.

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32

Perceptions about CRC screening methods in Latino populations also have a tremendous influence and can include fear, stigma of sexual prejudice, embarrassment of being exposed during the exam, worries about humiliation in a male sense of masculinity, a lack of trust in the medical professionals, a sense of being a “guinea pig” for physicians, concerns about health care racism, and expectations of pain.33-37 Studies have reported that immigrants are afraid to seek health care because of the increasingly hostile environment associated with immigration enforcement.38 In addition, the impending dissolution of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act is likely to augment the barriers to care for Latino groups.39

In addition, provider-specific barriers to care also exist. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive recommendations for screening by their physician. In fact, this factor alone has been demonstrated to be the main reason for lack of screening among AAs in a Californian cohort.40 In addition, patients from rural areas or those from AI/AN communities are at especially increased risk for lack of access to care because of a scarcity of providers along with patient perceptions regarding their primary care provider’s ability to connect them to subspecialists.41-43 Other cited examples include misconceptions about and poor treatment of the LGBTQ population by health care providers/systems.44

How can we intervene successfully?

Characterization of barriers is important because it promotes the development of targeted interventions. Intervention models include community engagement programs, incorporation of fecal occult testing, and patient navigator programs.45-47 In response to the alarming disparity in CRC screening rates in Latino communities, several interventions have been set in motion in different clinical scenarios, which include patient navigation and a focus on patient education.

Randomized trials have shown that outreach efforts and patient navigation increase CRC screening rates in AAs.48,54,55 Studies evaluating the effects of print-based educational materials on improving screening showed improvement in screening rates, decreases in cancer-related fatalistic attitudes, and patients had a better understanding of the benefits of screening as compared with the cost associated with screening and the cost of advanced disease.56 Similarly, the use of touch-screen computers that tailor informational messages to decisional stage and screening barriers increased participation in CRC screening.57 Including patient navigators along with printed education material was even more effective at increasing the proportion of patients getting colonoscopy screening than providing printed material alone, with more-intensive navigation needed for individuals with low literacy.58 Grubbs et al.reported the success of their patient navigation program, which included wider comprehensive screening and coverage for colonoscopy screening.59 In AAs, they estimated an annual reduction of CRC incidence and mortality of 4,200 and 2,700 patients, respectively.

Among immigrants, there is an increased likelihood of CRC screening in those immigrants with a higher number of primary care visits.60 The intersection of culture, race, socioeconomic status, housing enclaves, limited English proficiency, low health literacy, and immigration policy all play a role in immigrant health and access to health care.61

Therefore, different strategies may be needed for each immigrant group to improve CRC screening. For this group of patients, efforts aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of national immigration policies on immigrant populations may have the additional consequence of improving health care access and CRC screening for these patients.

Data gaps still exist in our understanding of patient perceptions, perspectives, and barriers that present opportunities for further study to develop long-lasting interventions that will improve health care of underserved populations. By raising awareness of the barriers, physicians can enhance their own self-awareness to keenly be attuned to these challenges as patients cross their clinic threshold for medical care.

Additional resources link: www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/

References

1. Klabunde CN et al. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Aug;20(8):1611-21.

2. Parikh-Patel A et al. Colorectal cancer stage at diagnosis by socioeconomic and urban/rural status in California, 1988-2000. Cancer. 2006 Sep;107(5 Suppl):1189-95.

3. Promotion OoDPaH. Healthy People 2020. Cancer. Volume 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening – United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jan 27;61(3):41-5.

5. Doubeni CA et al. Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Feb;38(2):184-91.

6. Kupfer SS et al. Reducing colorectal cancer risk among African Americans. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov;149(6):1302-4.

7. Espey DK et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007 Nov;110(10):2119-52.

8. Day LW et al. Screening prevalence and incidence of colorectal cancer among American Indian/Alaskan natives in the Indian Health Service. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jul;56(7):2104-13.

9. Gupta S et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Apr;106(4):dju032.

10. Steele CB et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013 Nov 22;62(3):53-60.

11. Boehmer U et al. Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer 2011 Aug 15;117(16):3796-804.

12. Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Wei EK, et al. Application of the Rosner-Wei risk-prediction model to estimate sexual orientation patterns in colon cancer risk in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Aug;25(8):999-1006.

