User login

Ways Hospitalists Can Support Advocacy for Patients, Hospital Medicine

There are so many ways to advocate for your patients, for your profession, for the future of hospital medicine. The easiest way? Getting involved.

We know how important it is to you that your patients receive the best care possible. We know that you do your absolute best as their provider but that sometimes there are hurdles that can hinder your capabilities until some kind of legislative change is enacted. SHM does its best to foresee these obstacles and works rigorously to achieve positive legislative outcomes, but often there are details we cannot fathom without your input and expertise. That’s why we need you, our hospitalist members, to fill in the gaps.

On April 1, the final day of Hospital Medicine 2015, SHM is hosting another “Hospitalists on the Hill” in Washington, D.C. We are so excited to join members on Capitol Hill again. Discussing healthcare issues that impact your patients and the specialty by meeting personally with legislators and their staff is an opportunity to share your experiences as a frontline hospitalist and directly impact key policy issues.

Want to learn more about how you can impact the process prior to heading to the Hill? Unable to attend Hill Day, but still want a better understanding of the legislative process and how SHM gets involved? Come to our “Policy Basics 101” session March 31 at HM15, where you’ll hear from SHM’s Government Relations team and from members of the Public Policy Committee. You will not only learn about the legislative and regulatory processes, but you can also discover where hospitalists can take part and exert influence along the way.

If you find that you’re unable to attend the face-to-face meetings on April 1, or even if you are, make sure that you are a member of SHM’s Grassroots Network. SHM uses this venue to keep you informed of the healthcare policy decisions on the horizon and asks you to take only a few minutes to reach out to your representatives via e-mail to take action on the issues most important to hospital medicine.

The Grassroots Network has grown substantially over the past few years, but we are always looking for more hospitalists to take up the cause. Strength in numbers is the most effective way to tell Congress where change is needed. Sign up directly.

Whether you do it in person on Capitol Hill or through periodic e-mails to legislators, advocating for patients and the specialty of hospital medicine is important work, and we hope you’ll continue to help us in even greater numbers in the future. Hospitalists have a unique voice in the healthcare system—one that needs to be shared and engaged in critical policy discussions. We hope you’ll join us in the movement to advocate for hospitalists, for your patients, and for hospital medicine.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

There are so many ways to advocate for your patients, for your profession, for the future of hospital medicine. The easiest way? Getting involved.

We know how important it is to you that your patients receive the best care possible. We know that you do your absolute best as their provider but that sometimes there are hurdles that can hinder your capabilities until some kind of legislative change is enacted. SHM does its best to foresee these obstacles and works rigorously to achieve positive legislative outcomes, but often there are details we cannot fathom without your input and expertise. That’s why we need you, our hospitalist members, to fill in the gaps.

On April 1, the final day of Hospital Medicine 2015, SHM is hosting another “Hospitalists on the Hill” in Washington, D.C. We are so excited to join members on Capitol Hill again. Discussing healthcare issues that impact your patients and the specialty by meeting personally with legislators and their staff is an opportunity to share your experiences as a frontline hospitalist and directly impact key policy issues.

Want to learn more about how you can impact the process prior to heading to the Hill? Unable to attend Hill Day, but still want a better understanding of the legislative process and how SHM gets involved? Come to our “Policy Basics 101” session March 31 at HM15, where you’ll hear from SHM’s Government Relations team and from members of the Public Policy Committee. You will not only learn about the legislative and regulatory processes, but you can also discover where hospitalists can take part and exert influence along the way.

If you find that you’re unable to attend the face-to-face meetings on April 1, or even if you are, make sure that you are a member of SHM’s Grassroots Network. SHM uses this venue to keep you informed of the healthcare policy decisions on the horizon and asks you to take only a few minutes to reach out to your representatives via e-mail to take action on the issues most important to hospital medicine.

The Grassroots Network has grown substantially over the past few years, but we are always looking for more hospitalists to take up the cause. Strength in numbers is the most effective way to tell Congress where change is needed. Sign up directly.

Whether you do it in person on Capitol Hill or through periodic e-mails to legislators, advocating for patients and the specialty of hospital medicine is important work, and we hope you’ll continue to help us in even greater numbers in the future. Hospitalists have a unique voice in the healthcare system—one that needs to be shared and engaged in critical policy discussions. We hope you’ll join us in the movement to advocate for hospitalists, for your patients, and for hospital medicine.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

There are so many ways to advocate for your patients, for your profession, for the future of hospital medicine. The easiest way? Getting involved.

We know how important it is to you that your patients receive the best care possible. We know that you do your absolute best as their provider but that sometimes there are hurdles that can hinder your capabilities until some kind of legislative change is enacted. SHM does its best to foresee these obstacles and works rigorously to achieve positive legislative outcomes, but often there are details we cannot fathom without your input and expertise. That’s why we need you, our hospitalist members, to fill in the gaps.

On April 1, the final day of Hospital Medicine 2015, SHM is hosting another “Hospitalists on the Hill” in Washington, D.C. We are so excited to join members on Capitol Hill again. Discussing healthcare issues that impact your patients and the specialty by meeting personally with legislators and their staff is an opportunity to share your experiences as a frontline hospitalist and directly impact key policy issues.

Want to learn more about how you can impact the process prior to heading to the Hill? Unable to attend Hill Day, but still want a better understanding of the legislative process and how SHM gets involved? Come to our “Policy Basics 101” session March 31 at HM15, where you’ll hear from SHM’s Government Relations team and from members of the Public Policy Committee. You will not only learn about the legislative and regulatory processes, but you can also discover where hospitalists can take part and exert influence along the way.

If you find that you’re unable to attend the face-to-face meetings on April 1, or even if you are, make sure that you are a member of SHM’s Grassroots Network. SHM uses this venue to keep you informed of the healthcare policy decisions on the horizon and asks you to take only a few minutes to reach out to your representatives via e-mail to take action on the issues most important to hospital medicine.

The Grassroots Network has grown substantially over the past few years, but we are always looking for more hospitalists to take up the cause. Strength in numbers is the most effective way to tell Congress where change is needed. Sign up directly.

Whether you do it in person on Capitol Hill or through periodic e-mails to legislators, advocating for patients and the specialty of hospital medicine is important work, and we hope you’ll continue to help us in even greater numbers in the future. Hospitalists have a unique voice in the healthcare system—one that needs to be shared and engaged in critical policy discussions. We hope you’ll join us in the movement to advocate for hospitalists, for your patients, and for hospital medicine.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

HM15 At Hand Conference App Helps Hospitalists Plan Schedule

With the largest national conference for hospitalists just weeks away, now is the time to use the HM15 conference app to plan your schedule. HM15 At Hand—available now—can help you create a simple agenda by distilling down the dozens of sessions, exhibitors, and events.

HM15 At Hand is the ultimate companion for HM15 attendees, providing:

- Personalized agenda. Look up sessions of interest by day, track, speaker, or even how they apply to maintenance of certification.

- Presentation materials. Slide decks and other materials will be available exclusively on HM15 At Hand.

- Other attendees. HM15 makes finding and connecting with other attendees easy.

- Exhibitor information. Hundreds of exhibitors will be at HM15. HM15 At Hand makes your smartphone or tablet your guide to making the right connections with the leaders in the hospital medicine marketplace.

- Maps. HM15 At Hand can help you find your way through the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center with digital maps.

With the largest national conference for hospitalists just weeks away, now is the time to use the HM15 conference app to plan your schedule. HM15 At Hand—available now—can help you create a simple agenda by distilling down the dozens of sessions, exhibitors, and events.

HM15 At Hand is the ultimate companion for HM15 attendees, providing:

- Personalized agenda. Look up sessions of interest by day, track, speaker, or even how they apply to maintenance of certification.

- Presentation materials. Slide decks and other materials will be available exclusively on HM15 At Hand.

- Other attendees. HM15 makes finding and connecting with other attendees easy.

- Exhibitor information. Hundreds of exhibitors will be at HM15. HM15 At Hand makes your smartphone or tablet your guide to making the right connections with the leaders in the hospital medicine marketplace.

- Maps. HM15 At Hand can help you find your way through the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center with digital maps.

With the largest national conference for hospitalists just weeks away, now is the time to use the HM15 conference app to plan your schedule. HM15 At Hand—available now—can help you create a simple agenda by distilling down the dozens of sessions, exhibitors, and events.

HM15 At Hand is the ultimate companion for HM15 attendees, providing:

- Personalized agenda. Look up sessions of interest by day, track, speaker, or even how they apply to maintenance of certification.

- Presentation materials. Slide decks and other materials will be available exclusively on HM15 At Hand.

- Other attendees. HM15 makes finding and connecting with other attendees easy.

- Exhibitor information. Hundreds of exhibitors will be at HM15. HM15 At Hand makes your smartphone or tablet your guide to making the right connections with the leaders in the hospital medicine marketplace.

- Maps. HM15 At Hand can help you find your way through the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center with digital maps.

Educational Opportunities for Hospitalists Beyond HM15

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Society of Hospital Medicine's Quality Improvement Module Approved for ABIM Maintenance of Certification

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

How Academic Hospitalists Can Balance Teaching, Nonteaching Roles

As a group director at a growing, university-based hospitalist program, I often interview aspiring academic hospitalists. Inevitably, the conversation turns to a coveted aspect of the job. I’m not talking about the salary. Applicants want to know, “How much time will I spend on teaching services?”

Because hospitalists at academic institutions typically are passionate about their work as instructors and mentors, they highly value time with trainees. Unfortunately, the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work hour rules triggered an expansion in non-teaching services at many teaching hospitals, forcing groups either to divide teaching service among an increasing number of attending physicians or to allocate this commodity unevenly on grounds such as seniority. For many group leaders, striking the right balance between teaching and non-teaching service can be an important contributor to recruitment and retention. During these interviews, I’ve often wondered how our group compares to others around the country.

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM) shines light on this topic.

Among the 422 groups that only care for adults, 52 self-reported as academic groups. The groups were then asked to describe how they distribute work duties. In these academic practices, about half (52.5%) of the group’s full-time equivalents (FTEs) were devoted to clinical work in which the attending supervises learners delivering care. The remaining FTEs were devoted to a mix of clinical work on non-teaching services, administration, and protected time for research.

Interestingly, the portion devoted to clinical teaching differs substantially between university-based and affiliated community teaching hospitals (36.2% vs. 79.1%), suggesting that hospitalists face tough competition for teaching time at the main campuses of academic systems but might have more opportunities to teach at the bedside in faculty jobs at affiliated hospitals.

The above FTE figures represent averages, which don’t tell the whole story. Groups might not distribute teaching time evenly; the approach to allocation ranges from a completely egalitarian approach to a system with two tiers that separate teaching and non-teaching hospitalists.

To address the ranges, the State of Hospital Medicine survey asked respondents to divide their faculty into five categories of individual job types, ranging from “No clinical activity with trainees” to “>75% of clinical activity with trainees” (see Figure 1). The results show a broad array of teaching responsibilities, with 20% of academic hospitalists spending no time teaching and another 21% spending almost all of their time teaching.

I suspect this distribution partially reflects the underlying interests of the individual hospitalists, but it is also a product of the available opportunities. A few factors might influence those opportunities, such as decisions by the hospital to hire hospitalists rather than nurse practitioners and physicians assistants to cover new services, or the presence of specialists and general internists who share teaching service slots with hospitalists.

One of the great things about SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report is how it depicts the wide variety of careers available to hospitalists; the teaching environment is no exception. Although I strive to help my colleagues tailor positions to suit their interests, we never have quite enough resident service time to meet the demands of our enthusiastic teachers. Fortunately, this report allows me to discuss our job openings with candidates knowing how we stack up against academic programs around the country.

Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Washington and hospitalist group director at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle.

As a group director at a growing, university-based hospitalist program, I often interview aspiring academic hospitalists. Inevitably, the conversation turns to a coveted aspect of the job. I’m not talking about the salary. Applicants want to know, “How much time will I spend on teaching services?”

Because hospitalists at academic institutions typically are passionate about their work as instructors and mentors, they highly value time with trainees. Unfortunately, the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work hour rules triggered an expansion in non-teaching services at many teaching hospitals, forcing groups either to divide teaching service among an increasing number of attending physicians or to allocate this commodity unevenly on grounds such as seniority. For many group leaders, striking the right balance between teaching and non-teaching service can be an important contributor to recruitment and retention. During these interviews, I’ve often wondered how our group compares to others around the country.

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM) shines light on this topic.

Among the 422 groups that only care for adults, 52 self-reported as academic groups. The groups were then asked to describe how they distribute work duties. In these academic practices, about half (52.5%) of the group’s full-time equivalents (FTEs) were devoted to clinical work in which the attending supervises learners delivering care. The remaining FTEs were devoted to a mix of clinical work on non-teaching services, administration, and protected time for research.

Interestingly, the portion devoted to clinical teaching differs substantially between university-based and affiliated community teaching hospitals (36.2% vs. 79.1%), suggesting that hospitalists face tough competition for teaching time at the main campuses of academic systems but might have more opportunities to teach at the bedside in faculty jobs at affiliated hospitals.

The above FTE figures represent averages, which don’t tell the whole story. Groups might not distribute teaching time evenly; the approach to allocation ranges from a completely egalitarian approach to a system with two tiers that separate teaching and non-teaching hospitalists.

To address the ranges, the State of Hospital Medicine survey asked respondents to divide their faculty into five categories of individual job types, ranging from “No clinical activity with trainees” to “>75% of clinical activity with trainees” (see Figure 1). The results show a broad array of teaching responsibilities, with 20% of academic hospitalists spending no time teaching and another 21% spending almost all of their time teaching.

I suspect this distribution partially reflects the underlying interests of the individual hospitalists, but it is also a product of the available opportunities. A few factors might influence those opportunities, such as decisions by the hospital to hire hospitalists rather than nurse practitioners and physicians assistants to cover new services, or the presence of specialists and general internists who share teaching service slots with hospitalists.

One of the great things about SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report is how it depicts the wide variety of careers available to hospitalists; the teaching environment is no exception. Although I strive to help my colleagues tailor positions to suit their interests, we never have quite enough resident service time to meet the demands of our enthusiastic teachers. Fortunately, this report allows me to discuss our job openings with candidates knowing how we stack up against academic programs around the country.

Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Washington and hospitalist group director at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle.

As a group director at a growing, university-based hospitalist program, I often interview aspiring academic hospitalists. Inevitably, the conversation turns to a coveted aspect of the job. I’m not talking about the salary. Applicants want to know, “How much time will I spend on teaching services?”

Because hospitalists at academic institutions typically are passionate about their work as instructors and mentors, they highly value time with trainees. Unfortunately, the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work hour rules triggered an expansion in non-teaching services at many teaching hospitals, forcing groups either to divide teaching service among an increasing number of attending physicians or to allocate this commodity unevenly on grounds such as seniority. For many group leaders, striking the right balance between teaching and non-teaching service can be an important contributor to recruitment and retention. During these interviews, I’ve often wondered how our group compares to others around the country.

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM) shines light on this topic.

Among the 422 groups that only care for adults, 52 self-reported as academic groups. The groups were then asked to describe how they distribute work duties. In these academic practices, about half (52.5%) of the group’s full-time equivalents (FTEs) were devoted to clinical work in which the attending supervises learners delivering care. The remaining FTEs were devoted to a mix of clinical work on non-teaching services, administration, and protected time for research.

Interestingly, the portion devoted to clinical teaching differs substantially between university-based and affiliated community teaching hospitals (36.2% vs. 79.1%), suggesting that hospitalists face tough competition for teaching time at the main campuses of academic systems but might have more opportunities to teach at the bedside in faculty jobs at affiliated hospitals.

The above FTE figures represent averages, which don’t tell the whole story. Groups might not distribute teaching time evenly; the approach to allocation ranges from a completely egalitarian approach to a system with two tiers that separate teaching and non-teaching hospitalists.

To address the ranges, the State of Hospital Medicine survey asked respondents to divide their faculty into five categories of individual job types, ranging from “No clinical activity with trainees” to “>75% of clinical activity with trainees” (see Figure 1). The results show a broad array of teaching responsibilities, with 20% of academic hospitalists spending no time teaching and another 21% spending almost all of their time teaching.

I suspect this distribution partially reflects the underlying interests of the individual hospitalists, but it is also a product of the available opportunities. A few factors might influence those opportunities, such as decisions by the hospital to hire hospitalists rather than nurse practitioners and physicians assistants to cover new services, or the presence of specialists and general internists who share teaching service slots with hospitalists.

One of the great things about SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report is how it depicts the wide variety of careers available to hospitalists; the teaching environment is no exception. Although I strive to help my colleagues tailor positions to suit their interests, we never have quite enough resident service time to meet the demands of our enthusiastic teachers. Fortunately, this report allows me to discuss our job openings with candidates knowing how we stack up against academic programs around the country.

Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Washington and hospitalist group director at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle.

Society of Hospital Medicine’s Quality Improvement Toolkits Bring Best Practices to Hospitals

SHM’s free quality improvement toolkits bring the very best practices in the most pressing hospital issues right to your hospital.

With topics like discharging to post-acute care facilities, pain management, and diabetes, SHM helps thousands of hospitals tackle these issues—all with the confidence and expertise of the leaders in the field.

For the latest toolkits, including those designed for post-acute care and glycemic control, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

SHM’s free quality improvement toolkits bring the very best practices in the most pressing hospital issues right to your hospital.

With topics like discharging to post-acute care facilities, pain management, and diabetes, SHM helps thousands of hospitals tackle these issues—all with the confidence and expertise of the leaders in the field.

For the latest toolkits, including those designed for post-acute care and glycemic control, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

SHM’s free quality improvement toolkits bring the very best practices in the most pressing hospital issues right to your hospital.

With topics like discharging to post-acute care facilities, pain management, and diabetes, SHM helps thousands of hospitals tackle these issues—all with the confidence and expertise of the leaders in the field.

For the latest toolkits, including those designed for post-acute care and glycemic control, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

Greater Transparency for Financial Information in Healthcare Will Prompt Questions from Patients

The movement toward greater transparency of financial information in healthcare is providing patients with access to data that might affect their healthcare decisions. Not all of this information is provided in ways that give patients the full picture, and they may turn to you for some added clarity.

Financial Relationships

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (“Sunshine Act’) was passed as a part of the Affordable Care Act and requires the public disclosure of financial relationships between physicians and the manufacturers of pharmaceuticals, devices, and supplies, as well as group purchasing organizations. The first wave of financial information was publicly disclosed in 2014 on the federal Open Payments website. When it went live, the website disclosed approximately $3.5 billion in payments made by manufacturers to physicians and teaching hospitals during the last five months of 2013. These payments include research grants, consulting fees, speaking fees, travel, and other expenses. In the future, the payments reported will span an entire year, further increasing the total dollar amount paid by industry.

The Sunshine Act is intended to expose potential conflicts of interest in healthcare so that patients are more informed consumers of healthcare services. The relationships between healthcare providers and industry have been scrutinized much more heavily over the past decade. The concern is that physicians with a financial interest, whether through a consultancy relationship with industry or through the development of new technology, might be biased in treating patients because of these relationships. On the other hand, the majority of relationships between healthcare providers and industry can be beneficial. The relationships provide education to other providers, encourage the development of new treatment options, and improve the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) explains on its website that the disclosed financial ties are not necessarily indicators of any wrongdoing, and that the intent of publishing the information is to promote transparency and discourage inappropriate relationships. Without the proper context, these relationships could be viewed as improper by patients and the general public. Therefore, providers should be prepared to answer patients’ questions and possibly even proactively provide details, such as the scope of any relationship with industry. Many providers begin to consult with a pharmaceutical or device manufacturer because of their experience using a particular product, rather than using a particular product after forming that financial relationship. This context could shift patients’ views of what it means for their providers to have this type of connection with industry.

Providers also need to be aware that government agencies, insurers, and attorneys can track this data. Although it is still too early to know the full scope of the potential uses of this information in government investigations, insurance carrier decisions, malpractice, or other legal actions, it does provide further reason to ensure that the information posted is accurate.

During the initial launch of the Open Payments website, some data was temporarily removed due to inaccuracies, including payments linked incorrectly to physicians with the same first and last names. While these issues are being reviewed by CMS, their existence proves how important it is for all physicians (even those not affiliated with the industry) to review the data reported in order to ensure the accuracy of their information.

Procedure Costs

Another transparency requirement in the Affordable Care Act was implemented on Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the inpatient prospective payment system final rule. Hospitals are now required to make their prices for procedures public and update the list annually. The final rule is not explicit with respect to the manner of the disclosure, except that either a price list or the policy for obtaining access must be made public. Some complain that the rule is difficult to comply with because it is vague, while others point out that this fact gives hospitals necessary flexibility in the method of reporting. It is at the hospital’s discretion whether to post the information online or in a physical location.

It is important to note that patients with private payer insurance coverage have distinct rates that are set through agreements between their health plans and the hospitals, so information on the public list very likely will not be applicable to those patients and could be a source of confusion.

As patients have more access to information about the costs for procedures, providers need to be aware of where within the facility they should refer patients with questions or concerns, including information on a hospital’s financial assistance programs.

There are so many sources of information that patients and their families can obtain before ever setting foot in the hospital. An open dialogue with patients that emphasizes the context of any financial relationships with industry, including the benefits, can help to minimize the potential that the information will be treated as suspect by your patients.

Further, as patients bear more of the costs of healthcare, questions surrounding the costs of procedures relative to published data may be encountered more frequently at the bedside and in office visits. This information may have an impact on patients’ decisions about their care.

The movement toward greater transparency of financial information in healthcare is providing patients with access to data that might affect their healthcare decisions. Not all of this information is provided in ways that give patients the full picture, and they may turn to you for some added clarity.

Financial Relationships

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (“Sunshine Act’) was passed as a part of the Affordable Care Act and requires the public disclosure of financial relationships between physicians and the manufacturers of pharmaceuticals, devices, and supplies, as well as group purchasing organizations. The first wave of financial information was publicly disclosed in 2014 on the federal Open Payments website. When it went live, the website disclosed approximately $3.5 billion in payments made by manufacturers to physicians and teaching hospitals during the last five months of 2013. These payments include research grants, consulting fees, speaking fees, travel, and other expenses. In the future, the payments reported will span an entire year, further increasing the total dollar amount paid by industry.

The Sunshine Act is intended to expose potential conflicts of interest in healthcare so that patients are more informed consumers of healthcare services. The relationships between healthcare providers and industry have been scrutinized much more heavily over the past decade. The concern is that physicians with a financial interest, whether through a consultancy relationship with industry or through the development of new technology, might be biased in treating patients because of these relationships. On the other hand, the majority of relationships between healthcare providers and industry can be beneficial. The relationships provide education to other providers, encourage the development of new treatment options, and improve the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) explains on its website that the disclosed financial ties are not necessarily indicators of any wrongdoing, and that the intent of publishing the information is to promote transparency and discourage inappropriate relationships. Without the proper context, these relationships could be viewed as improper by patients and the general public. Therefore, providers should be prepared to answer patients’ questions and possibly even proactively provide details, such as the scope of any relationship with industry. Many providers begin to consult with a pharmaceutical or device manufacturer because of their experience using a particular product, rather than using a particular product after forming that financial relationship. This context could shift patients’ views of what it means for their providers to have this type of connection with industry.

Providers also need to be aware that government agencies, insurers, and attorneys can track this data. Although it is still too early to know the full scope of the potential uses of this information in government investigations, insurance carrier decisions, malpractice, or other legal actions, it does provide further reason to ensure that the information posted is accurate.

During the initial launch of the Open Payments website, some data was temporarily removed due to inaccuracies, including payments linked incorrectly to physicians with the same first and last names. While these issues are being reviewed by CMS, their existence proves how important it is for all physicians (even those not affiliated with the industry) to review the data reported in order to ensure the accuracy of their information.

Procedure Costs

Another transparency requirement in the Affordable Care Act was implemented on Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the inpatient prospective payment system final rule. Hospitals are now required to make their prices for procedures public and update the list annually. The final rule is not explicit with respect to the manner of the disclosure, except that either a price list or the policy for obtaining access must be made public. Some complain that the rule is difficult to comply with because it is vague, while others point out that this fact gives hospitals necessary flexibility in the method of reporting. It is at the hospital’s discretion whether to post the information online or in a physical location.

It is important to note that patients with private payer insurance coverage have distinct rates that are set through agreements between their health plans and the hospitals, so information on the public list very likely will not be applicable to those patients and could be a source of confusion.

As patients have more access to information about the costs for procedures, providers need to be aware of where within the facility they should refer patients with questions or concerns, including information on a hospital’s financial assistance programs.

There are so many sources of information that patients and their families can obtain before ever setting foot in the hospital. An open dialogue with patients that emphasizes the context of any financial relationships with industry, including the benefits, can help to minimize the potential that the information will be treated as suspect by your patients.

Further, as patients bear more of the costs of healthcare, questions surrounding the costs of procedures relative to published data may be encountered more frequently at the bedside and in office visits. This information may have an impact on patients’ decisions about their care.

The movement toward greater transparency of financial information in healthcare is providing patients with access to data that might affect their healthcare decisions. Not all of this information is provided in ways that give patients the full picture, and they may turn to you for some added clarity.

Financial Relationships

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (“Sunshine Act’) was passed as a part of the Affordable Care Act and requires the public disclosure of financial relationships between physicians and the manufacturers of pharmaceuticals, devices, and supplies, as well as group purchasing organizations. The first wave of financial information was publicly disclosed in 2014 on the federal Open Payments website. When it went live, the website disclosed approximately $3.5 billion in payments made by manufacturers to physicians and teaching hospitals during the last five months of 2013. These payments include research grants, consulting fees, speaking fees, travel, and other expenses. In the future, the payments reported will span an entire year, further increasing the total dollar amount paid by industry.

The Sunshine Act is intended to expose potential conflicts of interest in healthcare so that patients are more informed consumers of healthcare services. The relationships between healthcare providers and industry have been scrutinized much more heavily over the past decade. The concern is that physicians with a financial interest, whether through a consultancy relationship with industry or through the development of new technology, might be biased in treating patients because of these relationships. On the other hand, the majority of relationships between healthcare providers and industry can be beneficial. The relationships provide education to other providers, encourage the development of new treatment options, and improve the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) explains on its website that the disclosed financial ties are not necessarily indicators of any wrongdoing, and that the intent of publishing the information is to promote transparency and discourage inappropriate relationships. Without the proper context, these relationships could be viewed as improper by patients and the general public. Therefore, providers should be prepared to answer patients’ questions and possibly even proactively provide details, such as the scope of any relationship with industry. Many providers begin to consult with a pharmaceutical or device manufacturer because of their experience using a particular product, rather than using a particular product after forming that financial relationship. This context could shift patients’ views of what it means for their providers to have this type of connection with industry.

Providers also need to be aware that government agencies, insurers, and attorneys can track this data. Although it is still too early to know the full scope of the potential uses of this information in government investigations, insurance carrier decisions, malpractice, or other legal actions, it does provide further reason to ensure that the information posted is accurate.

During the initial launch of the Open Payments website, some data was temporarily removed due to inaccuracies, including payments linked incorrectly to physicians with the same first and last names. While these issues are being reviewed by CMS, their existence proves how important it is for all physicians (even those not affiliated with the industry) to review the data reported in order to ensure the accuracy of their information.

Procedure Costs

Another transparency requirement in the Affordable Care Act was implemented on Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the inpatient prospective payment system final rule. Hospitals are now required to make their prices for procedures public and update the list annually. The final rule is not explicit with respect to the manner of the disclosure, except that either a price list or the policy for obtaining access must be made public. Some complain that the rule is difficult to comply with because it is vague, while others point out that this fact gives hospitals necessary flexibility in the method of reporting. It is at the hospital’s discretion whether to post the information online or in a physical location.

It is important to note that patients with private payer insurance coverage have distinct rates that are set through agreements between their health plans and the hospitals, so information on the public list very likely will not be applicable to those patients and could be a source of confusion.

As patients have more access to information about the costs for procedures, providers need to be aware of where within the facility they should refer patients with questions or concerns, including information on a hospital’s financial assistance programs.

There are so many sources of information that patients and their families can obtain before ever setting foot in the hospital. An open dialogue with patients that emphasizes the context of any financial relationships with industry, including the benefits, can help to minimize the potential that the information will be treated as suspect by your patients.

Further, as patients bear more of the costs of healthcare, questions surrounding the costs of procedures relative to published data may be encountered more frequently at the bedside and in office visits. This information may have an impact on patients’ decisions about their care.

Clinical Images Capture Hospitalists’ Daily Rounds

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

Hospitalists' Holistic Approach Draws Monal Shah, MD to Hospital Medicine

There was just something about hospitalized patients and the folks who cared for them that drew the attention of Monal Shah, MD. Midway through residency, he decided that the best word for it was respect. For the doctors and the people they treated—respect.

“I also liked that [the hospitalists] had a depth of knowledge outside of clinical care that was still important in managing patients: e.g. what insurance pays for what service, how to facilitate outpatient follow-up appointments, the importance of social factors in preventing a patient from returning to the hospital, etc.,” Dr. Shah says. “Even though we weren’t in an outpatient setting, I really appreciated that holistic approach and knowledge base required to care for inpatients.”

That was more than a decade ago at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. In the intervening years, Dr. Shah has become involved in clinical informatics and works with a nonprofit company developing prediction models and surveillance analytics for healthcare systems. He also serves as a physician advisor for Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas.

Question: I have your CV, but tell me a little more about your training in medical school and residency. What did you like most [and] dislike during the process? Was there a single moment you knew “I can do this”?

Answer: I really enjoyed the camaraderie of residency, especially when I was on an inpatient service and worked with a team [residents, interns, students, and attending]. I was fortunate to have an amazing group of people who inspired me to become a better clinician. I liked clinic the least. I still have days when I’m not sure if “I can do this.”

Q: What’s the biggest change you would like to see in hospital medicine?

A: With information overload, I feel like it’s pretty easy to figure out how to clinically care for a patient. For example, knowing which antibiotic to give for a certain infection is pretty easy to figure out. But knowing which IV antibiotics can/should be given in a nursing facility or at home is more nuanced and forces providers to address and think about the financial and social implications of healthcare. I think that it’s helpful for all specialties to have understanding about this, so the earlier that this type of training occurs (i.e., medical school), the better.

Q: Clinical informatics is clearly a growing area of interest for many. What about it appeals to you? How would you like to apply that knowledge to HM?

A: I found the EHR [electronic health record] to be very valuable, and it’s become difficult to imagine what it was like practicing in the pre-electronic era, but, with it, there definitely is information overload. Specifically, there is lots of duplicative/repetitive information coupled with new information (e.g. labs, vitals, imaging, notes) continuously being generated. Unless you’re sitting at the EMR [electronic medical record] or being notified every time something new appears, it’s almost impossible to know what is going on with the patient in real time. Clinical informatics has the ability to look for the most salient pieces of information—for instance, specific labs or radiology findings or specific words a clinician/nurse might use through natural language processing, etc. [We can] synthesize that information in real time to identify patients with certain diseases—like sepsis, where treatment with antibiotics is time-sensitive, or those who are at risk for adverse events. [We can identify,] for example, those patients at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest, readmission, etc.

Q: You’ve talked about access to data. How do you access the technology? How often? What about it works best for you? Is it something you wish older docs used more?

A: There is so much information ... that is constantly being generated [that] it makes it almost impossible to stay up to date on everything. Rather than even attempt to memorize every single treatment, I make an effort to know where to look for standard of care treatment regimens (e.g. ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] anticoagulation guidelines, IDSA [Infectious Diseases Society of America] guidelines, ACC/AHA [American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association] peri-operative guidelines). I use technology daily, probably looking up something on at least half of the patients I’m taking care of [on] a given day.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Being able to say no.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Students and residents that I’ve worked with who choose a career in HM.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Seeing a patient get well enough to be discharged home or to a lower level of care.

Q: What’s the best advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to anyone asking for help in managing a patient.

Q: What’s the worst advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to every job opportunity.

Q: Did you have a mentor during training or early career? If so, who was the mentor and what were the most important lessons you learned from him/her?

A: My division chief, although he probably didn’t know it. He was firm and had a clear direction for the division/program; however, he was very affable and had a delicate touch when dealing with the other physicians.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

There was just something about hospitalized patients and the folks who cared for them that drew the attention of Monal Shah, MD. Midway through residency, he decided that the best word for it was respect. For the doctors and the people they treated—respect.

“I also liked that [the hospitalists] had a depth of knowledge outside of clinical care that was still important in managing patients: e.g. what insurance pays for what service, how to facilitate outpatient follow-up appointments, the importance of social factors in preventing a patient from returning to the hospital, etc.,” Dr. Shah says. “Even though we weren’t in an outpatient setting, I really appreciated that holistic approach and knowledge base required to care for inpatients.”

That was more than a decade ago at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. In the intervening years, Dr. Shah has become involved in clinical informatics and works with a nonprofit company developing prediction models and surveillance analytics for healthcare systems. He also serves as a physician advisor for Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas.

Question: I have your CV, but tell me a little more about your training in medical school and residency. What did you like most [and] dislike during the process? Was there a single moment you knew “I can do this”?

Answer: I really enjoyed the camaraderie of residency, especially when I was on an inpatient service and worked with a team [residents, interns, students, and attending]. I was fortunate to have an amazing group of people who inspired me to become a better clinician. I liked clinic the least. I still have days when I’m not sure if “I can do this.”

Q: What’s the biggest change you would like to see in hospital medicine?

A: With information overload, I feel like it’s pretty easy to figure out how to clinically care for a patient. For example, knowing which antibiotic to give for a certain infection is pretty easy to figure out. But knowing which IV antibiotics can/should be given in a nursing facility or at home is more nuanced and forces providers to address and think about the financial and social implications of healthcare. I think that it’s helpful for all specialties to have understanding about this, so the earlier that this type of training occurs (i.e., medical school), the better.

Q: Clinical informatics is clearly a growing area of interest for many. What about it appeals to you? How would you like to apply that knowledge to HM?

A: I found the EHR [electronic health record] to be very valuable, and it’s become difficult to imagine what it was like practicing in the pre-electronic era, but, with it, there definitely is information overload. Specifically, there is lots of duplicative/repetitive information coupled with new information (e.g. labs, vitals, imaging, notes) continuously being generated. Unless you’re sitting at the EMR [electronic medical record] or being notified every time something new appears, it’s almost impossible to know what is going on with the patient in real time. Clinical informatics has the ability to look for the most salient pieces of information—for instance, specific labs or radiology findings or specific words a clinician/nurse might use through natural language processing, etc. [We can] synthesize that information in real time to identify patients with certain diseases—like sepsis, where treatment with antibiotics is time-sensitive, or those who are at risk for adverse events. [We can identify,] for example, those patients at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest, readmission, etc.

Q: You’ve talked about access to data. How do you access the technology? How often? What about it works best for you? Is it something you wish older docs used more?

A: There is so much information ... that is constantly being generated [that] it makes it almost impossible to stay up to date on everything. Rather than even attempt to memorize every single treatment, I make an effort to know where to look for standard of care treatment regimens (e.g. ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] anticoagulation guidelines, IDSA [Infectious Diseases Society of America] guidelines, ACC/AHA [American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association] peri-operative guidelines). I use technology daily, probably looking up something on at least half of the patients I’m taking care of [on] a given day.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Being able to say no.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Students and residents that I’ve worked with who choose a career in HM.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Seeing a patient get well enough to be discharged home or to a lower level of care.

Q: What’s the best advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to anyone asking for help in managing a patient.

Q: What’s the worst advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to every job opportunity.

Q: Did you have a mentor during training or early career? If so, who was the mentor and what were the most important lessons you learned from him/her?

A: My division chief, although he probably didn’t know it. He was firm and had a clear direction for the division/program; however, he was very affable and had a delicate touch when dealing with the other physicians.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

There was just something about hospitalized patients and the folks who cared for them that drew the attention of Monal Shah, MD. Midway through residency, he decided that the best word for it was respect. For the doctors and the people they treated—respect.

“I also liked that [the hospitalists] had a depth of knowledge outside of clinical care that was still important in managing patients: e.g. what insurance pays for what service, how to facilitate outpatient follow-up appointments, the importance of social factors in preventing a patient from returning to the hospital, etc.,” Dr. Shah says. “Even though we weren’t in an outpatient setting, I really appreciated that holistic approach and knowledge base required to care for inpatients.”

That was more than a decade ago at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. In the intervening years, Dr. Shah has become involved in clinical informatics and works with a nonprofit company developing prediction models and surveillance analytics for healthcare systems. He also serves as a physician advisor for Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas.

Question: I have your CV, but tell me a little more about your training in medical school and residency. What did you like most [and] dislike during the process? Was there a single moment you knew “I can do this”?

Answer: I really enjoyed the camaraderie of residency, especially when I was on an inpatient service and worked with a team [residents, interns, students, and attending]. I was fortunate to have an amazing group of people who inspired me to become a better clinician. I liked clinic the least. I still have days when I’m not sure if “I can do this.”

Q: What’s the biggest change you would like to see in hospital medicine?

A: With information overload, I feel like it’s pretty easy to figure out how to clinically care for a patient. For example, knowing which antibiotic to give for a certain infection is pretty easy to figure out. But knowing which IV antibiotics can/should be given in a nursing facility or at home is more nuanced and forces providers to address and think about the financial and social implications of healthcare. I think that it’s helpful for all specialties to have understanding about this, so the earlier that this type of training occurs (i.e., medical school), the better.

Q: Clinical informatics is clearly a growing area of interest for many. What about it appeals to you? How would you like to apply that knowledge to HM?

A: I found the EHR [electronic health record] to be very valuable, and it’s become difficult to imagine what it was like practicing in the pre-electronic era, but, with it, there definitely is information overload. Specifically, there is lots of duplicative/repetitive information coupled with new information (e.g. labs, vitals, imaging, notes) continuously being generated. Unless you’re sitting at the EMR [electronic medical record] or being notified every time something new appears, it’s almost impossible to know what is going on with the patient in real time. Clinical informatics has the ability to look for the most salient pieces of information—for instance, specific labs or radiology findings or specific words a clinician/nurse might use through natural language processing, etc. [We can] synthesize that information in real time to identify patients with certain diseases—like sepsis, where treatment with antibiotics is time-sensitive, or those who are at risk for adverse events. [We can identify,] for example, those patients at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest, readmission, etc.

Q: You’ve talked about access to data. How do you access the technology? How often? What about it works best for you? Is it something you wish older docs used more?

A: There is so much information ... that is constantly being generated [that] it makes it almost impossible to stay up to date on everything. Rather than even attempt to memorize every single treatment, I make an effort to know where to look for standard of care treatment regimens (e.g. ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] anticoagulation guidelines, IDSA [Infectious Diseases Society of America] guidelines, ACC/AHA [American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association] peri-operative guidelines). I use technology daily, probably looking up something on at least half of the patients I’m taking care of [on] a given day.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Being able to say no.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Students and residents that I’ve worked with who choose a career in HM.

Q: What aspect of patient care is most rewarding?

A: Seeing a patient get well enough to be discharged home or to a lower level of care.

Q: What’s the best advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to anyone asking for help in managing a patient.

Q: What’s the worst advice you ever received?

A: Say yes to every job opportunity.

Q: Did you have a mentor during training or early career? If so, who was the mentor and what were the most important lessons you learned from him/her?

A: My division chief, although he probably didn’t know it. He was firm and had a clear direction for the division/program; however, he was very affable and had a delicate touch when dealing with the other physicians.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

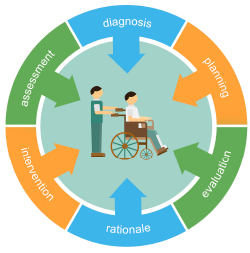

How to Initiate a VTE Quality Improvement Project

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.