User login

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

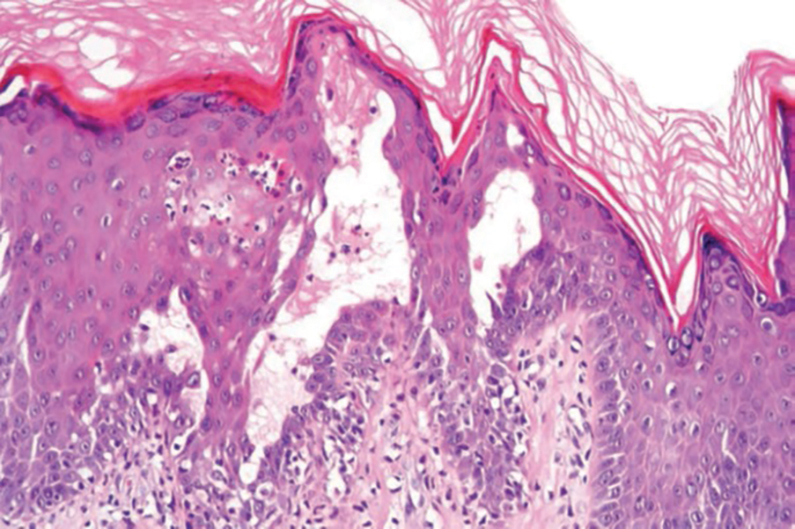

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Solitary Lesion on the Umbilicus

Solitary Lesion on the Umbilicus

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the ectopic presence of endometrial tissue and occurs in approximately 13% of women of childbearing age.1 This non-neoplastic lesion can manifest on the skin in less than 5.5% of endometriosis cases worldwide. Historically, secondary cutaneous endometriosis (CE) most frequently has been associated with prior gynecologic surgery (often cesarean section)2; however, an increased incidence of primary CE in patients without prior surgical history recently has been documented in the literature.3 While secondary CE usually manifests at the site of a surgical scar, primary CE has a predilection for the umbilicus (Villar nodule). In both primary and secondary CE, patients present clinically with a solitary nodule and abdominal pain that may be exacerbated during menstruation. Bleeding without associated pain may be more common in primary CE, while bleeding with pain may be more common in secondary CE. Cutaneous endometriosis often is overlooked given its low incidence, leading to delayed diagnosis. Primary CE often is misdiagnosed clinically as a pyogenic granuloma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, or keloid, while secondary CE may be mistaken for a fibroma, incisional hernia, or granuloma.2

Primary and secondary CE have identical histopathologic features. Glands of variable size consisting of a single epithelial layer of columnar cells are present in the reticular dermis or subcutis (quiz image).4 The accompanying periglandular stroma often is uniform, consisting of spindle-shaped basophilic cells with abundant vascular structures. The stroma may contain moderate numbers of mitotic figures, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and extravasated red blood cells. The ectopic tissue may be inactive or display morphologic changes resembling those of the endometrium in the normal menstrual cycle.4 As the ectopic tissue progresses through the stages of menstruation, the glandular morphology also transforms. The proliferative stage demonstrates increased epithelial mitotic figures, the secretory stage exhibits intraluminal secretion, and during menstruation there are degenerative epithelial cells and evidence of vascular congestion. A mixture of glandular stages may be seen in biopsy results. Robust immunohistochemical expression of CD10 in the endometrial stroma can aid in diagnosis (Figure 1). Estrogen and progesterone receptor immunostaining also shows strong nuclear positivity, except in decidualized tissue.4 Unlike intestinal glands, endometrial glands do not express CDX2 or CK20.5 Complete surgical excision of CE usually is curative; however, recurrence has been documented in 10% (3/30) of cases.2

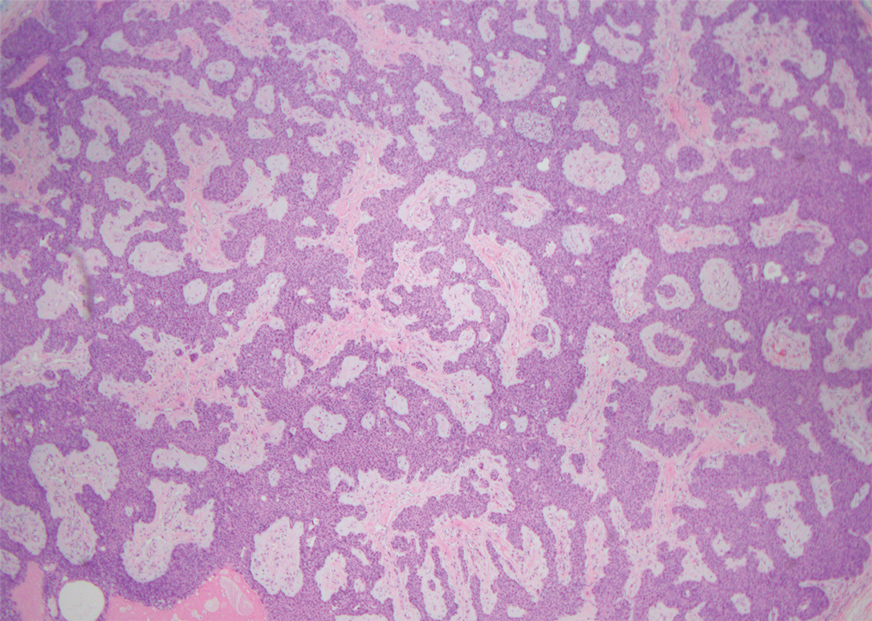

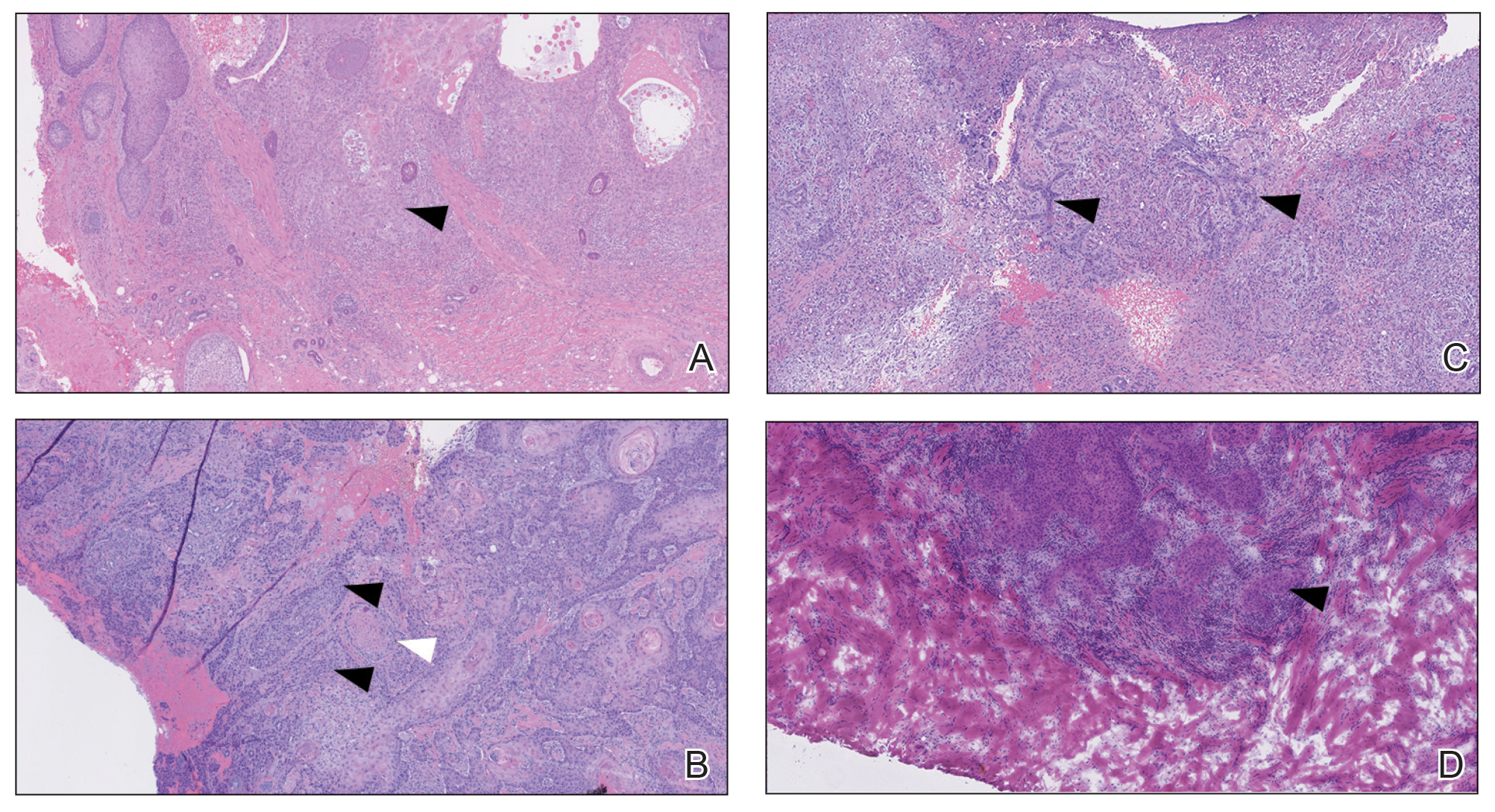

Breast carcinoma is the most common internal malignancy associated with cutaneous metastasis and may develop prior to visceral diagnosis. It is possible that tumor cells travel through the communicating networks of the cutaneous lymphatic ducts and the mammary lymphatic plexus; however, cutaneous manifestation often is located on the ipsilateral breast, and therefore tumor expansion rather than true metastasis cannot always be ruled out. On histopathology, findings of breast adenocarcinoma include tumor cells that tend to show either interstitial, nodular, mixed, or intravascular growth patterns (Figure 2). Tumor cells may invade the stroma in clusters or as individual cells. Sites of distant metastasis may show an increased likelihood of vascular and lymphatic invasion.6

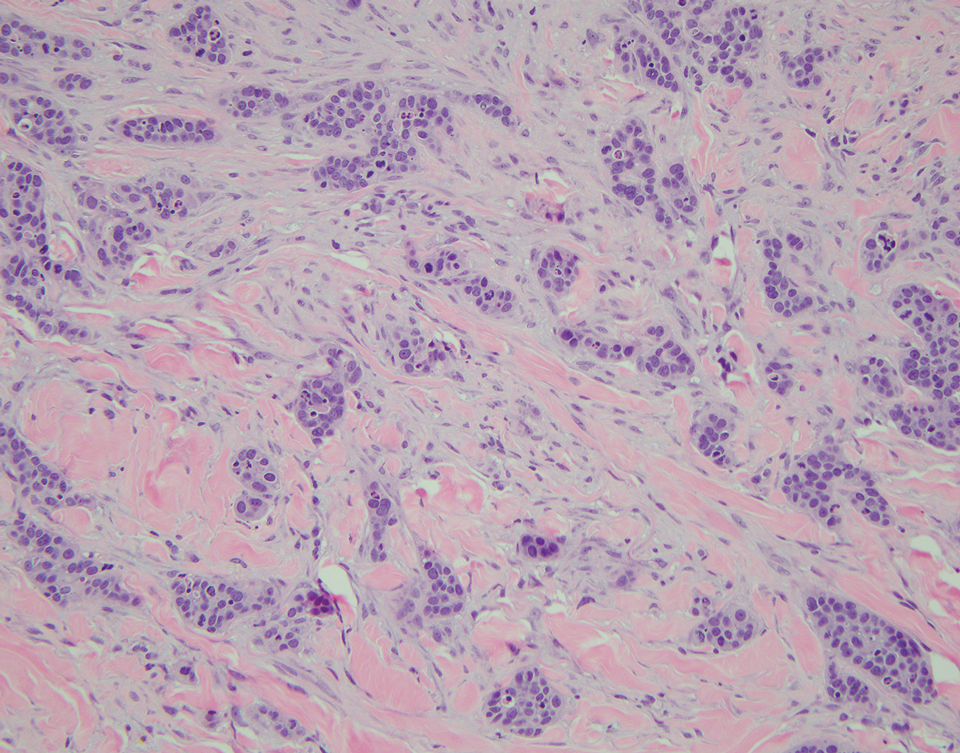

Nodular hidradenoma often manifests as a solitary nodule in the head or neck region, predominantly in women.7 Pathology shows well-demarcated intradermal aggregates of tumor cells within a hyalinized stroma; connection to the epidermis is not a feature of nodular hidradenoma. The epithelial component consists of polygonal cells with eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm as well as large glycogenated cells with pale to clear cytoplasm (leading to the alternative term clear cell hidradenoma)(Figure 3). The cystic portion represents deterioration of tumor cells. Surgical excision usually is curative, although lesions may recur. Malignant transformation is rare.7

Sister Mary Joseph nodule is a cutaneous involvement of the umbilicus by a metastatic malignancy, often from an intra-abdominal primary malignancy (most commonly ovarian carcinoma in women and colonic carcinoma in men). Clinically, patients present with a solitary firm nodule or plaque within the umbilicus.8,9 Histopathology recapitulates the primary tumor (Figure 4).9 Sister Mary Joseph nodule portends a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of less than 8 months from the time of diagnosis.10

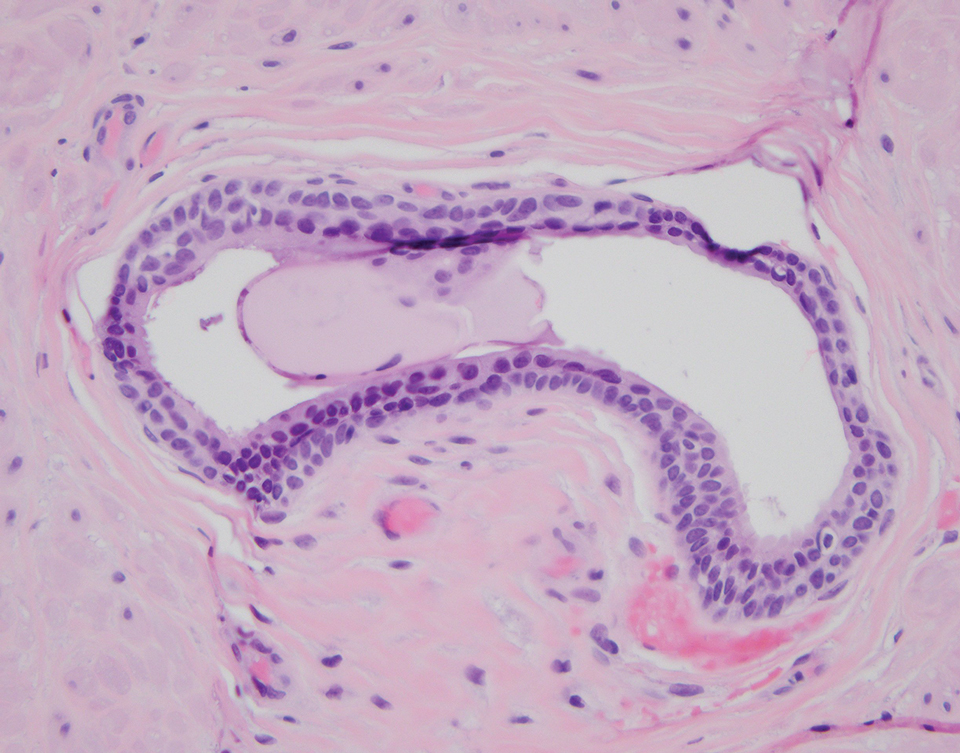

Urachal duct cyst develops from a remnant of the urachus that closed appropriately at the umbilicus and bladder but did not completely regress. It may manifest as an extraperitoneal mass at the umbilicus. Clinically, urachal duct cysts may be asymptomatic until an inciting event (eg, inflammation, deposition of calculus, or malignancy) occurs.11 Histopathology shows cystically dilated structures lined with a transitional epithelium (Figure 5).12 Urachal duct cysts usually are diagnosed in children or young adults and subsequently are excised.11

- Harder C, Velho RV, Brandes I, et al. Assessing the true prevalence of endometriosis: a narrative review of literature data. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;167:883-900. doi:10.1002/ijgo.15756

- Lopez-Soto A, Sanchez-Zapata MI, Martinez-Cendan JP, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: presentation of 33 cases and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Feb 2018;221:58-63. doi:10.1016 /j.ejogrb.2017.11.024

- Dridi D, Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, et al. Umbilical endometriosis: a systematic literature review and pathogenic theory proposal. J Clin Med. 2022;11:995. doi:10.3390/jcm11040995

- Farooq U, Laureano AC, Miteva M, Elgart GW. Cutaneous endometriosis: diagnostic immunohistochemistry and clinicopathologic correlation. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:525-528. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01681.x

- Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Endometriosis-associated extraovarian malignancies: a challenging question for the clinician and the pathologist. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2429-2438. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14212

- Ronen S, Suster D, Chen WS, et al. Histologic patterns of cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 232 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:401-411. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001841

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31821a4d33

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181954187

- Powell FC, Cooper AJ, Massa MC, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: a clinical and histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:610-615. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80265-0

- Hugen N, Kanne H, Simmer F, et al. Umbilical metastases: real-world data shows abysmal outcome. Int J Cancer. 2021;149: 1266-1273. doi:10.1002/ijc.33684

- Al-Salem A. An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology. 1st ed. Springer Cham; 2016.

- Schubert GE, Pavkovic MB, Bethke-Bedürftig BA. Tubular urachal remnants in adult bladders. J Urol. 1982;127:40-42. doi:10.1016/s0022- 5347(17)53595-8

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the ectopic presence of endometrial tissue and occurs in approximately 13% of women of childbearing age.1 This non-neoplastic lesion can manifest on the skin in less than 5.5% of endometriosis cases worldwide. Historically, secondary cutaneous endometriosis (CE) most frequently has been associated with prior gynecologic surgery (often cesarean section)2; however, an increased incidence of primary CE in patients without prior surgical history recently has been documented in the literature.3 While secondary CE usually manifests at the site of a surgical scar, primary CE has a predilection for the umbilicus (Villar nodule). In both primary and secondary CE, patients present clinically with a solitary nodule and abdominal pain that may be exacerbated during menstruation. Bleeding without associated pain may be more common in primary CE, while bleeding with pain may be more common in secondary CE. Cutaneous endometriosis often is overlooked given its low incidence, leading to delayed diagnosis. Primary CE often is misdiagnosed clinically as a pyogenic granuloma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, or keloid, while secondary CE may be mistaken for a fibroma, incisional hernia, or granuloma.2