13. Heslin KC et al. Sexual orientation and testing for prostate and colorectal cancers among men in California. Med Care. 2008 Dec;46(12):1240-8.

14. McElroy JA et al. Advancing Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients in Missouri. Mo Med. 2015 Jul-Aug;112(4):262-5.

15. Greiner KA et al. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Nov;20(11):977-83.

16. Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004 May-Jun;27(3):206-15; quiz 216-7.

17. Berkowitz Z et al. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Feb;56(2):307-14.

18. Dolan NC et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jul;22(13):2617-22.

19. Peterson NB et al. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007 Oct;99(10):1105-12.

20. Haddock MG et al. Intraoperative irradiation for locally recurrent colorectal cancer in previously irradiated patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Apr 1;49(5):1267-74.

21. Jones RM et al. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010 May;38(5):508-16.

22. Basch CH et al. Screening colonoscopy bowel preparation: experience in an urban minority population. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;6(6):442-6.

23. Davis JL et al. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 Nov;23(4 Suppl):67-76.

24. Robinson CM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among publicly insured urban women: no knowledge of tests and no clinician recommendation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011 Aug;103(8):746-53.

25. Goldman RE et al. Perspectives of colorectal cancer risk and screening among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans: Stigma and misperceptions. Qual Health Res. 2009 Nov;19(11):1559-68.

26. Laiyemo AO et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: Health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Apr 21;102(8):538-46.

27. White A et al. Racial disparities and treatment trends in a large cohort of elderly African Americans and Caucasians with colorectal cancer, 1991 to 2002. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15;113(12):3400-9.

28. Doubeni CA et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population – A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36392.

29. Tammana VS, Laiyemo AO. Colorectal cancer disparities: Issues, controversies and solutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan 28;20(4):869-76.

30. Carethers JM. Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Mar;60(3):711-21.

31. Miranda-Diaz C et al. Barriers for Compliance to Breast, Colorectal, and Cervical Screening Cancer Tests among Hispanic Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Dec 22;13(1):ijerph13010021.

32. Sewali B et al. Understanding cancer screening service utilization by Somali men in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015 Jun;17(3):773-80.

33. Walsh JM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with non-Latino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):156-66.

34. Perez-Stable EJ et al. Self-reported use of cancer screening tests among Latinos and Anglos in a prepaid health plan. Arch Intern Med. 1994 May 23;154(10):1073-81.

35. Shariff-Marco S et al. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):364-74.

36. Powe BD et al. Comparing knowledge of colorectal and prostate cancer among African American and Hispanic men. Cancer Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;32(5):412-7.

37. Jun J, Oh KM. Asian and Hispanic Americans’ cancer fatalism and colon cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2013 Mar;37(2):145-54.

38. Hacker K et al. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: Perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Aug;73(4):586-94.

39. Firger J. Rescinding DACA could spur a public health crisis, from lost services to higher rates of depression, substance abuse. Newsweek.

40. May FP et al. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;110(10):1388-94.

41. Levy BT et al. Why hasn’t this patient been screened for colon cancer? An Iowa Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;20(5):458-68.

42. Rosenblatt RA. A view from the periphery – health care in rural America. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 9;351(11):1049-51.

43. Young WF et al. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural Colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J Rural Health. 2007 Summer;23(3):238-45.

44. Kates J et al. Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Individuals in the U.S. In: Foundation KF, ed. Disparities Policy Issue Brief. Volume 2017; Aug 30, 2017.

45. Katz ML et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007 Oct 1;110(7):1602-10.

46. Jean-Jacques M et al. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;10(5):412-7.

47. Reuland DS et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jul 1;177(7):967-74.

48. Percac-Lima S et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Feb;24(2):211-7.

49. Nash D et al. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006 Mar;83(2):231-43.

50. Lebwohl B et al. Effect of a patient navigator program on the volume and quality of colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 May-Jun;45(5):e47-53.

51. Khankari K et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: A pilot study within a federally qualified health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct;22(10):1410-4.

