User login

A Practical Guide for Developing a Relationship with the Pharmaceutical, Biotech, and Device Industries

The primary goal of the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry is to develop medications and medical devices for the treatment of patients, while earning financial gain for investors. An important component of achieving this goal is the role physicians play in the drug and medical device development process. In particular, a physician’s role is to combine their clinical expertise with their knowledge of industry products to better diagnose and treat the ailments of their patients. Thus, medicine and industry have a dependent relationship. In recent times this relationship has been fraught with turmoil as the public, scientific community, and federal government have discovered real and perceived conflicts of interest.

For example, there has been public outrage in the past with reports of doctors receiving gifts, money, and lavish trips in return for prescribing medications or using certain medical devices. Because of this, Congress passed the Sunshine Act, deeming it necessary to report all physician and industry engagements that have any perceived financial value. The passage of this act was in addition to local policies set forth by academic institutions, hospitals, and private practices.

How Do I Get Started?

After checking with your institution, hospital or private practice administrator, the first step is to reach out to a local representative (“rep”) of a pharmaceutical or biotech company in which you are interested. You can accomplish this via the website of the company or by visiting the booth at major gastrointestinal conferences such as Digestive Disease Week (DDW®).

Pharma and device reps are quite knowledgeable about the latest clinical studies regarding their products, disease states, and various competing products in the market. In addition to being a source of valuable medical knowledge and disease-specific practice guidelines, they also can connect you with their medical science liaison (MSL). MSLs often have a background in pharmacy and/or research. Thus, they can provide insights into mechanisms of disease treatments and go beyond discussion of the product label, which pharmaceutical reps adhere to. They also know what therapies or diagnostic tools are in the phases of development and could be available for a clinical trial.

MSLs are also the gatekeepers for Investigator Initiated Studies (IIS). An IIS is a research project that is industry-funded and is solely designed and executed by the clinician. The application process is rigorous but awards may be easier to obtain for non-research-based clinicians who want to develop a disease-specific project that needs funding. Their grant application process can be brief, ideas may not require prior data, and turnaround time to funding may be shorter. IISs often lead to exploratory findings that may facilitate publications or lay groundwork for large-scale grants or even clinical trials. In some instances, you may be granted access to internal data and prescribing patterns, which can answer interesting clinical and research questions.

How Do I Get Started with Clinical Trials?

Being a primary investigator on a clinical trial is a big responsibility. You are responsible to the trial sponsor in addition to your patients. For young clinicians who lack experience with clinical trials, the first thing to do is to find a clinician in your department or another department, who has expertise in performing an industry-sponsored study. These individuals can be invaluable for you in terms of guiding you through the study feasibility process, study startup, and possibly being the lead or co-investigator with you. Partnering with someone with expertise in industry-sponsored clinical trials will help you gain the trust of the industry sponsor, which may be a requirement for some.

There are many additional requirements that need to be fulfilled aside from just having an appropriate and adequate patient population to pull from. You will need to have a coordinator for the study who will help you with patient care, data entry, and study- specific issues. Clinical trials require a significant amount of documentation and reporting that has to be performed within a timely manner. There is no degree prerequisite of the coordinator but it can simplify things for the clinician if they have a RN or LPN degree. Having such a degree will facilitate dual roles of patient care, lab draws, drug administration, medical charting, and other patient care matters.

In addition, you will need to have approval from either your local or central institutional review board (IRB). Also, you will have to review budget and study-specific requirements for equipment and infrastructure with your department manager. You will need to demonstrate adequate ancillary support to process, store, and ship biological specimens. In some instances, you will need a dedicated pharmacist to mix or dispense study drugs.

The process is lengthy and involved, but rewarding in terms of being involved in the drug development process. You will have opportunities to attend meetings at which you can network with other clinicians and provide the sponsor feedback on how the study is going.

How Do I Develop a Consulting Role with Industry?

It is important to check with your institution, hospital, or practice if there are any limitations in becoming a consultant for a pharmaceutical or device company. If it is allowed and will not interfere with your clinical duties, it is important to note that this role takes time to develop. It often comes about after years of experience doing research, clinical and/or basic science, with publications to support expertise. Working on an IIS is a good way to work hand-in-hand with expert industry researchers and facilitate the consulting relationship. Being a primary investigator of clinical trials with successful enrollment of patients and meeting attendance will provide you with insight into the drug development process.

What if None of This Works Out for Me?

Do not give up! Persistence, experience, and hard work are the keys to developing relationships with industry. Remember, industry has a vast network of clinicians and researchers they already work with. The overall pool of companies and experts is limited and can be difficult to break into. But it can be done. Some rely on their research experience, clinical training, and mentors to develop the necessary contacts. Others can develop the contacts via IIS applications. Industry lacks access to the physician-patient experience; this can be your greatest asset and key to your success if leveraged properly. You can consider applying for mentorship with experts in your field via AGA-sponsored events held annually at DDW® to get additional guidance.

Final Thoughts

It is important to remember that all industry relationships require time to develop. They also come at an opportunity cost of time away from your clinical practice and your family, friends and hobbies. However, these relationships also offer a way to increase your insight into new and old treatment and diagnostic paradigms. It is also a way to remain excited about your field and prevent the feeling that your day-to-day clinical practice is becoming routine.

Dr. Nitin Gupta is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Program Director for the Gastroenterology Fellowship at University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He has worked in basic science, translational and clinical research and continues projects in these areas. He has experience working with industry via roles of being a primary investigator in several clinical trials and consulting relationships.

The primary goal of the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry is to develop medications and medical devices for the treatment of patients, while earning financial gain for investors. An important component of achieving this goal is the role physicians play in the drug and medical device development process. In particular, a physician’s role is to combine their clinical expertise with their knowledge of industry products to better diagnose and treat the ailments of their patients. Thus, medicine and industry have a dependent relationship. In recent times this relationship has been fraught with turmoil as the public, scientific community, and federal government have discovered real and perceived conflicts of interest.

For example, there has been public outrage in the past with reports of doctors receiving gifts, money, and lavish trips in return for prescribing medications or using certain medical devices. Because of this, Congress passed the Sunshine Act, deeming it necessary to report all physician and industry engagements that have any perceived financial value. The passage of this act was in addition to local policies set forth by academic institutions, hospitals, and private practices.

How Do I Get Started?

After checking with your institution, hospital or private practice administrator, the first step is to reach out to a local representative (“rep”) of a pharmaceutical or biotech company in which you are interested. You can accomplish this via the website of the company or by visiting the booth at major gastrointestinal conferences such as Digestive Disease Week (DDW®).

Pharma and device reps are quite knowledgeable about the latest clinical studies regarding their products, disease states, and various competing products in the market. In addition to being a source of valuable medical knowledge and disease-specific practice guidelines, they also can connect you with their medical science liaison (MSL). MSLs often have a background in pharmacy and/or research. Thus, they can provide insights into mechanisms of disease treatments and go beyond discussion of the product label, which pharmaceutical reps adhere to. They also know what therapies or diagnostic tools are in the phases of development and could be available for a clinical trial.

MSLs are also the gatekeepers for Investigator Initiated Studies (IIS). An IIS is a research project that is industry-funded and is solely designed and executed by the clinician. The application process is rigorous but awards may be easier to obtain for non-research-based clinicians who want to develop a disease-specific project that needs funding. Their grant application process can be brief, ideas may not require prior data, and turnaround time to funding may be shorter. IISs often lead to exploratory findings that may facilitate publications or lay groundwork for large-scale grants or even clinical trials. In some instances, you may be granted access to internal data and prescribing patterns, which can answer interesting clinical and research questions.