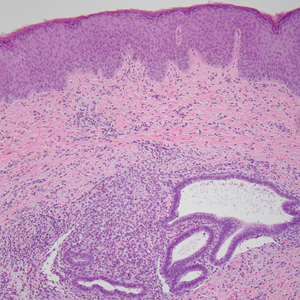

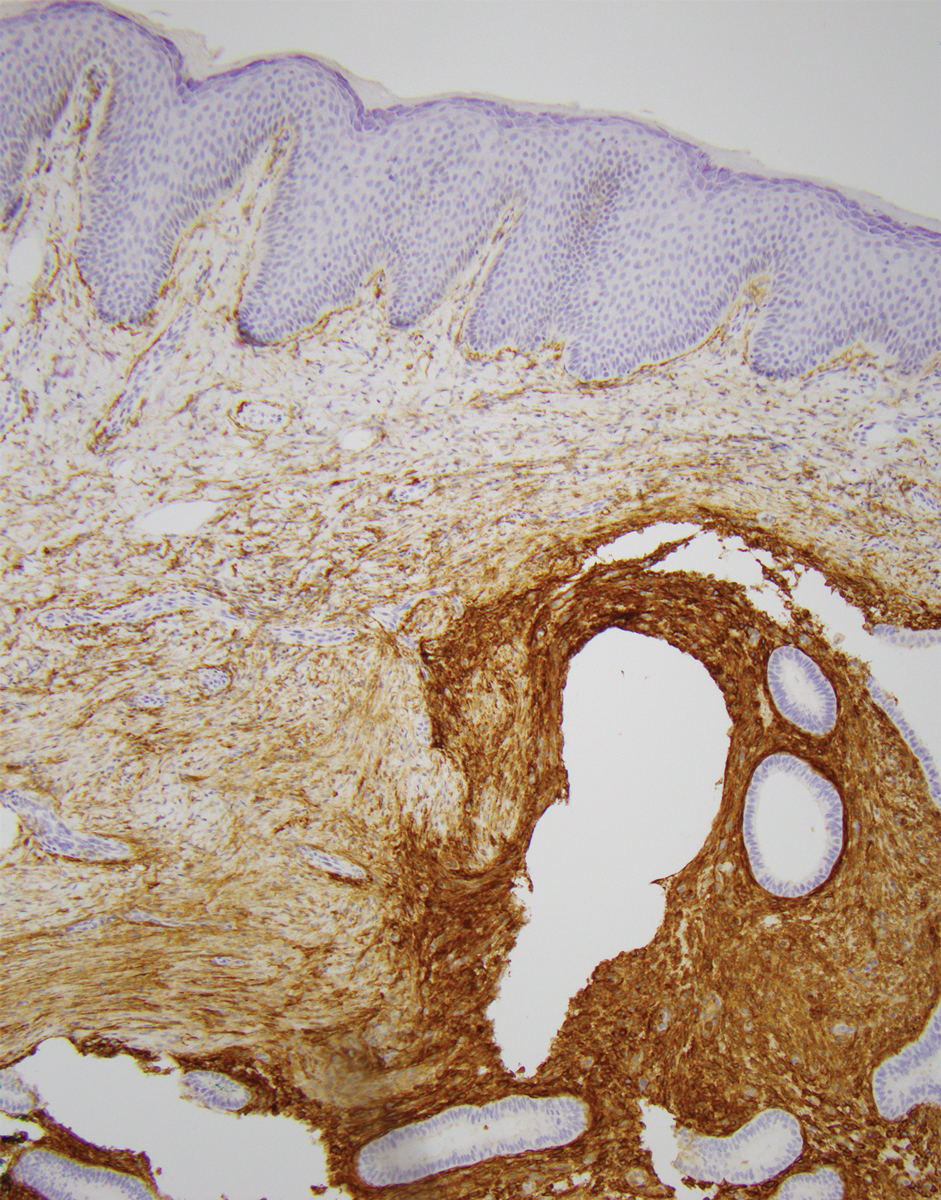

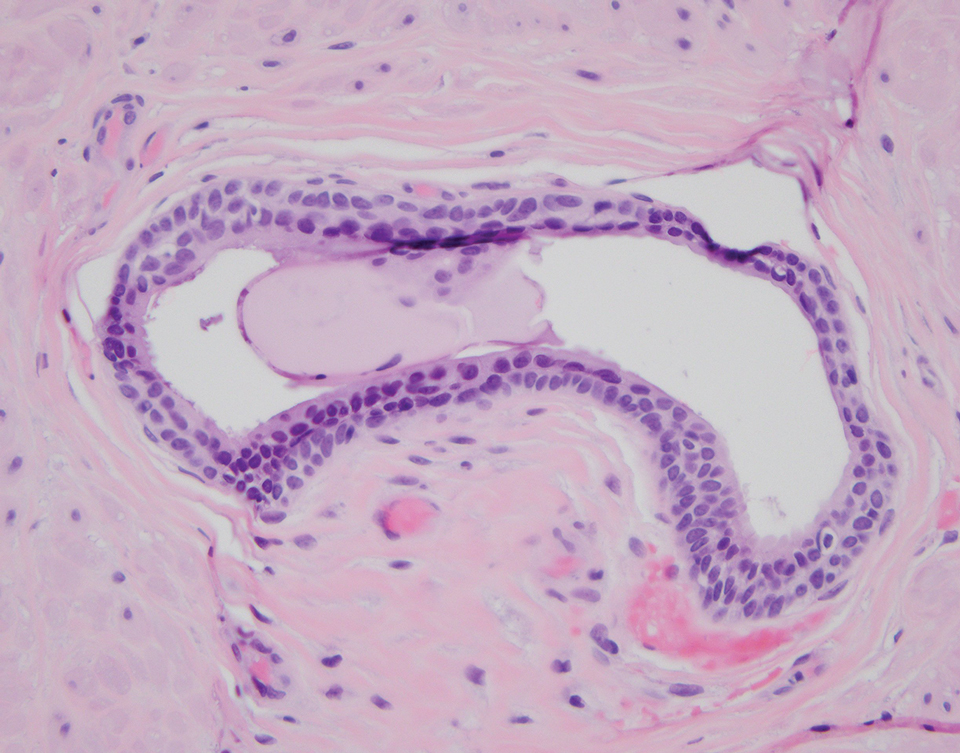

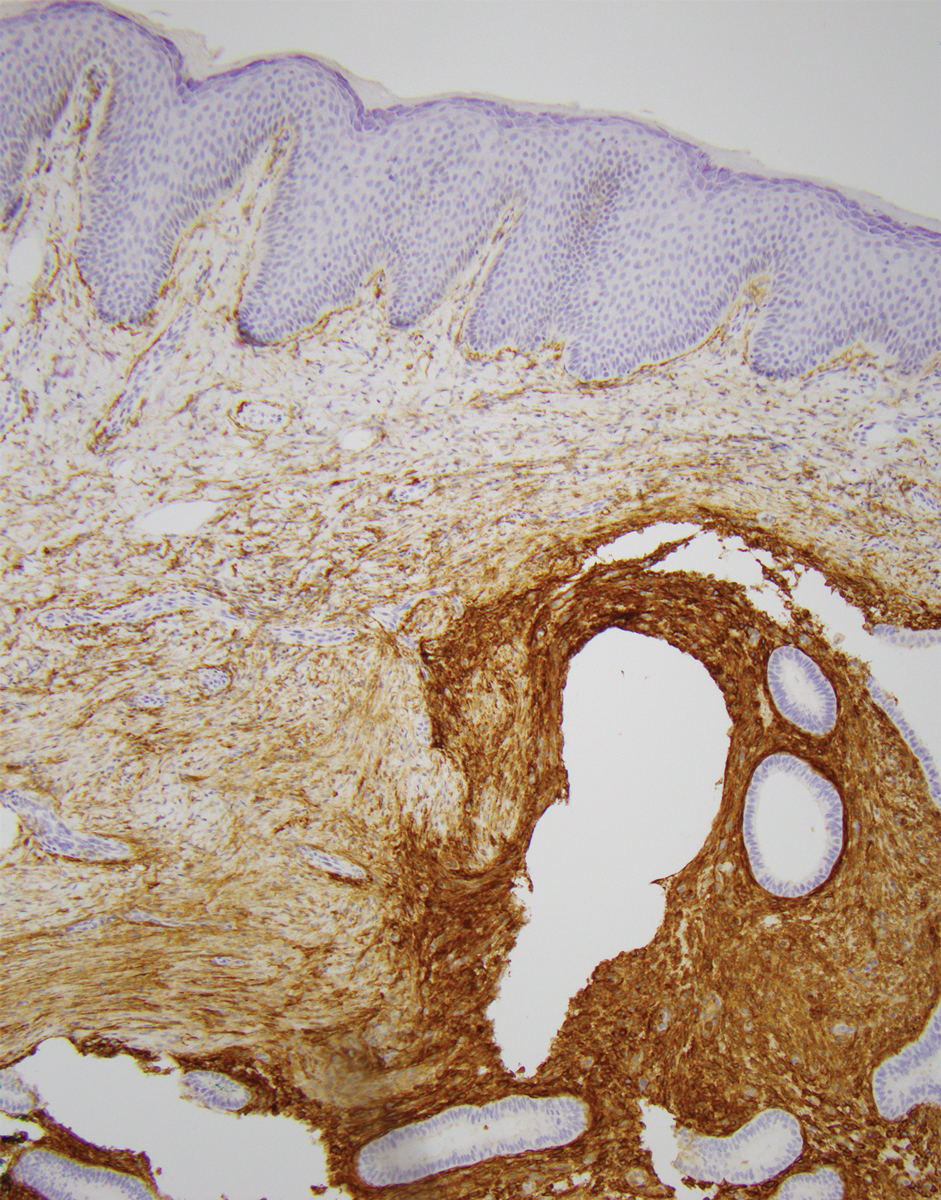

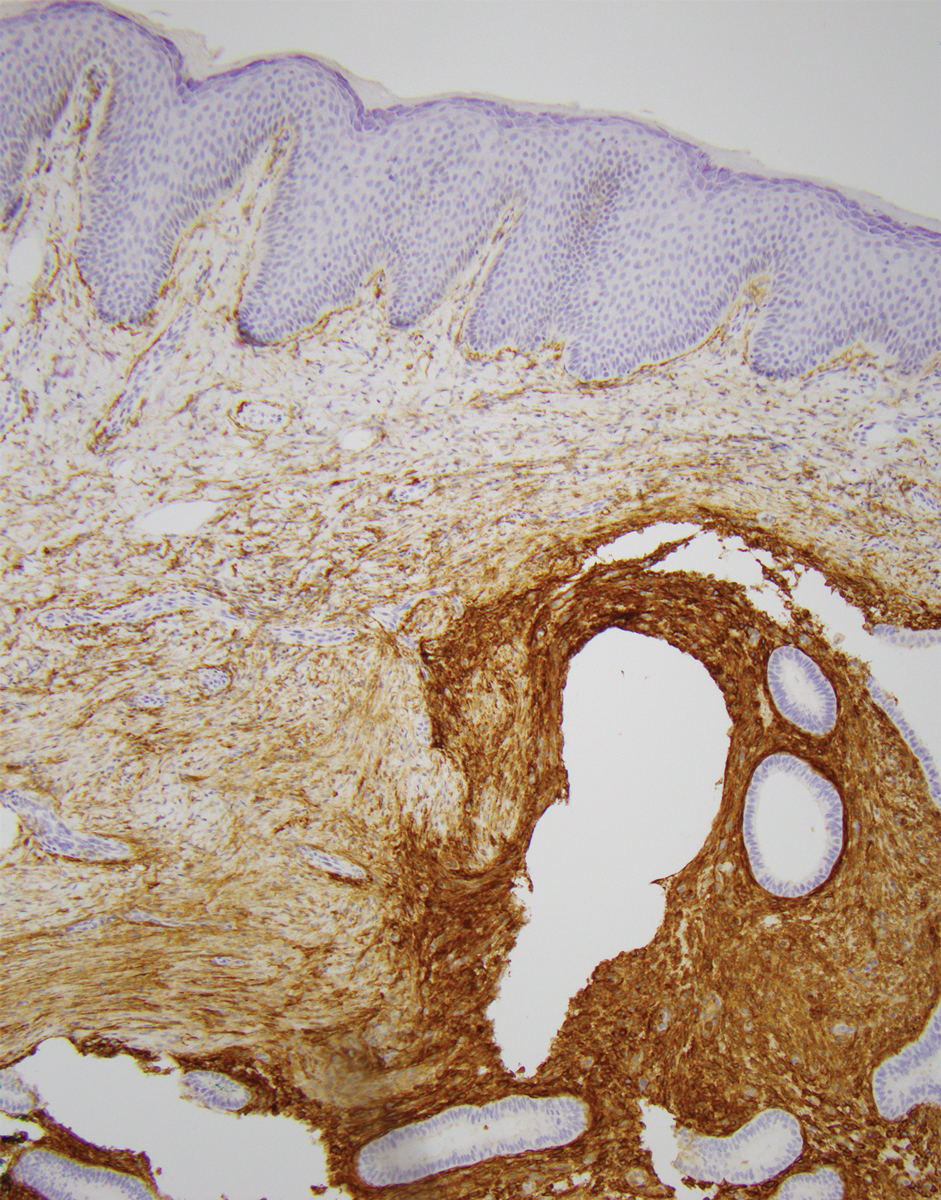

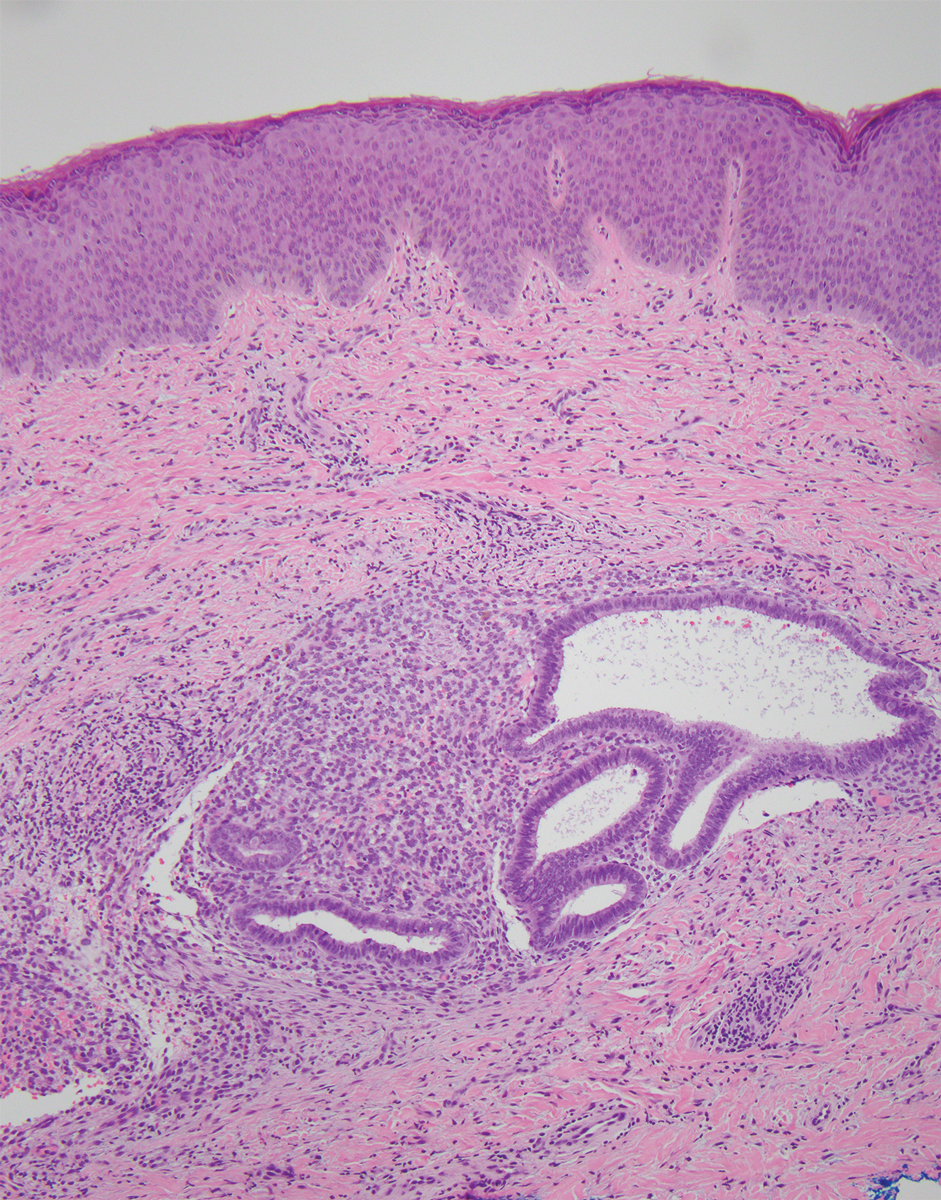

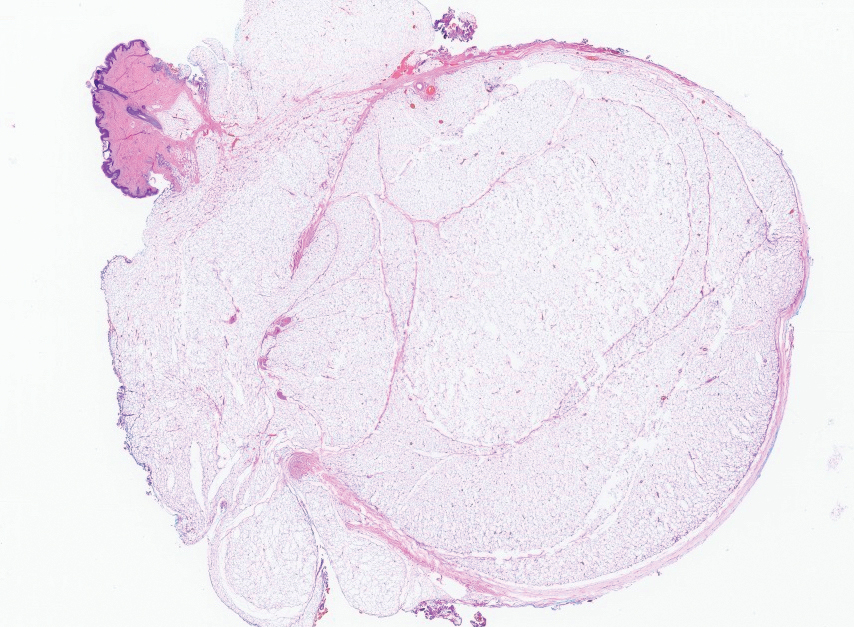

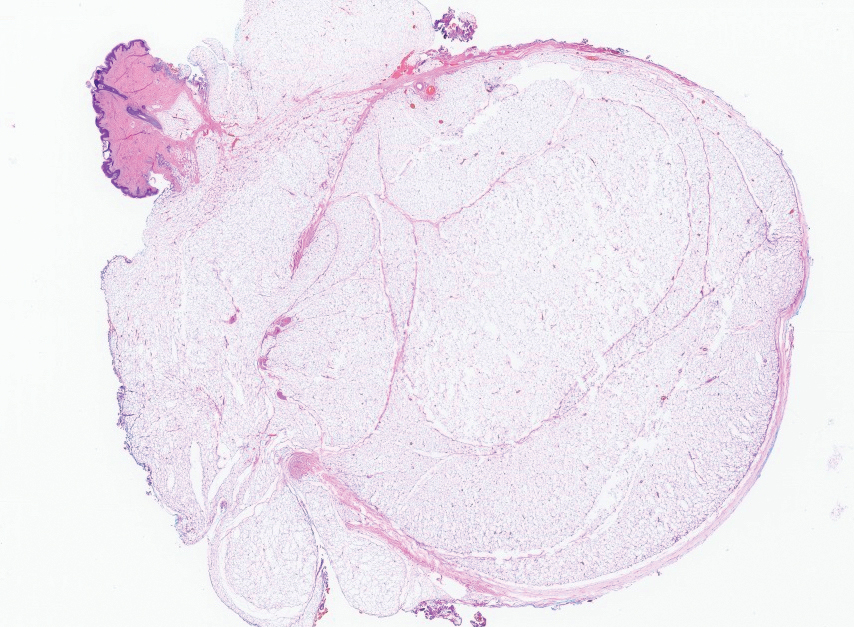

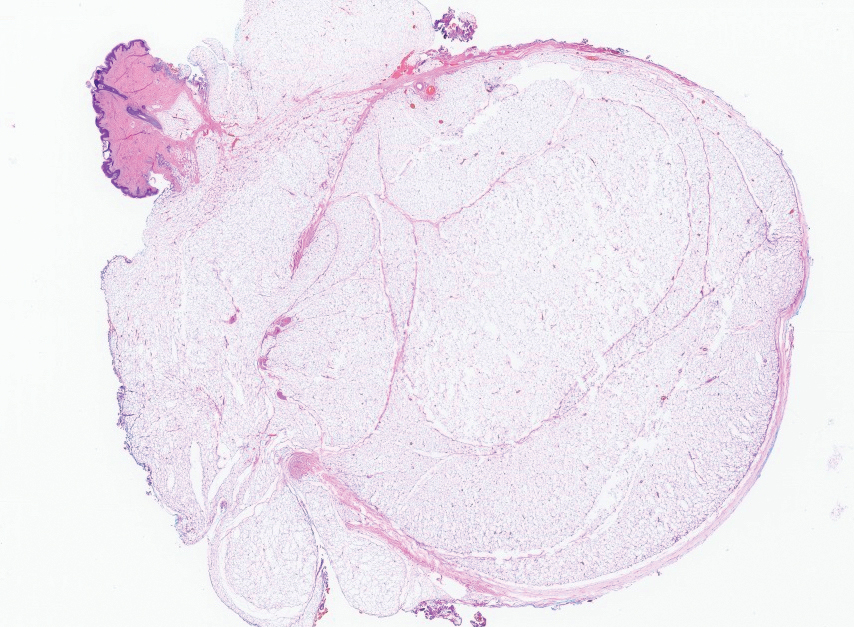

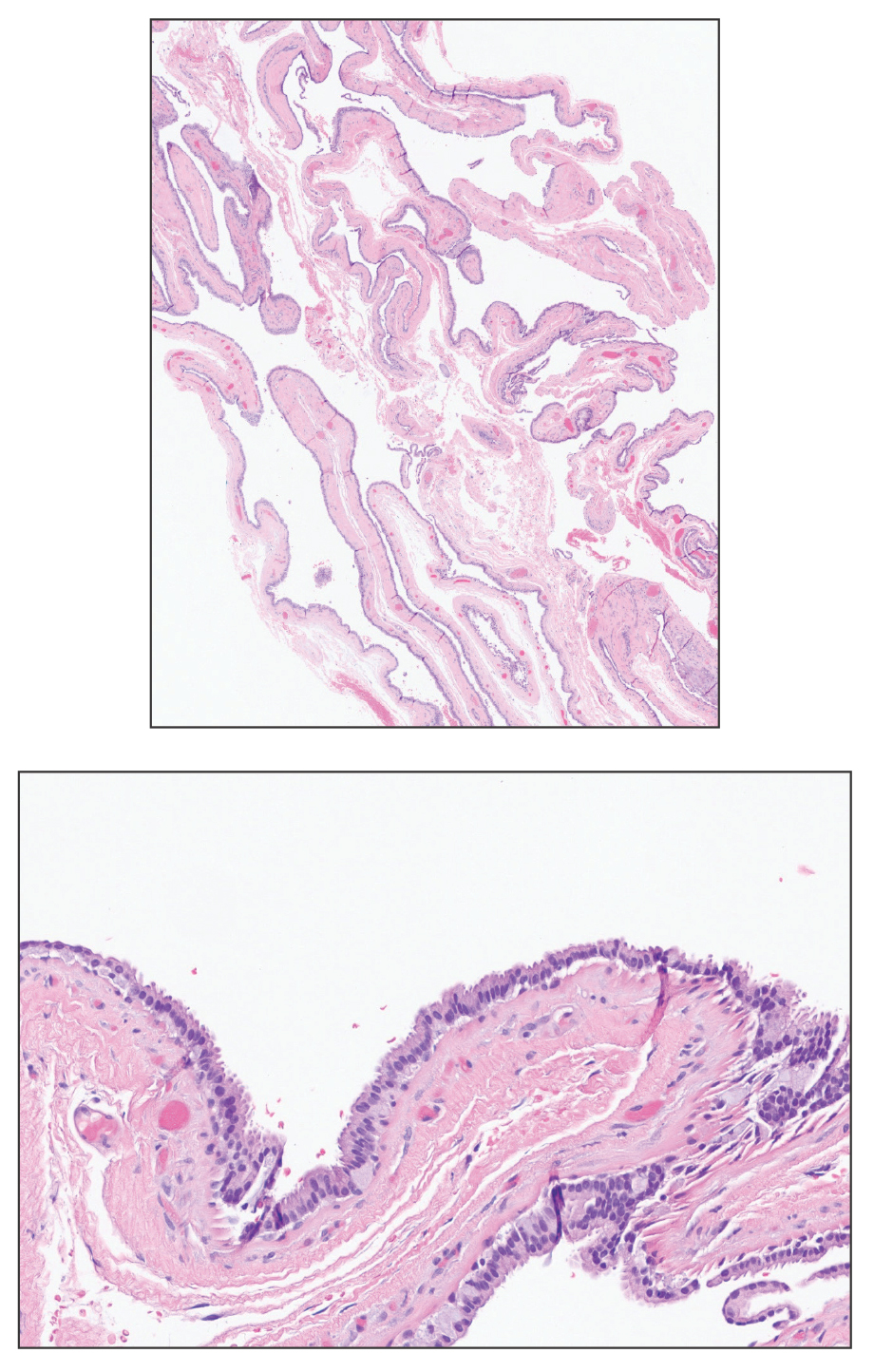

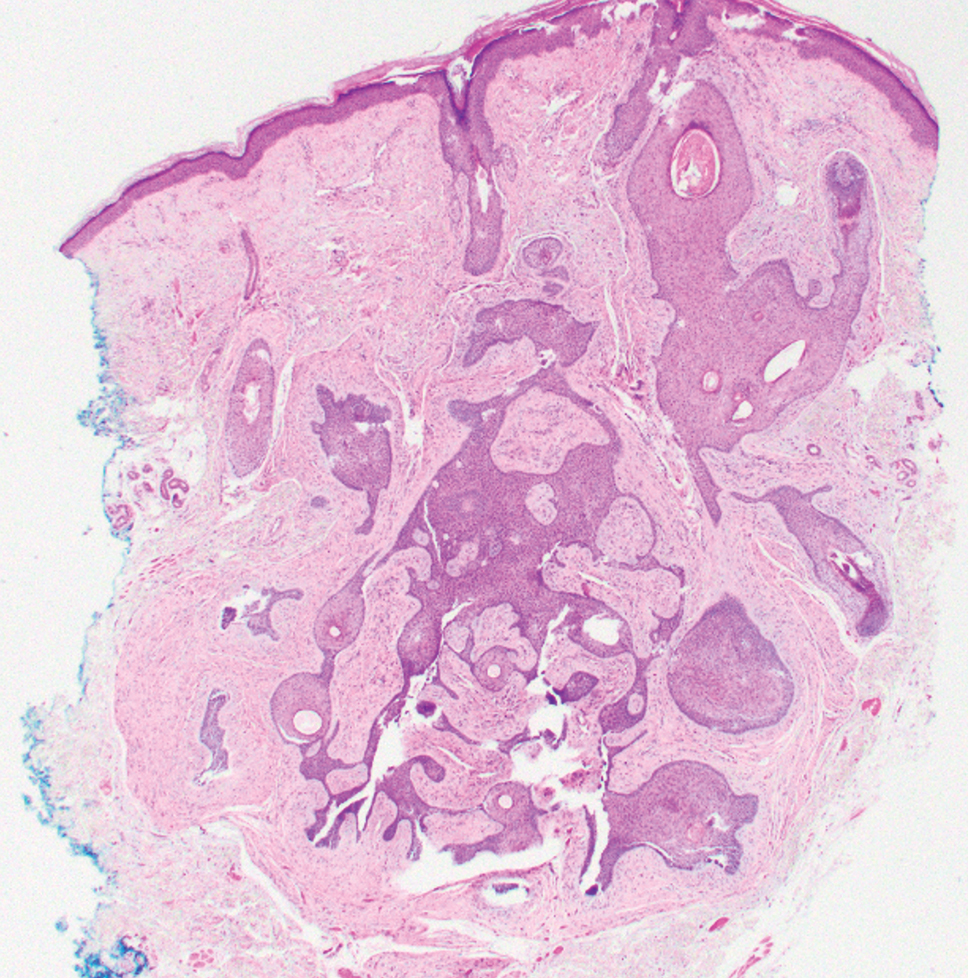

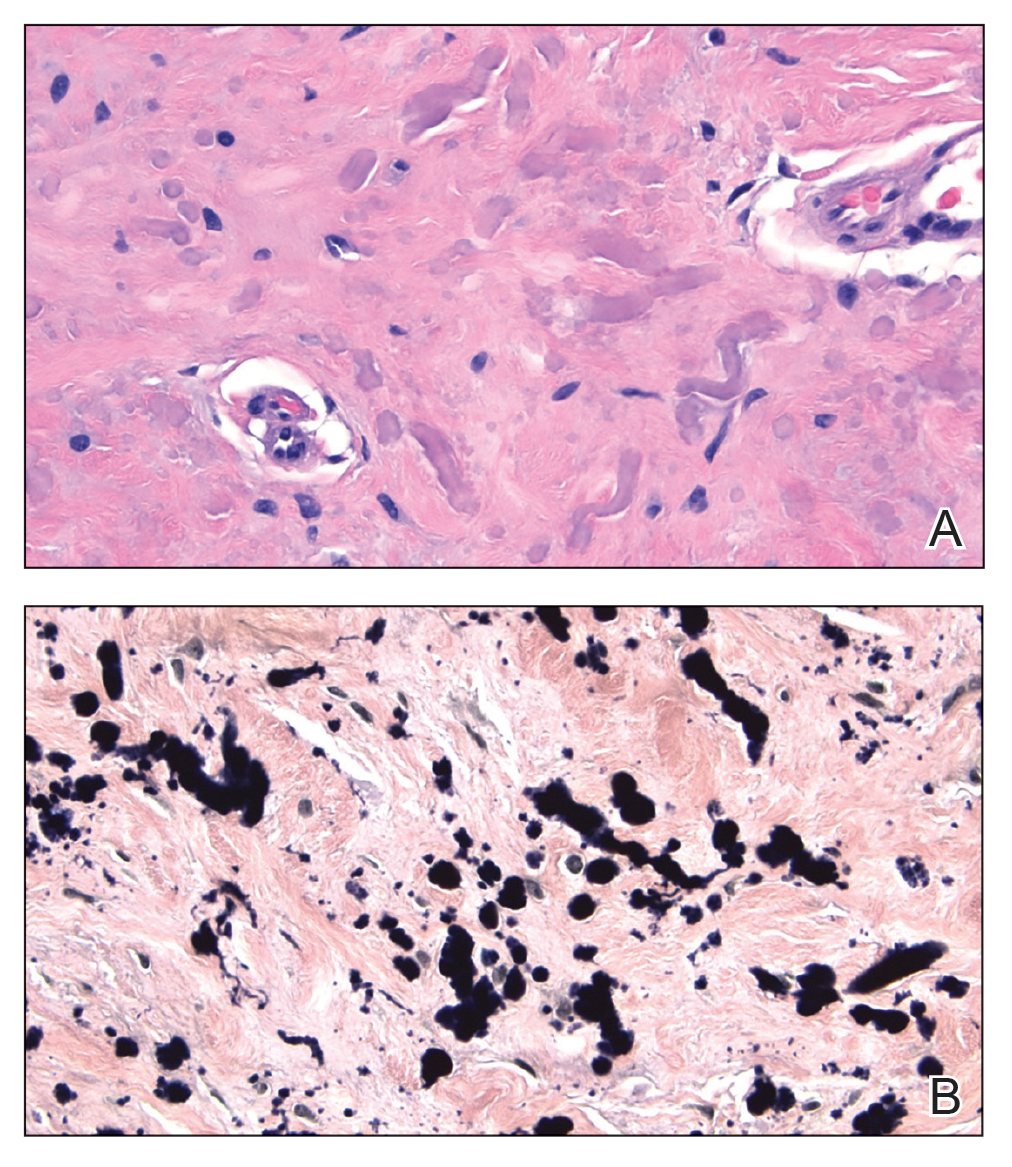

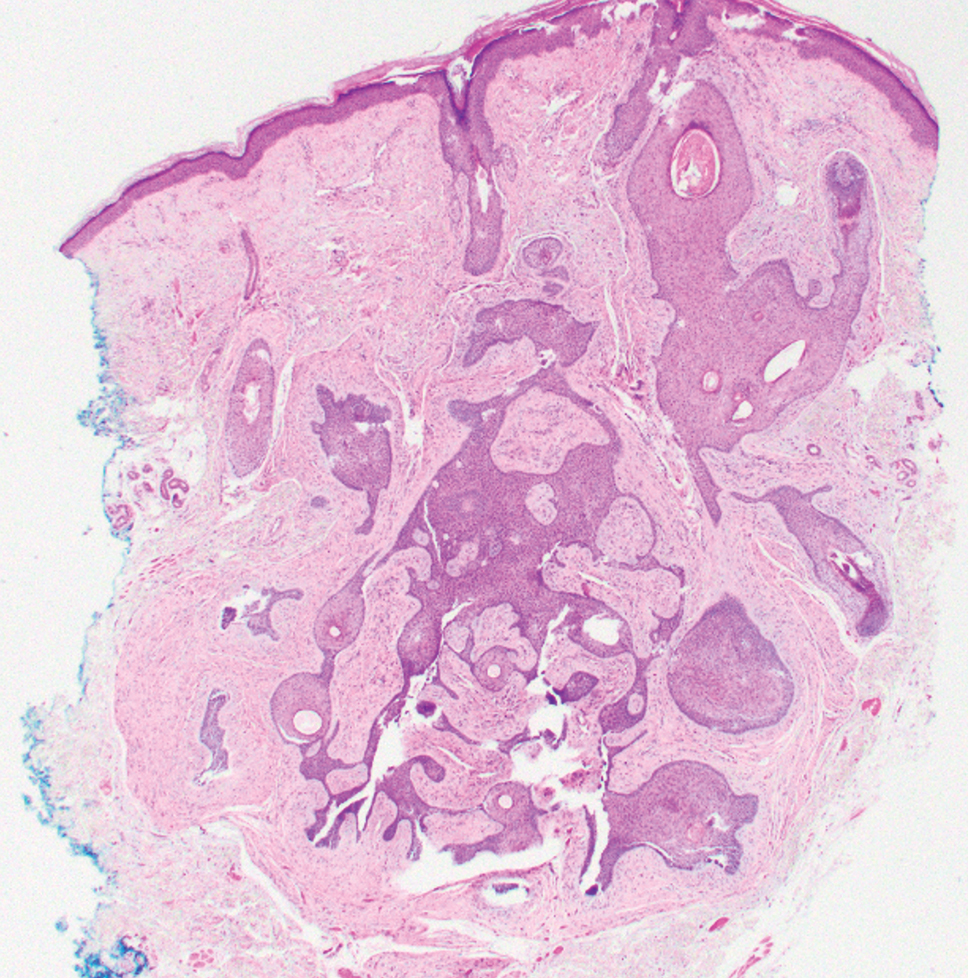

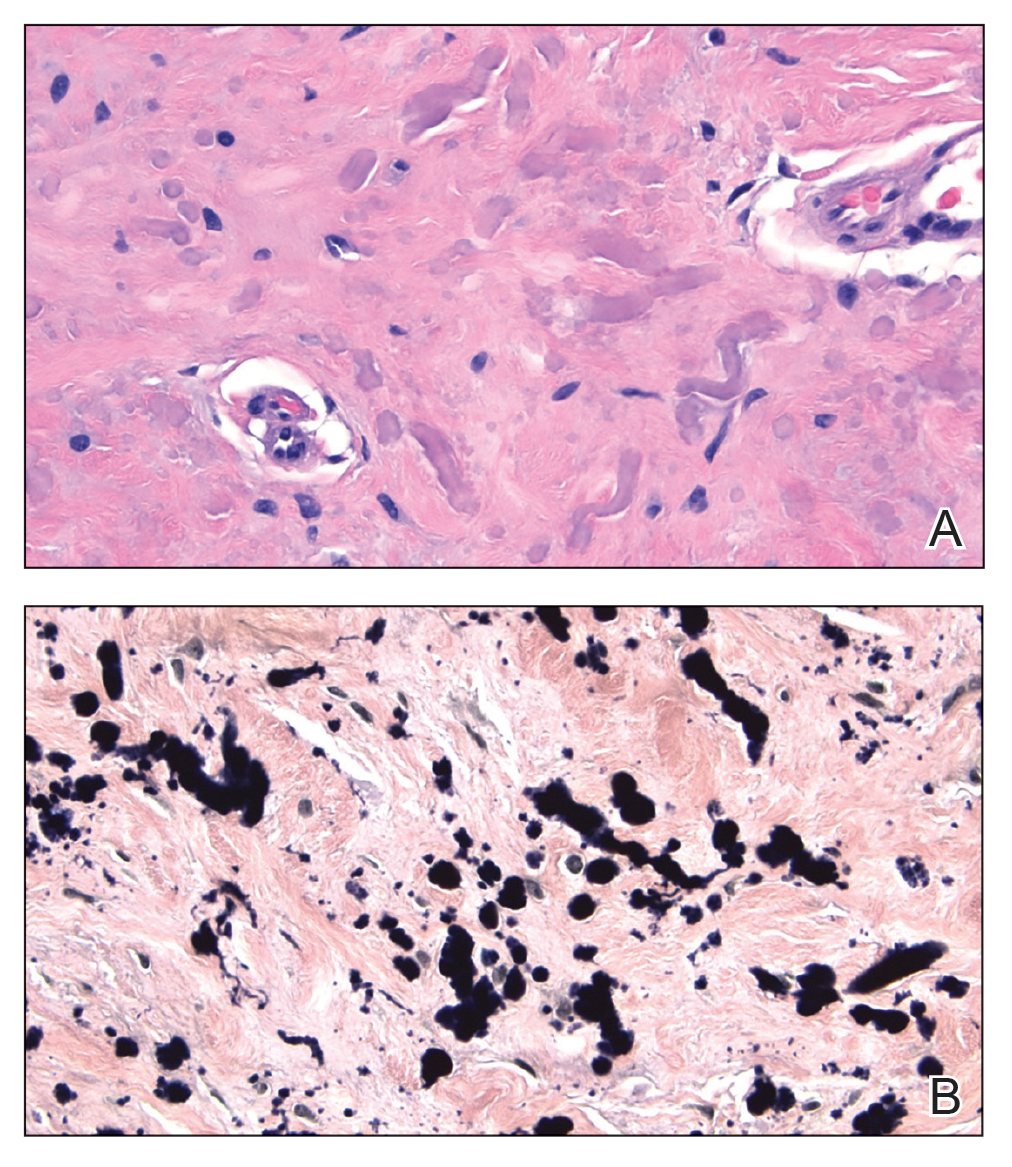

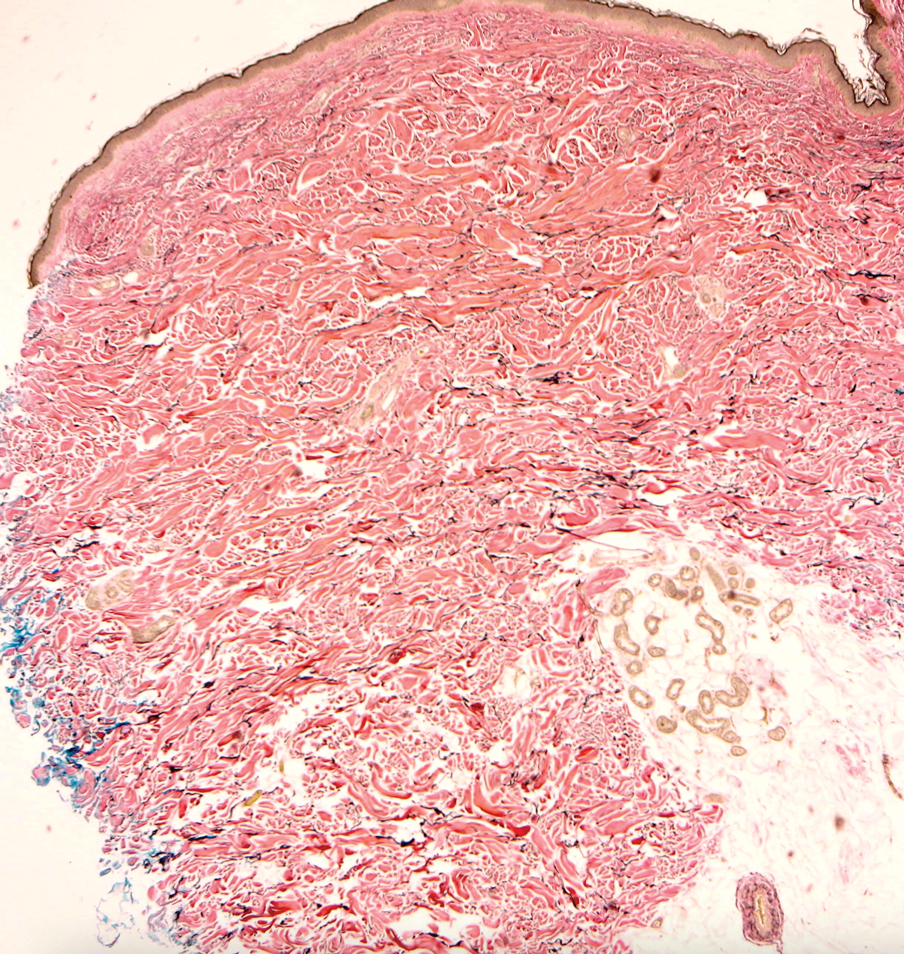

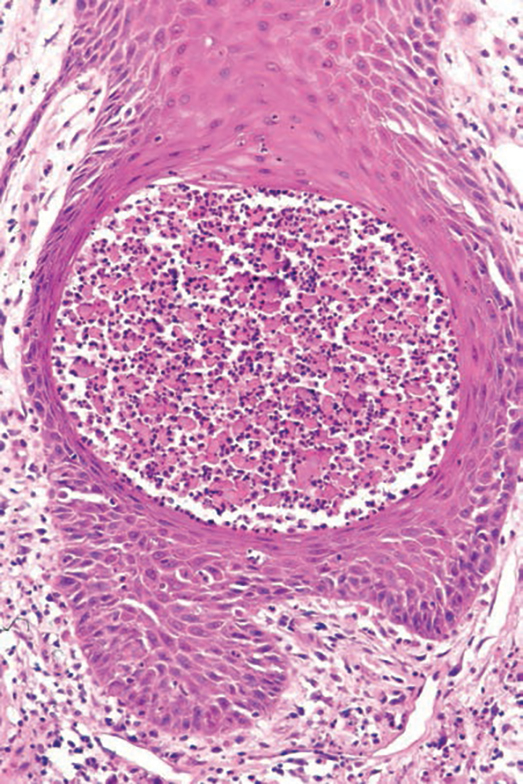

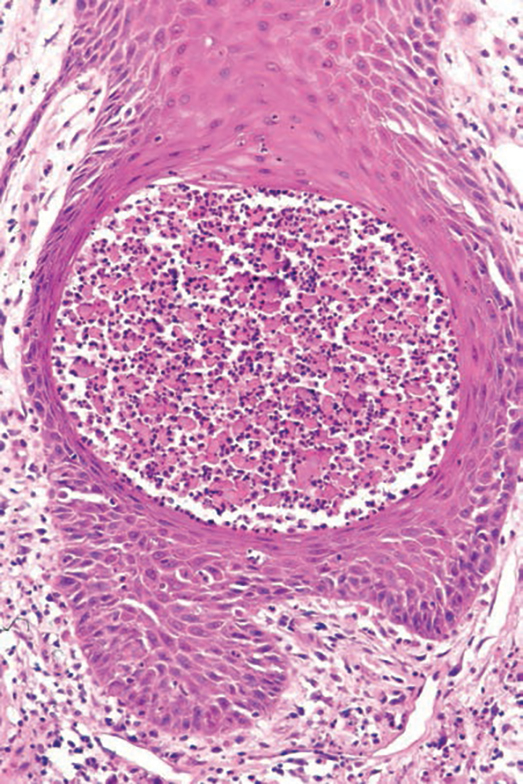

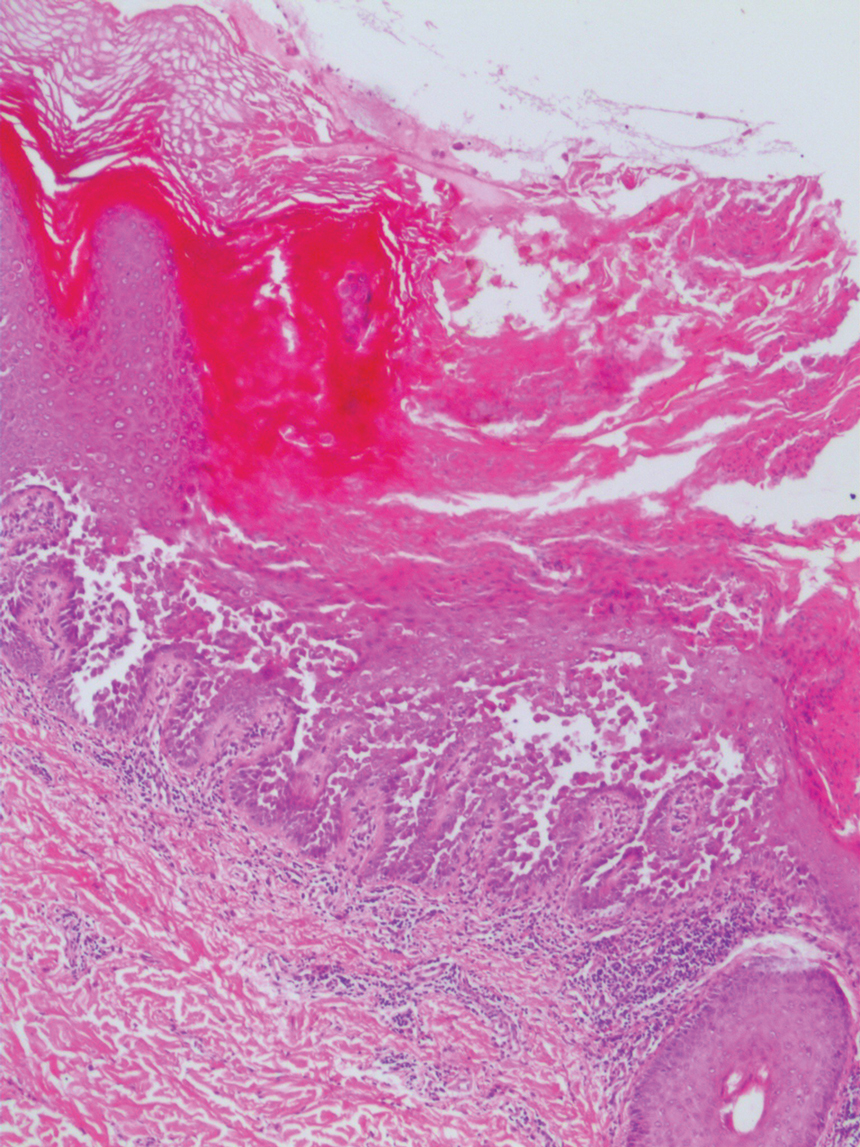

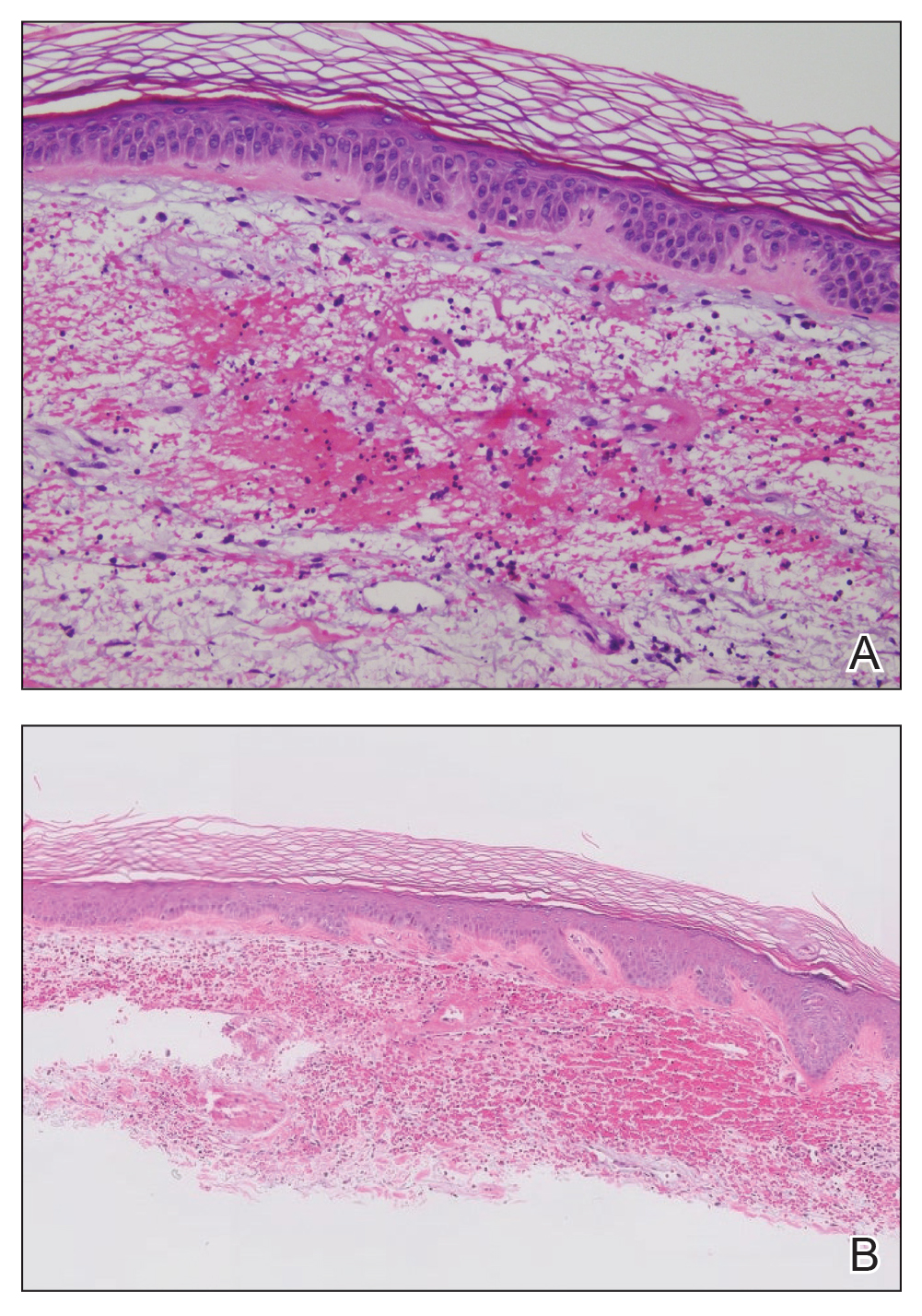

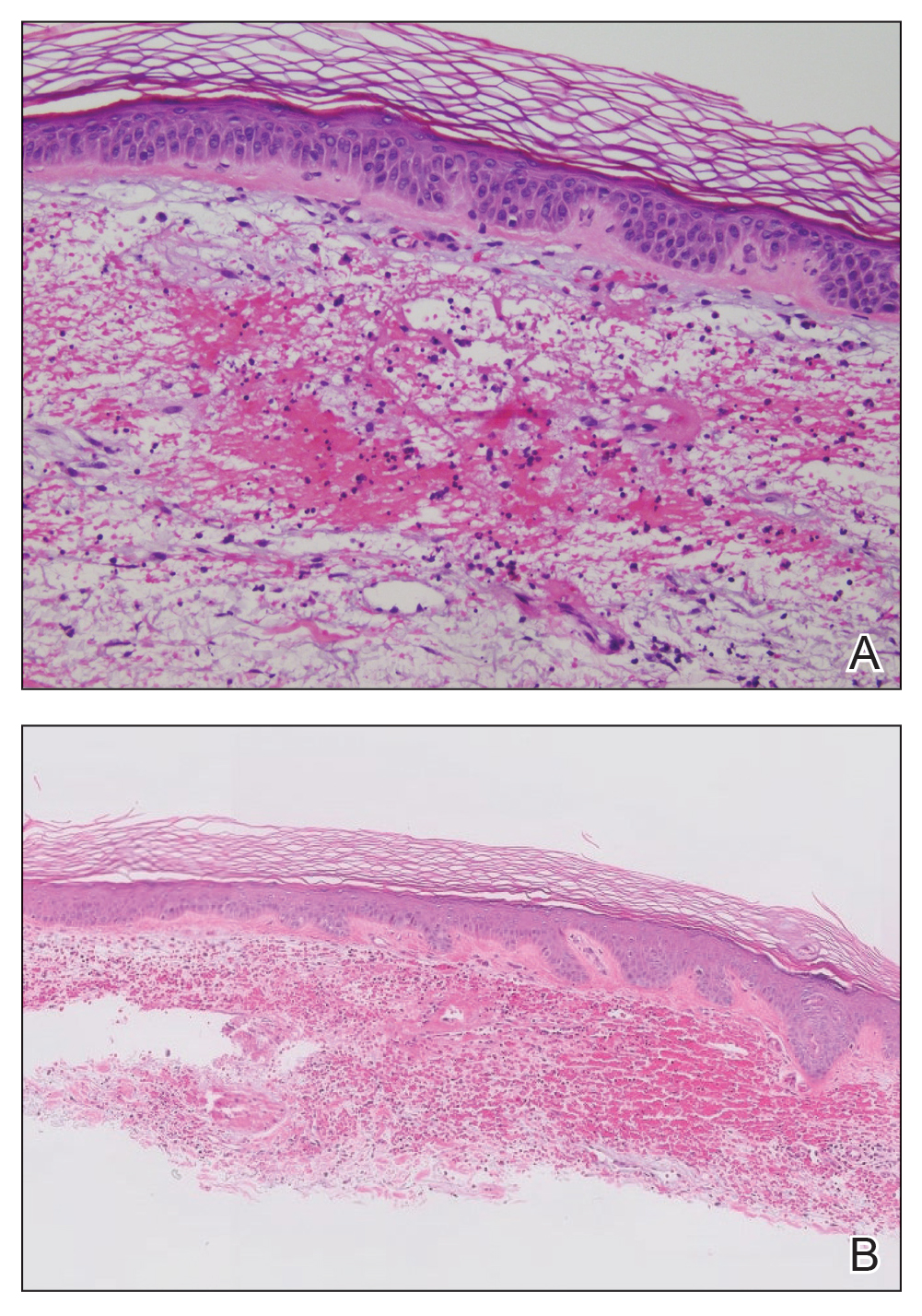