52. Wang JH et al. Recruiting Chinese Americans into cancer screening intervention trials: Strategies and outcomes. Clin Trials. 2014 Apr;11(2):167-77.

53. Katz ML et al. Patient activation increases colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized trial among low-income minority patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Jan;21(1):45-52.

54. Ford ME et al. Enhancing adherence among older African American men enrolled in a longitudinal cancer screening trial. Gerontologist. 2006 Aug;46(4):545-50.

55. Christie J et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008 Mar;100(3):278-84.

56. Philip EJ et al. Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: A preliminary study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010 Oct;21(10):1685-91.

57. Greiner KA et al. Implementation intentions and colorectal screening: A randomized trial in safety-net clinics. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):703-14.

58. Horne HN et al. Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2015 Feb;26(2):239-46.

59. Grubbs SS et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: It took a village. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 1;31(16):1928-30.

60. Jung MY et al. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb 25:1-20.

61. Viruell-Fuentes EA et al. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Dec;75(12):2099-106.

Dr. Oduyebo is a third-year fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Malespin is an assistant professor in the department of medicine and the medical director of hepatology at the University of Florida Health, Jacksonville; Dr. Mendoza Ladd is an assistant professor of medicine at Texas Tech University, El Paso; Dr. Day is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Charabaty is an associate professor of medicine and the director of the IBD Center in the division of gastroenterology at Medstar-Georgetown University Center, Washington; Dr. Chen is an associate professor of medicine, the director of patient safety and quality, and the director of the small-bowel endoscopy program in division of gastroenterology at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Carr is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Dr. Quezada is an assistant dean for admissions, an assistant dean for academic and multicultural affairs, and an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and Dr. Lamousé-Smith is a director of translational medicine, immunology, and early development at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Research and Development, Spring House, Penn.

Chronic constipation: Practical approaches and novel therapies

While constipation is one of the most common symptoms managed by practicing gastroenterologists, it can also be among the most challenging. As a presenting complaint, constipation manifests with widely varying degrees of severity and may be seen in all age groups, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Its implications can include chronic and serious functional impairment as well as protracted and often excessive health care utilization. A growing number of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have become available and proven to be effective when appropriately deployed. As such, health care providers and particularly gastroenterologists should strive to develop logical and efficient strategies for addressing this common disorder.

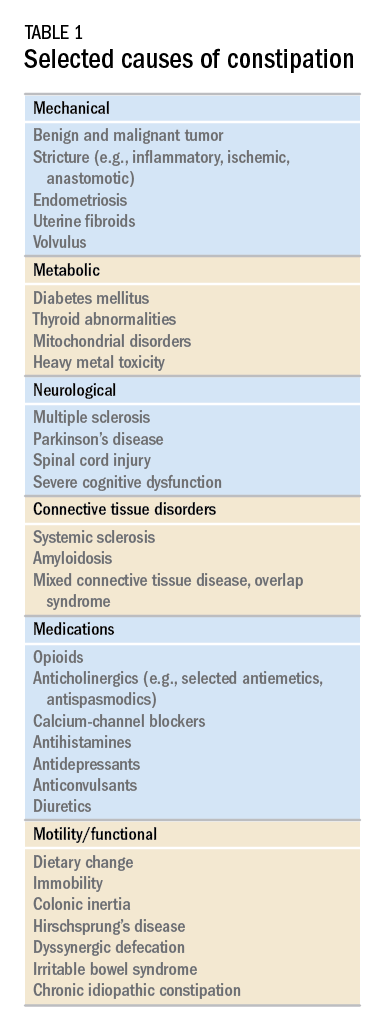

Clinical importance

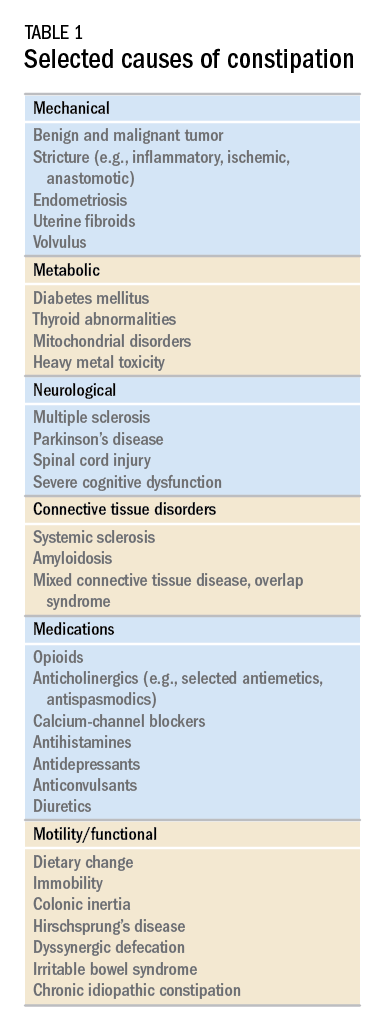

While there are a variety of etiologies for constipation (Table 1), a large proportion of chronic cases fall within the framework of functional gastrointestinal disorders, a category with a substantial burden of disease across the population. Prevalence estimates vary, but constipation likely affects between 12% and 20% of the North American population.1 Research has demonstrated significant health care expenditures associated with chronic constipation management; U.S. estimates suggest direct costs on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars per year, roughly half of which are attributable to inpatient care.2 The financial burden of constipation also includes indirect costs associated with absenteeism as well as the risks of hospitalization and invasive procedures.3

Physical and emotional complications can be likewise significant and affect all age groups, from newborns to patients in the last days of life. Hirschsprung’s disease, for example, can lead to life-threatening sequelae in infancy, such as spontaneous perforation or enterocolitis, or more prolonged functional impairments when it remains undiagnosed. Severe constipation in childhood can lead to encopresis, translating in turn into ostracism and impaired social functioning. Fecal incontinence associated with overflow diarrhea is common and debilitating, particularly in the elderly population.

The potential mechanical complications of constipation lead to its overlap with a variety of other gastrointestinal complaints. For example, the difficulties of passing inspissated stool can provoke lower gastrointestinal bleeding from irritated hemorrhoids, anal fissures, stercoral ulcers, or prolapsed rectal tissue. Retained stool can also lead to upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as postprandial bloating or early satiety.4 Delayed fecal discharge can promote an increase in fermentative microbiota, associated in turn with the production of short-chain fatty acids, methane, and other gaseous byproducts.

The initial assessment

History

Taking an appropriate history is an essential step toward achieving a successful outcome. Presenting concerns related to constipation can range from hard, infrequent, or small-volume stools; abdominal or rectal pain associated with the process of elimination; and bloating, nausea, or early satiety. A sound diagnosis requires a keen understanding of what patients mean when they indicate that they are constipated, an accurate assessment of its impact on quality of life, and a careful inventory of potentially associated complications.

It is critical to define the duration of the problem. Not infrequently, patients will focus on recent events while failing to reveal that altered bowel habits or other functional symptoms have been problematic for years. Reminding the patients to “begin at the beginning” can aid enormously in contextualizing their complaints. Individuals with longstanding symptoms and previously negative evaluations are much less likely to present with a new organic disease than are those in whom symptoms have truly arisen de novo.

Defining constipation by frequency of bowel eliminations alone has proved inaccurate at predicting actual severity. This is in part because the bowel movement frequency varies widely in healthy individuals (anywhere from thrice daily to once every 3 days) and in part because the primary indicator of effective evacuation is not frequency but volume – a much more difficult quantity for patients to gauge.5 The Bristol Stool Scale is a simple, standardized tool that more accurately evaluates the presence or absence of colonic dysfunction. For example, patients passing Type 1-2 (hard or lumpy) stools often have an element of constipation that needs to be addressed.6 However, the interpretation of stool consistency assessments is still aided by awareness of both frequency and volume. A patient passing multiple small-volume Type 6-7 (loose or watery) stools may be the most constipated, presenting with overflow or paradoxical diarrhea attributable to fecal impaction.

Physical examination

An expert physical exam is another essential aspect of the initial assessment. Alarm features can be elicited in this context as well via signs of pallor, weight loss, blood in the stool, physical abuse, or advanced psychological distress. Attention should also be paid to signs of a systemic disorder that might be associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility including previously unrecognized signs of Raynaud’s syndrome, sclerodactyly, amyloidosis, surgical scars, and joint hypermobility.7,8 Abdominal bloating, a frequently vague symptomatic complaint, can be correlated with the presence or absence of distention as perceived by the patient and/or the examiner.9

Any initial evaluation of constipation should also include a detailed digital rectal exam. A complete examination should include a careful visual assessment of the perianal region for external lesions and of the degree and directional appropriateness of pelvic floor excursion (perineal elevation and descent) during squeeze and simulated defecation maneuvers, respectively. Digital examination should include palpation for the presence or absence of pain as well as stool, blood, or masses in the rectal vault, as well as an assessment of sphincter tone at baseline, with squeeze, and with simulated defecation. Rectal pressure generation with the latter maneuver can also be qualitatively assessed. Research has suggested moderate agreement between the digital rectal examination and formal manometric evaluation in diagnosing dyssynergic defecation, underscoring the former’s utility in guiding initial management decisions.10

Testing

It is reasonable to exclude metabolic, inflammatory, or other secondary etiologies of constipation in patients in whom history or examination raises suspicion. Likewise, colonoscopy should be considered in patients with alarm features or who are due for age-appropriate screening. That said, in the absence of risk factors or ancillary signs and symptoms, a detailed diagnostic work-up is often unnecessary. The AGA’s Medical Position Statement on Constipation recommends a complete blood count as the only test to be ordered on a standard basis in the work-up of constipation.11

In patients new to one’s practice, the diligent retrieval of prior records is one of the most efficient ways to avoid wasting health care resources. Locating an old abdominal radiograph that demonstrates extensive retained stool can not only secure the diagnosis for vague symptomatic complaints but also obviate the need for more extensive testing. One should instead consider how symptom duration and the associated changes in objectives measures such as weight and laboratory parameters can be used to justify or refute the need for repeating costly or invasive studies.

It is important to consider the potential contribution of defecatory dyssynergy to chronic constipation early in a patient’s presentation, and to return to this possibility in the future if initial therapeutic interventions are unsuccessful. An abnormal qualitative assessment on digital rectal examination should trigger a more formal characterization of the patient’s defecatory mechanics via anorectal manometry (ARM) and balloon expulsion testing (BET). Likewise, a lack of response to initial pharmacotherapy should prompt suspicion for outlet dysfunction, which can be queried with functional testing even if a rectal examination is qualitatively unrevealing.

Initial approach to the chronically constipated patient

The aforementioned AGA Medical Position Statement provides a helpful algorithm regarding the diagnostic approach to constipation (Figure 1). In the absence of concern for secondary etiologies of constipation, an initial therapeutic trial of dietary, lifestyle, and medication-based intervention is reasonable for mild symptoms. Patients should be encouraged to strive for 25-30 grams of dietary fiber intake per day. For patients unable to reach this goal via high-fiber foods alone, psyllium husk is a popular supplement, but it should be initiated at modest doses to mitigate the risk of bloating. Fiber may be supplemented with the use of osmotic laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol) with instructions that the initial dose may be modified as needed to optimal effectiveness. Selective response to rectal therapies (e.g., bisacodyl or glycerin suppositories) over osmotic laxatives may also suggest utility in early queries of outlet dysfunction.

An abdominal radiograph can be helpful not only to diagnose constipation but also to assess the stool burden present at the time of beginning treatment. For patients presenting with a significant degree of fecal loading, an initial bowel cleanse with four liters of osmotically balanced polyethylene glycol can be a useful means of eliminating background fecal impactions that might have mitigated the effectiveness of initial therapies in the past or that might reduce the effectiveness of daily laxative therapy moving forward.

Patients with a diagnosis of defecatory dyssynergy made via ARM/BET should be referred to pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback. Recognizing that courses of therapy are highly individualized in practice, randomized controlled trials suggest symptom improvement in 70%-80% of patients, with the majority also demonstrating maintenance of response.12 Biofeedback appears to be an essential component of this modality based on meta-analysis data and should be requested specifically by the referring provider.13

Pharmacologic agents