User login

Clinical Challenges - July 2016:Angiosarcoma of the colon with multiple liver metastases

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

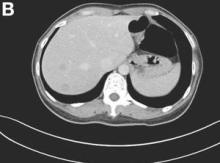

The colonoscopy disclosed an erythematous, ulcerated tumor with spontaneous bleeding in the ascending colon (Figure A). Noncontrast abdominal CT showed multiple hypoattenuating lesions in the liver. These lesions had central enhancement in the early arterial phase and progressive enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure B).

Angiosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor arising from vascular endothelium. These tumors usually develop in skin and in the soft tissue of the head and neck region.1 Gastrointestinal angiosarcomas are rare with fewer than 20 cases reported in the literature.1,2 Patients with colonic angiosarcoma usually present with abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or a palpable abdominal mass.1,2 On colonoscopy, the tumor has been described as a submucosal tumor1,2or a hemorrhagic mass with spontaneous bleeding3, as in this case.

1. Lo, T.H., Tsai, M.S., Chen, T.A. Angiosarcoma of sigmoid colon with intraperitoneal bleeding: case report and literature review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e91-3.

2. El Chaar, M., McQuay, N. Jr. Sigmoid colon angiosarcoma with intraperitoneal bleeding and early metastasis. J Surg Educ. 2007;64: 54-6.

3. Cammarota, G., Schinzari, G., Larocca, L.M. et al. Duodenal metastasis from a primary angiosarcoma of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:330.

The diagnosis

The colonoscopy disclosed an erythematous, ulcerated tumor with spontaneous bleeding in the ascending colon (Figure A). Noncontrast abdominal CT showed multiple hypoattenuating lesions in the liver. These lesions had central enhancement in the early arterial phase and progressive enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure B).

Angiosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor arising from vascular endothelium. These tumors usually develop in skin and in the soft tissue of the head and neck region.1 Gastrointestinal angiosarcomas are rare with fewer than 20 cases reported in the literature.1,2 Patients with colonic angiosarcoma usually present with abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or a palpable abdominal mass.1,2 On colonoscopy, the tumor has been described as a submucosal tumor1,2or a hemorrhagic mass with spontaneous bleeding3, as in this case.

1. Lo, T.H., Tsai, M.S., Chen, T.A. Angiosarcoma of sigmoid colon with intraperitoneal bleeding: case report and literature review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e91-3.

2. El Chaar, M., McQuay, N. Jr. Sigmoid colon angiosarcoma with intraperitoneal bleeding and early metastasis. J Surg Educ. 2007;64: 54-6.

3. Cammarota, G., Schinzari, G., Larocca, L.M. et al. Duodenal metastasis from a primary angiosarcoma of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:330.

The diagnosis

The colonoscopy disclosed an erythematous, ulcerated tumor with spontaneous bleeding in the ascending colon (Figure A). Noncontrast abdominal CT showed multiple hypoattenuating lesions in the liver. These lesions had central enhancement in the early arterial phase and progressive enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure B).

Angiosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor arising from vascular endothelium. These tumors usually develop in skin and in the soft tissue of the head and neck region.1 Gastrointestinal angiosarcomas are rare with fewer than 20 cases reported in the literature.1,2 Patients with colonic angiosarcoma usually present with abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or a palpable abdominal mass.1,2 On colonoscopy, the tumor has been described as a submucosal tumor1,2or a hemorrhagic mass with spontaneous bleeding3, as in this case.

1. Lo, T.H., Tsai, M.S., Chen, T.A. Angiosarcoma of sigmoid colon with intraperitoneal bleeding: case report and literature review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e91-3.

2. El Chaar, M., McQuay, N. Jr. Sigmoid colon angiosarcoma with intraperitoneal bleeding and early metastasis. J Surg Educ. 2007;64: 54-6.

3. Cammarota, G., Schinzari, G., Larocca, L.M. et al. Duodenal metastasis from a primary angiosarcoma of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:330.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Dr. Maw-Soan Soon, Dr. Chih-Jung Chen, and Dr. Hsu-Heng Yen. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012:143:1155, 1400).

She denied weight loss or change in bowel habits.

A stool fecal occult test was positive and colonoscopy was performed (Figure A).

Clinical Challenges - June 2016: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

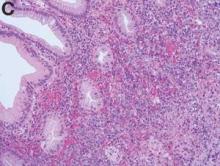

The radiograph (Figure B) and CT scan (Figure C) of the neck revealed severe calcification of soft tissue along the anterior portion of cervical spine starting from C2 to T1. The calcification is pressing on the esophagus and also displaces the trachea forward.

These findings are consistent with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Initially, the patient was treated with partial liquid diet and nutritional supplement. Subsequently, the patient underwent orthopedic consultation for surgical consideration.

DISH is a noninflammatory ossification and calcification of ligaments and tendons anterior to the spine. Even though this condition was first described by Forestier et al. in 1950,1 the etiology and pathogenesis of DISH remain unknown. Many risk factors have been postulated to be associated with DISH, such as mechanical factors, diet, and drugs. DISH is more prevalent among the elderly, especially, males; however, it is a rare cause of dysphagia.2 The clinical manifestation varies depending on the location of calcification. There have been case reports of DISH causing dysphagia, difficult airway management, and spinal cord root compression.3

For esophageal involvement, the severity of symptoms is correlated with degree of compression. Initially, DISH may cause only an isolated globus sensation without any significant dysphagia. However, as the compression progresses, it can cause significant progressive dysphagia that mimics the presentation of esophageal cancer. Thus, the effort to rule out esophageal cancer or other structural diseases is needed before the diagnosis of DISH can be established, such as an upper endoscopy or CT of the neck.

Because DISH can resemble benign degenerative osteophytes on a plain neck radiograph, it is sometimes overlooked by physicians. DISH is an uncommon condition; it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia, especially in the elderly population.References

1. Forestier, J., Rotes-Querol, J. Senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1950;9:321-30.

2. Schlapbach, P., Beyeler, C., Gerber, N.J., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the spine: a cause of back pain? (A controlled study). Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28:299-303.

3. Verlaan, J.J., Boswijk, P.F., de Ru, J.A., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the cervical spine: an underestimated cause of dysphagia and airway obstruction. Spine J. 2011;11:1058-67.

The diagnosis

The radiograph (Figure B) and CT scan (Figure C) of the neck revealed severe calcification of soft tissue along the anterior portion of cervical spine starting from C2 to T1. The calcification is pressing on the esophagus and also displaces the trachea forward.

These findings are consistent with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Initially, the patient was treated with partial liquid diet and nutritional supplement. Subsequently, the patient underwent orthopedic consultation for surgical consideration.

DISH is a noninflammatory ossification and calcification of ligaments and tendons anterior to the spine. Even though this condition was first described by Forestier et al. in 1950,1 the etiology and pathogenesis of DISH remain unknown. Many risk factors have been postulated to be associated with DISH, such as mechanical factors, diet, and drugs. DISH is more prevalent among the elderly, especially, males; however, it is a rare cause of dysphagia.2 The clinical manifestation varies depending on the location of calcification. There have been case reports of DISH causing dysphagia, difficult airway management, and spinal cord root compression.3

For esophageal involvement, the severity of symptoms is correlated with degree of compression. Initially, DISH may cause only an isolated globus sensation without any significant dysphagia. However, as the compression progresses, it can cause significant progressive dysphagia that mimics the presentation of esophageal cancer. Thus, the effort to rule out esophageal cancer or other structural diseases is needed before the diagnosis of DISH can be established, such as an upper endoscopy or CT of the neck.

Because DISH can resemble benign degenerative osteophytes on a plain neck radiograph, it is sometimes overlooked by physicians. DISH is an uncommon condition; it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia, especially in the elderly population.References

1. Forestier, J., Rotes-Querol, J. Senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1950;9:321-30.

2. Schlapbach, P., Beyeler, C., Gerber, N.J., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the spine: a cause of back pain? (A controlled study). Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28:299-303.

3. Verlaan, J.J., Boswijk, P.F., de Ru, J.A., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the cervical spine: an underestimated cause of dysphagia and airway obstruction. Spine J. 2011;11:1058-67.

The diagnosis

The radiograph (Figure B) and CT scan (Figure C) of the neck revealed severe calcification of soft tissue along the anterior portion of cervical spine starting from C2 to T1. The calcification is pressing on the esophagus and also displaces the trachea forward.

These findings are consistent with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Initially, the patient was treated with partial liquid diet and nutritional supplement. Subsequently, the patient underwent orthopedic consultation for surgical consideration.

DISH is a noninflammatory ossification and calcification of ligaments and tendons anterior to the spine. Even though this condition was first described by Forestier et al. in 1950,1 the etiology and pathogenesis of DISH remain unknown. Many risk factors have been postulated to be associated with DISH, such as mechanical factors, diet, and drugs. DISH is more prevalent among the elderly, especially, males; however, it is a rare cause of dysphagia.2 The clinical manifestation varies depending on the location of calcification. There have been case reports of DISH causing dysphagia, difficult airway management, and spinal cord root compression.3

For esophageal involvement, the severity of symptoms is correlated with degree of compression. Initially, DISH may cause only an isolated globus sensation without any significant dysphagia. However, as the compression progresses, it can cause significant progressive dysphagia that mimics the presentation of esophageal cancer. Thus, the effort to rule out esophageal cancer or other structural diseases is needed before the diagnosis of DISH can be established, such as an upper endoscopy or CT of the neck.

Because DISH can resemble benign degenerative osteophytes on a plain neck radiograph, it is sometimes overlooked by physicians. DISH is an uncommon condition; it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia, especially in the elderly population.References

1. Forestier, J., Rotes-Querol, J. Senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1950;9:321-30.

2. Schlapbach, P., Beyeler, C., Gerber, N.J., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the spine: a cause of back pain? (A controlled study). Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28:299-303.

3. Verlaan, J.J., Boswijk, P.F., de Ru, J.A., et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the cervical spine: an underestimated cause of dysphagia and airway obstruction. Spine J. 2011;11:1058-67.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

Upon arrival, his vital signs were stable. Physical examination was unremarkable. No cervical lymphadenopathy or masses were appreciated in his neck. Hemoglobin, platelets, and white blood cell count were within normal reference ranges. An esophagogram was initially performed, illustrating mildly thickened folds of distal esophagus with no obstruction or ulcer (Figure A).

Upper endoscopy was subsequently performed, revealing normal esophageal mucosa without any strictures. An ENT specialist was consulted because of the concern of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Laryngoscope and video swallowing evaluations were performed; the results were normal. Ultimately, a neck radiograph and computed tomography (CT) of the neck were performed (Figures B and C).

Clinical Challenges - May 2016: Pancreaticobiliary maljunction with bifid pancreatic ducts presenting as recurrent pancreatitis and concurrent gallbladder adenocarcinoma

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Figure A shows marked intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation and an irregular enhancing mass along the lateral wall of the gallbladder (long arrow). Figure B shows an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction, with the common bile duct inserting into a distal pancreatic duct to form a cystically dilated common channel (arrowhead), as well as a bifid main pancreatic duct (long arrow). Figure C shows a bifid pancreatic duct and no evidence of a pancreatic mass. Other endoscopic ultrasound images visualized an irregular gallbladder mass. Figure D shows an irregular mass in the gallbladder wall, with final pathology revealing an invasive, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder (long arrow) with negative margins and no evidence of lymph node involvement (T1N0Mx). The final diagnosis was pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) with bifid pancreatic ducts presenting as recurrent pancreatitis and concurrent gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

It is well established that PBM, an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system, is frequently associated with carcinomas of the biliary tract. First described in 1916 by Kozumi and Kodama, PBM is a rare congenital malformation most prevalent in Asia that is defined as an anomalous junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts located outside of the duodenal wall.1PBM often manifests clinically as intermittent abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and/or acute pancreatitis, although patients may be asymptomatic. The most concerning problem, however, is the close relationship of biliary tract carcinogenesis to PBM, with gallbladder carcinoma and bile duct cancers arising in 14.8% and 4.9% of patients with PBM, respectively.2 The anomalous junction is thought to preclude normal sphincter of Oddi function, thus facilitating the reciprocal reflux of bile and pancreatic juice and ultimately leading to biliary carcinogenesis. Tumor markers, such as CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen, may be of some diagnostic value in PBM and biliary tract neoplasms, although they lack sensitivity and specificity because of significant overlap with benign disease, such as pancreatitis. This particular case had the added novelty of a bifid pancreatic duct. The clinical significance of a bifid pancreatic duct is unclear, and no relationship has been demonstrated between this ductal anomaly and pancreaticobiliary disease. In this case, a pancreaticoduodenectomy with en bloc resection of the gallbladder was performed to resect the gallbladder mass with clear margins and eliminate the risk for further biliary tract carcinogenesis while simultaneously excising the anomalous junction thought to be causing the recurrent pancreatitis.

References

1. Todani T., Arima E., Eto T., et al. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219-21.

2. Funabiki T., Matsubara T., Miyakawa S., et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;39:149-69.

The diagnosis

Figure A shows marked intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation and an irregular enhancing mass along the lateral wall of the gallbladder (long arrow). Figure B shows an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction, with the common bile duct inserting into a distal pancreatic duct to form a cystically dilated common channel (arrowhead), as well as a bifid main pancreatic duct (long arrow). Figure C shows a bifid pancreatic duct and no evidence of a pancreatic mass. Other endoscopic ultrasound images visualized an irregular gallbladder mass. Figure D shows an irregular mass in the gallbladder wall, with final pathology revealing an invasive, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder (long arrow) with negative margins and no evidence of lymph node involvement (T1N0Mx). The final diagnosis was pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) with bifid pancreatic ducts presenting as recurrent pancreatitis and concurrent gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

It is well established that PBM, an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system, is frequently associated with carcinomas of the biliary tract. First described in 1916 by Kozumi and Kodama, PBM is a rare congenital malformation most prevalent in Asia that is defined as an anomalous junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts located outside of the duodenal wall.1PBM often manifests clinically as intermittent abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and/or acute pancreatitis, although patients may be asymptomatic. The most concerning problem, however, is the close relationship of biliary tract carcinogenesis to PBM, with gallbladder carcinoma and bile duct cancers arising in 14.8% and 4.9% of patients with PBM, respectively.2 The anomalous junction is thought to preclude normal sphincter of Oddi function, thus facilitating the reciprocal reflux of bile and pancreatic juice and ultimately leading to biliary carcinogenesis. Tumor markers, such as CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen, may be of some diagnostic value in PBM and biliary tract neoplasms, although they lack sensitivity and specificity because of significant overlap with benign disease, such as pancreatitis. This particular case had the added novelty of a bifid pancreatic duct. The clinical significance of a bifid pancreatic duct is unclear, and no relationship has been demonstrated between this ductal anomaly and pancreaticobiliary disease. In this case, a pancreaticoduodenectomy with en bloc resection of the gallbladder was performed to resect the gallbladder mass with clear margins and eliminate the risk for further biliary tract carcinogenesis while simultaneously excising the anomalous junction thought to be causing the recurrent pancreatitis.

References

1. Todani T., Arima E., Eto T., et al. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219-21.

2. Funabiki T., Matsubara T., Miyakawa S., et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;39:149-69.

The diagnosis

Figure A shows marked intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation and an irregular enhancing mass along the lateral wall of the gallbladder (long arrow). Figure B shows an abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction, with the common bile duct inserting into a distal pancreatic duct to form a cystically dilated common channel (arrowhead), as well as a bifid main pancreatic duct (long arrow). Figure C shows a bifid pancreatic duct and no evidence of a pancreatic mass. Other endoscopic ultrasound images visualized an irregular gallbladder mass. Figure D shows an irregular mass in the gallbladder wall, with final pathology revealing an invasive, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder (long arrow) with negative margins and no evidence of lymph node involvement (T1N0Mx). The final diagnosis was pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) with bifid pancreatic ducts presenting as recurrent pancreatitis and concurrent gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

It is well established that PBM, an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system, is frequently associated with carcinomas of the biliary tract. First described in 1916 by Kozumi and Kodama, PBM is a rare congenital malformation most prevalent in Asia that is defined as an anomalous junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts located outside of the duodenal wall.1PBM often manifests clinically as intermittent abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and/or acute pancreatitis, although patients may be asymptomatic. The most concerning problem, however, is the close relationship of biliary tract carcinogenesis to PBM, with gallbladder carcinoma and bile duct cancers arising in 14.8% and 4.9% of patients with PBM, respectively.2 The anomalous junction is thought to preclude normal sphincter of Oddi function, thus facilitating the reciprocal reflux of bile and pancreatic juice and ultimately leading to biliary carcinogenesis. Tumor markers, such as CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen, may be of some diagnostic value in PBM and biliary tract neoplasms, although they lack sensitivity and specificity because of significant overlap with benign disease, such as pancreatitis. This particular case had the added novelty of a bifid pancreatic duct. The clinical significance of a bifid pancreatic duct is unclear, and no relationship has been demonstrated between this ductal anomaly and pancreaticobiliary disease. In this case, a pancreaticoduodenectomy with en bloc resection of the gallbladder was performed to resect the gallbladder mass with clear margins and eliminate the risk for further biliary tract carcinogenesis while simultaneously excising the anomalous junction thought to be causing the recurrent pancreatitis.

References

1. Todani T., Arima E., Eto T., et al. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219-21.

2. Funabiki T., Matsubara T., Miyakawa S., et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;39:149-69.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Dr. Katherine Albutt, Dr. Laurence Bailen, and Dr. Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143:896, 1121-2).

A 63-year-old African American woman with a history of recurrent pancreatitis was admitted with severe right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back. Her medical history was notable for three prior episodes of pancreatitis that required hospitalization in 2000, 2006, and 2007.

On the day of admission, physical examination revealed a soft abdomen that was tender to palpation in the right upper quadrant with a positive Murphy’s sign. Laboratory data were notable for an amylase level of 1,203 U/L and a lipase level of 2,091 U/L in the setting of normal liver function tests (LFTs) and a normal leukocyte count. The cancer antigen (CA) 19-9 level at this time was 299 U/mL.

The patient then underwent abdominal sonography and computed tomography (Figure A). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was also performed (Figure B). Because of rising LFTs, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed, and a biliary stent was placed. An endoscopic ultrasound was performed at the time of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (Figure C).

Once the acute pancreatitis resolved and the patient was tolerating a regular diet, she was discharged home. At this time, the level of CA 19-9 was 35 U/mL. She was subsequently taken to the operating room for a planned pancreaticoduodenectomy, cholecystectomy, and dissection of periportal lymph nodes. The Whipple specimen was removed en bloc with the gallbladder (Figure D).

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged home on postoperative day 7. Postoperative laboratory values were notable for a CA 19-9 of 23 U/mL and carcinoembryonic antigen of 3.3 ng/mL. What is the diagnosis?