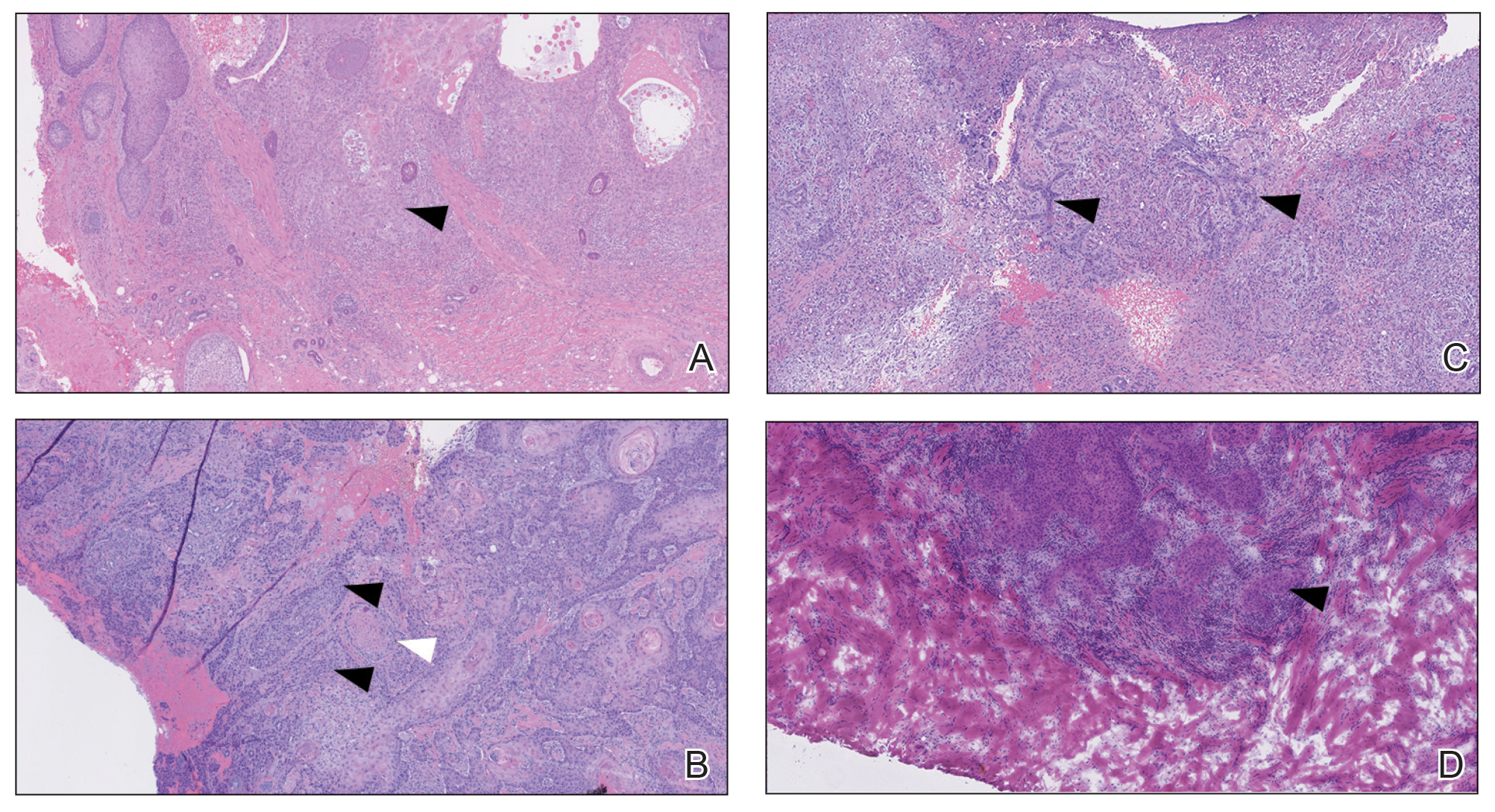

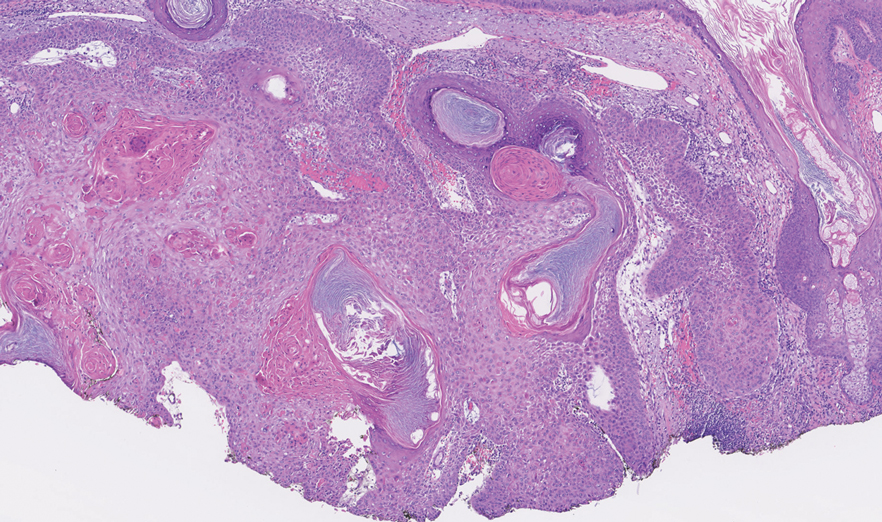

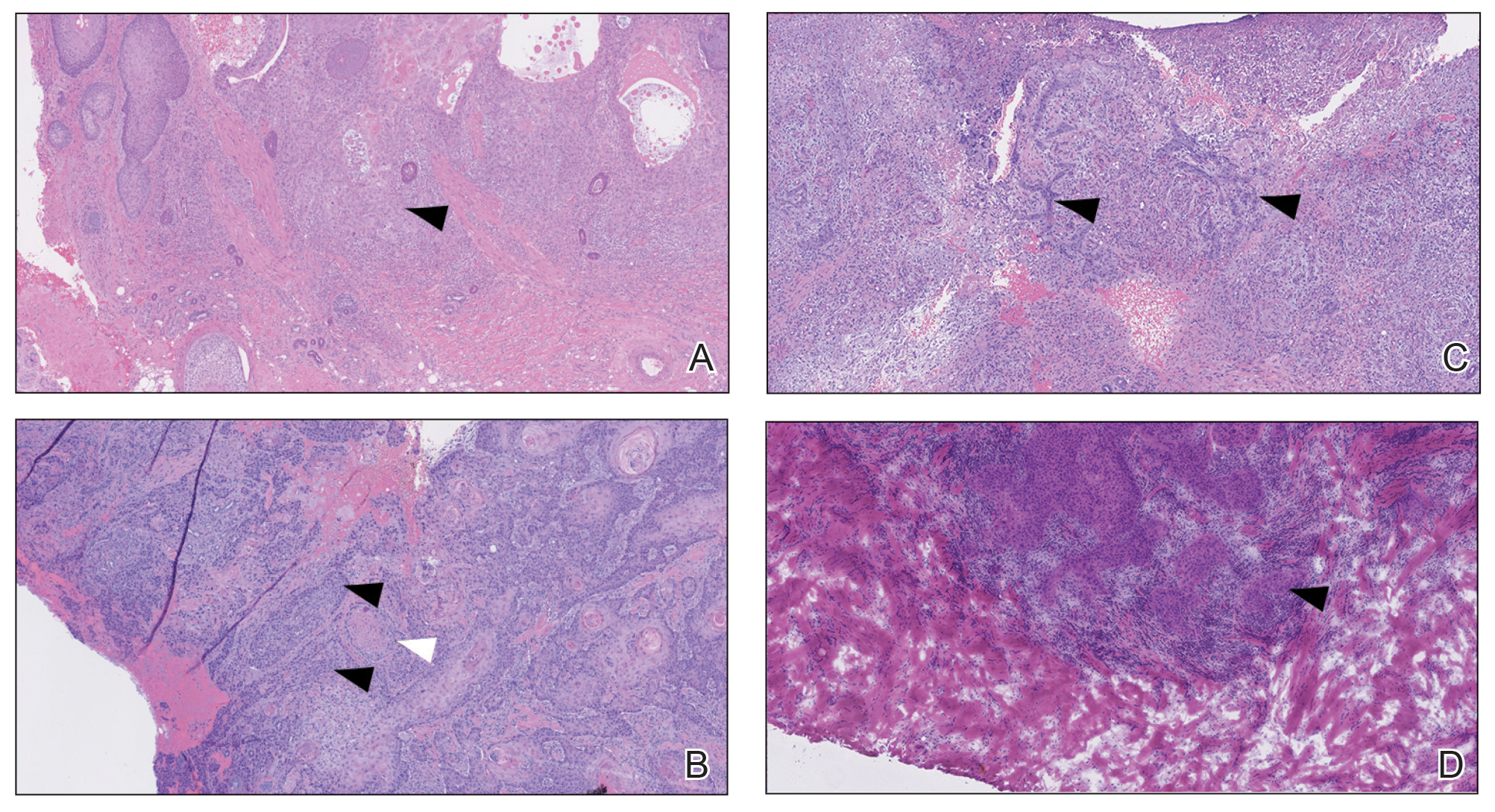

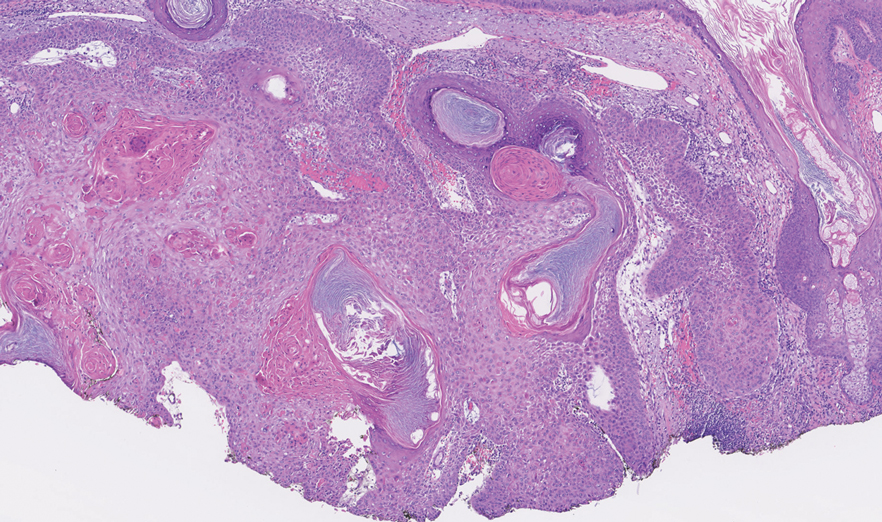

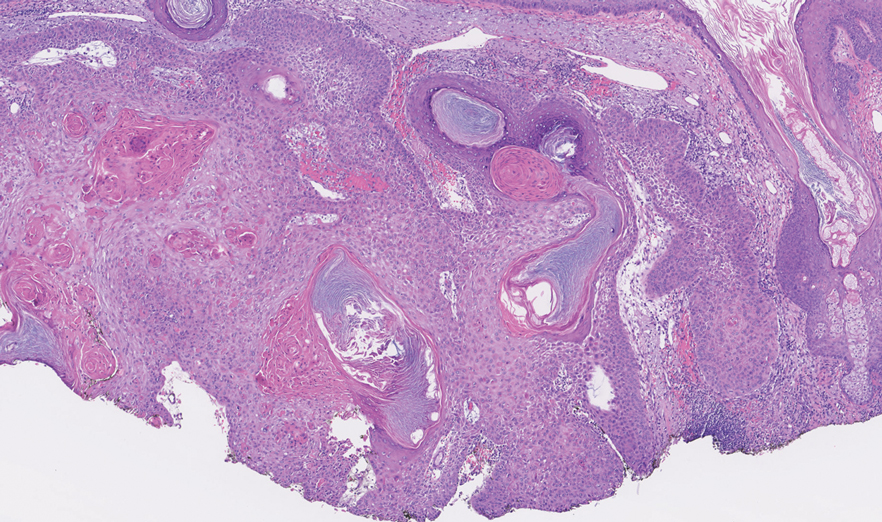

Primary and secondary CE have identical histopathologic features. Glands of variable size consisting of a single epithelial layer of columnar cells are present in the reticular dermis or subcutis (quiz image).4 The accompanying periglandular stroma often is uniform, consisting of spindle-shaped basophilic cells with abundant vascular structures. The stroma may contain moderate numbers of mitotic figures, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and extravasated red blood cells. The ectopic tissue may be inactive or display morphologic changes resembling those of the endometrium in the normal menstrual cycle.4 As the ectopic tissue progresses through the stages of menstruation, the glandular morphology also transforms. The proliferative stage demonstrates increased epithelial mitotic figures, the secretory stage exhibits intraluminal secretion, and during menstruation there are degenerative epithelial cells and evidence of vascular congestion. A mixture of glandular stages may be seen in biopsy results. Robust immunohistochemical expression of CD10 in the endometrial stroma can aid in diagnosis (Figure 1). Estrogen and progesterone receptor immunostaining also shows strong nuclear positivity, except in decidualized tissue.4 Unlike intestinal glands, endometrial glands do not express CDX2 or CK20.5 Complete surgical excision of CE usually is curative; however, recurrence has been documented in 10% (3/30) of cases.2

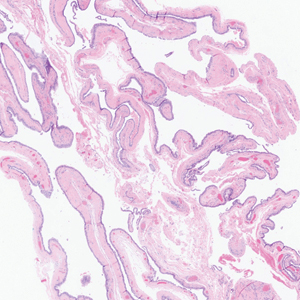

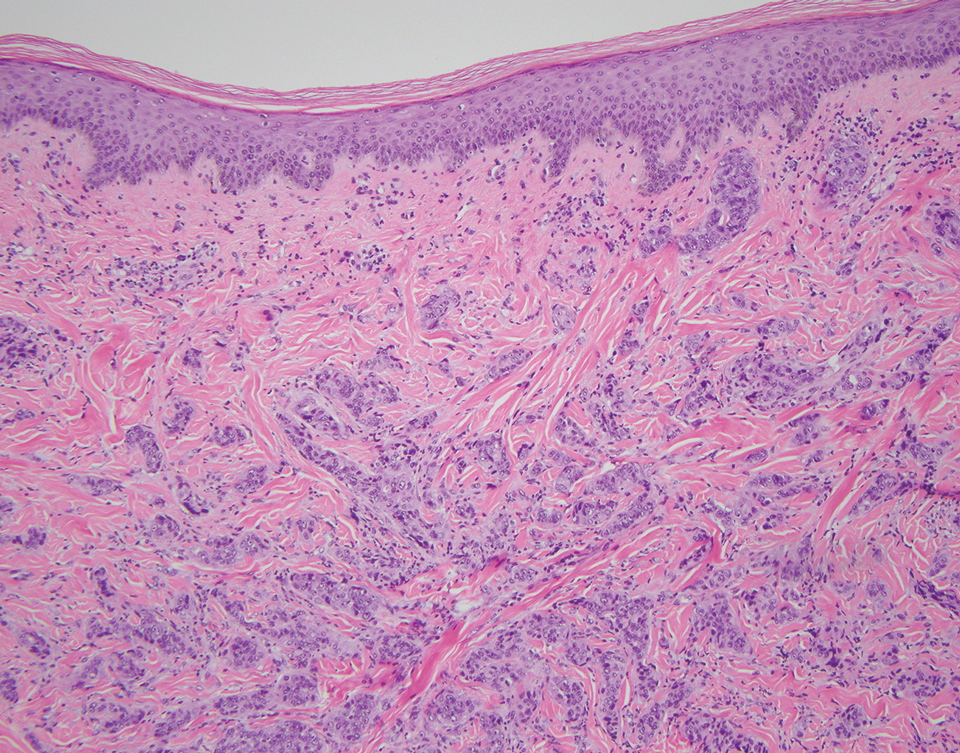

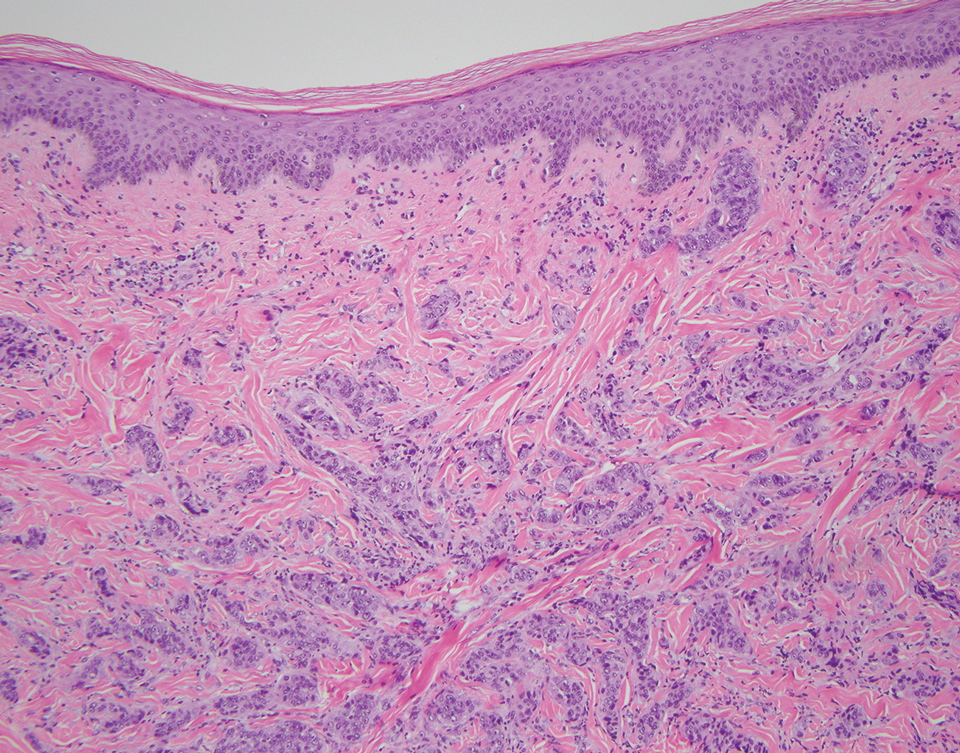

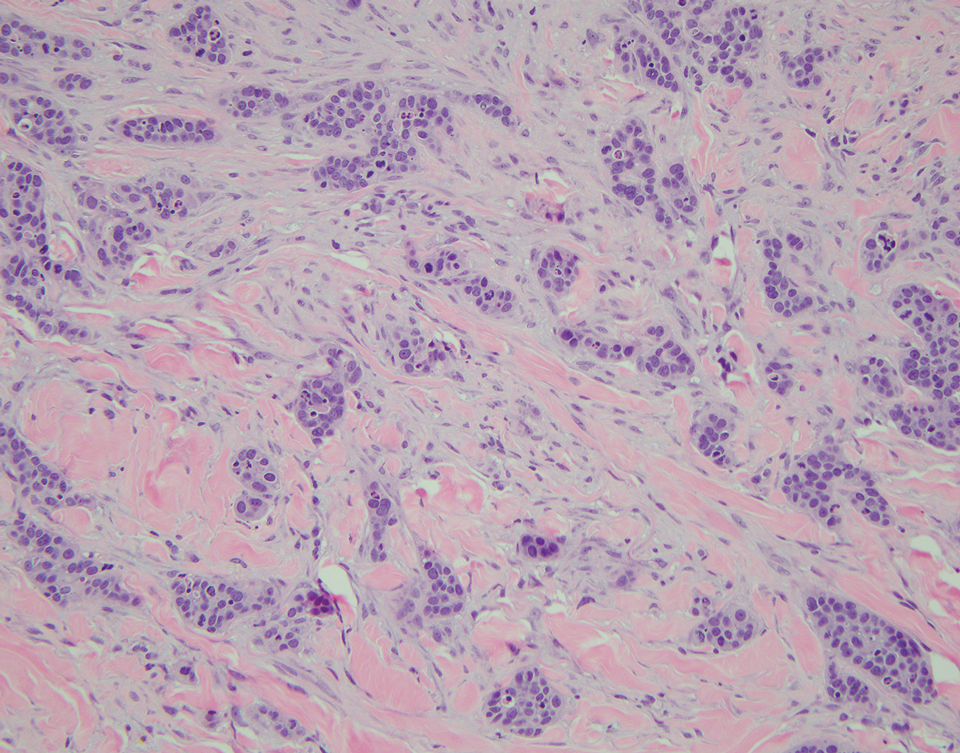

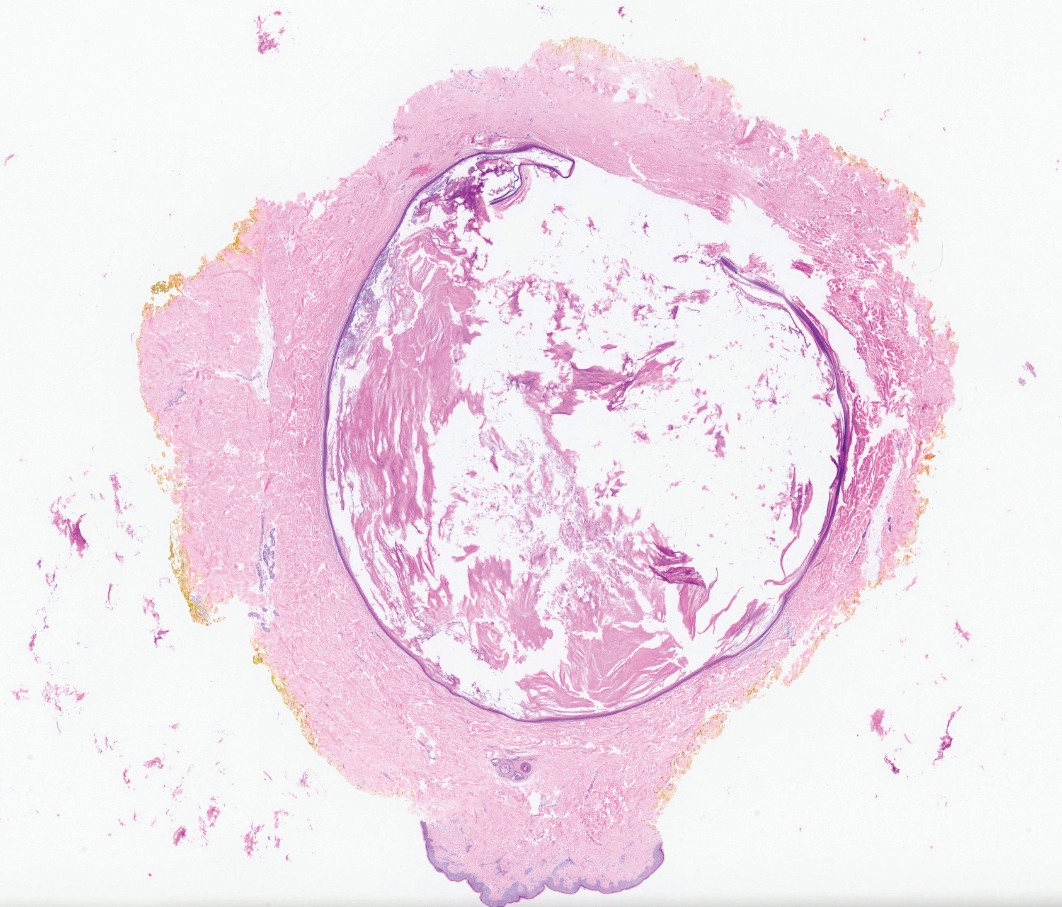

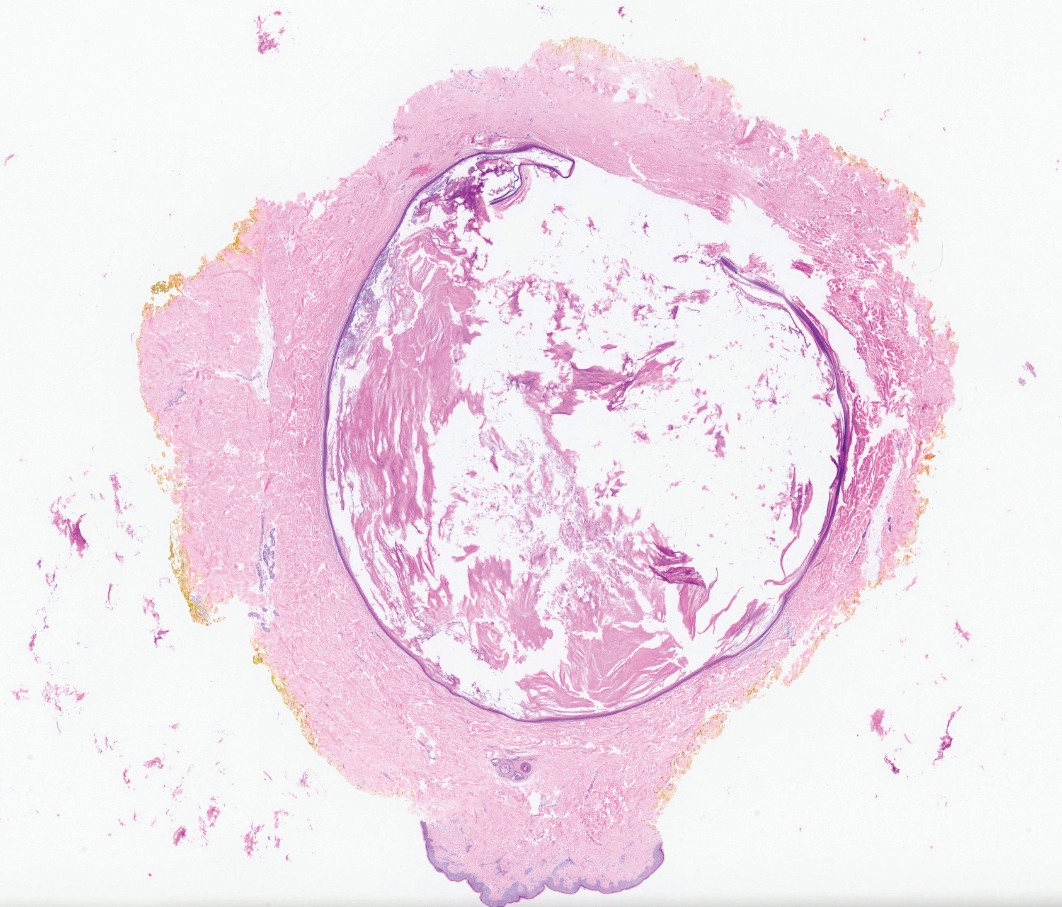

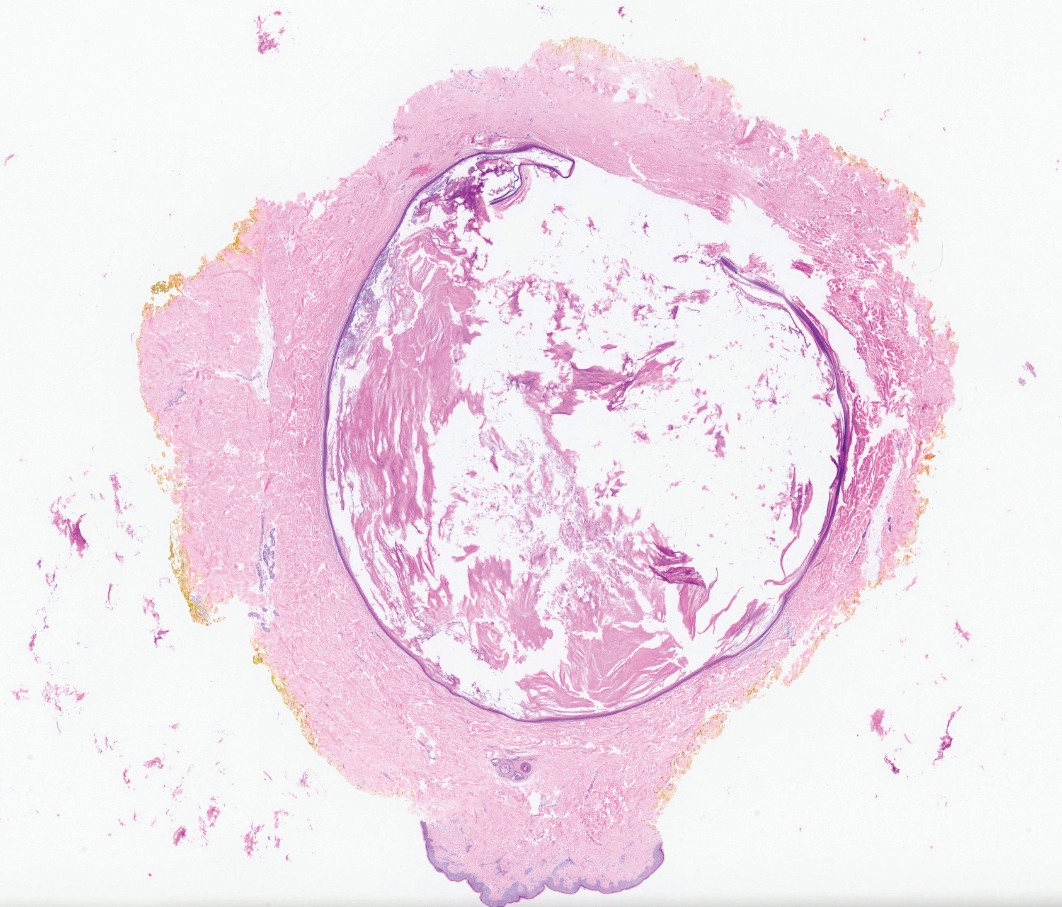

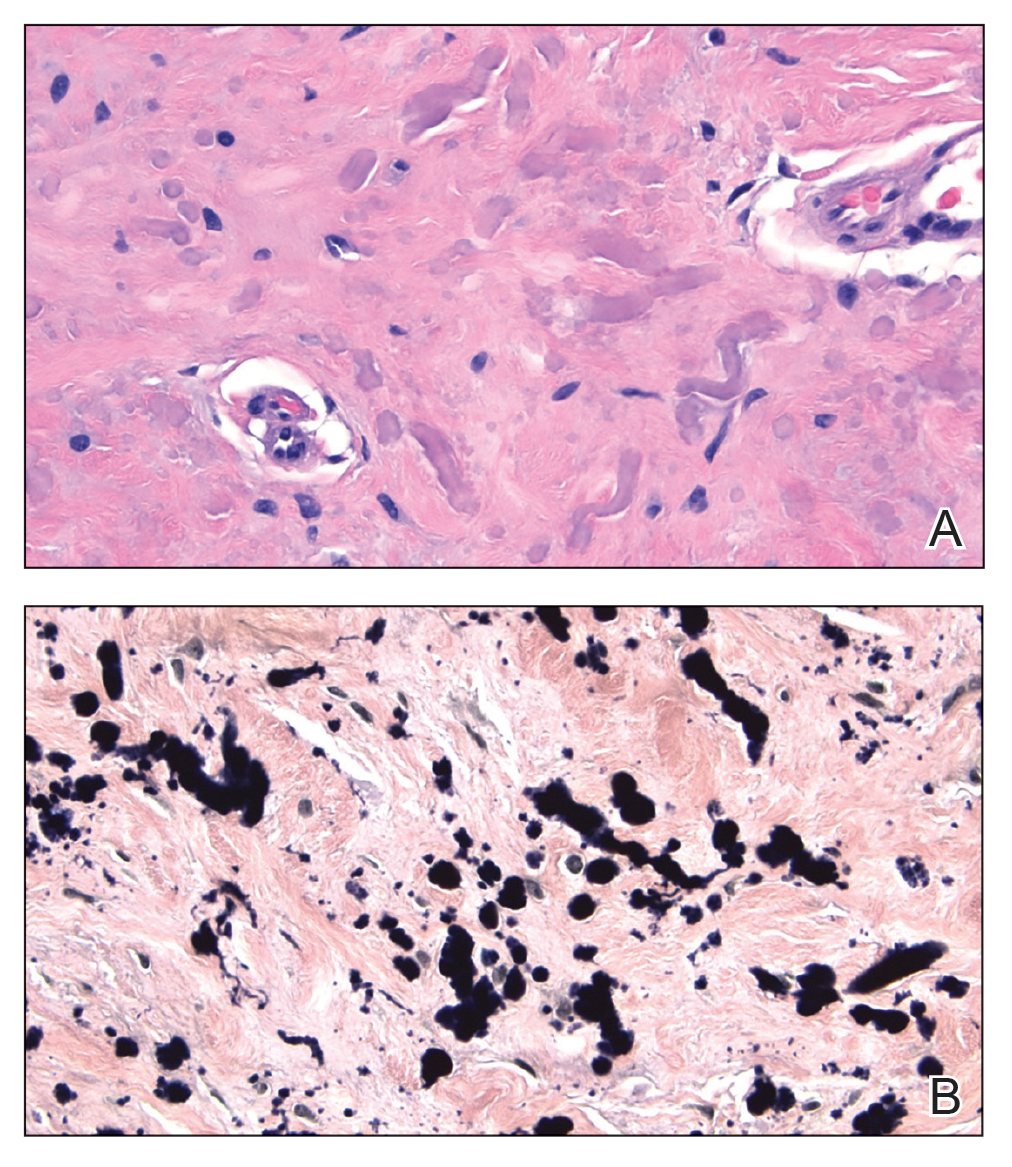

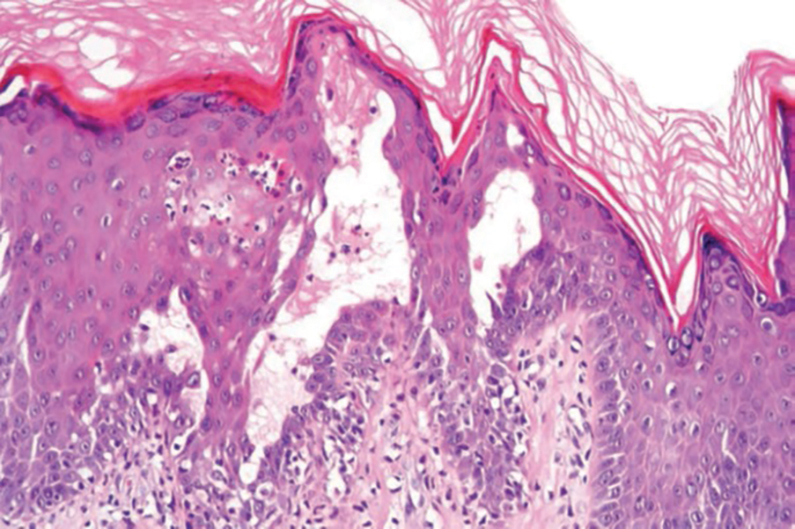

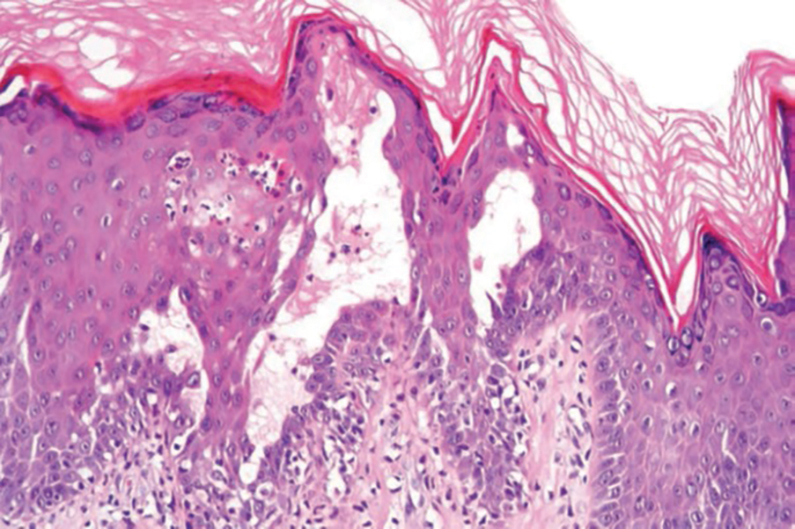

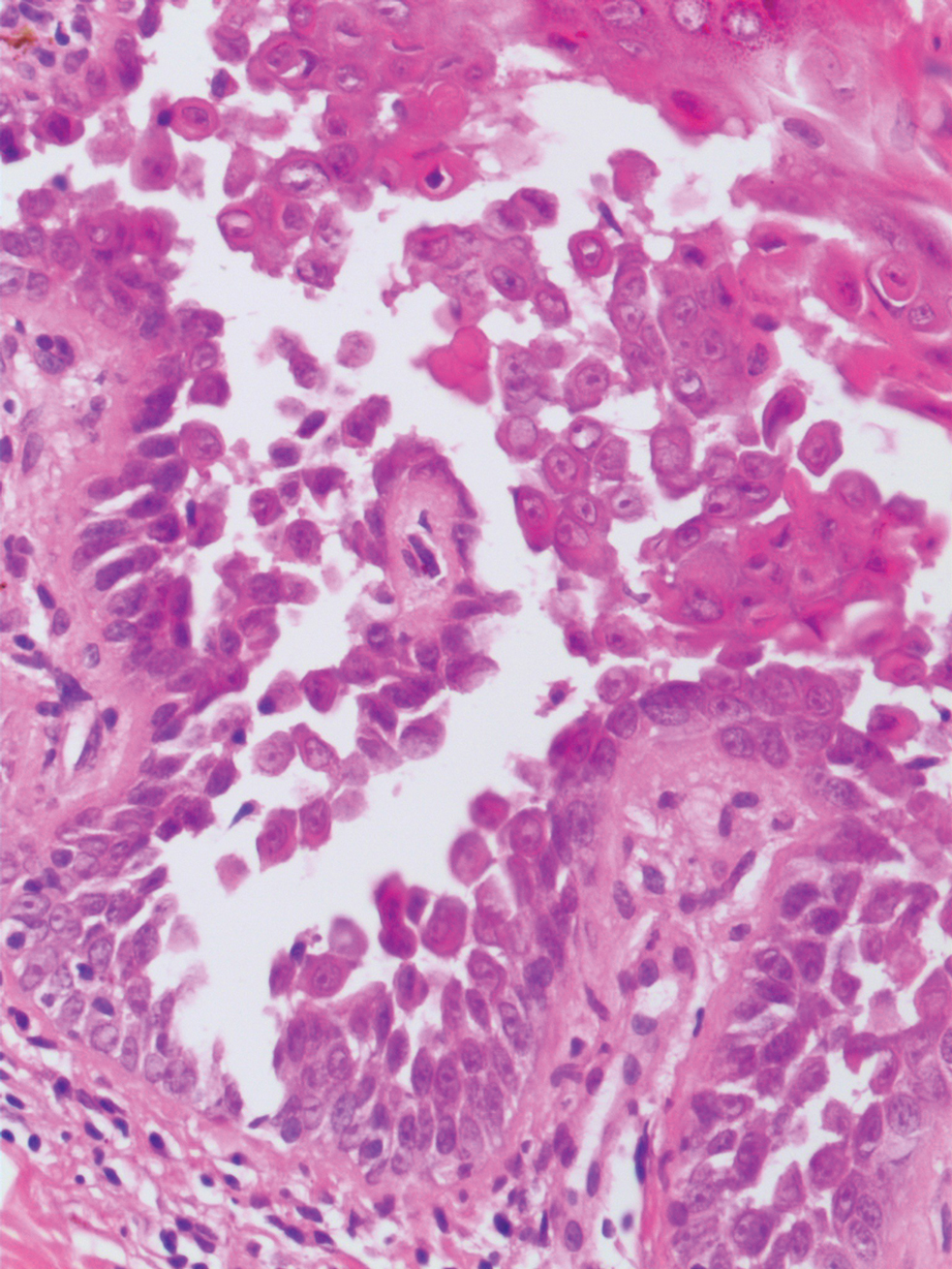

Breast carcinoma is the most common internal malignancy associated with cutaneous metastasis and may develop prior to visceral diagnosis. It is possible that tumor cells travel through the communicating networks of the cutaneous lymphatic ducts and the mammary lymphatic plexus; however, cutaneous manifestation often is located on the ipsilateral breast, and therefore tumor expansion rather than true metastasis cannot always be ruled out. On histopathology, findings of breast adenocarcinoma include tumor cells that tend to show either interstitial, nodular, mixed, or intravascular growth patterns (Figure 2). Tumor cells may invade the stroma in clusters or as individual cells. Sites of distant metastasis may show an increased likelihood of vascular and lymphatic invasion.6

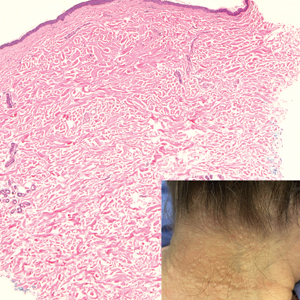

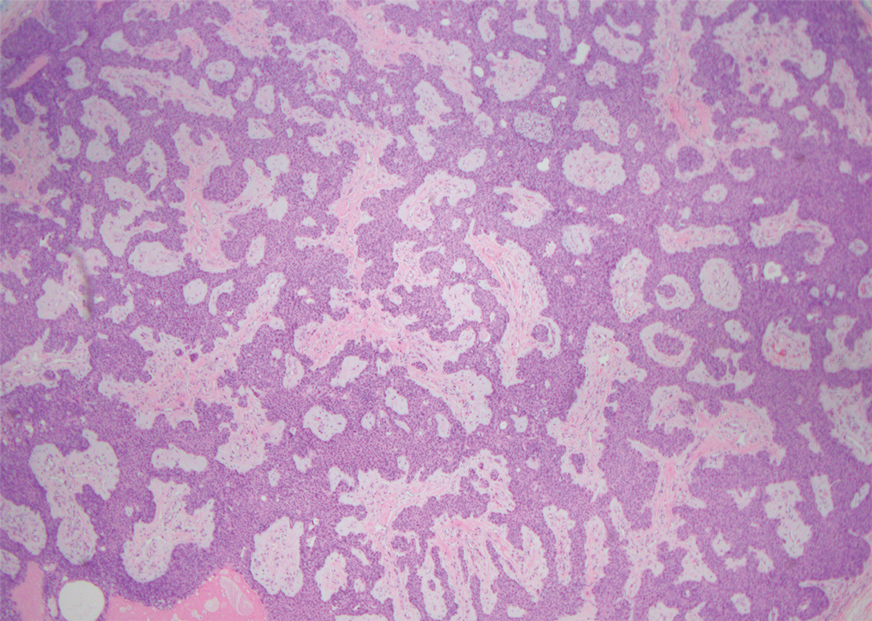

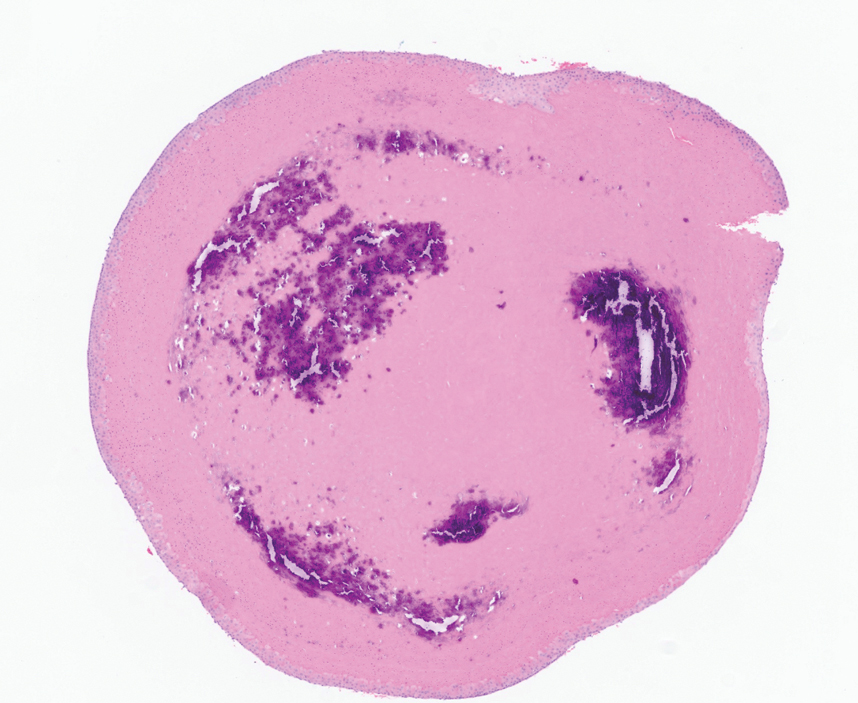

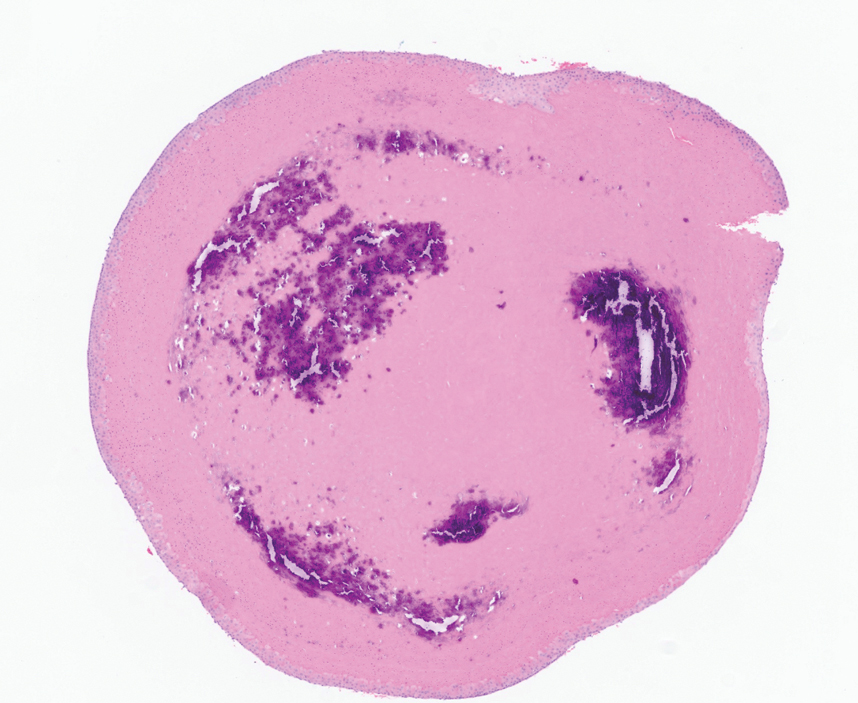

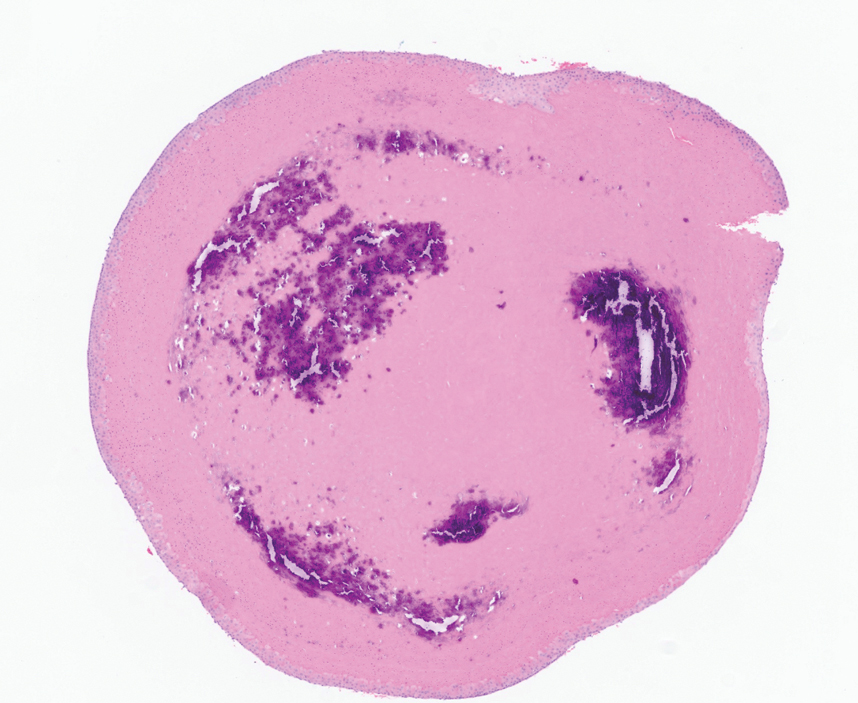

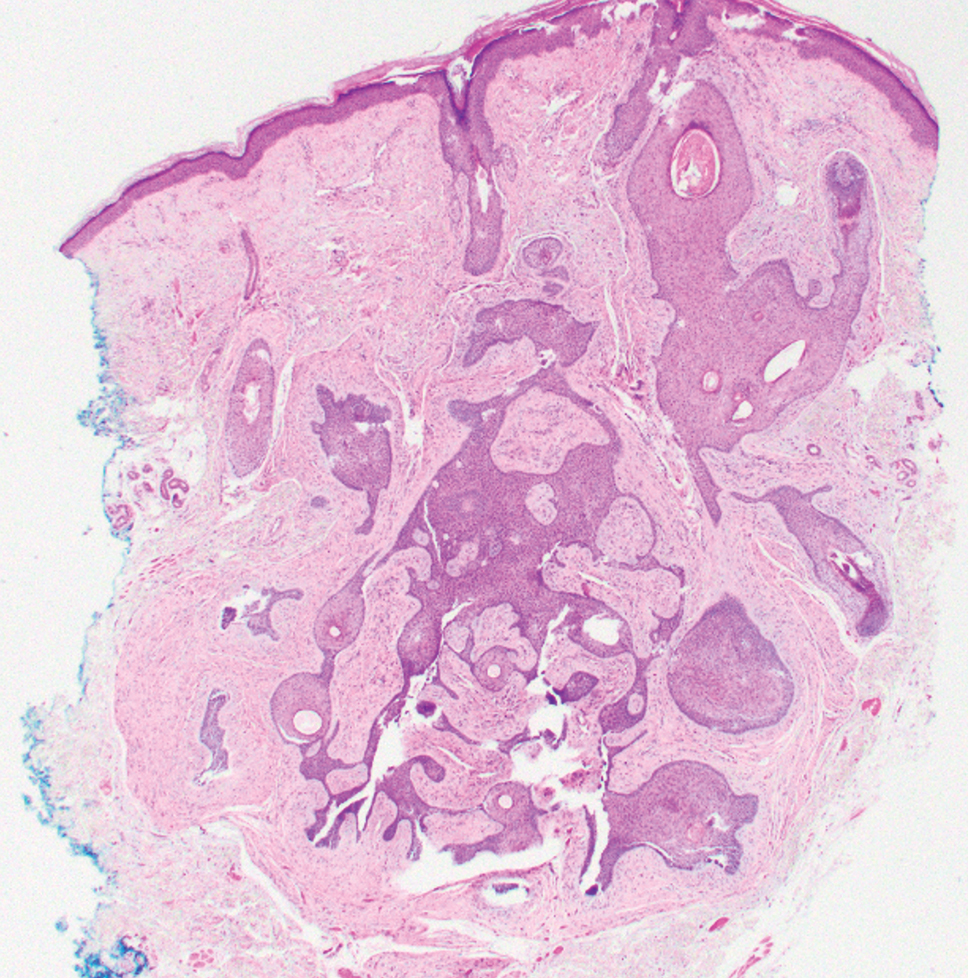

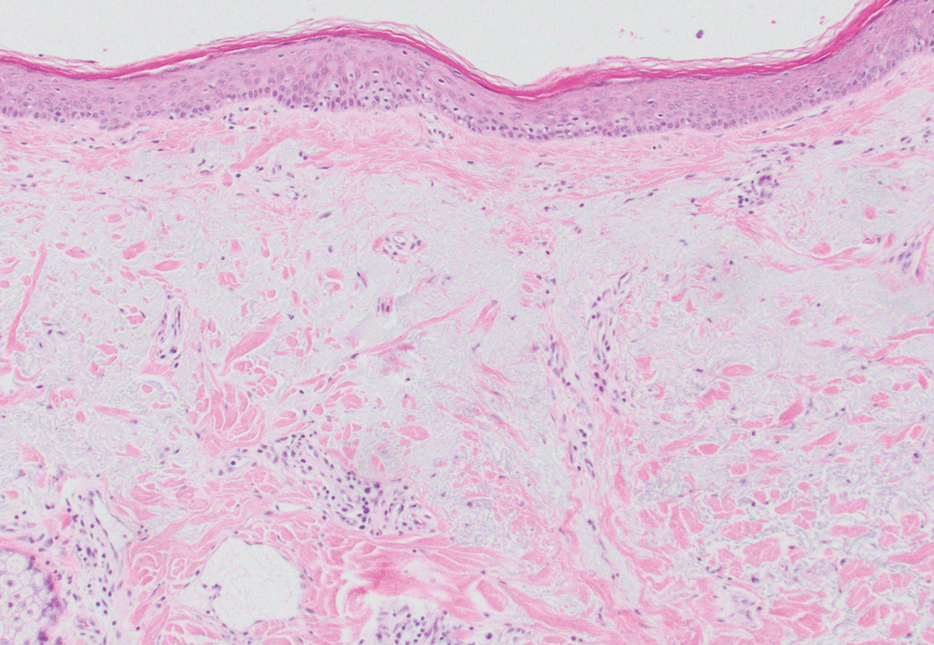

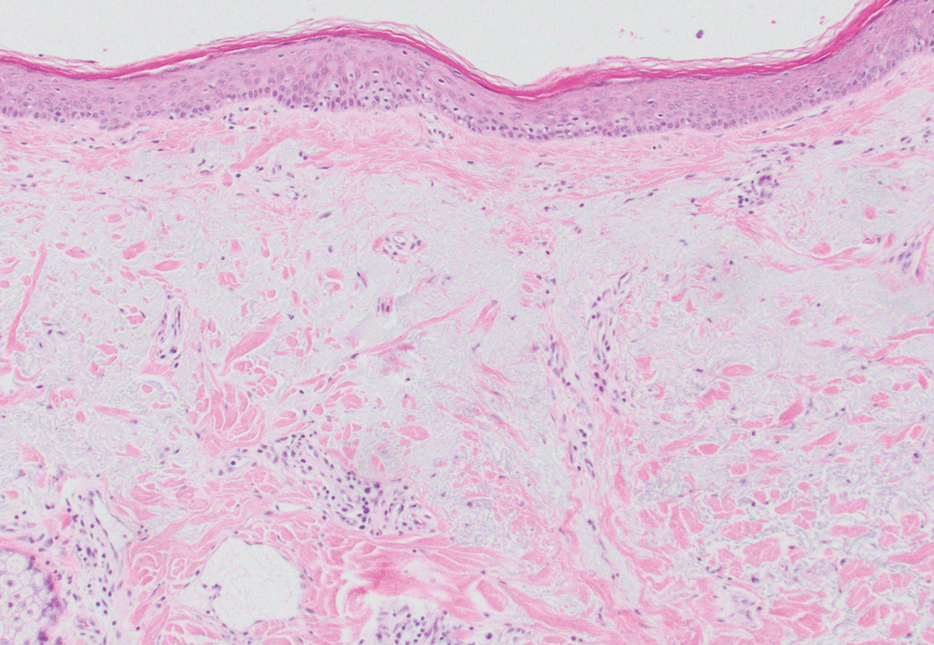

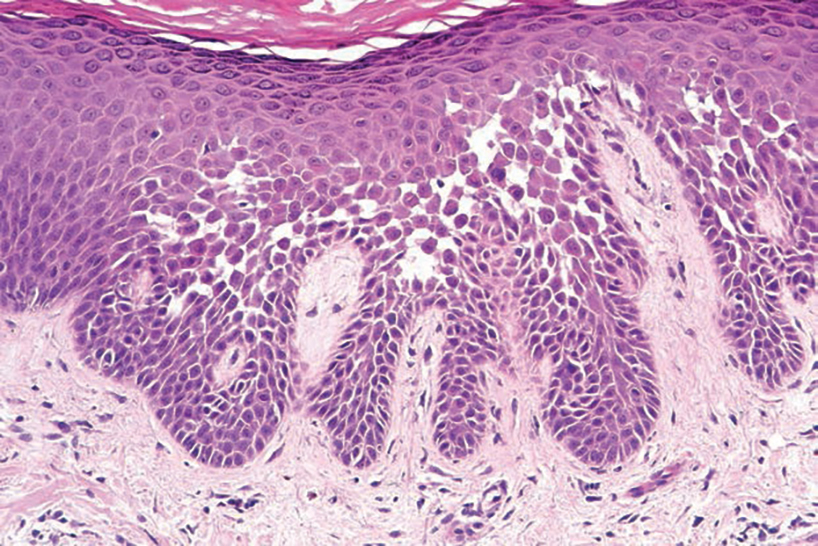

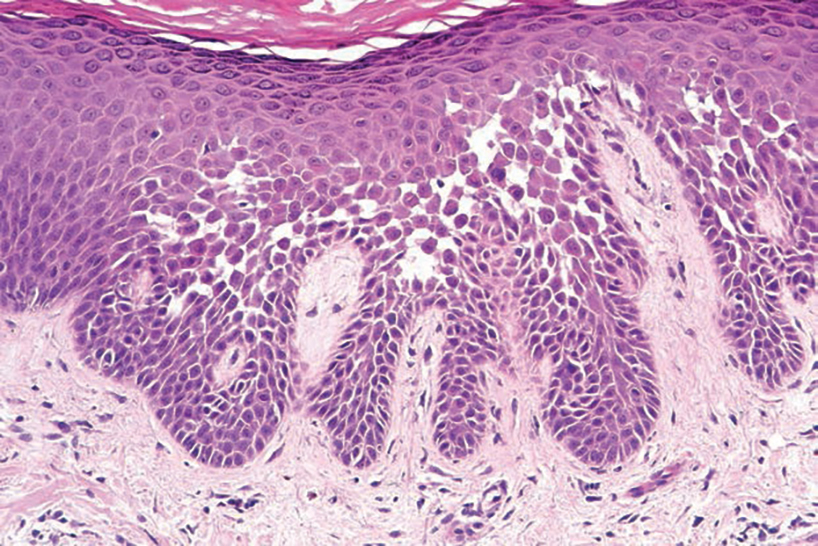

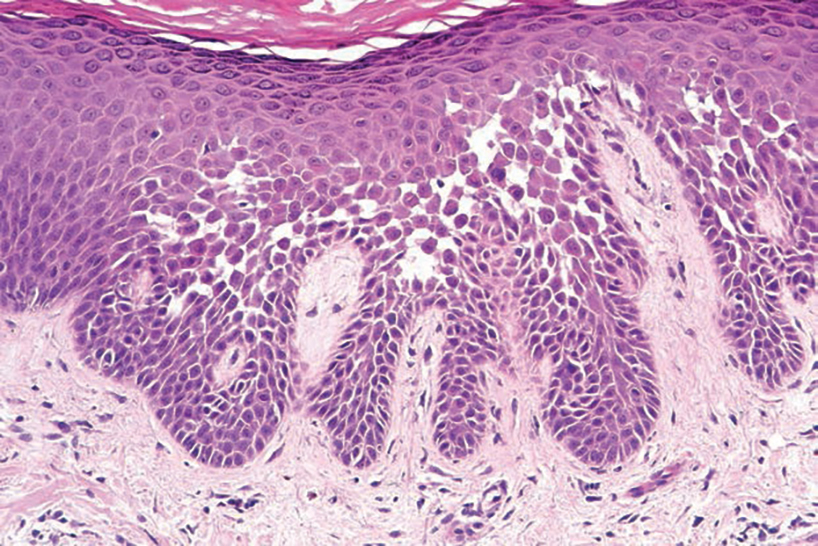

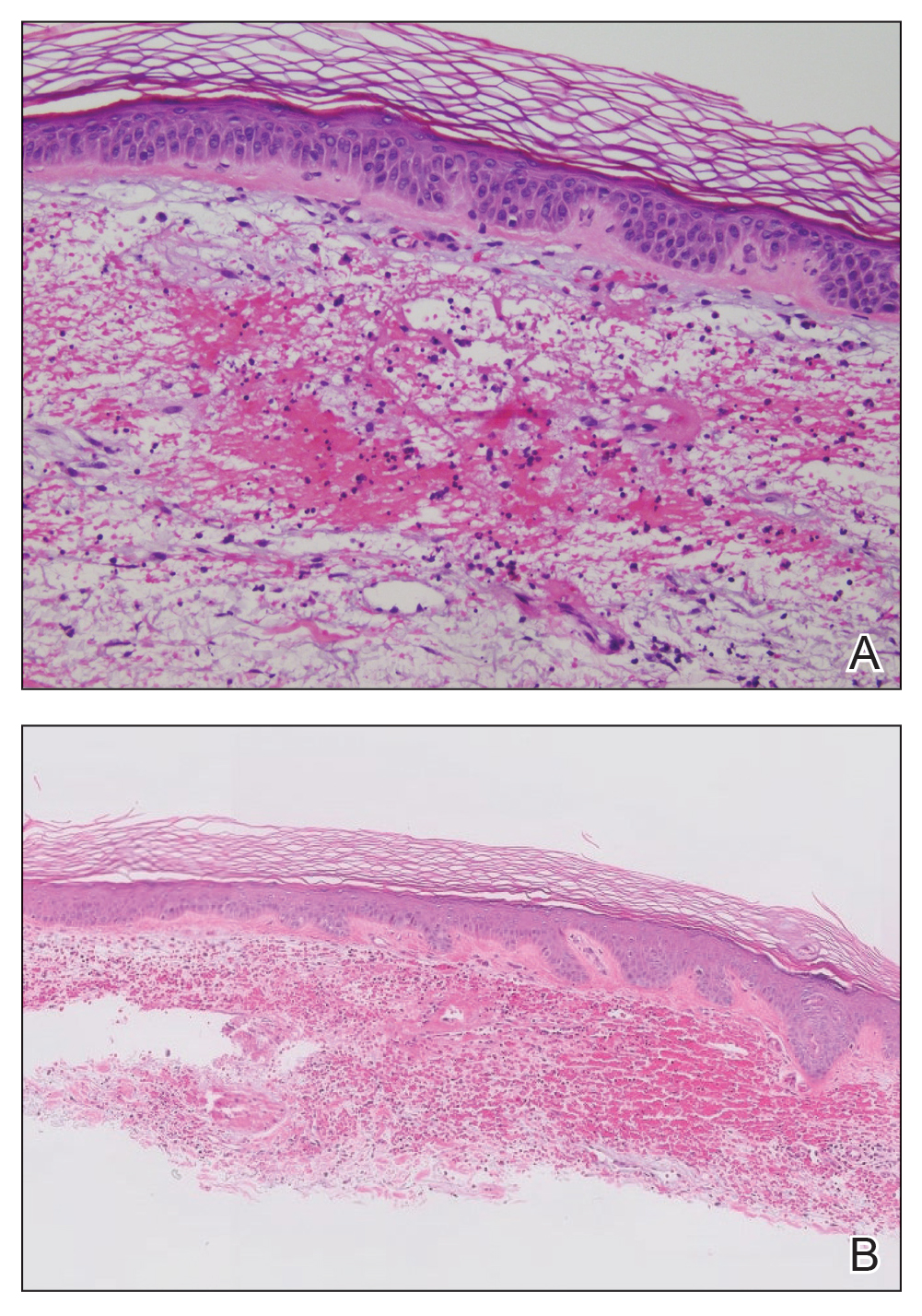

Nodular hidradenoma often manifests as a solitary nodule in the head or neck region, predominantly in women.7 Pathology shows well-demarcated intradermal aggregates of tumor cells within a hyalinized stroma; connection to the epidermis is not a feature of nodular hidradenoma. The epithelial component consists of polygonal cells with eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm as well as large glycogenated cells with pale to clear cytoplasm (leading to the alternative term clear cell hidradenoma)(Figure 3). The cystic portion represents deterioration of tumor cells. Surgical excision usually is curative, although lesions may recur. Malignant transformation is rare.7

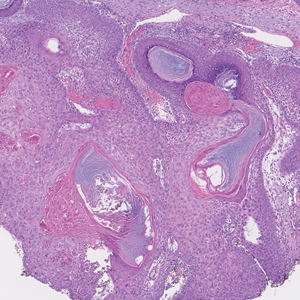

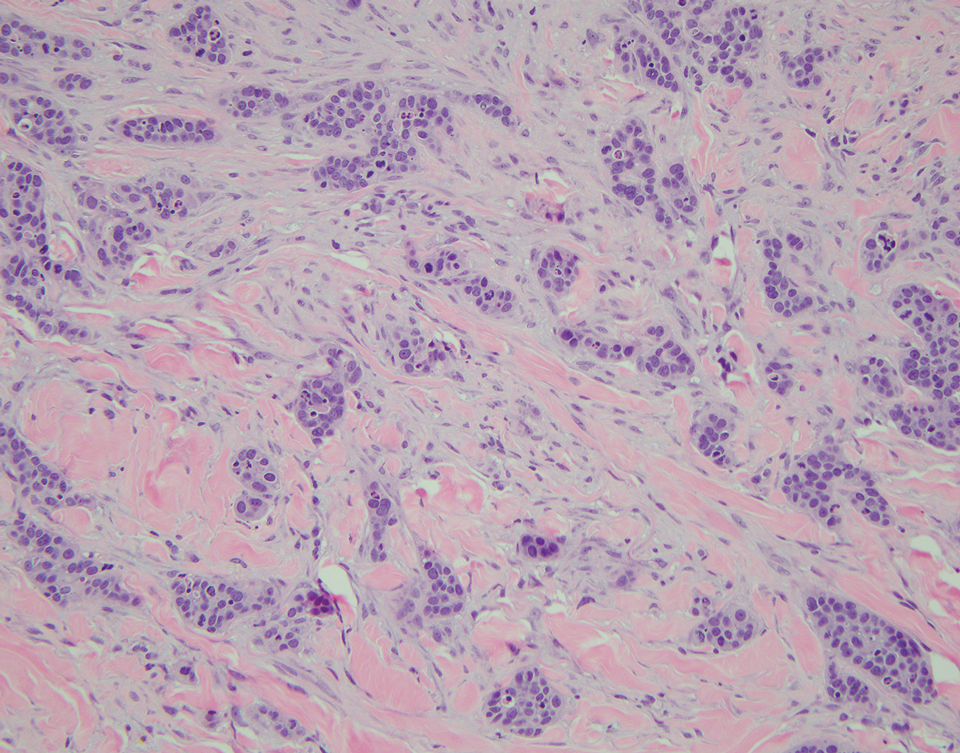

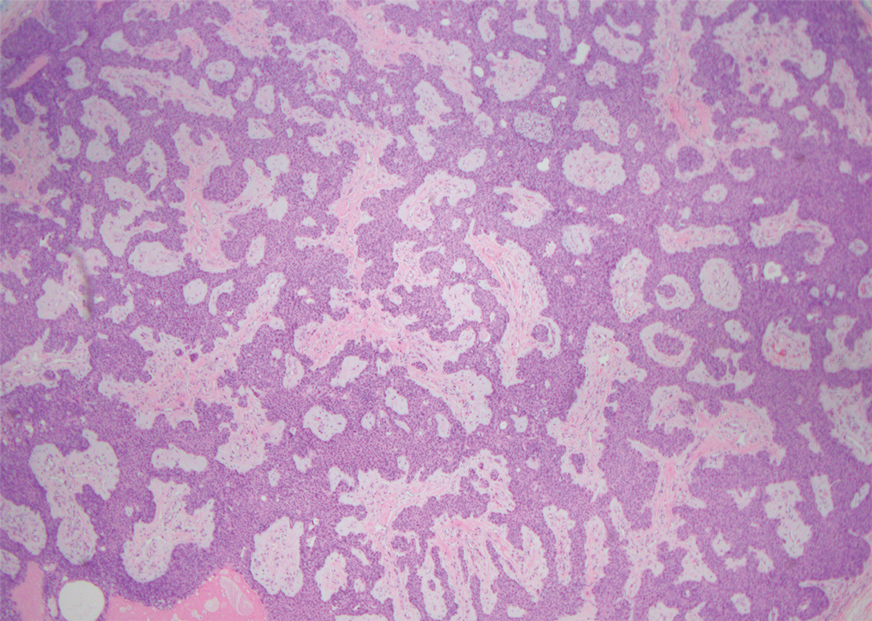

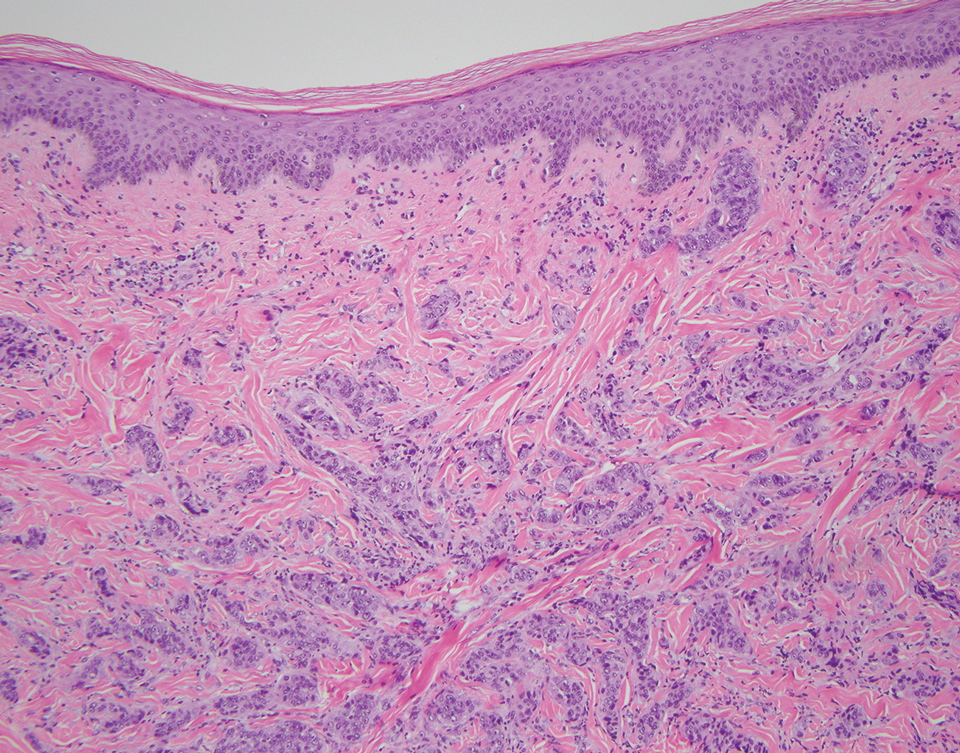

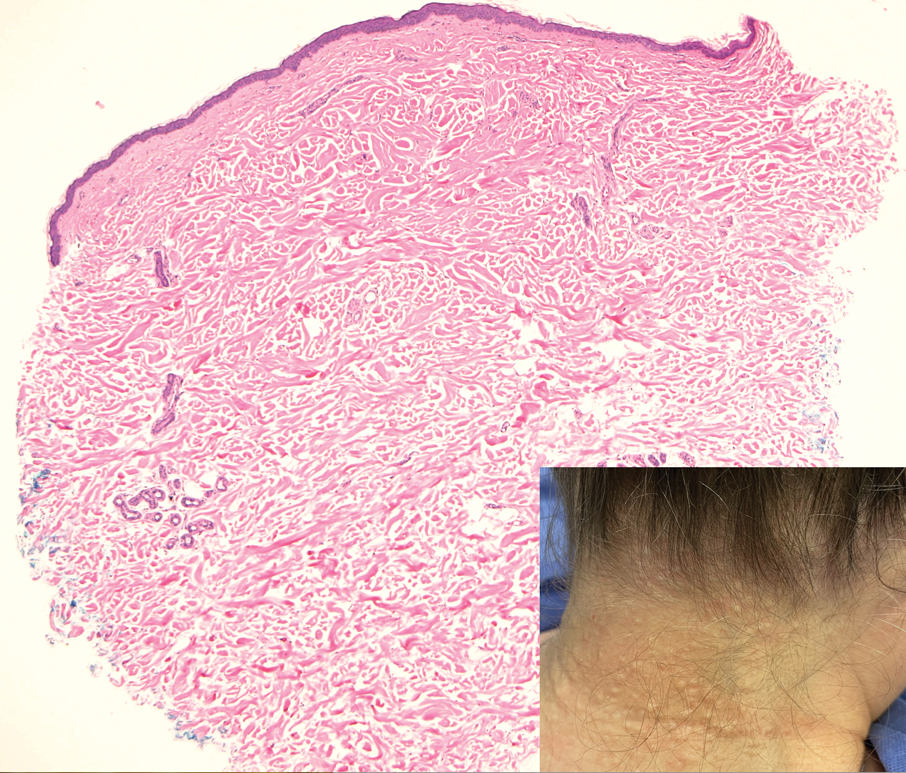

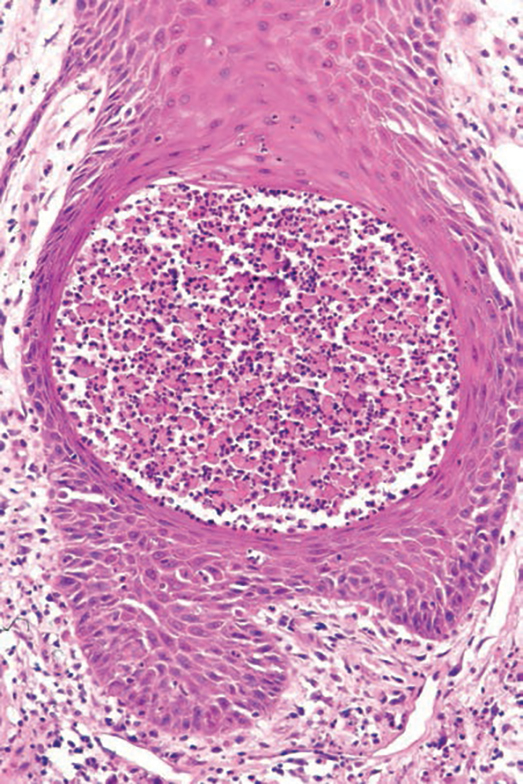

Sister Mary Joseph nodule is a cutaneous involvement of the umbilicus by a metastatic malignancy, often from an intra-abdominal primary malignancy (most commonly ovarian carcinoma in women and colonic carcinoma in men). Clinically, patients present with a solitary firm nodule or plaque within the umbilicus.8,9 Histopathology recapitulates the primary tumor (Figure 4).9 Sister Mary Joseph nodule portends a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of less than 8 months from the time of diagnosis.10

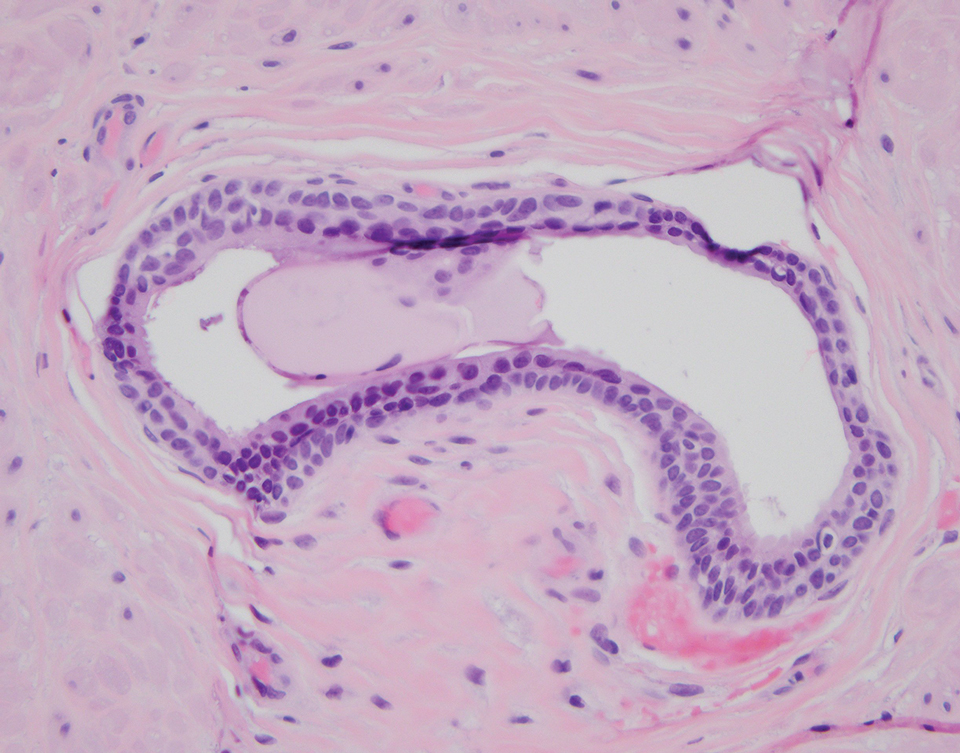

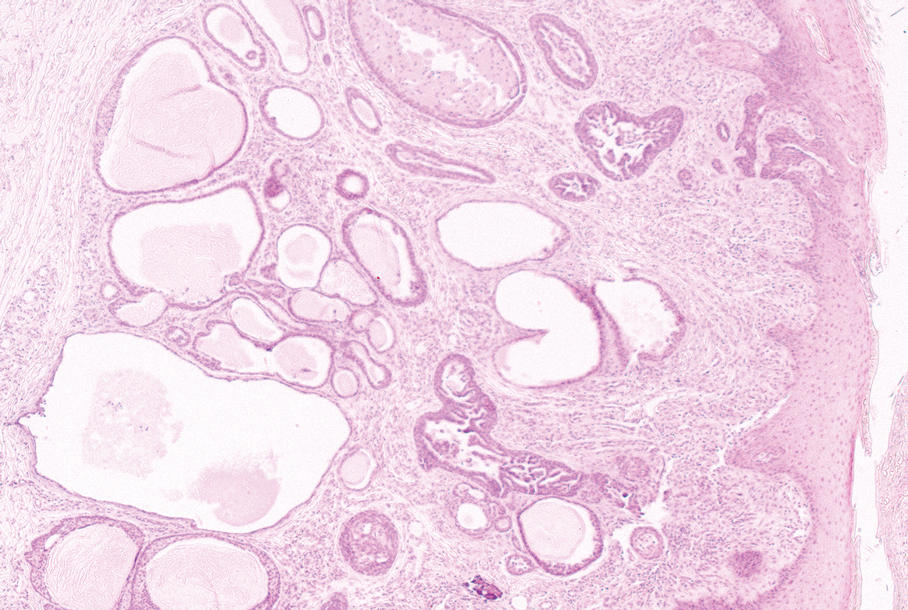

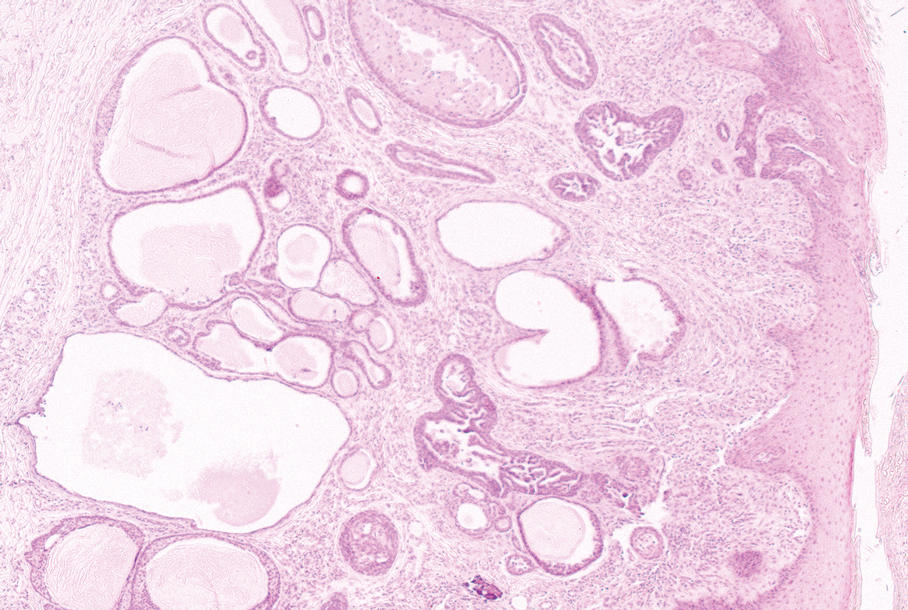

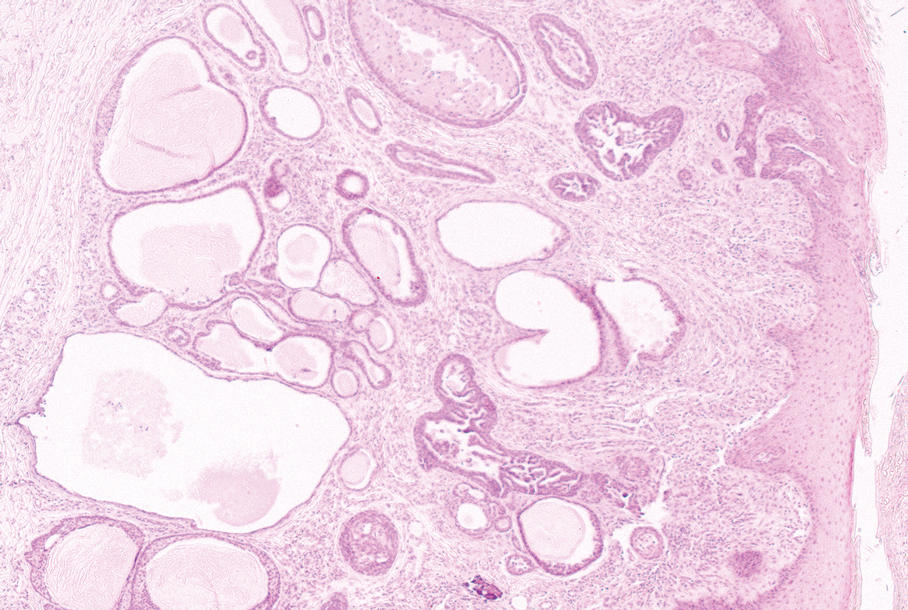

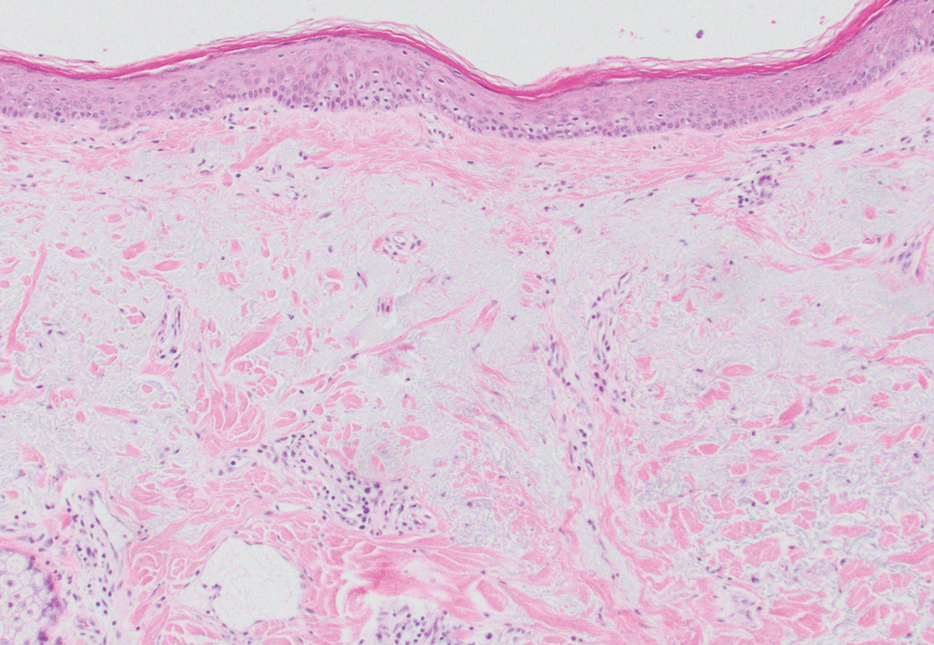

Urachal duct cyst develops from a remnant of the urachus that closed appropriately at the umbilicus and bladder but did not completely regress. It may manifest as an extraperitoneal mass at the umbilicus. Clinically, urachal duct cysts may be asymptomatic until an inciting event (eg, inflammation, deposition of calculus, or malignancy) occurs.11 Histopathology shows cystically dilated structures lined with a transitional epithelium (Figure 5).12 Urachal duct cysts usually are diagnosed in children or young adults and subsequently are excised.11

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the ectopic presence of endometrial tissue and occurs in approximately 13% of women of childbearing age.1 This non-neoplastic lesion can manifest on the skin in less than 5.5% of endometriosis cases worldwide. Historically, secondary cutaneous endometriosis (CE) most frequently has been associated with prior gynecologic surgery (often cesarean section)2; however, an increased incidence of primary CE in patients without prior surgical history recently has been documented in the literature.3 While secondary CE usually manifests at the site of a surgical scar, primary CE has a predilection for the umbilicus (Villar nodule). In both primary and secondary CE, patients present clinically with a solitary nodule and abdominal pain that may be exacerbated during menstruation. Bleeding without associated pain may be more common in primary CE, while bleeding with pain may be more common in secondary CE. Cutaneous endometriosis often is overlooked given its low incidence, leading to delayed diagnosis. Primary CE often is misdiagnosed clinically as a pyogenic granuloma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, or keloid, while secondary CE may be mistaken for a fibroma, incisional hernia, or granuloma.2

Primary and secondary CE have identical histopathologic features. Glands of variable size consisting of a single epithelial layer of columnar cells are present in the reticular dermis or subcutis (quiz image).4 The accompanying periglandular stroma often is uniform, consisting of spindle-shaped basophilic cells with abundant vascular structures. The stroma may contain moderate numbers of mitotic figures, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and extravasated red blood cells. The ectopic tissue may be inactive or display morphologic changes resembling those of the endometrium in the normal menstrual cycle.4 As the ectopic tissue progresses through the stages of menstruation, the glandular morphology also transforms. The proliferative stage demonstrates increased epithelial mitotic figures, the secretory stage exhibits intraluminal secretion, and during menstruation there are degenerative epithelial cells and evidence of vascular congestion. A mixture of glandular stages may be seen in biopsy results. Robust immunohistochemical expression of CD10 in the endometrial stroma can aid in diagnosis (Figure 1). Estrogen and progesterone receptor immunostaining also shows strong nuclear positivity, except in decidualized tissue.4 Unlike intestinal glands, endometrial glands do not express CDX2 or CK20.5 Complete surgical excision of CE usually is curative; however, recurrence has been documented in 10% (3/30) of cases.2

Breast carcinoma is the most common internal malignancy associated with cutaneous metastasis and may develop prior to visceral diagnosis. It is possible that tumor cells travel through the communicating networks of the cutaneous lymphatic ducts and the mammary lymphatic plexus; however, cutaneous manifestation often is located on the ipsilateral breast, and therefore tumor expansion rather than true metastasis cannot always be ruled out. On histopathology, findings of breast adenocarcinoma include tumor cells that tend to show either interstitial, nodular, mixed, or intravascular growth patterns (Figure 2). Tumor cells may invade the stroma in clusters or as individual cells. Sites of distant metastasis may show an increased likelihood of vascular and lymphatic invasion.6

Nodular hidradenoma often manifests as a solitary nodule in the head or neck region, predominantly in women.7 Pathology shows well-demarcated intradermal aggregates of tumor cells within a hyalinized stroma; connection to the epidermis is not a feature of nodular hidradenoma. The epithelial component consists of polygonal cells with eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm as well as large glycogenated cells with pale to clear cytoplasm (leading to the alternative term clear cell hidradenoma)(Figure 3). The cystic portion represents deterioration of tumor cells. Surgical excision usually is curative, although lesions may recur. Malignant transformation is rare.7

Sister Mary Joseph nodule is a cutaneous involvement of the umbilicus by a metastatic malignancy, often from an intra-abdominal primary malignancy (most commonly ovarian carcinoma in women and colonic carcinoma in men). Clinically, patients present with a solitary firm nodule or plaque within the umbilicus.8,9 Histopathology recapitulates the primary tumor (Figure 4).9 Sister Mary Joseph nodule portends a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of less than 8 months from the time of diagnosis.10

Urachal duct cyst develops from a remnant of the urachus that closed appropriately at the umbilicus and bladder but did not completely regress. It may manifest as an extraperitoneal mass at the umbilicus. Clinically, urachal duct cysts may be asymptomatic until an inciting event (eg, inflammation, deposition of calculus, or malignancy) occurs.11 Histopathology shows cystically dilated structures lined with a transitional epithelium (Figure 5).12 Urachal duct cysts usually are diagnosed in children or young adults and subsequently are excised.11

- Harder C, Velho RV, Brandes I, et al. Assessing the true prevalence of endometriosis: a narrative review of literature data. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;167:883-900. doi:10.1002/ijgo.15756

- Lopez-Soto A, Sanchez-Zapata MI, Martinez-Cendan JP, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: presentation of 33 cases and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Feb 2018;221:58-63. doi:10.1016 /j.ejogrb.2017.11.024

- Dridi D, Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, et al. Umbilical endometriosis: a systematic literature review and pathogenic theory proposal. J Clin Med. 2022;11:995. doi:10.3390/jcm11040995

- Farooq U, Laureano AC, Miteva M, Elgart GW. Cutaneous endometriosis: diagnostic immunohistochemistry and clinicopathologic correlation. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:525-528. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01681.x

- Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Endometriosis-associated extraovarian malignancies: a challenging question for the clinician and the pathologist. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2429-2438. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14212

- Ronen S, Suster D, Chen WS, et al. Histologic patterns of cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 232 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:401-411. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001841

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31821a4d33

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181954187

- Powell FC, Cooper AJ, Massa MC, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: a clinical and histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:610-615. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80265-0

- Hugen N, Kanne H, Simmer F, et al. Umbilical metastases: real-world data shows abysmal outcome. Int J Cancer. 2021;149: 1266-1273. doi:10.1002/ijc.33684

- Al-Salem A. An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology. 1st ed. Springer Cham; 2016.

- Schubert GE, Pavkovic MB, Bethke-Bedürftig BA. Tubular urachal remnants in adult bladders. J Urol. 1982;127:40-42. doi:10.1016/s0022- 5347(17)53595-8

- Harder C, Velho RV, Brandes I, et al. Assessing the true prevalence of endometriosis: a narrative review of literature data. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;167:883-900. doi:10.1002/ijgo.15756

- Lopez-Soto A, Sanchez-Zapata MI, Martinez-Cendan JP, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: presentation of 33 cases and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Feb 2018;221:58-63. doi:10.1016 /j.ejogrb.2017.11.024

- Dridi D, Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, et al. Umbilical endometriosis: a systematic literature review and pathogenic theory proposal. J Clin Med. 2022;11:995. doi:10.3390/jcm11040995

- Farooq U, Laureano AC, Miteva M, Elgart GW. Cutaneous endometriosis: diagnostic immunohistochemistry and clinicopathologic correlation. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:525-528. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01681.x

- Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Endometriosis-associated extraovarian malignancies: a challenging question for the clinician and the pathologist. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2429-2438. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14212

- Ronen S, Suster D, Chen WS, et al. Histologic patterns of cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 232 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:401-411. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001841

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31821a4d33

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181954187

- Powell FC, Cooper AJ, Massa MC, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: a clinical and histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:610-615. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80265-0

- Hugen N, Kanne H, Simmer F, et al. Umbilical metastases: real-world data shows abysmal outcome. Int J Cancer. 2021;149: 1266-1273. doi:10.1002/ijc.33684

- Al-Salem A. An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology. 1st ed. Springer Cham; 2016.

- Schubert GE, Pavkovic MB, Bethke-Bedürftig BA. Tubular urachal remnants in adult bladders. J Urol. 1982;127:40-42. doi:10.1016/s0022- 5347(17)53595-8

Solitary Lesion on the Umbilicus

Solitary Lesion on the Umbilicus

A 33-year-old woman with no notable medical or surgical history presented to our clinic with a solitary indurated nodule on the umbilicus that had been progressively enlarging for 1 year. The patient reported that she had undergone piercing of the umbilicus more than 5 years prior. She noted that the lesion was uncomfortable and pruritic and occasionally bled spontaneously. Physical examination revealed no other mucosal or cutaneous findings. A shave biopsy of the nodule was performed.

Alpha-Gal Syndrome: 5 Things to Know

Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), a tickborne disease commonly called “red meat allergy,” is a serious, potentially life-threatening allergy to the carbohydrate alpha-gal. The alpha-gal carbohydrate is found in most mammals, though it is not in humans, apes, or old-world monkeys. People with AGS can have allergic reactions when they consume mammalian meat, dairy products, or other products derived from mammals. People often live with this disease for years before receiving a correct diagnosis, greatly impacting their quality of life. The number of suspected cases is also rising.

More than 110,000 suspected AGS cases were identified between 2010 and 2022, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report.1 However, because the diagnosis requires a positive test and a clinical exam and some people may not get tested, as many as 450,000 people might be affected by AGS in the United States. Additionally, a CDC survey found that nearly half (42%) of US healthcare providers had never heard of AGS.2 Among those who had, less than one third (29%) knew how to diagnose the condition.

Here are 5 things clinicians need to know about AGS.

1. People can develop AGS after being bitten by a tick, primarily the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), in the United States.

In the United States, AGS is primarily associated with the bite of a lone star tick, but other kinds of ticks have not been ruled out. The majority of suspected AGS cases in the United States were reported in parts of Arkansas, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia. The lone star tick is widely distributed with established populations in Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

While AGS is associated with tick bites, more research is needed to understand the role ticks play in starting this condition, and why certain people develop AGS. Anyone can develop AGS, but most cases have been reported in adults.

Know how to recognize the symptoms of AGS and be prepared to test, diagnose, and manage AGS, particularly in states where lone star ticks are found.

2. Tick bites are only one risk factor for developing AGS.

Many people are bitten by lone star ticks and will never develop AGS. Scientists are exploring the connection between other risk factors and developing AGS. A recent study has shown that people diagnosed with AGS may be more likely to have a family member who was also diagnosed with AGS, have another food allergy, have an allergy to stinging or biting insects, or have A or O blood types.3

Research has also shown that environmental risk factors could contribute to developing AGS,4 like living in an area with lone star ticks, remembering finding a tick on themselves, recalling multiple tick bites, living near a wooded forest, spending more time outside, or living in areas with deer, such as larger properties, wooded forests, and properties with shrubs and brush.

Ask your patient questions about other allergies and history of recent tick bites or outdoor exposure to help determine if testing for AGS is appropriate.

3. Symptoms of AGS are consistently inconsistent.

There is a spectrum of how sensitive AGS patients are to alpha-gal, and reactions are often different from person to person, which can make it difficult to diagnose. The first allergic reaction to AGS typically occurs between 1-6 months after a tick bite. Symptoms commonly appear 2-6 hours after being in contact with products containing alpha-gal, like red meat (beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, or other meat from mammals), dairy, and some medications. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and include hives or itchy rash; swelling of the lips, throat, tongue, or eyelids; gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea; heartburn or indigestion; cough, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing; dizziness or a drop in blood pressure; or anaphylaxis.

Consider AGS if a patient reports waking up in the middle of the night with allergic symptoms after eating alpha-gal containing products for dinner, if allergic reactions are delayed, or if a patient has anaphylaxis of unknown cause, adult-onset allergy, or allergic symptoms and reports a recent tick bite.

4. Diagnosing AGS requires a combination of a blood test and a physical exam.

Diagnosing AGS requires a detailed patient history, physical exam, and a blood test to detect specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies specific to alpha-gal (alpha-gal sIgE). Tests for alpha-gal sIgE antibodies are available at several large commercial laboratories and some academic institutions. Skin tests to identify reactions to allergens like pork or beef may also be used to inform AGS diagnosis. However, a positive alpha-gal sIgE test or skin test does not mean a person has AGS. Many people, particularly those who live in regions with lone star ticks, have positive alpha-gal specific IgE tests without having AGS.

Consider the test results along with your patient’s symptoms and risk factors.

5. There is no treatment for AGS, but people can take prevention steps and AGS can be managed.

People can protect themselves and their family from AGS by preventing tick bites. Encourage your patients to use an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent outdoors, wear permethrin-treated clothing, and conduct thorough tick checks after outdoor activities.

Once a person is no longer exposed to alpha-gal containing products, they should no longer experience symptoms. People with AGS should also proactively prevent tick bites. Tick bites can trigger or reactivate AGS.

For patients who have AGS, help manage their symptoms and identify alpha-gal containing products to avoid.

Dr. Kersh is Chief of the Rickettsial Zoonoses Branch, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, and disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

CDC resources:

About Alpha-gal Syndrome | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Alpha-gal Syndrome | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

Clinical Resources | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

References

Thompson JM et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:815-820.

Carpenter A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:809-814. Taylor ML et al. Ann Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2024 Jun;132(6):759.e2-764.e2. Kersh GJ et al. Ann Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2023 Apr;130(4):472-478.

Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), a tickborne disease commonly called “red meat allergy,” is a serious, potentially life-threatening allergy to the carbohydrate alpha-gal. The alpha-gal carbohydrate is found in most mammals, though it is not in humans, apes, or old-world monkeys. People with AGS can have allergic reactions when they consume mammalian meat, dairy products, or other products derived from mammals. People often live with this disease for years before receiving a correct diagnosis, greatly impacting their quality of life. The number of suspected cases is also rising.

More than 110,000 suspected AGS cases were identified between 2010 and 2022, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report.1 However, because the diagnosis requires a positive test and a clinical exam and some people may not get tested, as many as 450,000 people might be affected by AGS in the United States. Additionally, a CDC survey found that nearly half (42%) of US healthcare providers had never heard of AGS.2 Among those who had, less than one third (29%) knew how to diagnose the condition.

Here are 5 things clinicians need to know about AGS.

1. People can develop AGS after being bitten by a tick, primarily the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), in the United States.

In the United States, AGS is primarily associated with the bite of a lone star tick, but other kinds of ticks have not been ruled out. The majority of suspected AGS cases in the United States were reported in parts of Arkansas, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia. The lone star tick is widely distributed with established populations in Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

While AGS is associated with tick bites, more research is needed to understand the role ticks play in starting this condition, and why certain people develop AGS. Anyone can develop AGS, but most cases have been reported in adults.

Know how to recognize the symptoms of AGS and be prepared to test, diagnose, and manage AGS, particularly in states where lone star ticks are found.

2. Tick bites are only one risk factor for developing AGS.

Many people are bitten by lone star ticks and will never develop AGS. Scientists are exploring the connection between other risk factors and developing AGS. A recent study has shown that people diagnosed with AGS may be more likely to have a family member who was also diagnosed with AGS, have another food allergy, have an allergy to stinging or biting insects, or have A or O blood types.3

Research has also shown that environmental risk factors could contribute to developing AGS,4 like living in an area with lone star ticks, remembering finding a tick on themselves, recalling multiple tick bites, living near a wooded forest, spending more time outside, or living in areas with deer, such as larger properties, wooded forests, and properties with shrubs and brush.

Ask your patient questions about other allergies and history of recent tick bites or outdoor exposure to help determine if testing for AGS is appropriate.

3. Symptoms of AGS are consistently inconsistent.

There is a spectrum of how sensitive AGS patients are to alpha-gal, and reactions are often different from person to person, which can make it difficult to diagnose. The first allergic reaction to AGS typically occurs between 1-6 months after a tick bite. Symptoms commonly appear 2-6 hours after being in contact with products containing alpha-gal, like red meat (beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, or other meat from mammals), dairy, and some medications. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and include hives or itchy rash; swelling of the lips, throat, tongue, or eyelids; gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea; heartburn or indigestion; cough, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing; dizziness or a drop in blood pressure; or anaphylaxis.

Consider AGS if a patient reports waking up in the middle of the night with allergic symptoms after eating alpha-gal containing products for dinner, if allergic reactions are delayed, or if a patient has anaphylaxis of unknown cause, adult-onset allergy, or allergic symptoms and reports a recent tick bite.

4. Diagnosing AGS requires a combination of a blood test and a physical exam.

Diagnosing AGS requires a detailed patient history, physical exam, and a blood test to detect specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies specific to alpha-gal (alpha-gal sIgE). Tests for alpha-gal sIgE antibodies are available at several large commercial laboratories and some academic institutions. Skin tests to identify reactions to allergens like pork or beef may also be used to inform AGS diagnosis. However, a positive alpha-gal sIgE test or skin test does not mean a person has AGS. Many people, particularly those who live in regions with lone star ticks, have positive alpha-gal specific IgE tests without having AGS.

Consider the test results along with your patient’s symptoms and risk factors.

5. There is no treatment for AGS, but people can take prevention steps and AGS can be managed.

People can protect themselves and their family from AGS by preventing tick bites. Encourage your patients to use an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent outdoors, wear permethrin-treated clothing, and conduct thorough tick checks after outdoor activities.

Once a person is no longer exposed to alpha-gal containing products, they should no longer experience symptoms. People with AGS should also proactively prevent tick bites. Tick bites can trigger or reactivate AGS.

For patients who have AGS, help manage their symptoms and identify alpha-gal containing products to avoid.

Dr. Kersh is Chief of the Rickettsial Zoonoses Branch, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, and disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

CDC resources:

About Alpha-gal Syndrome | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Alpha-gal Syndrome | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

Clinical Resources | Alpha-gal Syndrome | CDC

References

Thompson JM et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:815-820.

Carpenter A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:809-814. Taylor ML et al. Ann Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2024 Jun;132(6):759.e2-764.e2. Kersh GJ et al. Ann Allergy, Asthma & Immunol. 2023 Apr;130(4):472-478.

Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), a tickborne disease commonly called “red meat allergy,” is a serious, potentially life-threatening allergy to the carbohydrate alpha-gal. The alpha-gal carbohydrate is found in most mammals, though it is not in humans, apes, or old-world monkeys. People with AGS can have allergic reactions when they consume mammalian meat, dairy products, or other products derived from mammals. People often live with this disease for years before receiving a correct diagnosis, greatly impacting their quality of life. The number of suspected cases is also rising.

More than 110,000 suspected AGS cases were identified between 2010 and 2022, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report.1 However, because the diagnosis requires a positive test and a clinical exam and some people may not get tested, as many as 450,000 people might be affected by AGS in the United States. Additionally, a CDC survey found that nearly half (42%) of US healthcare providers had never heard of AGS.2 Among those who had, less than one third (29%) knew how to diagnose the condition.

Here are 5 things clinicians need to know about AGS.

1. People can develop AGS after being bitten by a tick, primarily the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), in the United States.

In the United States, AGS is primarily associated with the bite of a lone star tick, but other kinds of ticks have not been ruled out. The majority of suspected AGS cases in the United States were reported in parts of Arkansas, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia. The lone star tick is widely distributed with established populations in Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

While AGS is associated with tick bites, more research is needed to understand the role ticks play in starting this condition, and why certain people develop AGS. Anyone can develop AGS, but most cases have been reported in adults.

Know how to recognize the symptoms of AGS and be prepared to test, diagnose, and manage AGS, particularly in states where lone star ticks are found.

2. Tick bites are only one risk factor for developing AGS.

Many people are bitten by lone star ticks and will never develop AGS. Scientists are exploring the connection between other risk factors and developing AGS. A recent study has shown that people diagnosed with AGS may be more likely to have a family member who was also diagnosed with AGS, have another food allergy, have an allergy to stinging or biting insects, or have A or O blood types.3

Research has also shown that environmental risk factors could contribute to developing AGS,4 like living in an area with lone star ticks, remembering finding a tick on themselves, recalling multiple tick bites, living near a wooded forest, spending more time outside, or living in areas with deer, such as larger properties, wooded forests, and properties with shrubs and brush.

Ask your patient questions about other allergies and history of recent tick bites or outdoor exposure to help determine if testing for AGS is appropriate.