How Do I Get Started with Clinical Trials?

Being a primary investigator on a clinical trial is a big responsibility. You are responsible to the trial sponsor in addition to your patients. For young clinicians who lack experience with clinical trials, the first thing to do is to find a clinician in your department or another department, who has expertise in performing an industry-sponsored study. These individuals can be invaluable for you in terms of guiding you through the study feasibility process, study startup, and possibly being the lead or co-investigator with you. Partnering with someone with expertise in industry-sponsored clinical trials will help you gain the trust of the industry sponsor, which may be a requirement for some.

There are many additional requirements that need to be fulfilled aside from just having an appropriate and adequate patient population to pull from. You will need to have a coordinator for the study who will help you with patient care, data entry, and study- specific issues. Clinical trials require a significant amount of documentation and reporting that has to be performed within a timely manner. There is no degree prerequisite of the coordinator but it can simplify things for the clinician if they have a RN or LPN degree. Having such a degree will facilitate dual roles of patient care, lab draws, drug administration, medical charting, and other patient care matters.

In addition, you will need to have approval from either your local or central institutional review board (IRB). Also, you will have to review budget and study-specific requirements for equipment and infrastructure with your department manager. You will need to demonstrate adequate ancillary support to process, store, and ship biological specimens. In some instances, you will need a dedicated pharmacist to mix or dispense study drugs.

The process is lengthy and involved, but rewarding in terms of being involved in the drug development process. You will have opportunities to attend meetings at which you can network with other clinicians and provide the sponsor feedback on how the study is going.

How Do I Develop a Consulting Role with Industry?

It is important to check with your institution, hospital, or practice if there are any limitations in becoming a consultant for a pharmaceutical or device company. If it is allowed and will not interfere with your clinical duties, it is important to note that this role takes time to develop. It often comes about after years of experience doing research, clinical and/or basic science, with publications to support expertise. Working on an IIS is a good way to work hand-in-hand with expert industry researchers and facilitate the consulting relationship. Being a primary investigator of clinical trials with successful enrollment of patients and meeting attendance will provide you with insight into the drug development process.

What if None of This Works Out for Me?

Do not give up! Persistence, experience, and hard work are the keys to developing relationships with industry. Remember, industry has a vast network of clinicians and researchers they already work with. The overall pool of companies and experts is limited and can be difficult to break into. But it can be done. Some rely on their research experience, clinical training, and mentors to develop the necessary contacts. Others can develop the contacts via IIS applications. Industry lacks access to the physician-patient experience; this can be your greatest asset and key to your success if leveraged properly. You can consider applying for mentorship with experts in your field via AGA-sponsored events held annually at DDW® to get additional guidance.

Final Thoughts

It is important to remember that all industry relationships require time to develop. They also come at an opportunity cost of time away from your clinical practice and your family, friends and hobbies. However, these relationships also offer a way to increase your insight into new and old treatment and diagnostic paradigms. It is also a way to remain excited about your field and prevent the feeling that your day-to-day clinical practice is becoming routine.

Dr. Nitin Gupta is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Program Director for the Gastroenterology Fellowship at University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He has worked in basic science, translational and clinical research and continues projects in these areas. He has experience working with industry via roles of being a primary investigator in several clinical trials and consulting relationships.

The primary goal of the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry is to develop medications and medical devices for the treatment of patients, while earning financial gain for investors. An important component of achieving this goal is the role physicians play in the drug and medical device development process. In particular, a physician’s role is to combine their clinical expertise with their knowledge of industry products to better diagnose and treat the ailments of their patients. Thus, medicine and industry have a dependent relationship. In recent times this relationship has been fraught with turmoil as the public, scientific community, and federal government have discovered real and perceived conflicts of interest.

For example, there has been public outrage in the past with reports of doctors receiving gifts, money, and lavish trips in return for prescribing medications or using certain medical devices. Because of this, Congress passed the Sunshine Act, deeming it necessary to report all physician and industry engagements that have any perceived financial value. The passage of this act was in addition to local policies set forth by academic institutions, hospitals, and private practices.

How Do I Get Started?

After checking with your institution, hospital or private practice administrator, the first step is to reach out to a local representative (“rep”) of a pharmaceutical or biotech company in which you are interested. You can accomplish this via the website of the company or by visiting the booth at major gastrointestinal conferences such as Digestive Disease Week (DDW®).

Pharma and device reps are quite knowledgeable about the latest clinical studies regarding their products, disease states, and various competing products in the market. In addition to being a source of valuable medical knowledge and disease-specific practice guidelines, they also can connect you with their medical science liaison (MSL). MSLs often have a background in pharmacy and/or research. Thus, they can provide insights into mechanisms of disease treatments and go beyond discussion of the product label, which pharmaceutical reps adhere to. They also know what therapies or diagnostic tools are in the phases of development and could be available for a clinical trial.

MSLs are also the gatekeepers for Investigator Initiated Studies (IIS). An IIS is a research project that is industry-funded and is solely designed and executed by the clinician. The application process is rigorous but awards may be easier to obtain for non-research-based clinicians who want to develop a disease-specific project that needs funding. Their grant application process can be brief, ideas may not require prior data, and turnaround time to funding may be shorter. IISs often lead to exploratory findings that may facilitate publications or lay groundwork for large-scale grants or even clinical trials. In some instances, you may be granted access to internal data and prescribing patterns, which can answer interesting clinical and research questions.

How Do I Get Started with Clinical Trials?

Being a primary investigator on a clinical trial is a big responsibility. You are responsible to the trial sponsor in addition to your patients. For young clinicians who lack experience with clinical trials, the first thing to do is to find a clinician in your department or another department, who has expertise in performing an industry-sponsored study. These individuals can be invaluable for you in terms of guiding you through the study feasibility process, study startup, and possibly being the lead or co-investigator with you. Partnering with someone with expertise in industry-sponsored clinical trials will help you gain the trust of the industry sponsor, which may be a requirement for some.

There are many additional requirements that need to be fulfilled aside from just having an appropriate and adequate patient population to pull from. You will need to have a coordinator for the study who will help you with patient care, data entry, and study- specific issues. Clinical trials require a significant amount of documentation and reporting that has to be performed within a timely manner. There is no degree prerequisite of the coordinator but it can simplify things for the clinician if they have a RN or LPN degree. Having such a degree will facilitate dual roles of patient care, lab draws, drug administration, medical charting, and other patient care matters.

In addition, you will need to have approval from either your local or central institutional review board (IRB). Also, you will have to review budget and study-specific requirements for equipment and infrastructure with your department manager. You will need to demonstrate adequate ancillary support to process, store, and ship biological specimens. In some instances, you will need a dedicated pharmacist to mix or dispense study drugs.

The process is lengthy and involved, but rewarding in terms of being involved in the drug development process. You will have opportunities to attend meetings at which you can network with other clinicians and provide the sponsor feedback on how the study is going.

How Do I Develop a Consulting Role with Industry?

It is important to check with your institution, hospital, or practice if there are any limitations in becoming a consultant for a pharmaceutical or device company. If it is allowed and will not interfere with your clinical duties, it is important to note that this role takes time to develop. It often comes about after years of experience doing research, clinical and/or basic science, with publications to support expertise. Working on an IIS is a good way to work hand-in-hand with expert industry researchers and facilitate the consulting relationship. Being a primary investigator of clinical trials with successful enrollment of patients and meeting attendance will provide you with insight into the drug development process.

What if None of This Works Out for Me?

Do not give up! Persistence, experience, and hard work are the keys to developing relationships with industry. Remember, industry has a vast network of clinicians and researchers they already work with. The overall pool of companies and experts is limited and can be difficult to break into. But it can be done. Some rely on their research experience, clinical training, and mentors to develop the necessary contacts. Others can develop the contacts via IIS applications. Industry lacks access to the physician-patient experience; this can be your greatest asset and key to your success if leveraged properly. You can consider applying for mentorship with experts in your field via AGA-sponsored events held annually at DDW® to get additional guidance.

Final Thoughts

It is important to remember that all industry relationships require time to develop. They also come at an opportunity cost of time away from your clinical practice and your family, friends and hobbies. However, these relationships also offer a way to increase your insight into new and old treatment and diagnostic paradigms. It is also a way to remain excited about your field and prevent the feeling that your day-to-day clinical practice is becoming routine.

Dr. Nitin Gupta is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Program Director for the Gastroenterology Fellowship at University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He has worked in basic science, translational and clinical research and continues projects in these areas. He has experience working with industry via roles of being a primary investigator in several clinical trials and consulting relationships.

Building and Maintaining a Successful Inflammatory Bowel Disease Practice

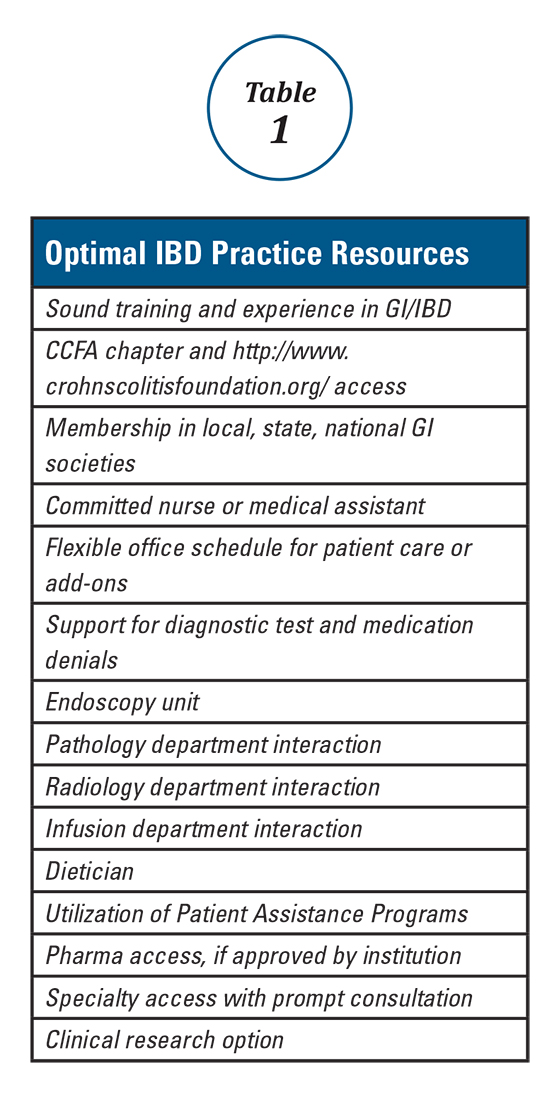

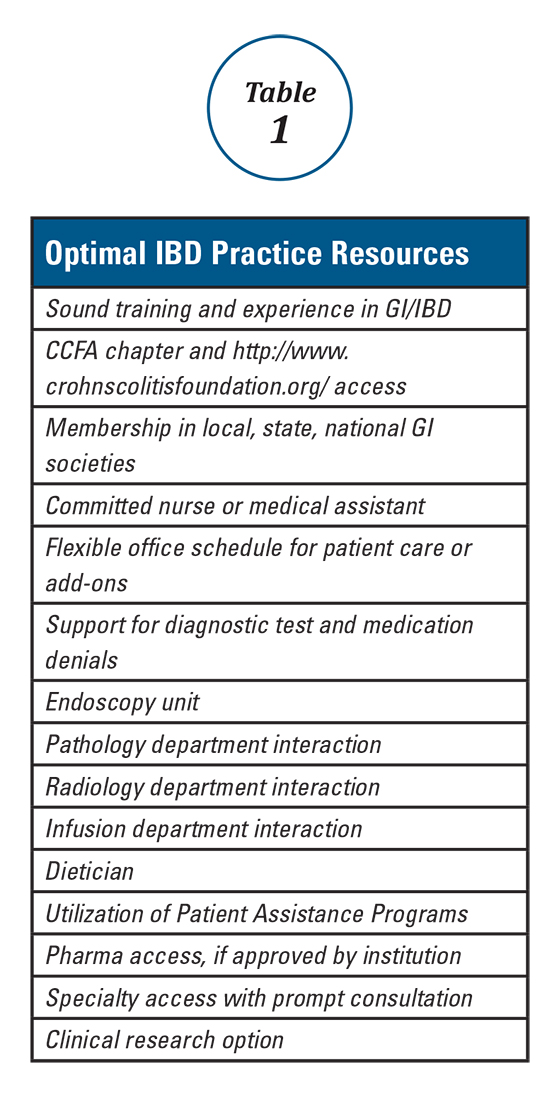

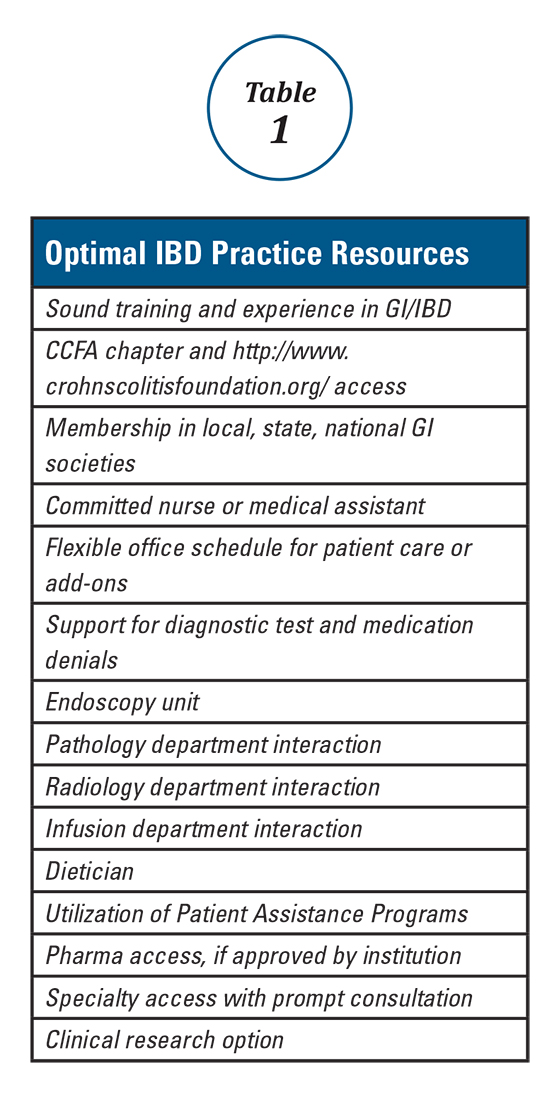

Anyone can build a successful inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) practice. To do so requires commitment and focus in the area of IBD including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. It also requires a fundamental knowledge of medicine as well as a desire to excel and learn all that one can in these areas. Given the high number of stakeholders, good interpersonal skills are vital. Establishing an IBD practice provides an opportunity to make a big difference in peoples’ lives and the age range of impact is about the broadest in all of medical practice. The more resources you have, the greater the potential impact of your care. Table 1 lists resources that are useful to provide optimal IBD patient care.

You, the gastroenterologist, is the most important resource for the patient. Medical school, residency, fellowship, and “postgraduate” training serves as the foundation for your wealth of knowledge. Maximizing your training is of value, and this can be done by being part of an academic program, keeping abreast of current literature, and attending meetings and post-graduate courses. AGA offers a variety of publications (http://www.gastro.org/journals-and-publications) and continued training opportunities (http://www.gastro.org/education).

One further point regarding scheduling is that one must be willing and able to see patients urgently, rather than sending them to the emergency room. ERs are appropriate for true emergencies, but are not an ideal place for care when an IBD patient has a flare and requires prompt follow-up. I try to avoid ER visits for my patients unless they are vomiting, have severe abdominal pain, significant bleeding or have clear signs of toxicity. In an ER, abdominal pain equals a CT scan; one should consider seeing these patients in the office and triaging accordingly.

With the increasing requirements of managed care and restrictive medical plans, there has been a similar rise in the frequency of diagnostic test as well as procedure and medication denials. Re-approval and recertification of biologics and other medications have become common, which can add a great deal to your workload and that of your staff. Integration of endoscopy, pathology, and imaging (e.g., ultrasound, CT/CTE) improves response time, dialogue, and can have a positive impact on care. Office infusion allows for a better integration of this service into your practice. There is typically better communication with the infusion nurse(s) and better expedited care as well as fewer cancellations for minor infections. This all helps avoid infusion procedure delays. Infliximab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and lyophilized certolizumab pegol as well as intravenous iron administration can also expand services and enhance quality.

Having a medical assistant, nurse, and others in your practice to assist with patient services and care is a must. There will be many phone calls, emails, and other interactions regarding appointments, consults, routine lab testing, radiology testing, standard medications, biologics, and other treatments that necessitate an effective team-approach. For this role, either a nurse or an experienced medical assistant would be well-suited. Additional support staff and services can also aid our IBD patients. A dietitian knowledgeable in IBD and practical dietary options can, in many instances, prove invaluable. Understanding and utilizing pharma-sponsored “Patient Assistance Programs” provides drug access for the 10-20% (or more) of patients who do not have insurance or biologic coverage. Having specialty access and collegiality with colorectal surgeons, general surgeons, OB/GYNs, dermatologists, hematologists, oncologists, and others is important to expedite consults and provide collaborative care. Finally, offering clinical research options improves access for patients with limited and no coverage and also helps provide needed options for all IBD patients.

This brief overview has hopefully given you some insight into how to provide a higher level of evaluation and care for our IBD patients. These approaches have allowed me to build and maintain a successful IBD practice, and I hope that the integration of some or all of these strategies help you to build and sustain a successful IBD practice.

Dr. Wolf is director of IBD research, Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates.

Anyone can build a successful inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) practice. To do so requires commitment and focus in the area of IBD including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. It also requires a fundamental knowledge of medicine as well as a desire to excel and learn all that one can in these areas. Given the high number of stakeholders, good interpersonal skills are vital. Establishing an IBD practice provides an opportunity to make a big difference in peoples’ lives and the age range of impact is about the broadest in all of medical practice. The more resources you have, the greater the potential impact of your care. Table 1 lists resources that are useful to provide optimal IBD patient care.

You, the gastroenterologist, is the most important resource for the patient. Medical school, residency, fellowship, and “postgraduate” training serves as the foundation for your wealth of knowledge. Maximizing your training is of value, and this can be done by being part of an academic program, keeping abreast of current literature, and attending meetings and post-graduate courses. AGA offers a variety of publications (http://www.gastro.org/journals-and-publications) and continued training opportunities (http://www.gastro.org/education).

One further point regarding scheduling is that one must be willing and able to see patients urgently, rather than sending them to the emergency room. ERs are appropriate for true emergencies, but are not an ideal place for care when an IBD patient has a flare and requires prompt follow-up. I try to avoid ER visits for my patients unless they are vomiting, have severe abdominal pain, significant bleeding or have clear signs of toxicity. In an ER, abdominal pain equals a CT scan; one should consider seeing these patients in the office and triaging accordingly.

With the increasing requirements of managed care and restrictive medical plans, there has been a similar rise in the frequency of diagnostic test as well as procedure and medication denials. Re-approval and recertification of biologics and other medications have become common, which can add a great deal to your workload and that of your staff. Integration of endoscopy, pathology, and imaging (e.g., ultrasound, CT/CTE) improves response time, dialogue, and can have a positive impact on care. Office infusion allows for a better integration of this service into your practice. There is typically better communication with the infusion nurse(s) and better expedited care as well as fewer cancellations for minor infections. This all helps avoid infusion procedure delays. Infliximab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and lyophilized certolizumab pegol as well as intravenous iron administration can also expand services and enhance quality.

Having a medical assistant, nurse, and others in your practice to assist with patient services and care is a must. There will be many phone calls, emails, and other interactions regarding appointments, consults, routine lab testing, radiology testing, standard medications, biologics, and other treatments that necessitate an effective team-approach. For this role, either a nurse or an experienced medical assistant would be well-suited. Additional support staff and services can also aid our IBD patients. A dietitian knowledgeable in IBD and practical dietary options can, in many instances, prove invaluable. Understanding and utilizing pharma-sponsored “Patient Assistance Programs” provides drug access for the 10-20% (or more) of patients who do not have insurance or biologic coverage. Having specialty access and collegiality with colorectal surgeons, general surgeons, OB/GYNs, dermatologists, hematologists, oncologists, and others is important to expedite consults and provide collaborative care. Finally, offering clinical research options improves access for patients with limited and no coverage and also helps provide needed options for all IBD patients.

This brief overview has hopefully given you some insight into how to provide a higher level of evaluation and care for our IBD patients. These approaches have allowed me to build and maintain a successful IBD practice, and I hope that the integration of some or all of these strategies help you to build and sustain a successful IBD practice.

Dr. Wolf is director of IBD research, Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates.

Anyone can build a successful inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) practice. To do so requires commitment and focus in the area of IBD including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. It also requires a fundamental knowledge of medicine as well as a desire to excel and learn all that one can in these areas. Given the high number of stakeholders, good interpersonal skills are vital. Establishing an IBD practice provides an opportunity to make a big difference in peoples’ lives and the age range of impact is about the broadest in all of medical practice. The more resources you have, the greater the potential impact of your care. Table 1 lists resources that are useful to provide optimal IBD patient care.

You, the gastroenterologist, is the most important resource for the patient. Medical school, residency, fellowship, and “postgraduate” training serves as the foundation for your wealth of knowledge. Maximizing your training is of value, and this can be done by being part of an academic program, keeping abreast of current literature, and attending meetings and post-graduate courses. AGA offers a variety of publications (http://www.gastro.org/journals-and-publications) and continued training opportunities (http://www.gastro.org/education).

One further point regarding scheduling is that one must be willing and able to see patients urgently, rather than sending them to the emergency room. ERs are appropriate for true emergencies, but are not an ideal place for care when an IBD patient has a flare and requires prompt follow-up. I try to avoid ER visits for my patients unless they are vomiting, have severe abdominal pain, significant bleeding or have clear signs of toxicity. In an ER, abdominal pain equals a CT scan; one should consider seeing these patients in the office and triaging accordingly.

With the increasing requirements of managed care and restrictive medical plans, there has been a similar rise in the frequency of diagnostic test as well as procedure and medication denials. Re-approval and recertification of biologics and other medications have become common, which can add a great deal to your workload and that of your staff. Integration of endoscopy, pathology, and imaging (e.g., ultrasound, CT/CTE) improves response time, dialogue, and can have a positive impact on care. Office infusion allows for a better integration of this service into your practice. There is typically better communication with the infusion nurse(s) and better expedited care as well as fewer cancellations for minor infections. This all helps avoid infusion procedure delays. Infliximab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and lyophilized certolizumab pegol as well as intravenous iron administration can also expand services and enhance quality.

Having a medical assistant, nurse, and others in your practice to assist with patient services and care is a must. There will be many phone calls, emails, and other interactions regarding appointments, consults, routine lab testing, radiology testing, standard medications, biologics, and other treatments that necessitate an effective team-approach. For this role, either a nurse or an experienced medical assistant would be well-suited. Additional support staff and services can also aid our IBD patients. A dietitian knowledgeable in IBD and practical dietary options can, in many instances, prove invaluable. Understanding and utilizing pharma-sponsored “Patient Assistance Programs” provides drug access for the 10-20% (or more) of patients who do not have insurance or biologic coverage. Having specialty access and collegiality with colorectal surgeons, general surgeons, OB/GYNs, dermatologists, hematologists, oncologists, and others is important to expedite consults and provide collaborative care. Finally, offering clinical research options improves access for patients with limited and no coverage and also helps provide needed options for all IBD patients.

This brief overview has hopefully given you some insight into how to provide a higher level of evaluation and care for our IBD patients. These approaches have allowed me to build and maintain a successful IBD practice, and I hope that the integration of some or all of these strategies help you to build and sustain a successful IBD practice.

Dr. Wolf is director of IBD research, Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates.

Health Maintenance and Preventive Care in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of two chronic inflammatory diseases, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as a small category of patients (~10%) who have atypical features called IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) or indeterminate colitis. The prevalence of IBD ranges from 0.3% to 0.5% overall in North America and Europe.1 In North America, the incidences of CD and UC are estimated to be 3.1 to 14.6 per 100,000 person-years and 2.2 to 14.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively; similar rates are seen in Europe.2 However, incidences up to 19.2 and 20.2 per 100,000 for UC and CD, respectively, have been reported in Canada.3,4 The incidences of both UC and CD are increasing over time in Western countries and in rapidly industrializing countries throughout Asia and South America.5-8

Influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine

Influenza A and B outbreaks are commonly seen during the fall and early spring and risk factors for pneumonia and hospitalization include older age, chronic medical conditions, and immunosuppression. The CDC now recommend annual influenza vaccination for all individuals older than six months. For patients on immunosuppression, the vaccine administered should be the inactivated vaccine, as live attenuated vaccines should not be administered to these patients.

In IBD patients, the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are both well tolerated without an increased rate of adverse effects over the general population and without an increased risk of IBD flares after vaccination.12 A common question for patients on biologic therapy is whether the vaccine should be timed at a specific point in the dose cycle. For infliximab, and likely other biologics, the timing does not change the vaccine immunogenicity and patients should be given these vaccines regardless of where they are in the cycle of administration of their biologic.13 In addition, there is significant response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients on combination therapy with immunomodulators and anti-TNFs and concerns about a lack of response to vaccines should not discourage vaccination since benefits are still acquired by patients even if immunogenicity is somewhat decreased.14,15

Other vaccinations

In addition to the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, adult and pediatric patients with IBD should follow the ACIP recommendations for tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Tdap), Td boosters, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus (HPV), and meningococcal vaccinations.16,17

Live vaccines including measles mumps rubella (MMR), varicella, and zoster vaccines are in general contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients on corticosteroids, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, anti-TNF, and anti-integrin biologics. An inactive varicella-zoster vaccine will likely be available in the near future and may obviate the need for the live vaccine, which is an important development given the increased risk of zoster in patients with IBD on immunosuppression.18

Osteoporosis screening

Skin cancer screening

Multiple studies have demonstrated that immunosuppression, especially with methotrexate and azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (6MP) is a risk factor for the development of initial and recurrent non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in IBD patients, the data for biologics are less definitive.23-25 In addition, biologics are associated with increased risk of melanoma in IBD.26 The elevated risk of skin cancer begins in the first year of treatment with thiopurines and may continue after discontinuation. On the basis of this data, screening for melanoma and NMSC is recommended in IBD patients on immunosuppression. Especially for patients on thiopurines it is reasonable for the initial dermatologist visit to occur in the first year of treatment and thereafter with at least annual visits for a full body skin examination. In addition, it is reasonable to recommend regular sunscreen use and protective clothing such as hats.

Cervical cancer screening

A recent meta-analysis shows that women with IBD on immunosuppression have an increased risk of cervical high grade dysplasia and cervical cancer.27 HPV is the major risk factor for cervical cancer and is necessary for its development. The current American College of Gynecology guidelines for women on immunosuppression are to start cervical cancer screening at 21 and annual screening thereafter with Pap and HPV testing.28

Smoking

Smoking has well known associations with poor outcomes in the general population such as increased risk of lung and pancreatic cancers, as well as high risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, smoking has risks specific to IBD. In CD, smoking is associated with increased disease activity, increased risk of post-operative recurrence, and increased severity of disease.29 Smoking cessation is associated with improved long-term disease outcomes and less risk.30 Making it a point to regularly discuss smoking cessation and partnering with PCPs to offer evidence-based quitting aids may be one of our most significant and beneficial interventions.

Depression and anxiety

Several studies have shown high levels of depression and anxiety in IBD patients and higher levels of depression are associated with increased symptoms, clinical recurrence, poor quality of life and decreased social support.31-33 A recent systematic review of several studies suggested that antidepressants use in IBD patients benefits their mental health and may improve their clinical course as well.34 As such, screening for depression and anxiety regularly and either offering treatment or referral to psychiatrists and psychologists for further management is recommended.10

Conclusion

Patients with IBD frequently develop long-term relationships with their gastroenterologists due to their lifelong chronic disease. It is therefore incumbent on us to be attentive to issues related to IBD patients’ preventive care and collaborate with PCPs to coordinate care for our patients since many of these interventions have both short-term and long-term benefits.

Dr. Chachu is assistant professor and gastroenterologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

References

1. Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-21.e2.

2. Loftus EV, Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1504-17.

3. Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: A Population-Based Study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101(7):1559-68.

4. Lowe AM, Roy PO, M BP, et al. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease in Quebec, Canada. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009;15(3):429-35.

5. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5(12):1424-9.

6. Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, et al. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2013;58(2):519-25.

7. Ng SC, Kaplan G, Banerjee R, et al. 78 Incidence and Phenotype of Inflammatory Bowel Disease From 13 Countries in Asia-Pacific: Results From the Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiologic Study 2011-2013. Gastroenterology.150(4):S21.

8. Parente JML, Coy CSR, Campelo V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2015;21(4):1197-206.

9. Selby L, Kane S, Wilson J, et al. Receipt of preventive health services by IBD patients is significantly lower than by primary care patients. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14(2):253-8.

10. Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017;112(2):241-58.

11. Long MD, Martin C, Sandler RS, et al. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(2):240-8.

12. Rahier JF, Papay P, Salleron J, et al. H1N1 vaccines in a large observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunomodulators and biological therapy. Gut. 2011;60(4):456-62.

13. deBruyn J, Fonseca K, Ghosh S, et al. Immunogenicity of Influenza Vaccine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Maintenance Infliximab Therapy: A Randomized Trial. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(3):638-47.

14. Brezinschek HP, Hofstaetter T, Leeb BF, et al. Immunization of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with antitumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and methotrexate. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2008;20(3):295-9.

15. Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):272-9.

16. Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):136-8.

17. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):134-5.

18. Cullen G, Baden RP, Cheifetz AS. Varicella zoster virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18(12):2392-403.

19. Card T, West J, Hubbard R, et al. Hip fractures in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their relationship to corticosteroid use: a population based cohort study. Gut. 2004;53(2):251-5.

20. Casals-Seoane F, Chaparro M, Mate J, et al. Clinical Course of Bone Metabolism Disorders in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(8):1929-36.

21. Melek J, Sakuraba A. Efficacy and safety of medical therapy for low bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014;12(1):32-44.e5.

22. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2014;25(10):2359-81.

23. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1621-28.e1-5.

24. Long MD, Herfarth HH, Pipkin CA, et al. Increased risk for non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010;8(3):268-74.

25. Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Associated With the Use of Immunosuppressant and Biologic Agents in Patients With a History of Autoimmune Disease and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(2):164-72.

26. Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, et al. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):390-9.e1.

27. Allegretti JR, Barnes EL, Cameron A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease on chronic immunosuppressive therapy at increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia/cancer? A meta-analysis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015;21(5):1089-97.

28. Practice Bulletin No. 168: Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(4):e111-30.

29. Ryan WR, Allan RN, Yamamoto T, et al. Crohn’s disease patients who quit smoking have a reduced risk of reoperation for recurrence. American journal of surgery. 2004;187(2):219-25.

30. Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, et al. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn’s disease: an intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(5):1093-9.

31. Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006;12(8):697-707.

32. Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. General hospital psychiatry. 1996;18(4):220-9.

33. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel J-B, et al. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Are Independently Associated With Clinical Recurrence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.14(6):829-35.e1.

34. Macer BJD, Prady SL, Mikocka-Walus A. Antidepressants in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017;23(4):534-50.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of two chronic inflammatory diseases, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as a small category of patients (~10%) who have atypical features called IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) or indeterminate colitis. The prevalence of IBD ranges from 0.3% to 0.5% overall in North America and Europe.1 In North America, the incidences of CD and UC are estimated to be 3.1 to 14.6 per 100,000 person-years and 2.2 to 14.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively; similar rates are seen in Europe.2 However, incidences up to 19.2 and 20.2 per 100,000 for UC and CD, respectively, have been reported in Canada.3,4 The incidences of both UC and CD are increasing over time in Western countries and in rapidly industrializing countries throughout Asia and South America.5-8

Influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine

Influenza A and B outbreaks are commonly seen during the fall and early spring and risk factors for pneumonia and hospitalization include older age, chronic medical conditions, and immunosuppression. The CDC now recommend annual influenza vaccination for all individuals older than six months. For patients on immunosuppression, the vaccine administered should be the inactivated vaccine, as live attenuated vaccines should not be administered to these patients.

In IBD patients, the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are both well tolerated without an increased rate of adverse effects over the general population and without an increased risk of IBD flares after vaccination.12 A common question for patients on biologic therapy is whether the vaccine should be timed at a specific point in the dose cycle. For infliximab, and likely other biologics, the timing does not change the vaccine immunogenicity and patients should be given these vaccines regardless of where they are in the cycle of administration of their biologic.13 In addition, there is significant response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients on combination therapy with immunomodulators and anti-TNFs and concerns about a lack of response to vaccines should not discourage vaccination since benefits are still acquired by patients even if immunogenicity is somewhat decreased.14,15

Other vaccinations

In addition to the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, adult and pediatric patients with IBD should follow the ACIP recommendations for tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Tdap), Td boosters, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus (HPV), and meningococcal vaccinations.16,17

Live vaccines including measles mumps rubella (MMR), varicella, and zoster vaccines are in general contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients on corticosteroids, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, anti-TNF, and anti-integrin biologics. An inactive varicella-zoster vaccine will likely be available in the near future and may obviate the need for the live vaccine, which is an important development given the increased risk of zoster in patients with IBD on immunosuppression.18

Osteoporosis screening

Skin cancer screening

Multiple studies have demonstrated that immunosuppression, especially with methotrexate and azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (6MP) is a risk factor for the development of initial and recurrent non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in IBD patients, the data for biologics are less definitive.23-25 In addition, biologics are associated with increased risk of melanoma in IBD.26 The elevated risk of skin cancer begins in the first year of treatment with thiopurines and may continue after discontinuation. On the basis of this data, screening for melanoma and NMSC is recommended in IBD patients on immunosuppression. Especially for patients on thiopurines it is reasonable for the initial dermatologist visit to occur in the first year of treatment and thereafter with at least annual visits for a full body skin examination. In addition, it is reasonable to recommend regular sunscreen use and protective clothing such as hats.

Cervical cancer screening

A recent meta-analysis shows that women with IBD on immunosuppression have an increased risk of cervical high grade dysplasia and cervical cancer.27 HPV is the major risk factor for cervical cancer and is necessary for its development. The current American College of Gynecology guidelines for women on immunosuppression are to start cervical cancer screening at 21 and annual screening thereafter with Pap and HPV testing.28

Smoking

Smoking has well known associations with poor outcomes in the general population such as increased risk of lung and pancreatic cancers, as well as high risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, smoking has risks specific to IBD. In CD, smoking is associated with increased disease activity, increased risk of post-operative recurrence, and increased severity of disease.29 Smoking cessation is associated with improved long-term disease outcomes and less risk.30 Making it a point to regularly discuss smoking cessation and partnering with PCPs to offer evidence-based quitting aids may be one of our most significant and beneficial interventions.

Depression and anxiety

Several studies have shown high levels of depression and anxiety in IBD patients and higher levels of depression are associated with increased symptoms, clinical recurrence, poor quality of life and decreased social support.31-33 A recent systematic review of several studies suggested that antidepressants use in IBD patients benefits their mental health and may improve their clinical course as well.34 As such, screening for depression and anxiety regularly and either offering treatment or referral to psychiatrists and psychologists for further management is recommended.10

Conclusion

Patients with IBD frequently develop long-term relationships with their gastroenterologists due to their lifelong chronic disease. It is therefore incumbent on us to be attentive to issues related to IBD patients’ preventive care and collaborate with PCPs to coordinate care for our patients since many of these interventions have both short-term and long-term benefits.

Dr. Chachu is assistant professor and gastroenterologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

References

1. Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-21.e2.

2. Loftus EV, Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1504-17.

3. Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: A Population-Based Study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101(7):1559-68.

4. Lowe AM, Roy PO, M BP, et al. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease in Quebec, Canada. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009;15(3):429-35.

5. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5(12):1424-9.

6. Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, et al. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2013;58(2):519-25.

7. Ng SC, Kaplan G, Banerjee R, et al. 78 Incidence and Phenotype of Inflammatory Bowel Disease From 13 Countries in Asia-Pacific: Results From the Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiologic Study 2011-2013. Gastroenterology.150(4):S21.

8. Parente JML, Coy CSR, Campelo V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2015;21(4):1197-206.

9. Selby L, Kane S, Wilson J, et al. Receipt of preventive health services by IBD patients is significantly lower than by primary care patients. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14(2):253-8.

10. Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017;112(2):241-58.

11. Long MD, Martin C, Sandler RS, et al. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(2):240-8.

12. Rahier JF, Papay P, Salleron J, et al. H1N1 vaccines in a large observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunomodulators and biological therapy. Gut. 2011;60(4):456-62.

13. deBruyn J, Fonseca K, Ghosh S, et al. Immunogenicity of Influenza Vaccine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Maintenance Infliximab Therapy: A Randomized Trial. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(3):638-47.

14. Brezinschek HP, Hofstaetter T, Leeb BF, et al. Immunization of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with antitumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and methotrexate. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2008;20(3):295-9.

15. Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):272-9.

16. Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):136-8.

17. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):134-5.

18. Cullen G, Baden RP, Cheifetz AS. Varicella zoster virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18(12):2392-403.

19. Card T, West J, Hubbard R, et al. Hip fractures in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their relationship to corticosteroid use: a population based cohort study. Gut. 2004;53(2):251-5.

20. Casals-Seoane F, Chaparro M, Mate J, et al. Clinical Course of Bone Metabolism Disorders in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(8):1929-36.

21. Melek J, Sakuraba A. Efficacy and safety of medical therapy for low bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014;12(1):32-44.e5.

22. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2014;25(10):2359-81.

23. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1621-28.e1-5.

24. Long MD, Herfarth HH, Pipkin CA, et al. Increased risk for non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010;8(3):268-74.

25. Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Associated With the Use of Immunosuppressant and Biologic Agents in Patients With a History of Autoimmune Disease and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(2):164-72.

26. Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, et al. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):390-9.e1.

27. Allegretti JR, Barnes EL, Cameron A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease on chronic immunosuppressive therapy at increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia/cancer? A meta-analysis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015;21(5):1089-97.

28. Practice Bulletin No. 168: Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(4):e111-30.

29. Ryan WR, Allan RN, Yamamoto T, et al. Crohn’s disease patients who quit smoking have a reduced risk of reoperation for recurrence. American journal of surgery. 2004;187(2):219-25.

30. Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, et al. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn’s disease: an intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(5):1093-9.

31. Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006;12(8):697-707.

32. Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. General hospital psychiatry. 1996;18(4):220-9.

33. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel J-B, et al. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Are Independently Associated With Clinical Recurrence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.14(6):829-35.e1.

34. Macer BJD, Prady SL, Mikocka-Walus A. Antidepressants in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017;23(4):534-50.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of two chronic inflammatory diseases, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as a small category of patients (~10%) who have atypical features called IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) or indeterminate colitis. The prevalence of IBD ranges from 0.3% to 0.5% overall in North America and Europe.1 In North America, the incidences of CD and UC are estimated to be 3.1 to 14.6 per 100,000 person-years and 2.2 to 14.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively; similar rates are seen in Europe.2 However, incidences up to 19.2 and 20.2 per 100,000 for UC and CD, respectively, have been reported in Canada.3,4 The incidences of both UC and CD are increasing over time in Western countries and in rapidly industrializing countries throughout Asia and South America.5-8

Influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine

Influenza A and B outbreaks are commonly seen during the fall and early spring and risk factors for pneumonia and hospitalization include older age, chronic medical conditions, and immunosuppression. The CDC now recommend annual influenza vaccination for all individuals older than six months. For patients on immunosuppression, the vaccine administered should be the inactivated vaccine, as live attenuated vaccines should not be administered to these patients.

In IBD patients, the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are both well tolerated without an increased rate of adverse effects over the general population and without an increased risk of IBD flares after vaccination.12 A common question for patients on biologic therapy is whether the vaccine should be timed at a specific point in the dose cycle. For infliximab, and likely other biologics, the timing does not change the vaccine immunogenicity and patients should be given these vaccines regardless of where they are in the cycle of administration of their biologic.13 In addition, there is significant response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients on combination therapy with immunomodulators and anti-TNFs and concerns about a lack of response to vaccines should not discourage vaccination since benefits are still acquired by patients even if immunogenicity is somewhat decreased.14,15

Other vaccinations

In addition to the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, adult and pediatric patients with IBD should follow the ACIP recommendations for tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Tdap), Td boosters, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus (HPV), and meningococcal vaccinations.16,17

Live vaccines including measles mumps rubella (MMR), varicella, and zoster vaccines are in general contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients on corticosteroids, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, anti-TNF, and anti-integrin biologics. An inactive varicella-zoster vaccine will likely be available in the near future and may obviate the need for the live vaccine, which is an important development given the increased risk of zoster in patients with IBD on immunosuppression.18

Osteoporosis screening

Skin cancer screening

Multiple studies have demonstrated that immunosuppression, especially with methotrexate and azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (6MP) is a risk factor for the development of initial and recurrent non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in IBD patients, the data for biologics are less definitive.23-25 In addition, biologics are associated with increased risk of melanoma in IBD.26 The elevated risk of skin cancer begins in the first year of treatment with thiopurines and may continue after discontinuation. On the basis of this data, screening for melanoma and NMSC is recommended in IBD patients on immunosuppression. Especially for patients on thiopurines it is reasonable for the initial dermatologist visit to occur in the first year of treatment and thereafter with at least annual visits for a full body skin examination. In addition, it is reasonable to recommend regular sunscreen use and protective clothing such as hats.

Cervical cancer screening

A recent meta-analysis shows that women with IBD on immunosuppression have an increased risk of cervical high grade dysplasia and cervical cancer.27 HPV is the major risk factor for cervical cancer and is necessary for its development. The current American College of Gynecology guidelines for women on immunosuppression are to start cervical cancer screening at 21 and annual screening thereafter with Pap and HPV testing.28

Smoking

Smoking has well known associations with poor outcomes in the general population such as increased risk of lung and pancreatic cancers, as well as high risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, smoking has risks specific to IBD. In CD, smoking is associated with increased disease activity, increased risk of post-operative recurrence, and increased severity of disease.29 Smoking cessation is associated with improved long-term disease outcomes and less risk.30 Making it a point to regularly discuss smoking cessation and partnering with PCPs to offer evidence-based quitting aids may be one of our most significant and beneficial interventions.

Depression and anxiety

Several studies have shown high levels of depression and anxiety in IBD patients and higher levels of depression are associated with increased symptoms, clinical recurrence, poor quality of life and decreased social support.31-33 A recent systematic review of several studies suggested that antidepressants use in IBD patients benefits their mental health and may improve their clinical course as well.34 As such, screening for depression and anxiety regularly and either offering treatment or referral to psychiatrists and psychologists for further management is recommended.10

Conclusion

Patients with IBD frequently develop long-term relationships with their gastroenterologists due to their lifelong chronic disease. It is therefore incumbent on us to be attentive to issues related to IBD patients’ preventive care and collaborate with PCPs to coordinate care for our patients since many of these interventions have both short-term and long-term benefits.

Dr. Chachu is assistant professor and gastroenterologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

References

1. Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313-21.e2.

2. Loftus EV, Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1504-17.

3. Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: A Population-Based Study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101(7):1559-68.

4. Lowe AM, Roy PO, M BP, et al. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease in Quebec, Canada. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009;15(3):429-35.

5. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5(12):1424-9.

6. Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, et al. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2013;58(2):519-25.

7. Ng SC, Kaplan G, Banerjee R, et al. 78 Incidence and Phenotype of Inflammatory Bowel Disease From 13 Countries in Asia-Pacific: Results From the Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiologic Study 2011-2013. Gastroenterology.150(4):S21.

8. Parente JML, Coy CSR, Campelo V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2015;21(4):1197-206.

9. Selby L, Kane S, Wilson J, et al. Receipt of preventive health services by IBD patients is significantly lower than by primary care patients. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14(2):253-8.

10. Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017;112(2):241-58.

11. Long MD, Martin C, Sandler RS, et al. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(2):240-8.

12. Rahier JF, Papay P, Salleron J, et al. H1N1 vaccines in a large observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunomodulators and biological therapy. Gut. 2011;60(4):456-62.

13. deBruyn J, Fonseca K, Ghosh S, et al. Immunogenicity of Influenza Vaccine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Maintenance Infliximab Therapy: A Randomized Trial. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(3):638-47.

14. Brezinschek HP, Hofstaetter T, Leeb BF, et al. Immunization of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with antitumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and methotrexate. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2008;20(3):295-9.

15. Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):272-9.

16. Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):136-8.

17. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(5):134-5.

18. Cullen G, Baden RP, Cheifetz AS. Varicella zoster virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18(12):2392-403.

19. Card T, West J, Hubbard R, et al. Hip fractures in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their relationship to corticosteroid use: a population based cohort study. Gut. 2004;53(2):251-5.

20. Casals-Seoane F, Chaparro M, Mate J, et al. Clinical Course of Bone Metabolism Disorders in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(8):1929-36.

21. Melek J, Sakuraba A. Efficacy and safety of medical therapy for low bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014;12(1):32-44.e5.

22. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2014;25(10):2359-81.

23. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1621-28.e1-5.

24. Long MD, Herfarth HH, Pipkin CA, et al. Increased risk for non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010;8(3):268-74.

25. Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Associated With the Use of Immunosuppressant and Biologic Agents in Patients With a History of Autoimmune Disease and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(2):164-72.

26. Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, et al. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):390-9.e1.

27. Allegretti JR, Barnes EL, Cameron A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease on chronic immunosuppressive therapy at increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia/cancer? A meta-analysis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015;21(5):1089-97.

28. Practice Bulletin No. 168: Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(4):e111-30.

29. Ryan WR, Allan RN, Yamamoto T, et al. Crohn’s disease patients who quit smoking have a reduced risk of reoperation for recurrence. American journal of surgery. 2004;187(2):219-25.

30. Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, et al. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn’s disease: an intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(5):1093-9.

31. Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006;12(8):697-707.

32. Walker EA, Gelfand MD, Gelfand AN, et al. The relationship of current psychiatric disorder to functional disability and distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. General hospital psychiatry. 1996;18(4):220-9.

33. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel J-B, et al. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Are Independently Associated With Clinical Recurrence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.14(6):829-35.e1.

34. Macer BJD, Prady SL, Mikocka-Walus A. Antidepressants in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017;23(4):534-50.

The 'Nuts and Bolts' of Drug Concentration Monitoring in IBD

Introduction

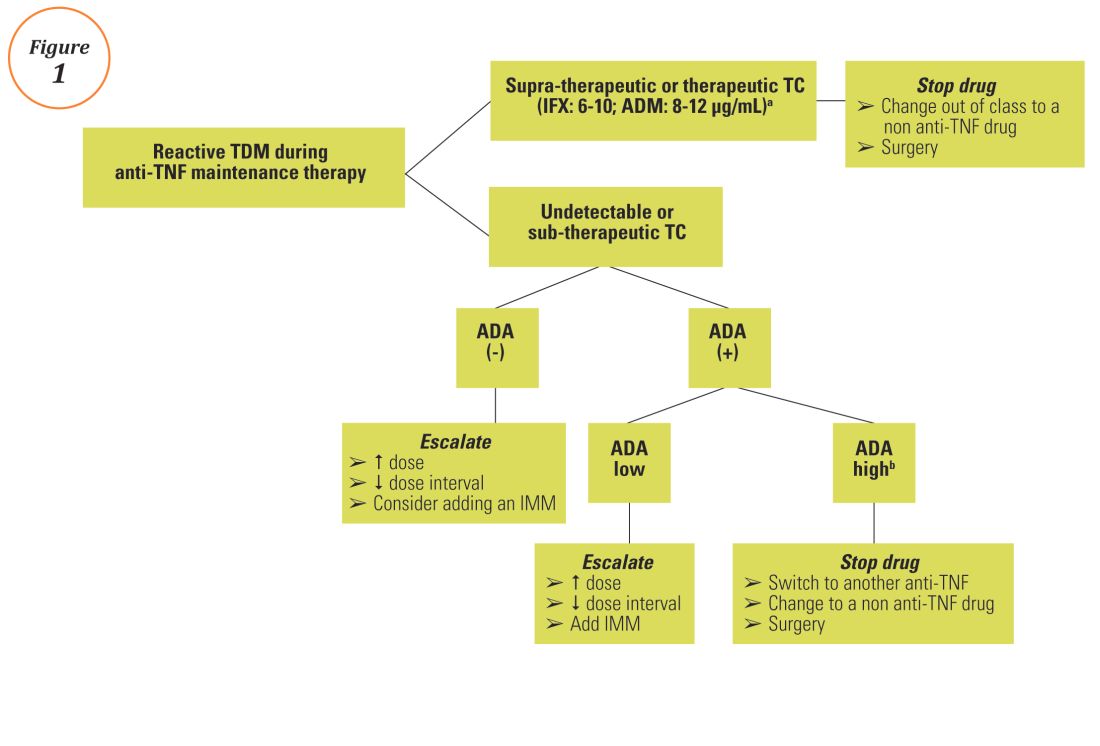

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy is the cornerstone of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment.1 Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients show no clinical benefit, considered as primary non-responders, while another 50% lose response over time and need to escalate or discontinue anti-TNF therapy due to either pharmacokinetic (PK) or pharmacodynamic issues.2 Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), defined as the assessment of drug concentration and anti-drug antibodies (ADA), is emerging as a new therapeutic strategy to better explain, manage, and hopefully prevent these undesired clinical outcomes.3 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that higher serum anti-TNF drug concentrations both during maintenance and induction therapy are associated with favorable objective therapeutic outcomes, suggesting of a ‘treat-to-trough’ in addition to a ‘treat-to-target’ therapeutic approach.4-6 This concept of TDM is not new in IBD. TDM has also been used for optimizing thiopurines.7 This brief review will discuss a practical approach to the use of TDM in IBD with a focus on its use with anti-TNF therapies.

Reactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy