User login

Stump the Professor event entertains, educates

Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, joked that participating in a “Stump the Professor” event is “like taking an oral exam in front of 300 or 400 people.”

Dr. Dhaliwal passed his “exam” with flying colors on Wednesday at HM17, correctly making a diagnosis of a case of leptospirosis described by his co-presenter Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, professor of medicine and director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

While the format is intended to be fun and entertaining, he said that there is no doubt that learning is taking place – both by him and by the audience.

“The most important goal by far and away is to put our most important procedure on display, which is thinking,” he said. “We don’t always make our thinking explicit, and we don’t often open it to scrutiny. So the goal of this session is to do both.”

Talking through his uncertainty can be one of the most interesting aspects of the session, Dr. Dhaliwal told attendees.

“If I can’t say something insightful, let me try to capture my uncertainty and crystallize that for you so you recognize that as a real part of medicine,” he said.

The HM17 audience seemed to enjoy trying to solve the case and thinking through the clinical reasoning as Dr. Dhaliwal did the same. The diagnosis of leptospirosis in Wednesday’s case surprised the audience, many of whom shook their heads in amazement.

“I pick cases based on being dramatic and/or unusual enough to provide some clinical excitement and diagnostic challenge,” he said.

An “important bonus,” Dr. Dhaliwal said, is that the audience would learn something about the disease that’s being discussed.

“I suspect I learn the most, especially if I get the case wrong,” he told attendees. “After living it on stage, there’s a lot that I upload in my memory for the next time I see something like this in real life.”

He said he’s probably batting about 0.500 on getting the cases right.

“I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve pulled the rabbit out of the hat at the last minute, and it’s been glorious, and I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve fallen flat on my face, and I didn’t have a prayer of knowing it, either, because my thinking was off, my knowledge was deficient, or it was something I had never heard of before,” he said. “The one thing that’s always rewarding is that people are always very appreciative that I shared my thinking, whether it’s a flash of insight or a total stumble or an uncertainty that I have.”

It might seem that the event has more of a potential downside than upside: If he gets a case right, he’s doing what he should do; if he gets one wrong, it might be embarrassing. He doesn’t see it that way, he told the crowd.

“It’s a total joy to be up here,” Dr. Dhaliwal said. “There’s no doubt that standing in front of a crowd induces a little bit of anxiety, but it is a lot of fun to do. And I had mentors who did this, and then I started to learn it myself, and at some point, you get past the anxiety of being right or wrong, and you just enjoy being up there.”

Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, joked that participating in a “Stump the Professor” event is “like taking an oral exam in front of 300 or 400 people.”

Dr. Dhaliwal passed his “exam” with flying colors on Wednesday at HM17, correctly making a diagnosis of a case of leptospirosis described by his co-presenter Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, professor of medicine and director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

While the format is intended to be fun and entertaining, he said that there is no doubt that learning is taking place – both by him and by the audience.

“The most important goal by far and away is to put our most important procedure on display, which is thinking,” he said. “We don’t always make our thinking explicit, and we don’t often open it to scrutiny. So the goal of this session is to do both.”

Talking through his uncertainty can be one of the most interesting aspects of the session, Dr. Dhaliwal told attendees.

“If I can’t say something insightful, let me try to capture my uncertainty and crystallize that for you so you recognize that as a real part of medicine,” he said.

The HM17 audience seemed to enjoy trying to solve the case and thinking through the clinical reasoning as Dr. Dhaliwal did the same. The diagnosis of leptospirosis in Wednesday’s case surprised the audience, many of whom shook their heads in amazement.

“I pick cases based on being dramatic and/or unusual enough to provide some clinical excitement and diagnostic challenge,” he said.

An “important bonus,” Dr. Dhaliwal said, is that the audience would learn something about the disease that’s being discussed.

“I suspect I learn the most, especially if I get the case wrong,” he told attendees. “After living it on stage, there’s a lot that I upload in my memory for the next time I see something like this in real life.”

He said he’s probably batting about 0.500 on getting the cases right.

“I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve pulled the rabbit out of the hat at the last minute, and it’s been glorious, and I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve fallen flat on my face, and I didn’t have a prayer of knowing it, either, because my thinking was off, my knowledge was deficient, or it was something I had never heard of before,” he said. “The one thing that’s always rewarding is that people are always very appreciative that I shared my thinking, whether it’s a flash of insight or a total stumble or an uncertainty that I have.”

It might seem that the event has more of a potential downside than upside: If he gets a case right, he’s doing what he should do; if he gets one wrong, it might be embarrassing. He doesn’t see it that way, he told the crowd.

“It’s a total joy to be up here,” Dr. Dhaliwal said. “There’s no doubt that standing in front of a crowd induces a little bit of anxiety, but it is a lot of fun to do. And I had mentors who did this, and then I started to learn it myself, and at some point, you get past the anxiety of being right or wrong, and you just enjoy being up there.”

Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, joked that participating in a “Stump the Professor” event is “like taking an oral exam in front of 300 or 400 people.”

Dr. Dhaliwal passed his “exam” with flying colors on Wednesday at HM17, correctly making a diagnosis of a case of leptospirosis described by his co-presenter Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM, professor of medicine and director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

While the format is intended to be fun and entertaining, he said that there is no doubt that learning is taking place – both by him and by the audience.

“The most important goal by far and away is to put our most important procedure on display, which is thinking,” he said. “We don’t always make our thinking explicit, and we don’t often open it to scrutiny. So the goal of this session is to do both.”

Talking through his uncertainty can be one of the most interesting aspects of the session, Dr. Dhaliwal told attendees.

“If I can’t say something insightful, let me try to capture my uncertainty and crystallize that for you so you recognize that as a real part of medicine,” he said.

The HM17 audience seemed to enjoy trying to solve the case and thinking through the clinical reasoning as Dr. Dhaliwal did the same. The diagnosis of leptospirosis in Wednesday’s case surprised the audience, many of whom shook their heads in amazement.

“I pick cases based on being dramatic and/or unusual enough to provide some clinical excitement and diagnostic challenge,” he said.

An “important bonus,” Dr. Dhaliwal said, is that the audience would learn something about the disease that’s being discussed.

“I suspect I learn the most, especially if I get the case wrong,” he told attendees. “After living it on stage, there’s a lot that I upload in my memory for the next time I see something like this in real life.”

He said he’s probably batting about 0.500 on getting the cases right.

“I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve pulled the rabbit out of the hat at the last minute, and it’s been glorious, and I’ve had plenty of experiences where I’ve fallen flat on my face, and I didn’t have a prayer of knowing it, either, because my thinking was off, my knowledge was deficient, or it was something I had never heard of before,” he said. “The one thing that’s always rewarding is that people are always very appreciative that I shared my thinking, whether it’s a flash of insight or a total stumble or an uncertainty that I have.”

It might seem that the event has more of a potential downside than upside: If he gets a case right, he’s doing what he should do; if he gets one wrong, it might be embarrassing. He doesn’t see it that way, he told the crowd.

“It’s a total joy to be up here,” Dr. Dhaliwal said. “There’s no doubt that standing in front of a crowd induces a little bit of anxiety, but it is a lot of fun to do. And I had mentors who did this, and then I started to learn it myself, and at some point, you get past the anxiety of being right or wrong, and you just enjoy being up there.”

RIV winners celebrated for their creative use of data

This year’s RIV innovation winners reflect a nascent trend of applying informatics to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.

“One striking thing is that all three winners used either EHR or Big Data and large collaboratives to achieve their goals,” Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, and moderator of the winners’ panel, said in an interview. This year’s winners included a sleep-promoting “nudge” system that Dr. Fang said she expects will help improve sleep and lower rates of delirium and a source code that connects disparate data systems for daily updates on where quality can be improved. The third winner used what Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and the medical director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called a “classic quality improvement collaborative,” which simplifies the decision tree around venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis for better patient outcomes.

Calling uninterrupted sleep the “sine qua non” of patient care, RIV award recipient Vineet Arora, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, described the rationale for her RIV award-winning SIESTA (Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act) program. She and her colleagues surveyed hospitalists, nurses, residents, and patients to determine the most common sleep disrupters in their institution and devised “nudges” to alter how staff performed various tasks that otherwise might interfere with patient sleep. Rather than use overt incentives, nudges are changes in what Dr. Arora called the “choice architecture” of people’s behavior.

Based on survey feedback, Dr. Arora and her colleagues worked with their electronic health record (EHR) vendor to consolidate the performance of certain tasks that were affecting patient sleep. Reminders were added to daily nursing huddles to prompt them to look for ways they could decrease patient interruptions, and empowerment coaching was offered to nurses to encourage patient advocacy when physicians had given orders that would interfere with patients’ sleep.

When tested and measured over the course of a year, SIESTA’s EHR innovations resulted in six fewer nighttime disruptions than before the intervention, compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. The nursing-based interventions resulted in one less nocturnal interruption on average, also a significant change.

“If every patient were admitted into a SIESTA unit, 84% would say they were not disrupted by medications, compared to 57%. For interruptions for vitals, it would be 17% vs. 41%,” Dr. Arora said. In terms of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) data, this translates into as much as a 25th-percentile performance improvement for hospitals in related domains, according to Dr. Arora.

Nader Najafi, MD, an assistant clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, and his colleagues created Murmur, an open-source code data aggregator, which can be customized to solve a variety of quality improvement issues. RIV award winner Dr. Najafi applied the code to determine how systems failures in their institution were contributing to avoidable inpatient days, for example. At a daily appointed time, Murmur would determine which staff members were scheduled to work that day. Each provider would then receive a brief, customized survey about patients for that day on their cell phone. The data were then collected to create instant reports of where the delays in discharge were occurring.

Testing by gastroenterologists was pinpointed as a “huge source of delays, something we had never been able to quantify before, “ Dr. Najafi said. This led to brainstorming sessions with the department for solutions.

To reduce rates of hospital-associated VTE, 35 California hospitals with varying numbers of beds and locations collaborated on a project led by RIV award recipient Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. Key components of the intervention were mentoring at the sites by VTE prophylaxis experts, group webinars in best practices, and a “measure-vention.” Teams were taught how to rate patient risk for VTE and apply specific protocols according to risk rating using the SHM-mentored implementation model. Real-time monitoring of the intervention was used to make any necessary adjustments. When before-and-after data were compared, following the 18-month period during which the intervention was measured, Dr. Jenkins said an average of 330 VTEs were averted annually. “We found the results very gratifying,” said Dr. Jenkins.

“These projects all reflect a broader trend in hospital medicine where we are using the wealth of data we have now for quality improvement and for outcomes research,” Dr. Fang said in the interview.

There were no relevant disclosures.

This year’s RIV innovation winners reflect a nascent trend of applying informatics to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.

“One striking thing is that all three winners used either EHR or Big Data and large collaboratives to achieve their goals,” Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, and moderator of the winners’ panel, said in an interview. This year’s winners included a sleep-promoting “nudge” system that Dr. Fang said she expects will help improve sleep and lower rates of delirium and a source code that connects disparate data systems for daily updates on where quality can be improved. The third winner used what Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and the medical director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called a “classic quality improvement collaborative,” which simplifies the decision tree around venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis for better patient outcomes.

Calling uninterrupted sleep the “sine qua non” of patient care, RIV award recipient Vineet Arora, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, described the rationale for her RIV award-winning SIESTA (Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act) program. She and her colleagues surveyed hospitalists, nurses, residents, and patients to determine the most common sleep disrupters in their institution and devised “nudges” to alter how staff performed various tasks that otherwise might interfere with patient sleep. Rather than use overt incentives, nudges are changes in what Dr. Arora called the “choice architecture” of people’s behavior.

Based on survey feedback, Dr. Arora and her colleagues worked with their electronic health record (EHR) vendor to consolidate the performance of certain tasks that were affecting patient sleep. Reminders were added to daily nursing huddles to prompt them to look for ways they could decrease patient interruptions, and empowerment coaching was offered to nurses to encourage patient advocacy when physicians had given orders that would interfere with patients’ sleep.

When tested and measured over the course of a year, SIESTA’s EHR innovations resulted in six fewer nighttime disruptions than before the intervention, compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. The nursing-based interventions resulted in one less nocturnal interruption on average, also a significant change.

“If every patient were admitted into a SIESTA unit, 84% would say they were not disrupted by medications, compared to 57%. For interruptions for vitals, it would be 17% vs. 41%,” Dr. Arora said. In terms of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) data, this translates into as much as a 25th-percentile performance improvement for hospitals in related domains, according to Dr. Arora.

Nader Najafi, MD, an assistant clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, and his colleagues created Murmur, an open-source code data aggregator, which can be customized to solve a variety of quality improvement issues. RIV award winner Dr. Najafi applied the code to determine how systems failures in their institution were contributing to avoidable inpatient days, for example. At a daily appointed time, Murmur would determine which staff members were scheduled to work that day. Each provider would then receive a brief, customized survey about patients for that day on their cell phone. The data were then collected to create instant reports of where the delays in discharge were occurring.

Testing by gastroenterologists was pinpointed as a “huge source of delays, something we had never been able to quantify before, “ Dr. Najafi said. This led to brainstorming sessions with the department for solutions.

To reduce rates of hospital-associated VTE, 35 California hospitals with varying numbers of beds and locations collaborated on a project led by RIV award recipient Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. Key components of the intervention were mentoring at the sites by VTE prophylaxis experts, group webinars in best practices, and a “measure-vention.” Teams were taught how to rate patient risk for VTE and apply specific protocols according to risk rating using the SHM-mentored implementation model. Real-time monitoring of the intervention was used to make any necessary adjustments. When before-and-after data were compared, following the 18-month period during which the intervention was measured, Dr. Jenkins said an average of 330 VTEs were averted annually. “We found the results very gratifying,” said Dr. Jenkins.

“These projects all reflect a broader trend in hospital medicine where we are using the wealth of data we have now for quality improvement and for outcomes research,” Dr. Fang said in the interview.

There were no relevant disclosures.

This year’s RIV innovation winners reflect a nascent trend of applying informatics to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.

“One striking thing is that all three winners used either EHR or Big Data and large collaboratives to achieve their goals,” Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, and moderator of the winners’ panel, said in an interview. This year’s winners included a sleep-promoting “nudge” system that Dr. Fang said she expects will help improve sleep and lower rates of delirium and a source code that connects disparate data systems for daily updates on where quality can be improved. The third winner used what Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and the medical director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called a “classic quality improvement collaborative,” which simplifies the decision tree around venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis for better patient outcomes.

Calling uninterrupted sleep the “sine qua non” of patient care, RIV award recipient Vineet Arora, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, described the rationale for her RIV award-winning SIESTA (Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act) program. She and her colleagues surveyed hospitalists, nurses, residents, and patients to determine the most common sleep disrupters in their institution and devised “nudges” to alter how staff performed various tasks that otherwise might interfere with patient sleep. Rather than use overt incentives, nudges are changes in what Dr. Arora called the “choice architecture” of people’s behavior.

Based on survey feedback, Dr. Arora and her colleagues worked with their electronic health record (EHR) vendor to consolidate the performance of certain tasks that were affecting patient sleep. Reminders were added to daily nursing huddles to prompt them to look for ways they could decrease patient interruptions, and empowerment coaching was offered to nurses to encourage patient advocacy when physicians had given orders that would interfere with patients’ sleep.

When tested and measured over the course of a year, SIESTA’s EHR innovations resulted in six fewer nighttime disruptions than before the intervention, compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. The nursing-based interventions resulted in one less nocturnal interruption on average, also a significant change.

“If every patient were admitted into a SIESTA unit, 84% would say they were not disrupted by medications, compared to 57%. For interruptions for vitals, it would be 17% vs. 41%,” Dr. Arora said. In terms of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) data, this translates into as much as a 25th-percentile performance improvement for hospitals in related domains, according to Dr. Arora.

Nader Najafi, MD, an assistant clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, and his colleagues created Murmur, an open-source code data aggregator, which can be customized to solve a variety of quality improvement issues. RIV award winner Dr. Najafi applied the code to determine how systems failures in their institution were contributing to avoidable inpatient days, for example. At a daily appointed time, Murmur would determine which staff members were scheduled to work that day. Each provider would then receive a brief, customized survey about patients for that day on their cell phone. The data were then collected to create instant reports of where the delays in discharge were occurring.

Testing by gastroenterologists was pinpointed as a “huge source of delays, something we had never been able to quantify before, “ Dr. Najafi said. This led to brainstorming sessions with the department for solutions.

To reduce rates of hospital-associated VTE, 35 California hospitals with varying numbers of beds and locations collaborated on a project led by RIV award recipient Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. Key components of the intervention were mentoring at the sites by VTE prophylaxis experts, group webinars in best practices, and a “measure-vention.” Teams were taught how to rate patient risk for VTE and apply specific protocols according to risk rating using the SHM-mentored implementation model. Real-time monitoring of the intervention was used to make any necessary adjustments. When before-and-after data were compared, following the 18-month period during which the intervention was measured, Dr. Jenkins said an average of 330 VTEs were averted annually. “We found the results very gratifying,” said Dr. Jenkins.

“These projects all reflect a broader trend in hospital medicine where we are using the wealth of data we have now for quality improvement and for outcomes research,” Dr. Fang said in the interview.

There were no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Hospitalists can help improve antibiotic stewardship

Hospitalists can – and should – help curb unnecessary antibiotic use, according to an expert who spoke at HM17.

Nearly three-quarters of patients who have been diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia are receiving antibiotics for longer periods than necessary, either because the severity of their illness doesn’t warrant them or because they do not have pneumonia, according to Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, a research scientist in the division of hospital medicine and the Patient Safety Enhancement Program at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

“As hospitalists, we have a role to play in antibiotic stewardship,” Dr. Vaughn said in this interview recorded at the meeting.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hospitalists can – and should – help curb unnecessary antibiotic use, according to an expert who spoke at HM17.

Nearly three-quarters of patients who have been diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia are receiving antibiotics for longer periods than necessary, either because the severity of their illness doesn’t warrant them or because they do not have pneumonia, according to Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, a research scientist in the division of hospital medicine and the Patient Safety Enhancement Program at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

“As hospitalists, we have a role to play in antibiotic stewardship,” Dr. Vaughn said in this interview recorded at the meeting.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hospitalists can – and should – help curb unnecessary antibiotic use, according to an expert who spoke at HM17.

Nearly three-quarters of patients who have been diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia are receiving antibiotics for longer periods than necessary, either because the severity of their illness doesn’t warrant them or because they do not have pneumonia, according to Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, a research scientist in the division of hospital medicine and the Patient Safety Enhancement Program at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

“As hospitalists, we have a role to play in antibiotic stewardship,” Dr. Vaughn said in this interview recorded at the meeting.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO: How informatics can help your hospital prevent infections

Hospitalists have a powerful tool to help them fight outbreaks of Clostridium difficile and other infectious agents: electronic health record data.

Sara Murray, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues, used EHR data to map temporal and spatial coordinates to determine where patients in their hospital were at highest risk for C. difficile. Patients who’d had a CT scan on a particular machine in the emergency department within 24 hours of an infected person having been scanned there had a threefold higher risk of infection, they found. This information helped the hospital’s infection control team to create a more effective sterilization plan for that specific machine.

“The takeaway is that we should be leveraging our EHR data to inform our quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Murray said in this video interview, recorded during HM17.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hospitalists have a powerful tool to help them fight outbreaks of Clostridium difficile and other infectious agents: electronic health record data.

Sara Murray, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues, used EHR data to map temporal and spatial coordinates to determine where patients in their hospital were at highest risk for C. difficile. Patients who’d had a CT scan on a particular machine in the emergency department within 24 hours of an infected person having been scanned there had a threefold higher risk of infection, they found. This information helped the hospital’s infection control team to create a more effective sterilization plan for that specific machine.

“The takeaway is that we should be leveraging our EHR data to inform our quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Murray said in this video interview, recorded during HM17.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hospitalists have a powerful tool to help them fight outbreaks of Clostridium difficile and other infectious agents: electronic health record data.

Sara Murray, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues, used EHR data to map temporal and spatial coordinates to determine where patients in their hospital were at highest risk for C. difficile. Patients who’d had a CT scan on a particular machine in the emergency department within 24 hours of an infected person having been scanned there had a threefold higher risk of infection, they found. This information helped the hospital’s infection control team to create a more effective sterilization plan for that specific machine.

“The takeaway is that we should be leveraging our EHR data to inform our quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Murray said in this video interview, recorded during HM17.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Foresight and hard work – not inevitability – shaped HM, CEO says

So, the changing currents in medicine made it inevitable that the hospital medicine movement – and SHM – would have happened no matter what, right?

Not so much, said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“How did Netflix pop up and not Blockbuster? Why did Sears not become Amazon?” he asked. “I think that SHM is very proud that we – very early on, when there were just a couple hundred hospitalists – saw the potential for this specialty.” At the same time, he said, “many of the other medical associations that were hundreds of years old not only did not see the potential for our specialty but, in many ways, were [also] somewhat contrary to the kinds of things that all of you have been doing over the last 20 years.”

He acknowledged that there were some “winds at our back” – it was clear that many physicians were wanting to leave the hospital – but he said the hospital medicine movement and the society nonetheless had to push up against resistance to change.

The movement continues to grow, he noted. As proof, there are 57,000 hospitalists, according to American Hospital Association surveys, and 15,000 SHM members.

In a note of caution, he recognized the many roles hospitalists are being asked to fill – from patient-safety projects to perioperative work – and said “hospitalists are more likely to say ‘yes’ when they should probably say ‘maybe.’ ” At the same time, he praised hospitalists for their openness to new ways of thinking and their willingness to partner.

Despite uncertainty, he said the future of health care is right up SHM’s alley.

“The future fits what hospital medicine is all about: We’re about value, we’re about creating the new future,” he said. “We’re about being accountable for what we do, being measured, and improving off those measures. ... We understand that we need to give up some of our autonomy and be in an integrated process to benefit from the expertise and the energies of other people.”

He touted the vital role that hospitalists will play.

“As we stand here today, we are not just large. We are not just the fastest-growing medical specialty of all time,” he said. “We are the answer to many of the questions going forward.”

So, the changing currents in medicine made it inevitable that the hospital medicine movement – and SHM – would have happened no matter what, right?

Not so much, said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“How did Netflix pop up and not Blockbuster? Why did Sears not become Amazon?” he asked. “I think that SHM is very proud that we – very early on, when there were just a couple hundred hospitalists – saw the potential for this specialty.” At the same time, he said, “many of the other medical associations that were hundreds of years old not only did not see the potential for our specialty but, in many ways, were [also] somewhat contrary to the kinds of things that all of you have been doing over the last 20 years.”

He acknowledged that there were some “winds at our back” – it was clear that many physicians were wanting to leave the hospital – but he said the hospital medicine movement and the society nonetheless had to push up against resistance to change.

The movement continues to grow, he noted. As proof, there are 57,000 hospitalists, according to American Hospital Association surveys, and 15,000 SHM members.

In a note of caution, he recognized the many roles hospitalists are being asked to fill – from patient-safety projects to perioperative work – and said “hospitalists are more likely to say ‘yes’ when they should probably say ‘maybe.’ ” At the same time, he praised hospitalists for their openness to new ways of thinking and their willingness to partner.

Despite uncertainty, he said the future of health care is right up SHM’s alley.

“The future fits what hospital medicine is all about: We’re about value, we’re about creating the new future,” he said. “We’re about being accountable for what we do, being measured, and improving off those measures. ... We understand that we need to give up some of our autonomy and be in an integrated process to benefit from the expertise and the energies of other people.”

He touted the vital role that hospitalists will play.

“As we stand here today, we are not just large. We are not just the fastest-growing medical specialty of all time,” he said. “We are the answer to many of the questions going forward.”

So, the changing currents in medicine made it inevitable that the hospital medicine movement – and SHM – would have happened no matter what, right?

Not so much, said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“How did Netflix pop up and not Blockbuster? Why did Sears not become Amazon?” he asked. “I think that SHM is very proud that we – very early on, when there were just a couple hundred hospitalists – saw the potential for this specialty.” At the same time, he said, “many of the other medical associations that were hundreds of years old not only did not see the potential for our specialty but, in many ways, were [also] somewhat contrary to the kinds of things that all of you have been doing over the last 20 years.”

He acknowledged that there were some “winds at our back” – it was clear that many physicians were wanting to leave the hospital – but he said the hospital medicine movement and the society nonetheless had to push up against resistance to change.

The movement continues to grow, he noted. As proof, there are 57,000 hospitalists, according to American Hospital Association surveys, and 15,000 SHM members.

In a note of caution, he recognized the many roles hospitalists are being asked to fill – from patient-safety projects to perioperative work – and said “hospitalists are more likely to say ‘yes’ when they should probably say ‘maybe.’ ” At the same time, he praised hospitalists for their openness to new ways of thinking and their willingness to partner.

Despite uncertainty, he said the future of health care is right up SHM’s alley.

“The future fits what hospital medicine is all about: We’re about value, we’re about creating the new future,” he said. “We’re about being accountable for what we do, being measured, and improving off those measures. ... We understand that we need to give up some of our autonomy and be in an integrated process to benefit from the expertise and the energies of other people.”

He touted the vital role that hospitalists will play.

“As we stand here today, we are not just large. We are not just the fastest-growing medical specialty of all time,” he said. “We are the answer to many of the questions going forward.”

Conway says health care payment, quality reform to continue

Keynote speaker Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, told hospitalists at HM17 Wednesday that, while there is a seemingly endless stream of punditry about the fate of the Affordable Care Act, health care will continue its trajectory to higher value, lower costs, and improved quality for patients.

“Health system transformation, innovation, delivery system reform, accountability, the work that you all do each and every day ... is a bipartisan ideal,” he said. The work “on value, the work on accountability, the work on bundled payments ... will continue and will continue to be important to you and the patients you serve.”

He also echoed Tuesday’s keynote address from Karen DeSalvo, MD, former Acting Assistant Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, that hospital medicine needs to look at health care more holistically to help work on social issues. Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends, knows the problem first-hand as he often sees children on Medicaid who have multiple chronic conditions.

“I can tell you our system still does not have a highly reliable, whole health system for those children and their families,” he said. “Every weekend, I have a family that I can’t discharge because they don’t have the social and home-based supports for them to go home. So, they literally sit in the hospital until Monday. That makes no sense for our overall health system.”

Dr. Conway said that the gravitation away from fee-for-service toward alternative payment models would ideally lead to better patient outcomes, more coordinated care, and financial savings. He urged hospitalists to continue to help design new payment and care-delivery systems.

“You know what you’re passionate about and where you want to drive better care,” he said. “If the army of people in this room and all the places you are working [at] are the driver of better quality, better safety, coordinated care for patients ... that’s what it’s all about.”

Keynote speaker Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, told hospitalists at HM17 Wednesday that, while there is a seemingly endless stream of punditry about the fate of the Affordable Care Act, health care will continue its trajectory to higher value, lower costs, and improved quality for patients.

“Health system transformation, innovation, delivery system reform, accountability, the work that you all do each and every day ... is a bipartisan ideal,” he said. The work “on value, the work on accountability, the work on bundled payments ... will continue and will continue to be important to you and the patients you serve.”

He also echoed Tuesday’s keynote address from Karen DeSalvo, MD, former Acting Assistant Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, that hospital medicine needs to look at health care more holistically to help work on social issues. Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends, knows the problem first-hand as he often sees children on Medicaid who have multiple chronic conditions.

“I can tell you our system still does not have a highly reliable, whole health system for those children and their families,” he said. “Every weekend, I have a family that I can’t discharge because they don’t have the social and home-based supports for them to go home. So, they literally sit in the hospital until Monday. That makes no sense for our overall health system.”

Dr. Conway said that the gravitation away from fee-for-service toward alternative payment models would ideally lead to better patient outcomes, more coordinated care, and financial savings. He urged hospitalists to continue to help design new payment and care-delivery systems.

“You know what you’re passionate about and where you want to drive better care,” he said. “If the army of people in this room and all the places you are working [at] are the driver of better quality, better safety, coordinated care for patients ... that’s what it’s all about.”

Keynote speaker Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, told hospitalists at HM17 Wednesday that, while there is a seemingly endless stream of punditry about the fate of the Affordable Care Act, health care will continue its trajectory to higher value, lower costs, and improved quality for patients.

“Health system transformation, innovation, delivery system reform, accountability, the work that you all do each and every day ... is a bipartisan ideal,” he said. The work “on value, the work on accountability, the work on bundled payments ... will continue and will continue to be important to you and the patients you serve.”

He also echoed Tuesday’s keynote address from Karen DeSalvo, MD, former Acting Assistant Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, that hospital medicine needs to look at health care more holistically to help work on social issues. Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends, knows the problem first-hand as he often sees children on Medicaid who have multiple chronic conditions.

“I can tell you our system still does not have a highly reliable, whole health system for those children and their families,” he said. “Every weekend, I have a family that I can’t discharge because they don’t have the social and home-based supports for them to go home. So, they literally sit in the hospital until Monday. That makes no sense for our overall health system.”

Dr. Conway said that the gravitation away from fee-for-service toward alternative payment models would ideally lead to better patient outcomes, more coordinated care, and financial savings. He urged hospitalists to continue to help design new payment and care-delivery systems.

“You know what you’re passionate about and where you want to drive better care,” he said. “If the army of people in this room and all the places you are working [at] are the driver of better quality, better safety, coordinated care for patients ... that’s what it’s all about.”

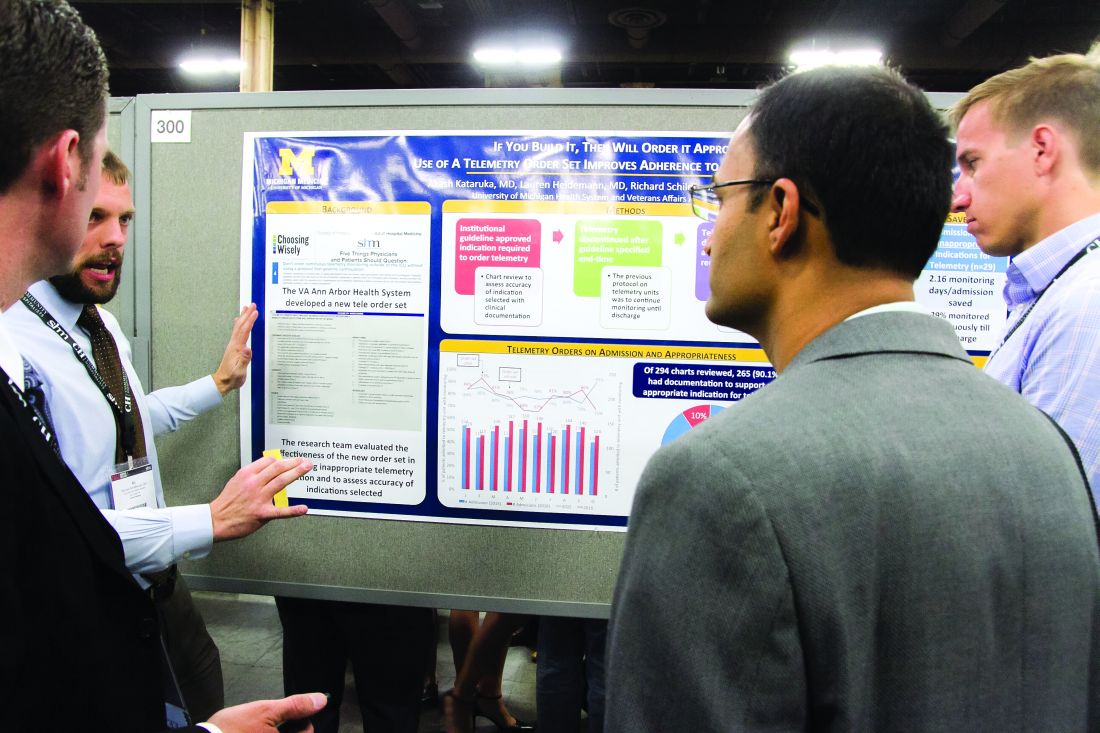

From idea to abstract, RIV posters highlight novel thinking

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

VIDEO: Attaining the tools to start your own quality improvement project

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Forum focuses on forging Q.I. connections

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Proper UTI diagnosis, treatment relies on cautious approach

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight