User login

In the Literature

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk factors for iatrogenic pneumothorax

- Residency acceptance and use of pharmaceutical industry funding

- Early cholecystectomy outcomes for gallstone pancreatitis

- Use of microbial DNA in sepsis

- Adding rifampicin to vancomycin in MRSA pneumonia

- Rate and outcomes of culture-negative severe sepsis

- Rates of surgical comanagement in U.S. hospitals

- Probiotics and rates of ventilator-associated pneumonia

Ultrasound Guidance and Operator Experience Decrease Risk of Pneumothorax Following Thoracentesis

Clinical question: How often does pneumothorax happen following thoracentesis, and what factors are associated with increased risk of this complication?

Background: Procedural complications are an important source of adverse events in the hospital. Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis results in increased hospital length of stay, morbidity, and mortality. Large variation exists in reported pneumothorax rates, and little is known about procedure- and patient-specific factors associated with development of this complication.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Review of 24 MEDLINE-indexed studies from January 1966 to April 2009.

Synopsis: A total of 349 pneumothoraces were reported after 6,605 thoracenteses (overall incidence 6.0%). Chest-tube insertion was required in 34.1% of the cases. Risk for pneumothorax was significantly higher when larger needles or catheters were used compared with needles smaller than 20-gauge (odds ratio 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-6.0) and after therapeutic thoracentesis compared with diagnostic procedures (OR 2.6, 95% CI, 1.8-3.8).

Procedures requiring two or more needle passes did not significantly increase pneumothorax risk (OR 2.5, 95% CI, 0.3-20.1). In contrast, pneumothorax rates were significantly lower when using ultrasound guidance (OR 0.3, 95% CI, 0.2-0.7) and with experienced operators (3.9% vs. 8.5%, P=0.04).

Examining patient risk factors, pneumothorax rates were similar regardless of effusion size and patient gender. Additionally, rates were similar among non-ICU inpatients, ICU inpatients, and outpatients. Data did show a trend toward increased risk of pneumothorax with mechanical ventilation (OR 4.0, 95% CI, 0.95-16.8), although no study directly compared rates in ICU patients with and without mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Ultrasound guidance is a modifiable factor that decreases the risk of post-thoracentesis pneumothorax. Pneumothorax rates are lower when performed by experienced clinicians, providing an important opportunity to reduce procedure-related complications by increasing direct trainee supervision.

Citation: Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):332-339.

Pharmaceutical Industry Support Is Common in U.S. Internal-Medicine Residency Programs

Clinical question: What are the current attitudes of program directors regarding pharmaceutical industry support of internal-medicine residency activities? What are the potential associations between program characteristics and acceptance of industry support?

Background: Increasing evidence suggests that interactions with the pharmaceutical industry influence physician attitudes and practices. Recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) proposed that academic medical centers prohibit the acceptance of all gifts and restrict access by pharmaceutical industry representatives.

Study design: Survey of U.S. internal-medicine residency program directors.

Setting: Web-based survey of residency program directors in 388 U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 236 program directors responding to the survey, 132 (55.9%) reported accepting some kind of support from the pharmaceutical industry. Support was most commonly provided in the form of food for conferences (90.9%), educational materials (83.3%), office supplies (68.9%), and drug samples (57.6%).

When programs reported accepting pharmaceutical industry support, 67.9% cited a lack of other funding sources as the reason for acceptance. Only 22.7% of programs with a program director who thinks pharmaceutical support is unacceptable actually accepted industry support. The likelihood of accepting support was associated with location in the Southern U.S. and was inversely associated with the three-year rolling American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) pass rates (each 1% decrease in the pass rate was associated with a 21% increase in the odds of accepting pharmaceutical industry support).

Bottom line: While most program directors did not find pharmaceutical industry support desirable, more than half reported acceptance of such support, with most citing lack of other funding resources as the reason for acceptance.

Citation: Loertscher LL, Halvorsen AJ, Beasley BW, Holmboe ES, Kolars JC, McDonald FS. Pharmaceutical industry support and residency education: a survey of internal medicine program directors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):356-362.

Early Cholecystectomy Safely Decreases Hospital Stay in Patients with Mild Gallstone Pancreatitis

Clinical question: Can laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission for mild gallstone pancreatitis reduce hospital length of stay without increasing perioperative complications?

Background: Although there is a clear consensus that patients who present with gallstone pancreatitis should undergo cholecystectomy to prevent recurrence, precise timing of surgery remains controversial.

Study design: Randomized prospective trial.

Setting: Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, a Los Angeles County public teaching hospital and Level I trauma center.

Synopsis: Patients were prospectively randomized to an early group and a control group. Inclusion criteria consisted of adults from the ages of 18 to 100 with mild gallstone pancreatitis and three or fewer Ranson criteria. The primary endpoint was length of hospital stay. The secondary endpoint was a composite of complications, including the need for conversion to open cholecystectomy, readmission within 30 days, bleeding requiring transfusion, bile duct injury, or wound infection.

The study was terminated after 50 patients, as there was a difference in the length of hospital stay with a predefined alpha level of 0.005. Patients in the early group were taken to the operating room at a mean of 35.1 hours after admission, compared with 77.8 hours in the control group. The overall length of hospital stay was shorter in the early group (mean 3.5 days, 95% CI, 2.7-4.3), compared with the control group (mean 5.8, 95% CI, 3.8-7.9). All cholecystectomies were completed laparoscopically, without conversion to open. No statistically significant difference existed in secondary endpoints (P=0.48, OR 1.66, 95% CI, 0.41-6.78).

Bottom line: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission, irrespective of normalization of laboratory values or clinical progress, safely decreases the overall length of stay, compared with delaying laparoscopic cholecystectomy until laboratory values and clinical condition normalize.

Citation: Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4): 615-619.

Presence of Microbial DNA in Blood Correlates with Disease Severity

Clinical question: Is the presence of microbial DNA in the blood associated with disease severity in severe sepsis, and how does detection of this microbial DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) compare with blood cultures (BC)?

Background: Inadequate antibiotic therapy is a strong and independent predictor of poor outcomes in sepsis. Diagnostic uncertainty regarding the causative micro-organism is compensated for by liberal use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. As a result, resistance to antibiotics is an increasing public-health problem.

Study design: Prospective multicenter controlled observational study.

Setting: Three ICUs in Germany and France.

Synopsis: From 2005 to 2007, 63 patients were enrolled in the control group and 142 patients were enrolled in the sepsis group. In control patients, blood cultures and specimens were drawn daily at a maximum of three days after admission. In the sepsis group, blood samples were obtained on the day severe sepsis was suspected. Consecutive samples for the next two days after study inclusion were taken.

Taking BC as the laboratory comparison method, the sensitivity of PCR to detect culture-positive bacteremia in sepsis was 0.80 with a specificity of 0.77. PCR detected 29 of 41 microorganisms (70.3%) found in the BC. The highest recovery rate was observed for gram-negative bacteria (78.6%), fungi (50.0%), and gram-positive bacteria (47.6%). PCR from septic patients correlated well with markers of host response (IL-6 and PCT) and disease severity (SOFA score), even when the BC remained negative.

The appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy based on culture-based methods was not recorded, so it’s impossible to conclude whether or not the PCR would have contributed to a more effective therapy.

Bottom line: Concordance between BC and PCR is moderate in septic patients. PCR-based pathogen detection correlated with disease severity even if the BC remained negative, suggesting that the presence of microbial DNA in the bloodstream is a clinically significant event.

Citation: Bloos F, Hinder F, Becker K, et al. A multicenter trial to compare blood culture with polymerase chain reaction in severe human sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):241-247.

Adding Rifampicin to Vancomycin Improves Outcomes in MRSA Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does adding rifampicin to vancomycin improve outcomes in patients with hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia?

Background: Hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia has a mortality of more than 20%. Vancomycin penetrates the lung tissue poorly. The value of adding rifampicin, an antibiotic with broad-spectrum coverage and good tissue penetration, was investigated.

Study design: Randomized open-label trial.

Setting: Medical ICU patients at Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, South Korea.

Synopsis: Patients older than 18 years of age with clinical symptoms suggestive of nosocomial pneumonia were randomized to receive vancomycin alone (V) or vancomycin plus rifampicin (VR). Clinicians could add additional antibiotics for gram-negative coverage as needed.

Of the 183 patients screened, 93 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized in a 1:1 ratio. MRSA infection was microbiologically confirmed. Clinical cure rate in VR patients was significantly greater at day 14 compared with the V group (53.7% vs. 31.0%, P=0.047) based on a modified intention-to-treat model. The overall mortality at day 28 did not significantly differ between the groups (22.0% vs. 38.1%, P=0.15), although the 60-day mortality was lower in the VR group (26.8% vs. 50.0%, P=0.042). Mortality from MRSA pneumonia had a trend toward a decrease in the VR group (14.7% vs. 28.6%, P=0.18).

The trial was limited because it was a single-site study and lacked statistical power to assess certain outcomes. Additionally, treatment protocols were not compared with other antimicrobial therapies.

Bottom line: Vancomycin plus rifampicin improves MRSA pneumonia outcomes in ICU patients.

Citation: Jung YJ, Koh Y, Hong SB, et al. Effect of vancomycin plus rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial MRSA pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):175-180.

Severe Sepsis Syndromes Are Not Always Caused by Bacteremia

Clinical question: What are the common causes of clinical sepsis?

Background: When sepsis is defined by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the etiology is not always infectious. Rapid initiation of antimicrobial therapy for infectious SIRS is a priority, but it could result in treating a significant number of patients who are not bacteremic.

Study design: Prospective secondary analysis of a registry of patients created to evaluate an institutional standard-of-care protocol.

Setting: Urban, 850-bed, tertiary-care teaching institution in North Carolina.

Synopsis: ED cases meeting the criteria for severe sepsis underwent a secondary review that looked at the cause of the sepsis. Only 45% of patients identified as having severe sepsis were blood-culture-positive during that episode of care. The culture-positive group was more likely to have central lines, malignancies, or reside in a nursing home.

Of the subgroup of culture-negative patients, 52% had another infectious etiology, most commonly pneumonia. Other “noninfectious mimics,” including inflammatory colitis, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism, were noted in 32% of patients in the subgroup, and the cause was not identified in 16% of the patients.

In-hospital mortality was higher in the culture-positive group than in the culture-negative group (25% vs. 4%, P=0.05). There was no evidence of harm in patients with culture-negative sepsis treated for a systemic infection.

Bottom line: Many patients with a clinical picture of severe sepsis will not have positive blood cultures or an infectious etiology.

Citation: Heffner AC, Horton JM, Marchick MR, Jones AE. Etiology of illness in patients with severe sepsis admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):814-820.

Comanagement of Surgical Inpatients by Hospitalists Is Rapidly Expanding

Clinical question: What is the prevalence and nature of comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians?

Background: Comanagement of surgical patients is a common clinical role for hospitalists, but the relationship is not well characterized in the literature in terms of numbers of patients or types of physicians involved in this practice.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Cross-section of hospitals from a Medicare database.

Synopsis: During the study period, 35.2% of patients were comanaged by a medicine physician—23.7% by a generalist and 14% by a subspecialist. Cardiothoracic surgery patients were more likely to be comanaged by a subspecialist, whereas all other patients were more likely to be comanaged by a generalist.

Although subspecialist comanagement actually declined during the study period, overall comanagement increased from 33.3% in 1996 to 40.8% in 2006. This increase is entirely attributable to the increase in comanagement by hospitalists. Most of this growth occurred with orthopedic patients.

Patient factors associated with comanagement include advanced age, emergency admissions, and increasing comorbidities. Teaching hospitals had less comanagement, while midsize, nonteaching, and for-profit hospitals had more comanagement.

Bottom line: Comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians is a common and growing clinical relationship. Hospitalists are responsible for increasing numbers of comanaged surgical patients.

Citation: Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368.

Probiotics Might Decrease Risk of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does the administration of probiotics decrease the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients?

Background: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a major nosocomial infection in ICUs. Probiotics are thought to decrease colonization and, therefore, infection with serious hospital-acquired pathogens.

Study design: Meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials.

Setting: ICU patients on mechanical ventilation for at least 24 hours.

Synopsis: Five trials met the inclusion criteria of comparing probiotics to placebo in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation and reporting the outcome of VAP. Administration of probiotics decreased the incidence of VAP (odds ratio 0.61, 95% CI, 0.41-0.91) and colonization of the respiratory tract with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (OR 0.35, 95% CI, 0.13-0.93).

Length of ICU stay was decreased in the probiotic arm, although this effect was not statistically significant in all analyses. Probiotics had no effect on such outcomes as ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, or duration of mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Probiotics might be an effective strategy to reduce the risk of VAP, even if they do not appear to impact such outcomes as mortality.

Citation: Siempos II, Ntaidou TK, Falagas ME. Impact of the administration of probiotics on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):954-962. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk factors for iatrogenic pneumothorax

- Residency acceptance and use of pharmaceutical industry funding

- Early cholecystectomy outcomes for gallstone pancreatitis

- Use of microbial DNA in sepsis

- Adding rifampicin to vancomycin in MRSA pneumonia

- Rate and outcomes of culture-negative severe sepsis

- Rates of surgical comanagement in U.S. hospitals

- Probiotics and rates of ventilator-associated pneumonia

Ultrasound Guidance and Operator Experience Decrease Risk of Pneumothorax Following Thoracentesis

Clinical question: How often does pneumothorax happen following thoracentesis, and what factors are associated with increased risk of this complication?

Background: Procedural complications are an important source of adverse events in the hospital. Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis results in increased hospital length of stay, morbidity, and mortality. Large variation exists in reported pneumothorax rates, and little is known about procedure- and patient-specific factors associated with development of this complication.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Review of 24 MEDLINE-indexed studies from January 1966 to April 2009.

Synopsis: A total of 349 pneumothoraces were reported after 6,605 thoracenteses (overall incidence 6.0%). Chest-tube insertion was required in 34.1% of the cases. Risk for pneumothorax was significantly higher when larger needles or catheters were used compared with needles smaller than 20-gauge (odds ratio 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-6.0) and after therapeutic thoracentesis compared with diagnostic procedures (OR 2.6, 95% CI, 1.8-3.8).

Procedures requiring two or more needle passes did not significantly increase pneumothorax risk (OR 2.5, 95% CI, 0.3-20.1). In contrast, pneumothorax rates were significantly lower when using ultrasound guidance (OR 0.3, 95% CI, 0.2-0.7) and with experienced operators (3.9% vs. 8.5%, P=0.04).

Examining patient risk factors, pneumothorax rates were similar regardless of effusion size and patient gender. Additionally, rates were similar among non-ICU inpatients, ICU inpatients, and outpatients. Data did show a trend toward increased risk of pneumothorax with mechanical ventilation (OR 4.0, 95% CI, 0.95-16.8), although no study directly compared rates in ICU patients with and without mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Ultrasound guidance is a modifiable factor that decreases the risk of post-thoracentesis pneumothorax. Pneumothorax rates are lower when performed by experienced clinicians, providing an important opportunity to reduce procedure-related complications by increasing direct trainee supervision.

Citation: Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):332-339.

Pharmaceutical Industry Support Is Common in U.S. Internal-Medicine Residency Programs

Clinical question: What are the current attitudes of program directors regarding pharmaceutical industry support of internal-medicine residency activities? What are the potential associations between program characteristics and acceptance of industry support?

Background: Increasing evidence suggests that interactions with the pharmaceutical industry influence physician attitudes and practices. Recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) proposed that academic medical centers prohibit the acceptance of all gifts and restrict access by pharmaceutical industry representatives.

Study design: Survey of U.S. internal-medicine residency program directors.

Setting: Web-based survey of residency program directors in 388 U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 236 program directors responding to the survey, 132 (55.9%) reported accepting some kind of support from the pharmaceutical industry. Support was most commonly provided in the form of food for conferences (90.9%), educational materials (83.3%), office supplies (68.9%), and drug samples (57.6%).

When programs reported accepting pharmaceutical industry support, 67.9% cited a lack of other funding sources as the reason for acceptance. Only 22.7% of programs with a program director who thinks pharmaceutical support is unacceptable actually accepted industry support. The likelihood of accepting support was associated with location in the Southern U.S. and was inversely associated with the three-year rolling American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) pass rates (each 1% decrease in the pass rate was associated with a 21% increase in the odds of accepting pharmaceutical industry support).

Bottom line: While most program directors did not find pharmaceutical industry support desirable, more than half reported acceptance of such support, with most citing lack of other funding resources as the reason for acceptance.

Citation: Loertscher LL, Halvorsen AJ, Beasley BW, Holmboe ES, Kolars JC, McDonald FS. Pharmaceutical industry support and residency education: a survey of internal medicine program directors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):356-362.

Early Cholecystectomy Safely Decreases Hospital Stay in Patients with Mild Gallstone Pancreatitis

Clinical question: Can laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission for mild gallstone pancreatitis reduce hospital length of stay without increasing perioperative complications?

Background: Although there is a clear consensus that patients who present with gallstone pancreatitis should undergo cholecystectomy to prevent recurrence, precise timing of surgery remains controversial.

Study design: Randomized prospective trial.

Setting: Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, a Los Angeles County public teaching hospital and Level I trauma center.

Synopsis: Patients were prospectively randomized to an early group and a control group. Inclusion criteria consisted of adults from the ages of 18 to 100 with mild gallstone pancreatitis and three or fewer Ranson criteria. The primary endpoint was length of hospital stay. The secondary endpoint was a composite of complications, including the need for conversion to open cholecystectomy, readmission within 30 days, bleeding requiring transfusion, bile duct injury, or wound infection.

The study was terminated after 50 patients, as there was a difference in the length of hospital stay with a predefined alpha level of 0.005. Patients in the early group were taken to the operating room at a mean of 35.1 hours after admission, compared with 77.8 hours in the control group. The overall length of hospital stay was shorter in the early group (mean 3.5 days, 95% CI, 2.7-4.3), compared with the control group (mean 5.8, 95% CI, 3.8-7.9). All cholecystectomies were completed laparoscopically, without conversion to open. No statistically significant difference existed in secondary endpoints (P=0.48, OR 1.66, 95% CI, 0.41-6.78).

Bottom line: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission, irrespective of normalization of laboratory values or clinical progress, safely decreases the overall length of stay, compared with delaying laparoscopic cholecystectomy until laboratory values and clinical condition normalize.

Citation: Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4): 615-619.

Presence of Microbial DNA in Blood Correlates with Disease Severity

Clinical question: Is the presence of microbial DNA in the blood associated with disease severity in severe sepsis, and how does detection of this microbial DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) compare with blood cultures (BC)?

Background: Inadequate antibiotic therapy is a strong and independent predictor of poor outcomes in sepsis. Diagnostic uncertainty regarding the causative micro-organism is compensated for by liberal use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. As a result, resistance to antibiotics is an increasing public-health problem.

Study design: Prospective multicenter controlled observational study.

Setting: Three ICUs in Germany and France.

Synopsis: From 2005 to 2007, 63 patients were enrolled in the control group and 142 patients were enrolled in the sepsis group. In control patients, blood cultures and specimens were drawn daily at a maximum of three days after admission. In the sepsis group, blood samples were obtained on the day severe sepsis was suspected. Consecutive samples for the next two days after study inclusion were taken.

Taking BC as the laboratory comparison method, the sensitivity of PCR to detect culture-positive bacteremia in sepsis was 0.80 with a specificity of 0.77. PCR detected 29 of 41 microorganisms (70.3%) found in the BC. The highest recovery rate was observed for gram-negative bacteria (78.6%), fungi (50.0%), and gram-positive bacteria (47.6%). PCR from septic patients correlated well with markers of host response (IL-6 and PCT) and disease severity (SOFA score), even when the BC remained negative.

The appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy based on culture-based methods was not recorded, so it’s impossible to conclude whether or not the PCR would have contributed to a more effective therapy.

Bottom line: Concordance between BC and PCR is moderate in septic patients. PCR-based pathogen detection correlated with disease severity even if the BC remained negative, suggesting that the presence of microbial DNA in the bloodstream is a clinically significant event.

Citation: Bloos F, Hinder F, Becker K, et al. A multicenter trial to compare blood culture with polymerase chain reaction in severe human sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):241-247.

Adding Rifampicin to Vancomycin Improves Outcomes in MRSA Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does adding rifampicin to vancomycin improve outcomes in patients with hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia?

Background: Hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia has a mortality of more than 20%. Vancomycin penetrates the lung tissue poorly. The value of adding rifampicin, an antibiotic with broad-spectrum coverage and good tissue penetration, was investigated.

Study design: Randomized open-label trial.

Setting: Medical ICU patients at Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, South Korea.

Synopsis: Patients older than 18 years of age with clinical symptoms suggestive of nosocomial pneumonia were randomized to receive vancomycin alone (V) or vancomycin plus rifampicin (VR). Clinicians could add additional antibiotics for gram-negative coverage as needed.

Of the 183 patients screened, 93 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized in a 1:1 ratio. MRSA infection was microbiologically confirmed. Clinical cure rate in VR patients was significantly greater at day 14 compared with the V group (53.7% vs. 31.0%, P=0.047) based on a modified intention-to-treat model. The overall mortality at day 28 did not significantly differ between the groups (22.0% vs. 38.1%, P=0.15), although the 60-day mortality was lower in the VR group (26.8% vs. 50.0%, P=0.042). Mortality from MRSA pneumonia had a trend toward a decrease in the VR group (14.7% vs. 28.6%, P=0.18).

The trial was limited because it was a single-site study and lacked statistical power to assess certain outcomes. Additionally, treatment protocols were not compared with other antimicrobial therapies.

Bottom line: Vancomycin plus rifampicin improves MRSA pneumonia outcomes in ICU patients.

Citation: Jung YJ, Koh Y, Hong SB, et al. Effect of vancomycin plus rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial MRSA pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):175-180.

Severe Sepsis Syndromes Are Not Always Caused by Bacteremia

Clinical question: What are the common causes of clinical sepsis?

Background: When sepsis is defined by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the etiology is not always infectious. Rapid initiation of antimicrobial therapy for infectious SIRS is a priority, but it could result in treating a significant number of patients who are not bacteremic.

Study design: Prospective secondary analysis of a registry of patients created to evaluate an institutional standard-of-care protocol.

Setting: Urban, 850-bed, tertiary-care teaching institution in North Carolina.

Synopsis: ED cases meeting the criteria for severe sepsis underwent a secondary review that looked at the cause of the sepsis. Only 45% of patients identified as having severe sepsis were blood-culture-positive during that episode of care. The culture-positive group was more likely to have central lines, malignancies, or reside in a nursing home.

Of the subgroup of culture-negative patients, 52% had another infectious etiology, most commonly pneumonia. Other “noninfectious mimics,” including inflammatory colitis, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism, were noted in 32% of patients in the subgroup, and the cause was not identified in 16% of the patients.

In-hospital mortality was higher in the culture-positive group than in the culture-negative group (25% vs. 4%, P=0.05). There was no evidence of harm in patients with culture-negative sepsis treated for a systemic infection.

Bottom line: Many patients with a clinical picture of severe sepsis will not have positive blood cultures or an infectious etiology.

Citation: Heffner AC, Horton JM, Marchick MR, Jones AE. Etiology of illness in patients with severe sepsis admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):814-820.

Comanagement of Surgical Inpatients by Hospitalists Is Rapidly Expanding

Clinical question: What is the prevalence and nature of comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians?

Background: Comanagement of surgical patients is a common clinical role for hospitalists, but the relationship is not well characterized in the literature in terms of numbers of patients or types of physicians involved in this practice.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Cross-section of hospitals from a Medicare database.

Synopsis: During the study period, 35.2% of patients were comanaged by a medicine physician—23.7% by a generalist and 14% by a subspecialist. Cardiothoracic surgery patients were more likely to be comanaged by a subspecialist, whereas all other patients were more likely to be comanaged by a generalist.

Although subspecialist comanagement actually declined during the study period, overall comanagement increased from 33.3% in 1996 to 40.8% in 2006. This increase is entirely attributable to the increase in comanagement by hospitalists. Most of this growth occurred with orthopedic patients.

Patient factors associated with comanagement include advanced age, emergency admissions, and increasing comorbidities. Teaching hospitals had less comanagement, while midsize, nonteaching, and for-profit hospitals had more comanagement.

Bottom line: Comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians is a common and growing clinical relationship. Hospitalists are responsible for increasing numbers of comanaged surgical patients.

Citation: Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368.

Probiotics Might Decrease Risk of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does the administration of probiotics decrease the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients?

Background: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a major nosocomial infection in ICUs. Probiotics are thought to decrease colonization and, therefore, infection with serious hospital-acquired pathogens.

Study design: Meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials.

Setting: ICU patients on mechanical ventilation for at least 24 hours.

Synopsis: Five trials met the inclusion criteria of comparing probiotics to placebo in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation and reporting the outcome of VAP. Administration of probiotics decreased the incidence of VAP (odds ratio 0.61, 95% CI, 0.41-0.91) and colonization of the respiratory tract with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (OR 0.35, 95% CI, 0.13-0.93).

Length of ICU stay was decreased in the probiotic arm, although this effect was not statistically significant in all analyses. Probiotics had no effect on such outcomes as ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, or duration of mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Probiotics might be an effective strategy to reduce the risk of VAP, even if they do not appear to impact such outcomes as mortality.

Citation: Siempos II, Ntaidou TK, Falagas ME. Impact of the administration of probiotics on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):954-962. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Risk factors for iatrogenic pneumothorax

- Residency acceptance and use of pharmaceutical industry funding

- Early cholecystectomy outcomes for gallstone pancreatitis

- Use of microbial DNA in sepsis

- Adding rifampicin to vancomycin in MRSA pneumonia

- Rate and outcomes of culture-negative severe sepsis

- Rates of surgical comanagement in U.S. hospitals

- Probiotics and rates of ventilator-associated pneumonia

Ultrasound Guidance and Operator Experience Decrease Risk of Pneumothorax Following Thoracentesis

Clinical question: How often does pneumothorax happen following thoracentesis, and what factors are associated with increased risk of this complication?

Background: Procedural complications are an important source of adverse events in the hospital. Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis results in increased hospital length of stay, morbidity, and mortality. Large variation exists in reported pneumothorax rates, and little is known about procedure- and patient-specific factors associated with development of this complication.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Review of 24 MEDLINE-indexed studies from January 1966 to April 2009.

Synopsis: A total of 349 pneumothoraces were reported after 6,605 thoracenteses (overall incidence 6.0%). Chest-tube insertion was required in 34.1% of the cases. Risk for pneumothorax was significantly higher when larger needles or catheters were used compared with needles smaller than 20-gauge (odds ratio 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-6.0) and after therapeutic thoracentesis compared with diagnostic procedures (OR 2.6, 95% CI, 1.8-3.8).

Procedures requiring two or more needle passes did not significantly increase pneumothorax risk (OR 2.5, 95% CI, 0.3-20.1). In contrast, pneumothorax rates were significantly lower when using ultrasound guidance (OR 0.3, 95% CI, 0.2-0.7) and with experienced operators (3.9% vs. 8.5%, P=0.04).

Examining patient risk factors, pneumothorax rates were similar regardless of effusion size and patient gender. Additionally, rates were similar among non-ICU inpatients, ICU inpatients, and outpatients. Data did show a trend toward increased risk of pneumothorax with mechanical ventilation (OR 4.0, 95% CI, 0.95-16.8), although no study directly compared rates in ICU patients with and without mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Ultrasound guidance is a modifiable factor that decreases the risk of post-thoracentesis pneumothorax. Pneumothorax rates are lower when performed by experienced clinicians, providing an important opportunity to reduce procedure-related complications by increasing direct trainee supervision.

Citation: Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):332-339.

Pharmaceutical Industry Support Is Common in U.S. Internal-Medicine Residency Programs

Clinical question: What are the current attitudes of program directors regarding pharmaceutical industry support of internal-medicine residency activities? What are the potential associations between program characteristics and acceptance of industry support?

Background: Increasing evidence suggests that interactions with the pharmaceutical industry influence physician attitudes and practices. Recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) proposed that academic medical centers prohibit the acceptance of all gifts and restrict access by pharmaceutical industry representatives.

Study design: Survey of U.S. internal-medicine residency program directors.

Setting: Web-based survey of residency program directors in 388 U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 236 program directors responding to the survey, 132 (55.9%) reported accepting some kind of support from the pharmaceutical industry. Support was most commonly provided in the form of food for conferences (90.9%), educational materials (83.3%), office supplies (68.9%), and drug samples (57.6%).

When programs reported accepting pharmaceutical industry support, 67.9% cited a lack of other funding sources as the reason for acceptance. Only 22.7% of programs with a program director who thinks pharmaceutical support is unacceptable actually accepted industry support. The likelihood of accepting support was associated with location in the Southern U.S. and was inversely associated with the three-year rolling American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) pass rates (each 1% decrease in the pass rate was associated with a 21% increase in the odds of accepting pharmaceutical industry support).

Bottom line: While most program directors did not find pharmaceutical industry support desirable, more than half reported acceptance of such support, with most citing lack of other funding resources as the reason for acceptance.

Citation: Loertscher LL, Halvorsen AJ, Beasley BW, Holmboe ES, Kolars JC, McDonald FS. Pharmaceutical industry support and residency education: a survey of internal medicine program directors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):356-362.

Early Cholecystectomy Safely Decreases Hospital Stay in Patients with Mild Gallstone Pancreatitis

Clinical question: Can laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission for mild gallstone pancreatitis reduce hospital length of stay without increasing perioperative complications?

Background: Although there is a clear consensus that patients who present with gallstone pancreatitis should undergo cholecystectomy to prevent recurrence, precise timing of surgery remains controversial.

Study design: Randomized prospective trial.

Setting: Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, a Los Angeles County public teaching hospital and Level I trauma center.

Synopsis: Patients were prospectively randomized to an early group and a control group. Inclusion criteria consisted of adults from the ages of 18 to 100 with mild gallstone pancreatitis and three or fewer Ranson criteria. The primary endpoint was length of hospital stay. The secondary endpoint was a composite of complications, including the need for conversion to open cholecystectomy, readmission within 30 days, bleeding requiring transfusion, bile duct injury, or wound infection.

The study was terminated after 50 patients, as there was a difference in the length of hospital stay with a predefined alpha level of 0.005. Patients in the early group were taken to the operating room at a mean of 35.1 hours after admission, compared with 77.8 hours in the control group. The overall length of hospital stay was shorter in the early group (mean 3.5 days, 95% CI, 2.7-4.3), compared with the control group (mean 5.8, 95% CI, 3.8-7.9). All cholecystectomies were completed laparoscopically, without conversion to open. No statistically significant difference existed in secondary endpoints (P=0.48, OR 1.66, 95% CI, 0.41-6.78).

Bottom line: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission, irrespective of normalization of laboratory values or clinical progress, safely decreases the overall length of stay, compared with delaying laparoscopic cholecystectomy until laboratory values and clinical condition normalize.

Citation: Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4): 615-619.

Presence of Microbial DNA in Blood Correlates with Disease Severity

Clinical question: Is the presence of microbial DNA in the blood associated with disease severity in severe sepsis, and how does detection of this microbial DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) compare with blood cultures (BC)?

Background: Inadequate antibiotic therapy is a strong and independent predictor of poor outcomes in sepsis. Diagnostic uncertainty regarding the causative micro-organism is compensated for by liberal use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. As a result, resistance to antibiotics is an increasing public-health problem.

Study design: Prospective multicenter controlled observational study.

Setting: Three ICUs in Germany and France.

Synopsis: From 2005 to 2007, 63 patients were enrolled in the control group and 142 patients were enrolled in the sepsis group. In control patients, blood cultures and specimens were drawn daily at a maximum of three days after admission. In the sepsis group, blood samples were obtained on the day severe sepsis was suspected. Consecutive samples for the next two days after study inclusion were taken.

Taking BC as the laboratory comparison method, the sensitivity of PCR to detect culture-positive bacteremia in sepsis was 0.80 with a specificity of 0.77. PCR detected 29 of 41 microorganisms (70.3%) found in the BC. The highest recovery rate was observed for gram-negative bacteria (78.6%), fungi (50.0%), and gram-positive bacteria (47.6%). PCR from septic patients correlated well with markers of host response (IL-6 and PCT) and disease severity (SOFA score), even when the BC remained negative.

The appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy based on culture-based methods was not recorded, so it’s impossible to conclude whether or not the PCR would have contributed to a more effective therapy.

Bottom line: Concordance between BC and PCR is moderate in septic patients. PCR-based pathogen detection correlated with disease severity even if the BC remained negative, suggesting that the presence of microbial DNA in the bloodstream is a clinically significant event.

Citation: Bloos F, Hinder F, Becker K, et al. A multicenter trial to compare blood culture with polymerase chain reaction in severe human sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):241-247.

Adding Rifampicin to Vancomycin Improves Outcomes in MRSA Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does adding rifampicin to vancomycin improve outcomes in patients with hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia?

Background: Hospital-acquired MRSA pneumonia has a mortality of more than 20%. Vancomycin penetrates the lung tissue poorly. The value of adding rifampicin, an antibiotic with broad-spectrum coverage and good tissue penetration, was investigated.

Study design: Randomized open-label trial.

Setting: Medical ICU patients at Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, South Korea.

Synopsis: Patients older than 18 years of age with clinical symptoms suggestive of nosocomial pneumonia were randomized to receive vancomycin alone (V) or vancomycin plus rifampicin (VR). Clinicians could add additional antibiotics for gram-negative coverage as needed.

Of the 183 patients screened, 93 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized in a 1:1 ratio. MRSA infection was microbiologically confirmed. Clinical cure rate in VR patients was significantly greater at day 14 compared with the V group (53.7% vs. 31.0%, P=0.047) based on a modified intention-to-treat model. The overall mortality at day 28 did not significantly differ between the groups (22.0% vs. 38.1%, P=0.15), although the 60-day mortality was lower in the VR group (26.8% vs. 50.0%, P=0.042). Mortality from MRSA pneumonia had a trend toward a decrease in the VR group (14.7% vs. 28.6%, P=0.18).

The trial was limited because it was a single-site study and lacked statistical power to assess certain outcomes. Additionally, treatment protocols were not compared with other antimicrobial therapies.

Bottom line: Vancomycin plus rifampicin improves MRSA pneumonia outcomes in ICU patients.

Citation: Jung YJ, Koh Y, Hong SB, et al. Effect of vancomycin plus rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial MRSA pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):175-180.

Severe Sepsis Syndromes Are Not Always Caused by Bacteremia

Clinical question: What are the common causes of clinical sepsis?

Background: When sepsis is defined by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the etiology is not always infectious. Rapid initiation of antimicrobial therapy for infectious SIRS is a priority, but it could result in treating a significant number of patients who are not bacteremic.

Study design: Prospective secondary analysis of a registry of patients created to evaluate an institutional standard-of-care protocol.

Setting: Urban, 850-bed, tertiary-care teaching institution in North Carolina.

Synopsis: ED cases meeting the criteria for severe sepsis underwent a secondary review that looked at the cause of the sepsis. Only 45% of patients identified as having severe sepsis were blood-culture-positive during that episode of care. The culture-positive group was more likely to have central lines, malignancies, or reside in a nursing home.

Of the subgroup of culture-negative patients, 52% had another infectious etiology, most commonly pneumonia. Other “noninfectious mimics,” including inflammatory colitis, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism, were noted in 32% of patients in the subgroup, and the cause was not identified in 16% of the patients.

In-hospital mortality was higher in the culture-positive group than in the culture-negative group (25% vs. 4%, P=0.05). There was no evidence of harm in patients with culture-negative sepsis treated for a systemic infection.

Bottom line: Many patients with a clinical picture of severe sepsis will not have positive blood cultures or an infectious etiology.

Citation: Heffner AC, Horton JM, Marchick MR, Jones AE. Etiology of illness in patients with severe sepsis admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):814-820.

Comanagement of Surgical Inpatients by Hospitalists Is Rapidly Expanding

Clinical question: What is the prevalence and nature of comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians?

Background: Comanagement of surgical patients is a common clinical role for hospitalists, but the relationship is not well characterized in the literature in terms of numbers of patients or types of physicians involved in this practice.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Cross-section of hospitals from a Medicare database.

Synopsis: During the study period, 35.2% of patients were comanaged by a medicine physician—23.7% by a generalist and 14% by a subspecialist. Cardiothoracic surgery patients were more likely to be comanaged by a subspecialist, whereas all other patients were more likely to be comanaged by a generalist.

Although subspecialist comanagement actually declined during the study period, overall comanagement increased from 33.3% in 1996 to 40.8% in 2006. This increase is entirely attributable to the increase in comanagement by hospitalists. Most of this growth occurred with orthopedic patients.

Patient factors associated with comanagement include advanced age, emergency admissions, and increasing comorbidities. Teaching hospitals had less comanagement, while midsize, nonteaching, and for-profit hospitals had more comanagement.

Bottom line: Comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians is a common and growing clinical relationship. Hospitalists are responsible for increasing numbers of comanaged surgical patients.

Citation: Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368.

Probiotics Might Decrease Risk of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does the administration of probiotics decrease the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients?

Background: Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a major nosocomial infection in ICUs. Probiotics are thought to decrease colonization and, therefore, infection with serious hospital-acquired pathogens.

Study design: Meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials.

Setting: ICU patients on mechanical ventilation for at least 24 hours.

Synopsis: Five trials met the inclusion criteria of comparing probiotics to placebo in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation and reporting the outcome of VAP. Administration of probiotics decreased the incidence of VAP (odds ratio 0.61, 95% CI, 0.41-0.91) and colonization of the respiratory tract with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (OR 0.35, 95% CI, 0.13-0.93).

Length of ICU stay was decreased in the probiotic arm, although this effect was not statistically significant in all analyses. Probiotics had no effect on such outcomes as ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, or duration of mechanical ventilation.

Bottom line: Probiotics might be an effective strategy to reduce the risk of VAP, even if they do not appear to impact such outcomes as mortality.

Citation: Siempos II, Ntaidou TK, Falagas ME. Impact of the administration of probiotics on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):954-962. TH

How Should Hypertensive Emergencies Be Managed?

Case

A 57-year-old male with hypertension and end-stage renal disease is brought into the ED by his family for evaluation of headache, nausea, blurry vision, and confusion. Blood pressure is 235/130 mmHg. He is somnolent but arousable and oriented only to person; the remainder of his neurologic exam is nonfocal. A fundoscopic exam shows retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and papilledema. How should this patient be managed?

Overview

Hypertension (HTN) is a medical problem that affects an estimated 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. and more than 1 billion people worldwide. The Joint National Committee (JNC) 7 Report defines hypertensive emergency as severe hypertension with evidence of impending or progressive end-organ dysfunction.1 Systolic blood pressure (SBP) in these settings often is >180 mm Hg with diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >120 mm Hg. The JNC 7 Report defines hypertensive urgency as severe HTN without acute end-organ dysfunction. Whereas hypertensive urgencies can be treated with oral antihypertensive agents with close outpatient follow-up, hypertensive emergencies require immediate BP reduction to halt the progression of end-organ damage.

Severe HTN causes shear stress and endothelial injury, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade, fibrinoid necrosis, and tissue ischemia.2 Due to adaptive vascular changes, pre-existing hypertension lowers the probability of a hypertensive emergency developing at a particular BP. The rate of BP rise, rather than the absolute level, determines most end-organ damage.3 In previously normotensive patients, end-organ damage can occur at BPs >160/100 mm Hg; however, organ dysfunction is uncommon in chronically hypertensive individuals, unless BP >220/120 mm Hg.

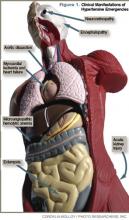

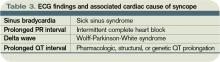

Clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergency depend on the target organs involved (see Figure 1, right). When a patient presents with severe hypertension, a focused evaluation should attempt to identify the presence of end-organ damage. If present, these patients should be admitted to an ICU for close monitoring, and administration of parenteral antihypertensive agents should be started. (Online Exclusive: View a chart of “Parenteral Antihypertensive Agents Used in Hypertensive Emergencies”)

Review of the Data

General principles: The initial therapeutic goal in most hypertensive emergencies is to reduce the mean arterial pressure (MAP) by no more than 25% within the first hour. Precipitous or excessive decreases in BP might worsen renal, cerebral, or coronary ischemia. Due to pressure natriuresis, patients with primary malignant hypertension might be volume-depleted. Restoration of intravascular volume with intravenous (IV) saline can prevent precipitous falls in BP when antihypertensive agents are started.

After the patient stabilizes, the BP can be lowered about 10% per hour to 160/100-110 mm Hg. A gradual reduction to the patient’s baseline BP is targeted over the ensuing 24 to 48 hours. Once there is stable BP control and end-organ damage has ceased, patients can be transitioned to oral therapy.

No large clinical trials have investigated optimal drug therapy in patients with hypertensive emergencies. The choice of pharmacologic agent should be individualized based on drug properties, patient comorbidities, and the end-organ(s) involved.

Selected pharmacologic agents: Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is a short-acting, potent arterial and venous dilator that has been used extensively in the treatment of hypertensive emergencies. Despite its familiarity, there are several important limitations to its use. SNP can increase intracranial pressure (ICP), worsen myocardial ischemia through coronary steal, and is associated with cyanide and/or thiocyanate toxicity. Although used broadly across many types of hypertensive emergencies, SNP should be considered a first-line agent in acute left ventricular (LV) failure and, when combined with beta-blockers, in acute aortic dissection.

Labetalol is an alpha-1 and nonselective beta-blocker that reduces systemic vascular resistance while preserving cerebral, renal, and coronary blood flow. It is considered a first-line agent in most hypertensive emergencies, with the exception of acute LV failure.

Esmolol is a short-acting, selective beta-blocker that decreases heart rate, myocardial contractility, and cardiac output.

Nicardipine is a second-generation dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker. Although it has a longer duration of action, excess hypotension has not been seen in clinical trials comparing it with SNP.4 Nicardipine is used safely in such hypertensive emergencies as hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral vascular accidents, and postoperatively.

Fenoldopam creates vasodilation by acting on peripheral dopamine type 1 receptors. It improves creatinine clearance and urine output, and is most useful in acute kidney injury.5 It is a well-tolerated and highly effective agent for use in most hypertensive crises, although is expensive and has limited hard outcome data.

Nitroglycerin is a potent venodilator that is used as an adjunct to other anti-hypertensives in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes and acute pulmonary edema.

Immediate-release nifedipine and clonidine are not recommended; they are long-acting and poorly titratable, with unpredictable hypotensive effects.

Hydralazine may be used in LV failure and in pregnancy.

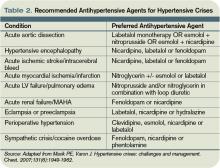

Specific emergencies: Aortic dissection is the most rapidly fatal complication of severe HTN. Untreated, approximately 80% of patients with acute type-A dissections die within two weeks.6 In this specific setting, SBP should be decreased as rapidly as possible to <110 mm Hg in order to halt propagation of the dissection prior to surgery. Therapy should aim to reduce the shear stress on the aortic wall by decreasing both BP and heart rate. This can be accomplished with a combination of esmolol and SNP. Nicardipine and fenoldopam are effective alternatives to SNP. Labetalol is a good single-agent option, provided adequate heart rate suppression is achieved.

LV failure and acute pulmonary edema are associated with high systemic vascular resistance and activation of the Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone (RAAS) system. First-line therapy should consist of arterial vasodilators (e.g., SNP, nicardipine, fenoldopam) in combination with a loop diuretic. Nitroglycerin can be used as an adjunct to reduce LV preload.

In hypertensive encephalopathy, blood pressure exceeds the cerebral autoregulatory threshold, leading to breakthrough vasodilation and the development of cerebral edema. Characteristic symptoms include the insidious onset of headache, nausea, vomiting, and nonlocalizing neurologic signs (e.g., lethargy, confusion, seizures). It is important to exclude stroke, as treatment strategies differ. SNP is used widely in the treatment of hypertensive encephalopathy; it may increase ICP and should be used with caution. Nicardipine and labetalol are effective alternatives with favorable cerebral hemodynamic profiles.

Malignant HTN is characterized by neuroretinopathy: cotton wool spots, flame hemorrhages, and papilledema. Encephalopathy and other evidence of end-organ dysfunction might not be present, although renal disease is common. Preferred drugs are SNP and labetalol, although fenoldopam has been used successfully.

Appropriate BP management following acute ischemic stroke remains controversial. Elevated BP often is a protective physiologic response to maintain cerebral perfusion. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends initiating IV antihypertensive therapy for thrombolysis candidates when SBP >185 or DBP >110 mm Hg. For those who are not thrombolysis candidates, the recommended threshold for initiating IV antihypertensives is SBP >220 or DBP >120 mm Hg.7 The goal is to lower the BP by 15% to 25% within the first 24 hours. These goals are less aggressive than in patients with hypertensive encephalopathy without stroke.

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage causes a rise in ICP with reflex systemic hypertension. Although a correlation between HTN and hematoma expansion exists, there is no evidence that shows lowering BP is protective. Two clinical trials are evaluating the effects of BP reduction to specified target levels.8 Pending those results, the AHA recommends BP reduction for patients with SBP >200 or MAP >150 mm Hg, or for patients with SBP >180 or MAP >130 mm Hg and evidence of elevated ICP.7 In both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, nicardipine and labetalol are appropriate first-line agents.

Most sympathetic crises are related to the recreational use of sympathomimetic drugs, pheochromocytoma, abrupt antihypertensive withdrawal, or concurrent ingestion of monoamine-oxidase inhibitors and tyramine-containing foods. Selective beta-blockers can increase BP and worsen HTN through unopposed alpha effects.

Although labetalol traditionally has been considered the ideal agent—due to its alpha and beta antagonism—studies have failed to support its use in this clinical setting.9 Phentolamine, nicardipine, and fenoldopam are reasonable selections.

Hypertension is common in the early postoperative period following cardiothoracic, vascular, head and neck, and neurosurgical procedures. No consensus exists regarding the treatment of noncardiac surgery patients, but treatment is recommended for BP >140/90 or MAP >105 mmHg in cardiac surgery patients. Nicardipine, clevidipine, and esmolol are proven agents. All three have been shown more effective than SNP in maintaining target BP, and each is associated with less BP variability.10

In patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension, initial therapy for preeclampsia includes magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis and BP control until delivery of the fetus can be safely undertaken. The FDA does not recommend any specific antihypertensive agents; however, ACE inhibitors and SNP are contraindicated. Although hydralazine is used extensively in this setting, a meta-analysis showed increased risk of maternal hypotension, Cesarean section, placental abruptions, and low Apgar scores.11 Labetalol and nicardipine appear to be safe and effective in pregnant hypertensive patients.

Back to the Case

This case represents a classic presentation of malignant hypertension with hypertensive encephalopathy, which is reversible with timely and appropriate management. The patient’s MAP is approximately 165 mmHg, well above the upper threshold of cerebral vascular autoregulation in most patients with chronic hypertension. A brain MRI should be obtained to definitively rule out stroke, as management goals would be considerably different.

If the scan is negative, treatment should be initiated immediately with a goal of reducing the MAP by no more than 25% within the first hour. Nicardipine or labetalol would be appropriate therapeutic choices, administered in an ICU with close hemodynamic monitoring.

Given the patient’s end-stage renal disease and evidence of intracranial hypertension, SNP would be a suboptimal choice. Over hours two through six, BP could be lowered gradually to 160/100, then to his baseline BP over the ensuing 24 to 48 hours, monitoring closely for signs of neurologic deterioration. Once BP is stable and there is no evidence of worsening end-organ damage, he can be safely transitioned to oral agents.

Bottom Line

The therapeutic goal in hypertensive emergencies is to immediately and safely lower BP to halt end-organ damage. Drug selection should be individualized. TH

Dr. Shanahan is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Denver VA Medical Center. Dr. Linas is professor of medicine in the division of renal diseases and hypertension at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. Dr. Anderson is associate professor and chief of the hospital medicine section at the Denver VA Medical Center.

References

- Lenfant C, Chobanian AV, Jones DW, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7): resetting the hypertension sails. Hypertension. 2003;41(6):1178-1179.

- Ault MJ, Ellrodt AG. Pathophysiological events leading to the end-organ effects of acute hypertension. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3(6 Suppl):10-15.

- Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):411-417.

- Neutel JM, Smith DH, Wallin D, et al. A comparison of intravenous nicardipine and sodium nitroprusside in the immediate treatment of severe hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7(7 Pt 1):623-628.

- Shusterman NH, Elliott WJ, White WB. Fenoldopam, but not nitroprusside, improves renal function in severely hypertensive patients with impaired renal function. Am J Med. 1993;95(2):161-168.

- Khan IA, Nair CK. Clinical, diagnostic, and management perspectives of aortic dissection. Chest. 2002;122(1):311-328.

- Adams HP Jr., del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation. 2007;115(20):e478-534.

- Qureshi AI. Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH): rationale and design. Neurocrit Care. 2007;6(1):56-66.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131(6):1949-1962.

- Aronson S, Dyke CM, Stierer KA, et al. The ECLIPSE trials: comparative studies of clevidipine to nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, and nicardipine for acute hypertension treatment in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(4):1110-1121.

- Magee LA, Cham C, Waterman EJ, Ohlsson A, von Dadelszen P. Hydralazine for treatment of severe hypertension in pregnancy: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7421):955-960.

- Aggarwal M, Khan IA. Hypertensive crisis: hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. Cardiol Clin. 2006; 24(1):135-146.

- Rhoney D, Peacock WF. Intravenous therapy for hypertensive emergencies, part 1. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(15):1343-1352.

- Rhoney D, Peacock WF. Intravenous therapy for hypertensive emergencies, part 2. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(16):1448-1457.

- Varon J. Treatment of acute severe hypertension: current and newer agents. Drugs. 2008;68(3):283-297.

Case

A 57-year-old male with hypertension and end-stage renal disease is brought into the ED by his family for evaluation of headache, nausea, blurry vision, and confusion. Blood pressure is 235/130 mmHg. He is somnolent but arousable and oriented only to person; the remainder of his neurologic exam is nonfocal. A fundoscopic exam shows retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and papilledema. How should this patient be managed?

Overview

Hypertension (HTN) is a medical problem that affects an estimated 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. and more than 1 billion people worldwide. The Joint National Committee (JNC) 7 Report defines hypertensive emergency as severe hypertension with evidence of impending or progressive end-organ dysfunction.1 Systolic blood pressure (SBP) in these settings often is >180 mm Hg with diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >120 mm Hg. The JNC 7 Report defines hypertensive urgency as severe HTN without acute end-organ dysfunction. Whereas hypertensive urgencies can be treated with oral antihypertensive agents with close outpatient follow-up, hypertensive emergencies require immediate BP reduction to halt the progression of end-organ damage.

Severe HTN causes shear stress and endothelial injury, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade, fibrinoid necrosis, and tissue ischemia.2 Due to adaptive vascular changes, pre-existing hypertension lowers the probability of a hypertensive emergency developing at a particular BP. The rate of BP rise, rather than the absolute level, determines most end-organ damage.3 In previously normotensive patients, end-organ damage can occur at BPs >160/100 mm Hg; however, organ dysfunction is uncommon in chronically hypertensive individuals, unless BP >220/120 mm Hg.

Clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergency depend on the target organs involved (see Figure 1, right). When a patient presents with severe hypertension, a focused evaluation should attempt to identify the presence of end-organ damage. If present, these patients should be admitted to an ICU for close monitoring, and administration of parenteral antihypertensive agents should be started. (Online Exclusive: View a chart of “Parenteral Antihypertensive Agents Used in Hypertensive Emergencies”)

Review of the Data

General principles: The initial therapeutic goal in most hypertensive emergencies is to reduce the mean arterial pressure (MAP) by no more than 25% within the first hour. Precipitous or excessive decreases in BP might worsen renal, cerebral, or coronary ischemia. Due to pressure natriuresis, patients with primary malignant hypertension might be volume-depleted. Restoration of intravascular volume with intravenous (IV) saline can prevent precipitous falls in BP when antihypertensive agents are started.

After the patient stabilizes, the BP can be lowered about 10% per hour to 160/100-110 mm Hg. A gradual reduction to the patient’s baseline BP is targeted over the ensuing 24 to 48 hours. Once there is stable BP control and end-organ damage has ceased, patients can be transitioned to oral therapy.

No large clinical trials have investigated optimal drug therapy in patients with hypertensive emergencies. The choice of pharmacologic agent should be individualized based on drug properties, patient comorbidities, and the end-organ(s) involved.

Selected pharmacologic agents: Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is a short-acting, potent arterial and venous dilator that has been used extensively in the treatment of hypertensive emergencies. Despite its familiarity, there are several important limitations to its use. SNP can increase intracranial pressure (ICP), worsen myocardial ischemia through coronary steal, and is associated with cyanide and/or thiocyanate toxicity. Although used broadly across many types of hypertensive emergencies, SNP should be considered a first-line agent in acute left ventricular (LV) failure and, when combined with beta-blockers, in acute aortic dissection.

Labetalol is an alpha-1 and nonselective beta-blocker that reduces systemic vascular resistance while preserving cerebral, renal, and coronary blood flow. It is considered a first-line agent in most hypertensive emergencies, with the exception of acute LV failure.

Esmolol is a short-acting, selective beta-blocker that decreases heart rate, myocardial contractility, and cardiac output.

Nicardipine is a second-generation dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker. Although it has a longer duration of action, excess hypotension has not been seen in clinical trials comparing it with SNP.4 Nicardipine is used safely in such hypertensive emergencies as hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral vascular accidents, and postoperatively.

Fenoldopam creates vasodilation by acting on peripheral dopamine type 1 receptors. It improves creatinine clearance and urine output, and is most useful in acute kidney injury.5 It is a well-tolerated and highly effective agent for use in most hypertensive crises, although is expensive and has limited hard outcome data.

Nitroglycerin is a potent venodilator that is used as an adjunct to other anti-hypertensives in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes and acute pulmonary edema.

Immediate-release nifedipine and clonidine are not recommended; they are long-acting and poorly titratable, with unpredictable hypotensive effects.

Hydralazine may be used in LV failure and in pregnancy.

Specific emergencies: Aortic dissection is the most rapidly fatal complication of severe HTN. Untreated, approximately 80% of patients with acute type-A dissections die within two weeks.6 In this specific setting, SBP should be decreased as rapidly as possible to <110 mm Hg in order to halt propagation of the dissection prior to surgery. Therapy should aim to reduce the shear stress on the aortic wall by decreasing both BP and heart rate. This can be accomplished with a combination of esmolol and SNP. Nicardipine and fenoldopam are effective alternatives to SNP. Labetalol is a good single-agent option, provided adequate heart rate suppression is achieved.

LV failure and acute pulmonary edema are associated with high systemic vascular resistance and activation of the Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone (RAAS) system. First-line therapy should consist of arterial vasodilators (e.g., SNP, nicardipine, fenoldopam) in combination with a loop diuretic. Nitroglycerin can be used as an adjunct to reduce LV preload.

In hypertensive encephalopathy, blood pressure exceeds the cerebral autoregulatory threshold, leading to breakthrough vasodilation and the development of cerebral edema. Characteristic symptoms include the insidious onset of headache, nausea, vomiting, and nonlocalizing neurologic signs (e.g., lethargy, confusion, seizures). It is important to exclude stroke, as treatment strategies differ. SNP is used widely in the treatment of hypertensive encephalopathy; it may increase ICP and should be used with caution. Nicardipine and labetalol are effective alternatives with favorable cerebral hemodynamic profiles.

Malignant HTN is characterized by neuroretinopathy: cotton wool spots, flame hemorrhages, and papilledema. Encephalopathy and other evidence of end-organ dysfunction might not be present, although renal disease is common. Preferred drugs are SNP and labetalol, although fenoldopam has been used successfully.

Appropriate BP management following acute ischemic stroke remains controversial. Elevated BP often is a protective physiologic response to maintain cerebral perfusion. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends initiating IV antihypertensive therapy for thrombolysis candidates when SBP >185 or DBP >110 mm Hg. For those who are not thrombolysis candidates, the recommended threshold for initiating IV antihypertensives is SBP >220 or DBP >120 mm Hg.7 The goal is to lower the BP by 15% to 25% within the first 24 hours. These goals are less aggressive than in patients with hypertensive encephalopathy without stroke.

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage causes a rise in ICP with reflex systemic hypertension. Although a correlation between HTN and hematoma expansion exists, there is no evidence that shows lowering BP is protective. Two clinical trials are evaluating the effects of BP reduction to specified target levels.8 Pending those results, the AHA recommends BP reduction for patients with SBP >200 or MAP >150 mm Hg, or for patients with SBP >180 or MAP >130 mm Hg and evidence of elevated ICP.7 In both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, nicardipine and labetalol are appropriate first-line agents.

Most sympathetic crises are related to the recreational use of sympathomimetic drugs, pheochromocytoma, abrupt antihypertensive withdrawal, or concurrent ingestion of monoamine-oxidase inhibitors and tyramine-containing foods. Selective beta-blockers can increase BP and worsen HTN through unopposed alpha effects.

Although labetalol traditionally has been considered the ideal agent—due to its alpha and beta antagonism—studies have failed to support its use in this clinical setting.9 Phentolamine, nicardipine, and fenoldopam are reasonable selections.

Hypertension is common in the early postoperative period following cardiothoracic, vascular, head and neck, and neurosurgical procedures. No consensus exists regarding the treatment of noncardiac surgery patients, but treatment is recommended for BP >140/90 or MAP >105 mmHg in cardiac surgery patients. Nicardipine, clevidipine, and esmolol are proven agents. All three have been shown more effective than SNP in maintaining target BP, and each is associated with less BP variability.10

In patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension, initial therapy for preeclampsia includes magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis and BP control until delivery of the fetus can be safely undertaken. The FDA does not recommend any specific antihypertensive agents; however, ACE inhibitors and SNP are contraindicated. Although hydralazine is used extensively in this setting, a meta-analysis showed increased risk of maternal hypotension, Cesarean section, placental abruptions, and low Apgar scores.11 Labetalol and nicardipine appear to be safe and effective in pregnant hypertensive patients.

Back to the Case

This case represents a classic presentation of malignant hypertension with hypertensive encephalopathy, which is reversible with timely and appropriate management. The patient’s MAP is approximately 165 mmHg, well above the upper threshold of cerebral vascular autoregulation in most patients with chronic hypertension. A brain MRI should be obtained to definitively rule out stroke, as management goals would be considerably different.

If the scan is negative, treatment should be initiated immediately with a goal of reducing the MAP by no more than 25% within the first hour. Nicardipine or labetalol would be appropriate therapeutic choices, administered in an ICU with close hemodynamic monitoring.

Given the patient’s end-stage renal disease and evidence of intracranial hypertension, SNP would be a suboptimal choice. Over hours two through six, BP could be lowered gradually to 160/100, then to his baseline BP over the ensuing 24 to 48 hours, monitoring closely for signs of neurologic deterioration. Once BP is stable and there is no evidence of worsening end-organ damage, he can be safely transitioned to oral agents.

Bottom Line

The therapeutic goal in hypertensive emergencies is to immediately and safely lower BP to halt end-organ damage. Drug selection should be individualized. TH

Dr. Shanahan is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Denver VA Medical Center. Dr. Linas is professor of medicine in the division of renal diseases and hypertension at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. Dr. Anderson is associate professor and chief of the hospital medicine section at the Denver VA Medical Center.

References

- Lenfant C, Chobanian AV, Jones DW, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7): resetting the hypertension sails. Hypertension. 2003;41(6):1178-1179.

- Ault MJ, Ellrodt AG. Pathophysiological events leading to the end-organ effects of acute hypertension. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3(6 Suppl):10-15.

- Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):411-417.

- Neutel JM, Smith DH, Wallin D, et al. A comparison of intravenous nicardipine and sodium nitroprusside in the immediate treatment of severe hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7(7 Pt 1):623-628.

- Shusterman NH, Elliott WJ, White WB. Fenoldopam, but not nitroprusside, improves renal function in severely hypertensive patients with impaired renal function. Am J Med. 1993;95(2):161-168.

- Khan IA, Nair CK. Clinical, diagnostic, and management perspectives of aortic dissection. Chest. 2002;122(1):311-328.